| Articles - Opiates, heroin & methadone |

Drug Abuse

IS THE POLICY OF ENCOURAGING GENERAL PRACTITIONERS TO PRESCRIBE OPIATES FLAWED?

Philip Fleming and Judy Morey, Northern Road Clinic, Portsmouth, UK and Peter Charlton, University of Portsmouth, UK

In recent years in the UK official reports and central government advice have encouraged general practitioners to take an active part in the treatment of opiate users. Experience from different parts of the country has presented a variable picture of the results of this policy. In some places there has been considerable success in persuading GPs to take on this task, in other places less so. A GP survey was under taken to help plan joint working and training. This revealed a number of negative attitudes held by respondents. GPs often felt inadequate dealing with drug misusers and a number of constraints to doctors getting involved were identified. The policy of GPs treating addicts is critically reviewed. It is argued that the success or otherwise of this policy is often due to local factors. Some of the disadvantages and difficulties are discussed. There is a need for more research into the outcome and cost of GP treatment Of drug misusers.

INTRODUCTION

In recent years general practitioners have been encouraged to take a more active role in the treatment of patients with drug problems (Department of Health, 199 1; ACMD, 1993; HMSO, 1995). This advice has been repeated in the Task Force Review (Department of Health, 1996). Whilst some GPs have been interested and involved in their treatment for sometime (Robertson, 1985; Wailer, 1993) others have been less enthusiastic. Surveys of GPs' attitudes to drug misusers (Glanz, 1986; Abed and Neira-Munoz, 1990) have shown that although they agree that services for drug misusers should be given a high priority most thought that the management of addiction was beyond their competence. A survey in the Northwest region concluded that in spite of being encouraged to work with drug misusers general practitioners were not doing so (Tantam et al., 1993). Nevertheless in some places successful joint working has been reported (Ford, 1993; Greenwood, 1996; Gruer et al., 1997).

Portsmouth is a city on the south coast of England whose health district covers a population of 5 50 000. There has been a specialist service for drug misusers since the late 1960s which has included substitute prescribing for opiate users (Fleming, 1988). The local policy had always been to discourage general practitioners from prescribing for addicts and to encourage them to refer drug users to the specialist service for treatment. The Health Authority, in line with government policy, was keen to encourage more joint working With GPs. However, this change in local policy was not universally welcomed and brought forth a hostile response from local general practitioner organisations. One of us (JM) had been employed as a training officer with a specific brief to work with primary healthcare teams. It was decided to undertake a survey of GP attitudes to substance misusers to help plan future joint working and training.

METHOD

A self-completion postal questionnaire was sent to all GPs in the South East Hampshire Health District. The GPs were asked to respond on a five-point scale to 24 statements. Returns were anonymous. The statements were presented twice, once in the context of drug misuse and then again, with minimal word changes, in the context of alcohol misuse. The statements used were drawn from three sources:

· The Alcohol and Alcohol Problems Perception Questionnaire (AAPPQ) was devised to assess helping agents' attitudes to alcohol-related problems (Cartwright et al., 1975; Cartwright, 1980). A subset of nine items was selected from the AAPPQ to measure an agent's overall therapeutic attitude to alcohol misuse. With minor modifications the same set of statements was used to reflect therapeutic attitudes to drug misuse.

· Second, Lightfoot and Orford (1986), extending the work of Cartwright, developed a measure of r situational constraints which they viewed as factors operating within agents' occupational contexts either constraining or facilitating the development of a positive therapeutic attitude. Six of their situational constraint items were selected. These items were modified for that part of the questionnaire relating to drug misuse.

The third source was Greenwood (1992a) who related her own extensive experience of working with GPs as a member of Edinburgh's community drug problem service. She described the attitudes and beliefs that lead GPs to avoid drug using patients. Items were formed from key phrases taken from her text. These individual statements were included as being of interest in their own right and not as forming a coherent scale. With minor modifications the same set of statements was used to reflect attitudes and beliefs in respect of alcohol misuse. Finally one statement gave the respondents the opportunity to say whether they would be prepared to discuss the issues raised by the questionnaire with other professionals.

RESULTS

The questionnaire was sent to 324 GPs; only one posting was done and a total of 134 questionnaires were returned, a response rate of 41 %. For the purposes of this paper only the responses to the statements on drug misuse will be reported. The statements can be broadly divided into three groups: hose concerned with attitudes, with competence and with constraints.

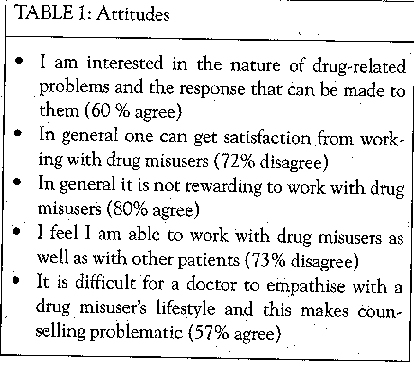

Attitudes

Respondents expressed some degree of interest in the subject, 60% agreeing with the statement: I am interested in the nature of drug-related problems and the response that can be made to them. However, there was a generally negative response to other statements reflecting attitudes (see Table I).

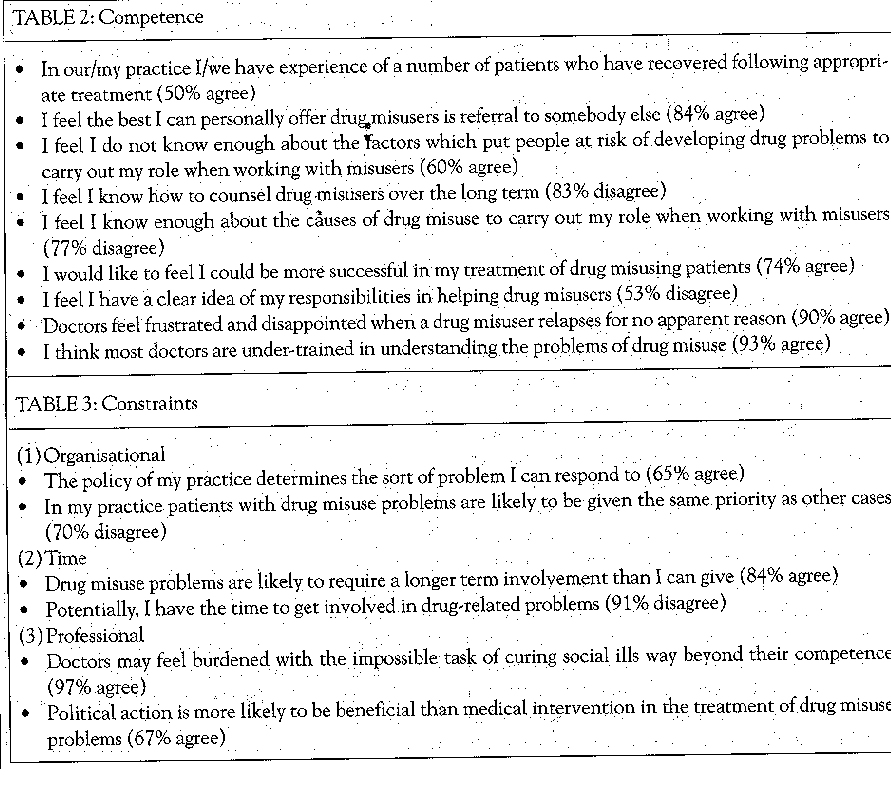

Competence

This grouping is concerned with the doctor's knowledge and experience and feeling of adequacy in dealing with drug misusers. There is not a wholly negative view of outcome; in response to the statement 'In my/our practice I/we have a number of patients who have recovered following appropriate treatment', although 21 % did not express an opinion, of those who did 500/o expressed agreement. There was otherwise a general lack of confidence in the ability of respondents to manage drug misuse The need for further training was underlined; in response to the statement 'I think most doctors are undertrained in understanding the problems of drug misuse', 93 % agreed (see Table 2).

Constraints

These statements cover different constraints on a doctor getting involved with drug misusers. There do not seem to he significant constraints at an organisational level in general practice (see Table 3). How.. ever, there are individual constraints, particularly time, for respondents. A final constraint is the limitation of medicine in dealing with problems that require social and political action.

The final statement was aimed at gauging the willingness of respondents to look further at the issues mentioned above. It was disappointing that in response to 'I am prepared to meet with other interested professionals with a view to opening discussion of the above', 15 % expressed no opinion and of those who did, two-thirds disagreed.

DISCUSSION

Care must be taken in interpreting the findings given the relatively low response rate of 41 %. The questionnaire was sent to GPs at a time when there was considerable discussion and some local hostility at a proposed change in policy to involve GPs more in the treatment of drug misusers. It may be that the responses are therefore biased towards those least disposed to work with drug misusers. The local GPs had hitherto not been actively involved in the treatment of drug misusers and there had been little in the way of postgraduate training available. Therefore it is not perhaps surprising that the respondents expressed negative attitudes. Nevertheless it is useful to consider some of the broader implications of our findings.

There are a number of reasons why GPs have been encouraged to share the care of drug users with specialist services. First, GPs are often the first port of call for drug misusers and are therefore in a position to offer help early before drug use becomes entrenched (Richards, 1988). Treatment is normalised (Greenwood, 1992b) and is part of the overall care that a GP gives to his/her patients thus avoiding the marginalisation of drug addiction treatment and bringing it into mainstream medical care. Appropriate physical care can be given, which is of particular importance in the context of HIV infection (Robertson, 1989). Drug problems affect other members of the family and the GP is well placed to see the problem in perspective (Chang, 1988). Drug users often prefer to be treated by their GPs (Bennett and Wright, 1986; Hindler et al., 1995).

Second, it is more cost effective (Greenwood, 1992b). The rapid growth of drug misuse and the number of people misusing drugs has outstripped the capacity of the specialist system of care (Tantam et al., 1993). In this situation it makes sense to use resources as effectively as possible and to reserve specialist resources for complex cases with GPs dealing with the more straightforward ones with support from the specialist services.

However, it is clear that there have been a number of problems in developing shared care, some of which are highlighted in our survey. Perhaps the most important determinant of whether effective shared care can be developed is the attitude of GPs to working with drug users and our own results mirror those obtained in other surveys. Kidd and Ralston (1993) reported on a survey of Glasgow GPs and concluded that' considerable work is needed to convince general practitioners that they should be involved'. Roche et al. ( 199 1 ) set up focus groups to investigate GPs' attitudes to drug and alcohol patients in Sydney and found opiate users were least favoured and that hostility was expressed by most respondents to them. Many GPs faced with a drug user will refer them on to a specialist agency. Bell and colleagues, surveying GPs in Inner London, found that most referred them on to specialist agencies for treatment (Bell et al., 1990). In a survey of GPs attending a seminar on addiction - presumably an interested group of doctors - a fifth would not accept a new patient on their books with a known history of addiction (Hindler et al., 1995). In a survey of London GPs King (1989) found that over a quarter would not accept a known intravenous drug user as a patient.

It is clear that doctors often do not feel competent at dealing with the problems of drug misusers and this is borne out by our results. Abed and Neira-Munoz (1990), in a survey of GPs in Norwich, found that 76% thought that the management of addiction was beyond their competence; this compared with 60% in Glanz's study (Glanz, 1986). Similar findings have been found in respect of GPs' management of alcohol problems (Anderson, 1985).

Several authors have underlined the need for more training of GPs in managing drug misuse (McKeganey, 1988; Bell et al, 1990; Telfer and Clulow, 1990; Weller et al.1 1992; Martin, 1996). As Roche points out, even if doctors are willing to intervene, to do so effectively they need to have reasonable skills (Roche and Richard, 1991). However, even if willing and possessing the appropriate skills there may be other constraints on a doctor getting involved. Our own survey highlighted the time factor. Heroin users tend to have higher consultation rates than non-users (Neville et al., 1988) and the additional workload can be considerable (Richards, 1988). Wilson, who also points to the additional workload, has calculated that the annual cost of providing methadone maintenance treatment for one patient is over 12000 per annum (Wilson et al., 1994). Central government policies are resulting in a shift in the balance from secondary to primary care (Coulter, 1995) and this is putting more pressure on general practitioners. In addition other factors are leading to a fall in the morale of GPs (McBride and Metcalfe, 1995). The net effect of all this is to discourage GPs from taking on the care of drug misusers, or, for those already doing so, to limit this work.

The development of general practitioner involvement in the treatment of drug addicts has been very variable around the UK. It has often occurred because there has been an absent or inadequate specialist service (Robertson, 1985; Martin, 1987). In Edinburgh shared care was set up as a response to a high prevalence of HIV infection amongst drug users and the previous lack of any specialist service (Greenwood, 1990). In Glasgow similarly the lack of a secondary specialist service led to the development of GP-led clinics (Wilson et al., 1994; Scott et al., 1995). In other cases general practitioners have become involved because the local specialist agencies have long waiting lists (Cohen et al., 1992). A postal survey of GPs in south-east London revealed that at least two-thirds had seen at least one opiate user in the previous four weeks and that over a quarter reported prescribing medication such as methadone for such patients (Groves et al., 1996).

Greenwood has pointed to the problem of sustaining a consistent policy in a locality if GPs are actively involved in prescribing for opiate addicts (Greenwood, 1992b). No one is immune from being deceived by an addict who wants drugs (Bewley et a]., 1975) but the GP operating on his/her own is particularly vulnerable. Substitute drugs may be prescribed to non-addicted persons. There is a danger of idiosyncratic prescribing occurring with higher doses of drugs or the prescription of injectable drugs. Ironically these concerns were noted by the Advisory Council On The Misuse of Drugs in their report Treatment and Rehabilitation in 1982 (ACMD, 1982) and which led to the issuing of the first treatment guidelines two years later (DHSS, 1984). It would be unfortunate if idiosyncratic prescribing became commonplace.

There are many places where successful models of shared care have been implemented. Generally such schemes are well coordinated, there is access to specialist advice and support and training for GPs is available (see Bury, 1995 and Gruer et at., 1997 for examples). Two positive findings from our survey were that 74% of respondents agreed they would like to feel they could be more successful in treating drug misusers and 60% were interested in the nature of drug problems and the responses that could be made to them. It is clear that as a first step we need locally to provide more education and support to GPs and to capitalise on those willing to treat drug users.

Glanz has charted the fall and rise of the general practitioner in the treatment of addicts (Glanz, 1994). The present enthusiasm is driven by the need to provide treatment to an increasing number of drug users with limited specialist resources. Many general practitioners still do not feel inclined to take on this responsibility and there are factors within general practice itself militating against a successful policy of shared care. There is a danger that these factors will lead to those doctors who do treat addicts abandoning such treatment. Equally there is a danger that uncontrolled prescribing will occur. To date there has been very little research on the outcome of general practitioner treatment of opiate addicts (Department of Health, 1996). Is it effective? Is it cost effective? The time has come to review the practical application of a shared care policy for drug misusers.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Barbara Pitman, Librarian at the Education Centre, St Mary's Hospital, Portsmouth for her assistance. We thank those general practitioners who completed the questionnaire.

Dr P.M. Fleming,

Portsmouth City Drugs and Alcohol Service, 130 Elm Grove, Southsea P05 I LR, UK.

REFERENCES

Abed RT, Neira-Munoz E (1990). A survey of general practitioners'opinion and attitude to drug addicts and addiction. BritishJoumatof Addiction 85: 131-136.

AdvisoryCouncil on the Misuse of Drugs (1982). Treatmentand Rehabilitation. London: HMSO.

Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (1993). AIDS and DrugMisuse Update. London HMSO.

Anderson P (1985). Managing alcohol problems in general practice British Medicaljouraal290:1873-1876.

Bell G, Cohenj, Cremona A (1990). How willing are general practitioners to manage narcotic misuse? Health Trends 2: 56-57.

Bennett T, Wright R (1986). Opioid users attitudes towards and use ofNHS clinics, general practitioners and private doctors. BritishJournal of Addiction 81: 757-763.

Bewley TH, Teggin AF, Mahon TA, Webb D (1975). Conning the general practitioner - how drug abusing patients obtain prescriptions. Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners 25: 654-657.

Bury J (1995). Supporting GPs in Lothian to care for drug users InternationalJournalof DTugPolicy 6: 267-273.

Cartwright AK, Shaw SJ, Spratley TA (1975). Designing a comprehensive community response to problems of alcohol abuse. Report to the Department of Health & Social Security by the Maudsley Alcohol Pilot Project.

Cartwright AKJ (1980). The attitudes of helping agents towards the alcoholic client: the influence of experience, support, training and selfesteem. BritishJournal of Addiction 75:413-431.

ChangJM (1988). Management of drug misuse in general practice. Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners 38: 248-249.

Coulter A (1995). Shifting the balance from secondarv to primary care. British MedicalJournal 311: 1447-1448.

Cohen J, Schamroth A, Nazareth I et at. (1992). Problem drug use in a central London general practice. British MedicalJournal304:1158-1160.

Department of Health ( 199 1 ). Drug Misuse and Dependence, Guidelines on Clinical Management. London: HMSO.

Department of Health (1996). Report ofan Independent Review of Drug Treatment Services In England. London: Department of Health.

DHSS (1984). Guidelines of Good Clinical Practice in the Treatment of Drug Misuse (Report of the Medical Working Group on Drug Dependence). London: DHSS.

Fleming PM (1988). Recent Developments at Northem Road and in the Portsmouth area. In Brown C, Lovelock R, Powell J (Eds) Services for Drug Users. Policy Studies Institute & Portsmouth Polytechnic.

Ford S (1993). A care package. Standing Conference OnDrug Abuse London Newsletter (November): 4.

George M, Martin E (1992). OPs attitudes towards drug, users. BritishJournal of General Practice 302. 4

Glanz A (1986). Findings of a national survey otthe roleof general practitioners in the treatment of opiate misuse: views on treatment. British MedicalJournal 293: 486-488.

Glanz A ( 1994). The fall and rise of the general practitio net. In Strang J, Gossop M (Eds) Heroin Addiction and Drug Policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

GreenwoodJ (1990). Creating a new drug service in Edinburgh. British MedicalJournal 300: 587-589.

Greenwood J 992a). Unpopular patients: GPs attitudes to drug users. Druglink (July/August 8), Institute for the Study of Drug Dependence, London.

Greenwood J ( I 992b). Persuading general practitioners t o prescribe - good husbandry or a recipe for chaos? British journal of Addiction 87: 567-575.

Greenwood J (1996). Six years experience of sharing the care of Edinburgh's drug users. Psychiatric Bulletin 20: 8-11.

Groves P, Heuston J, Durand MA et al. (1996). The identifi cation and management of substance misuse problems by gene ra I p rac t i t i one rs - Journal of Men tal Health 5 (2 183-193.

Gruer L, Wilson P, Scott R et al. (1997). General practitioner centred scheme for treatment of opiate dependent drug injectors in Glasgow. British Medical Journal 3 14: 1730-1735.

HindlerC, Nazareth 1, KingMetal. (1995). Drug users'views on general practitioners. British MedicalJournal 306: 1414.

HMSO (1995). Tackling Drugs Together, A Strategy for England 19951998. London: HMSO.

Kidd BA, Ralston G (1993). Injecting drug users in Edinburgh: GPs reluctant to prescribe. British MedicalJournal 306:1414.

King MB (1989). Psychological and social problems in HIV infection: interviews with general practitioners in London. British MedicalJournal 299: 713-717.

Lightfoot PJC, OrfordJ (1986). Helpingagents attitudes towards alcohol related problems: situations vacant? A test and elaboration of a model. BritishJournal ofAddiction 81: 749-756.

Martin E ( 1987). Managing drug addiction in general practice the reality behind the guidelines: discussion papcr.Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 80: 305-307.

Martin E (1996). Training in substance abuse is lacking for GPs. British MedicalJournal 3 12: 186.

McBride M, Metcalfe D (1995). General practitioners low morale: reasons and solutions. BritishJournal of General Practice 2 2 7.

McKeganey N (1988). Shadowland: general practitioners and the treatment of opiate-abusing patients. British Journal of Addiction 83: 3 73-3 86.

Neville RG, McKellican J F, Foster J ( 1988). Heroin users in general practice: ascertainment and features. British Medical Journal 296: 7 5 5758.

Richards T (1988). Drug addicts and the GP. British Medical journal 296: 108 2.

Robertson JR (1985). Drug users in contact with general practice. British MedicalJournal 290:34-35.

Robertson JR (1989). Treatment of drug misuse in the general practice setting. BritishJournal of Addiction 84: 377-380.

Roche AM, Richard G (1991). Doctors' willingness to intervene in patients'drug and alcohol problems. Social Science & Medicine 33 (9):1053-106 1.

Roche AM, Guray C, Saunders J13 (199 1). General practitioners'experiences of patients with drug and alcohol problems. BritishJournal ofAddiction 86: 263-275.

Scott RTA, Gruer LD, Wilson P, Hinshelwood S (1995). Glasgow has an innovative scheme for encouraging GPs to manage drug misusers. British MedicalJournal 310:464-465.

Tantarn D, Donmall M, Webster A, StrangJ (1993). Do general practitioners and general psychiatrists want to look after drug misusers? Evaluation of a non-specialist treatment policy. BritishJournal of General Practice 43: 470-474.

Telfer 1, Clulow C (1990). Heroin misusers: what they think of their general practitioners. British journal of Addiction 85: 137-140.

Walter T 0 993). Working with GPs. London: Institute for the Study of Drug Dependence.

Weller DP, Litt JCB, Pots RG et al. (1992). Drug and alcohol related health problems in primarycare -what do G Ps think? MedicalJournal of Australia 156:43-48.

Wilson P, Watson R, Ralston GE (1994). Methadone maintenance in general practice: patients, workload and outcomes. British MedicalJournal 309: 641-644.

This paper is based on a presentation given at the 7th International Conference on the Reduction of Drug Related Harm in Hobart, Tasmania in March 1996.