| Articles - Education and Prevention |

Drug Abuse

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF DRUG POLICY 1993 4 2

GOING BEYOND EDUCATION TO MOBILISING SUBCULTURAL CHANGE

Sam Friedman from New York considers how drug users can organise to consolidate the behaviour changes already achieved and move on toihe second-generation tasks of maintaining those changes and preventing new injectors from starting high-risk behaviours.

This article was previously published, by the Dutch National committee on AIDS and is published here with their kind permission.

Many projects that aim at risk reduction among drug injectors see their task as one of education. This view is outdated - most drug injectors know about most HIVrelated risks, and to a large extent they have already implemented behavioural changes to reduce those risks that education will affect. Thus, we face'second - generation'tasks - producing additional risk reduction once the original changes have been put into effect; maintaining them and preventing new injectors from starting high-risk behaviours.

Considerable evidence exists that drug injectors assist each other in implementing risk reduction - i.e. peer pressure is important, and risk reduction involves changing subcultural norms rather than just individuals. Indeed, peer pressure was a factor in shaping how drug injectors have responded to the initial news about AIDS, and it continues to mediate how drug injectors respond to AIDS projects and to the developing epidemic.

So far, risk reduction has been only partial. Additional effi)rts are needed both to produce and to mainain more complete reduction in risk. A major approach to such greater risk reduction is what we have called 'encouraging subcultural changes'- i.e. creating a situation where drug users will themselves provide the positive and negative sanctions that promote risk reduction.

Drug users' organ isa tions in Europe, Australia and the USA have attempted to change users' subcultures, norms and environment to do this. In pursuit of __ goal, they have held open meetings at which users have discussed the threat of HIV and how drug-taking practices should be changed to meet it. They have produced newsletters and videos in conj unction with other membets of the scene, and used these as tools to educate and to involve drug injectors in risk reduction and infurther educational efforts. They have established syringe exchanges and outreach programmes on their own, and they have lobbied for public funding for such programmes. They have demonstrated to encourage social welfare policies, drug abuse treatment policies, and police regulations that respect drug users' dignity and that, in some cases, make it more feasible for drug injectors to reduce their risks of acquiring or transmitting HIV and other viruses.

Any project that attempts to change the norms, values, or interests of a subculture or subcultures, and thus to change the behaviours that are supported and rejeced by subculture members, needs to understand (1 ) the subcultures it is dealing with; (2) its own developing role; and (3) ways to act so as to produce subcultural change. Practitioners and theorists of social movements and community and labour organising have developed useful insights on these issues. Here, we will attempt to apply these perspectives to develop a framework for thinking about changing drug injectors' norms.

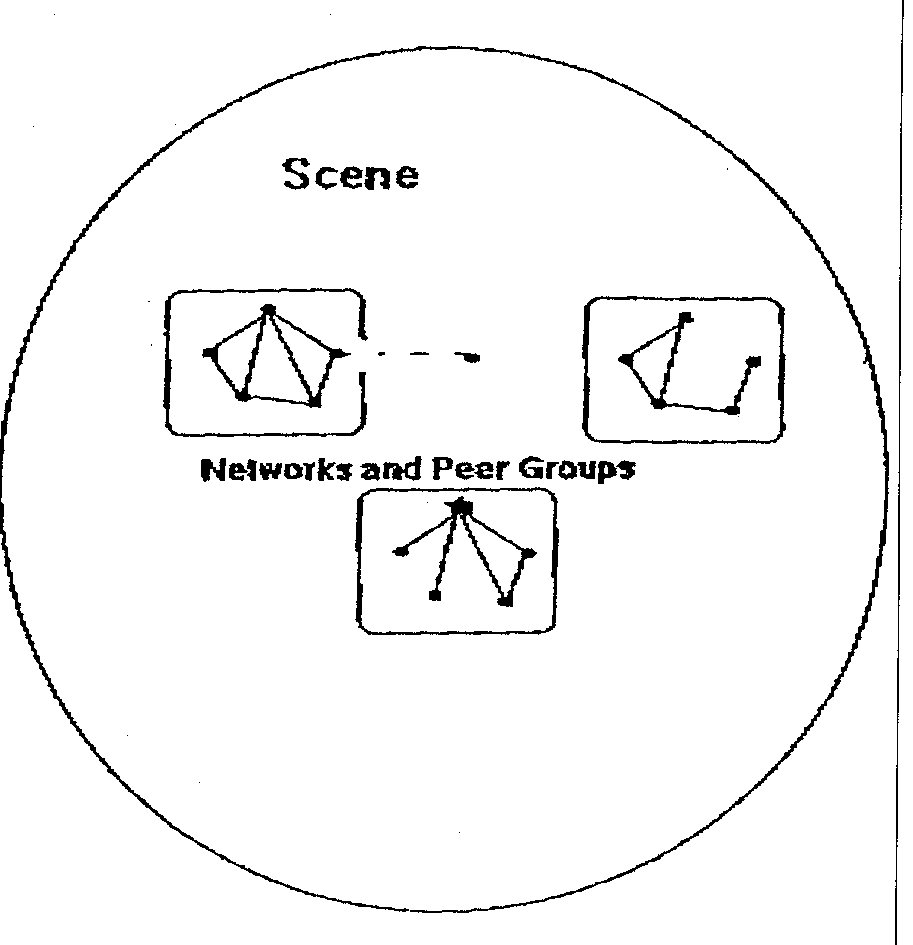

SCENES

Let us start with a brief description of salient factors of drug scenes (Figure 1). Although education-focused projects approach drug scenes as collections of individuals to be taught facts about HIV and skills with which to reduce their risk, this model is far too simple for interventions that aim to change norms. We need to look at the structures of drug scenes, and at ways to study those structures as we intervene. Drug scenes consist of varying degrees of open street scenes and of hidden users. We know little about the hidden users, although projects such as the needle exchange in Boulder, Colorado, USA, have been developing ways to work with them. The more open scenes, on the other hand, are better understood. They contain structures for dealing drugs, as well as networks and peer groups. Networks of users are a major component of the scene, and within these networks there are peer groups. 'Local leaders' exist both within many peer groups, and, sometimes, on a network basis. Working with such local influentials is a critical part of changing norms in a scene.

FIGURE 1 Drug scenes and some of their component structures

Social relationships in drug scenes vary widely. In our studies in New York, it has become clear that many drug injectors continue to maintain close relationships with other intravenous drug users (IDUs) whom they have known since they were growing up. Thus, there are long-term relationships of 10 or 20 years'duration. Here, clearly, concern for each other and peer pressure are at a maximum. On the other hand, many relationships are much shorter term, indeed evanescent, where users who barely know each other will team up to buy a bag of drugs and share it. In such evanescent relationships, peer pressure may need to take a more internalised form- in a shared street code that there are ways in which one injects drugs, and ways that are not acceptable.

Further, the outside environment is an important part of all drug scenes, and the relationships of users to the outside deeply affects their relationships to each other and to AIDS projects. Most saliently, police pressures and the use of undercover police agents make it hard to earn and retain trust. In addition, the generalised disdain that outsiders have for drug injectors means that respect for the dignity of the user is a critical value for any intervention effort - and, we might add, one that many ex-users have trouble with. Finally, of course, there are the invisible enemies - HIV and other viruses.

One last point about drug scenes. They change. Ethnographic accounts sometimes underestimate the extent to which scenes change and have histories. In New York scenes in the last 20 years, however, many large-scale changes have occurred - the widespread use of injected cocaine, the influx of crack, and other changes in the drugs being used, including changes in the purity, price and availability of various drugs. Second, the institutions of drug scenes change. Indoor shooting galleries were once major institutions in New York scenes. Insomepartsof the city,however, shooting galleries have declined. Instead, people inject in a variety of outdoor settings - many of which may be just as likely to spread HIV and other viruses across networks as shooting galleries were. Finally, of course, HIV has led to changes in norms and also, in New York at least, to a widespread new form of death and misery among drug injectors.

PROJECTS

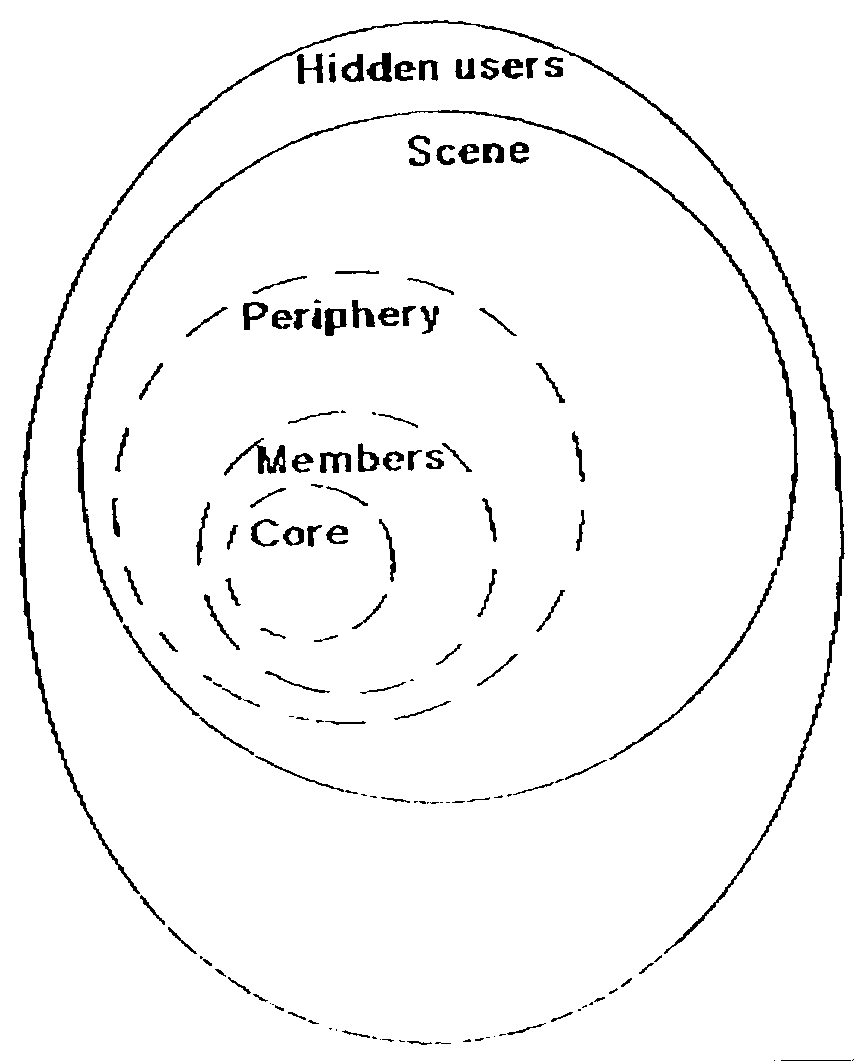

Now, let us turn to projects. Here, we will take the drug users' organisation as the prototypical project involved in trying to change the subculture - although much of what we say here can be applied to other forms of projects such as needle exchanges or outreach projects as well. When they begin, users'groups are typically a handful of users with only a small amount of influence over other injectors (Figure 2). They need to gain acceptance and respect, and to find ways to develop good ideas about risk reduction, and to have those ideas accepted and implemented throughout the scene.

Here, then, we want to introduce a set of concepts that are useful in thinking about how drug users'organisations (or other projects) can increase their influence. An organisation usually develops a core group of people who see it as an important part of their lives and who spend a lot of time on it. This core group may include paid staff and/or elected leaders, but ideally goes far beyond that. Many organisations set up a formal status of 'membership'. Other projects rely not on members, but on'regulars'. In either case, these are people who develop a serious commitment to the organisation and its goals, and spend some time trying to implement them.

FIGURE 2 Schematic representation of drug users' organisations and relevant terminology

Any organisation that is doing much begins to attract other people to its periphery. They may attend an occasional meeting, or drop into its storefront occasionally, or j ust help the members on various tasks in the streets. They are very important - a large periphery can be essential in embodying and transmitting patterns of behaviour, and also in helping organisation members stay in touch with the rest of the scene.

TASKS AND STRUCTURES

There are many aspects of task and structure that need to be discussed. Ideally, a combination of research and experience can be brought to bear on each of these issues. Here, we want to highlight a very limited set of task and structural issues. In discussing them, we rely on what has been learned through the experience of and research about other movements and organising efforts, as well as on our observations of drug users' organisations, their problems and their successes.

How to decide what the new norms should be

The epidemic sets out certain parameters. Some of these we already know, such as the need to make it illegitimate to pass on used works or to accept used works. Others, we may discover, such as the dangers of'frontloading' (see Jose et al., 1992). In other cases, we know the problem in a general way - that sexual transmission can occur, and can be greatly reduced by consistent condom use; however, there are serious issues in how to legitimise condom use, how to legitimise insistence on condom use, and then how to de-legitimise sex without condoms. On the other hand, it is one thing to know that these are what need to be done, and another to get the scene to accept these norms and then to enforce these norms. Here, what is needed is considerable discussion among the organisation's members, between the organisation and its periphery, systematic attempts to engage other drug users in discussions, with particular attention to involving local leaders of various kinds, and perhaps even some open meetings at which decisions will be made about what is and is not acceptable.

One result of meetings on these issues, of course, will be increased awareness of barriers and obstacles to risk reduction. Thus, drug users' organisations are likely to find that they are mandated by the scene to lead the following struggles: to ensure access to sterile works at all hours; to ensure access to fresh running water; to reduce or eliminate police harassment of injectors at the times and places where they are taking drugs so that they can do so safely; and, in places where many users are homeless, perhaps for access to homes.

How to enforce the new norms

There will he resistance to risk-reduction norms. Here, the question to ask is how this resistance can he broken down. In part, simply by mobilising as much of the scene as possible behind the new norms, and letting the power of example and argument sway others. Here, consistent work with local leaders, trying to involve people from all parts of the scene in the activities of the drug users' organisations and imaginative shows of support for the new norms (e.g. symbols one can wear that show the knowledge that one does'safe drugs'a,nd'safe sex') may be part of the solution.

In addition, communications and watchfulness are needed. When someone learns that a peer group or network is disobeying the norms, friendly but firm social pressure should be brought to bear. At the moment, of course, this may seem absurd - i.e. in cities where the great majority of users still continue to take certain risks, and the scene is relatively violence-torn, this degree of social influence for the users'group and for risk reduction will be slow to develop.

How to gain influence for the users' group

Here, part of the answer is simply openness and training, i.e. the users'group has to avoid becoming an isolated clique. It needs to find ways to involve more and more of the scene in its activities. In part, this can be done by going to the scene, and involving its leadersand others in discussions and other activities. Newsletters can be extremely useful here - and their main value is not in what they say (although that too is important) butrather in getting participation from as manypartsof the scene as possible in writing for it, or in being interviewed for it, and in producing and distributing it. Furthermore, project storefronts and gathering spots should be 'open spaces' where any user is made welcome, where fun is had and where lots of discussion goes on informally. Members and periphery should be involved in activities that offer training to them indeed, a main function of the core is to help others develop their talents for leadership and for risk reduction.

Meetings should be held on a periodic basis both to make decisions for the group and to discuss issues of interest. Meetings should be run democratically in a way that makes people want to attend other meetings. Although neither research nor experience provides a detailed guide as to how this can best be done, they do suggest a few gu idelines. Everyone should have a say: no one should feel as though his or her views were disregarded, whether on the winning side of a vote or not; meetings have to get things done (both in terms of accomplishing important tasks and in terms of helping participants develop skills or understanding); and meetings should be fun.

Nevertheless, we should not play down the difficulties of winning and holding respect from the scene. To do S01it will be necessary for the project to show that it supports the scene against all of its perceived enemies but to avoid taking sides in normal rivalries and disputes within the scene. In particular, drug users'organisations (and other projects that aim for widespread normative change in the scene) will sometimes have to defend the dignity of drug users against their detractors, and may have to intervene in issues over police and legal tactics and strategies. This will be clearest in cases where authorities act in ways that interfere with risk reduction efforts - for example, if police arrest needle exchange personnel or distributors of project newsletters, confiscate sterile syringes or condoms, or break up meetings of drug users' organisations called to discuss AIDS. In other cases, the issues may be less clear cut for example, if drug users' organisations solicit support from scene members for a campaign to improve drug abuse treatment, or to change the drug laws. Such efforts may cause embarrassment for funding agencies but they may well be an essential part of organising the scene for risk reduction. Here, an analogy may be helpful. The agencies that fund research find it important and valuable to fund the'indirect costs'of the organisations that conduct the research. These include general organisational overhead salaries, rents and the like. In the struggle to reduce the spread of HIV, providing support for the 'indirect efforts' of drug users' organisations to win support among drug injectors may well be essential.

Structure

Organisational structure is an important but difficult topic. In general, structure needs to be appropriate for the tasks being attempted, and as users'groups change their tasks over time it is important to reconsider questions of structure. Here, the distinction between an organisation that is trying to change subcultural norms and one that is trying to provide educational or other services is important. A service organisation needs to make its functioning routine and to provide accountability to funding agencies. An organisation that is trying to change norms and subcultures has a much higher priority on involving the scene, respecting the scene and its members, and activating and mobilising the scene. Thus, these different tasks require different organisational forms. Service agencies usually have a board of directors that makes decisions, and a paid staff to carry them out, but this is efficient only for carrying out service-provision tasks.

Users' groups need democratic involvement and openness. There are many issues to be worked out here - for example, to what extent should only members get to vote on decisions? If so, what are the criteria for membership? But the general point, that mobilising a scene for action orfor change requires having the scene members be able to take part in the organisation, and to see it as something they can have a fair say in, is suppotted by the experience of community organisers, labour organisers and social movements throughout the world.

SUMMARY

In conclusion, then, 1 want to emphasise a few points:

Risk reduction involves changing the norms, perceptions and interests of the scene and its members.

Thus, these proj ects should not be thought of as education projects, but rather as attempts to mobilise and organise members of a scene to change the ways in which they conduct highly valued and, often, secret or intimate activities.

Mobilising and organising for subcultural change requires ways to involve the members of the scene. Here, the local leaders of the scene need to be won over or socially pressured to support and enforce risk-reduction norms. This means that they need to be involved in figuring out what these norms should be, and how to enforce them.

The concepts introduced about how to think about organisation - in terms of a core, a membership, a periphery and a scene - are useful in planning organisational forms and strategies in mobilising the scene and its leaders for such change.

Needless to say, any effort to mobilise drug users for risk reducing subcultural change presupposes that the organisers have a deeply rooted respect for the capacities of drug injectors to implement risk reduction and to care about their own health and that of others. Such respect goes against the grain of much current public discourse, and also contradicts the tenets of certain forms of drug abuse treatment programmes. Nevertheless, such respect is both necessary on the part of projects that are trying to bring about risk reduction and, crucially, warranted by the history of drug users'efforts to reduce HIV risk during the epidemic so far.

Samuel R. Friedman, National Development and Research Institutes, Inc. (formerly Narcotic and Drug Research, Inc.), New York, USA.

REFERENCE

Jose, B., Friedman, S.R., Neaigus, A., Curtis R. and Des Jarlais, D.C. (1992) 'Frontloading' is associated with HIV infection among drug injectors in New York City. Oral presentation, VIIIth International Conference on AIDS, Amsterdam, July, 1992.