| Articles - Opiates, heroin & methadone |

Drug Abuse

METHADONE PROVISION IN THE UK

Michael Farrell, Louise Sell, Jan Neeleman, Michael Gossop, Paul Griffiths, Ernst Buning, Emily Finch and John Strang, 'The National Addiction Centre, London, UK; 'Department of Psychological Medicine, King's College School of Medicine and Dentistry; 'Municipal Health Department, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Drug problems have grown substantially in the UK over the past two decades. There has been considerable diversity in response to drug problems with a combination of community based primary care and specialist services. Methadone substitution services have more than tripled and are delivered in a diverse range of settings but the majority of methadone is delivered in non-supervised community pharmacy settings. The use of other opiate agonists such as heroin is carried out with a small minority of clients. The services continue to change and adapt to the changing nature of the drug problem in the community. A brief background history and current organisation of services is provided.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Prior to the 1960s there were negligible problems with illicit drugs in the UK. In 1916, in response to concern from the Police and Service authorities about the abuse of cocaine by servicemen, the special wartime powers provided by the Defence of the Realm Act were used to make it an offence to be in unauthorised possession of cocaine. This law was replaced by the Dangerous Drugs Act in 1920 and a subordinate regulation of 1921, which extended the earlier control to morphine and heroin. These continued to be the framework of control. This legislation also put in place the responsibility of the police to inspect pharmacy records on the dispensing of opiates and cocaine.

Subsequently the Rolleston Committee produced a report confirming the role of doctors in the response to addiction. The situation between the 1920s and 1950s remained quiet and stable and in the early 1960s there was a feeling that all addicts were known to the Home Office and the Ministry of Health. Problems grew in the 1950s when a substantial market in heroin tablets grew in London. A small number of doctors prescribed tablets. A significant black-market grew out of this form of prescribing (Spear, 1994). At that stage, however, the majority of doctors wanted as little contact as possible with addicts. The growth of the market in prescribed heroin and cocaine resulted in the establishment of the Brain Committee (1966). The Committee recommended the restriction of the right of general practitioners to prescribe heroin and cocaine and recommended the establishment of the drug dependence units with specialist doctors to prescribe for addicted patients.

At this stage, the problem remained quite small with between 3000and 5000 heroin addicts using services. The growth of the use of illicit drugs continued through the 1970s but remained relatively stable through the 1970s until the late 1970s when there was a heroin epidemic. Between the late 1970s and the early 1980s there was a large growth in the volume of smokable heroin and injectable heroin in all parts of the UK. This problem continued throughout the 1980s. By the mid to late 1980s there was a sudden growth in the acid house music culture with major media coverage on MDMA (ecstasy) and other hallucinogenic drugs. This separate music and drug culture developed into a major social phenomenon through the late 1980s and early 1990s. Amphetamines were reported as a problem from the 1950s and reported as a significant problem in terms of police seizures in the 1980s; they became a substantial issue in relation to HIV risk-taking behaviour and injecting during the 1980s and 1990s. In particular, in the late 1980s and into the 1990s, cocaine became established as another major drug of abuse in the UK.

In the early 1970s there was a barbiturate epidemic with chaotic drug users being involved in major problematic use with intoxication, overdoses and withdrawals with epileptic fits. These drug users made a major impact on Accident and Emergency services.

DEVELOPMENT OF SERVICES

Prior to 1968 there was no specialist service for drug misusers, but, after the Dangerous Drugs Act, specialist services were established. There were clearly three phases of service development with 10% of services developing before 1970, 19% mainly residential rehabilitation services in the 1970s and the majority of services (7 1 %) established after the central funding initiative in 1984. It has been argued that HIV and AIDS have stimulated the development of the public health model of drug services (Stimson, 1995). The work of Dr Roy Robertson of Edinburgh (Robertson, 1989) initially detected HIV among over 60% of his IVDU patients.

Robertson's work alerted policy makers and service planners to the risk of HIV in the mid to late 1980s. The implications of HIV spread among drug users resulted in a large range of proactive prevention strategies with increased funding for the expansion' of community drug services and the development of a wide network of needle exchange programmes.

DEVELOPMENT OF SUBSTITUTE PRESCRIBING SERVICES

Substitute prescribing was in existence in the UK during the 1920s and 1930s but was not identified as such. Most of those receiving substitute drugs at that stage were addicted doctors and professionals who were self medicating. General practitioners had the right to prescribe any drugs they wished to, hut most refrained from any prescribing. Due to the growth in the illicit trade of prescribed drugs in the 1950sand 1960s, the first specialised substitute prescribing services were established in the late 1960s. The publication of research from the US on the benefits of methadone maintenance occurred simultaneously with the introduction of methadone. In the UK this led to a gradual decline in the amount of heroin prescribed during the 1970s and a substantial increase in the amount of' injectable methadone prescribed up until 1975.There was a gradual reduction in injectable methadone prescribing after that, and a substantial increase in the amount of oral methadone prescribed. This shift from injectable to oral methadone was influenced by a randomised control trial conducted by Hartnoll et al.(1980) in the late 1970sand early 1980s. Essentially this study reported that heroin prescribing resulted in better clinic attendance and some reduction in criminal activity but little other psychosocial change or reduction in physical complications from injecting' drug use. This resulted in a debate on the benefits of injectable prescribing and a gradual move away from injectable prescribing.

It would appear that many of those who had initially been prescribed injectable methadone continued on it through the 1970s and 1980s, but that new entrants into the system were more likely to be offered oral methadone. There was also a significant shift away from long-term prescribing into short-term prescribing of oral methadone in the 1970s and 1980s.

The advent of HIV and AIDS resulted in a resurgence of interest in longer-term prescribing and a gradual growth in the number on long-term substitute prescriptions. Despite the introduction of new services and modification of services in response to changed information, the problem of drug use in society has grown exponentially over the last three decades.

CURRENT DRUG SITUATION

There have been no specific national surveys on drug misuse in the UK but other national surveys have included questions on drug misuse. Sexual health and lifestyle surveys (Johnson, 1993) indicate that less than I% of the population have ever injected drugs, but that in London as many as 2% of the population may have injected drugs. The Psychiatric Morbidity Survey indicates less than I% of the population as a whole use heroin or cocaine, 1% use amphetamine, I% use ecstasy and 5 % use cannabis. It is estimated that there are approximately 150 000 opiate injecting drug users in the UK and that there may be a sizeable number of amphetamine injecting drug users. The data on this population is hard to ascertain. Of the heroin users there is significant variation in the route of administration with between 30 and 60% of those attending services reporting smoking heroin (Griffiths et al., 1994). There is presently a large heroin and amphetamine using population and separately a large section of the young population involved in hallucinogen use. Up to 30% of the population report use of cannabis but a smaller proportion report regular use of cannabis. There is a growing problem with cocaine use both among the opiate addict population and, separately, there is a growth in new markets in crack cocaine. These new markets include the AfroCaribbean population. The size and extent of the problem to date is not clear but is likely to require a significant shift of service responses to cater for the crack cocaine addict population. The number of new people entering services in the UK continues to grow.

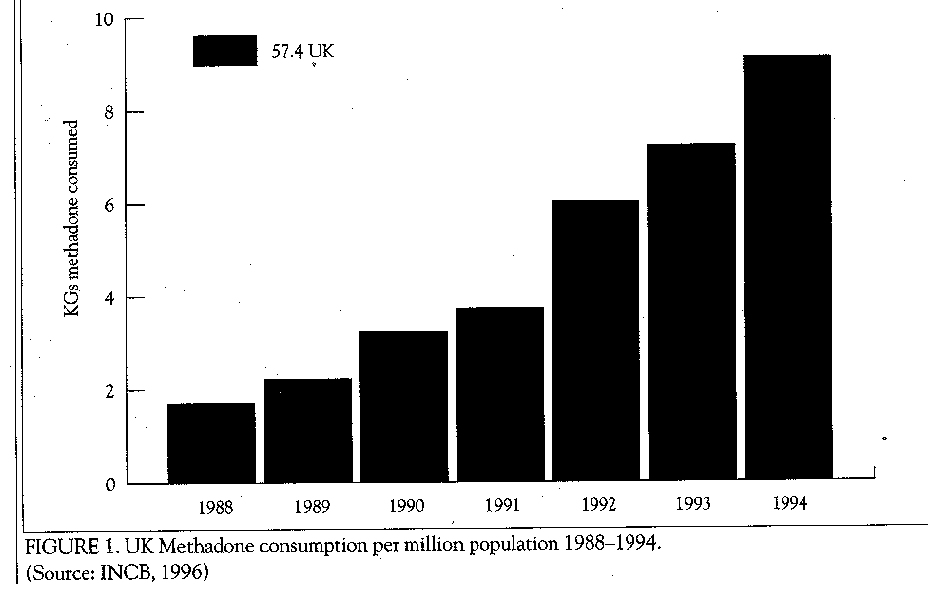

The number of people entering with stimulant type problems remains a small fraction of the overall proportion but it has grown at a substantial rate over the last few years. The general perception is that of a worsening drug problem. There has been a major growth in the number of people presenting over the past decade with a rise from 8000 in 1984 to 22 000 in 1993. The majority of these have been for opiate problems. Over 22 000 have been prescribed methadone and there has been a considerable expansion in the consumption of methadone (Figure 1). There are no clear data on the numbers receiving short-term versus long-term methadone. The services are provided by healthcare, statutory social care and the non-statutory sector. They include community drug teams/out-patient services, inpatient wards for detoxification or stabilisation of drug use, residential services for rehabilitation and day centres. The population attending these tend to be characterised by high levels of socioeconomic deprivation, unemployment, low levels of educational attainment and poly-drug abuse.

METHADONE PRESCRIBING SERVICES

The UK has a wide network of methadone prescribing services with the majority of services integrated into the mainstream of drug services and linked also to primary care services. Probably 95% of methadone prescribed is by means of a prescription issued at a hospital or community based clinic, which is then taken to community pharmacists who dispense methadone for consumption at home or elsewhere. Prescriptions are generally valid for 14dayjandthere is a recommendation that in the early phase, all drugs be dispensed on a daily basis excepting weekends. Doctors are free to exercise their clinical judgement when interpreting these recommendations. Daily dispensing from community pharmacists is a costly activity. There are no dose limits specified but practitioners prescribe doses ranging between 20 and 100 mg as oral methadone mixture 1 mg per nil. Most of the services have behavioural contracts linked to the provision of methadone. The specific contracts and stringency with which they are applied differ from service to service but include issues such as the following: no heroin use; no use of stimulants; no excessive alcohol use; and behaviour within the clinic or surgery within defined limits in terms of aggression and/or intoxication.

There are a number of services in the UK who offer on site consumption of methadone. The clinics offering this service are staffed by nurses, pharmacists and drug counsellors in addition to having medical back-up. These services typically also include the sort of behavioural contract described above. Reasons for their establishment include the research agenda, concern about methadone diversion and the desire to provide a low threshold service to the most chaotic street drug users.

There is considerable geographic variation in the level of prescribing with regions such as Merseyside prescribing for over 5000 addicts and other regions such as Oxford having low levels of methadone prescribing. Most of this activity occurs through community drug services, which are, in essence, specialist services. Community drug teams typically consist of specialist community nurses, drug counsellors, social workers and psychologists. They may have a doctor attached full- or part-time to the team: this is usually a person with general practice or psychiatric training. Alternatively, the teams may liaise with clients' own general practitioners for methadone prescribing. Up to 200/o of general practitioners may be involved in methadone prescribing but over 80% of general practitioners have no desire to be involved in substitute prescribing. There is a substantial amount of benzodiazepine prescribing with up to 30% of some service attenders reporting use of benzodiazepines, A handful of drug services offer the prescribing of dexamphetamine sulphate for the management of amphetamine addiction. There has been a consider-, able expansion in the growth of methadone detoxification for prisoners but a limited amount of methadone maintenance in prisons.

INJECTABLE PRESCRIBING

There is considerable variation in the balance between injectable and oral methadone prescribing with some regions reporting up to 10% of prescribing, in injectable form and some regions reporting minimal injectable prescribing. There is no regulation or limitation on practitioners in determining the balance between oral and injectable prescribing. There are a few private doctors in London who mainly focus on the prescribing of injectable methadone and amphetamines because of the limited prescribing of these drugs within mainstream services. To date there have been a few studies to evaluate oral versus injectable options, one exception being the randomised controlled trial in the late 1970s and early 1980s of injectable heroin versus oral methadone referred to above. The UK has a legal framework that allows the prescription by doctors who have obtained a licence for the purpose from the Home Office for heroin, dipipanone and cocaine for the treatment of addiction. A 1995 survey in England and Wales identified 42 doctors who held licences for heroin, 10 for dipipanone and 7 for cocaine. The majority of these individuals are psychiatrists specialising in addiction. Most prescribe these drugs to small numbers of patients (Sell et al., 199 5). The number of individuals in receipt of a heroin prescription has been reported to be 2 50 in the UK as a whole.

NATIONAL LEGISLATION, REGULATION AND DATA COLLECTION

Any doctor in the UK may prescribe methadone for the control of addiction. They are obliged to complete a controlled drug prescription. The Home Office drugs inspectorate in partnership with the police regularly inspects the chemists to ensure that the requirements for prescribing and dispensing are completed by both doctors and chemists and improper procedures can be pursued by the Home Office inspectorate.

Since the Dangerous Drugs Act of 1973 there has been an Addicts Index where all doctors are legally obliged to notify the people they come in contact with who are dependent on notifiable drugs, such as, heroin, cocaine, methadone but not amphetamines. Forms are filled and returned to the Home Office and these are stored in a confidential database, which the doctors may consult if they are initiating prescribing. There is a limited compliance with notification to this Index, with reports indicating that less than one fifth of contacts are notified. This data provides a range of information on drug use patterns and routes of administration of drugs. This is a national centralised information system. There is also a regional drug database-all drug services complete a form and return to a regional database collection. This carries similar information to the Addicts Index but covers all drugs of abuse. Only a small part of the data is aggregated at national level.

There have been clinical guidelines for the management of drug dependence since the mid 1980s. These are advisory guidelines specifically Aimed at general practitioners. In the specialist service deliveries and within the community service deliveries there is no specification of how frequently a patient must attend and there is no limit to the size of a client population the service may have.

EVALUATION AND OUTCOME

It has been noted that the level of HIV seroprevalence among the drug injecting population in the UK has remained low at 1-2%, with London figures running between 6 and 10%. This is seen as part of a successful HIV prevention strategy based on the development of broad-based community services and needle exchange programmes. All of these services are funded through the National Health Service and are free at the pointof access. Presently, the Maudsley Hospital has completed a randomised control trial comparing on-site methadone maintenance to community detoxification. Other studies, including one comparing general practitioner with specialist methadone prescribing, are in progress. Because of the mode of dispensing there is a major amount of diversion of prescribed medication and a large black-market on methadone where methadone costs about £10 per 100 ml. To date this diversion has not been a political issue but there are rising numbers of first service contacts reporting methadone use only and there have been anecdotal reports of deaths from recreational methadone use. A new network of structured methadone maintenance programmes commenced in 1995. The UK Goverment's Drug Strategy, Tackling Drugs Together, published in 1995, prioritises the role of drug services in reducing drug related crime. At the same time, the Government has initiated an effectiveness review task force, who reported in April 1996 on all aspects of services for drug users.

REFERENCES

ACMD (1993). AIDS and Drug Misuse: Update. London: HMSO.

Griffiths P, Gossop M, Powis B (1994). Transitions in patterns of heroin administration: a study of heroin chasers and heroin injectors. Addiction 89: 301-9.

Hartnoll R, Mitcheson M, Battershy A. (1980). Evaluation of heroin maintenance in controlled trials. Archives of General Psychiatry 37: 87784.

International Narcotics Control Board (1996). Narcotic Drugs Estimated World Requirements for 1996. Statistics for 1994. Vienna.

Johnson AM, Wadsworth J, Welling K, Bradshaw S, Field J. (1992). Commentary: Sexual lifestyles and HIV risk. Nature 360:410-2.

McGregorS (1994). The central funding initiative. In StrangJ, Gossop M (Eds) Heroin Addiction and British Policy. Oxf-)rd: Oxford University Press.

Robertson R (1990). The Edinburgh epidemic: A case study. In Strang J, Stimson G (Eds) Aids and Drug Policy. London:Routledge.

Sell L A, Farrell M, Robson PJ. (1995). Prescription of diamorphine, clipipanone and cocaine in England and Wales, submitted.

Spear B (1994). The early years. In Strang J, Gossop M (Eds) Heroin Addiction and British Policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stimson G (1995). AIDS and IDUs 1987-1993: the policy response and the prevention of the epidemic (1). Social Science andMedicine 41(5):699-716.