Into the vortex: linking armed conflict to drug trade

Drug Abuse

Introduction

Drugs cause a large number of fatalities every year. Not because they used the drugs and overdosed, but as the result of the violence that seems inherent to the contraband. Despite its increased importance – opium is an essential link in the Afghanistan conflict, the escalation of the Mexican cartel war – the drug trade has received little attention in the field of political science.

The central question in this work is why drug trade and armed conflict are so often associated with each other. It turns out that the drug trade and armed conflict reinforce each other, hence contributing to a symbiotic relationship.

A more detailed answer to the central question is provided by this work. By uncovering mechanisms that explain the relationship between drugs trade and armed conflict, a number of policy advises are given at the end of the work.

In order to give an appropriate answer to the question, it needs to be investigated how drug trade and armed conflict affect each other. Thus the first question that is asked is how comes that drug trade is concentrated in conflict areas. The answer is best understood from an economic point of view; conflict areas, or places that experience political instability are the ideal business environment for the drug trade. Since drugs are illegal, the industry has to find its refuge into areas that experience no effective control from the authorities. Moreover, the destructed economies of these regions cause that the industry will flourish, as it is one of the few economies that are present in conflict zones.

The other main question is how the drug trade contributes to an intensification in violence. There are three essential mechanisms that are pointed out. First, the illegality of the good makes that it is naturally linked to areas without political control. Furthermore, the illegality makes the good controversial and triggers aggressive counternarcotics programs, which essentially means an escalation of violence. Secondly, the large amounts of money that are tied to the drug trade bring corruption, which fosters the ineffectiveness of the state. Thirdly, drug related conflicts disrespect borders; international drug flows make the drug trade an international problem, that triggers international solutions in the shape of counternarcotics. A fourth section is added, explaining that some factors are often overlooked; geographical features, history and culture are essential to comprehend if one wants to effectively end the conflict.

The emphasis in this work is on conflict resolution. Thus the central question and the policy advises that follow are aimed at resolving the conflict – as opposed to e.g. ending the drug trade. It will be demonstrated that the drug trade can decrease or vanish as part of a conflict resolving strategy. This work takes a deductive approach; earlier developed theories are scrutinised and case studies are examined.

This study is structured as follows: the next chapter deals with the state of art on this subject. What has been written and where does this study position itself compared to earlier works. The second

definitions of conflict and drug trade in order to set the frame. In short; both drugs and conflict are interpreted as rather broad concepts in order to increase the scope of this study.

The following chapter explains how armed conflicts act as a facilitator for drug trade. The main arguments are economic; microeconomic stakeholders theory demonstrates the motives of actors on the ground for participating in drug trade. Macroeconomic perspectives provide a more structural and holistic approach and argues for the assumption that whatever happens in one place, affects what is happening elsewhere. Finally, this chapter also focuses on the historic role of drug trade in certain areas. History partly explains why certain areas are significant drug producing countries. Thus in short; this chapter deals with the first major question on why conflict attracts drug trade.

The following chapter deals with the second question of importance; what the effects are of the drug trade on the conflict. The main focus is on how drug trade fosters the conflict. This chapter contains a set of four main arguments that are overlapping and complementary. The illegality of drugs, the huge sums of money, the border crossing potential and geography and culture are the main mechanisms that intensify the conflict when it comes to drugs.

Following this chapter, we move to the policy recommendations for drug trade and conflict in general. As stated, the main aim of these recommendations is to resolve the conflict. The final chapter will deal with the overall conclusion.

State of Art

This chapter is intended to clarify the position of this research vis-à-vis other works in this field. This is done by outlining a number of issues that have been subjected to debate, a literature review, and a summarizing statement on where this study converges and differs from earlier works.

The main justification for this work is that there have not been any systematic attempts to capture the role of the drug trade in armed conflict.1 Most literature on drug trade and armed conflict is in the field of natural resources of armed conflict. Thus, it generates theory on natural resources as such, meaning that the role of drug trade is marginalised in a trade off for generalisation. Another raison d’être of this work is that the role of drug trade in armed conflicts seems to gain importance. Present day insurgencies are funded to a significant extent by the drug trade.

Drugs as part of a wider debate

This research approaches the drug trade from a security studies and political economy approach. The conclusions presented at the end of the paper, and the policy recommendations that are derived from them, are thus presented from in the light of conflict resolution.

However the drug trade is part of a larger debate, where not all policies serve the same goals. For instance, it is be argued that the illegality of drugs is what makes it linked to conflict. Thus, some would say, legalisation might be an option in order to nip the conflict in the bud. This would encounter serious resistance from people who view the drug problem from a public health paradigm. In other words, there will never be an ideal solution and the question is not how to stop drugs once and for all, but rather how to find a balanced compromise and effectively manage the negative sides of the drug trade. However, this is beyond the scope of this paper.

Literature review

Literature relating to the topic of drugs and armed conflict are diverse and range from case studies, to more general statistical studies, to attempts to formulate mid range theories on natural resources and civil wars. Furthermore, the previous paragraphs mentioned midrange theories on drug trade and natural resources. Then again, there are actually few attempts made to theorise the specific role that drugs can play.

This study owes gratitude to the case studies. There were plenty of scholars who invested time and energy to investigate the political economy of armed conflict in countries such as Afghanistan, Burma, Colombia, Mexico and other cases. Not all studies devoted the same amount of energy on the drug trade, as it became quickly clear that the drug trade is only one of the plurality of – illicit – economic activities that are present in conflict situations.

The second range of literature were the statistical studies that investigated the correlation between armed conflict and natural resources.2 The primary debate in these studies is whether economic benefit – greed – or political conflict – grievance – were the main drivers in civil wars. Their findings were that greed matters most in civil war.

The statistical research caused some controversy. Qualitative scholars looked at cases individually and, correctly, stated that concluding that all civil wars are actually motivated because of the material profits is too simplistic.3 It turns out that the main focus of their work was to develop a successful midrange theory that focuses more on the features of natural resources – lootability, obstructability, legality4 – and the stakeholders that are involved. In other words, it is a Political Economy approach to the problem.

This work

This work focuses mainly on the role of the drug trade in armed conflicts. This has proven a challenge for a number of reasons.

First, there are many factors that are linked to the drug trade that are not always easy to overlook for the sake of generalisation. Also, the more one reads into the topic, the lesser one knows as every answer seemed to generate another twenty questions. A balance has to be struck in order to speak of a holistic approach, which this research claims to adopt. It means that sometimes matters that do not directly have to with the conflict or with drugs – such as people’s culture or the climate in the case of conflict or other sources of funding like money laundering or slavery in the case of drugs – are briefly mentioned. This serves to sketch the complexity and warns against the assumption that simple solutions for complex problems actually have a chance to achieve anything – so far simple solutions only made things worse.

Secondly, accurate information is hard to obtain. This has several reasons. Conflicts and drugs are not accounted for in agencies that take care of statistics, which is understandable seen that the situation on the ground is chaotic to say the least. Furthermore, agencies that do claim to have objective numbers, often also have political agendas, which make their estimates – someone called the guestimates5 – less convincing. A quote from Ko-Lin Chin sketches the problem as follows:

US authorities projected that, in the years 2003 and 2004, between 55 and 65 percent of the opium produced in Burma cam from the Wa Hills. However, Many people in the Wa area and officials in Rangoon told me that there are other areas in Burma that are producing more opium than the Northern Wa region. “The Burmese are also actively involved in growing opium,” a district mayor told us. “It’s just that outsiders have very little information about this. Like us, we are not hiding the fact, but it is very difficult to know exactly to what level the Burmese are involved in opium growing.”6

Practically, it meant that information was sometimes intensively scrutinised for confounding variables. It is interesting to pose the question to yourself: how could you possibly find out how much drugs there is produced. Methodology varies from satellite pictures in discovering opium or coca plantations to price calculations – a lower price for heroin or opium would indicate that there is more on the market. All these methods have their fallacies as there are many confounding variables.

Thirdly, there is a lot of controversy surrounding this topic. The former point already mentioned the term “objective”. The reality is that since conflict and drugs are both matters of the well being of human beings, everybody has their own opinion about it, and no one can be taken serious when they claim to be “objective”. The controversy has led to the fact that the debate on this topic has often been deadlocked because people stuck to their ideological positions and therefore could not come with ‘out of the box solutions’. The stance of the author is that the priority is stopping the violence and let drug production and consumption be second priority, since it has been proven that combating both is impossible. Guaranteeing of basic human rights – bringing an end to the violence – saves more lives than countering drugs. Thus a rather liberal stance on drugs is taken. Bear this in mind when reading the chapter on recommendations.

So, leaving the biggest challenges aside, what actually has been done?

First of all, this work also adopts a Political Economy approach. Basically this entertains Harold Lasswell’s question of who get’s what, when and how? The “who’s” are the actors in this story, thus the stakeholders in the drug trade.7 The “what’s” is obviously the drugs, but also the money and in turn the power that is attached to it. “When” is a more difficult question to answer, but in short it would mainly refer to the present and future. One of the justifications for this work is the assumption that in this dynamic world, illicit war economies will gain importance for present day and future armed conflicts. The “how” is actually the main focus of this study. How is drugs playing a role in the conflicts that are attended. The “how” also linked back to earlier problems: Political Economy has a tendency to approach problems holistically – meaning that everything is connected. To get to understand the “how” meant to get far deeper into individual cases – matters such as history and culture came into play.

This leads to a second matter: the empirics. This study is greatly indebted to the numerous case studies that have been undertaken on the conflicts and political instability such as Afghanistan8, Burma9, Colombia10 and Mexico.11 It should be noted on beforehand that it turns out that limiting the cases to states as territorial units will turn out to be a handicap. The armed conflicts, and the drug trade even more, do not respect the boundaries made by man and recognised by the international

community. Furthermore, country reports, reports on the global drug industry, and policy briefings were used as sources – but with a sceptical look of course!

The essential thing to do was to define armed conflict and violence. The trouble is that conflicts involving the drug trade can mean various things; the occasional murder to an all out war. Therefore, a more complex definition of violence is in place that takes into account the dynamics and changeable character of war. Violence comes, in most cases, in waves – Afghanistan is the only example of sustained high intensity warfare. Also drugs were interesting to define. Drugs are not necessarily natural resources; opium, cannabis and coca are indeed agricultural products, amphetamine type stimulants, or ATS such as crystal meth, are chemicals. However, for the sake of convenience, this paper tried to focus mainly on opium and coca and the cases of ATS were mentioned when needed.

This led to the second point; explaining how armed conflict and drugs found each other. This basically is the body of the work. This point was inspired by Ram Manikkalingam, who suggested to start from the simple but useful questions: “how is drugs good for conflict” and “how is conflict good for drugs”. It was further elaborated upon when Tom Kramer mentioned that one of the key questions in the literature is the chicken or egg dilemma; did the conflict cause the drugs, or did the drugs cause the conflict. This work has a threefold answer to the question; in some cases its the former, in others the latter, but in most cases armed conflict and drug trade act symbiotically. This three way answer will probably encounter some critiques, as policymakers want things simple and straight. The truth is that social reality is not simple and straight; many different viewpoints contribute to many parallel realities. The author has a strong aversion against mono causal explanations, which were often applied in earlier literature.12

Definitions: Conflict & Drugs

This chapter deals with the definitions and characteristics of conflict and drugs. This is needed as interpretations of conflict and drugs are diverse.

The first subsection defines the characteristics of conflict. Central issues concern the monopoly on violence, economic degradation, the concept of modern wars and finally, motives for conflict. The following subsection deals with the definition of drugs. Most important here is that drugs are lootable, unobstructable and illegal. This will be illustrated with an example from Afghanistan. Finally, an important assumption of this work is that despite counternarcotic efforts, the world will never get rid of drugs, for better or worse.

Characteristics of conflict

The conflicts attended in this study vary to a great extent. The essential issue is that a given area experiences political instability over a longer period of time. Features such as the number of casualties per year are not really relevant to this study, as violence can intensify in one year and the next year can be relatively peaceful. Violence comes in waves, fostering the insecurity which, for reasons explained onwards, acts beneficial for the drug trade.

Examples of differing levels of violence can be depicted as follows: some countries experience an outright war, such as Afghanistan. Then again, the degree of violence in Burma has strongly decreased over the last couple of years, however recently fighting has resumed – one can speak of a rather instable cease fire. In Mexico, the conflict is more characterised by gang wars with political murders that has increased over the years.

However, no matter how different the cases are, certain principles can be traced in all cases. The most important feature of conflict is that there is no monopoly on violence, resulting in a plurality of power centres. Economic degradation is also a recurring theme, meaning that the destruction of infrastructure leads to income uncertainty. In short: conflicts are about economic and political power. Following that, the notion of “modern warfare” is explained. It is important to see that a conflict fulfils certain functions and that there are stakeholders – in contrast to the conventional notion of war as “irrational” and purely destructive, as many liberals argue. The final subsection is concerned with the motives of conflict. This contains a distinction between politically and economically motivated wars. This distinction is also know as the greed or grievance thesis.13

Monopoly on Violence

Essential in a conflict situation is the absence of a monopoly on violence. The lack of a monopoly of violence results in a plurality of power centres, instability and anarchic chaos. This in turn triggers a competition by various groups who all seek power – for different reasons – and thus control of

territory. What results is an alternative division of territory with unclear borders; sometimes there are grey zones, sometimes they are clearly defined. The essence is that the politics differ within these territorial units. Thus within a state, different political systems – meaning laws and economic systems – arise. One can best describe these areas as “de-facto states”: an alternative mode of economy and a different kind of law enforcement. These new judicial and economic systems mean that different laws and different modes of production exist. With relation to the drug trade it means that the production of drugs is accepted as a way of making money – since there is no central government that has the means to effectively maintain prohibition laws.

How this alternative division of territory and power arises, often depends on history. The power division can be structured along different cleavages in the population; one can think of ethnicity, religion, economic classes for example. In Afghanistan, the central cleavage is between the Taliban and the Western backed government in Kabul. The Taliban is mainly comprised of religious extremist Pashtuns. In Burma, the cleavages are organised along the lines of ethnic groups such as the Wa or Karen in the North eastern part. In Colombia, the paramilitaries are a reaction to the division of wealth established by the central government in Bogota.14

Economic degradation

A second essential feature of conflicts is that conflicts generally mean the destruction of the economy. Huge amounts of capital, production facilities, infrastructure, and markets are destroyed as a result of the insecurity and physical destruction. The implications of this physical destruction is that opportunities to generate revenue are limited. Next to the limitation of economic opportunities, the lack of effective control or alternative modes of control, this situation also brings about certain economic functions. So the violence brings destruction, the anarchy different economic functions, and in all this there are still people who try to make money – drugs one of the industries that flourishes under these conditions.

Jonathan Goodhand stresses the different kinds of economies that arise based on the needs of the actors involved.15 He sketches three different sorts of economies in a conflict situation: the coping economy, the combat economy, and the shadow economy. The coping economy refers to a survival economy for “ordinary people”, people who have no direct interest in the conflict. In practical terms, the coping economy often refers to the peasants who engage in harvesting the drug crops such as opium poppy or coca leaf. However, it could also refer to combatants who get a soldiers salary in order to keep themselves and their families alive. The combat economy refers to the money that is generated in order to keep the war effort going. Warlords often profit from this by taxing the drug trade that is in the area under their control – remember the lack of monopoly on violence. The shadow economy is actually the smallest group, probably making the largest profits. The shadow economy consists of entrepreneurs who seek to exploit the economic functions provided by the chaos – also know as organised crime. They smuggle and trade the drugs actively, and benefit from the fact that there is no central authority and economic degradation – resulting in wide spread

corruption. This shadow economy is the only one that actually exists for the financial profit, and this is the one meant by David Keen as outlined above.16 It should be noted though that the distinction between the a combat and a shadow economy is not as clear cut as presented here. Often, the two coincide, causing even more complexities for analysing this topic. However, the convergence of shadow and combat economies will be dealt with in another chapter.

Modern wars

A recent debate in political science and conflict studies is the phenomenon of “modern warfare”.17 Although definitions of modern warfare vary, this defines modern war on the basis of a dual set of principles; the decreasing importance of the nation state and the alteration of terms of “winning” and “losing”.18

Firstly, present day armed conflicts seem to go beyond the nation state. This can be the result of innovations, such as in communication and information technology or “forces of globalisation”19, or the fact that the nation state has been an artificial construct in many areas of the world. Martin van Creveld notes that communication is an essential feature that determines strategy of a faction.20 Inventions such as internet and cell phones altered and enhanced non-state violent actors’ capacity to conduct asymmetric warfare. Another cause that results in decreasing importance of the state in modern warfare is because in some areas of the world, states are constructs that do not match with the composition of the population – such as ethnicity or religion. Africa is a good example of where the state system does not match with societal reality at all. The borders on the African continent were products of colonial divide-and-rule tactics. But also some borders in Central and Southeast Asia came into existence without the say of the people who actually live there. Again, the Afghan and Burmese states contain a plurality of ethnicities. In turn, these ethnicities occasionally stretch beyond the borders; ethnic Tajiks living together with the ethnic Pashtun in Afghanistan, whilst the Tajiks are also in neighbouring Tajikistan. Similar examples exist in Burma or West-Africa as well. The result is that conflicts are not confined to territorial units that are internationally accepted as states. So in short: violence gets “privatised” in the sense that non-state actors will play a significant role in armed conflict and conflicts get “borderless”.21 Concurring with these observations is the fact that the number of interstate wars is decreasing.

Secondly, the very nature of warfare has changed. In contrast to Clausewitzian logic, wars are no longer necessarily to defeat the enemy. Instead, the state of conflict seems to be a means to an end – hence the continuing state of violence. David Keen pointed out in an article that conflicts are often viewed as irrational happenings, where everybody loses seen the loss of life, the disruption of

society, and the economic degradation.22 However, he argues, there are winners during a state of war if one asks the question on who benefits during a war. Arguably, there are some industries that naturally thrive in a state of conflict. In this respect one can think of the arms industry, but also the drug industry flourishes. This would support the grievance thesis, which is touched upon in the state of art.

So how relevant is this debate on modern warfare for drug trade?

To answer this question it is useful to consult the development of history since the Cold War. During the Cold War era, the world was roughly divided into two blocs: the United States and its capitalist economy versus the Soviet Union and its communist economy. Their competition for global power meant that parties that were part of local or regional conflicts – e.g. in the Middle East, southeast Asia or Latin America – could seek military or financial support from either of the Cold War blocs, as the opposing party was likely to support the other. To make a long story short; during the Cold War, warring factions could seek assistance from the US or USSR – when this faction was a non-state actor, one would now speak of state sponsored terror. As the Cold War came to an end, alternative sources for the funding of – violent – political causes had to be found.23 The drug trade proved to be one of the most lucrative options. Other “modern” ways of funding causes often intersect with drug trade, and each one is worth a specific research. Examples are the trading in small arms; the trafficking of human beings, mainly more vulnerable groups such as women or children, for either slavery or prostitution; money laundering; trading in alcohol or cigarettes.24

Secondly, globalising forces had a major impact on the global economy. The “compression of time and space” implied more mobility to move goods from one point in the world to another. This also had profound effects on the illicit global economy25, such as the trafficking in drugs or any of the commodities mentioned in the former paragraph. International organised crime also takes advantage of these innovations.

The term “modern war” is perhaps misleading as non state armed actors have existed for a longer time and economic benefit has more often been an incentive.26 Alfred McCoy notices that the Chinese nationalist Kuomintang – KMT – forces during the Chinese Civil War exploited the opium trade as a war economy. However, it can be argued that wars fought by transnational groups with economic and political motives are becoming more prominent nowadays and, in that sense, are a departure from Cold War patterns where one of the bipolar blocks supports proxy armies in order to undermine either capitalist or communist expansion – one can think of US support to the Mujahedeen in Afghanistan or Soviet support to the North Vietnamese. A factor that would refer to “modern” warfare, especially its political economy, is the effect of globalisation through innovations in communication and transport technology. Access to markets has improved as a result of globalisation, so it is much easier to obtain money with illicit resources. Evidence furthermore

suggests that drug traffickers become more and more sophisticated in organisational and military capabilities. Drugs are trafficked via airplanes or even submarines.

So concluding we can state that modern day conflicts have a strong non-state component; wars get borderless and are fought to some extent by non-state actors. In this setting, the illicit economies will serve as a war economy – in particular drugs – since the innovations in communication and transport industry have enabled non-state actors to set up globalised trade networks. The major implication is that wars are dynamic, not static happenings.27 The diversity in actors and the chaos make conflicts difficult to analyse. Defining wars as two parties who combat each other to gain the upper hand is simply not sufficient anymore.

Motives of conflict

This sub paragraph mainly reflects on the greed and grievance theses. As mentioned in the state of art, there are roughly two motives for conflict; greed or grievance. Greed refers to the situation that conflict brings with itself economic functions of chaos; the break down of order means that illicit branches thrive. So the instigators of conflict would do so because it brings them financial benefit. This study will classify the greed thesis as financially motivated actors, or organised crime. Important of the financially motivated actors is that they are primarily interested in maintaining the status quo, as this provides them with substantial income. Moreover, it does not necessarily matter whether they live in a war or peace situation, as organised crime also exists in peaceful societies.28 However, it is important to remember that seen the fact that drug production is illegal, hectares of coca leaf or opium poppy are unlikely to be found in states with effective law enforcement administrations. An example of a primarily financially motivated conflict is Mexico. Political stability has been undermined by drug cartels who have taken over power in a number of areas. Movements that advocate political change with violent means are not so significant in this conflict, thus it is mainly organised crime that engages into politics now that they have successfully undermined the government. Financially motivated conflicts are often very blurry as government officials can be double hatted; on the one hand, they claim to support the law enforcement agencies that deal with counternarcotics, yet on the other hand they might well turn a blind eye since they are in the payroll of drug traffickers. In Colombia, it is more the system of political economy that matters – right winged against left winged groups concerning land appropriation.29

The grievance thesis holds that conflicts erupt because of political reasons; one can think in terms of ethnicity or religion, and often history plays a large role. The violence that is in place is mainly to serve the ideals of political change. Breaking down order means replacing it with a new framework, which is often the ideology of a group. The instigators of a conflict are political insurgents who aim at change, rather than status quo. Good examples of political conflicts could be Afghanistan or Burma. In Afghanistan and Burma, significant ethnic cleavages have played a role in how power is divided.

An important difference between the two is the nature of the motivation. Financially motivated organised crime groups are often interested in maintaining the status quo, as this is a situation that

provides them with a lot of money. This is regardless on whether it is war or peace, as peaceful countries also experience organised crime. Politically motivated groups are fundamentally different in the sense that they are a revisionist force, in contrast to status-quo oriented. Political movements such as the militias in northeast Burma strife for political change. Having said this, and as will be shown in the following chapters, the distinction between militias striving for money or political change is not always clear cut as motives can overlap. This contributes to the overall complexity of drug funded conflicts. Resolving these conflicts effectively though, means finding a solution for these mixed motivated groups.

Recapture

So to summarise what has just been said on conflicts; first of all, the absence of a monopoly of violence causes different factions to compete for power. The motivations to do so vary to a great extent, but one can make a rough distinction between economically and politically motivated groups. The second major characteristic of armed conflict is the economic degradation it brings with itself. The destruction of infrastructure obstructs the production of commodities and access to markets, which has a big impact on the people living in the area. Finally, the phenomenon of “modern warfare” was discussed. Non-state armed groups depending on illicit economic networks to support their war effort pose a challenge to the Westphalian state system. Furthermore, the increased mobility and communication as the result of innovations in technology have resulted in a more globalised illicit network, meaning that illicit trade chains stretch over thousands of kilometres – for example the drug trade chains from Afghanistan or Colombia to Europe.

Characteristics of drugs

The previous paragraph dealt with the setting of conflict. It turns out that conflicts bring a state of insecurity and economic degradation. Earlier it was already mentioned that the drug industry seems to be capable to fit in this economic vacuum and provide an income for actors involved. This paragraph deals with the features of drugs in order to understand why drugs fill the gap.

What is important to remember is that drugs are a very lucrative source. Revenues are relatively high. Additionally, it should also be taken into account that drugs are relatively easily to produce and traffic. This part lines out the features and economic functions of drugs. At the end of the chapter, the fundaments should be clear for the merger between drugs and conflict.

This paragraph goes in depth on its political ecology30 as Philip Le Billon has described it, and further gives an example of the value chain of opium in Afghanistan. The political ecology mainly has to do with how a natural resource behaves in a certain environment. In short, Le Billon states that the impact of a natural resource on a conflict depends on three features: its lootability, its obstructability, and whether it is legal or not. These features impact the social, political and economic environment around it.

Lootable

When a natural resource is lootable, it is meant that it can be acquired with relative ease. For example, opium poppy is easily acquired as it only needs some agricultural effort and basic skills when harvesting the opium. In contrast, deep shaft diamonds need intensive effort and infrastructure to get out of the ground. Additionally, drug crops grow back every year, instead of diamond mines that are at a certain point exhausted of the minerals they harboured. Drug crops are in general rather lootable, thus easily acquired by “simple” farmers, or anyone else interested in acquiring them.

Yet the fact that most drugs are agricultural products, or derivatives from drug crops, means that there is a strong geographical dimension. The climate plays an essential role in the quantity and quality of the harvest. Not all drugs studied in this research have an agricultural background. Examples are amphetamine type stimulants – or ATS – that gain prominence in southeast Asia.31

Heroine and cocaine are derivatives from agricultural goods – opium poppy and coca leaf respectively. The production chain of these goods consists of multiple professions; peasants who plant and yield the crops, chemists who refine it into heroine or cocaine, and finally the dealers.

Obstructable

Overall, drugs are not very obstructable. Drugs are easy to move around – especially in areas with limited law enforcement capabilities and porous borders. Moreover, seen the high revenue that is attached to the drug trade, smugglers have thought of creative mediums to transport drugs. An example of an obstructable good would be oil that travels via pipelines. Blow up one pipeline with a simple explosion device – which can be found plenty in conflict zones – and no more oil will reach its intended destination.

Illegal

Finally, drugs are universally banned. Global regimes have caused that every country formally supports the UN Single Convention from 1961, where psychoactive narcotics have gained the status of illicit good.32 What does its illegal status matter? Le Billon argues that economies that have traditionally relied on revenue of drug crops get a criminalised status from a Western perspective.33 Certain Latin American countries have a large drug industry simply because of the income it provides, and because of the coca leaf tradition. What happens now is that governments – domestic and foreign – actively pursue these people, thus resulting in some form of conflict. A second important function of its illegality – not mentioned by Michael Ross or Philip Le Billon – is what happens to the price. The question posed earlier on why drugs are so lucrative is quickly answered by pointing out that the fact that it is illegal causes its price to rise.34

Example: Afghani opium

Now follows an example on the production chain of Afghani opium. This should clarify the inherent characteristics of opiates – lootability, obstructability, illegality. Afghan opium or heroin go through a production and value chain that is part of conventional economics. Opium is gained from a mature papaver somniferum – or opium poppy – that is cut by a famer with a specially designed knife; the opium paste comes out of the flower bulb and is collected by the farmer. This process demonstrates how lootable opium paste is. It should not forgotten however, that the reason it is lootable is mainly because it requires no highly developed skills. It is, as many agricultural processes, a very laborious task.

The next step for the opium cultivator is to sell the opium gum at farm gate prices.35 They do this either at home to a small time opium trafficker or they sell it at special opium bazaars. It has to be mentioned that opium cultivators are not nearly paid the equivalent of the astronomic prices that a gram of pure heroin can make in consumer countries such as the US or Europe.

The small time trader at the bazaar then sells the opium gum to heroin refineries, or laboratories, if they are not part of that chain themselves. In the lab, the opium gum is chemically refined into heroin. The heroin then gets sold on to big or small traffickers who get it across the borders, where it is consumed or sold on.

So the price of the good rises with every step it takes in the production chain, just as any other good in capitalist society. However, the vast price increases are the result of the risks that are attached, and consequently the bribes that have to be paid in order to successfully smuggle it to the next stage.36 The bribe is simply another cost of production, which is calculated into the price of the good once it gets sold. Another prominent feature in this study is the mechanism of corruption, but this will be attended later.

Never ending story

A critical assumption of this work is that drugs are here to stay. Bluntly, every demand creates its own supply and the demand for drugs consists of addicts or people wealthy enough to use party drugs. It is a lucrative source with a steady demand. But also the characteristics of drugs as such – being lootable, inobstructable, and profitable through illegality – make it utopian to think that one can manage to rid the world of narcotics. Nadelmann formulates it as follows:

Drug prohibition laws, like prohibition laws against prostitution and gambling, can powerfully affect the nature of the activity and the market, but they cannot effectively deter or suppress most of those determined to participate in the activity.37

Political Economy

The previous chapter set out the definitions of drugs and conflict. This chapter explains how the drug trade and armed conflict are made for each other from the perspective that conflict ridden areas are good business environments for entrepreneurs in the drug industry – or organised crime. The main argument in this chapter is that the link between drug trade and armed conflict is best explained when one adopts a political economy approach. Basically, this chapter forms the theoretical foundation.

This chapter is structured as follows; first of all, a micro-economic approach is set out on the basis of Goodhand’s distinction of three economic functions; coping economy, combat economy and shadow economy. Following this paragraph, a macro-economic story is presented that sheds light on the global drug trade. Countries with weak law enforcement capacity function as the perfect business environment for drug production. Thirdly, this chapter argues that understanding the history is important to understand the role of drugs in the conflict, as each drug based conflict has its own specific characteristics.

Micro-economy: cui bono?

This section attends the stakeholders in the drug economy. Who depend or profit from the production and trade and what are their motivations? It is important to understand who the stakeholders are as this provides an overview of the dynamics of the conflict. Furthermore, it presents policymakers or consultants with the interests of the parties involved. It is essential to know who benefits in order to come up with solutions, as it presents an overview on the ones affected by policies.

The clearest attempt to theorise stakeholders in this story was is undertaken by Jonathan Goodhand.38 Goodhand distinguishes three sorts of economies, and thus three kinds of stakeholders in Afghanistan’s opium industry: the coping economy, the combat economy, and the shadow economy. Although initially designed for Afghanistan, it turns out that his typology of stakeholders can be generalised to a number of other cases as well.

Coping economy; in short, the coping economy refers to people who try to maintain themselves or survive. In most of the cases, the coping economy refers to the grass root level or the first step in the value chain. Growing opium or coca in countries such as Afghanistan, Burma, or Colombia is mainly done by peasants who sell the crops for a relatively modest price.39 In depth research by Ko-Lin

Chin40 in Burma, or MacDonald41 or Mansfield42 in Afghanistan make clear that motivations for growing opium are related to house hold level decision making and thus are very diverse. Motivations range from survival, improve living conditions, forced labour, paying opium tax are motivations heard in a survey in Burma.43 In Afghanistan similar motivations play a role yet what is also frequently mentioned in that the local credit system – known as zakat – rests on opium incomes.44 Moreover, the effects of the climate and seasons play a large role in the decision making of farmers. But coping strategies and drugs are not necessarily linked directly. One should also take into account that many other ways of making money – such as corruption, joining a militia, or being a truck driver – are part of coping strategies derived from the drug trade in economically underdeveloped areas.

Yet the coping economy does not only refer to the peasants. This becomes apparent if we look at countries that are not so much the production countries, but rather the trafficking countries. Mexico experiences a relatively low production of drug crops and functions more as a transit country between the Andean states and the US. Nevertheless, the drug industry produces a large number of secondary jobs.45

Although reasons vary, overall one can concur with the remark of Vanda Felbab-Brown that the drug industry is fuelled by opportunity and necessity.46 Central to the coping or survival economy is the fact that drugs are lootable and can thus be acquired without too sophisticated instruments. The economic devastation results in the necessity to engage in practices that are otherwise viewed as morality.

Combat economy; the second group of stakeholders in the drug industry are political insurgents. Shortly stated, the drug trade forms an economic war economy for certain groupings. The combat economy enjoys larger profit margins as the revenue of insurgents is mainly done through taxing the drug trade. As Rubin and Sherman stated, political insurgents or warlords control territory that enables different functions; terrain where drugs can be grown, transit routes, space for drug refineries and so on.47 All the people who use the land – either for growing, refining, or trafficking drugs – are subjected to the law of the political power that is in charge.

The insurgents enjoy almost a natural advantage over the government. Michael Ross stated that due to the illegality of drugs, it is highly unlikely that the government will engage actively in the production of drugs.48 Seen the international prohibition of drugs Ross is right that a government will refrain from active illicit drug production or face international sanctions. However, a nuance should be in place as the government and its agents can profit indirectly from drug trade.49 This goes in the

same way as political insurgents: taxing the drug trade, although it is more commonly known as bribery and corruption.

Shadow economy; this branch is often referred to as illegal or informal economies and the trouble is describing them without attaching value laden terms to it.50 As in any conflict, there are certain groups that profit from the conflict as such. One can think of the arms industry as most obvious example. However, also the drug trade benefits from the state of chaos as a result of the conflict, since stable states often have effective law enforcement capacities to deal with the production and trafficking of drugs.

The shadow economy are very comparable to ordinary businessmen trying to maximise their revenue by exploiting the demand for a certain commodity. War is not a necessity, since the businessmen are happy with peace as long as this brings in more profit.51 However, for drug production the most likely way to achieve big benefits is a significant drug production area, which is unlikely to be found in stable states.

Macro economy

The previous section made clear that there are several economic dimensions on the ground of a conflict with regards to drug trade. If we zoom out and have a look at international drug trade, one can also discover certain regularities and patterns on a global scale. Also, earlier in this work it was explained that effects of globalisation increased the mobility and thus the transport capacities of drug traffickers. This section outlines the mechanism of the global drug economy.

First of all, an essential mechanism is the economic law of supply and demand. Each demand creates its own supply and the drug trade is no exception. Secondly, one has to project this function of demand and supply on a global level. There is a distinction between typical consumer countries and production and transit countries. The former are usually referred to as the West, where most of the drug consumers – either addicts or recreational users – are located. The production and transit countries are less well off in economic terms and experience political instability or an unaccountable government. So one gets a world system in supply and demand countries. The supply countries are the countries that act as a production site – such as Colombia for coca, or Afghanistan for opium – and then travel through trafficking countries where the goods can be stored – West African countries for Latin American coke52 or Uzbekistan for Afghan heroin. The drugs eventually end up at the streets of cities located in the wealthier corners of the world such as Amsterdam, Los Angeles or Tokyo.

What does this have to do with conflict? Basically, most supply countries are affected by some degree of political stability. The regions and countries presented above – Western Africa, some Latin American states, Central Asian countries – either experience an armed conflict or bad governance53 that paralyse the local law enforcement systems and institutions. This lack of effective law enforcement means the flourishing of illicit practices such as drug trade. In short, instable states

form the optimal business environment for drug trade. The drug trade further provides the means to destabilise the country

An important consequence of thinking on a global scale is the so-called “balloon effect”.54 This is a consequence of the notion that every demand creates its supply. Thus drug trade will always exist as long as consumers exist – and the assumption is that drug consumption will not go away in the near future. Another assumption is that instable countries will continue to exist for a long time. Then the question arises; seen these two assumptions, how can you effectively counter the drug trade? In short: you cannot. Global prohibition regimes have thus far been unable to even come close to a drug free world. Counternarcotics can have effect on a national level, meaning that one can ban the production of drugs within a country. However, it means that the drug production will move to another place, where the business environment is better – i.e. where the governments law enforcement capacities are weaker. Hence the term balloon effect; if you press on one side of the balloon, the air inside it will move elsewhere.

Examples of the shifting of drug trade can be found all over the globe. The surge of drug trade in Mexico is the result of the closing of the Caribbean route through increased law enforcement efforts in cities like Miami, so the traders go over land.55 Now that counternarcotics efforts are increased in Texas, it is likely that the trade will shift back. The result of the zero-tolerance policies in Thailand and China meant that the heroin labs moved across the border to Burma.56 The reason Afghanistan got a notorious opium poppy producer is because it experiences political unrest for decades and because neighbouring countries such as Pakistan or Iran have engaged in aggressive but successful counternarcotics operations, meaning that the opium cultivation concentrated on Afghanistan.57 This balloon effect basically demonstrates the limits of counternarcotics: one can get one country clean, but not the entire world.

Historic factors

In some cases, but not in all, the areas that are mentioned have a history of drugs and conflict. It is important to take the history of a country into account when analysing its role in drug trade. Historic factors can impact cultural values or the way of life and can lead to a better understanding of the problem, which in turn is useful when formulating a policy. Studying the history creates a context or a frame of reference, which can help understanding what role drugs plays in economic or cultural sense for example.

A conflict is always better understood when looking at the history of it. Afghanistan and Burma suffer from political instability over decades, which is part of the explanation of why drugs is concentrated there. Furthermore, understanding the history of a conflict also sheds light on what role drugs plays – is the conflict essentially about drugs, or does it merely play a facilitating role in an ethnic struggle?

Drugs or the agricultural roots can be socially accepted and embedded in culture, such as chewing coca leaf in the Andean region, or poppy cultivation in the Golden Triangle. In the Andean region, the chewing of coca leaf is a tradition for decades that stems from the indigenous peoples. The emergence of the Golden Traingle’s as producer of opiates got significant when the defeated Chinese nationalists fled out of China and used the heroin business to sustain themselves.58 The presence of heroin in China was a result of British colonial policy that goes back until the days of the Opium Wars in the 19th century.59

However, some cases are also relatively new. West-Africa’s involvement in the cocaine trade for example, is relatively new. However, countries like Senegal experience the production and consumption of marijuana over longer periods of time.

Conclusion

So what can be concluded from this chapter? Bearing in mind the economic destruction and the lack of law enforcement capabilities resulting from armed conflict, this chapter explains who depends on the drug money, for what reason, and why the drug trade affects certain places and others not.

The stakeholders in the drug economy are threefold; the coping economy consists of people who simply need the money for survival or the household. The combat economy consists of political factions that need money in order to fund their war effort. The shadow economy consists of private actors that make a lot of money for the sake of it.

The drug trade tends to concentrate itself on areas with weak law enforcement capabilities, which is found in areas where the monopoly on violence is not effectively maintained. The lack of law enforcement is linked to the fact that drugs are illegal; in areas where the law is maintained, the risks of drug production are far greater. So it is easier to go to a place with the knowledge you are not discovered or that the counternarcotics agencies are corrupt.

How does drug trade reinforce conflict?

Earlier this work it was explained that the drug trade gets drawn into a conflict because the conflict provides the ideal economic circumstances for a black market. This chapter focuses on the reinforcing effects the drug trade has once it has settled in an instable situation.

This chapter is structured the following way; four subsections concentrate on the main problems: illegality and counternarcotics; money and corruption; disrespect for state frontiers; and finally geographical and cultural implications

The subsection on illegality and counternarcotics stresses the fuelling implications of illegality. It argues that pursuing the ban of drugs with violent means only triggers more violence, as people depending on the revenue will not give in without a fight – especially the organised criminals. Secondly, illegality and counternarcotics worsen the conflict because one alienates a large section of

the population that in essence have not much to do with the conflict; the peasants. By targeting peasants, one will cause a loss of income for a large section of the population who will seek other ways to make money that – seen the economic devastation and underdevelopment in these areas – will either join militias or get involved in other black market practices or human rights abuses. The third argument is that the illegality drives up prices, so that the combat economy can buy more guns for less drugs. Closely related to this is the fourth argument; that counternarcotics have never achieved positive results as the drug trade will continue to exist, since total eradication is physically impossible.

The following subsection deals with the money, corruption and the motives to fight. The drug trade makes a lot of money because of the fact that the goods are banned – as mentioned in subsection one. Then the first argument is that drug money is perfectly suitable for a combat economy; it makes a lot of money and law enforcement capability is weak. Secondly there is widespread corruption that undermines the prospect of peace as it prevents the creation of accountable institutions. However, the corruption can also function as a contemporary appeaser, since the taxation of the drug trade can keep all sides happy. The third argument how drug money can make the conflict worse is because it fosters alliances between organised crime and political insurgents – the shadow and combat economy. This cooperation can look like an alliance, the incorporation of tactics, or result in a hybrid; a violent armed actor that pursues both the money and the political power.

The third subsection attends the transnational potential. One of the causes for the international dimension is the relative ease with which borders are crossed by smugglers. The massive corruption, and rough geography make – next to the physical devastation the conflict brings with itself – that borders cannot be effectively sealed. Secondly, the drug trade is international as such, as drug flows cross the entire globe, from supply to demand countries. Finally, this border crossing of the drug trade caused politicians to declare the drug trade an international problem. Hence, third party states now actively engage in counternarcotics, further fuelling the conflict.

The final section is not so much as a mechanism for conflict, but it is too important to be overlooked. The role of geography, history and culture. Geographical features are so obvious that they tend to be overlooked. Le Billon offers a typology on the importance of geographical features and climate. History and culture matter, as conflict resolution can only be effective when hearts and minds of population are won. Thus it is important to understand whether the population might have a very lenient attitude towards drugs because of cultural affection. Also, via culture one can understand the population’s attitude towards drug gangs – in some cases, drug gangs take better care of the population than the government. Finally, drug routes can be built upon cultural and historical ties, such as language or ethnicity.

Illegality & Counternarcotics

Contemporary literature on natural resources and civil war understates the implications of illegality. Although it is shortly touched upon, what it merely says is that the illegality will prevent governments from engaging in drug trade, because otherwise it faces boycotts from the international community.60 Not that this is not true – although some governments are prepared to face the international sanctions for some reason – but it does not tell the whole story. The implications of illegality go far beyond this assessment made by Ross. The label of illegality is where most trouble starts. It gives the justification to pursue drug producers and traffickers with violent means – who will shoot back if they can. Unrestricted counternarcotics policies also make collateral damage in terms of civilians; these people are alienated from the central government. Moreover, counternarcotics cause the prices of a contraband to rise, meaning that in the end, it makes no difference. Fourthly, current aggressive counternarcotics programs seem absurd, as they never have achieved any concrete results in terms of reduction of drug supply and the fundamental assumption is that counternarcotics will not be able to shut down the global drug market, as mentioned in the former chapter.

Illegality as root cause of violence

First of all, the illegality is what gives the drug trade its violent potential. The illegality is put in place by international agreement, with the 1961 UN Convention on Narcotic Drugs as fundament.61 The idea is that all governments who have signed up to this, will implement and enforce these laws in their domestic system. Thus anyone producing, trafficking and – albeit to a lesser extent – consuming these “psychoactive substances” risks being penalised. The signing of an international agreement serves as a tool of the international community to press the government in to repressive policies, otherwise it runs the risk of facing international sanctions.62 Thus any government, theory goes, will punish those trading drugs and certainly not engage in trading itself.

As always, reality looks slightly more complex than the theoretical line of arguing as presented above. In a country with political unrest – remember the implications when the monopoly on violence is lacking – it is difficult to impossible to effectively maintain drug prohibition. So what will happen is that insurgents can profit from the revenue produced by drug trade as they are not effectively controlled by the government or under pressure of the international community. The government – in theory – cannot profit. This gives insurgents a natural economic advantage. What can the government do? Snyder argues that the government can opt to profit from the revenue by engaging directly or indirectly – via trade or taxing or bribery – in the drug trade. This engagement in drug trade at least diminishes the advantage of the rebels, as the government now also profits. However, direct engagement is followed by an unhappy international community, who will probably react with angry letters and economic sanctions. Government corruption also has its downsides as it has the potential to undermine the central regime. An alternative option to engagement in drug trade is actively pursuing drug producers, which is what the international community demands from

you. In areas where government control is weak, these counternarcotics efforts are likely to be met with armed resistance. Thus the law enforcement is likely to result in an escalation of violence.

What should become clear from this story and Snyders argument are two particular points: at first, exercising counternarcotics in politically instable areas is likely to result in more violence. It opens another front. Counternarcotics takes the shape of large military operations with the involvement of hard material – guns, tanks, planes, chemicals. This violence is met with violence of equal proportion. This will lead to an intensification of one of the two sides in order to try to defeat the opponent – if one of the two is really interested in ending the conflict, depending on the economic benefit of course. Another lesson from Snyder is that international drug bans can serve as a political tool for the governments. Governments are engaged in a game with the population on one side, and the international community on the other. What will eventually determine the position of the government – assuming that they have no moral objections against drug trade and act rational – is what will achieve the greatest benefits in terms of power or money. The population can give public support when the drug trade is accepted – as has happened in Afghanistan63 and Burma.64 Whereas the international community can send financial or material aid in exchange for pledges that counternarcotics will happen. Negative sanctions such as economic boycotts can also be applied, but history has shown that sticks are seldom effective.

The rapid and borderless escalation of violence as a result of intensified law enforcement measures and international involvement can be witnessed on the American continent. The US’ “War on Drugs” has had significant effects on the levels of violence in Colombia and Mexico. In Mexico counternarcotics is a task assigned to the armed forces, meaning bigger guns and heavy armour in large scale operations.65 Sitting and watching government forces destroying your business is simply not an option. Thus, as a Mexican drug lord, you will meet violence with violence.

Intended & Unintended Targets

Another important question one should ask when looking at illegality and counternarcotics is who you target. Thus far, counternarcotics is often part of the tactics to undermine the financial base of the opposing warring factions – such as the Taliban in Afghanistan or the United Wa State Army, UWSA in Burma – or destroy the business of organised crime. Yet Goodhand’s analysis on the stakeholders of the drug trade shows that probably the largest number of people that will feel the consequences of counternarcotics are not part of armed groups; the farmers or other coping strategic jobs. However, just like the opposing political factions or organised crime, these ordinary civilians will not be too happy when they find out that they’re crops are destroyed.

This is problematic in several ways. The main point is that you take away the economic base of normal people that often live in areas of the world where alternative ways of making money are scarce. So how would someone react in such circumstances? This is not always up to the individual if the opium that was intended to be sold was part of a local debt relief plan, as commonly happens in

Afghanistan or Burma.66 The consequence is often forced labour or slavery, either by the farmer itself or it has sold one of its children – usually the daughters.67 Another option is to join armed forces for a soldiers salary. Another important consequence that diminishes the chance for sustainable conflict resolution is that one alienates these people politically.

This is exactly what Raphy Favre illustrates when quoting the Taliban’s leader Mullah Omar when he gives a summary of the Taliban’s reasons to tolerate the opium cultivation in Afghanistan:

The Taleban (sic) was a grass-root movement [...] and the members understood, better than any other previous rulers in Afghanistan, the social structures in rural areas. [H]aving established strong relations at the grass-root level, the Taleban controlled their territory effectively [...] The Taleban seemed to have focussed on territorial gain and considered opium production a secondary issue. The Taleban position was summarized by Mollah Omar (editor: the Taliban leader) in an interview in which he explained that, in the long run, the Taleban would eliminate opium production in Afghanistan but that it would have to be a gradual process, as farmers depending on opium cultivation could not be deprived of their income within a year.68

Driving up prices

As was stated in the paragraph on the definition of drugs, the illegality has profound effects on the prices.69 Through an increased risk and the inclusion of bribes in the price of the end product, the price rises exponentially. The irony of counternarcotics is that, when applied in the “right” proportion it makes drugs even more profitable. Rubin and Sherman point out that eradication leads to scarcity, and scarcity leads to an effectual drive up of the price.70 So for less drugs, one can buy more weapons for instance. It is equally ironic to portray the other side of the coin; that an abundance in drugs actually undermines its price and therefore becomes less attractive as a war or shadow economy. But the price is driven up in another way too; increased counternarcotics mean an increase in risk. This results in people wanting higher pay offs, fostering corruption.71 Moreover, the large sections of organised crime that are still not caught, are in effect not worse off, since they make an equal amount of money with less drugs sold.72 The only thing that increases is the chance of getting caught, but the effect of this on the drug trade or conflict is marginal. First of all, because chances of getting caught remain close to zero, due to the creativity and innovation of drug lords and smugglers. Secondly, for the overall situation it does not matter because the revenue of the drug trade is lucrative to an extent that there will always be plenty of risk takers who are prepared to jump in, especially in economically underdeveloped areas.

The case of corruption becomes evident looking at Mexico. As stated before, the army took over the counternarcotics tasks from the police. This was done in order to counter the corruption in the police

forces – who often sold on confiscated contraband. The result of the shift of competences to the army was that now the army is also corrupt.73

Question the effectiveness

Finally, it is disputable whether counternarcotics have any effect. Recently criticism on the ‘war on drugs’ or comparable strategies has increased, and the US government has indicated to critically evaluate their policies in Afghanistan and the Andean region. Despite intensified eradication methods in Afghanistan, the country is still the world’s largest opium producer by far.74 At the start of this century, the efforts to counter the cocaine industry intensified drastically, but so did the output of cocaine.75 Furthermore, the concentration of drug trade in a single country such as Afghanistan or Colombia depends largely on the drug policies of neighbouring countries. Remember the example of counternarcotics policies in Thailand that caused the producers to move over the border into neighbouring Burma.76 The rise of Colombian cocaine follows a similar pattern; effective prohibition in Bolivia and Peru resulted in a shift towards Colombia.77

Having said that, there are cases where effective drug bans have been in place, but they have not proved sustainable. Afghanistan and Burma have proved that extreme repressive regimes have been able to effectively suppress the opium output. However, in case of Afghanistan the prohibition only lasted for a year – then the ISAF forces intervened and the opium trade increased massively. Currently, Burma threatens to slide back into the drug trade with an increase in opium output since the last year. Important explanatory factors are the earlier mentioned local credit systems – peasants will try to harvest more crops when last years crop was banned in order to compensate for the financial loss as a result of eradication. In extension of this line or reasoning lies the argument that in some cases the drug trade has become socially embedded in cultures. This makes counternarcotics no matter of simply implementing policies, wait until it does its job, and the country is done. Emotions will come into play and further complicate matters. Secondly, there is the question of sustainable alternatives. As indicated in the former point, successfully decreasing the drug trade is a matter of years, perhaps more. This means that a gradual shift to another economy is required instead of rapid change. Unfortunately though, success stories on sustainable alternatives have been very limited and absent is massive drug producers such as Afghanistan or Burma. In Burma, the alternative that was offered was the rubber industry, but this is not sustainable as reports indicate.78

The explanation for the ineffectiveness is because conflicts and drug markets are dynamic and ever changing. It is very hard to measure how effective aggressive policies are; in some cases they indeed do lead to a reduction of output in drugs. Last year, the output of Afghan opium decreased for the first time since the opium ban of 2001 was lifted. The UNODC claims the credits.79 However, this decrease in Afghan opium is accompanied by an increase in Burma’s opium output – the balloon

effect. Another explanation is because consumer demand for heroine in Western countries could have dropped. Finally, the decrease in opium output in Burma was accompanied by a surge in the production of ATS, such as crystal meth. This trend is also seen in present day Mexico; explained from successful law enforcement in the US which causes ATS labs to move down south plus a decrease in demand for other drugs.80

So when reading the optimistic quotes from the UNODC in their annual drug survey about the drop in drug output, question first of all whether it is true – and how do they know that – and secondly, whether there might be alternative explanations except for the action of the UN – remember that the revenue of the drug trade is astronomical compared to the funds the UNODC has in order to pursue their program. Finally, is an output in opium revenue paired with an increase in other drugs such as chemicals? Or is a decrease in 2009 followed by increases in 2010?

Conclusion

So how do illegality and counternarcotics cause the conflict to escalate? First of all, counternarcotics is pursued with violent means and then the ball starts rolling; violence is met with more violence and so on. Assigning the military with counternarcotics tasks is a declaration of war that has destructive consequences. Secondly, the target groups of counternarcotics are warlords and organised crime, but one also unintentionally targets the civilians. Civilians matter for the sake of long term, sustainable peace. Various governments have tolerated drug production because of the financial benefits and the public support that it generates. The third point that was touched upon is the fact that basic economics states that eradication leads to scarcity, which can lead to increasing profits. This means more bang for less fix – assumed that the money is intended to buy weapons. Finally, global prohibition has not lead to a sustainable decrease in overall drugs on the globe – so it will stay a financial source for political unrest forever.

Money, Corruption and Motives

This section pays special attention to one of the key factors that complicates the prospect of peace: money. A typical Political Economist asks the question where money and power can be separated – if possible at all. This is no exception. The use of bribes, personal connections, double agendas are the features that make the problems of drug funded wars so complex.

However the first paragraph focuses on a relatively easy and obvious connection between the drug trade and armed conflict. Namely that the revenues of the drug trade are an ideal base to build a combat economy on. It currently does, and has done so in the past. Following this, the importance of personal connections is explained by focussing on the corruptive power of money. Human beings have been proven weak creatures when it comes to resisting large amounts of money. In armed conflicts and politically instable surroundings this is no exception. What results is a lot of corruption – especially when the conflict has powerful stakeholders in the international arena who send more money to support their proxy armies. It hinders the prospects of peace, as people generate an interest in war and because accountable institutions seem far away. Finally, this corruptive power

can affect the motives of armed groups – political militias can become tempted by the money and thus will protect the status quo of violence in order to assure the influx of money. How do you approach a militia that does not want to lay down their arms because keeping on fighting is more lucrative? Besides, who do you target when an organisation has no leader?

Combat Economy

An often heard argument to engage in counternarcotics is to undermine the financial base of the insurgents – think of Afghanistan or Colombia, where the Taliban and the FARC have used the money to buy material and recruit combatants. This is probably the most obvious link on how drugs are linked to conflict; the revenue of the illegal good, taxed and sold by insurgents, is used to strengthen the financial base of these insurgents. This is in conformity with Goodhand’s description of the combat economy: “the production, mobilization and allocation of economic resources to sustain a conflict and economic strategies of war aimed at the deliberate disempowerment of specific groups”.81 Before moving to examples, it should be clarified that the drug trade is not the only industry that insurgents’ profits come from. The extraction of other natural resources, engaging in other black market activities – arms trade, prostitution, slavery – or foreign financial support and money laundering are other options that are exploited by different insurgent groups.

Examples the drug trade as combat economy are to be found everywhere. Goodhand’s theory is based on a description of Afghanistan, where the Taliban and other groups – such as the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan – are engaged in drug trade.82 In Burma, the money derived from opium trade is invested in the community, which also includes the defence force.83 Burma experiences other natural resources extraction, such as illegal mining or illegal logging.84 The Golden Triangle experienced drug funded insurgencies already several decades ago when the area was plagued by conflicts. The Kuomintang – the defeated Chinese nationalist forces from the Civil War – fled to Burma, bringing heroin trade actively into the region.85 But also the aftermath of French colonialism and the subsequent American invasion in Vietnam fostered the heroin trade.86 Guáqueta observes that together with extortion and kidnapping, the drug trade presents the greatest opportunity for insurgents to get their money and continue to battle.87

So far, only drug producing countries were mentioned. Transit countries that are placed on the route of supply to demand – Afghanistan to Western Europe for example – can also experience drug trade and armed conflict. The presence of warlords in uncontrolled areas means that either organised crime groups have to pay taxes to the local rulers, or that they take over the contraband themselves. One can think of the anarchy caused by violence during the Kosovo conflicts. The Kosovo Liberation Army – KLA – depended partly on the revenue of the illegal drug trade88, especially heroin from

Afghanistan destined for the European market. Mexico is a special case of a production and transit country. It gained importance when Colombian cocaine went overland into its biggest consumer, the US. The money of the drug trade is used to further undermine the central government. Another example of a transit area is West-Africa. Presently, Guinea-Bissau is the most notorious, but shady governments in Liberia and Sierra-Leone also profited from the drug industry.89

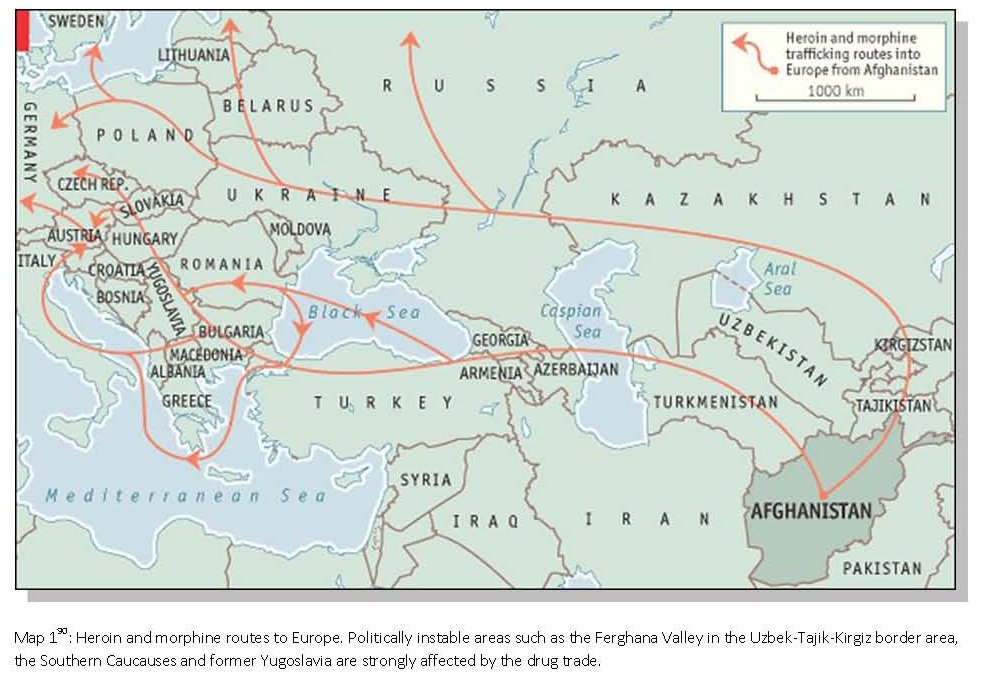

Map 190: Heroin and morphine routes to Europe. Politically instable areas such as the Ferghana Valley in the Uzbek-Tajik-Kirgiz border area, the Southern Caucauses and former Yugoslavia are strongly affected by the drug trade.

Corruption

Apart from buying weapons, the revenues of drugs are extremely useful in bribery cases. In the literature, synonyms such as ‘taxes’ or ‘tributes’ are also applied to describe corruption. So what is corruption and how can corruption contribute to the conflict? Before continuing, it is worth reminding once again that, although prices vary, a kilo of pure cocaine or heroine equals annual salaries in the countries investigated.

Corruption in this case means that actor A gives a financial tribute to actor B in return for a service. Actor A can be anyone, and in this case it is often a stakeholder in the drug industry; peasants, criminals, insurgents. Actor B is the de facto ruler of the land, so the government or some local strongman. Actor B can have different motives for the corruption; sheer self enrichment, or using the money for some cause. The service can mean several things, but in general the money is paid for protection or silence. What it demonstrates is that interpersonal relationships can be very important in conflicts such as these.