Brain aging in a sample of normal Egyptians cognition, education, addiction and smoking

Drug Abuse

Journal of Neurological Sciences 148 (1997) 79-86

JOSJRNAL OF THE

NEUROLOGICAL SCIENCES

Brain aging in a sample of normal Egyptians cognition, education,

addiction and smoking

Osamah Elwana'*, Azza Abbas Helmy Hassana, Maged Abdel Naseera, Fadia Elwanh, Randa Deifa,

Omar El Serafya, Eman El Eanhawya, Medhat El Fatatry`

'Department of Neurology, Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt

`'Department of Clinical Psychology, Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt

`Department of General Medicine, Cairo University. Cairo, Egypt

Received 20 May 1996; revised 7 November 1996; accepted 24 November 1996

Abstract

The impact of duration of education, cannabis addiction and smoking on cognition and brain aging is studied in 211 normal Egyptian volunteers with mean age 46.4±3.6 years (range: 20-76 years). Subjects were classified into two groups: Gr I (non-addicts) with 174 subjects- mean age 49.9--3.8 years (range 20-76 years), smokers and non-smokers, educated and non-educated and Gr If (cannabis addicts) with 37 subjects, mean age 43.6±2.6 years (range 20-72 years) all smokers, educated and non-educated. Outcome measures included the Paced Auditory Serial Addition test (PASAT) for testing attention and the Trailmaking test A, and B (TMa and TMb) for testing psychomotor performance. Age correlated positively with score of Trailmaking test (TMb) in the non-addict group and in the addict group (TMa and TMb). Years of education correlated negatively with scores of Traalmaking test (TMb) in the non-addict group (Gr 1) but not the addict group (Gr II). However, in both groups mean scores of the Trailmaking test (TMa) were significantly lower in subjects with a primary level of education than those with higher levels of education. No significant difference was detected between male smokers and nonsmokers of Gr I (non-addicts) regarding any of the neuropsychological tests. Yet, smokers and the non-educated group had poorer attention compared to non-smokers of the same group. Cannabis addicts (Gr II) had significantly poorer attention than non-addict normal volunteers (Gr I). It is concluded that impairment of psychomotor performance is age related whether in normal non-addicts or in cannabis addicts. A decline in attention was detected in cannabis addicts and has been considered a feature of pathological aging. Education in early life as well as the duration of education are neuroprotectors for brain aging more so in the non-addict than addict group. Though cigarette smoking per se has no effect on cognitive abilities in normal aging, it becomes evident that its association with lack of education impairs attention. © 1997 Elsevier Science BY Drug Abuse & Addiction, Detoxification, Treatment, Opiate Withdrawal. Substance Abuse: Heroin, Cocaine, Marijuana, Crystal meth, Vicodin, OxyContin, Amphetamines, Percocet and others.

All Rights Reserved.

Keywords: Normal brain aging; Cognitive functions; Education; Addiction: Smoking

1. Introduction

The recent interest in aging is attributed to the remarkable increase in the number of elderly persons throughout the world. Whereas age per se has been denied as a factor in intellectual deterioration where cognitive abilities remain generally stable throughout adult life (Wilkie and Eisdorfer, 1971) yet, after the age of 60 years, a minority

*Corresponding author. 30 Adly St.. Cairo, Egypt. Tel. +20 2 3407816 (home), -20 2 3927524 (office); fax: +20 2 3031823.

of people show cognitive decline which becomes more evident in the 9th decade (Schaie, 1990). On the other hand, a definite decline of cognitive functions with aging was frequently stressed (Horn, 1975; Botwinik, 1977; Busse, 1987; Moehle and Long, 1989; Morley et al., 1992).

Elwan et al. (1996) in a study of brain aging in normal Egyptians revealed a decline in cognitive functions with aging particularly in those with vascular risk factors, as well as non-educated normal volunteers.

Zhang et al. (1990) reported increased prevalence of

0022-510X197/$17.00 © 1997 Elsevier Science BY Drug Abuse & Addiction, Detoxification, Treatment, Opiate Withdrawal. Substance Abuse: Heroin, Cocaine, Marijuana, Crystal meth, Vicodin, OxyContin, Amphetamines, Percocet and others.

All Rights Reserved. All rights reserved PIlS0022-510X(96)05336-1

dementia among elderly Shanghai Chinese residents where it occurred in 18% in non-educated as compared to 4% in those having more than 6 years of education. Similar findings have been found in Italy (Bonaiuto et al., 1990) and Canada (D'Arcy, 1994). Moreover, in developing countries, cognitive difficulties were reported in non-educated subjects as in Senegal (Greenfield and Bruner, 1966), South Africa (Page, 1973), and Morocco (Wagner, 1978).

Acute use of marijuana impaired learning, associative processes, and psychomotor performance (Block et al., 1992) whereas chronic heavy use was associated with deficits in mathematical skills, verbal expression, and memory retrieval (Block and Ghoneim, 1993). Amir and Bahri (1994) detected impairment of visuographic functions in the Arabian Gulf population due to substance abuse (alcohol, polydrug, and heroin), a finding consistent with reports for European and American communities. On the other hand, several studies reported no differences in cognitive functioning on a large battery of neuropsychological tests between marijuana users and controls in Jamaica (Bowman and Pihl, 1973) and Costa Rica (Satz et al., 1976). Soueif (1971) found that Egyptian cannabis users were slower learners than controls and did significantly worse on objective tests of mental performance. It was estimated that hashish use in Egypt was 11.44% in males working in the manufacturing industries (Soueif et al., 1988), 5.05%o in secondary school males, and 8.79% in university student males (Soueif et al., 1990).

Many studies of the effects of cigarette smoking have shown a nicotine-induced enhancement of attentional efficiency (Frankenhaeuser et al., 1971; Heimstra et al., 1967). Wesnes and Warburton (1978) found that cigarette smokers performed more efficiently than non-smokers in neuropsychological testing for attention. However, a significant increase in brain atrophy was revealed on CT scan of chronic smokers when compared to non-smokers indicating that chronic smoking exaggerated age-related brain atrophy (Kubota et al., 1987).

The goal of the present work is to study brain aging in a larger sample of normal Egyptians with the aim of evaluating the impact of duration of education, addiction and/or smoking on cognition and brain aging.

2. Materials and methods 2.1. Subjects

This study included 211 normal independent volunteers (166 males, 45 females), either relatives of patients, personnel working in Kasr El Aini Hospital or referred to an outpatient clinic for routine medical check-up. Their age ranged from 20 to 76 years with a mean of 46.4±3.6 years. Whereas 77 subjects were of limited literacy and were considered non-educated (as they could just read, write, and make simple calculations but had not had the 6 years

of compulsory formal primary education), 134 subjects were of different educational levels and were divided into three categories: (1) primary school level (completed the 6 years of compulsory education), (2) high school level (6-12 years of preparatory and secondary school education) and (3) college or professional school graduate (more than 12 years of education). Exclusion criteria were: (a) score less than 70 on the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised (WAIS-R) (Wechsler, 1981) (b) score less than 24 on the Minimental State Examination (MM SE) (Folstein et al., 1975); (c) history of neurological or psychiatric illness; (d) disorders of communication. Subjects of the present study were classified into two groups; Group I: including 174 normal volunteers with and without vascular risk factors and/or either cigarette smokers or non-smokers and Group 11: including 37 males with cannabis addiction and with or without vascular risk factors. Subjects of Group 11 have been using cannabis regularly for at least 6 years and they were all cigarette smokers. Vascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, hyperuricemia were reported in 44 subjects (28 in Group I and 16 in Group II). All subjects gave informed consent to participate in the study.

2.2. Methods

All subjects undertook:

1. Thorough clinical neuropsychiatric and medical examination;

2. Laboratory tests detecting risk factors:

3. Neuropsychological assessment using a battery for evaluation of specific cognitive functions which included: (a) the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test `PASAT' (Gronwall, 1977) for testing ATTENTION and (b) the Trailmaking test A. B `TMa and Thlb' (Reitan, 1969) for PSYCHOMOTOR PERFORMANCE.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done using a Mackintosh Plus computer and Stat-view statistical package. The unpaired t-test was used for comparing means of two groups and the correlation coefficient (r) to determine the correlation between two parameters.

3. Results

Of the 174 subjects of Group 1, 129 subjects (74.15r) were males and the remaining 45 subjects (25.9%) were female, ranging in age from 20 to 76 years with a mean of 49.1±3.8 years. Group 11 consisted of 37 males of age

81

rang. 20-72 years and a mean of 43.6±2.6 years. Subjects of both groups were classified according to age into three groups: Group A of young age (20-39 years): 61 subjects (51 Group I and 10 Group II), Group B of middle age (40-59 years): 73 subjects (59 Group I and 14 Group II) and Group C of old age (60 years and above): 77 subjects (64 Group I and 13 Group II). Seventy-seven subjects (70 of Group I and 7 of Group II) were non-educated and represented 36.5% of the whole sample. The remaining 134 educated subjects (63.5%) (104 of Group I, 30 of Group II) included different levels of education belonging to Category 1 (primary school) 54 subjects (42 Group I and 12 Group II), Category 2 (high school) 45 subjects (35 Group I and 10 Group 11) and Category 3 (college graduate) 35 subjects (27 Group I and 8 Group 1I). The mean years of education was 6.1±3.96 and 6.9±3.4 years in Group I and Group II, respectively. Sixty subjects from Group I were cigarette smokers and 114 subjects were non-smokers. All smokers of Group I were males due to rarity of habit of cigarette smoking among Egyptian females especially in low socio-economic and rural areas. Vascular risk factors other than smoking - were present in 44 subjects (20.8%) (28 of Group 1, 16 of Group II). Table 1 summarizes the demographic data of the sample submitted for this study.

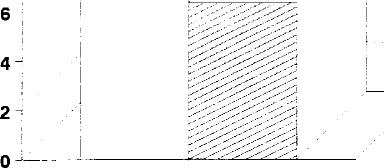

In Group I subjects (non-addicts), a statistically significant correlation was generally found between age and Trailmaking test B (TMb) scores (Fig. 1, Table 2) indicating deterioration of psychomotor performance with advance in age. The more the years of education, the less were the scores of the Trailmaking B test (TMb) meaning better psychomotor performance with increase in the duration of education (Fig. 2, Table 2). Old age subjects (60 \ ears and above) and subjects with risk factors demonstrated significant worsening in psychomotor performance (TMb and TMa respectively) when compared to

Table I

Demographic information of Group I (non-addicts) and Group II (addicts)

|

Group I |

Group II |

|||

|

Males |

Females |

Total |

||

|

Age group: |

129 |

45 |

174 |

37 |

|

(A) 20-39 years |

51 |

- |

51 |

10 |

|

(B) i0-59 years |

36 |

23 |

59 |

14 |

|

(C) :>60 years |

42 |

22 |

64 |

13 |

|

Non-educated |

36 |

34 |

70 |

7 |

|

Educated: |

93 |

11 |

104 |

30 |

|

(1) up to 6 years |

33 |

9 |

42 |

12 |

|

(2) 6-12 years |

33 |

2 |

35 |

10 |

|

(3) >12 years |

27 |

- |

27 |

8 |

|

Smokers |

60 |

b |

60 |

37 |

|

Non-smokers |

69 |

45 |

114 |

|

|

With n,k factors |

19 |

9 |

28 |

16 |

|

No risk factors |

110 |

36 |

146 |

21 |

'Hieh education attainment is not common among Egyptian females from low social level and rural areas.

°Cigarette smoking is not a habit among Egyptian females.

rJu1ck YI0t

•

65-1

fi al

0

10 00 0

43: 00 0 ------------------------------------------

ae 1054

Fig. l. Correlation between age of non-addicts (Group I) and scores of Trailmaking test B (TMB).

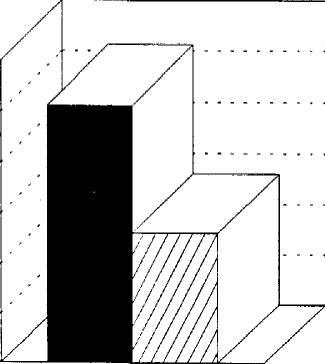

those of middle age (40-59 years) and those having no risk factors (Fig. 3A,B). There was no significant difference in psychomotor performance (TMa, TMb) between smokers and non-smokers. Regarding attention, no correlation could be detected between age or years of education and PASAT scores in subjects of Group I as a whole (Table 2). However, females of Group I showed worse attention on PASAT when compared with males (Fig. 4). Though no statistically significant difference was detected between smokers and non-smokers - of males of Group I as a whole - in PASAT, smokers of the non-educated group had worse PASAT scores when compared to nonsmokers. Such a difference could not be found in the educated group (Table 3).

Group 11 subjects (addicts) showed significant correlation between age and scores of Trailmaking A and B tests (TMa and TMb) meaning impairment of psychomotor performance in addicts with increase of age (Fig. 5A,B, Table 2). No correlation was found between age and PASAT scores of attention or between duration of education and scores of neuropsychological tests applied (Table 2).

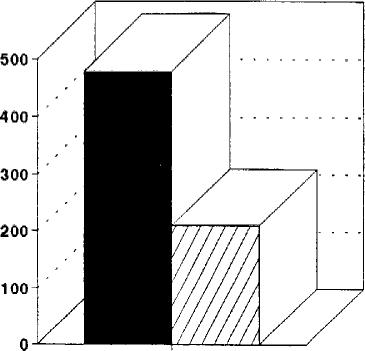

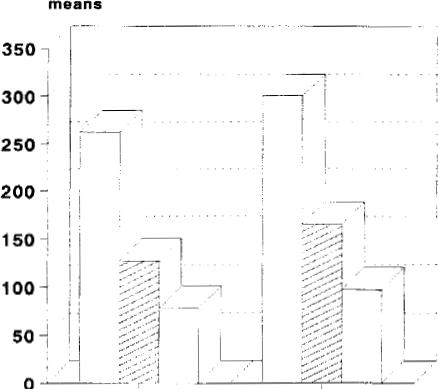

Both Group I and Group II demonstrated that subjects with primary education (category 1) had worse psychomotor performance (TMa) when compared to subjects having higher levels of education (categories 2 and 3) (Fig. 6).

Comparison between Group I and Group II revealed that addicts had significantly worse attention on PASAT than non-addict males (Table 4).

Using Anova, no statistically significant difference was detected after stratification of smokers and addicts by age and risk factors.

4. Discussion

Several factors such as age, sex, less education, occupation, and low socio-economic status have been claimed to

A E

Table 2

Correlation coefficient (r) between scores of neuropsychological tests (PASAT, TMa and TMb) and age, duration of education in Group 1, Group II subjects

|

Test data |

Group I |

GroupII |

|||

|

Age (years) |

Years of education |

Age (years) |

Years of education |

||

|

PASAT |

-0.16 |

0.29 |

-0.14 |

0.15 |

|

|

Trailmaking A (TMa) |

0.1 |

-0.18 |

0.48* |

-0.12 |

|

|

Trailmaking B (TMb) |

0.59* |

-0.44* |

0.67* |

-0.17 |

|

|

*Significant correlation (P<0.05). |

Ouitk |

Plot |

|||

-----------------------------------------

|

16;0 |

||

|

L L k' A T 1 |

||

|

0 |

||

|

0 N |

0 0 0 |

0 |

n; 000 0 0;

----------------------------------

ea 1054

TMB

Fig. 2. Correlation between years of education of non-addicts and scores of Trailmaking test B (TMB)

impair cognitive abilities in late life (Zhang et al., 1990; O'Conner et al., 1991; Stern et al.. 1994).

Brain functions - especially psychomotor performance - generally slow in the elderly (Hayslip and Panek,

060 years and above m40-59 years

Fig. 3. (A) Means±SD of Trailmaking test B in old and middle aged subjects. (B) Means-SD of Trailmaking test A in subjects with and without risk factors.

14

12-

10

-

P<0.05

MALES E FEMALES i

Fig. 4. Means±SD of PASAT in males and females of Group 1.

P<0.05

P <0.05

0with risk factors ono risk factors

83

Table 3

Means-SD of PASAT in smokers and non-smokers of males of Group I (educated and non-educated subjects)

|

Smokers |

Non-smokers |

t-value |

|||

|

Group 1: |

15.9±6.6 |

(n=60) |

13.1±7.1 |

(n=69) |

-1.6 |

|

Educ.:;ed |

15.7±6.7 |

(n=42) |

14.4±7.7 |

(n=51) |

0.35 |

|

Non-.Sucated |

10.2±8.6 |

(n=18) |

15.2±7.8 |

(n=18) |

-2.09* |

*Signili,ant difference (P<0.05).

1989). Accordingly, older adults are significantly slower than _young adults (Goggin and Meeuwsen, 1992). Elwan et al. ( 1996) revealed deterioration of psychomotor performance with advancing age in normal Egyptians, a finding that has been further verified in the present work conducted on a larger Egyptian group of addicts or nonaddict,. Moreover, elderly subjects (60 years and above) showed a greater decline than younger ones.

The impact of education on cognitive functions is controversial. Less educated people were found to perform worse on mental status tests than those with more education I \lortimer and Graves, 1993). Recently, Plassman et al. ( 1995) reported that years of education contributed significantly to cognitive status. They detected an association between education in early adult life and cognitive status in late life which may be an important factor when evaluating risk factors for cognitive decline in the elderly.

Quick Plot ------------------------------------------72; o

4Qio o -------------------------------------------

85 328

TM-A

Quick Plot

-------------------------------------------

43:o

------------------------------------------

197 590

TM-8

Fig. 5. Correlation between age of addicts (Group II) and scores of Trailmaking test A (TM-A) and B (TM-B).

Fig. 6. Means±SD of Trailmaking test A in Group I and Group II subjects with different levels of education.

Similar results have been found by Elwan et al. (1996), when subjects of limited literacy did worse than educated subjects having 6 years of compulsory formal primary education on a variety of neuropsychological tests later in life clarifying the value of education in early life on cognitive performance in the elderly. In the present study, there was better psychomotor performance with increased years of education, Moreover, subjects with higher levels of education (high school and college graduates) did better than those with primary compulsory formal education alone. Swarthout and Synk (1987) found highest positive correlation between scores of cognitive tests and education of more than 12 years. Macrae (1984) revealed no difference of cognitive abilities among secondary, technical, or university levels of education. According to the present data from the Egyptian study, it is noteworthy that the duration of education is the main contributing factor to the cognitive decline in the elderly. Greater educational attainment provides for a functional reserve of brain capacity that serves to delay the onset of cognitive impairment (Katzman, 1993). The risk of Alzheimer's disease has been claimed to be reduced by educational attainment either by decreasing the ease of clinical detection or by imparting a reserve that delays the onset of clinical manifestations (Stem et al., 1994). On the other hand, Beard et al. (1992) suggested that the apparent protective effect of education on dementia could be related to selection, measurement, and/or confounding biases.

Vascular risk factors may impair performance on a variety of cognitive tasks (Bornstein and Kelly, 1991). In

Group I

Group 11

E ]Primary school High school u College graduate

0

O

e

A

E E'

0. Elwan et al. / Journal of Neurological Sciences 148 (1997) 79-86

Table 4

Means±SD of PASAT. TMa and TMb in Group I and Group II

|

Group I (non-addicts) |

Group II (addicts) |

t-value |

||

|

PA SAT |

15.3±6.9 (n=129) |

7.3±6.5 (n=37) |

3.84* |

|

|

Trailmaking A (TMa) |

254±341 (n=60) |

292±161 |

(n=33) |

1.62 |

|

Trailmaking B (TMb) |

385±281 (n=28) |

402±226 |

(n=15) |

0.9(• |

|

*Significant difference (P<0.05). |

||||

Egyptians, subjects with risk factors had poorer psychomotor performance than subjects with no risk factors confirming previous findings (Elwan et al., 1996). Moreover, Meyer et al. (1986) found significant improvement of cognitive functions in patients with multi-infarct dementia after controlling the blood pressure and stopping cigarette smoking.

Cannabis influences many aspects of human cognition and learning (Bowman and Pihl, 1973). Impairment of attention on PASAT occurred in Egyptian hashish users when compared to normal volunteers and has been attributed to the fact that PASAT scores depend on mathematical abilities which are impaired with hashish. Marijuana impaired performance on arithmetic tests (Heishman et al., 1990), while chronic heavy marijuana use leads similarly to deficits in mathematical skills (Block and Ghoneim, 1993). Though Pope et al. (1995) found no evidence to support a prolonged or a toxic effect on CNS, they detected that cannabis can impair attention and psychomotor tests during the 12-24 h after use. Serial subtraction of sevens test - which is dependent on sustained attention - was impaired with increasing dose of cannabis (Melges et al., 1970; Dornbush and Kokkevi, 1977). Impairment with cannabis was relatively moderate in tests of sustained attention where the task is fairly simple (Rafaelsen, 1972). In the task where every step depends on the previous one - as in PASAT - the effect of cannabis was most clearly seen. In normal non-addict Egyptians in this study, attention was not influenced by aging nor years of education. Elwan et al. (1994) found that attention was impaired in cerebrovascular elderly subjects. Hence, impairment of attention has to be considered as a feature of pathological rather than normal aging.

Smoking is known to raise the general arousal and improve the ability to concentrate (Myrsten and Andersson, 1978). It is most likely that this increased arousal makes a person feel more confident in his ability to cope with the task set and thus relieved from tension and anxiety even if his actual performance might not be improved. Attentional processes are facilitated by cigarette smoking (Andersson and Hockey, 1975). This increased selectivity of attention with smoking might be subjectively interpreted by the smoker himself as an improved ability to concentrate. Conversely, no difference could be detected between smokers and non-smokers in non-addict Egyptians whether in attention or psychomotor performance. Cigaret

to smokers maintained a constant superior level of concentration compared to deprived smokers and non-smokers who both exhibited decrements in cognitive tasks (Wesnes and Warburton, 1978). Former cigarette smokers were significantly more aware than either never-smokers or smokers while never-smokers were more aware than smokers (Remer, 1992). Whereas Hill (1989) found no difference between older adult non-smokers and ex-smokers on cognitive functions, decrements were found for smokers on measures of psychomotor speed leading to the conclusion that current cigarette smoking negatively influences fast cognitive abilities.

In non-educated non-addict Egyptians, smokers shoved worse attention than non-smokers whereas such difference was not evident in educated subjects. This again supports the concept of the protective value of education on cognitive status. Though cigarette smoking per se has no effect on cognitive abilities in normal aging, it becomes evident that its association with lack of education impairs attention.

In conclusion, impairment of psychomotor performance is an age-related process whether in normal non-addicts or addicts. Decline in attention was detected in hashish addicts compared to non-addicts and has been consider: d as a feature pointing to pathological aging. Education in early life as well as the duration of education are neui oprotectors for brain aging and this is more evident in normal non-addicts than addicts. Cigarette smoking may be hazardous and may impair attention in the absence of education.

References

Amir, T. and Bahri. T. (1994) Effect of substance abuse on visuoeraphic function. Percept. Mot. Skills. 78(l): 235-241.

Andersson, K. and Hockey, G.R. (1975) Effects of cigarette smoking on incidental memory. Report, from the Department of Psycholo_y.

University of Stockholm, No. 455.

Beard. C.M., Kokmen, E., Offord, K.P. and Kurland. L.T. (1992) Lack of

association between Alzheimer's disease and education. Occupation. marital status, or living arrangement. Neurology, 42: 2063-2068.

Block, R.I., Farinpour, R, and Braverman, K. (1992) Acute effect. of marijuana on cognition: relationships to chronic effects and smoking

techniques. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav.. 43(3): 907-917.

Block, R.I. and Ghoneim. M.M. (1993) Effects of chronic marijuana use

on human cognition. Psychopharmacology-Berl., 110(1-2): 219-228. Bonaiuto, S., Rocca. W.A. and Lippi, A. (1990) Impact of education and

occrpation on the prevalence of Alzheimer's disease (AD) and multiinfarct dementia (MID) in Appignano, Macerata Province, Italy. Neurology. 40 (Suppl. 1): 346.

Bornstein. R.A. and Kelly. M.P. (1991) Risk factors for stroke and new psychological performance. In: R.A. Bornstein and G.G. Brown (Ed, i, Neurobehavioral Aspects of Cerebrovascular Disease, 10, Oxtwrd University Press, New York, pp. 182-201.

Botwinik. J. (1977) Intellectual abilities. In: J.E. Birren and K.W. Schaie (Ed,). Handbook of the Psychology of Aging, Van Reinhold, New York. pp. 580-602.

Bowniaan, M. and Pihl. R.D. (1973) Cannabis: psychological effects of chronic heavy use: A controlled study of intellectual functioning in chr nic users of high potency cannabis. Psychopharmacologia, 29: 151-170.

Busse. E.W. (1987) Clinical characteristics of normal aging. In: W. Men °r-Ruge (Ed.), The Elderly Patients in General Practice. Teaching and Training in Geriatric Medicine, Vol. 1, Karger, Basle. pp. 59-113.

D'Arcl. C. (1994) Education and socio-economic status as risk factors for tementia: data from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Neurobiol. Aging, 15 (Suppl 1): S40.

Dornbrush, R. and Kokkevi, A. (1977) Acute effects of cannabis on co,~:itive, perceptual, and motor performance in chronic hashish users. In: Costas Stefanis, Rhea Dombush and Max Fink (Eds), Hashish: SrLdies of Long-term Use, Raven Press, New York, pp. 69-78.

Elwar. 0.. Hashem, S., Hassan. A.A.H., El Tamawy, Abdel Naseer, M., Elv.,:n. F.. Madkour, 0.. Abdel Kader, A.A. and El Tatawy, S. (1994) Cognitive deficits in ischemic strokes: Psychometric. electrophysio' logical, and cranial tomographic assessment. J. Neural. Sci., 125: 16~;-174.

Elwan 0., Hassan, A.A.H., Abdel Naseer, M., Fahmy, M.. Elwan, F.. Abdel Kader, A.A. and Mahfouz, M. (1996) Brain aging in normal Egl. ptians: Neuropsychological, electrophysiological and cranial tomographic assessment. J. Neurol. Sci., 136: 73-80.

Folstein, M.F., Folstein, S.E. and McHugh, PR. (1975) 'Mini-mental state'. A practical method of grading the mental state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatry Res., 12: 189-198.

Franke n haeuser, M. Myrsten, A.L., Post, B, and Johannson, G. (1971) Be: avioral and physiological effects of cigarette smoking in a monotonous situation. Psychopharmacologia. 22: 1-7.

Goggin. N.L. and Meeuwsen, H.J. (1992) Age-related differences in the control of spatial aiming movements. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport, 63: 3V-372.

Greenfield, P.M. and Bruner. J.S. (1966) Culture and cognitive growth. Int J. Psychol., L 89-107.

Gronv.:all, D.M.A. (1977) Paced Auditory Serial-Addition Task: a measure of recovery from concussion. Percept. Mot. Skills, 44: 367-373.

Hayslip. B.J.R. and Panek, P.E. (1989) Biology of aging and longevity. In: B.J.R. Hayslip and P.E. Panek (Eds), Adult Development and Acing. Harper and Row, New York, pp. 40-85.

Heim,t a, NW. Bancroft. N.R. and DeKoek, A.R. (1967) Effects of smoking on sustained performance in a simulated driving test. Ann. Nest York Acad. Sci., 142: 295-306.

Heishman, S.J., Huestis, M.A., Henningfield, 1_E. and Cone, E.J. (1990) Acute and residual effects of marijuana: profiles of plasma THC lesels. physiological, subjective, and performance measures. Pharmacol. Biochem, Behav., 37(3): 561-565.

Hill, R.D. (1989) Residual effects of cigarette smoking on cognitive performance in normal aging. Psychol. Aging, 4(2): 251-254.

Horn. J.L. (1975) Psychometric studies of aging and intelligence. In: S. Gershon and A. Raskin (Eds), Genesis and Treatment of Psychologic Di-rders in the Elderly, Raven Press, New York, pp. 19-43.

Katzman, R. (1993) Education and the prevalence of dementia and aleheimer's disease. Neurology, 43: 13-20.

Kubota, K., Matsuzawa, T., Fujiwara, T., Yamguchi, T., Ito, K., W,ranahe, H. and Ono, S. (1987) Age-related brain atrophy enhanced h% smoking: a quantitative study with computed tomography. Tohoku J. Exp. Med_, 153(4): 303-311.

Macrae. K.S. (1984) Strategies underlying psychometric test responses in young and middle-aged adults of varying educational background. Paper presented at the Conference on Thinking, Cambridge. MA, August 19-23, 1984,

Melges, F.T., Tinklenberg, J.R., Hollister, L.E. and Gillespie. H.K. (1970)

Marihuana and temporal disintegration. Science. 168: 1118-1120

Meyer, J.S., Judd, B.W, Tawaklna, T., Rogers. R.L. and Mortel. K.F_ (1986) Improved cognition after control of risk factors for multiinfarct dementia. J. Am. Med. Assoc., 256: 2203-2209.

Moehle, K.A. and Lung, C.J. (1989) Models of aging and neuropsychological test performance decline with aging. J. Gerontol.. 44(6): 176-177.

Morley. J.E., Flood, J. and Silver, A.J. (1992) Effects of peripheral hormones on memory and ingestive behaviors. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 17(4): 391-399.

Mortimer. J.A. and Graves, A.B. (1993) Education and other socioeconomic determinants of dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Neurology, 43 (Suppl. 4): S39-S44.

Myrsten. A.L. and Andersson. K. (1978) Effects of cigarette smoking on human performance. In: Raymond E. Thornton (Ed). Smoking Behaviour: Physiological and Psychological Influences. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, pp. 156-167.

O'Conner, D.W., Pollitt, P.A. and Treasure, F.P. (1991) The influence of education and social class on the diagnosis of dementia in a community population. Psychol. Med., 21: 219-224.

Page, H.W. (1973) Concepts of length and distance in a study of Zulu youths. J. Soc. Psychol.. 90: 9-16.

Plassman, B.L., Welsh, K.A., Helms, M., Brandt. J.. Page. W.F. and Breitner, J.C.S. ( 1995) Intelligence and education as predictors of cognitive state in late life: A 50-year follow-up. Neurology, 45: 1446-1450.

Pope. H.G. Jr, Gruber, A.J. and Yurgelun Todd, D. (1995) The residual neuropsychological effects of cannabis: the current status of research. Drug Alcohol Depend., 38(l): 25-34.

Rafaelsen, O.J. (1972) Cannabis and alcohol: Effects on simulated car driving and psychological tests. In: W.D.M. Paton and June Crown (Eds), Cannabis and its Derivatives: Pharmacology and Applied Psychology. Oxford University Press, London, pp. 184-192.

Reitan. R.M. (1969) Manual for the Administration of Neuropsychological Test Batteries for Adults and Children. Indianapolis, IN.

Renter, R. (1992) Differences in awareness and perceptions of smokers' behaviors. Psychol. Rep., 71(1): 225-226.

Satz, P., Fletcher, J.H. and Sutker, L.S. (1976) Neurophysiologic, intellectual, and personality correlates of chronic marijuana use in native Costa Ricans. Ann. New York Acad. Sci., 282: 266-306.

Schaie. K W. (1990) The optimization of cognitive functioning in old age: predictions based on cohort-sequential and longitudinal data. In: P.B. Baltes and M.M. Baltes (Eds). Successful Aging: Perspective from the Behavioral Sciences, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, pp. 94-117.

Soueif, M.E., Yunis, F.A., Youssuf, G.S., Moneim, H.A., Taha. H.S.. Sree, O.A. and Badr, K. (1988) The use of psychoactive substances among Egyptian males working in the manufacturing industries. Drug Alcohol Depend., 21: 217-229.

Soueif, M.I., Youssuf. G.S., Taha, H.S., Moneim. H.A.. Sree. O.A., Badr, K., Salakawi, M, and Yunis, F.A. (1990) Use of psychoactive substances among male secondary school pupils in Egypt: A study on a nationwide representative sample. Drug Alcohol Depend., 26: 6379.

Soueif, M.I. (1971) The use of cannabis in Egypt: A behavioral study. Bull. Narc., 23: 17-28.

Stern, Y.. Gurland, B., Tatemichi, T.K., Tang. M.X., Wilder, D. and Mayeux. R. (1994) Influence of education and occupation on the incidence of Alzheimer's disease. J. Am. Med. Assoc., 271: 10041010.

Swarthout, D. and Synk, D. (1987) The effect of age, education, and work experience on General Aptitude Test Battery validity and test scores. Employment and Training Administration. Washington, DC.

86 0. Elwan et al. I Journal of Neurological Sciences 148 (1997) 79-86

Wagner, D.A. (1978) Memories of Morocco: The influence of age, Wilkie, F. and Eisdorfer, C. (1971) Intelligence and blood pressure in the

schooling and environment on memory. Cogn. Psychol., 10: 1-28, aged. Science, 172: 959-962.

Wechsler, D. (1981) Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised (WAIS- Zhang, M.. Katzman, R., Salmon, D. et al. (1990) The prevalence of

R). Psychological Corporation, New York. dementia and Alzheimer's disease in Shanghai, China: Impact of see,

Wesnes, K, and Warburton, D.M. (1978) The effects of cigarette smoking gender and education. Ann. Neurol., 27: 428-437.

and nicotine tablets upon human attention. In: Raymond E. Thornton

(Ed.), Smoking Behaviour: Physiological and Psychological Influ

ences, Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, pp. 131-147.

I

| Index |

| Index |

Last Updated (Monday, 20 December 2010 16:06)