| Articles - HIV/AIDS & HCV |

Drug Abuse

Argentina: Discrimination and AIDS prevention

Mario Pecheny

Institut Gino Germani

University of Buenos Aires

National Scientific and Technical Research Center

This e-mail address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it

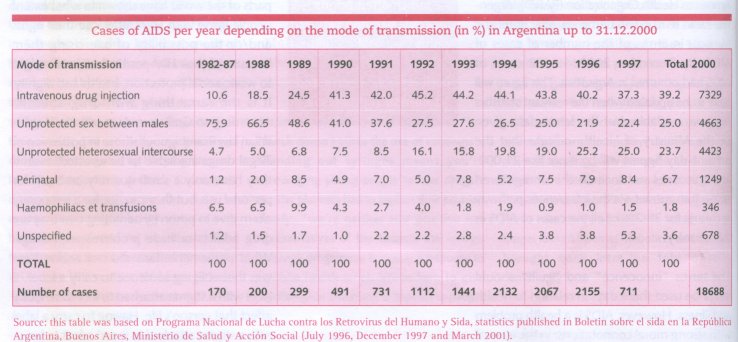

Argentina has the third highest AIDS figures in Latin America, after Brazil and Mexico. More than 39% of these cases were due to contamination via the intravenous pathway. Personal risk awareness does not suffice to stop the epidemic, since other factors are also responsible.

Given the confusion which often reigns in people's minds between health care and social and moral values, AIDS is both a public health and a human rights issue

The main illegal substances used in Argentina are marijuana* and cocaine*, whereas the use of other drugs such as heroin* and LSD* is almost negligible. The possession of illegal drugs, even for personal use, is punishable by law. Since there is a stigma attached to drug taking in many circles, drug-users are liable to undergo dual ostracism: they are both engaged in unlawful behaviour and failing to uphold prevailing social values. According to the PanAmerican Health Organization (PARO), Argentina ranks third in Latin America, after Brazil and Mexico, in terms of the number of cases of AIDS. By December 2000, 18,688 cases of AIDS had occurred in Argentina. This figure will have to be updated when the relevant statistics become available, but the latest data given by the Ministry of Health indicate that the present-day figures will be more like 21,000, and this does not include the unregistered cases. Transmission via the intravenous pathway accounts for 39.2 % of all the cases of AI DS in this country.

The terms "innocence" and "guilt" should never be used these days in relation to health and illness. However, AIDS is a health problem with strong moral connotations: in the eyes of society, there is a distinction between "innocent" patients (children, and people who have received blood transfusions), and "guilty" patients, who "had it corning to them" (people infected via the sexual pathway or by sharing syringes). Given the confusion which tends to occur between the realm of public health and that of social, moral and even legal values, AIDS is both a public health problem and a human rights issue. Studies on AIDS in various parts of the world have shown to what extent people living with HIV/AIDS lose their rights and/or the possibility of exercising them because of their HIV-positive status: the right to work, social protection, health and dignity. It is the same thing with drug abusers. According to Guillermo Aureano (1), Argentinian law is ambiguous: those in possession of illegal drugs are liable to be arrested, even if they have only a small quantity on them for personal use, but they can opt for a temporary alternative to prison by admitting that they are drug addicts or have problems with drugs. What parliamentarians did not realise here was that obliging someone to carry a label -a label with a stigma attached to it- can seriously affect that person's life. Having to carry a label with a stigma attached to it and admit to beinga drug addict not only to various criminal authorities, but also to the family and at the workplace, is a very powerful, decisive experience for individuals to have to go through.

Discrimination and exclusion only increase the risks taken by those stigmatised in this way.

The stigmatisation of drug-taking practices is sometimes thought by users themselves to be quite fair. In a survey on resident drug-users undergoing treatment at three specialised centres in Buenos Aires, the respondents said that they had experienced strong social rejection of drug users and strong prejudice against the physical appearance associated with drug taking (2). According to a survey about AIDS on 1600 people inhabiting four Argentinian cities, the study population ranked intravenous drug use first among the factors responsible for spreading the AIDS virus (3). In addition, 70% of 400 intravenous drug-users agreed that they were the main group responsible for spreading the HIV virus (3). We can see here how society and even the stigmatised groups themselves set epidemiological data against a pre-existing scheme of interpretation according to which drug taking is classified as immoral and seen as a threat to social law and order.

Discrimination and exclusion are factors which actually, increase the probability that individuals will behave id a way which endangers their own and other people's health. Among the 400 drug injecters from four Argentinian cities interviewed (3), 80% said they shared or had shared syringes, although 94% knew that there; was a high or very high risk of contracting HIV in this way. Among these respondents, 42 % said they shared injection equipment regularly with others (72% with, friends, 38% with acquaintances and 22% with their partner); 60% had on occasion done nothing to disinfect their needles and syringes; among the remaining 40%, half washed their needles with water, 28% with alcohol and only 1 % with bleach.

There is therefore quite a gulf between knowledge and concern in the abstract, and actually taking precautions in situations where there are risks. The reasons given; for the repeated use of syringes were as follows:

a) priority was given to taking drugs over the risk of infection: "it's easier to share than to go out to buy them";

b) the difficulty of obtaining syringes: "You walk round in circles and can't make up your mind to go to the . chemist's"; "I was ashamed to go out and buy 106, syringes"; "Some chemists won't sell them to me because they know I shoot myself and I'm afraid they'll call the police";

c) the pleasure of sharing;

d) fear of causing a hostile reaction from their peers if they refuse to share;

e) the context: "I'm afraid because I'm in a public place and I haven't time to go and buy them";

f) trust in friends who take drugs.

The AIDS epidemic has become such an emergency situation that it is urgently needed to act here and now. The distinction therefore definitely needs to be made between campaigns against inveterate drug addiction and AIDS prevention campaigns.

1 Aureano (G.), Entrevista, La maga, Buenos Aires, 24.12.97. 2 Kornblit(A.L.), Mendes Diz(A.M.) et Bilyk(A.), Sociedad y drogas, Buenos Aires, CELA, 1992.

3 Kornblit(A.L.), et al., Y el Sida està entre nosotros. Un estudio sobre Actitudes, creencias y conductas de grupos golpeados por la enferedad, Buenos Aires, Corregidor, 1997.

HARM REDUCTION: THE BASIC PRINCIPLES AND SOME COMPARISONS

Abstentionist policies on AIDS are designed to eliminate high-risk behaviour. To prevent sexual transmission, abstinence and stable monogamous relationships are recommended, and to reduce intravenous drug use, it is proposed to stop these practices and prosecute users. Harm reduction policy is based rather on the assumption that drug use will continue despite prosecution and preventive efforts. Instead of proposing to put a complete end to drug taking, the aim here is to reduce the risks and the harmful effects of drugs on health. As far as AIDS is concerned, the focus is on using condoms during sexual intercourse and on using syringes only once when injecting drugs. The measures proposed so far on these lines have ranged from the prescription-free sale of syringes to programmes for distributing drug substitutes.

Harm reduction policies mainly target drug injecters who are practically or completely out of touch with medical and social services. The following hierarchy of objectives has been put forward:

a) don't start taking drugs;

b) if you have started taking drugs, have treatment to stop or reduce intake;

c) if you can't cut down, stop injecting and take drugs in some other way:

d) if you inject, use sterile equipment for every injection; e) if you can't use sterile equipment, don't share syringes and needles;

f) if you share equipment, disinfect it with bleach (although it is still questionable whether this procedure is effective).

There are several arguments in favour of harm reduction policies. First, it has been recognised that the spread of HIV is a greater, more urgent threat than drug abuse and that abstentionist policies have not proved to effectively curb the spread of the epidemic. Secondly, risk reduction policies have proved to be at least as effective as abstentionist policies in terms of the numbers of drug users treated and cured. Thirdly, risk reduction policies are comparatively more effective methods of reducing the criminal behaviour associated with drug use and preventing HIV transmission (1). Lastly, contrary to what some people have feared, it has been established in several studies that risk reduction policies have not encouraged drug use (2). In our opinion, harm reduction policies are therefore definitely more effective methods of preventing the transmission of HIV than abstentionist policies.

In addition, effective prevention policies are based on the assumption that drug users are capable of responding rationally to information and public health services. The responsibility of the individual user, who can make decisions (if there are any options available) and change the more critical aspects of his or her drug use, must therefore be recognised. M.P.

1 Marks (J). Dosagem de ma nutencao de heroma e cocaine. In Robeiro M. ct Seibel S. coord. Drogas : a hegemonia do cinismo. Sao Paulo, Memorial, 1997.

2 Lurie (P), Reducao de danos : A experiéncia norte-americana. In Robeiro M. et Seibel S. coord. Drogas : a hegemonia do cinismo. Sao Paulo, Memorial, 1997.