|

RECREATIONAL CANNABIS

Based On a report filed in 1972 by the Baan commission (www.drugtext .org/library/reports), the Dutch Opium Act on Illicit Drugs of 1976 brought a clear-cut distinction between drug users and traffickers. At the same time, a distinction was introduced between illegal drugs with so-called unacceptable health risks (all other illicit drugs) and cannabis products by means of a de-penalization of the latter. The main goal was to create a separation of markets, preventing hard drug use and addiction.

A policy was developed permitting the retail trade of cannabis products in about 1,500 so-called coffee shops under specific conditions through a system of prosecution guidelines called AHOJ-G: A = no advertisement or public display of products, etc.; H = no hard drugs (meaning all illegal drugs but cannabis); 0 = no nuisance and/or disturbance of public order; J = no sale to minors (anyone under 18 years of age); G = no wholesale (a maximum of 5 grams per transaction) and the involvement of the so-called Triangle Committee (mayor, chief of police, and district attorney.) Although now, some thirty years later, as cannabis is by far the most commonly used illicit drug in the Western world, only in the Netherlands can one freely buy cannabis products in these cannabis retail facilities called coffee shops.

The cannabis products sold in these coffee shops are hashish (cannabis product) and marijuana (dried parts of the cannabis plant). Most of the hashish sold is imported from Morocco, but the vast majority of cannabis products sold in the coffee shops consists of so-called Nederweed.

This Nederweed, marijuana grown in the Netherlands, is produced both on a small scale and on a larger scale in a semiprofessional way. Although the retail trade of hashish and marijuana in the coffee shops is tolerated, no similar systems are applied toward the wholesale trade or production and growing of cannabis in the Netherlands.

In 1994, when Dutch marijuana started to become more dominant on the Dutch market, the Netherlands Institute for Alcohol and Drugs, where I was employed at the time, was concerned that the production of this marijuana would fall into the hands of organized crime. A law was proposed to regulate the Dutch cannabis market (www.drugtext.org/library/articles/ lexlap.html). This proposal did not pass Parliament, and the prosecution of Dutch cannabis production has since become a high priority for the Dutch police, with foreseeable results.

Today we may conclude that the intensified judicial attention on the supplying of coffee shops has pushed the coffee shops toward more criminal circles. These judicial interventions disturb the normalized supply patterns and recently even caused undesirable price increases ("The Czar's Reefer Madness," New York Times, August 26, 2006). A large number of coffee shops offer resistance to this drift toward a more criminal existence; the proprietors of these coffee shops would prefer a normal legal status with corresponding taxation and contributions, but the current legislation prevents this. A solution for this dilemma would be to extend the guideline system to cannabis production, but although the hypocrisy of the current situation is realized by many parties, such as city mayors, judges, and scientists, the legislators refuse to consider this option, using international treaties, pressure, and politics as an excuse. It almost seems like the Dutch legislators suffer from an amotivational syndrome concerning cannabis.

Now, to put my critical approach to Dutch cannabis policy in the right perspective, I have to emphasize that its consequences and effects are, in my view, superior to those of cannabis policies carried out elsewhere, both in Europe and especially in the United States. Hence my criticism is to be regarded from a Dutch and constructive perspective.

The following data from the Centre for Drug Research (CEDRO, a department of the School of Environmental Sciences at the University of Amsterdam) and the EMCDDA clarifies this position (from "Cannabis: The Changing Picture of Cannabis Use in Europe, 2007, European Monitoring Centre on Drugs and Drug Addiction," www.emcdda.europa/ eu/publications/online/ar2007/en/cannabis.

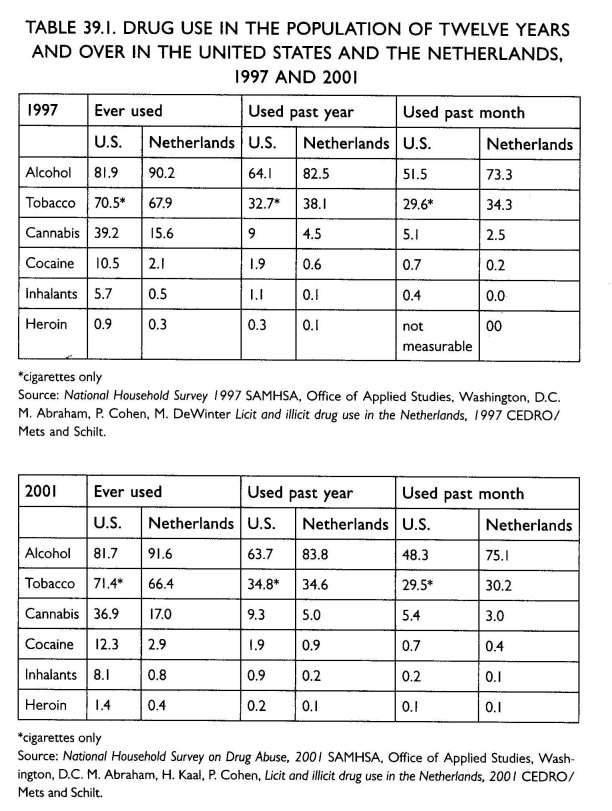

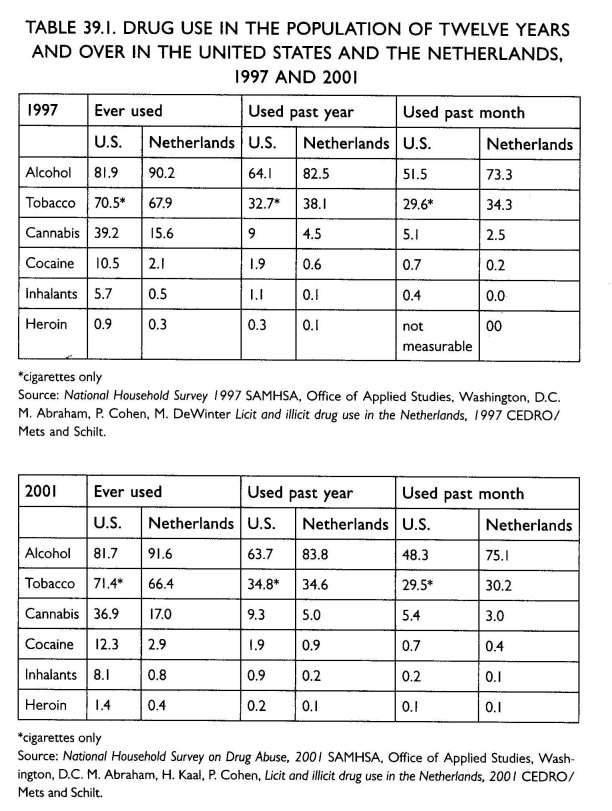

Table 39.1 clearly shows that Dutch cannabis use was and is lower than American cannabis use.

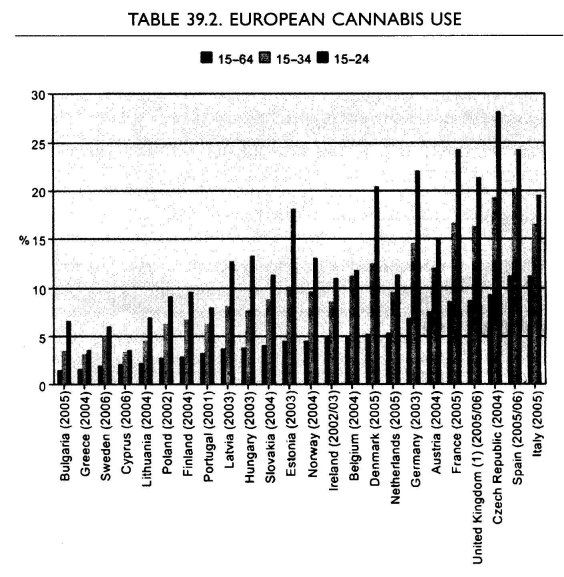

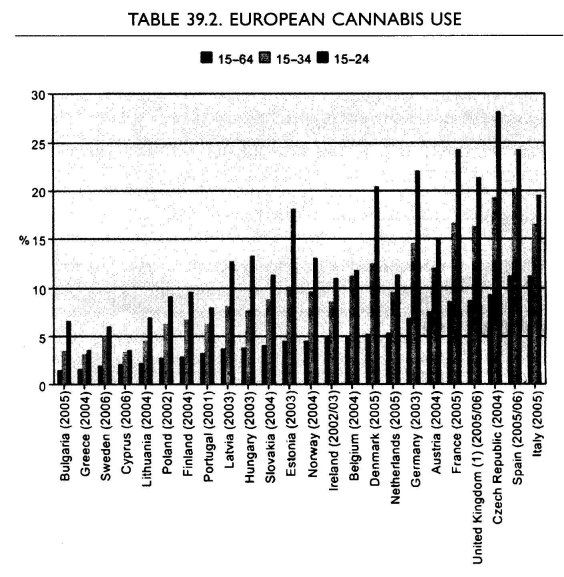

Table 39.2 gives us a picture of European cannabis use, showing Dutch cannabis use was in the mid-range in 2005 and considerably lower than, for example, French cannabis use where French cannabis policy is far more repressive.

Before I move to medicinal cannabis, let me conclude this section on recreational cannabis by briefly discussing two recent issues in the Netherlands and the lack of new realistic prevention efforts.

The Christian Democrat mayor of the city of Maastricht, Gerd Leers, has recently announced the move of a significant number of coffee shops toward the border (Maastricht is a border town of both Belgium and Germany) to decrease the nuisance caused by large numbers of Belgian and French citizens visiting these coffee shops ("Forget Politics, Let's Rap," The Guardian, February 28, 2006; Leers: For the Regulation of Cannabis, ANP, April 26, 2006; "Belgians Afraid of Maastricht Coffeeshop Policy," ANP, June 1, 2006). He also called for the immediate regulation of production and delivery of cannabis to the Maastricht coffee shops. Whereas he faced opposition for his relocation plans only from Belgian politicians (probably for electoral reasons), his regulatory plans were greeted positively by a majority in Dutch Parliament but were swiftly denied by the minister of justice from the same Christian Democrat party.

As almost everywhere else in the world, drug policy in the Netherlands is rarely based on empirical studies or cost-benefit analyses. Many decisions are based on political opportunism, innuendo, and populism. Bearing this in mind is the only way to understand the recent political decisions concerning coffee shops in the near vicinity of schools ("Coffeeshops in the Vicinity of Schools: A Real or Political Problem?" TNI, May 31, 2007).

Not based on any scientific or other data, and without even examining the possible consequences of such proposals for cannabis availability and consumption, or the influence on the main goal of cannabis police—the separation of markets—a decision was made to set minimum distances between coffee shops and schools. This, while no policy whatsoever is in place for what is in my view the main public health problem with cannabis consumption in the Netherlands as well as the rest of Europe.

Cannabis in Europe is mostly consumed in so-called joints. These joints consist of 80 to 90 percent tobacco with some cannabis or hashish mixed in. In fact, many youngsters' first tobacco consumption is by means of these joints. Now at the age of, for example, thirty, most of these youngsters have stopped consuming cannabis but have ended up with a significant tobacco addiction.

Therefore, for many years now, I have suggested a prevention campaign informing young people of the hazards of the above form of cannabis use and of alternative ways of consumption (pure cannabis joints and/or with tobacco replacements). Recent Swiss scientific research has revealed further negative aspects of combined cannabis-tobacco use (Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine 2007, 161 (11): 1-42-1047), but realistic Dutch government prevention efforts concerning such use are nonexistent (Tips for Cannabis Consumers, www.drugtext.org/sub/tips.htm).

MEDICINAL CANNABIS

Thanks to the health minister at that time, Dr. Els Borst, patients in the Netherlands can obtain fully legal medicinal cannabis by prescription from pharmacies since September 1, 2003. This cannabis is produced under control of the Government Bureau of Medicinal Cannabis (BMC) and consists of three varieties of cannabis. Medicinal cannabis is prescribed to a wide variety of patients, such as people suffering from AIDS/HIV; multiple sclerosis and other muscle-related diseases; Tourette's syndrome; rheumatism; and cancer ("The Future of Legal Medicinal Cannabis," quickscan by the Ministry of Health, December 2004).

Recently, Germany, Italy, and Finland have also decided to enable the prescription of such medicinal cannabis and to facilitate such practice on the basis of cannabis imported from and produced by the BMC in the Netherlands ("Dutch Medicinal Marijuana Imported by Germany, Italy, and Finland," ANP, August 22, 2009). Additional countries are expected to follow in the near future.

The main problem with medicinal cannabis in the first years was the availability of more varieties of cannabis at a much lower price in the coffee shops, but now more varieties are prescribed, and significant price cuts have been realized; more patients and doctors have realized the advantages of cannabis produced for medicinal purposes, and hence of consistent quality and constant strength (October 13, 2009, De Volkskrant, Cannabis as medicine).

The current Dutch minister of public health, welfare and sport, Ab Klink, has just decided that the production and prescription of medicinal cannabis will be extended for at least another seven years. Further scientific studies are also being facilitated.

|