| Articles - Opiates, heroin & methadone |

Drug Abuse

Substitution treatment with- methadone in Germany: politics, programmes and results

Uwe Verthein *, Jens Kalke, Peter Raschke

University of Hamburg, Germany

Abstract

In Germany, methadone treatment for opiate addicts has been approved only during the last 1ew years. The development of' methadone treatment took place under special political conditions. The federal system in Germany made it possible to establish methadone treatment in some states against the opposition of the German government. The result was the development of different forms of methadone therapy with different indications and treatment rules. With respect to somatic and mental health, social integration and consumption patterns, the results of German evaluation studies show an overall quite similar effect of methadone treatment programmes. The relations between the regulations of' different types of programmes and treatment effects are discussed.

1. Introduction

In the following, we like to present an overview of the German methadone therapies' policies. 11 is about the development of the drug policy, which still is behind other more progressive countries, about the wide range of German methadone programmes and about the successes of therapies.

The drug policy of the German government has been and still is dominated by outdated approaches. By that we mean discrimination, deterrence as a mean of prevention, abstinence as the main way of helping as well as a continued and ever brutally fought 'war on drugs'. A drug free society, only free of' assorted drugs, is still the leading role model.

In recent years the conservative government has been blockading all major reform bills on drug policies such as new forms of therapies, an effective decriminalization of drug use or harm-reduction policies. Some reforms actually being implemented were watered down and adapted at a very late point of time (Kalke and Raschke, 1996). Even the Constitutional Court, which is the highest court in Germany, has a much more subtle and differentiated stance on the question of so-called soft and hard drugs than the government's stereotypes. The court's ruling on the use of cannabis in March 1994 is a case in point here (Bundesverfassungsgericht des Bundesrepublik Deutschland 1994).

Changes of the German drug policy have mostly been initiated by the big cities which are on the front line of' the problem. The German federal states of Hamburg and Hessen triggered several nation-wide debates by being the first to start a number of reforms (Bossong, 1994). When it comes to illegal drugs, Germany has a cleavage line of conflict here between left-wing liberals, that is, in the German case, the Social Democratic and the Green Party and right-wing conservatives, being the ruling coalition. The Social Democrats and the Greens are in favor of reforms, whereas the government insists on a drug policy based on abstinence and repression. The development of methadone treatment programmes also shows this left-right conflict in Germany's drug policy.

2. Political development

Methadone treatment is a comparatively new form of therapy for drug addicts. There was only one model experiment in Hannover in the early 1970s (Krach and Peschke, 1987). Other than that and in contrast to many other Western countries, methadone was strictly rejected in Germany. There used to be a 'syndicate of abstinence' consisting of politicians, physicians and drug relief' workers. They propagated a theory of suffering. This theory had it, that in-patient long-term therapies were the best mankind ever came up with in drug therapies. They believed in the dogma of abstinence. which had to precede any treatment and social reintegration of drug addicts. Methadone treatment managed to revolve this unbearable theory.

It was not until the increasing problems in the wake of the spread of HIV and the rising number of people dying because of drug consumption that the clear deficits of the traditional policy were taken under reconsideration. Only then, we are now in the mid 1980s, discussion about methadone therapy started. The state of Nordrhein Westfalen launched the first methadone program in 1988. The state's social democratic government had to fight it through against the conservative federal German government. It was a state-run program accompanied by scientific research. Given the broad front of criticism and uncertain legal position, methadone therapy had an extremely difficult start.

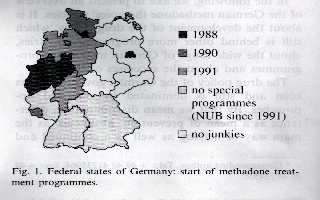

Half a year later the state of Hamburg followed suit. Here a substitution program was worked out that was supported by the Hamburg Board of Physicians. For the first time the health insurance companies in Germany paid for the substance and the medical treatment. Nordrhein-Westfalen and Hamburg had set examples and other states, ruled by Social Democrats (Schleswig-Holstein, Hessen and Saarland) followed (Fig. 1).

There was criticism from the German government. It warned, that methadone treatment, which would not be a therapy would still spill over the whole country. They, therefore, saw the paradigm of abstinence in doubt, The federal government could not stop the projects, however, because the individual states had installed them using their political leeway to the very extent possible. The federal and state laws were not definite on who actually was in charge. What is more, the methadone programmes were based on a big coalition of the states' various actors: the welfare department, the Board of Physicians, health care companies and drug relief organisations, which rendered the states well protected against other external intervention.

Due to public pressure and an increasing number of states' programmes in July 1991, the Standing Committee of Physicians and Health Care passed guidelines (NUB-Richtlinien) for methadone treatment (Bundesausschuf3 ffir Arzte und Krankenkassen, 1991, 1992). Although these NUB-guide-lines were meant to be implemented federally, the states interpreted them individually and integrated them into their already existing programmes. The NUB-guide-lines are restrictive conditions for methadone treatment. They thus meet the government's aim that methadone therapy be the last resort of therapies, if at all. Despite their restrictive nature in the first years. the NUB guide-lines helped methadone substitution to expand in Germany because they laid out a sound judicial base for the first time.

In 1995 the IFT in Munich and a related group of experts (136hringer et a]., 1995) publishedmethadone-standards' which were in some way trying to clarify the indications for treatment in order to give more opiate addicts the chance to get in. On the other hand, the structure and practice of treatment was restricted by new conditions and limitations which did not help to establish methadone treatment as a 'normal' therapy for opiate addicts. Furthermore, regarding the aims of methadone treatment there was no agreement in the group. (Standard No. I is presented twice with different contents.) At the beginning of 1997 the Federal board of Physicians (Bundes5rztekammer 1997) passed guidelines for substitution treatment of opiate addicts in Germany. These guidelines can essentially be seen as one step forward. But the publication of these guidelines will not help to clarify indications and practice of' the treatment because the conditions under which methadone therapy is paid by the health assurances are limited by the NUB-guidelines.

Due to the lack of heroin addicts for a long time, in the eastern federal states (Ex-GDR) they have not yet launched methadone treatment programmes. As one can see in Fig. 1, concerning the extent of methadone treatment, there is a north south decline in Germany.

The federal government very hesitatingly made adjustments to methadone treatment. In summer 1992, the Law on Narcotics and Drugs (BtMG) was clarified. It now says, that in individual cases, which have to be justified on medical grounds, a methadone treatment is legal. It has to take place under strict surveillance by a physician (i.e. GP). This adjustment to the Law on Narcotics also served the government to block oft' any further expansion and liberalization of substitution therapies. Taking into consideration numerous scientific findings, the government, instead of trying to handle methadone treatment in more flexible ways, it rather kept on fighting for a restrictive way of therapy, which was outdated by any scientific and practical standards.

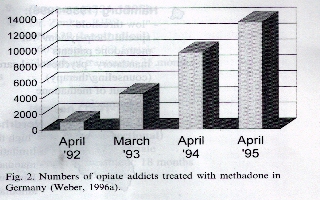

Due to the individual interpretation of the NUB-guide-lines on methadone therapies (I mentioned that above), methadone treatment has been increasing over the past 3 years (Fig. 2). Currently there are about 15 000 opiate addicts in methadone treatment in Germany (Weber, 1996b).

3. Programmes

Due to the differentiating drug politics in the federal states, the individual programmes in the states differ in their structure and their concrete practical approach to substitution treatment, such as the criteria for admission, indication rules, counseling services, the modalities of handing out methadone and the financial modalities.

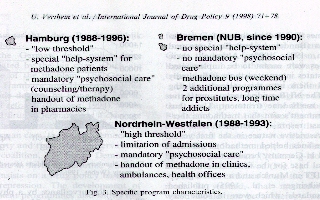

Some states set higher thresholds than others to their programmes, such as extensive entry modalities, strict criteria for indication and a limit to the number of persons per program. This is the case in Nordrhein-Westfalen and Saarland.

Other programmes (e.g. Hamburg, SchleswigHolstein) have lower thresholds but a more structured frame. Here there is a commission on deciding whether or not a person may participate, mandatory counseling (once a week as a rule) and a respective infrastructure (Fig. 3).

Some states installed methadone programmes according to the federal NUB-guide-lines or they integrated these guide-lines into existing programmes. These programmes may still include state-specific points: Berlin, e.g. handles a participant's additional consumption of other drugs less restrictive than the federal NUB-guide-lines demand. On the other hand, it demands a more mandatory participation of counseling services than required in the guide-lines. The city of Bremen added special programmes for certain groups of patients.

Those states, which have always been and at times still are sceptical towards methadone treatment for heroin addicts, strictly work along the federal NUB-guide-lines without any additions or further specifications of the state's responsibility. That is the case in the Southern conservative states of Bavaria and Baden-Wurttemberg.

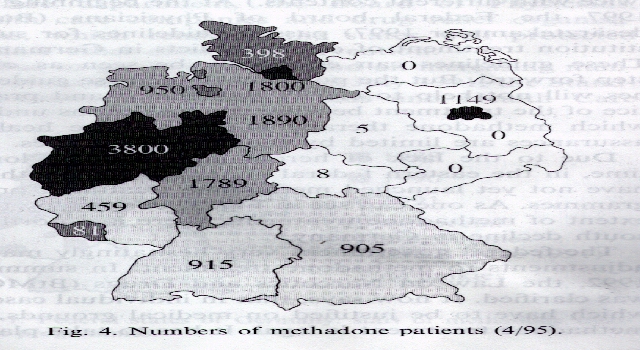

The variety of the programmes is reflected in the varying number of patients. The three big cities of Hamburg, Bremen and Berlin comprise 28% ofall German methadone patients, but only 91V~, of the country, s population. The high number of patients does not only reflect the high proportion of heroin addicts in big cities, but also that these cities at a very early stage got involved with methadone. As explained earlier, they had special programmes prior to the federal NUB-guide-lines. Besides the big cities, the states of Nordrhein -Westfalen, Hessen and Niedersachsen are very active in this field (Fig. 4).

Up to the beginning of 1994 only levomethadone (LPolamidon"') was allowed to be prescribed by the doctors in Germany. (Lcvomethadone is about twice as efficient as methadone.) Since the introduction of the racemic form of methadone there has been a change in the prescription from levomethadone to racemic methadone which is less expensive and should have less side effects (Poehlke 1994; Raschke et al., 1996). But not every doctor changed the medication. Some patients complained about less effects and intolerance, so levomethadone was prescribed again. In Germany there is only one double-blind study comparing the effects of racemic methadone and levomethadone (Schcrbaum et al., 1996). The authors did not find any significant differences between the patients receiving racemic methadone and the levomethadone group.

4. Results

The evaluation studies accompanying methadone therapies are just as new and heterogeneous as the objects they cover. The scientific backlog in methadone treatment equals the deficit of practical experience. Therefore, Germany has got a big backlog demand, despite the fact, that methadone treatment has been more than any other method at the focus of evaluation studies world-wide (e.g. Ball and Ross, 1991; Ward et al., 1992; Verthein et al., 1994).

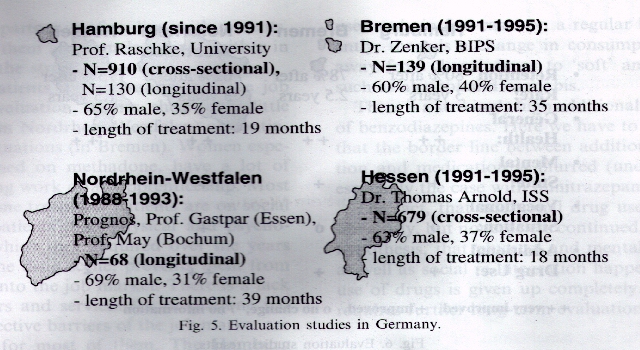

There are four comparatively big follow-up research projects on methadone treatment in Germany, namely in Hamburg, Bremen, NordrheinWestfalen and in Hessen. These projects serve as examples to show the results of the German scientific research on methadone treatment so far (Fig. 5). There are also a number of smaller research projects and clinical studies, but since they come to similar results, we will omit them here.

Accompanying evaluation research is completed except for Hessen. Hamburg and Hessen have more patients participating in surveys than others, so for the moment they are evaluated in cross section only. The results are compared to the situation before treatment. The longitudinal section analyses in Hamburg, Bremen and Nordrhein-Westfalen are based on smaller samples. In the following, the results of the studies are presented as a very general overview. (For more detailed information see: Hamburg: Verthein et al., 1995; Raschke et al., 1996; Bremen: Zenker, 1995; Lang and Zenker, 1994; Nordrhein-Westfalen: Ministerium far Arbeit, Gesundheit und Soziales, 1993; Hessen: Arnoldt et al., 1995).

About one third of the methadone patients are female. The average treatment takes 27 months in Hamburg and about 18 months in Hessen. Patients from Nordrhein-Westfalen and Bremen, who were asked several times, had been in therapy for about 3 years.

4. 1. Retention rate

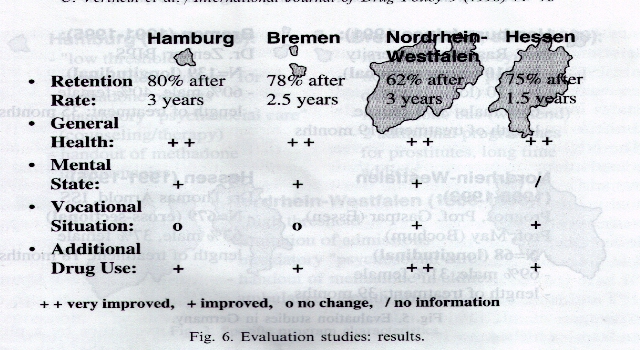

All methadone programmes show high retention rates. Hamburg and Bremen may serve as cases in point here. Although the criteria of indication and the mandatory conditions of the therapy have been eased over the last 2 years, 80'Yo of the patients were still in substitution therapy after over 2 years and 6 months (Fig. 6).

4.2. Health and psychic well-being

All evaluation studies on methadone treatment unanimously indicate a fast and clear improvement of the patients' general health. This goes for nutrition, the patients' weight approaches their normal weight in the course of treatment, as well as for a significant decrease of abscesses and liver diseases.

Side effects, such as transpiration, obstipation and sleeping disturbances caused by methadone do not lead to major impacts on the general well-being. Infections with the HIVvirus after the start of the therapy occurred only rarely. There are 3-5 cases in Hamburg, I in Nordrhein-Westfalen, I in Bremen and 2 cases in Hessen.

The psychic well-being also increased. Most of' the patients showed a positive trend. They developed positive perspectives for their own futures. A majority of them suffered from depressions, angst and other psychic problems before they started methadone treatment. In the course of the therapy these problems decreased. The suicide rate among them also dropped.

However, a few patients' well-being deteriorated or their psychic situation stabilized on a more negative level (1020'Y~,). These patients suffer frequent or regularly from minor depressions during methadone treatment. These depressions can be seen as a reaction to the newly opened 'hole' created by the new freedom not to have to make the money for drugs all the time. They might also be the effect of an improper dosage of methadone or of additional drug use, or they indicate psychiatric diseases, which the patients had prior to methadone treatment and which now surface in this way. That is the so called 'unmasking effect' as a result of substitution treatment.

4.3. Social situation and rehabilitation into work

Methadone therapy has its effect on the social environment of the patients: there is a significant increase in 'drug-free' social contacts and at the same time patients distance themselves from the drug scene. Their relationships with their partners stabilize and they intensify leisure-time activities and sports.

Their living conditions can be described as satisfactory. They either live in their own apartment or with their partner, a few live with parents. About 10% of them are homeless, living either in shelters or on the street.

As to the patients' re-integration into the job market, the evaluation studies show only little improvement (in Nordrhein-Westfalen) or continued desolate situations (in Bremen). Women especially, maintained on methadone, have a lot of problems finding work or an apprenticeship. Most of the methadone treatment patients are on social welfare. The patients' bad physical and psychological state, which they acquired over the years they lived in the drug scene, prevents them from rehabilitation into the job market. There is a lack of' special offers and services for methadone patients. The objective barriers of the job market are unsurpassable for most of them. The Hamburg study found a big correlation between the patients' work situation and their fitness for work. The patients who are judged by the GPs as capable of employment are much better integrated into the job market than those who are incapacitated.

The patients social stabilization is better shown when it comes to their legal behavior and situation. The evaluation studies indicate a tremendous decrease of crimes in order to make the money for drugs. After the therapy started, the patients' arrest and conviction rate dropped markedly. The same can be said about any of their conflicts with the law and the police. Most of the offences occurring with patients maintained on methadone concern the Law on Drugs and Narcotics (BtMG). They are patients with a continued consumption of illegal drugs. Their rate for Hamburg, e.g. is about 11%.

4.4. Additional consumption of drugs

The results so far unanimously show the same line of development of additional drug use: There is a positive change regarding both the choice of drugs as well as the amount being used. Several times additional drug use is given up all together. Most obviously, the use of heroin decreases. However, lots of methadone patients use it occasionally. The additional use of benzodiazepines plays a major rule for quite some time. Cocaine, amphetamines and barbiturates, however, are being used only in few cases on a regular basis. Apparently, there is a change in consumption patterns away from 'hard' drugs to 'soft' and legal ones, such as alcohol and cannabis.

There is a strikingly high additional consumption of benzodiazepines. Here we have to bear in mind that the border line between additional consumption and medication is blurred (unclear). This is especially the case with flunitrazeparn (rohypol).

The fact, that additional drug use is decreased obviously, but nonetheless continued, supports the hypothesis, that physical and mental stabilization as well as social re-integration happens before the use of drugs is given up completely. This finding requires further long-term evaluation studies.

5. Conclusions

The political system in Germany, her division in federal states, made it possible that methadone therapy was established against the federal government. In the disguise of models and experiments, this new drug relief system was established 'from below', e.g. from city level up to state level. This reform policy meets its borders where it touches federal regulations, because here the conservative government blocks any further progress. The 'methadone-standards' by 136hringer et a]. (1995) and the guidelines of the Federal Board of Physicians (Bundesarztekammer 1997) could not contribute to a liberalization and expansion of methadone treatment in Germany. The payment for treatment is still limited by the restrictive NUB-guidelines.

Due to the comparatively short duration of treatment, the results of the German studies must be interpreted with caution. Therefore, from this we can only draw preliminary conclusions. The results obtained so far from the evaluation studies accompanying methadone therapies unanimously show a comparatively quick improvement of the patients' somatic and mental health. Most of the patients clearly distance themselves from the public drug scene and reintegrate socially into a drug-free environment. Their crime rate in order to make money for drugs drops markedly.

On the other hand, re-integration into the job market does not go along with their social re-integration. Also, they do not totally give up the additional consumption of illegal drugs and medication. There are only a few cases during the time that was covered by the evaluation projects, in which a therapy ended successfully in the sense that both the illegal drugs and methadone were given up.

Evaluation studies may occasionally show diverging results regarding, e.g. the job re-integration or the legal probation, the reasons might be both regional differences of the programmes as well as varying samples and methods of the research projects. These differences, however, are not essential. In any case, do all the German results confirm the conclusions of international studies, that methadone treatment is an efficient harm reduction strategy for opiate addicts and thus saves their lives'?

It is worth noting, that despite the wide variety of programmes in Germany, the scientific analyses all reach similar results, a basically positive trend or the patients' health and psychic and social well-being. Altogether, the different kinds of methadone programmes do not lead to different effects of treatment These results rise many questions and demand further longterm (and longitudinal) research. Which elements of the program have which impact on the course and outCome of' methadone treatment'? What role plays intensive psycho-social care, such as counseling or psychotherapy, within the framework of methadone treatment'? Special structural analyses and comparative program evaluation studies are necessary in order to be able to evaluate the different methadone programmes' efficiency.

References

Arnoldt T, Feldincier-Thon J, Frietsch R, Simmedinger R. Wein hillt Methadon? Daten, Fakten, Analysen: Ergebnisse der wissenschaftlichen Begleitung der Substitutions behandlung in Hessen. Frankturt am Main: Institut ffir Sozialarbeit und Sozialpaclagogik, 1995.

Ball JC, Ross A. The Effectiveness of' Methadone Maintenance Treatment. New York: Springer, 1991.

Bossong H. Ways out of an 'as if" policy. International Journal of' Drug Policy 1994~5:62 -9.

Buhringer G, Gastpar M, Heinz W, Kovar K-A, Ladewig D, Naber D, T~ischner K-L, Uclitenliagen A, Wanke K. Methadon-Standards. Vorschl:ige zur Qualulitssicherung bei der Methadon-Substitution im Rahmen der Behandlung von Drogenabh~inginen, Stuttgart: Erike, 1995.

Bunde6rztekarnmer. Leitlinien der Bundesarztekarnmer zur Substitutionstherapie Opiatabhangiger.Dewsches ,4r_-1eb1(m 1997:94: 312 -4,

BundesausschuB ffir ~rztC Lind Krankenkassen. Erweiterungen der NUB Richtlinien. Deutsches Arzteblatt 1991 ~89:21802.

BundesausschuB I'm--- Arzte und Krankenkassen. Andeiungen der NUB Richtlinien. DeLusches Arzteblatt 1992~89:2489 90.

Bundesverl'assungsgericht der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Beschluf3 vom 9. M;irz 1994. Unigang mit Cannabisproduktcn. In: BVerfGF, Band 90~ S:145 99.

Kalke J, Raschke P. Blockiertc Drogenpolitik. Von Reforminitiativen der L'inder und ilirer Behinderung durch die BundesregicrUng. In: Akzept e.V. (firsg.) Wider besseres Wissen. Die Sclieinliciligkeit der Drogenpolitik. 1996:18690.

Krach C. Peschke H. Das Hannovcrschc Methadonprogramm I I Jahre danach. Manuskript. Hannover, 1987.

Lang P, Zenker C. Substitutionsbehandlung Drogenabhingigcr mit Methadon. Fin Zwischenbericht der Begleitf'orschung in Bremen, Sucht 1994A0:253 265.

Ministerium f*6r Arbeit, Gesundheit und Soziales NRW. Abschlubbericht: Wissenschaftliches Erprobungsvorhaben medikamentengest6tzte Rehabilitation bei i.v. K61n: Opiatabliiingigen, 1993.

Poefilke T. Aninerkungen zur Diskussion urn die Urnstellung von LPolarniclon auf Methadon.Wesifidisches 4rztehlatt, 1994,16 18.

Raschke P, Verthein U, Kalke J. Substitution in Hamburg, Methadonbehandlung Opiatabhangiger von 1990 his 1995. Hamburg: Forschungsbericht, 1996.

Scherbaurn N, Finkbeiner T, Leifert K, Gastpar M. The efficacy of' 1niethadone and racernic methadone in substitution treatment for opiate addicts - a double-blind comparison.Pharnwcop.svchiatrv 1996;29:212 5.

Verthein U, Kalke J, Raschke P. Resultate internationaler und bundesdeutscher Evaluation.sstudien zur Substitutionstherapie mit Methadon, cine (Jbcrsicht. Psychotherapic Psychosomatik Medizinische Psychologie 1994A4:128 36.

Verthein U, Raschke P. Kalke J. Methadone therapy in Hamburg. European Addiction Research 1995;1:99-105.

Ward J, Mattick RP, Hall W. Key Issues in Methadone Maintenance Treatment. Kensington: New South Wales University Press, 1992.

Weber 1. M ethadon substitution in der vertrags5rztlichen Versorgung, Ergebmsse einer Stichtagserheburig. Das Gesundheitswesen 1996a;58:20712.

Weber 1. Methadonsubstitution: Geringerer Zuwachs an Patienten. Deutsches Arzteblatt 1996b:93:679.

Zenker C. First results of a methadone programme for drugaddicted women prostituting themselves. European Addiction Research 1995J:139 45.