| Articles - Dance/party drugs & clubbing |

Drug Abuse

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF DRUG POLICY, VOL 7, NO 2,1996

ARE RAVES DRUG SUPERMARKETS?

Alasdair J.M. Forsyth, Centre for Drug Misuse Research, University of Glasgow

Using data from 135 participants in the Glasgow Dance Drug (Rave) scene, this paper intends to detail Patterns of obtaining drugs (scoring) at raves. It was intended tc confirm or reject the hypothesis that such dance events are 'drug supermarkets'. That is places where a range of drugs are more readily available than elsewhere and to which consumers will travel in order to obtain drugs. Compalisons were made between respondents who obtained each drug at a rave and those who obtained them elsewhere. In this dance, drug group all drugs were more often obtained in locations other than a rave event. Furthermore, obtaining drugs prior to attending a rave (getting sorted) was as common a practice as scoring in the rave setting. Instances of drugs being scored at a rave to be used elsewhere were rare. From these data it is concluded that it would be inaccurate to describe raves as drug supermarkets.

INTRODUCTION

Unlike previous patterns of drug use, dance drug use takes place in public. The locations where such displays of public drug use take place have become commonly known as raves. This conspicuous pattern of drug consumption has lead to sections of the media and local authorities coming to regard rave events as 'drug supermarkets'. In Glasgow, for example, throughout the history of the dance scene the local media have singled out raves as places where drugs are readily available. Newspaper headlines have included'Drug Deals at the "Acid" Disco: I'm shocked says Wet Wet Wet man', Daily Record 13/11/88;'CITY DISCO LINK TO DEADLY DRUG', Glasgow Evening Times 31/01/90; "'Party packs" put youngsters at risk on the techno-dance scene', The Scotsman 13/09/94; and 'Crooked dealers con rave kids', Daily Record 18/10/94. This latter article even utilised the well,worn xenophobic drug stereotype of foreigners or outsiders entrapping innocent local youngsters (Kohn, 1992; Melechi and Redhead, 1988; Redhead, 1991). In this instance the outsiders were dealers from England peddling fake drugs at Scottish raves. As happened with previous media fanned'moral panics'about the welfare of youth (Cohen, 1972), a legislative reaction to these events was precipitated. In Glasgow local anti-drug campaigns targeting the dance scene have included 'Drug-sh ie Id' and 'Club, watch'. Undercover police have saturated local dance events and organisers have been threatened with suspension of their licence should they fail to cooperate.

As no empirical research into dealing at raves had been carried out in Glasgow, are these actions justified? The question remains as to whether raves are drug supermarkets or merely places where people are obviously under the influence of drugs? If there are a lot of drug users at raves then perhaps it should of charge. follow that demand for drugs would be high at these locations. Dealing at a rave might also be seen to be taking place in a relatively overt fashion when compared with more traditional behind- closed- doors drug dealing. The resulting increased perception of drug availability at raves might in turn attract other users or dealers to these events, only to score or sell drugs and not to participate in dancing. If this is the case then raves may indeed be drug supermarkets.

The term drug supermarket has been applied elsewhere to refer to areas of a city or locales within such areas where drugs are known to be conspicuously available. In such drug supermarkets, users and deal, ers may either take up residence or may frequently commute there in order to sell or obtain drugs. Curtis et al. (1995) details such a drug supermarket in the Bushwickarea ofNewYork, USA. Intheirstudy, the drug supermarket operated at a street level with intravenous users being the customers. Being labelled as a drug supermarket was seen as a catalyst for neighbourhood change (decline). It is possible that in much the same way as a neighbourhood of New York might be labelled a drug supermarket so might rave venues. The labelling of raves as drug supermarkets by police, politicians or the media might also result in changes in the nature of such events.

Research in the UK dance scene has revealed a change over time in the pattern of dealing at raves. This has happened as the dance drug scene moved from'underground acid house parties'to mainstream clubs, where traditional drug dealers could become involved in dance drug supply (Newcombe, 199 1, 1992). Supply of ecstasy in the acid house scene of 1988, was not by organised crime but by independents such as 'Abby the ecstasy dealer' described by Dornet al. (1991). Abby supplied drugs for ideological motives rather than profit. Such changes in the type of drug dealer associated with the dance scene might also influence the range of drugs on sale. The current paper also asks, if raves are drug supermar, kets, which drugs are available there and which are not?

In this paper the lay term of 'scoring' drugs will be used when referring to obtaining drugs, rather than buying, as many users in this sample last got drugs free

METHOD

Data were collected from a sample of 135 respondents, who were interviewed between I December 1993 and 31 August 1994. The entry criterion for this sample was participation in the Glasgow dance drug scene Crave scene'). Respondents were recruited via purposive snowballing by using key contacts active inthe Glasgowrave scene. These keycontacts were people who 'worked' in the rave scene in the West End of Glasgow such as; DJs, electronic musicians, youth workers, drug dealers or researchers. Thesamplehadameanage of 24years (range 14-44) and was 62% male. A fuller description of this sample is published elsewhere (Forsyth, 1995).

Instrument

A structured instrument was administered listing questions about 16 specific categories of drugs and up to three other drugs that might have been taken but which were not listed. The 16 drug categories specified were: alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, heroin, buprenorphine, dihydrocodeine, temazepam, diazepam, solvents, cocaine, amphetamines, LSD, psilocybin, nitrites, ketamine and ecstasy. For each drug that a respondent had ever used they were asked a range of questions about the circumstances of their last use of this drug. Last use of each drug was chosen as a measure rather than a typical use so as to avoid any tendencies respondents mayhave had tomisrep, resent the circumstances of their drug use. Respondents were asked about the setting where they last took the drug. If this was at a dance event they were then asked for the name of that club, rave or party. Similarly, respondents were then asked where they obtained each drug, dance event or not. This is an adaptation (to account for the advent of dance drug culture) of a method previously successfully employed elsewhere to measure levels of availability and dealing patterns for different drugs (Forsyth et at., 1992).

RESULTS

Availability at dance events

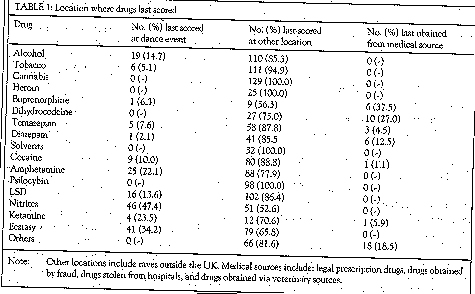

Locations where drugs were last obtained were subdivided into those obtained actually at a dance event and those obtained elsewhere. Table 1 shows which drugs were scored at raves and which in other locations. Shown separately are drugs obtained from medical sources. It can be seen that in 6 of the 17 drug categories (cannabis, heroin, dihydrocodeine, solvents, psilocybin mushrooms and the other drugs) no respondents last obtained at a rave. Obviously the location where a drug is scored need not always be the setting in which it is used. With regard to dance events three relationships between scoring and using are possible:

1 . Drugs are used at the same location as they are scored. In the case of dance events this could be regarded as 'in house' drug use.

2. Drugs may be purchased at a dance event and used elsewhere. In the dance scene this is known as getting 'take-aways'. Such scoring behaviour would fit the drug supermarket hypothesis.

3. Drugs may be obtained elsewhere in advance of attending a dance event. This practice of planned drug use scored in advance is known in the dance scene as getting 'sorted'.

'Who's in the in house?': Scoring and using at dance events

Given the large number of respondents who used drugs in a dance setting, the most obvious location where drugs might be obtained was at a dance event. Indeed, 87 (64.4%) respondents last obtained at least one of the drugs listed at a dance event, However, none of the drugs listed were obtained at a dance event by the majority of users and only nitrites were most often obtained at a dance event. There was a large degree of correspondence between those drugs used in the dance scene and drugs obtained there (see Forsyth, 1996).

'Take me away': Scoring at dance events and using elsewhere

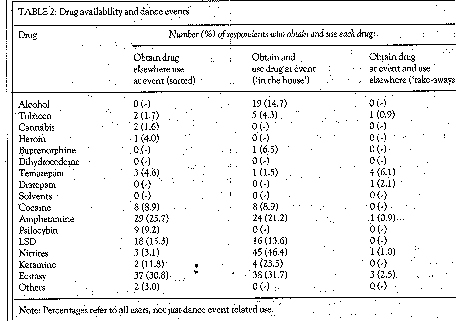

From Table 2, itcanbe seenthat thispracticewas relatively uncommon. This was most often the case with temazepam which was 'taken away' by four of the five respondents who last obtained it in a club. Though this number is small it is suspected that this drug often being obtained as a take-away might be related to its use as a'come down'drug after raving.

Ecstasy was taken away by three respor~dents and tobacco, diazepam, amphetamine and nitrites by only one person each. No respondents reported alcohot, cannabis, heroin, buprenorphine, dihydrocodeine, solvents, cocaine, psilocybin, LSD, ketamine or any drugs in the other drugs category as being take-aways from a club when last used.

'Sorted for E's and wizz': Scoring before but using at dance events

A much more common occurrence was the practice of being'sorted'before the dance event. This means obtaining the drugs prior to attending the club or rave. In such cases, the drug would usually be ingest, ed before entering the dance event, to avoid detection by door staff, timing the onset of drug effects with anticipated time of arrival on the dance floor. It was also stated that at some clubs it was easier to gain entry as a non-member if you were obviously under the influence drugs.The logicbehind thisbeing, that door staff were likely to think that someone on drugs would 'fit in' at the club and were unlikely to be a drunk, a hooligan, an undercover police officer, journalist or drug researcher. The practice of obtaining drugs outwith the dance scene and using them at a dance event was found with 12 of the 14 drugs that were last used at a dance event (i.e. all drugs other than dihydrocodeine, diazepam, or solvents, which were not used at a dance event by any respondents the last time that they were used). The two excep, tions to this were alcohol (N = 19) and buprenorphine (N = 1), where all use at a dance event was obtained at that event (i.e. neitherof these twodrugs were sorted before hand nor used as take,aways). In the case of alcohol this is unsurprising given that licensed premises (clubs) sell alcohol and do not allow patrons to bring it in with them.

The drug that was obtained elsewhere and used at a dance event by the largest number of respondents was ecstasy. Thirty,seven (47.4%) of the 78 ecstasy users who last used that drug at a dance event were sorted before the event. This was also the case with each of the other illegal drugs commonly used on the dance scene. Similar proportions were found with LSD, where 18 (52.9%) of 34 dance event users, amphetamine 29 (53.7%) of 54 dance event users and cocaine 8 (50.0%) of 16 dance event users last obtained the drug in a location other than a dance event. This practice was found in only three (6.3%) of 49 cases of nitrite use at a dance event. This presumably reflects nitrite legality (it is often sold over the bar in night clubs) and also the way bottles of ~poppers' are passed around the dance floor. Drugs less commonly used at dance events were also on occasion obtained elsewhere before being used ot an event. This was the case for two respondents ofthe five who last smoked tobacco at a dance event, three of the four who last used temazeparn at a dance event and two of the six ketarnine users who last used at a dance event. Both respondents who last used cannabis at a dance event obtained it elsewhere, as did all nine who last used psilocybin in a dance setting and two instances of drug use in the other drugs category. Clearly a rave setting is not one where a diverse range of drugs is likely to be obtained. These results are summarised in Table 2.

DISCUSSION

Although drugs are available at dance events, it might be misleading to label such locations as drug supermarkets. This is evidenced by the practice of getting sorted being commonplace. If drugs were readily available at raves then one might expect there to be tittle need to score drugs in advance. In contrast, take-aways, or instances of scoring drugs at a dance event and using them elsewhere, were retatively uncommon. This infers that users who intend to continue drug use after the rave, at say a chill. out party, are confident of obtaining supplies elsewhere after leaving the rave venue. Clearly dance drugs are widely available from sources other than dealers at raves. That said, the numbers of respondents who last used cocaine, LSD, amphetamine or ecstasy at a dance event and who also scored, in house, were similar to the numbers who were sorted for these drugs beforehand. Other (non-dance) drugs were seldom sorted before or scored at a dance event. From these data it would appear that the range of drugs available at raves is somewhat restricted. This also tends support to the rejection of the drug supermarket hypothesis. At worst, raves might be described as'specialist shops' rather than supermarkets, as only certain (mainly dance) drugs are available to only some people. Focusing drug enforcement at raves might be ineffective if dance drug scoring is a diverse rather than single situation-specific activity. For example, police action aimed at curbing dance drug use may be more effective if city-centre pubs used as pre-club venues were raided rather than just raves. However, as many non-drug users frequent such pubs, this course of action may attract less support from the general public.

From these findings it would appear that dance drug users have an option of either ensuring drug use by getting sorted or chancing being able to score drugs after gaining entry to a rave venue. Whether the decision to get sorted or wait and see is related to rave venue door policy is not known. However, the large number of users obtaining and using drugs in this way suggests that, even if it were possible to keep drugs and dealers out of raves it is impossible to exclude persons under the influence of drugs from raving. The benefits of club door searches are therefore somewhat dubious. Users might put themselves atgreaterriskby ingesting larger doses of drugs immediately prior to entering a club, rather than being able to judge gradual increases in dosage from conditions in the club. The climate of fear created by the possibility of undercover police being present at the rave venue may also influence choices about where to score drugs and when to ingest them. Other dangers are likely to arise from policies that effectively encourage drug scoring in advance of raves. Obtaining supplies from dealers outside the dance scene may increase the risk of ravers coming into contact with other drug using groups with all the risks that this might entail. In other words, fewer dealers such as Abby (Dorn et al., 1991) and increased interaction between dance drug users and the criminal underworld. For these reasons, policies aimed at eliminating drug use at raves are not only likely to fail, but may even prove counterproductive in tackling the spread of problem drug use.

Alasdair J.M. Forsyth, Centre for Drug Misuse Research, LilybankHouse, University of Glasgow, GI 2 8RT. 2. Data were collected while the author was employed at the University of Glasgow on a Scottish Office grant K/OPR/2/2/Dl25, now held by Dr Jason Ditton of the Scottish Centre for Criminology and Dr lain Smith of Gartnavet Royal Hospital Glasgow.

CONCLUSION

Clearly drugs are available at raves. However, most users obtain supplies from other locations. This is the case even for dance drugs such as amphetamine and ecstasy. Drugs were often obtained before attending raves to use while dancing. In contrast, drugs were seldom obtained at raves for use elsewhere. As such it is concluded that it would be inappropriate to label raves as drug supermarkets.

NOTES

1. The Centre for Drug Misuse Research is funded by the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Home and Health Department. The views reported in this paper do not necessarily reflect those of the Scottish Home and Health Department.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper comprises part of the author's PhD thesis. The author would like to thank Dr Neil McKeganey as supervisor of this thesis. Thanks are also due to Sally Haw, Phil Dalgarno, Furzana Khan and Emma Short for their assistance during fieldwork, and tothe respondents who participated in this research. Finally, thanks to the Beatmasters, Capella and Pulp.

REFERENCES

Cohen S (1972). Folk Devils and Moral Panics. London: McGibbon & Kee.

Curtis R, Friedman SR, Neaigus A, Jose B, Goldstein M, I ldefonso G (1995). Street-level drug markets: Network struc, ture and HIV risk. Social Networks 17: 229-49.

Dorn N, Murj i K, South N (199 1). Abby the ecstasy dealer. Druglink6:14-15.

Forsyth AJM (1996). Places and patterns of druguse in the Scottish dance scene. Addiction 91: 511-2 1.

Forsyth AJM (1995). Ecstasy and illegal drug design: A new concept in drug use. International Journal of Drug Policy 6: 193-209.

Forsyth AJM, Hammersley RH, Lavelle TL, Murray KJ (1992). Geographical aspects of scoring illegal drugs. British Journal of Criminology 3 2: 292-309.

Kohn M (1992). Dope Girls: The Birth of the British Drug Underground. Lawrence & Wishart: London.

Melechi A, Redhead S (1988). The fall of acid reign. New Statesman and Society 23rd & 30th December, 21-3.

Newcombe R (1991). Raving and Dance Drugs. Rave Research Bureau: Liverpool.

Newcombe R (1992). The use ofecstasyand dance drugs atrave parties and clubs: Some problems andsolutions. Department of SocialWork and Social Policy: University of Manchester: Manchester.

Redhead S (1991). Rave off: Youth subcultures and the law. Social Studies Review 1: 92-4.