| Articles - HIV/AIDS & HCV |

Drug Abuse

HOUSING ISSUES OF PERSONS WITH AIDS

KAREN A. BONUCK, PHD, AND ERNEST DRUCKER, PHD

JOURNAL OF URBAN HEALTH: BULLETIN OF THE NEW YORK ACADEMY OF MEDICINE VOLUME 75, NUMBER 1, MARCH 1998

Dr. Bonuck and Dr. Drucker are from the Department of Epidemiology and Social Medicine at Montefiore Medical Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University, Bronx, New York. Address correspondence to Karen A. Bonuck, PhD, Assistant Professor, Department of Epidemiology and Social Medicine, Montefiore Medical Center/Albert Einstein College of Medicine, 111 East 210th Street, Bronx, NY 10467-2490.

INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW

Adequate housing for persons with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease greatly facilitates access to medical and social support services. Unstable housing situations undermine access to these services because they make it difficult to negotiate bureaucracies, file applications, and keep appointments. This may be why unstable housing and homelessness have been associated with higher rates of health care utilization among persons with HIV/AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) (PWHAs). 1, 2 National estimates suggest that as many as one-third to one-half of persons with AIDS are homeless or in imminent danger of becoming so.3 Previous research about the housing needs of PWHAs in New York4 -6 has not focused on talking to PWHAs who are most at risk for housing problems to ascertain the impact of these problems on them.

As part of an evaluation of the housing needs of PWHAs in New York State, we conducted eight focus groups in April and May 1996.' The groups were held to understand the housing problems of PWHAs at high risk for difficulties obtaining and maintaining suitable housing. Thus, while the groups were not selected to be an epidemiologic sample, they were chosen to represent populations identified by the New York State AIDS Housing Advisory Committee as having a great need for housing services, but for whom little housing information exists. The groups included substance users, ex-offenders, persons with a documented history of homelessness, and rural dwellers/ migrant workers.

The focus groups explored the following topics:

• current housing status and issues associated with seeking housing assistance;

• the relationship among HIV/AIDS, health, and housing;

• housing needs, preferences, and obstacles.

METHODS

RECRUITMENT AND SELECTION OF PARTICIPANTS

Recruitment began with a mailing to 400 statewide HIV/AIDS providers identified from the New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute mailing lists and regional HIV /AIDS organizations. The mailing explained the research project and asked agencies to serve as "hosts" from which participants might be recruited. The mailing also included a flyer to be posted or distributed to potential participants. The response was limited; accordingly, a telephone solicitation and/or follow-up call was done on a random basis to agencies located in areas of the state that did not respond to the mailing. Nine host agencies were secured, and participants were recruited for one pilot and eight focus group sessions.

Participants were recruited directly by agency staff or by self-referral to project staff from flyers posted in provider agencies. On being contacted, potential participants were screened to confirm that they were HIV positive and to assemble groups composed of the target populations. The number of participants per session was set at eight; random selection was exercised when a session had more than that number of interested participants. In all, 52 persons participated in eight focus groups, held in April and May 1996. The Appendix outlines how each group was recruited, when and where the groups convened, and characteristics of the participants. The composition of the focus groups included persons who, although self-selected, met the study's goal of representing the target populations.

The focus groups were conducted under contract with a private nonprofit agency specializing in HIV/AIDS provider training. Two senior social work staff from the agency managed the groups, although only one of the social workers facilitated a group at any given time. At the beginning of each group meeting, the purpose, format, and procedures for ensuring confidentiality were explained to participants. Each group began with an anecdote intended to put the participants at ease (we called it an "icebreaker"), such as asking participants to tell the group their favorite color and why, before the actual focus group began. All groups lasted 90 minutes. Transportation was provided for those who needed it. Participants were paid $40 at the conclusion of the session.

The focus groups were conducted using a standardized protocol developed for the project. The three general areas of inquiry were (1) current housing status and issues associated with seeking housing assistance; (2) the relationship among HIV/AIDS, health, and housing; and (3) housing needs, preferences, and obstacles. Within each of these areas, participants were asked three or four more specific, open-ended questions. Facilitators guided the discussion and sought to ensure the participation of all members.

ANALYSIS AND PRESENTATION OF DATA

All sessions were audiotaped and transcribed. While a standardized protocol structured the groups, responses and ideas often transgressed individual discussion topics. Therefore, we conducted a content analysis of the transcriptions to detect consistent themes. Two project staff independently classified responses to the specific open-ended questions according to concepts or themes that emerged rather than classifying according to predetermined categories. The number of responses that corresponded to these themes was recorded by project staff and was used to decide the organizing themes and subthemes that form the basis of this report. The transcripts were then reviewed again to identify quotations that most closely supported these themes, and the quotations were inserted into the report based on a consensus of project staff

RESULTS

EMPIRICAL FINDINGS

Description of the Sample.

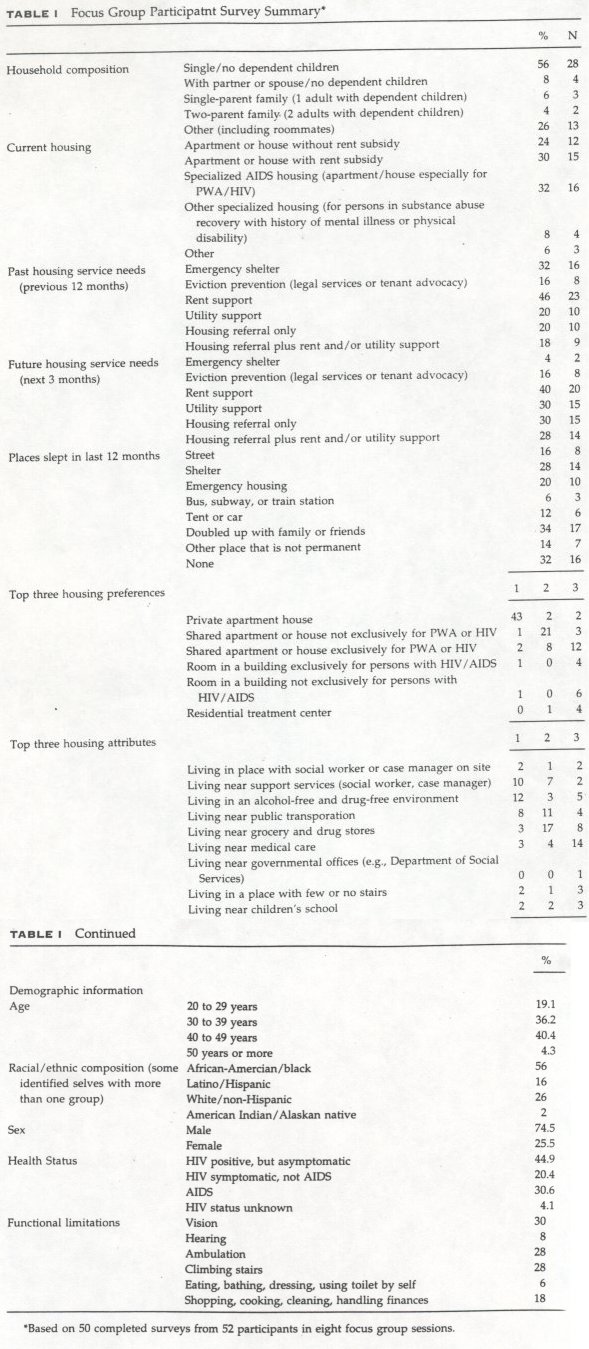

The Table illustrates responses to a brief survey admin istered prior to a group session. Given similarities among the groups, aggregated data for the 50 participants completing the surveys are shown. Thirty-six partici pants (72%) were between the ages of 30 and 50. The groups had 28 African Americans (56%) and 38 (75%) men. Twenty-two participants were asymptomatic (45%). The predominant functional limitations were in vision (n =15; 30%), ambu lation (n =14; 28%), and stair climbing (n =14; 28%). Slightly more than half the sample was single and had no children (n = 28; 56%), while 10% lived in house holds with children (n = 5).

Housing Status and Needs.

Sixteen participants (32%) resided in specialized AIDS housing, 30% (n =15) lived in private dwellings with subsidies, and 24% (n = 12) lived in private dwellings without subsidies. Rental support was the most frequently cited (n = 23; 46%) housing need in the past 12 months; 20 participants (40%) projected needing rental support in the next 3 months. Emergency shelter was needed by 32% (n =16) in the past 12 months, but only 2 persons (4%) projected a future need for it. In contrast, the 30% (n =15) projected need for utility support and housing referral only exceeded the past need of 20% (n =10). Two-thirds of the sample had been homeless or had lived in a marginal or impermanent situation in the past 12 months, such as being in a doubled-up situation (n =17; 34%), in a shelter (n =14; 28%), in emergency housing (n =10; 20%), and on the street (n = 8;16%). The overwhelming housing preference among participants was for a private apartment or house.

QUALITATIVE DATA

Circumstances Leading to Current Housing Situations.

The trajectory leading to participants' current housing entailed shifts in geographic and physical locations, as well as experience with drugs, domestic violence, and incarceration. Numerous participants mentioned spending time in New York City shelters or on New York City streets before returning to their Long Island or Upstate New York roots. When one person was asked where he had been living previously, he responded, "Where was I living? Under a highway, train station, you name it, I was there ... Maytag condominiums." Drug use was directly implicated as a reason for losing housing. For those who had been working and using drugs, drug use led directly to the loss of jobs and, with it, the ability to pay rent. The seeming random nature of housing problems is evidenced by one woman's statement that her housing problems began when her first apartment burned down 7 years before.

Several of the women arrived at their current situation as a result of domestic violence; they connected with the service system through battered women's shelters. For ex-offenders, jail liaison programs were mentioned as a useful resource. One , young man, with a history of drug use and who had been in the city shelter, was grateful for ending up in a drug treatment facility, where his HIV infection was first diagnosed. He commented, "If I was still in the street, I would be selling drugs, drinking beer. I would be nowhere.... I'd probably be dead."

Housing Assistance: First Steps, Helpful Services, and Bureaucratic Barriers.

The characteristics and procedures of helping agencies are a central feature accounting for significant differences in patients' experiences with housing needs. Community-based agencies were overwhelmingly viewed as more helpful than public agencies, which had a process of applying for benefits that was often lengthy, cumbersome, and, at times, demeaning. Church groups, AIDS organizations, and even the shelters were especially helpful in the rural areas, where they provided food and utility assistance.

The most common first step in finding help with housing was reaching a case manager. One man changed clinics to connect with a certain case manager who could secure housing for him. People frequently turned to family and friends,. although one man poignantly told how his parents let him "rot in a nursing home." Other sources of help were parole case managers and even the Yellow Pages. Among the substance users, many learned about their HIV illness while being treated for drug addiction.

There was a high degree of stress from paperwork to qualify for and find housing. For instance, transferring benefits between counties was difficult, as explained by one man who attempted to move from an Arlington housing program to one irk Niagara County. Since he was still being paid in Niagara County, he had to procure denial sheets from Arlington for supplemental security income (SSI), welfare, and disability. "It's very hard for us with the virus to go under that strain to go to welfare and get that paperwork ... it's very strenuous. I've been under a lot of strain the past few weeks. I was about to give up on my sobriety."

In terms of locating housing, a referral alone often was not sufficient. People found it helpful when agencies contacted prospective landlords for them and helped them make telephone calls to obtain benefits. The Long Island Association for AIDS Care was especially praised on this point. Participants were sometimes physically incapable of visiting potential residences on their own. A Buffalo resident with paralytic arthritis stated, "I had problems climbing the stairs to get on the bus and to get off the bus ... couldn't go to these places by myself ... that was a real barrier in that program because they didn't have transportation to take me places."

Participants benefited when agencies recognized their multiple service needs. A participant voiced appreciation that an agency realized that he needed more than just a roof, including such necessities as meals and on-site therapy. Training in life skills, such as budgeting and finances, were especially helpful to a woman who received it from the Homeless Assistance program in Buffalo. Liaison programs between prisons and drug treatment facilities were similarly needed. A young male drug treatment facility resident, on hearing how other group members secured housing after their release from prison stated, "Me, I haven't been through none of that yet.... I'm still living in the program.... That's why I'm going to be needing some information about how to get things."

Specific Housing Services.

When asked what was not helpful about services they received, we heard specific comments about the Department of Social Services (DSS); the New York City Division of AIDS Services (DAS), and Section 8 housing.* The following comments should be understood in the context of the significant burdens with which these services have had to contend in recent years. Increased caseloads, coupled with cutbacks of personnel and housing services, no doubt affected the focus group participants' experiences with these services.

*A rent subsidy program to provide lower-cost housing.

The DSS was universally seen as unhelpful. People felt that DSS forced them to contend with long lines, paperwork, and nastiness, only to be steered toward the worst housing options. People spoke of being shown dirty, drug-infested apartments that they were forced to live in until they could obtain Section 8 housing. Participants believed that unless they were assertive and specifically asked DSS about something, DSS would not help: "If you don't ask, the workers are instructed not to tell you about the benefits you're eligible for. The workers don't like their jobs and don't care." "A really bad experience," is how one woman described DSS; "every time I walked out of there, I walked out in tears." Further, DSS's 45-day waiting period was declared aggravating and stressful. One woman felt that DSS imposed it because there are a lot of food pantries; if you have lights and gas, you can wait-it is not an emergency.

In a discussion of DAS, the need for better staff education, to counteract prejudice and insensitivity, was suggested. One man complained about his caseworker, saying she began to "act like I was a disease. She would actually wear gloves around me. You know how I felt? ... The papers I had, she would not touch them. I had to throw them in her face ... A lot of these workers have no compassion. They need to get education on this or they shouldn't be working in that field." A woman said that her DAS counselor sexually harassed her by asking her explicit questions about sexual behaviors.

The 2-year waiting list for Section 8 housing was cited by participants in most of the groups as being unduly long and stressful. Once obtained, however, the Section 8 subsidy proved adequate to cover many persons' rents, although utility bills continued to be a problem. Still, it was surprising to hear that some people were fearful of putting their names on Section 8 or other housing assistance lists because they had little trust in the confidentiality laws. For example, one person said, "Buffalo, to me, is a very small and narrow-minded town ... you don't know who else is looking."

Bureaucratic rules were viewed as barriers to suitable housing. A woman who wanted to share an apartment with another single mother, with a son the same age as hers, was told that her grant would be cut. She cited Housing and Urban Development and welfare regulations as barriers. One participant was rejected for SSI five times, even though his last T-cell count was 200, not 199; he was not eligible for benefits restricted to those with T-cell counts below 200. Only after finding a doctor who would lie and enter a low T-cell count on the participant's record was the participant able to leave the shelter for a hotel. About being precluded from a certain building because he was not eligible for SSI, another commented, "You gotta be half dead until they give you $500." Another man, who was .classified as handicapped and a senior citizen (he was 55 years old), felt that getting help depended on being in the right category.

Changes in Housing Situation Since HIV Illness Was Identified.

Learning he was HIV positive led one man to depression; he was "strung out," not able to work anymore, and finally not able to pay rent: "Before you know it, housing is a problem." An Elmira participant stated it clearly: "I would like to get back to work, but my illness has prevented me from doing this." For another man, learning that he was HIV positive made him realize that he needed support: "I need supported living to be healthy ... I don't balance my budget well, I don't do my medication well."

Increased attention to hygiene and healthful habits was a common reaction to being diagnosed with HIV. Many participants mentioned that they cleaned their apartments constantly. One woman spends her own money on bottled water, fresh vegetables, and other healthy things that her congregate housing facility does not provide. Safety also becomes a concern. One man noted he did not want to be in a neighborhood in which he could be victimized because he had become very frail.

Overall, people who relied on public benefits prior to their illness felt that they had a wider range of housing options because of their HIV illness. However, one woman noted that "it's like you need a death warrant to get better housing ... can't get on SSI unless they think you are damn near crippled or have one T cell." People who had been working felt angry but resigned to the benefits they were receiving and felt that the system was "never gonna give you what you were earning to live. I live in the projects because I am HIV positive." A man receiving SSI who was unable to work stated that he was "maybe one or two rent hikes away from being on the streets again."

The HIV illness led participants to think about their future housing needs, with several stating that they had moved, or will need to move, into housing that could accommodate progressive disability. An arthritic woman who can no longer manage stairs is forced to negotiate them on her knees, with a pillow. (Although her doctor wrote a note to the housing authority last year, she had just been contacted about a ground floor apartment.) In anticipation of becoming blind, one man has learned the layout of his apartment, such as where the pots and pans are.

When asked about factors apart from HIV that affected the ability to find and maintain housing, the lack of money, particularly the inadequacy of entitlements, was primary. A woman receiving public assistance commented, "It's despicable what the government allows us to live in ... I get $153 in food stamps, and I have a 7-year-old son who eats from when he gets up to when he goes to bed." A man requiring a two-bedroom apartment for his two children only receives $334 a month for rent. In Ithaca, competing with college students for low-cost housing was a problem, as was racial discrimination. Finally, competing care giving responsibilities were cited. Referring to his mother, one man stated, "She's deaf, blind, needs oxygen 24 hours per day, and I'm her caregiver."

Effect of Housing Situations on Health.

When asked if their housing situation had affected their health, every group affirmed that it had. Most commonly, this affected their morale and ability to aggressively pursue treatment and social options, but it also directly had an impact on their nutrition, exercise, and ability to utilize family and social supports. A New York City hotel resident stated, "In the hotel, I got depressed so, therefore, my T cells went down. Just the smell alone. This happened within a week. ["I know, it's happening to me," interjected another participant.] Thank goodness I didn't have an opportunistic infection.

Those living conditions, they can actually kill us." (To this, several others agreed that they would rather live on the street than in the hotel.)

The need for money, loss of a job, and dependence on subsidies and "handouts" created considerable stress. Comments about stress were telling:

I'm under 200.... I don't need this. One day I spent 4 hours on the phone trying to figure out where my rent money was. I have four or five counselors who should have done this job. The longer I was homeless, the less I felt about George.... I know my T cells dropped drastically when I was outside.... A roof over my head relieves the stress along with the no place to cook. You have to rob Peter to pay Paul. You have to put rent first, but don't have enough to pay all your utility bills. Not having money increases your stress, which affects your general well-being.

Not having adequate cooking facilities was particularly a problem in the New York City group. A hotel resident explained: "Now I eat less, and the money they give me goes faster because I have to buy the food outside." Another resident complained: "People who are HIV positive have to have cooking facilities. We're suppose to have them. Lots of hotels don't do that, and they're beating the system."

Having enough money to pay for utilities and transportation to medical care were also issues. "We have to be able to keep our apartments heated ... to be able to cook, eat, and operate any machinery, such as an oxygen tank, which you might need to survive." The lack of adequate heat was often reported by upstate participants, many of whom reported that they got sick during the winter because of it. Living far from medical care was a hardship in all the groups. In the upstate areas, people mentioned $40 and $50 trips to see their doctors.

Supportive housing programs appeared to ameliorate many of these problems. On the positive side, people in supported living situations appeared to benefit greatly from them. A halfway house resident commented that prior to moving there he had been losing weight, but now he feels healthier.

Discrimination.

Discrimination, especially by landlords and realtors, was a major barrier to securing and maintaining housing. "I always felt that there was more going on," explained one man. "The real estate agents were fine on the phone, but once they saw how sick I was, they rushed me through the process." The experience of being turned down by prospective landlords once their HIV status was disclosed was common. Ithaca participants shared stories about a landlord notorious for discriminating against persons with HIV; they warned another participant not to reveal his status, or he would be evicted. A Buffalo participant refused several apartments because of her HIV status said that prospective land lords asked questions such as: Do you have a handicap? If so, what is your handicap? Is it diabetes, HIV/AIDS, etc.?

Discrimination in employment, making it difficult for people to become self sufficient, as well as discrimination against ex-offenders and drug users, also limited housing options. One New York City participant stated: "I don't want to get money just from the government. I want to get my own thing." As soon as prospective employers learned of his HIV status, however, they did not offer him the job. Similarly, several ex-offenders had been refused housing once a prospective landlord learned that they had been incarcerated. They found it difficult to avoid their jail/prison history when asked about previous housing.

A long drug history has definitely been a factor in determining housing location according to one man, who commented sarcastically:

Well, as long as we give him a bed and four walls and he's dry, he should be happy to get that. But the whole point of drug rehabilitation is to give me a better life. Ten years ago I had a better life when I was a functioning addict than I have now. I was teaching in a college, I was making 60 grand a year. ... Now, 10 years down the road, I have a hotel room that DAS still hasn't given me my finances for, so I'm living on $19 every two weeks and $141 worth of food stamps. So, I think they have discriminated against me besides the HIV because they think I don't deserve it or because they think I'm not capable of it.

Lack of Government Concern.

There was a shared sentiment that public agencies did not care where participants lived and exercised little oversight over the sites. "They put you in these places and you're forgotten about. Nobody comes if you've got a leak in your ceiling and in the winter you have no heat." It was suggested that agency staff view apartments first because then they would know that certain places would compromise immune systems. A New York City hotel resident noted that no telephone is available for workers to contact residents.

Participants with a history of substance abuse voiced antipathy about being steered toward drug-ridden buildings and neighborhoods. A person with substance abuse experience was shown an apartment in an area over-run with drugs: "How he want me to move there? I want to stay away from drugs." A New York City participant commented incredulously: "I'm a recovering addict, you ain't gonna put me in a trap." A current drug treatment facility resident commented: "It's like they set you up.... They don't think that you want to stay clean." A woman living in public housing projects stated: "The government puts you with drug addicts and prostitutes because they feel this is what you did to get there, so why not just put you there."

FINAL COMMENT: CRITICAL HOUSING ISSUES FOR A PERSON WITH HIV/AIDS

When asked to comment on the most important thing about housing to a person with HIV/AIDS, we received a range of responses:

• a clean, healthy environment, particularly mentioned in groups with substance users

• housing to accommodate progressive disability, including access to home health services if necessary

• proximity to medical care, transportation, groceries, and the like • housing that is not based on poverty level

• security and safety

• inspection and oversight of housing

• coordination of all housing-related services for which people are eligible

Finally, we were impressed by participants comments' about the need for confidentiality and dignity. Dignity and confidentiality can be maintained by grocery stores that deliver, as underscored by one woman, who was so embarrassed when a supermarket did not take her food stamps that she had to walk to the other side of town. "I think dignity has a lot to do with this disease, knowing that housing isn't in a sewer-ridden area," commented a participant. Stated another: "I want to die with dignity. I don't want to die in the street. Nobody asked for this disease."

CONCLUSION

We conducted a series of eight focus groups with PWHAs; the groups included substance users, ex-offenders, persons with a documented history of homelessness, and rural dwellers/migrant workers. The groups' housing needs were substantial, as evidenced by the pregroup surveys. Two-thirds had been homeless or lived in a transient setting within the past year, while one-third had needed emergency shelter.

Despite the diversity of the groups, many of their issues were remarkably similar. All groups spoke about the potent effect of their housing situation on their health. Many attributed lowered T-cell counts and increased lethargy to stress associated with governmental rules and paperwork. Another major theme was the lack of money and the inadequacy of the entitlements. According to the pregroup surveys, nearly half (46%) of the participants needed rental support in the past year. Not surprisingly, the high cost of housing was mentioned in every group.

Discrimination based on HIV status, as well as experience with the criminal justice system or drugs, made it difficult for many people to obtain apartments. Participants reported being asked about their HIV status when applying for apartments and being asked to leave once their status became known. Finally, it became clear that drug treatment plays a critical role with regard to housing. Many participants cited continued drug use as the reason for losing housing. Entering drug treatment, on the other hand, was often identified as a turning point and an opportunity to begin taking care of oneself.

APPENDIX: OVERVIEW OF FOCUS GROUP SESSIONS

Brentwood, NY. Population: homeless, substance users. This session was held at the Brentwood Presbyterian Church and hosted by the Long Island Association for AIDS Care. The association recruited group members from those participating in a common support group. Of the six participants, two were women.

Buffalo, NY. Population: homeless, substance users. This session was held at a multi-service health agency. Through a case manager, the focus group consultant recruited clients who used various services. Of the six participants, one was a woman.

Elmira, NY. Population: rural/migrant, homeless. This focus group, targeted toward rural residents, was held at the Chemung County Department of Health. Participants, recruited through a Department of Health case manager, included people receiving Department of Health services. Of the five participants, one was a woman.

Ithaca, NY. Population: rural/migrant, homeless. This group, targeted toward rural residents, was held at an AIDS organization in Tompkins County. A staff person recruited participants from its clientele. Of the seven participants, one was a woman.

New York, NY. Population: ex-offenders, substance users, homeless. This focus group was held at Exponents, Inc, a training and education organization that provides transitional counseling to clients, including (but not exclusively) persons with HIV/AIDS. Potential participants were recruited by Exponents, but the focus group consultant made the final random selection. Of the seven participants, two were women.

Rochester, NY. Population: ex-offenders, substance users. This focus group was held at the same agency as the other Rochester group. The recruitment process was the same, except that this group was drawn from participants in their in patient detoxification program. Of the six participants, three were women.

Rochester, NY. Population: substance users, ex-offenders, homeless. This group was held at a multi-service health agency. A case manager recruited clients receiving a range of agency services (i.e., housing, drug, rehabilitation, etc.). Of the seven participants, four were women

Syracuse, NY. Population: substance users, homeless. This session was held among residents of a residential program for persons with AIDS at the facility. A staff person recruited participants. All eight participants were men

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Project staff would like to acknowledge the excellent work of Signature Staff Development/ Resources (SIGNATURE) as the focus group consultant. This project was supported by a grant from the New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute.

REFERENCES

1. Bonuck K:, Arno P. Social and medical factors affecting hospital discharge of persons with HIV/AIDS. J Community Health. 19'97;22:225-232.

2. Arno P, Bonuck K, Green J, et al. The impact of housing status on health care utilization among persons with HIV disease. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1996;7(1):36-49.

3. National Commission on AIDS. Housing and the HIV/AIDS Epidemic. Washington, DC: 1993.

4. Fordham University Graduate School of Social Service and Hudson Valley Health Systems Agency. HIV/AIDS Strategic Plan for Tri-County Region. New York: Fordham Univer sity: May 1995.

5. 1995 Southern Tier Area AIDS Housing Survey. March 1995.

6. Fordham University Graduate School of Social Service Project on HIV /TB and Homeless ness. Hess H, principal investigator. July 27, 1994. Report

7. Bonuck K, principal investigator. New York State HIV/AIDS Housing Needs Assessment: Final Report to the NYS DOH AIDS Institute: August 1996.