| Articles - Crime, police & trafficking |

Drug Abuse

PRESUMED GUILTY

The Law's Victims in the War on Drugs

Pittsburgh Press, Aug 11, 1991

By Andrew Schneider and Mary Pat Flaherty

First published in the Pittsburgh Press August 11-16, 1991

It's a strange twist of justice in the land of freedom. A law designed to give cops the right to confiscate and keep the luxurious possessions of major drug dealers mostly ensnares the modest homes, cars and cash of ordinary, law-abiding people. They step off a plane or answer their front door and suddenly lose everything they've worked for. They are not arrested or tried for any crime. But there is punishment, and it's severe.

This six-day series chronicles a frightening turn in the war on drugs. Ten months of research across the country reveals that seizure and forfeiture, the legal weapons meant to eradicate the enemy, have done enormous collateral damage to the innocent. The reporters reviewed 25,000 seizures made by the Drug Enforcement Administration. they interviewed 1,600 prosecutors, defense lawyers, cops, federal agents, and victims. They examined court documents from 510 cases. What they found defines a new standard of justice in America: You are presumed guilty.

About the Authors

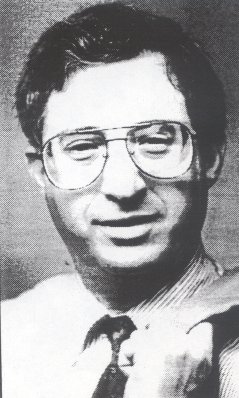

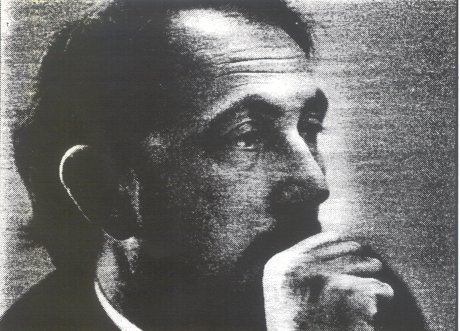

Mary Pat Flaherty, 36, is a graduate of Northwestern Univer sity who has worked for 14 years at The Pittsburgh Press where she currently is a special editor/news and a Sunday columnist.

In 1986, she won a Pulitzer Prize for specialized reporting for a series she wrote with Andrew Schneider on the international market in human kidneys. She was the first recipient of the Distinguished Writing Award given by the Pennsylvania Newspaper Publishers Association; twice has won writer of the year awards from Scripps Howard and has received numerous state and regional reporting awards.

Her assignments at The Press have included coverage of the 1988 Olympics in Seoul and a 5week trip through refugee camps in Africa.

Andrew Schneider, 48, be gan reporting for The Pittsburgh Press in 1984. Since that time, he has won two consecutive Pulitzer Prizes; in 1985 for the series he co-wrote with Mary Pat Flaherty on abuses in the organ transplant system, and in 1986, for a series, with Matthew Brelis, on airline safety, which also won the Roy W. Howard public service award.

His other work includes a series with reporters Lee Bowman and Thomas Buell on safety problems of the nation's railroads and a series with Bowman, exposing deficiencies in Red Cross disaster services.

Before joining The Press, he worked for UPI, the Associated Press and Newsweek. He is the founder of the National Institute of Advanced Reporting at Indiana University.

Part One: The Overview

Government Seizures Victimize Innocent

February 27, 1991.

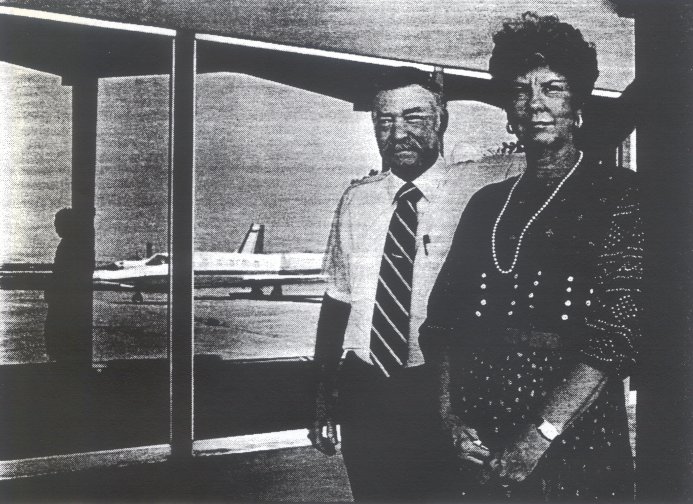

Willie Jones, a second-generation nursery man in his family's Nashville business, bundles up money from last year's profits and heads off to buy flowers and shrubs in Houston. He makes this trip twice a year using cash, which the small growers prefer.

But this time, as he waits at the American Airlines gate in Nashville Metro Airport, he's flanked by two police officers who escort him into a small office, search him and seize the $9,600 he's carrying. A ticket agent had alerted the officers that a large black man had paid for his ticket in bills, unusual these days. Because of the cash, and the fact that he fit a "profile" of what drug dealers supposedly look like, they believed he was buying or selling drugs.

He's free to go, he's told. But they keep his money -- his livelihood -- and give him a receipt in its place.

No evidence of wrongdoing was ever produced. No charges were ever filed. As far as anyone knows, Willie Jones neither uses drugs, nor buys or sells them. He is a gardening contractor who bought an airplane ticket. Who lost his hard-earned money to the cops. And can't get it back.

That same day, an ocean away in Hawaii, federal drug agents arrive at the Maui home of retirees Joseph and Frances Lopes and claim it for the U.S. government.

For 49 years, Lopes worked on a sugar plantation, living in its camp housing before buying a modest home for himself, his wife, and their adult, mentally disturbed son, Thomas.

For a while, Thomas grew marijuana in the back yard -- and threatened to kill himself every time his parents tried to cut it down. In 1987, the police caught Thomas, then 28. He pleaded guilty, got probation for his first offense and was ordered to see a psychologist once a week. He has, and never again has grown dope or been arrested. The family thought this episode was behind them.

But earlier this year, a detective scouring old arrest records for forfeiture opportunities realized the Lopes house could be taken away because they had admitted they knew about the marijuana.

The police department stands to make a bundle. If the house is sold, the police get the proceeds.

Jones and the Lopes family are among the thousands of Americans each year victimized by the federal seizure law -- a law meant to curb drugs by causing financial hardship to dealers.

A 10-month study by The Pittsburgh Press shows the law has run amok. In their zeal to curb drugs and sometimes fill their coffers with the proceeds of what they take, local cops, federal agents and the courts have curbed innocent Americans' civil rights. From Maine to Hawaii, people who are never charged with a crime had cars, boats, money and homes taken away.

In fact, 80 percent of the people who lost property to the federal government were never charged. And most of the seized items weren't the luxurious playthings of drug barons, but modest homes and simple cars and hard-earned savings of ordinary people.

But those goods generated $2 billion for the police departments that took them.

The owners' only crimes in many of these cases: They "looked" like drug dealers. They were black, Hispanic or flashily dressed.

Others, like the Lopeses, have been connected to a crime by circumstances beyond their control.

Says Eric Sterling, who helped write the law a decade ago as a awyer on a congressional committee: "The innocent-until-proven- guilty concept is gone out the window.

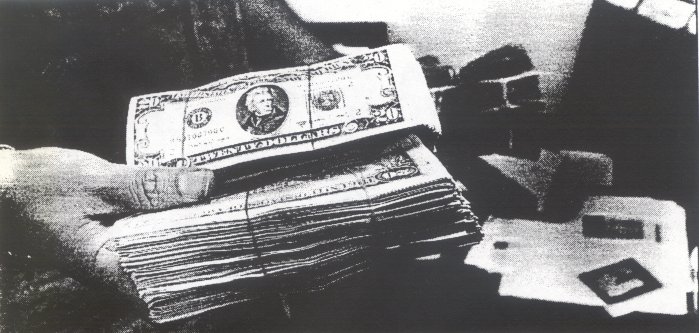

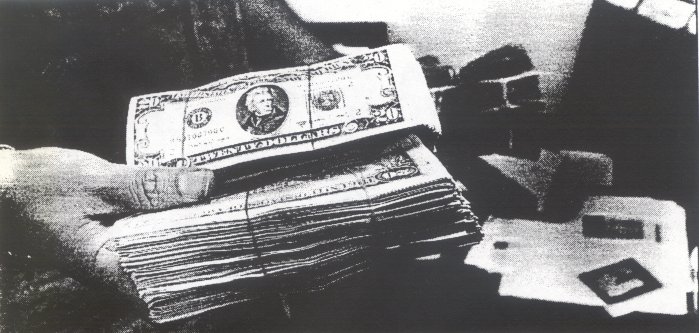

Airport drug team sieze cash from travelers suspected of being couriers

The Law: Guilt Doesn't Matter

Rooted in English common law, forfeiture has surfaced just twice in the United States since colonial times.

In 1862, Congress permitted the president to seize estates of Confederate soldiers. Then, in 1970, it resurrected forfeiture for the civil war on drugs with the passage of racketeering laws that targeted the assets of criminals.

In 1984 however, the nature of the law was radically changed to allow government to take possession without first charging, let alone convicting the owner. That was done in an effort to make it easier to strike at the heart of the major drug dealers. Cops knew that drug dealers consider prison time an inevitable cost of doing business. It rarely deters them. Profits and playthings, though, are their passions. Losing them hurts.

And there was a bonus in the law. the proceeds would flow back to law enforcement to finance more investigations. It was to be the ultimate poetic justice, with criminals financing their own undoing.

But eliminating the necessity of charging or proving a crime has moved most of the action to civil court, where the government accuses the item -- not the owner -- of being tainted by a crime.

This oddity has court dockets looking like purchase orders: United States of America vs. 9.6 acres of land and lake; U.S. vs. 667 bottles of wine. But it's more than just a labeling change. Because money and property are at stake instead of life and liberty, the constitutional safeguards in criminal proceedings do not apply.

The result is that "jury trials can be refused; illegal searches condoned; rules of evidence ignored," says Louisville, Ky. defense lawyer Donald Heavrin. The "frenzied quest for cash," he says, is "destroying the judicial system."

Every crime package passed since 1984 has expanded the uses of forfeiture, and now there are more than 100 statutes in place at the state and federal level. Not just for drug cases anymore, forfeiture covers the likes of money laundering, fraud, gambling, importing tainted meats and carrying intoxicants onto Indian land.

The White House, Justice Department and Drug Enforcement Administration say they've made the most of the expanded law in getting the big-time criminals, and they boast of seizing mansions, planes and millions in cash. But the Pittsburgh Press in just 10 months was able to document 510 current cases that involved innocent people -- or those possessing a very small amount of drugs -- who lost their possessions.

And DEA's own database contradicts the official line. It showed that big-ticket items -- valued at more than $50,000 -- were only 17 percent of the total 25,297 items seized by DEA during the 18 months that ended last December.

"If you want to use that 'war on drugs' analogy, the forfeiture is like giving the troops permission to loot," says Thomas Lorenzi, presidentelect of the Louisiana Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers.

The near-obsession with forfeiture continues without any proof that it curbs drug crime -- its original target.

"The reality is, it's very difficult to tell what the impact of drug seizure is," says Stanley Morris, deputy director of the federal drug czar's office.

Police Forces Keep the Take

The "loot" that's coming back to police forces all over the nation has redefined law-enforcement success. It now has a dollar sign in front of it.

For nearly eighteen months, undercover Arizona State Troopers worked as drug couriers driving nearly 13 tons of marijuana from the Mexican border to stash houses around Tucson. They hoped to catch the Mexican suppliers and distributors on the American side before the dope got on the streets.

But they overestimated their ability to control the distribution. Almost every ounce was sold the minute they dropped it at the houses.

Even though the troopers were responsible for tons of drugs getting loose in Tucson, the man who supervised the setup still believes it was worthwhile. It was "a success from a cost-benefit standpoint," says former assistant attorney-general John Davis. His reasoning: It netted 20 arrests and at least $3 million for the state forfeiture fund.

"That kind of thinking is what frightens me," says Steve Sherick, a Tucson attorney. "The government's thirst for dollars is overcoming any long-range view of what it is supposed to be doing, which is fighting crime."

George Terwilliger III, associate deputy attorney general in charge of the U.S. Justice Department's program emphasizes that forfeiture does fight crime, and "we're not at all apologetic about the fact that we do benefit (financially) from it."

In fact, Terwilliger wrote about how the forfeiture program financially benefits police departments in the 1991 Police Buyer's Guide of Police Chief Magazine.

Between 1986 and 1990, the U.S. Justice Department generated $1.5 billion from forfeiture and estimates that it will take in $500 million this year, five times the amount it collected in 1986.

District attorney's offices throughout Pennsylvania handled $4.5 million in forfeitures last year; Allegheny County (ED: Pgh is in Allegheny County) $218,000, and the city of Pittsburgh, $191,000 -- up from $9,000 four years ago.

Forfeiture pads the smallest towns coffers. In Lexana, Kan, a Kansas City suburb of 29,000, "we've got about $250,000 moving in court right now," says narcotic detective Don Crohn.

Despite the huge amounts flowing to police departments, there are few public accounting procedures. Police who get a cut of the federal forfeiture funds must sign a form saying merely they will use it for "law enforcement purposes."

To Philadelphia police that meant new air conditioning. In Warren County, N.J., it meant use of a forfeited yellow Corvette for the chief assistant prosecutor.

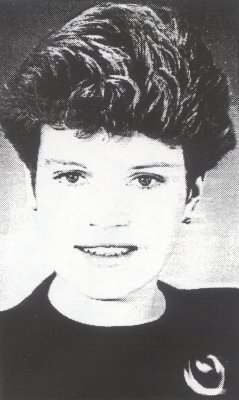

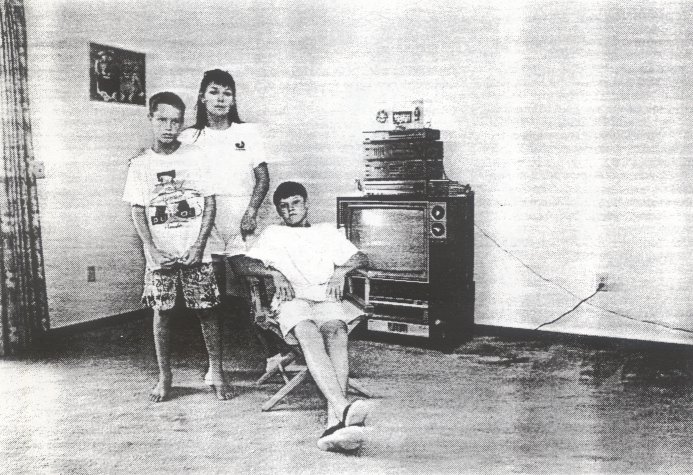

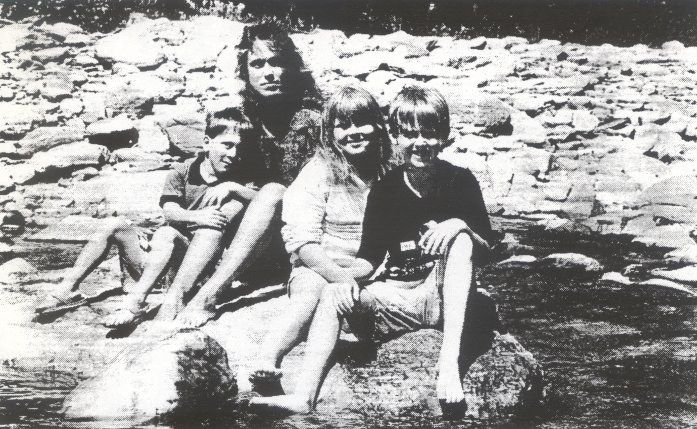

Judy Mulford, 31, and her 13-year old twins, Chris, left, and Jason, are down to essentials in their Lake Park, Fla., home, which the government took in 1989 after claiming her husband, Joseph, stored cocaine there. Neither parent has been criminally charged, but in April a forfeiture jury said Mrs. Mulford must forfeit the house she bought herself with an insurance settlement. The Mulfords have divorced, and she has sold most of her belongings to cover legal bills. She's asked for a new trial and lives in the near-empty house pending a decision.

'Looking' Like a Criminal

Ethel Hylton of New York City has yet to regain her financial independence after losing $39,110 in a search nearly three years ago in Hobby Airport in Houston.

Shortly after she arrived from New York, a Houston officer and Drug Enforcement Administration agent stopped the 46-year-old woman in the baggage area and told her she was under arrest because a drug dog had scratched at her luggage. The dog wasn't with them, and when Miss Hylton asked to see it, the officers refused to bring it out.

The agents searched her bags, and ordered a strip search of Miss Hylton, but found no contraband.

In her purse they found the cash Miss Hylton carried because she planned to buy a house to escape the New York winters which exacerbated her diabetes. It was the settlement from an insurance claim, and her life's savings, gathered through more than 20 years of work as a hotel housekeeper and hospital night janitor.

The police seized all but $10 of the cash and sent Miss Hylton on her way, keeping the money because of its alleged drug connection. But they never charged her with a crime.

The Pittsburgh Press verified her jobs, reviewed her bank statements and substantiated her claim she had $18,000 from an insurance settlement. It also found no criminal record for her in New York City.

With the mix of outrage and resignation voiced by other victims of searches, she says: "The money they took was mine. I'm allowed to have it. I earned it."

Miss Hylton became a U.S. citizen six years ago. She asks, "Why did they stop me? Is it because I'm black or because I'm Jamaican?"

Probably, both -- although Houston police haven't said.

Drug teams interviewed in dozens of airports, train stations and bus terminals and along other major highways repeatedly said they didn't stop travellers based on race. But a Pittsburgh Press examination of 121 travellers' cases in which police found no dope, made no arrest, but seized money anyway showed that 77 percent of the people stopped were black, Hispanic, or Asian.

In April, 1989, deputies from Jefferson Davis Parish, Louisiana, seized $23,000 from Johnny Sotello, a Mexican-American whose truck overheated on a highway.

They offered help, he accepted. They asked to search his truck. He agreed. They asked if he was carrying cash. He said he was because he was scouting heavy equipment auctions.

They then pulled a door panel from the truck, said the space behind it could have hidden drugs, and seized the money and the truck, court records show. Police did not arrest Sotello but told him he would have to go to court to recover his property.

Sotello sent auctioneer's receipts to police which showed he was a licensed buyer. the sheriff offered to settle the case, and with his legal bills mounting after two years, Sotello accepted. In a deal cut last March, he got his truck, but only half his money. The cops kept $11,500.

"I was more afraid of the banks than anything -- that's one reason I carry cash," says Sotello. "But a lot of places won't take checks, only cash, or cashier's checks for the exact amount. I never heard of anybody saying you couldn't carry cash."

Affidavits show the same deputy who stopped Sotello routinely stopped the cars or black and Hispanic drivers, exacting "donations" from some.

After another of the deputy's stops, two black men from Atlanta handed over $1,000 for a "drug fund" after being detained for hours, according to a hand-written receipt reviewed by the Pittsburgh Press.

The driver got a ticket for "following too close." Back home, they got a lawyer.

Their attorney, in a letter to the Sheriff's department, said deputies had made the men "fear for their safety, and in direct exploitation of that fear a purported donation of $1000 was extracted..."

If they "were kind enough to give the money to the sheriff's office," the letter said, "then you can be kind enough to give it back." If they gave the money "under other circumstances, then give the money back so we can avoid litigation."

Six days later, the sheriff's department mailed the men a $1,000 check.

Last year, the 72 deputies of Jefferson Davis Parish led the state in forfeitures, gathering $1 million -- more than their colleagues in New Orleans, a city 17 times larger than the parish.

Like most states, Louisiana returns the money to law enforcement agencies, but it has one of the more unusual distributions: 60 percent goes to the police bringing a case, 20 percent to the district attorney's office prosecuting it and 20 percent to the court fund of the judge signing the forfeiture order.

"The highway stops aren't much different from a smash-and-grab ring," says Lorenzi, of the Louisiana Defense Lawyers Association.

George Terwillger, who helps set justice Department's forfeiture policy, calls the law "effective."

Paying For Your Innocence

The Justice Department's Terwilliger says that in some cases "dumb judgement" may occasionally cause problems, but he believes there is an adequate solution. "That's why we have courts."

But the notion that courts are a safeguard for citizens wrongly accused "is way off," says Thomas Kerner, a forfeiture lawyer in Boston. "Compared to forfeiture, David and Goliath was a fair fight."

Starting from the moment that the government serves notice that it intends to take an item, until any court challenge is completed, "the government gets all the breaks," says Kerner.

The government need only show probable cause for a seizure, a standard no greater than what is needed to get a search warrant. The lower standard means the government can take a home without any more evidence than it normally needs to take a look inside.

Clients who challenge the government, says attorney Edward Hinson of Charlotte, N.C., "have the choice of fighting the full resources of the U.S. treasury or caving in."

Barry Kolin caved in.

Kolin watched Portland, Ore., police padlock the doors of Harvey's, his bar and restaurant for bookmaking on March 2.

Earlier that day, eight police officers and Amy Holmes Hehn, the Multnomah County deputy district attorney, had swept into the bar, shooed out waitresses and customers and arrested Mike Kolin, Barry's brother and bartender, on suspicion of bookmaking.

Nothing in the police documents mentioned Barry Kolin, and so the 40-year-old was stunned when authorities took his business, saying they believe he knew about the betting. He denied it.

Hehn concedes she did not have the evidence to press a criminal case against Barry Kolin, "so we seized the business civilly."

During a recess in a hearing on the seizures weeks later, "the deputy DA says if I paid them $30,000 I could open up again," Kolin recalls. When the deal dropped to $10,000, Kolin took it.

Kolin's lawyer, Jenny Cooke, calls the seizure "extortion." She says: "There is no difference between what the police did to Barry Kolin or what Al Capone did in Chicago when he walked in and said, 'This is a nice little bar and it's mine.' the only difference is today they call this civil forfeiture."

Minor Crimes, Major Penalties

Forfeiture's tremendous clout helps make it "one of the most effective tools that we have," says Terwilliger.

The clout, though, puts property owners at risk of losing more under forfeiture that they would in a criminal case under the same circumstances.

Criminal charges in federal and many state courts carry maximum sentences. But there's no dollar cap on forfeiture, leaving citizens open to punishment that far exceeds the crime.

Robert Brewer of Irwin, Idaho, is dying of prostate cancer, and uses marijuana to ease the pain and nausea that comes with radiation treatments.

Last Oct. 10, a dozen deputies and Idaho tax agents walked into the Brewer's living room with guns drawn and said they had a warrant to search.

The Brewers, Robert, 61, and Bonita, 44, both retired form the postal service, moved from Kansas City, Mo., to the tranquil, wooded valley of Irwin in 1989. Six months later, he was diagnosed.

According to police reports, an informant told authorities Brewer ran a major marijuana operation.

The drug SWAT team found eight plants in the basement under a grow light and a half-pound of marijuana. The Brewers were charged with two felony narcotics counts and two charges for failing to buy state tax stamps for the dope.

"I didn't like the idea of the marijuana, but it was the only thing that controlled his pain," Mrs. Brewer says.

The government seized the couples five-year-old Ford van that allowed him to lie down during his twice-a-month trips for cancer treatment at a Salt Lake City hospital, 270 miles away. Now they must go by car.

"That's a long painful ride for him ... He needed that van, and the government took it," Mrs. Brewer says. "It looks like they can punish people any way they see fit."

The Brewers know nothing about the informant who turned them in, but informants play a big role in forfeiture. Many of them are paid, targeting property in return for a cut of anything that is taken.

The Justice Department's asset forfeiture fund paid $24 mil. to informants in 1990 and has $22 million allocated this year.

Private citizens who snitch for a fee are everywhere. Some airline counter clerks receive cash awards for alerting drug agents to "suspicious" travellers. The practice netted Melissa Furtner, a Continental Airlines clerk in Denver, at least $5,800 between 1989 and 1990, photocopies of checks show.

Increased surveillance, recruitment of citizen-cops, and expansion of forfeiture sweeps are all part of a take-now, litigate-later syndrome that builds prosecutors careers, says a former federal prosecutor.

"Federal law enforcement people are the most ambitious I've ever met, and to get ahead they need visible results. Visible results are convictions, and, now, forfeitures," says Don Lewis of Meadville, Crawford County. (ED: a Pa county north of Pgh by two counties.)

Lewis spent 17 years as a prosecutor, serving as an assistant U.S. attorney in Tampa as recently as 1988. He left the Tampa Job -- and became a defense lawyer -- when "I found myself tempted to do things I wouldn't have thought about doing years ago."

Terwilliger insists U.S. attorneys would never be evaluated on "something as unprofessional as dollars."

Which is not to say Justice doesn't watch the bottom line.

Cary Copeland, director of the department' Executive Office for Asset Forfeiture, says they tried to "squeeze the pipeline" in 1990 when the amount forfeited lagged behind Justice's budget projections.

He said this was done by speeding up the process, not by doing a "whole lot of seizures."

Ending the Abuse

While defense lawyers talk of reforming the law, agencies that initiate forfeiture scarcely talk at all.

DEA headquarters makes a spectacle of busts like the seizure of fraternity houses at the University of Virginia in March. But it refuses to supply detailed information on the small cases that account for most of its activity.

Local prosecutors are just as tight-lipped. Thomas Corbett, U.S. Attorney for Western Pennsylvania, seals court documents on forfeitures because "there are just some things I don't want to publicize. the person whose assets we seize will eventually know, and who else has to?"

Although some investigations need to be protected, there is an "inappropriate secrecy" spreading throughout the country, says Jeffrey Weiner, president-elect of the 25,000 member National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers.

"The Justice Department boasts of the few big fish they catch. But they throw a cloak of secrecy over the information on how many innocent people are getting swept up in the same seizure net, so no one can see the enormity of the atrocity."

Terwilliger says the net catches the right people: "bad guys" as he calls them.

But a 1990 Justice report on drug task forces in 15 states found they stayed away from the in-depth financial investigations needed to cripple major traffickers. Instead, "they're going for the easy stuff," says James "Chip" Coldren, Jr., executive director of the Bureau of Justice Assistance, a research arm of the federal Justice Department.

Lawyers who say the law needs to be changed start with the basics: The government shouldn't be allowed to take property until after it proves the owner guilty of a crime.

But they go on to list other improvements, including having police abide by their state laws, which often don't give police as much latitude as the federal law. Now they can use federal courts to circumvent the state.

Tracy Thomas is caught in that very bind.

A jurisprudence version of the shell game hides roughly $13,000 taken from Thomas, a resident of Chester, near Philadelphia.

Thomas was visiting in his godson's home on Memorial Day, 1990, when local police entered looking for drugs allegedly sold by the godson. They found none and didn't file a criminal charge in the incident. But they seized $13,000 from Thomas, who works as a $70,000-a-year engineer, says his attorney, Clinton Johnson.

The cash was left over from a Sheriff's sale he'd attended a few days before, court records show. the sale required cash -- much like the government's own auctions.

During a hearing over the seized money, Thomas presented a withdrawal slip showing he'd removed money from his credit union shortly before the trip and a receipt showing how much he had paid for the property he'd bought at the sale. The balance was $13,000.

On June 22, 1990, a state judge ordered Chester police to return Thomas' cash.

They haven't.

Just before the court order was issued, the police turned over the cash to the DEA for processing as a federal case, forcing Thomas to fight another level of government. Thomas is now suing the Chester police, the arresting officer, and the DEA.

"When DEA took over that money, what they in effect told a local police department is that it's OK to break the law," says Clinton Johnson, attorney for Thomas.

Police manipulate the courts not only to make it harder on owners to recover property, but to make it easier for police to get a hefty share of any forfeited goods. In federal court, local police are guaranteed up to 80 percent of the take -- a percentage that may be more than they'd receive under state law.

Pennsylvania's leading police agency-- the state police -- and the state's lead prosecutor -- the Attorney General -- bickered for two years over state police taking cases to federal court, an arrangement that cut the Attorney General out of the sharing.

The two state agencies now have a written agreement on how to divvy the take.

The same debate is heard around the nation.

The hallways outside Cleveland courtrooms ring with arguments over who will get what, says Jay Milano, a Cleveland criminal defense attorney.

"It's causing a feeding frenzy."

GOVERNMENT SEIZED HOME OF MAN WHO WAS GOING BLIND

James Burton says he loves America and wants to come home. But he can't. If he does, he'll wind up in prison, go blind, or both. Burton and his wife, Linda, live in an austere, concrete-slab apartment furnished with lawn chairs near Rotterdam in the Netherlands. It is home much different from the large house and 90-acre farm they owned near Bowling Green, Ky., before the government seized both.

For Burton, who has glaucoma, home-grown marijuana provided his relief - and his undoing.

Since 1972, federal health secretaries have reported to Congress that marijuana is beneficial in the treatment of glaucoma and several other medical conditions.

Yet while some officials within the Drug Enforcement Administration have acknowledged that medical value of marijuana, drug agents continue to seize property where chronically ill people grow it.

"Because of the emotional rhetoric connected with the marijuana issue, a doctor who can prescribe cocaine, morphine, amphetamines, and barbiturates cannot prescribe marijuana, which is the safest therapeutically active drug known to man," Francis Young, administrative law judge for DEA, was quoted as saying in Burton's trial.

In an interview this past July 4, Burton said, "We don't really have any choice right now but to stay" in the Netherlands, where they moved after he completed a one-year jail term for three counts of marijuana possession. "I can buy or grow marijuana here legally, and if I don't have the marijuana, I'll go blind.

Burton, a 43-year-old Vietnam War veteran, has a rare form of hereditary, low-tension glaucoma. All of the men on his mother's side of the family have the disease, and several already are blind. It does not respond to traditional medications.

At the time of Burton's arrest, N.C. ophthalmologist Dr. John Merritt was the only physician authorized by he government to test marijuana in the treatment of glaucoma patients. Merritt testified at Burton's trial that marijuana was "the only medication' that could keep him from going blind.

On July 7, 1987 Kentucky state police raided Burton's farm and found 138 marijuana plants and two pounds of raw marijuana. "It was the kickoff of Kentucky drug awareness month, and I was their special kickoff feature. It was all over television," Burton said.

Burton admitted growing enough marijuana to produce about a pound a month for the 10 to 15 cigarettes he uses each day to reduce pressure in his eye.

A jury decided he grew the dope for his own use - not to sell, as the government contended - and in March 1988 found him guilty of three counts of simple possession.

The pre-sentence report on Burton shows he had no previous arrests. The judge sentenced him to a year in a federal maximum security prison, with no parole.

On top of that, the government took his farm: 90 rolling, wooded acres in Warren Country purchased for $34,701 in 1980 and assessed at twice that amount when it was taken.

On March 27, 1989, U.S. District Judge Ronald Meredith - without hearing any witnesses and without allowing Burton to testify in his own behalf - ordered the farm forfeited and gave the Burtons 10 days to get off the land. When owners of property live at a site while marijuana is growing in their presence, there is no defense to forfeiture," Meredith ruled.

"I never got to say two words in defense of keeping my home, something we worked and saved for for 18 years," said Burton, who was a master electrical technician. Linda, 41, worked for an insurance company. "On a serious matter like taking a person's home, you'd think the government would give you a chance to defend it."

Joe Whittle, the U.S. Attorney who prosecuted the Burton case, says he didn't know about the glaucoma until Burton's lawyer raised the issue in court. His office has "taken a lot of heat on this case and what happened to that poor guy," Whittle says. "But we did nothing improper."

"Congress passed these laws, and we have to follow them. If the American people wanted to exempt certain marijuana activity - these mom and pop or personal use or medical cases - they should speak through their duly elected officials and change the laws. Until those laws are changed, we must enforce them to the full extent of our resources."

The action was "an unequaled and outrageous example of government abuse," says Louisville lawyer Donald Heavrin, who failed to get the U.S. Supreme Court to hear the case.

"To send a man trying to save his vision to prison, and steal the home and land that he and his wife had worked decades for, should have the authors of the Constitution spinning in their graves."

Part Two: THE WAY YOU LOOK

Drug agents more likely to stop minorities

by Andrew Schneider and Mary Pat Flaherty

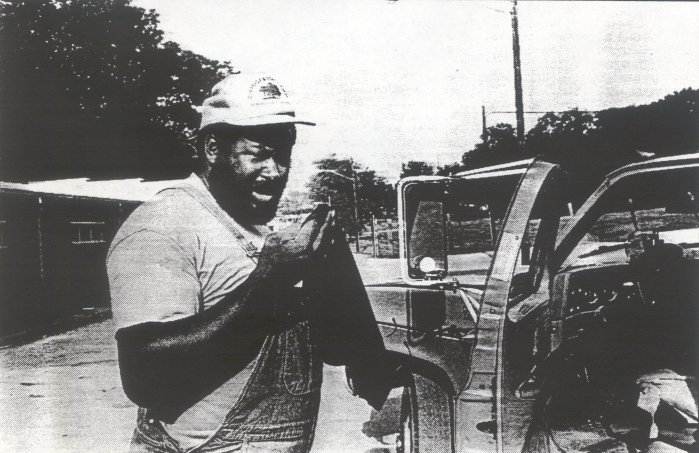

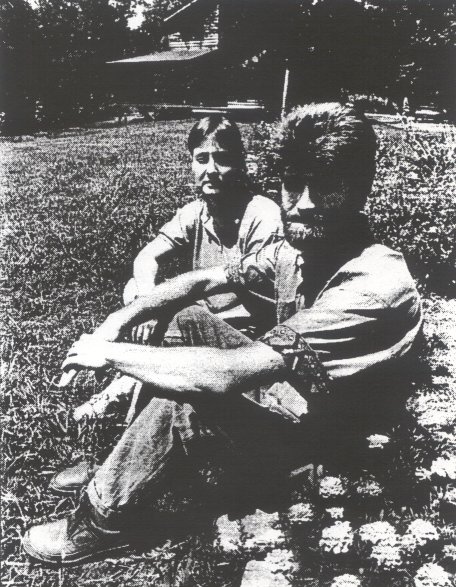

Willie Jones had $9.600 seized and is now fighting to keep his landscaping business

Look around carefully the next time you're at any of the nation's big airports, bus stations, train terminals or on a major highway, because there may be a government agent watching you. If you're black, Hispanic, Asian or look like a "hippie, " you can almost count on it.

The men and women doing the spying are drug agents, the frontline troops in the government's war on narcotics. They count their victories in the number of people they stop because they suspect they're carrying drugs or drug money.

But each year in the hunt for suspects, thousands of guiltless citizens are stopped, most often because of their skin color.

A 10-month Pittsburgh Press investigation of drug seizure and forfeiture included an examination of court records on 121 "drug courier" stops where money was seized and no drugs were discovered. The Pittsburgh Press found that black, Hispanic and Asian people account for 77 percent of the cases.

In making stops, drug agents use a profile, a set of speculative behavioral traits that gauge the suspect's appearance, demeanor and willingness to look a police officer in the eye.

For years, the drug courier profile counted race as a principal indicator of the likelihood of a person's carrying drugs.

But today the word "profile" isn't officially mentioned by police. Seeing the word scrawled in a police report or hearing if from a witness chair instantly unnerves prosecutors and makes defense lawyers giddy. Both sides know the racial implications can raise constitutional challenges.

Even so, far away from the courtrooms, the practice persists.

In Memphis, Tenn, in 1989, drug officers have testified, about 75 percent of the people they stopped in the airport were black.

In Eagle Country, Colo., the 60 mile-long strip of Interstate 70 that winds and dips past Vail and other ski areas is the setting of a class action suit that charges race was the main element of the profile used in drug stops.

According to court documents in one of the cases that led to the suit, the sheriff and two deputies testified that "being black or Hispanic was and is a factor" in their drug courier profiles.

Lawyer David Lane says that 500 people - primarily Hispanic and black motorists - were stopped and searched by Eagle County's High Country Drug Task Force during 1989 and 1990. Each time Lane charged, the task force used an unconstitutional profile based on race, ethnicity and out-of-state license plates.

Byron Boudreaux was one of those stopped.

Boudreaux was driving from Oklahoma to a new job in Canada when Sgt. James Perry and three other task force officers pulled him over.

"Sgt. Perry told me that I was stopped because my car fit the description of someone trafficking drugs in the area," Boudreaux says. He let the officers search his car.

"Listen, I was a black man traveling alone up in the mountains of Eagle County and surrounded by four police officers. I was going to be as cooperative as I could," he recalls.

For almost an hour the officers unloaded and searched the suitcases, laundry baskets and boxes that were wedged into Boudreaux's car. Nothing was found.

"I was stopped because I was black, and that's not a great testament to our law enforcement system," says Boudreaux, who is now an assistant basketball coach at Queens College in Charlotte, N.C.

In a federal trial stemming from another stop Perry made on the same road a few months later, he testified that because of "astigmatism and color blindness" he was unable to distinguish among black, Hispanic and white people.

U.S. District Court Judge Jim Carrigan didn't buy it and called the sergeant's testimony "incredible".

"If this nation were to win its war on drugs at the cost of sacrificing its citizens' constitutional rights, it would be a Pyrrhic victory indeed," Carrigan wrote in a court opinion. "If the rule of law rather than the rule of man is to prevail, there cannot be one set of search and seizure rules applicable to some and a different set applicable to others."

LIVELIHOOD IN JEOPARDY

In Nashville, Tenn, Willie Jones has no doubt that police still use a profile based on race.

Jones, owner of a landscaping service, thought the ticket agent at the American Arilines counter in Nashville Metro Airport reacted strangely when he paid cash Feb. 27 for his round-trip ticket to Houston.

"She said no one ever paid in cash anymore and she'd have to go in the back and check on what to do," Jones says.

What Jones didn't know is that in Nashville - as in other airports - many airport employees double as paid informers for the police.

The Drug Enforcement Administration usually pays them 10 percent of any money seized, says Capt. Judy Bawcum, head of the Nashville police division that runs the airport unit.

Jones got his ticket. Ten minutes later, as he waited for his plane, two drug team members stopped him.

"They flashed their badges and asked if I was carrying drugs or a large amount of money. I told them I didn't have anything to do with drugs, but I had money on me to to buy some plants for my business," Jones says.

They searched his overnight bag and found nothing. They patted him down and felt a bulge. Jones pulled out a black plastic wallet hidden under his shirt. It held $9,600.

"I explained that I was going to Houston to order some shrubbery for my nursery. I do it twice a year and pay cash because that's the way the growers want it," says the father of three girls.

The drug agents took his money.

"They said I was going to buy drugs with it, that their dog sniffed it and said it had drugs on it," Jones says. He never saw a dog.

The officers didn't arrest Jones, but they kept the money. They gave him a DEA receipt for the cash. But under the heading of amount and description, Sgt. Claude Byrum wrote, "Unspecified amount of U.S. Currency."

Jones says losing the money almost put him out of business.

"That was to buy my stock, I'm known for having a good selection of unusual plants. That's why I go South twice a year to buy them. Now I've got to do it piecemeal, run out after I'm paid for a job and buy plants for the next one," he says.

Jones has receipts for three years showing that each fall and spring he buys plants from nurseries in other states.

"I just don't understand the government. I don't smoke. I don't drink. I don't wear gold chains and jewelry, and I don't get into trouble with the police," he says. "I didn't know it was against the law for a 42 year-old black man to have money in his pocket."

Tennessee police records confirm that the only charge ever filed against Jones was for drag racing 15 years ago.

"DEA says I have to pay $900, 10 percent of the money they took from me, just to have the right to try to get it back," Jones says.

His lawyer, E.E. "Bo" Edwards filled out government forms documenting that his client couldn't afford the $900 bond.

"If I'm going to feed my children, I need my truck, and the only way I can get that $900 is to sell it," Jones says.

It's been more than five months, and the only thing Jones has received from DEA are letters saying that his application to proceed with out paying the $900 bond was deficient. "But they never told us what those deficiencies were," says Edwards.

Jones is nearly resigned to losing the money. "I don't think I'll ever get it back. But I think the only reason they thought I was a drug dealer was because I'm black, and that bothers me."

It also bothers his lawyer.

"Of course he was stopped because he was black. No cop in his right mind would try that with a white businessman. These seizure laws give law enforcement a license to hunt, and the target of choice for many cops is those they believe are least capable of protecting themselves: blacks, Hispanics and poor whites," Edwards says.

MONEY STILL HELD

In Buffalo, N.Y., on Oct. 9, Juana Lopez, a dark-skinned Dominican had just gotten off a bus from New York City when she was stopped in the terminal by drug agents who wanted to search her luggage.

They found no drugs, but DEA Agent Bruce Johnson found $4,750 in cash wrapped with rubber bands in her purse. The money, the 28 year-old woman said, was to pay legal fees or bail for her common law husband. After he began questioning her, Johnson realized that he had arrested the husband for drugs two months earlier in the same bus station.

Johnson called the office of attorney Mark Mahoney, where Ms. Lopez said she was heading, and verified her appointment.

Johnson then told the woman she was free to go, but her money would stay with him because a drug dog had reacted to it.

Ms. Lopez has receipts showing the money was obtained legally - a third of it was borrowed, another third came from the sale of jewelry that belonged to her and her husband, and the rest from her savings as a hair stylist in the Bronx.

It has been more than nine months since the money was taken, and Assistant U.S. Attorney Richard Kaufman says the investigation is continuing.

Robert Clark, a Mobile, Ala., lawyer who has defended many travelers, says profile stops are the new form of racism.

"In the South in the '30s, we used to hang black folks. Now, given any excuse at all, even legal money in their pockets, we just seize them to death," he says.

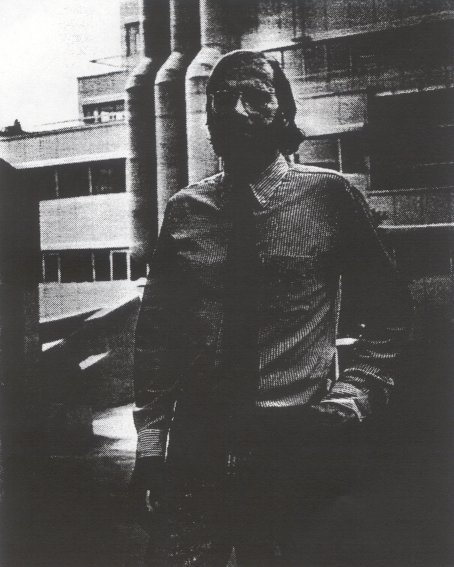

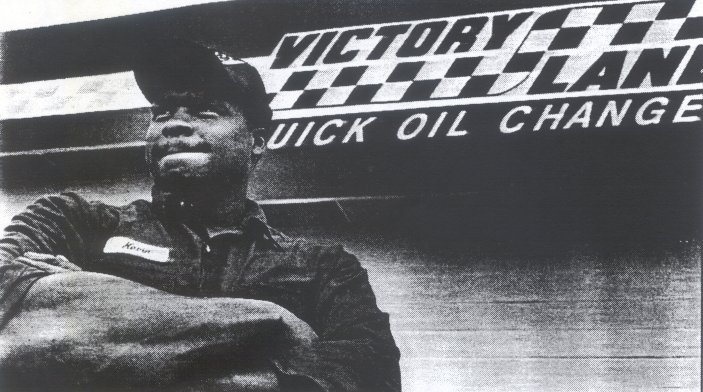

Former New York Giants center Kevin Belcher is one of hundreds whose cash was seized at airports

TRIVIAL PURSUIT

"If you took all the racial elements out of profiles, you'd be left with nothing," Says Nashville lawyer Edwards, who heads a new National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers task force to investigate forfeiture law abuses.

"It would outrage the public to learn the trivial indicators that police officers use as the basis for interfering with the rights of the innocent."

Examination of more than 310 affidavits for seizure and profiles used by 28 different agencies reveals a conflicting collection of traits that agents say they use to hunt down traffickers.

Guidelines for DEA drug task force agents in three adjacent states give conflicting advice on when officers are supposed to become suspicious.

Agents in Illinois are told it's suspicious if their subjects are among the first people off a plane, because it shows they're in a hurry.

In Michigan, the DEA says that being the last off the plane is suspicious because the suspect is trying to appear unconcerned.

And in Ohio, agents are told suspicion should surface when suspects deplane in the middle of a group because they may be trying to lose themselves in the crowd.

One of the most often mentioned indicators is that suspects were traveling to or from a source city for drugs.

But a list of cities favored by drug couriers gleaned from the DEA affidavits amounts to a compendium of every major community in the United States.

Seeming to be nervous, looking around, pacing, looking at a watch, making a phone call - all things that business travelers routinely do, especially those who are late or don't like to fly - sound alarms to waiting drug agents.

Some agents change their mind about what makes them suspicious.

In Tennessee, an agent told a judge he was leery of a man because he "walked quickly through the airport." Six weeks later, in another affidavit, the same agent said his suspicions were aroused because the suspect "walked with intentional slowness after getting off the bus."

In Albuquerque, N.M., people have been stopped because they were standing on the train platform watching people.

Whether you look at a police officer can be construed to be a suspicious sign. One Maryland state trooper said he was wary because the subject deliberately did not look at me when he drove by my position." Yet, another Maryland trooper testified that he stopped a man because the "driver stared at me when he passed."

Too much baggage or not enough will draw the attention of the law.

You could be in trouble with drug agents if you're sitting in first class and don't look as if you belong there.

DEA Agent Paul Markonni, who is considered the "father" of the drug courier profile, testified in a Florida court about why he stopped a man.

"We do see some real slimeballs you know, some real dirt bags, that obviously could not afford, unless they were doing something, to fly first class," he told the court.

The newest extension of the drug courier profile are pagers and cellular telephones.

Based on the few cases that have reached the courts, the communication devices - which are carried by business people, nervous parents and patients waiting for a transplant as well as drug couriers - are primarily suspicious when they are found on the belts or in the suitcases of minorities or long haired whites.

For police intent on stopping someone, any reason will do.

"If they're black, Hispanic, Asian or look like a hippie, that's a stereo type, and the police will find some way to stop them if that's their intent," says San Antonio lawyer Gerald Goldstein.

THE PERFECT PROFILE

A DEA agent thought that former New York Giants center Kevin Belcher matched his profile. When Belcher got off a flight from Detroit March 2, he was stopped by DEA's Dallas/Fort Worth Airport Narcotics Task Force.

The Texas officers had been called a short while earlier by a DEA agent at Detroit's Metro Airport. A security screener had spotted a big, black man carrying a large amount of money in his jacked pocket, the Detroit agent reported to his Southern colleagues.

Belcher was questioned about the purpose of the trip and was asked whether he had any money. He gave the agents $18,265.

Belcher explained that he was going to El Paso to buy some classic old cars - "1968 or '69 Camaros are what I'm looking for." Belcher, whose professional football career ended after a near-fatal traffic accident in New Jersey, told the agents he owned four Victory Lane Quick Oil Change outlets in Michigan. The money came from sales, he said, and cash was what auctioneers demanded.

A drug-sniffing dog was called, it reacted, and the money was seized.

Agent Rick Watson told Belcher he was free to go "but that I was going to detain the monies to determine the origin of them."

In his seizure affidavit, Watson listed the matches he made between Belcher and the profile of "other narcotic currency couriers encountered at DFW airport.

Included in Watson's profile was that Belcher had bought a one way ticket on the date of travel; was traveling to a "source" city, El Paso, "where drug dealers have long been known to be exporting large amounts of marijuana to other parts of the country"; and was carrying $100, $50, $20, $10 and $5 bills, "which is consistent with drug asset seizures."

Watson made no mention as to what denomination other than $1 bills was left for non-drug traffickers to carry.

"The drug courier profile can be absolutely anything that the police officer decides it is at that moment," says Albuquerque defense lawyer Nancy Hollander, one of the nation's leading authorities on profile stops.

WIDE NET CAST

Officials are reluctant to reveal how many innocent people are ensnared each day by profile stops. Most police departments say they don't keep that information. Those that do are reluctant to discuss it.

"We don't like to talk much about what we seize at the (Nashville) airport because it might stir up the public and make the airport officials unhappy because we are somehow harassing people. It would be great if we could keep the whole operation secret," says Capt. Bawcum, in charge of the airport's drug team.

Capt. Rudy Sandoval, commander of Denver's vice bureau, says he doesn't keep the airport numbers but estimates his police searched more than 2,000 people in 1990, but arrested only 49 and seized money from fewer than 50.

At Pittsburgh's airport, numbers are kept. The team searched 527 people last year, and arrested 49.

A federal court judge in Buffalo, N.Y., says police stop too many innocent people to catch too few crooks.

Judge George Pratt said he was shocked that police charged only 10 of the 600 people stopped in 1989 in the Buffalo airport and decried encroaching on the constitutional rights of the 590 innocent people.

In his opinion in the case, Pratt said that by conducting unreasonable searches: "It appears that they have sacrificed the Fourth Amendment by detaining 590 innocent people in order to arrest 10 - who are not - all in the name of the 'war on drugs.' When, pray tell, will it end ? Where are we going?"

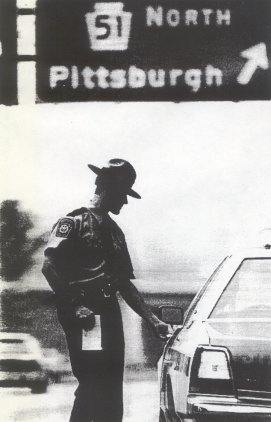

U.S. Customs agent Leon Senecal and drug dog Amber check a bus in Buffalo

DRUGS CONTAMINATE NEARLY ALL THE MONEY IN AMERICA

Police seize money from thousands of people each year because a dog with a badge sniffs, barks or paws to show that bills are tainted with drugs.

If a police officer picks you out as a likely drug courier, the dog is used to confirm that your money has the smell of drugs.

But scientists say the test the police rely on is no test at all because drugs contaminate virtually all the currency in America.

Over a seven-year period, Dr. Jay Poupko and his colleagues at Toxicology Consultants Inc. in Miami have repeatedly tested currency in Austin, Dallas, Los Angeles, Memphis, Miami, Milwaukee, New Youk City, Pittsburgh, Seattle and Syracuse. He also tested American bills in London.

"An average of 96 percent of all the bills we analyzed from the 11 cities tested positive for cocaine. I don't think any rational thinking person can dispute that almost all the currency in this country is tainted with drugs," Poupko says.

Scientists at national Medical Services, in Willow Grove, Pa., who tested money from banks and other legal sources more than a dozen times, consistently found cocaine on more than 80 percent of the bills.

"Cocaine is very adhesive and easily transferable," says Vincent Cordova, director of criminalistic for the private lab. "A police officer, pharmacist, toxicologist or anyone else who handles cocaine, including drug traffickers, can shake hands with someone, who eventually touches money, and the contamination process begins."

Cordova and other scientists use gas chromatography and mass spectroscopy, precise alcohol washes and a dozen other sophisticated techniques to identify the presence of narcotics down to the nanogram level - one billionth of a gram. That measure, which is far less than a pin point, is the same level a dog can detect with a sniff.

What a drug dog cannot do, which the scientists can, is quantify the amount of drugs on the bills.

Half of the money Cordova examined had levels of cocaine at or above 9 nanograms. This level means the bills were either near a source of cocaine or were handled by someone who touched the drug, he says.

Another 30 percent of the bills he examined show levels below 9 nanograms, which indicated "the bills were probably in a cash drawer, wallet or some place where they came in contact with money previously contaminated."

The lab's research found $20 bills are most highly contaminated, with $10 and $5 bills next. The $1, $50 and $100 bill usually have the lowest cocaine levels.

Cordova urges restraint in linking possession of contaminated money to a criminal act.

"Police and prosecutors have got to use caution in how far they go. The presence of cocaine on bills cannot be used as valid proof that the holder of the money, or the bills themselves, have ever been in direct contact with drugs," says Cordova, who spent 11 years directing the Philadelphia Police crime laboratory.

Nevertheless, more and more drug dogs are being put to work.

Some agencies, like the U.S. Customs Service, are using passive dogs that don't rip into an item - or person - when the dogs find something during a search. These dogs just sit and wag their tails. German shepherds with names like Killer and Rambo are being replaced by Labradors named Bruce or Memphis "chocolate Mousse."

Marijuana presents its own problems for dogs since its very pungent smell is long-lasting. Trainers have testified that drug dogs can react to clothing containers or cars months after marijuana has been removed.

A 1989 case in Richmond, Va., addressed the issue of how reliable dogs are in marijuana searches.

Jack Adams, a special agent with the Virginia State Police, supervised training of drug dogs for the state.

He said the odor from a single suitcase filled with marijuana and placed with 100 other bags in a closed Amtrak baggage car in Miami could permeate all the other bags in the car by the time the train reached Richmond.

And what happens to the mountain of "drug-contaminated" dollars the government seized each year ? The bills aren't burned, cleaned, or stored in a well-guarded warehouse.

Twenty-one seizing agencies questioned all said that tainted money was deposited in a local bank - which means it's back in circulation.

Part Three: INNOCENT OWNERS

Police profit by seizing homes of innocent

by Andrew Schneider and Mary Pat Flaherty

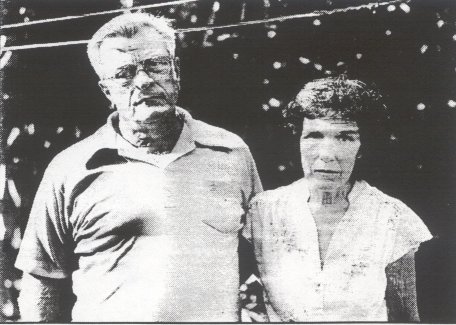

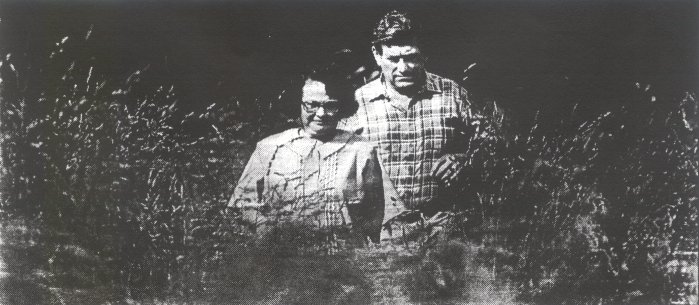

Four years after their son's marijuana arrest, police seized Hawaii home of Joseph and Frances Lopes

The second time police came to the Hawaii home of Joseph and Frances Lopes, they came to take it.

"They were in a car and a van, I was in the garage. They said, 'Mrs. Lopes, let's go into the house, and we will explain things to you.' They sat in the dining room and told me they were taking the house. It made my heart beat very fast."

For the rest of the day, 60-year old Frances Lopes and her 65-year-old husband, Joseph, trailed federal agents as they walked through every room of the Maui house, the agents recording the position of each piece of furniture on a video tape that serves as the government's inventory.

Four years after their mentally unstable adult son pleaded guilty to growing marijuana in their back yard for his own use, the Lopeses face the loss of their home. A Maui detective trolling for missed forfeiture opportunities spotted the old case. He recognized that the law allowed him to take away their property because they knew their son had committed a crime on it.

A forfeiture law intended to strip drug traffickers of ill-gotten gains often is turned on people, like the Lopeses, who have not committed a crime. The incentive for the police to do that is financial, since the federal government and most states let the police departments keep the proceeds from what they take.

The law tries to temper money making temptations with protections for innocent owners, including lien holders, landlords whose tenants misuse property, or people unaware of their spouse's misdeeds. The protection is supposed to cover anyone with an interest in a property who can prove he did not know about the alleged illegal activity, did not consent to it, or took all reasonable steps to prevent it.

But a Pittsburgh Press investigation found that those supposed safeguards do not come into play until after the government takes an asset, forcing innocent owners to hire attorneys to get their property back - if they ever do.

"As if the law weren't bad enough they just clobber you financially," says Wayne Davis, an attorney from Little Rock, Ark.

FEARED FOR THEIR SON

In 1987, Thomas Lopes, who was then 28 and living in his parents' home, pleaded guilty to growing marijuana in their back yard. Officers spotted it from a helicopter.

Because it was his first offense, Thomas received probation and an order to see a psychologist. From the time he was young, mental problems tormented Thomas, and though he visited a psychologist as a teen , he had refused to continue as he grew older, his parents say.

Instead, he cloistered himself in his bedroom, leaving only to tend the garden.

His parents concede they knew he grew the marijuana.

"We did ask him to stop, and he would say, 'Don't touch it', or he would do something to himself," says the elder Lopes, who worked for 49 years on a sugar plantation and lived in its rented camp housing for 30 years while he saved to buy his own home.

Given Thomas' history and a family history of mental problems that caused a grandparent and an uncle to be committed to institutions, the threats stymied his parents.

The Lopeses, says their attorney Matthew Menzer, "were under duress. Everyone who has been diagnosed in this family ended up being taken away. They could not conceive of any way to get rid of the dope without getting rid of their son or losing him forever."

When police arrived to arrest Thomas, "I was so happy because I knew he would get care," says his mother. He did, and he continues weekly doctor's visits. His mood is better, Mrs. Lopes says, and he has never again grown marijuana or been arrested.

But his guilty plea haunts his family.

Because his parents admitted they knew what he was doing, their home was vulnerable to forfeiture.

Back when Thomas was arrested, police rarely took homes. But since, agencies have learned how to use the law and have seen the financial payoff, says Assistant U.S. Attorney Marshall Silverberg of Honolulu.

They also carefully review old cases for overlooked forfeiture possibilities, he says. The detective who uncovered the Lopes case started a forfeiture action in February - just under the five-year deadline for staking such a claim.

"I concede the time lapse on this case is longer than most, but there was a violation of the law, and that makes this appropriate, not money-grubbing," says Silverberg. "The other way to look at this, you know, is that the Lopeses could be happy we let them live there as long as we did." They don't see it that way.

Neither does their attorney, who says his firm now has about eight similar forfeiture cases, all of them stemming from small-time crimes that occurred years ago but were resurrected. "Digging these cases out now is a business proposition, not law enforcement," Menzer says.

"We thought it was all behind us," says Lopes. Now, "there isn't a day I don't think about what will happen to us."

They remain in the house, paying taxes and the mortgage, until the forfeiture case is resolved. Given court backlogs, that likely won't be until the middle of next year, Menzer says.

They've been warned to leave everything as it was when the videotape was shot.

"When they were going out the door," Mrs. Lopes says of the police, "they told me to take good care of the yard. They said they would be coming back one day."

'DUMB JUDGMENT'

Protections for innocent owners are "a neglected issue in federal and state forfeiture law," concluded the Police Executive Research Forum in its March bulletin.

But a chief policy maker on forfeiture maintains that the system is actively interested in protecting the rights of the innocent.

George J. Terwilliger III, associate deputy attorney general in the Justice Department, admits that there may be instances of "dumb judgment." And says if there's a "systemic" problem, he'd like to know about it.

But attorneys who battle forfeiture cases say dumb judgment is the systemic problem. And they point to some of Terwilliger's own decisions as examples.

The forfeiture policy that Terwilliger crafts in the nation's capital he puts on use in his other federal job: U.S. attorney for Vermont.

A coalition of Vermont residents, outraged by Terwilliger's forfeitures of homes in which small children live, launched a grass roots movement called "Stop Forfeiture of Children's Homes." Three months old, the group has about 70 members, from school principals to local medical societies.

Forfeitures are a particularly sensitive issue in Vermont where state law forbids taking a person's primary home. That restriction appears nowhere in federal law, which means Vermont police departments can circumvent the state constraint by taking forfeiture cases through federal courts.

The playmaker for that end-run: Terwilliger.

"It's government-sponsored child abuse that's destroying the future of children all over this state in the name of fighting the drug war," says Dr. Kathleen DePierro, a family practitioner who works at Vermont State hospital, a psychiatric facility in Waterbury.

The children of Karen and Reggie Lavalle, ages 6, 9 and 11, are precisely the type of victims over which the Vermonters agonize. Reggie Lavalle is serving a 10-year sentence in a federal prison in Minnesota for cocaine possession.

Because police said he had been involved with drug trafficking, his conviction cost his family their ranch house on 2 acres in a small village 20 miles east of Burlington. For the first time, the family is on welfare, in a rented duplex.

"I don't condone what my husband did, but why victimize my children because of his actions ? That house wasn't much, but it was ours. It was a home for the children, with rabbits, chicken, turkeys and a vegetable garden. Their friends were there, and they liked the school," says Mrs. Lavalle, 29.

After the eviction, "every night for months, Amber cried because she couldn't see her friends. I'd like to see the government tell this 9-year-old that this isn't cruel and unusual punishment."

Terwilliger's dual role particularly troubles DePierro. "It's horrifying to know he is setting policy that could expand this type of terror and abuse to kids in every state in the nation."

Terwilliger calls the group's allegations absurd. "If there was some one to blame, it would be the parents and not the government."

Lawyers like John MacFadyen, a defense attorney in Providence, R.I., find it harder to fix blame.

"The flaw with the innocent owner thing is that life doesn't paint itself in black and white. It's often times gray, and there is no room for gray in these laws," MacFadyen says. As a consequence, prosecutors presume everyone guilty and leave it to them to show otherwise. "That's not good judgment. In fact, it defies common sense."

PROVING INNOCENCE

Innocent owners who defend their interests expose themselves to questioning that bores deep into their private affairs. Because the forfeiture law is civil, they also have no protection against self-incrimination, which means that they risk having anything they say used against them later.

The documentation required of innocent owner Loretta Stearns illustrates how deeply the government plumbs.

The Connecticut woman lent her adult son $40,000 in 1988 to buy a home in Tequesta, Fla, court documents show.

Unlike many parents who treat such transactions informally, she had the foresight to record the loan as a mortgage with Palm Beach County. Her action ultimately protected her interest in the house after the federal government seized it, claiming her son stored cocaine there. He has not been charged criminally.

The seizure occurred in November 1989, and it took until last May before Mrs. Stearns convinced the government she had a legitimate interest in the house.

To prove herself an innocent owner, Mrs. Stearns met 14 requests for information, including providing "all documents of any kind whatsoever pertaining to your mortgage, including but not limited to loan application, credit reports, record of mortgages and mortgage payments, title reports, appraisal reports, closing documents, records of any liens, attachments on the defendant property, records of payments, canceled checks, internal correspondence or notes (hand-written or typed) relating to any of the above and opinion letter from borrower's or lender's counsel relating to any of the above."

And that was just question No. 1.

Karen Lavalee and her 3 children are the type of forfeiture victims that concern a Vermont group trying to stop government seizure of homes of children whose parents face drug charges

LANDLORD AS COP

Innocent owners are supposed to be shielded in forfeitures, but at times they've been expected to become virtual cops in order to protect their property from seizure.

T.T. Masonry Inc. owns a 36-unit apartment building in Milwaukee, Wis., that's plagued by dope dealing. Between January 1990, when it bought the building, and July 1990, when the city formally warned it about problems, the landlord evicted 10 tenants suspected of drug use, gave a master key to local beat and vice cops, forwarded tips to police and hired two security firms - including an off-duty city police officer - to patrol the building.

Despite that effort, the city sized the property. Assistant City Attorney David Stanosz says, "once a property develops a reputation as a place to buy drugs, the only way to fix that is to leave it totally vacant for a number of months. This landlord doesn't want to do that."

Correct, says Jermome Buting, attorney for Tom Torp of Masonry. "If this building is such a target for dealers, use that fact," says Buting. "Let undercover people go in. But when I raised that, the answer was they were short of officers and resources."

IT LOOKS LIKE COKE

Grady McClendon, 53, his wife, tow of their adult children and two grandchildren - 7 and 8 - were in a rented car headed to their Florida home in August 1989. They were returning from a family reunion in Dublin, Ga.

In Fitzgerald, Ga, McClendon made a wrong turn on a one-way street. Local police stopped him, checked his identification and asked permission to serach the car. He agreed.

Within minutes, police pulled open suitcases and purses, emptying out jewelry and about 10 Florida state lottery tickets. They also found a registered handgun.

Then says McClendon, the police "started waving a little stick they said was cocaine. They told me to put on my glasses and take a good look. I told them I'd never seen cocaine for real but that it didn't look like TV."

For about six hours, police detained the McClendon family at the police station where officers seized $2,300 in cash and other items, as "instruments of drug activity and gambling paraphernalia" - a reference to the lottery tickets.

Finally, they gave McClendon a traffic ticket and released them, but kept the family's possessions.

For 11 months, McClendon's attorney argued with the state, finally forcing it to produce lab tests results on the "cocaine".

James E. Turk, the prosecutor who handled the case will say only "it came back negative."

"That's because it was bubble gum," says Jerry Froelich, McClendon's attorney. A Judge returned the McClendon's items.

Turk considers the search "a good stop. They had no proof of where they lived boyond drivers' licenses. They had jewelry that could have been contraband, but we couldn't prove it was stolen. And they had more cash than I would expect them to carry."

McClendon says: "I didn't see anything wrong with them asking me to search. That's their job. But the rest of it was wrong, wrong, wrong."

SELLER, BEWARE

Owners who press the government for damages are rare. Those who do are often helped by attorneys who forgo their usual fees because of their own indignation over the law.

For nearly a decade, the lives of Carl and Mary Shelden of Moraga, Calif., have been intertwined with the life of a convicted criminal who happened to buy their house.

The complex litigation began when the Sheldens sold their home in 1979, but took back a deed of trust from the buyer - an arrangement that made the Sheldens a mortgage holder on the house.

Four years later, the buyer was arrested and later convicted of running an interstate prostitution ring. His property, including the home on which the Sheldens held the mortgage, was forfeited. The criminal, pending his appeal, went to jail, but the government allowed his family to live in the home rent free.

Panicked when they read about the arrest in the newspaper, the Sheldens discovered they couldn't foreclose against the government and couldn't collect mortgage payments from the criminal.

After tortuous court appearances, the Sheldens got back the home in 1987, but discovered it was so severely damaged while in government control that they can now stick their hand between the bricks near the front door.

The home the Sheldens sold in 1979 for $289,000 was valued at $115,000 in 1989 and now needs nearly $500,000 in repairs, the Sheldens say, chiefly from uncorrected drainage problems that caused a retaining wall to let loose and twist apart the main house.

Disgusted, they returned to court, saying their Fifth Amendment rights had been violated. The amendment prohibits the taking of private property for public use without just compensation. Their attorney, Brenda Grantland of Washington, D.C., argues that when the government seized the property but failed to sell it promptly and pay off the Sheldens, it violated their rights.

Between 1983 and today, the Sheldens have defended their mortgage through every type of court: foreclosures , U.S. District Court, Bankruptcy, U.S. Claims.

In January 1990, a federal judge issued an opinion agreeing the Sheldens' rights had been violated. The government asked the judge to reconsider, and he agreed. A final opinion has not been issued.

"It's been a roller coaster," says Mrs. Shelden, 46. A secretary, she is the family's breadwinner. Shelden, 50, was permanently disabled when he broke his back in 1976 while repairing the house. Because he was unable to work, the couple couldn't afford the house, so they sold it - the act that pitched them into their decade-long legal quagmire.

They've tried to rent the damaged home to a family - a real estate agent showed it 27 times with no takers - then resorted to renting to college students, then room-by room boarders. Finally, they and their children, ages 21 and 16 moved back in.

"We owe Brenda (Grantland) thousands at this point, but she's really been a doll, " says Shelden. "Without people like her, people like us wouldn't stand a chance."

CIVIL FORFEITURES CAN THREATEN A COMPANY'S EXISTENCE

For businesses, civil forfeitures can be a big, big stick. Bad judgment, lack of knowledge or outright wrongdoing by one executive can put the company itself in jeopardy. A San Antonio bank faces a $1 million loss and may close because it didn't know how to handle a huge cash transaction and got bad advice from government banking authorities, the bank says. The government says the bank knowingly laundered money for an alleged Mexican drug dealer. The problems began when Mexican nationals came to Stone Oak National Bank, about 150 miles north of the border, to buy certificated of deposits with $300,000 cash. The Mexicans planned to start an American business, they said. They had drivers' licenses and passports. Bank officers, who wanted guidance about the cash, called the Internal Revenue Service, Secret Service, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, the Federal Reserve, and the Department of Treasury. Federal banking regulators require banks to file CTRs - currency transaction reports - for cash deposits greater than $10,000. That paper trail was created to develop leads about suspicious cash. Once the government was alerted, the thinking went, it could track the cash, put depositors under surveillance or set up a sting. A tape-recorded phone line that Stone Oak, like many banks, uses for sensitive transactions captured a conversation between a Treasury official and then-bank president Herbert Pounds. According to transcripts, Pounds said: "We're a small bank. I've never had a transaction like that.....I talked to several of my banking friends. They've never had anybody bring in that much cash, and the guys say they've got a lot more where that came from." Pounds asked for advice and was told to go through with the transaction. "That's fine...as long as you send the CTRs," the Treasury official said. "That's all you're responsible for." The bank took the money and filed the form. Between that first transaction in March 1987 and the government's March 1989 seizure of $850,000 in certificates of deposit, bank officials continued to file reports, according to photocopies reviewed by The Pittsburgh Press. "The government had two years to come in and say, 'Hey, something smells bad here,' but it never did," says Sam Bayless, the bank's attorney. But the government now charges that the bank customers were front men for Mario Alberto Salinas Trevino, who was indicted for drug trafficking in March 1989. Fourteen months later, the bank president and vice president were added to the indictment and charged with money laundering. The bank never was criminally charged, and the officers' indictments were dismissed May 29. The U.S. attorney's office in San Antonio said it would not discuss the case. Because the Mexicans used their certificates as collateral for $1 million in loans from Stone Oak, the bank is worried it will lose the money. In addition, according to banking regulations, it must keep $1 million in reserve to cover that potential loss. For those reasons, it has asked the government for a hearing and has spent nearly $250,000 for lawyers' fees. But the bank can't get a hearing because the forfeiture case is on hold pending the outcome of the criminal charges. And the criminal case has been indefinitely delayed because Salinas escaped six weeks after he was arrested. Because the bank is so small, the $1 million set-aside puts it below capital requirements, meaning "regulatory authorities could well require Stone Oak National Bank to close before ever having the opportunity for its case to be heard," says its court brief. To brace for a loss, Stone Oak closed one of its branches. "For the life of me," says Bayless, "I can't understand why the government would want to sink a bank. And, to boot, why would the government want another Texas bank?" Bayless, who says, "I'm very conservative, I'm a bank lawyer, for heaven's sake," derides the federal action as "narco-McCarthyism." Problems with paperwork also led to the seizure of $227,000 from a Colombian computer company. The saga started in January, 1990 when Ricardo Alberto Camacho arrived in Miami with about $296,000 in cash to pay for an order of computers. Camacho is a representative of Tandem Limitada, the authorized dealer in Colombia and Venezuela for VeriFone products, says VeriFone spokesman Tod Bottari. The cash covered a previously placed order for about 1,600 terminals. Both the government and Camacho agree that when he arrived in Miami, he declared the amount he was carrying with Customs. They also agree that the breakdown of the amount - cash vs. other monetary instruments, such as checks - was incorrect on his declaration form. Camacho and the government disagree about whether the incorrect entry was intentional - the government's position - or a mistake made by an airport employee. The airport employee, in a deposition, said he had filled out the form and handed it to Camacho for him to initial, which he did. "Mr. Camacho assumed the agent had correctly written down the information provided to him," says Camacho's court filings over the subsequent seizure of the money. The government says Camacho deliberately misstated the facts to hide cash made form drug sales. Camacho brought in the suitcase full of U.S. cash which he had purchased at a Bogata bank, because he thought it would speed delivery of his order, he told federal agents. VeriFone lawyers directed Camacho to deposit the money in their account in Marietta, Ga, says Bottari. The final bill for the computers was $227,000. VeriFone arranged for an employee to meet Camacho at the bank and told the bank he was coming, Bottari says, The bank notified U.S. Customs agents that it was expecting a large deposit. When Camacho arrived, federal agents were waiting with a drug-sniffing dog. The agents asked Camacho if he would answer "a few questions about the currency." Camacho agreed. The handler walked the dog past a row of boxes, including one containing some of Camacho's money. The dog reacted to that box. At that point, the agents said they were taking the money to the local Customs office, where they retrieved information from the report Camacho had filed in Miami. The reporting discrepancy, and the dog's reaction, prompted the government to take the cash. Although the computer deal went through several weeks later when Tandem wired another $227,000, that wasn't enough to convince Albert L. Kemp Jr., the assistant U.S. attorney on the case, that the first order was real. After the seizure, Kemp said, the government checked Camacho's background. He is a naturalized American citizen who went to business school in California and then returned to help run several family businesses in Colombia. He travels to the United States "four of five times a year," says Kemp. "He has filled out the currency reports correctly in the past, but now he says there was a mistake and he didn't know about it. "C'mon," says Kemp. "In total his whole story doesn't wash with me." "We believe the money is traceable to drugs, but we don't have the evidence. So instead of taking it for drugs, we're using a currency reporting violation to grab it."

Part Four: THE INFORMANTS

by Andrew Schneider and Mary Pat Flaherty

Crime pays big for informants in forfeiture drug cases