| Reports - Le Dain Interim Report |

Drug Abuse

CHAPTER FIVE

PRESENT CANADIAN POLICY THE LAW

A. INTRODUCTION

356. Present Canadian policy with respect to the non-medical use of psychotropic drugs is mainly reflected in a heavy emphasis on law and law enforcement. Moreover, it is an emphasis on the use of criminal law. Since this law is affecting or threatening to affect more and more Canadians in all age groups and all walks of life, it is not surprising that there should be such a preoccupation with the appropriateness and limitations of the criminal law as a means of controlling non-medical drug use. In the initial phase of our inquiry, by far the greatest proportion of the testimony we have heard has been con- '. cerned directly or indirectly with this problem. It is in the very forefront of Canadian perceptions of the phenomenon of non-medical drug use. Until our conception of the role of law in this field has been re-examined, and certain assumptions agreed upon, it is going to be very difficult to develop a coordinated and effective system of social responses to this phenomenon.

357. Law is, of course, not the only means of social response to the phenomenon of non-medical druge use. As we suggest in Chapter Six, social response runs through a whole 'gamut, including law and administrative regulation; research, information and education; various social influences, such as those of family, church, peer-group, media and entertainment; medical treatment and other supportive services; and corporate and individual responsibility and self-restraint, reflected in such matters as production, distribution and prescription of drugs. There are no doubt more. It is sufficient to observe here that law is only one of these responses, and it is far from clear what its relative importance is in the long run. It is, nevertheless, the dominant response at present, and it colours our approach to all the others. It inevitably invites special consideration at this time.

358. A full consideration of Canadian policy with respect to the non-medical use of drugs requires a detailed knowledge and understanding of how the various institutions in our society are responding to this phenomenon, particularly those in the fields of law, science, education, medicine, social ` service, and `mass communication and entertainment. We do not have that knowledge at this time although "We have glimpses of certain issues and problems on which we shall comment to a limited extent, with some interim recommendations of a :'very general nature, in Chapter Six. For example, we do not yet have a sufficiently intimate knowledge of the way in which our scientific, educational and medical institutions are responding to this problem to be able either to give a full description of current policy in these fields or to make detailed recommendations, although we believe that certain general observations aie both possible and appropriate at this time We plan to deal more fully with these matters in our final report.

359. Because, however, of the present importance of law in public perceptions of the phenomenon of non-medical drug, use, we believe that we should venture some general outline of the content and application of the law in this field.

The, statement which follows is not by any means intended to be exhaustive or definitive, but simply to serve as a sufficient background for the identification and discussion of some of the issues at this time. It also serves as a frame of reference for the interim recommendations with respect to law which we make in Chapter Six. During the ensuing year we intend to deepen our study of the law, from both a doctrinal and empirical point of view, to examine the policy and practices of other countries in greater depth than han been possible so far, and to consider more fully the policy options that are available to Canada.

360. Some of the Canadian attitudes towards the present law and law enforcement are referred to in Chapter Six to indicate the issues that have been raised during the initial phase of the inquiry, but we do not think it would be appropriate at this time, when we are less than- +half way through, to attempt a comprehensive description of these attitudes might appear to assign relative weight, in terms of popular opinion, to them. We do not yet have a sufficient basis to speak with any degree of confidence about the relative weight_ of Canadian attitudes towards the non-medical use of drugs. In the initial, phase of our inquiry, we have gathered a great variety of impressions but we have no way of knowing how representative any of them are of Canadian attitudes generally. We cannot, for example, venture "a statement of what we think to be the majority view or consensus, If } there is such a thing at the present time.

Perhaps we shall not even be in a position by the end of this inquiry to speak with assurance about the weight of public opinion on the various issues involved in the non-medical use of drugs. We hope to be able to throw more light on this subject as a result of a national survey to be carried out in 1970 (See Chapters One and Three.) This will give us some base data concerning attitudes. We hope also that our interim report and our public hearings in 1970 will draw out segments of opinion that we may not have heard from as yet, or that we may not have heard from in aufficiently representative manner. Hopefully, the interim report may assist us to focus expression of opinion and attitudes more directly upon the precise issues involved in the determination of the proper social response to the non-medical use of drugs.

361. Insofar as the other institutional responses, and attitudes towards them, are concerned—in the fields, for example, of science, education and medicine- we have reserved such descriptive observations as we are able to make at this time to Chapter Six.

B. LAW AND LAW ENFORCEMENT

I. Some Historical Background'

362. The history of Canadian legislative policy with respect to control of drugs may be traced to 1908, when legislation to control the traffic in opium was adopted,' following a report on The Need for the Suppression of the Opium Traffic in Canada by William Lyon Mackenzie King, then Deputy Minister of Labour. King had come upon the traffic in opium rather by accident while investigating claims for compensation arising out of the anti-Asiatic riots which took place in Vancouver in 1907.

363. Gradually, over the years, an increasing number of drugs were brought under the control of the Opium and Narcotic Drug Act,' and the severity of the penalties was increased. There can be no doubt that Canada's drug laws were for a long time primarily associated in the minds of its legislators and the public with general attitudes and policy towards persons of Asiatic origin. For example, in 1922 when the law was amended' to provide for mandatory deportation of convicted aliens, two members of the House of Commons expressed the hope that such deportation would help "to solve the oriental question in this country".'

364. The inclusion of marijuana in the Opium and Narcotic Drug Act in 1923' is thought to have been influenced in some measure by a book entitled The Black Candle, which was written by Mrs. Emily S. Murphy, a police magistrate and a judge of the Juvenile Court in Edmonton, Alberta. The book was based on a series of, articles on drugs which she wrote for Maclean's Magazine, and it contained a chapter which referred to marijuana as a "new drug menace". It also referred to legislation against marijuana in certain American states. It quoted statements to the effect that marijuana causes insanity and low of "all sense-of moral responsibility" and leads to violence. There is, no suggestion that the extent of use or public concern about marijuana were factors which led to its inclusion in the Act in 1923. Nor does there appear to have been any particular attempt to justify this decision on the basis of scientific evidence.

365. In 1955 a Special Committee of the Senate of Canada was appointed to inquire into and report upon the traffic in narcotic drugs in Canada.' The Committee was chiefly concerned with the opiate narcotics, particularly heroin. Its report, published in 1955, contains the following observations with respect to marijuana:1

Marijuana is not a drug commonly used for addiction in Canada, but it is used in the United States and also in the United Kingdom by addicts.

No problem exists in Canada at present in regard to this particular drug. A few isolated seizures have been made, but these have been, from visitors to this country or in one or two instances from Canadians who have developed addiction while being in other countries.

The Committee recommended more severe penalties for trafficking in the drugs covered by the Opium and Narcotic Drug Act, including "heavy compulsory minimum sentences", and a "penalty of the utmost severity" for importation.' It opposed any distinction between the addict trafficker and the non-addict trafficker and declared that the trafficking provisions should be directed to making distribution by street peddlers and addicts so hazardous that the "higher up" would have difficulty finding outlets. "The elimination of trafficking in drugs," said the Committee, "is the goal of enforcement and the attainment of this goal is not assisted by artificial distinctions between motives for trafficking." In justifying severe penalties the Committee referred, in part, to testimony by Mr. Harry J. Anslinger, U.S. Commissioner of Narcotics, before a Special Committee of the United States Senate.

The recommendations of the Special Committee on the Traffic in Narcotic Drugs in Canada were implemented in some measure by the Narcotic Control Act,' which replaced the Opium and Narcotic Drug Act in 1961. It increased the severity of the penalties for trafficking and possession for the purpose of trafficking, and imposed a minimum penalty of seven years imprisonment for importation. The Act did not, however, adopt the Committee's recommendation of a severe minimum penalty for trafficking. It also made provision for preventive detention and compulsory treatment," although these provisions of theAct have not been put into force by proclamation.

H. International Framework

366. Canadian legislative policy on the non-medical use of drugs must be viewed against the background of Canada's international agreements and obligations on this subject. The Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961,11 to which Canada is a party, provides that the drugs specified by it, including heroin and cannabis, shall be subject to a system of strict controls. More particularly, the parties to the Convention agree "to limit exclusively to medical and scientific purposes the production, manufacture, export, import, distribution of, trade in, use-and possession" of the drugs covered/by it (Article 4), and to make certain acts contrary to the provisions of the Convention penal offences. Article 36, paragraph 1, reads as follows:

1. Subject to its constitutional limitations, each Party shall adopt such measures as will ensure that cultivation, production, manufacture, extraction, preparation, bion, offering, offering for sale, distilbetion, purchase, sale, delivery on any terms whatsoever, brokera dispatch, dispatch in-transit, transport, importation and exportation drugs contrary to the provisions of - this Convention, and any other action which in the opinion of such Party may be contrary to.t provisions of this Convention, shall - be punishable offences when committed intentionally, and that serious offences shall be liable to adequate punishment particularly by imprisonment or other penalties :- °, of deprivation of liberty.

Canada fulfils its obligations under this Convention by the system of controls which it has established under the Narcotic Control Act and . the Food and Drugs Act.'As long as a state remains a party to the Convention it is bound by its terms. If it wishes to be released from a particular provision it must either obtain an amendment to the Convention, which may involve an international conference (Article 4?) or else withdraw from the Convention by giving the notice called "denunciation" in accordance with (Article 46), which reads as , follows:

1. After the expiry of two years from the date of the coming int. force of this Convention '(Article 41, paragraph' 1) any Party may, on, its own behalf or on behalf of a territory for which it has international . responsibility, and which has withdrawn its consent given in accord, ance with Article 42, denounce this convention by an instrument in p< - writing deposited with the Secretary-General...

2. The denunciation, if received by the Secretary-General on or before the first day of July in any year, shall take effect on the first day of January in the succeeding year, and, if received after the first day of July, shall take effect as if it has been received on or before the first day of July in the succeeding year.

3. This Convention shall be terminated if, as a result of denunciations made in accordance with paragraph 1, the conditions for its coming into force as-laid down in Article 41, paragraph 1, cease to exist.

367. Policy decisions with respect to the international control of drugs are developed by the Commission on Narcotic Drugs of the United Nations Economic and Social Council. The principal functions of the Commission are to assist the Council in the sùpervision of. international agreements respecting drug control and to make policy recommendations to the Council and to governments.- The Commission reports to the Council, submits draft resolutions for adoption by the Council, and makes decisions for its own action or guidance, or as suggestions for action by governments.

The membership of the Commission includes representatives; of countries which are important in the field of manufacture of narcotic drugs and the countries in which drug dependency or the illicit traffic in narcotic drugs constitutes an important problem.

The Commission has power to amend the schedules of the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961, by adding or deleting drugs. A party to the Convention may require review of any such decision by the Economic and Social Council.

The World Health Organization plays an important role in the development of international drug control policy. The Convention contemplates that the WHO will make recommendations to the Commission concerning the effects and proper classification for purposes of international control of the various drugs. The technical findings and recommendations of the WHO in this field are developed by its Expert Committee on Drug Dependence. The Commission may accept or reject the recommendations of the WHO as to the control measures to beapplied to a certain drug under the Single Convention on Narcotic drugs, 1961, but it may not modify them.

The Commission on Narcotic Drugs has now developed a draft Protocol on the control of psychotropic drugs outside the scope of the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961, which will be considered for adoption at an international conference in 1971. The draft ProtoCol contemplates the international control of drugs which presently fall in the "controlled" and "restricted" categories of the Food and Drugs Act, including the amphetamines, the barbiturates, and the hallucinogens, such,as LSD, DET and STP (DOM). It also contemplates control of tranquilizers. It is assumed that Canada will not incur international obligations with respect to the control of these drugs before it has had an opportunity to consider, the final report of our Commission.

III. Constitutional Framework

368. A proper appreciation of Canadian legislative policy, on the non-medical use of drugs also requires some awareness of the constitutional framework. Because of the limited scope of the federal power to regulate trade and commerce—one which has been confined essentially to international and interprovincial trade and commerce—federal drug legislation has rested on the criminal law power. What this means is that federal legislation, if it is to reach transactions taking place wholly within a province, probably has to have a criminal law character, whether or not an alternative type of regulation might be more desirable. The prohibitions in both the Narcotic Control Act and the Food and Drugs Act form part of the criminal law of Canada, said violations of these prohibitions constitute criminal offences. A misapprehension was evident during the course of our hearings that under the Food and Drugs Act had in some sense a different legal status or character than those under the Narcotic Control Act.

They do not, although there are significant differences in the severity of the penalties under the two statutes, and a wider opportunity to proceed by way of summary conviction instead of by way of indict- ment under the Food and Drugs Act.

369. It is doubtful if the Federal Government has any constitutional basis other than the criminal law power for a comprehensive regulation of non-medical drug use. The chief possibilities would be the general power (or "Peace, Order and Good Government" clause)' based on the importance such use has assumed for the country as a whole, and a broader application of the trade and commerce power, based on the international and interprovincial character of the drug traffic as a whole. It is doubtful, however, if either of these bases of jurisdiction could be successfully invoked to support a federal regulation of any particular drug, similar to the provincial regulation of alcohol, which involves a government monopoly of distribution as well as a licensing system.

370. On the other hand, the provinces can not create penal offences unless they are properly ancillary to otherwise valid provincial legislation. There would seem to be no doubt about provincial jurisdiction,' to develop a system of administrative regulation of a particular drug similar to that which applies to alcohol, if the Federal Government: were to withdraw its criminal law proscription of the drug, or at least permit 'local option'. But the possible 'Scope for provincial penal legislation to control the distribution and use of drugs, even in the absence of federal criminal law, is not so clear. There is some judicial support for the view that such penal provisions might be validly grafted onto provincial health legislation, but it is doubtful." The judicial authority supporting provincial liquor prohibition legislation as the suppression of a 'local evil' would appear _to be a constitutional -anomaly which could not be relied on as a basis for further prohibitions of this sort"

371. In sum, the Federal Government controls the criminal law approach to non-medical drug use and the provinces would appear to control the approach of 'legalization', involving government monopoly of distribution. The division of constitutional responsibility with respect to - other aspects of the social response to non-medical drug use in particular, research, education and treatment—also indicates the appropriateness of federal-provincial consultation and cooperation to develop a coor- dinated national policy. We touch on these areas in our interim recommendations in Chapter Six.

IV. Federal Legislation and Its Enforcement

372. 1. The Statutes and Administrative Regulation. The non-medical use of psychotropic drugs is presently regulated by the Narcotic Control Act and the Food and Drugs Act. Each statute makes a rigid, -distinction between legitimate and ilegitimate use of the drugs with which it deals. Total criminal prohibition is deemed impossible because of the desirability of the drugs for certain medical or scientific purposes. Hence one major function of the legislation is to devise a system of controls which isolates this type of legitimate use and ensures that . no leakage or diversion of the drugs for illegitimate purposes occurs. This system of controls is established by the regulations under each ' act and is administered by the -Food and Drug Directorate of the Department of National Health and Welfare.

The Department estimates the yearly requirements for legitimate use in Canada and issues permits to licensed dealers to manufacture or import certain quantities. Wholesalers can dispose of the drugs only to other licensed dealers, pharmacists, practitioners, or hospitals. The pharmacists can dispense the drugs only under a prescription which they have undertaken, reasonably, to verify. For narcotics, a prescription can be filled only once, and refilling for controlled drugs is limited. Both dealers and pharmacists are required to keep complete records of the persons with whom they have transacted business involving narcotics or controlled drugs, together with the quantities which are involved. Reports are sent to the Directorate and reviewed, and periodic audits or inspections are made to verify their accuracy. Records must be kept by hospitals, although not by practitioners. The Iatter are required to account, though, for the use made of drugs they purchase for professional treatment.

The rigid systems of controls and records is designed to enable the flow of drugs in the legitimate distribution system to be maintained and verified. If excessive amounts appear at any one point, investigation may be made of the reasons for this. The objective of, this whole effort is the preservation of the integrity of criminal law controls on all other kinds of use by preventing leakage from the legal to the illegal market.

373. The Narcotic Control Act applies to opium and its derivatives, such as heroin and morphine, the synthetic narcotics and cannabis (marijuana and hashish), which is classified as a narcotic for purposes of the Act Unauthorized possession, trafficking in, and import andexport of narcotics and cannabis, as well as the cultivation of theopium poppy or marijuana, are prohibited by the Act with penal consequences as follows:

(a) Unauthorized possession is punishable

(i) upon summary conviction for a first offence, by a fine of one thousand dollars or by imprisonment for six months or by both fine and imprisonment and for a subsequent offence, by a fine of two thousand-dollars or by imprisonment for one year or both by fine and imprisonment; or

(ii) upon conviction on indictment, by imprisonment for seven years (Sec. 3, as amended by 1969 Stat. Can., c. 41, s. 12)

(b) Trafficking is punishable upon conviction on 'indictment by imprisonment for life. (Sec. 4)

(c) Being in possession for the purpose of trafficking is punishable in the same way. (Sec. 4)

(d) Unauthorized importing or exporting is punishable upon conviction on indictment by imprisonment for life, and in any case by imprisonment for not less than seven years. (Sec. 5)

(e) Unauthorized cultivation of opium poppy or marijuana is punishable by imprisonment for seven years. (Sec. 6)

374. Unauthorized conduct with respect to certain other psychotropic drugs which are the subject of this inquiry is prohibited by the Food and Drugs Act.

Part III of the`Act, dealing with "controlled drugs" (which includes the amphetamines, methamphetamines, and barbiburates) prohibits trafficking in, and possession for the purpose of trafficking in those drugs as follows:

(a) Trafficking is punishable upon summary conviction by imprisonment for eighteen months, or upon conviction on indictment, by imprisonment for ten years. (Sec. 32)

(b) Possession for the purpose of trafficking is punishable in the same way. ,(Sec. 32)

Part IV of the Act,l° dealing with "restricted drugs" (which include LSD, DET, DMT, STP (DOM), MDA, MMDA and LBJ) prohibits possession, trafficking in, and possession for the purpose of trafficking in, these drug's as follows:

(a) Unauthorized possession is punishable

(i) upon summary conviction for a first offence, by a fine of one thousand dollars or by imprisonment for six months or by both fine and imprisonment, and for a subsequent offence, by a fine of two thousand dollars or by imprisonment for one year, or by both fine and imprisonment; or

(ii) upon conviction on indictment, by a fine of five thousand dollars or by imprisonment for three years or by both fine and imprisonment. (Sec. 40) -

(b) Trafficking and possession for the purpose of trafficking are punishable

(i) upon summary conviction, by imprisonment for eighteen months; or

(ii) upon conviction on indictment, by imprisonment for ten years. (Sec. 41)

A person may also be charged with conspiracy to traffic under S. 408 (1) (d) of the Criminal Code, which makes him liable upon indictment to the same punishment as one convicted upon indictment of trafficking under; the Narcotic Control Act or the Food and Drugs Act.

375. 2. The Role of Possession and the Possessional Offence in the Law. Both statutes have as their purpose the prevention of non-medical or non-scientific use of drugs. However, neither of them makes use, as such, a criminal offence.

Yet, under the Narcotic Control Act, simple possesion of the drug is a criminal offence. To the extent that `use' requires `possession', the effect of this Act is to make all unauthorized users criminals. The same is true of "restricted drugs" (e.g., LSD) under Part IV of the Food and Drugs Act. However, for "controlled drugs" (e.g., amphetamines) under Part III of the Act there is no such prohibition of simple possession (and thus, `use'), and the object of criminal law regulations is the distribution system.

376. Under both statutes, and for all three legal categories of drugs—narcotics, controlled drugs and restricted drugs—there are two prohibitions directed against illegal distribution: a prohibition against possession for the purpose of trafficking.

Importing or exporting is a separate offence under the Narcotic Control Act, carrying a minimum sentence of seven years imprisonment but it falls within the definition of trafficking for both "condoned" and "restricted" drugs under the Food and Drugs Act.

For purposes of the Narcotic Control Act and the Food and Drugs Act, `possession' has the same meaning that it has under the Criminal Code, where it is defined in Section 3 (4) as follows:

(a) "A person has anything in Possession when he has it in his personal possession or knowingly ;

(i) has it in the actual possession or custody of another person, or

(ii) has it in any place, whether or not that place belongs or is occupied by him for the use or benefit of himself or of another person; and

(b) 'Where one of two or more persons, with the knowledge and consent of the rest, has anything in his custody or possession, it shall be deemed to be in the custody and possession of each and all of them".

377 It has been held that there is no minimal' amount required to establish the offence of simple possession,3° but an `infinitesimal' amount found in traces of the accused's clothing has been held insufficient for conviction.' The accused must know that he has a prohibited drug in his possession. In other words, he must have the necessary intention or mens rea traditionally required for criminal responsibility.' Where the accused is charged with being in constructive possession' by virtue of the fact that another person has possession with his knowledge and consent" it is not sufficient to show mere acquiescence it is necessary to show some kind of control" over A common venture regarding the drug."

378. In their submissions to the Commission, officers of th e R.C.M.Police contended that a `possessional offence' was essential to effective law enforcement against trafficking. They claimed that there should be possessional offences for other prohibited drugs, such as the amphetamines. At the present time, we have no basis for comparing the effectiveness of the law enforcement . against trafficking, where there is an offence of simple-possession, such as in the case of heroin, cannabis, and LSD, with the effectiveness where there is not such an offence, as in the case of the amphetamines, but this is undoubtedly a diatter of importance requiring further examination, if possible. The existence of a possessional offence apparently makes it less risky to proceed for trafficking. As the submission on behalf of one division of the R.C.M.Police put it: "Our main target is the trafficker: At times we are, unable to obtain sufficient evidence for a trafficking offence, then we might proceed with a straight possession charge which helps to serve the purpose. An officer speaking for another division told the Commission that it Was difficult to have enforcement without a possessional offence. And another agreed that a possessional offence for "controlled" drugs would be beneficial for law enforcement.

379. 3. Burden of Proof. The role of possession in drui offences le also closely related to the question of burden of proof, in which the law reflects a significant departure from the traditional approach of'' criminal justice. The offence of possession, for the purpose of trafficking is important as a means of enforcing trafficking laws in the face or .the great difficulties in detecting and proving the prohibited transac+ tion. It enables the prosecution to -rely on the simple fact of posses sign, once proved, as evidence which canes justify a finding of possession for trafficking, even for "controlled" drugs for which there is not-f. an offence of. simple possession. In all three categories—narcotics,". controlled drugs" and restricted drugs'—it is provided that in a prosecution for possession for the purpose of trafficking there is first` to be a finding by the Court as to simple possession. If possession . i4" -law is found by the Court to be established on the evidence, the accused is to "be given an opportunity of establishing that he was not in possession of the narcotic (or controlled or restricted drug as the ^ease may be) for the purpose of trafficking". If he fails to do s he convicted of possession for the purpose of trafficking; if he succeeds he is convicted of simple possession or acquitted according- to t category of drugs involved.

It is obvious that, in the absence of an admission, proof of an ulterior motive such as the intention to traffic must be by way of inference from circumstantial evidence, most often the quantity of the _drug -discovered in the accused's possession." Hence the reason for putting some onus on the accused for an explanation of unauthorized possession. The serious question is the precise nature of the burden .thrown on the accused by this procedure and the extent to which it "roperates, in practice, as a departure from the traditional presumption of his innocence and other protection of the accused.

The Courts have distinguished the secondary burden of adducing evidence from the primary burden of proving a fact when all the evidence is in." The primary burden is always on the Crown to estab- lith all the elements of a crime, including the purpose of trafficking ip this offence. Because this onus always requires proof beyond k-reasonable doubt, the presumption of innocence remains unaffected. However,_ the legislation has deemed that evidence of unauthorized possession may support an inference of the mental element without any further affirmative evidence on this point, ,unless the accused gives a reasonable probable alternative explanation for his possession, whether from his own evidence, or other witnesses, or from evidence already before the Court' The Court need not draw this inference even when the accused does not adduce any evidence, but he takes the risk it will do so." In all cases, though, if the accused by arguments or eveidence of cross-examination of the Crown witnesses establishes a reasonable doubt about his alleged purpose of trafficking, he must be acquitted of the offence of possession for the purpose of trafficking.'

380. 4. The Definition of Trafficking. To traffic under the Narcotic Control Act means "to manufacture, sell, give, administer, transport, send, deliver or distribute", or "to offer to do" any of these things without authority." Under the Food and Drugs Act, Parts III and IV, applicable to controlled and restricted drugs, it means "to manufacture, se 1, export from or import into Canada, transport or deliver",

r without authority. " Thus under the Food and Drugs Act. trafficking ;includes importing or exporting, which is a separate offence calling for a minimum of seven years imprisonment under the Narcotic Control Act, but it does not include offering to do any of the things mentioned above. It is not clear whether any significance is to be attached to the absence of the words "give" and "administer" in the definition of trafficking in the Food and-Drugs Act. It is not necessary to be in possession to be a trafficker, and thus the offences of trafficking and being in possession for the purpose of trafficking are quite distinct, although they may be proved by the same facts" The offence of trafficking by offering to do so does not require actual possession of the drug which is offered "

Some attempts have been made to extend the definition of trafficking by relying on the word "transport" in the definition, and arguing that any movement of the drug from one place to another is sufficient for trafficking, but the Courts have rejected this argument, stating that the word "transport", when read in the context of other words in the definition, can not be applied to movement of the drug connected with the accused's own use.' The very fact that there are separate offences for possession, possession for trafficking, and trafficking, requires some notion, in the case of trafficking, of a transaction of some kind with another person.

The statutes express no distinction at all between qualitatively different kinds of trafficking and the Courts have not read any such distinction into the legislation. There is obviously a big difference between selling the drug for monetary consideration and giving it to a friend. Selling it at cost to an acquaintance is different from selling it to a variety of people to make a profit. Selling it on a small scale to make a marginal profit—perhaps to support one's own usage—is not the same as organizing and controlling a large entrepreneurial organization. As can be seen, trafficking activities range along a spectrum from a kind of act not far removed in seriousness from simple possession to the extensive activities of the stereotyped exploiter and profiteer whose image led to the kinds of penalties associated with trafficking. The legislature has left it to the Courts to develop sentencing policies reflecting important differences.

For the offence of trafficking, unlike that of simple possession (or possession for the purpose of trafficking), it is not necessary that the substance actually be one of the prohibited drugs; it is sufficient that it be represented or held" out to be such by the accused.

381. 5. Methods of Enforcement. Special enforcement difficulties calling for special enforcement methods, arise from the,fact that drug offences do not involve a victim, such as exists in the case of crimes against persons or property.

There are important consequences of this distinction. The victim of a crime against person or property usually complains to the police, gives them information, and assists them to commence an investigation. The police react to what they have been told about a specific offence. If, on the other hand, someone has a drug in his possession, and has bought it from someone else, , it is rare that anyone will feel affected enough to lay a complaint. Hence, instead of reacting to a specific request, the police must go out themselves and look for offences. Moreover, it is difficult to discover these offences. Because the parties to the offence or transaction are all willing participants, they can agree to carry out the prohibited conduct in a place of privacy where it is not likely to be seen either by witnesses or police officers.

This problem of enforcement has generated legal responses that are relatively peculiar to the drug context. First of all, under-the statutes, the powers of search and seizure by police officers have been radically expanded. Under the ordinary law, a person can be searched only after an arrest has been made, and in order to discover any evidence of the crime for which the arrest is made. Where there is not an arrest, there is no power to search premises without a search warrant."Again, such warrants assume specific evidence that the particular premises contain something incriminating. The point of these rules is to prevent- indiscriminate interference with privacy in an attempt to turn up evidence of a crime and to prevent such interference by requiring cogent evidence that the person or premises affected are peculiarly worthy of search, before such search is authorized by an independent judicial officer who reviews this evidence.

382. Under the Narcotic Control Act and the Food and Drugs Act, the powers of search are widened in an extraordinary way." The test to be applied remains theoretically the same—does the officer reasonably believe that there is a narcotic or other proscribed drug on the premises searched? But there is no longer a real requirement that the ` police obtain external review and confirmation of their judgment concerning this reasonable belief. Any police officer can enter and, search any place other than a dwelling house without a warrant, if he has this reasonable belief. If it is a• dwelling house, the demands of privacy require a warrant or a Writ of Assistance.

A warrant is obtained from a magistrate who is satisfied by information under oath that there are reasonable grounds for believing that there is a narcotic or other proscribed drug by means of or in respect of which an offense has been committed, in a particular dwelling house. On the other hand the Writof Assistance which was introduced in 1929, is a blanket warrant which must be issued by a judge of the Exchequer Court of Canada to an enforcement officer upon application by the Minister. It remains valid so long as the officer -retains his authority and it empowers him to enter any dwelling in Canada at any time, with such assistance as he may require, and *torch for narcotics and other proscribed drugs. As in the case of a -*arrant, he must reasonably believe that the dwelling contains the -sitircotic or other proscribed drug by means of or in respect of which an offense has been committed, but his reasons for such belief are not eviewable before the authority is conferred.

A peace officer having authority under the Narcotic Control Act or the Food and Drugs Act to enter a place and search without warrant, or to do so with a warrant or a Writ of Assistance may "with such assistance as he deems necessary, break open any door, window, lock, fastener, floor, wall, ceiling, compartment, plumbing, box, container or any other thing"; may search any person found in such place; and may 4111i7.0 and -take away any narcotic or other proscribed drug in such place, as well as anything that may be evidence of the commission of an offence under the Act.

Judicial reaction to these extraordinary powers thought to be necessary for the enforcement of the drug laws, is reflected in the words of the Ontario Court of Appeal in Regina v. Brezack,0 where it was held that a constable who reasonably believes that an arrested person has a ;- narcotic in his mouth may force his own fingers into the mouth to obtain the drug. The Court said:

... it is well known that, in making arrests in these narcotic cases, it would often be impossible to find evidence of the offence upon the person arrested if he had the slightest suspicion that he might be searched. Constables have a task of great difficulty in their efforts to check the illegal traffic in opium and other prohibited drugs. Those who carry on the traffic are cunning, crafty and unscrupulous almost beyond belief. While, therefore, it is important that constables should be instructed that there are limits upon their right of search, including search of the person, they are not to be encumbered by technicalities in handling the situations with which they often have to deal in narcotic cases, which permit them little time for deliberation and require the stern exercise of such rights of search as they possess.

The difficulties of enforcement in this field have led to another unusual practice—what is known in other jurisdictions as 'entrapment' but which may be described as 'police encouragement'. A person is encouraged by a police agent to commit an offence. It is impossible to say how extensive this practice is, but it is reflected in a number of cases.

It is unclear whether there is any lawful authority for police officers or their agents to engage, for purposes of law enforcement, in conduct which would otherwise be an offence. The decision in Regina V.Omerod" throws considerable doubt on the legality of this practice.

Should police involvement in the transaction have any bearing on the guilt of the accused? The American courts have developed the defence of 'entrapment' in order to deter overly aggressive police inotouragement of offences.* The Ouimet Committee, on Corrections bas recommended the legislative adoption of a similar defence in Canada in favour of a person who does not have "a pre-existing tntention to commit the offence"." In the case of Regina v. Shipley" the doctrine was applied for the first time to stay prosecution. The court found that the undercover R.C.M. Police officer befriended the rather 'naive' young defendant, asked_the latter to obtain drugs for him, and refused to repay a loan until it was done. The judge held that the Court had an inherent power to prevent abuse of its ptot;esses. The Courts have also considered the involvement of police agents in drug offences as relevant to mitigation of sentence."

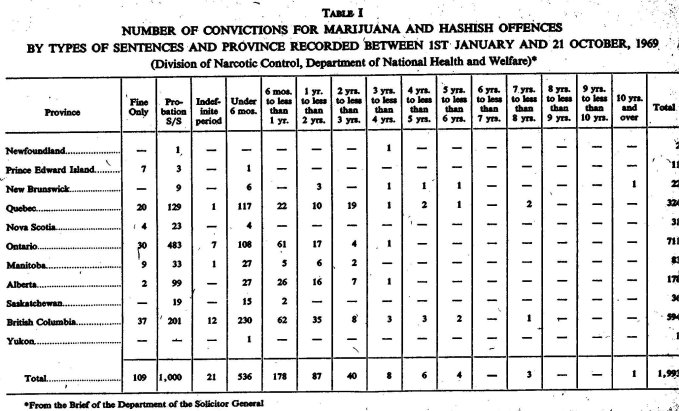

383. 6. Sentencing Policy. The approach to sentencing has varied considerably across Canada in the four or five years since offences involving drugs other than heroin have assumed importance. Table I shows the distribution and range of sentences by province for marijuana and hashish offences from January 1 to October 31, 1969," from the brief of the Solicitor General's Department.

The upsurge in drug use, especially among the young in recent year, has generated a substantial difference of opinion in the Courts as 10 appropriateness of sentences within the statutory limitations. Basically, this has involved the question of the appropriateness of prison for young first offenders, whether for possession or marginal trafficking. There have been more written, reported, appellate opinions, and MCIC discussion of the appropriate principles of sentencing policy in these drug cases than for all other offences put together. This is probably the best evidence there can be of the uneasiness the Courts feel about the difficult problem which has been left to them.

The picture of sentencing policy or attitudes which emerges from an examination of sentences over the last four or five years, prior to cases of simple possession arising under the new legislation in August 1-969," is that the provincial courts of appeal have steeled themselves against the costs to the offender and have laid down the principle that tIse 'public interest' in general deterrence calls for a substantial Prison sentence for the drug offender. Trial judges and magistrates, in actual contact with the offender, have been much more ambivalent about this policy, and in several cases prison sentences have been imposed or Increased on appeal." Probably the most influential Court in the determination of sentencing policy has been the British Columbia Court of Appeal. Beginning with the case of Regina v. Budd in 1965,4 Where the Court dismissed an appeal by a twenty-one year old female student from a six-month jail sentence for possession of marijuana, the — Court has emphasized deterrence. In Regina v. Hartley and McCalluns (No. 2) in 1968," they upheld six months terms for eighteen and twenty-one year old first offenders and spoke as follows about the significance of the offence of simple possession:,

The predominant factor in this case is the deterrent effect upon others, This Court two years ago in the Budd case ... said that the possessions . of marijuana is a serious offence and it must be punished severely. The purpose of course was to deter the use of marijuana, among other reasons, because users must obtain supplies, and the supply of the drug involves trafficking, and that, as the market increases, that traffic becomes organized, and the organized traffic tends to increase the use of the drug. It was our hope then, although I was not party to that decision, that substantial gaol sentences imposed upon people convicted of having possession of marijuana for their, own use would reduce the number of users, and consequently the trafficking necessary to supply the market. We also feared that if we did not treat this offence seriously that the traffic would continue to develop and users would increase. Our fears have been borne out by the experience over the past few years. Our hopes have been disappointed because with deference some of the members of the magisterial bench have failed to fully appreciate our purpose in the Budd case. Too many of these convictions for possession of marijuana have been treated too leniently...

In this case the deterrent aspect, as I said, is the important one. The rehabilitation of the offenders is secondary. If the use of this drug is not stopped, it is going to be followed by an organized marketing system. That must be prevented if possible. We think that is the principal consideration which should move us.

The general approach of the British Columbia Court of Appeal seems to have influenced the courts in other provinces in which prison sentences have been imposed in recent years for the offence of simple " possession. Since the amendment to the law in August, 1969, providing the option of proceeding by way of summary conviction, instead of indictment` in cases of simple possession of marijuana and hashish, sentencing policy with respect to this offence- has shown a marked change that is revealed by statistics for the balance of the year 1969. The pattern they reveal is that imprisonment is now being rarely, if at all, resorted to in cases of simple possession of marijuana and °hashish and, it would appear, LSD, and that such cases are now generally disposed of by suspended sentence, probation or fine. It would appear that the policy now is, as a general rule, not to impose prison sentences for typical first offenders. The amendment of August, 1969, applied equally to simple possession of heroin, but the information received by the Commission suggests that prison sentences are still being imposed for this offence.

As indicated above, the statute law does not make any distinction between differently motivated kinds of trafficking for purposes of penalty. On the whole, the sentencing policy for trafficking has been one of severity, with sentences in some cases of as much as 20 years." The courts have attempted to distinguish to some extent between different kinds of trafficking for purposes of sentence,' but an attempt to single out a certain category of trafficker for special treatment has beèn abandonned In Regina v. Hudson the Ontario Court of Appeal ruled that suspended sentence and probation were more appropriate for the typical typical trafficker in the youthful, alienated sub-culture of Yorkviile. The Court said:

Those, of whom the accused is one, who have accepted the use psychedelic drugs as socially desirable as well as a personally desirable course of conduct are not as likely to be discouraged by the type of punishment ordinarily meted out to other traffickers. Such treatment will likely serve to confirm them in their belief in the drug cult..

The same court reconsidered this attitude in Regina v. Stmpsok where sentences of nine months definite and six months hide e were upheld because of the alleged failure of the earlier policy. Court said:

Some six months or more have elapsed since the decision in R. Hudson and in the case at bar statistical information was intra demonstrating that the evil of trafficking in marijuana in the city Toronto is markedly on the increase, that such trafficking is into the secondary schools and that cases of such trafficking , juveniles now are a matter of frequent occurrence in the -Juvenile Courts of the city ... the protection of the public must include consideration of the interests, health and well-being of the vast majority of young people comprising individuals presently uncommitted to use of this drug. As I have said, the sentence was appropriate; it is by no means a severe one, bearing in mind the gravity with which offence must be regarded by reason of the maximum penalty of imprisonment provided by the statute.

Following this case, there were several cases in other provinces where prison sentences were imposed, and in some instances increased appeal in cases of marginal trafficking.

384. 7. Empirical Study of Law Enforcement and Correctional System. The Commission has so far been able only to make a preliminary pilot study in one major locality of actual enforcement of drug laws, but it intends in the ensuing year to carry out a comprehensive and thorough empirical study of such enfor' with particular reference to such matters as the relative cost of enforcement of the drug laws, the extent and patterns of enfo including percentage of offences dealt with and kinds of offs affected, the manner in which discretions are exercised, the attitudes of police to their role, and sentencing policies and practices.

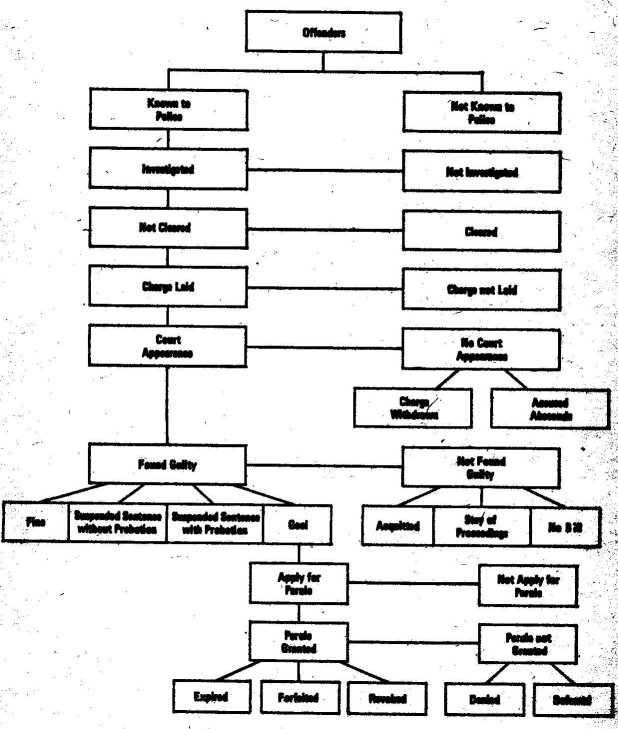

The pilot study suggests the urgent need for improvement in the present methods of collecting and recording statistical data with respect to the administration of criminal justice in this field. The kind of analysis for which reliable statistics are required is shown by model of a flow chart in Figure I. Some of the difficulties with respect to statistics arise from the fact that there are three agencies primarily responsible for the collection of data, namely: the

Food and Directorate of the Department of National Health & Welfare, R.C.M.Police and the Dominion Bureau of Statistics. The pilot study found a certain mount of chtplication, but also ism imconsistencies in the reliability and validity of information c Moreover, the delay between the conviction of drug offenders and the publication of statistical reports ranged between- two months and three years. Due to rapid changes in the nature and extent of drus use and the way in which society responds to it through its ofiicisi agencies, it is essential that this delay be reduced as much as possible. A rational policy depends on adequate, up-to-date information and steps should be taken to ensure that this is available on a continuing basis.

REFERENCES

1. Based in part upon a paper on the "Social Background of Narcotic tion" prepared by Mrs. Shirley J. Cook and others for the Alcoholism Drug Addiction Research Foundation of Ontario.

2. An Act to prohibit the importation, manufacture and sale of Opium for than medicinal purposes, 1908 Stat. Can., c.50.

3. R.S.C. 1952, c.201.

4. House of Commons Debates, 1922, pp. 2824 and 3017.

5. Opium and Narcotic Drug Act, 1923, 1923 Stat. Can., c.22.

6. Emily Murphy, The Black Candle (Toronto, Thomas Allen), 1922.

7. The Senate of Canada: Proceedings of the Special Committee on the T in Narcotic Drugs in Canada, 1955, xii.

8. Ibid., xx-xxi.

9. 1960-61, Stat. Can., c.35.

10. Secs. 15-19.

11. The Single Convention was adopted in 1961 by a plenipOtentiary conf in which 73 states participated, and it came into force on Dec. 13, 1964:: replaced all existing multi-lateral treaties in the field.

12. 1952-53 Stat. Can., c.38, as amended by 1960-61 Stat. Can., c.37; 196 Stat. Can., a15; 1969 Stat. Can., c.41; and 1969 Stat. Can., c.49.

13. Standard Sausage Co. v. Lee [1933] 4 D.L.R. 501, [1934] 1 D.L.R. 706.

14. Cf. Regina v. Synder and Fletcher (1967) 61 W.W.R. 112 and 576 (Alta. C and Regina v. Simpson, Mack and Lewis [1969] 1 D.L.R. (3rd) 597, (1' C.C.C. 101 (B.C.C.A.), rev'g. [1968] 67 D.L.R. (2d) 585.

15. A.G. Ont v. A.G. Can. (Local Prohibition Case) [1896] A.C. 348 at 370; Switzman v. Elbling and A.G. Que„ [1957] S.C.R. 299.

16. All penalties specified are maximum penalties except the minimum . - of seven years imprisonment for importing or exporting a narcotic.

17. Enacted by 1960-61 Stat. Can., c.37. s.l.

18. Enacted by 1969 Stat. Can., c.41, s.10.

19. R. v. McLeod, (1955), 21 C.R. 137 (B.C.C.A.).

20. R. v. Ling, (1954), 19 C.R. 173 (Alta.) 109 C.C.C. 306 (Alta.); but corn Regina v. Quigley, (1955), 20 C.R. 152; 111 C.C.C. 81, where it was held ,. the only reasonable conclusion was that the amount found was the rest of a larger amount.

21. R. v. Beaver, (1957), S.C.R. 531; 118 C.C.C. 129.

22. See paragraph (b) of section 3 (4) of the Criminal Code quoted above.

23. R. v. Colvin and Gladue, (1943), 1 D.L.R. 20, 78 C.C.C. 282 (B.C.C. R. v. Lacier, 129 C.C.C. 297 (Sask. C.A.); R. v. Harvey, 7 C.R.N.S. i. (N.B.C.A.); R. v. Marshall (1969), 3 C.C.C. 149 (Alta. C.A.)

24. What is required is control over the drug but this may presumably be infe from control over the person or persons in actual possession of it. Narcotic Control Act, s.8. Food and Drugs Act, s.33 (as amended by 1969 Stat. Can., c.41, s.8). Food and Drugs Act, s.42 (as enacted by 1969 Stat. Can., c.41, s.10). 28. See R. v. Wilson, (1954), 11 W.W.R. 282, but compare with R. v. MacD R. v. Harrington, (1963), 43 W.W.R. 337 (C.A.).

Other circumstantial evidence most commonly relied on are exhibits su: ing sale or distribution, such as containers, scales and measuring spoons, I of names and telephone numbers, large amounts of cash in small deno tions, and the like; and evidence of the accused's movements suggestive contact for purposes other than his regular employment.

29. See R. v. Sharpe, (1961),-O.W.N 261, 131 C.CC 75 (Ont. C.A.), a case under the Opium and ,Narcotic Drug Act,-and predecessor of the Narcotic Control Act.

30. R. v. Capello, 122 C.C.C. 342 (B.C.C.A.).

31. R. v. Hupe, Forsyth and Patterson, 122 C.C.C. 346 (B.C.C.A.).

32. R. v. Hartley and McCallum (No. 1), (1968) 2 C.C.C. 183 (B.C.C.A.); See also R. v. Hupe, et al, supra; R. v. Capello, supra. In R. v. Sharpe, supra, the Ontario Court of Appeal held that the secondary burden on the accused of adducing evidence could be discharged by a balance of probabilities, that the primary burden of proving guilt beyond a reasonable doubt rests on the Crown throughout, and that for this reason the burden on the accused was not an infringement of the right under the Canadian Bill of Rights "to be presumed innocent until proved guilty according to law".

33. Sec. 2 (i).

34. Secs. 31 (c) and 39 (d).

35. R. v. MacDonald; R. v. Vickers, (1963), 43 W.W.R. 238 (B.C.C.A.). See also R. v. Wells, [1963,] 2 C.C.C. 279, in which the accused was convicted of trafficking for her aid to a distributor who actually passed the drugs to the buyers. She drew up a list of potential buyers, received their mgney, and checked their names off the list as they received their purchase.

36. R. v. Brown, (1953), 17 C.R. 257.

37. R. v. Macdonald; R. v. Harrington, (1963), 41 C.R.' 75, 43 W.W.R. 337; [1964] 1 C.C.C. 189 (B.C.C.A.). R. v. Cushman, 5 C.R. N.S. 359.

38. See Narcotic Control Act, s.10; Fond and Drugs Act, ss. 36 and 44.

39. See Traswick, E. W., "Search Warrants and Writs of Assistance", (1962) 5 Criminal Law Quarterly 362.

40. [1950], 2 D.L.R. 265 at 270 (Ont. C.A.).

41. (1969), 6 C.R.N.S. 37 (Ont. C.A.).

42. Sorrells v. United States, 287 U.S. 435 (1932).

43. Report of the Canadian Committee on Corrections, pp. 75-80.

44. Judgement of County Court of Ottawa, October 22, 1969, not yet reported.

45. R. v. Ormerod, supra; R. v. Mills, judgement of the British Columbia Court of Appeal, May 28, 1969 not yet reported. Cf. however, R. v. Grandbois, (1969), 6 C.R.N.S. 313 in which no reference was made to the fact that the sale was made to an undercover agent. -

46. From the brief of the Department of the Solicitor General to the Commission.

47. 1969 Stat. Can., c.41.

48. E.g. R. v. McNicol, (1968), 5 C.R.N.S. 242, 66 W.W.R. 612, 1 D.L.R. (3rd) 328, (Man. C.A.); R. v. Racine, judgement of the British Columbia Court of- Appeal, April 2, 1969, not yet reported; R. v. Robichaud, judgement of, the New Brunswick Court of Appeal, November 25, 1969, not yet reported; R. v. Lehrmann, 61 W.W.R. 625, [1968] 2 C.C.C. 198 (Alta. C.A.); R. v. Adelman, [1968] 3 C.C.C. 311 (B.C.C.A.).

49. Judgement of the British Columbia Court of Appeal, January 15, 1965, unreported, but synopsized at 5 C.R.N.S. 248-9.

50. [1968] 2 C.C.C. 187 at 188-189.

51. R. v. Babcock [1967] 2 C.C.C. 235 (B.C.C.A.); R. v. Cipolla [1965] 2 O:R. 673, (Ont. CA.), aff'd. by-S.C.C., June 14, 1965. Both of these were serious trafficking cases.

52. E.g. R. v. Kazmer, 105 C.C.C. 153 (B.C.C.AJ; R. v. Campbell, (1969), 67 W.W.R. 678 (B.C.C.A.), dealing with hard narcotic cases.

53. [1967] 2 O.R. 501, 2 C.R.N.S. 189, [1968] 2. C.C.C. 43 (Ont. C.A.).

54. [1968] 2 O.R. 270; 3 C.R.N.S. 353, [1969] 1 C.C.C. 93 (Ont. C.A.).

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|