| Books - Cannabis Criminals |

Drug Abuse

|

CHAPTER 1: The Problem: A Matter of Debate |

Marijuana was first identified as a "new menace" in Canada by Judge Emily Murphy in 1922. Her influential articles in Maclean’s Magazine and her book, The Black Candle, warned of the mental, physical, and moral hazards of the use of "narcotic" drugs. She listed extensive observations about opium, morphine, heroin, and cocaine, and also raised the alarm about dangers arising from marijuana and hashish. Her sources for the effects of cannabis ranged from the Chief of Police of Los Angeles to the Encyclopedia Britannica, and included this description of users by a physician in 1903:

They are good-for-nothing lazy fellows who live by begging or stealing, and pester their relations for money to Shy the hashish, often assaulting them when they refuse the demands. The moral degradation of these cases is the most salient symptom; loss of social position, shamelessness, addiction to lying and theft, and a loose, irregular life makes them a curse to their families. (1922:334)1

Judge Murphy recommended the establishment of treatment facilities along with strict legal repression of drug commerce and consumption. She could not have anticipated the complexity of the problems posed by the widespread, though criminally prohibited, use of cannabis some 50 years later. Even though some of the harsh provisions incorporated into Canadian narcotic drug law in the 1920s have been removed (e.g. whipping, no appeal from conviction, deportation of convicted aliens), others are still reflected in the current laws governing illicit drugs (e.g. special search warrants, lengthy terms of imprisonment, mandatory minimum prison sentences). Treatment has been a much less prominent feature of Canadian drug policy over this century than a strict law enforcement response.

Cannabis use did not present as a problem in 1923 when it was first added to the schedule of prohibited "narcotics." Similarly it was still not assessed as a significant problem by a Special Senate Committee in 1955.2 But the situation changed dramatically in the 1960s. In Canada and other western countries, cannabis use moved from the fringe of popular culture to the mainstream. Youthful members from all strata of society experimented with the drug in increasing numbers. In so doing, they exposed themselves to the possibility of criminal sanction. The wheels set in motion by the legislative initiative of the 1920s began to affect the lives of many young people as they were subjected to arrest, criminal records, and imprisonment. More than one observer has found irony in the widespread application of severe narcotics laws in North America. Originally the laws were directed at a racial and social minority ( Asians in Canada, Mexicans in the U.S.), then beginning in the 1960s, they were applied to indigenous, often white, middle class youth (C look, 1969; Green, 1979; NIDA, 1979). The problem of what to do about cannabis became more pressing as both demand for the drug and the enforcement response escalated. ;

Efforts to document the extent of cannabis use throughout the 1970s have shown a consistent pattern of increase, particularly among younger persons. In Canada, a nationwide survey of adults (18 years and over) found in 1978 that 17.2% had used marijuana or hashish at some time compared to only 3.4% of a similar group in 1970 (Rootman, 1979). From this study, current consumption levels were highest among the 18 to 29 age group, with 10% reporting use on several occasions in the past month. Surveys of high school students also have shown rises in direct cannabis experience to the point where by 1979, nearly half of graduates had tried the drug (Smart and Fejer, 1974; Smart et al., 1979). Similar trends were documented in the United States during the 1970s, including an increase in daily or near daily use by high school seniors from ¢% to 11% between 1975 and 1978 (Johnston, 1980). By 1980, there seemed little doubt that the use of cannabis was not to be a fad. ‘

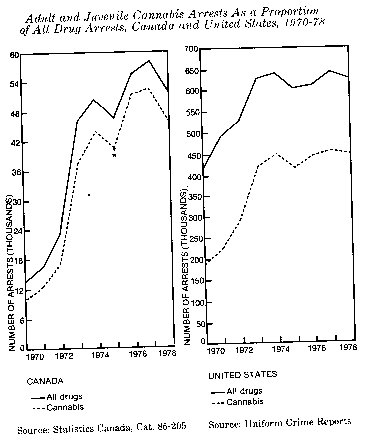

The mobilization of the criminal justice system in response to this growing trend resulted in mounting numbers of new criminals whose crime was the possession of cannabis. By 1979, more than 200,000 Canadians, about 85% under 25 years of age, had been found guilty of this offense.3 The magnitude of this legal response can be gauged by the fact that by 1976, a cannabis offense accounted for one out of every eight federal criminal charges, excluding highway traffic offenses (Bryan, 1979). By 1978, the total number of convictions leading to custodial sentences for cannabis possessors was nearly 10,000.4 An overview of federal cannabis policy concluded that "Canada annually arrests more of its citizens per capita for cannabis possession than any other country in the world."5 This enforcement effort, if not equalled, was paralleled in the U.S., where in excess of 400,000 marijuana arrests per year were recorded from 1973 to 1978.fi In the later year, marijuana arrests represented 72% of all American drug arrests, while in Canada in 1978 cannabis offenses accounted for 89% of all illicit drug charges (see Figure 1).

The extent of cannabis use and the application of criminal sanctions against users have posed a dilemma for legislators since the late 1960s. The potential health and safety risks presented by excessive or irresponsible use have been complicated by the social costs and adverse individual consequences inherent in the prohibitionist control policy. Much of the initial controversy was concerned with whether cannabis was, indeed, "like heroin" in any other aspect than its legal definition as a "narcotic." However, policymakers soon had at their disposal evidence which permitted an advance of the debate beyond the era of sensationalism, propaganda, and error. ] Lt was established that cannabis was not a "narcotic" in any pharmacological or behavioral sense, its addictive properties were mil limal, and its use did not cause people to become criminals or mora] degenerates. (Le Dain, 1972; Shafer, 1972). Questions regarding the more subtle, long-term health effects on humans were controversial and stimulated further investigation.7 The stage was set by the mid-70s for a more balanced perspective on the issues surrounding an appropriate cannabis policy.

|

The decade of the 70s had opened with the deliberations of National Commissions in both Canada and the U.S. which were formed to investigate the illicit drug use phenomenon and make recommendations. Both bodies, while accepting the objective of discouraging cannabis use, adopted a principle of cost-effectiveness as their guide. The Le Dain Commission in Canada phrased the issue in these terms:

The object of our social policy must be to reduce the availability and demand of cannabis as much as possible, if that can be done at an acceptable cost. The question is whether, and to what extent, the criminal law is a proper instrument for such a policy. The answer to this depends on how effective the criminal law is in achieving its purpose, what the costs are of using it, and whether there are alternative methods of control that would achieve the purpose as effectively at less cost. (1972:275)

Similar reasoning was voiced by the Shafer Commission in the U.S. (1972:27,135). Given this strategy of attempting to resolve the cannabis quandary within a cost-benefit framework, what were the effects of the prevailing legal policy which were identified as significant?

A major adverse consequence was considered to be the effects of criminal conviction, particularly of young people. The Le Dain Commission identified this as "probably the most serious of the special costs in the application of the criminal law" (1972:293). This body recognized the inherent harshness of contact with the criminal justice system through arrest to court processing, and also enumer-ated the potential liabilities that could follow from the blot of a criminal record. The Shafer Commission echoed these concerns, as did the U.S. Strategy Council on Drug Abuse at a later date when it called the price imposed for the presumed deterrent benefit of the law as "high in terms of stigmatizing casual users with criminal records" (1976:54).

What was lacking in both the American and Canadian National Commission reports on cannabis, and in much of the debate since, has been direct evidence of adverse individual consequences of criminalization. While many projects have been conducted on the physical, psychological, and social effects of using cannabis, the acquisition of specific knowledge about the impact of the "criminal conviction on young lives" (Le Dain, 1972:292) was not undertaken by either the Le Dain or Shafer Commissions. This cost area was expressed conventionally in terms of number of convictions without supporting evidence of actual negative repercussions. Furthermore the acceptance of deterrent effectiveness was also not subjected to empirical scrutiny, because, as Le Dain noted "we cannot put in question the assumption which underlies the whole of our criminal law" (1972:289). While it is reasonable to assume that the costs of criminal sanction exist, and may be elusive and difficult to quantify with precision, the assumption that has continually been made in the cannabis debate is that they are "high."

This evaluation calls for corroboration. The study reported here has attempted to redress this imbalance by examining a group of criminalized cannabis users. A representative sample of "first offenders" was interviewed at the time of sentencing and one year later. Their experiences of becoming criminals and the related social effects provide a previously unavailable component of the cost-benefit analysis pertaining to cannabis policy. This work points to the value of obtaining an empirical base for the assessment of existing drug laws and proposed reforms. While recognizing that research cannot answer the basic .value question of individuals’ right to take drugs that may harm only themselves, systematically collected data may aid the policy maker in this process of reconciliation of old law and new pressures. Glaser’s directive describes this role for the researcher in a policy relevant area:

What sociological criminologists have been doing but need to do much more adequately is to estimate all the social costs and benefits that would result if criminal law or alternative means were used in an effort to reduce [drug use]. (1971:35)

The social effects of punishment on individuals, encompassing both costs in a variety of spheres of their lives and the possible benefit of deterrence from further cannabis use, form the substance of the findings in this study. They are reported in Chapters 5 and 6. The theoretical rationale, the historical-legal background of the current cannabis prohibition, and a model of criminalization are presented in Chapter 2. Criminalization throughout this study is defined to include the process of arrest through to official labeling with a criminal record, and the subsequent effects, as they vary with the sentence received. Chapter 3 describes the design of the study and the characteristics of the study population. Chapter 4 highlights the process of "becoming a cannabis criminal" through the subjective perspective of the offender. As noted, the next two chapters deal with the impact of criminalization as measured at the time of sentencing and one year later. The final chapter concerns the implications of the results of the study for the user, the law, and society. It is concluded that being criminalized for cannabis possession has some adverse u consequences to individuals’ lives and almost no specific deterrent effect.

Notes CHAPTER 1: The Problem

1 The referencing system in this text cites the source by author’s name, followed by year of publication, and then page number(s) if quoting directly. For example, Smith (1970:223).

2. The Senate of Canada: Proceedings of the Special Committee on the Traffic in Narcotic Drugs in Canada, 1955, p. xii.

3. Source: Bureau of Dangerous Drugs, Health Protection Branch Health and Welfare Canada.

4. This figure does not include the approximately 10,000-15,000 persons who, by 1978, were incarcerated in default of payment of a fine (estimated by Bryan, 1979).

5.Cannabis Control Policy: A Discussion Paper. Health Protection Branch, Health and Welfare Canada (Blackwell et al., 1979).

6. Source: Uniform Crime Reports. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice.

7. The burgeoning interest in the effects of cannabis use is reflected in the approximately 1,500 pieces of research, the large majority of which postdate 1972, collected in a forthcoming annotated bibliography (Kalant et al.). The scientific evidence has increasingly supported the conclusion that the chronic heavy use of cannabis, and use by individuals at particular risk because of pre-existing conditions, pose potential health hazards to humans (see Tinklenberg, 1975; Fehr et al., 1980; NIDA, 1980).

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|