| Articles - Anabolics, steroids & doping |

Drug Abuse

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF DRUG POLICY, VOL 5, NO 1, 1994

SPORT FOR ALL BUT IS IT SUITABLE FOR CHILDREN?

For many years now, those working in drug education have advocated the benefits of adolescent involvement in sports as a protection against the use of drugs. Of increasing concern, however, are recent reports of the use of performance-enhancing drug use in sport, particularly anabolic steroids. Paul Melia describes its use by young Canadians, and attempts to understand the root causes and to consider the programme and policy implications.

BACKGROUND

The strategic use of sport has been widely recommended in programmes trying to prevent adolescent use of a variety of drugs ranging from nicotine to heroin. Ironically, we have at the same time been aware of the growing use of recreational drugs, especially alcohol, as part of the sporting experience. Such use has tended to be mainly celebratory in nature. However, recent reports tell of the use of performance,enhanc, ing drugs in sport, particularly anabolic steroids, by young Canadians

Unfortunately, the use of anabolic steroids and other performance-enhancing substances is not limited to the world of high-performance athletes. A recent review of the literature by the Canadian Cen, tre for Drug,free Sport (CCDS) suggests that steroid use, in particular, is not uncommon among younger, developing athletes. The literature suggests that, among athletes at the high school and college level, use of anabolic steroids runs at about 5% overall, with usage among non-athletes being somewhat lower, and reported usage among females being significantly lower than that of males. The problem is compounded by the growing evidence that anabolic steroids are also being used for reasons other than sport; the main motivation (for this non,sport specific use) being that of body- image enhancement.

In Canada, before the establishment of the CCDS, we faced a situation where the size and magnitude of the doping problem was largely unknown. Although there were some who said we didn't have a problem of performanceenhancing drug use in sport, others said it was a much bigger problem than we imagined. Some claimed that performance enhancing drug use was an isolated occurrence, one that had always been there but that was small, stable and of little concern. They argued that focusing attention on isolated cases of use created a problem where one didn't exist. Still other people in Canada were claiming that the problem of doping was growing rapidly and that it extended well beyond Olympic athletes.

Why there was or wasn't a problem of drug use in sport had an equally wide-ranging set of explanations. For example, many of those involved in sport have said the problem only exists because athletes are not well informed about the health consequences of doping whereas others suggest it is because athletes do not believe that doping is cheating, i.e. they see it as a question of ethics. Some claim we simply need to improve testing and strengthen the penalties as a means of solving the problem of doping in sport. The various assumptions and perceptions that exist in and outside the sport community are, indeed, numerous.

CANADAS NATIONAL SCHOOL SURVEY ON DRUGS AND SPORT

What we had in Canada was a situation where many different groups were saying different things about the doping issue, resulting in a very puzzling picture of the problem and its solution. Interestingly, what was being said was not necessarily based on empirical research. To help us better understand the nature and extent of the doping problem in Canada, the CCDS decided to carry out empirical research; to go out and to talk to as many young Canadians as possible. In fact, in the largest single survey of its kind on this subject in Canada, we asked questions on drugs andsport of over 16 000 11to 18-year-old school children.

The purpose of the survey was not simply tofind outwho was using what substances, but rather to go beyond the available preva, lence data and begin to explore the thoughts and opinions of users and non-users. Specifically, we asked young Canadians about their knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and use of a variety of performance-enhancing methods and substances, including anabolic steroids. What we found was both comforting and alarming.

ANABOLIC STEROID USE

In the case of anabolic steroids we found a prevalence of 2.8%. Now while this might appear low and give reason for comfort, what it means in a country the size of Canada, with a population of about 3 million 11-18 year olds, is that some 83 000 of our young people have probably used anabolic steroids, at least once in the last year.

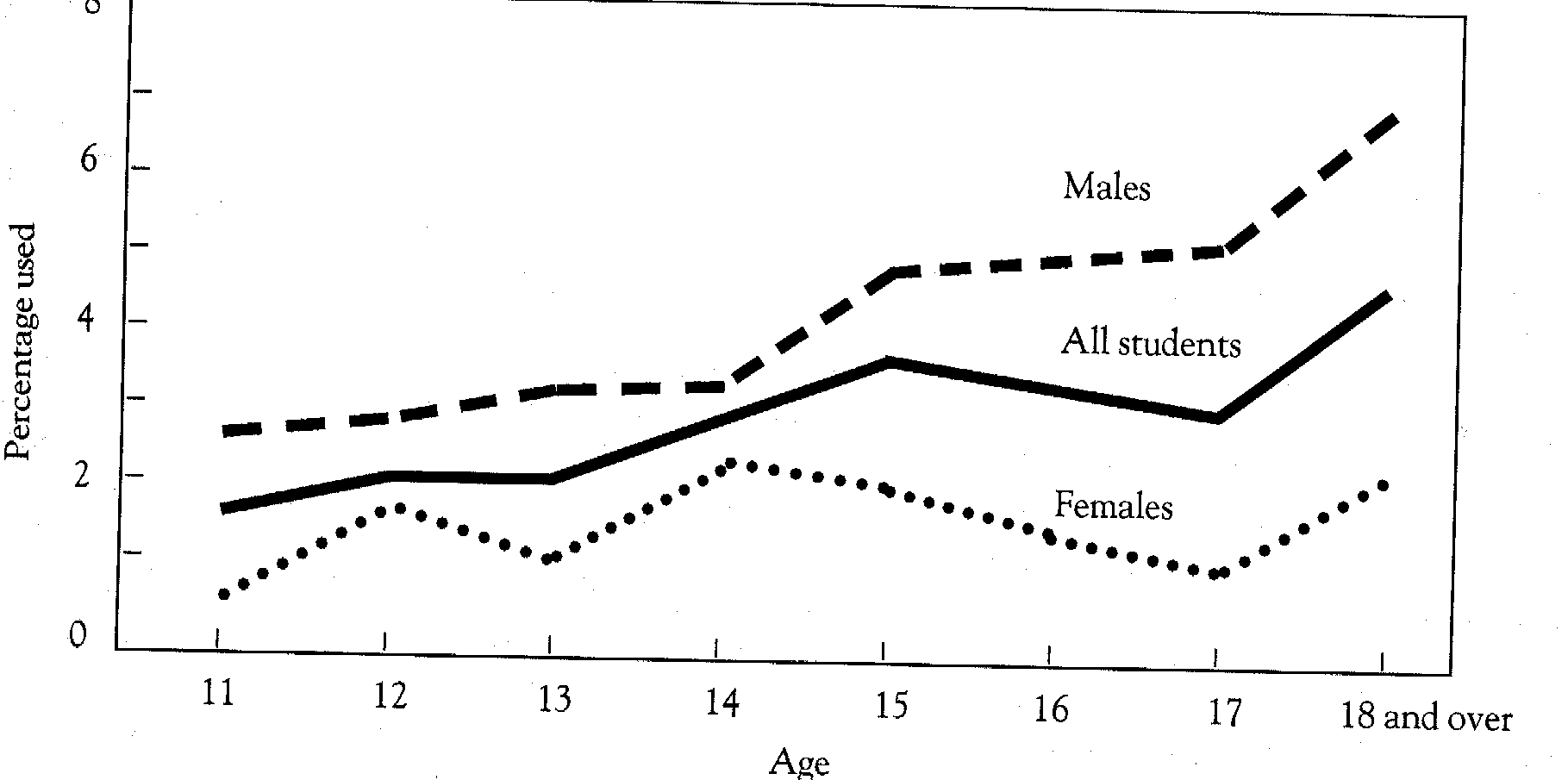

FIGURE 1: Percentage of students who had used anabolic steroids by gender.

Our survey probed a little deeper on the subject of anabolic steroid use. We looked at the relationship between age and gender and, as Figure I illustrates, we found a sharp increase in use for mates at age 14, an increase of the magnitude one might associate with age of onset. Females, on the other hand, appear to have a fairly flat relationship with age, with no clear age of onset suggested. What this highlights is the apparent need for our prevention programmes to target youth as young as 11-13 years of age.

We also asked steroid users about the use of needles. As Figure 2 illustrates, 29.4% of our steroid users indicated that they used needles to inject anabolic steroids. Alarmingly, of that group of needle users, almost one-third said that they shared needles. The public health implications of these findings are obviousty quite profound. Although a harm-reduction strategy of providing clean needles to steroid users would appear to present itself here, it must be remembered that the sport community has to date adopted a zero tolerance policy when it comes to the use of banned substances such as anabolic steroids.

DOPING AS A SOCIAL ISSUE

FIGURE 2: (a) Use of steroids; (b) use of needles by steroid users; (c) needle sharing by steroid users.

As previously mentioned, our research goes beyond documenting prevalence. We view the doping issue as more than simply a sport or health issue. We view the doping issue in ecological terms and see it as a social issue where drug use does not occur simply because some athletes or individuals do not understand the health consequences or because they are not aware that such behaviour is against the rules. In our view, doping occurs because the sport environment and the larger social environment create conditions and send messages that in many ways make it easy for and, indeed, encourage athletes to dope. This happens because the extrinsic rewards of sport, for example, gold medats, public recognition, corporate monies, media attention, and so on, become so strong, and so much importance and value are placed on them that the athlete loses sight of the intrinsic goods of sport. What gets lost in the process are the reasons why young athletes were drawn to sport in the first place. The fun, camaraderie and excitement of playing the game, the pleasure and joy they experienced in pursuing sporting excellence, and the personal satisfaction that comes from knowing they have pushed themselves to per-form to the maximum of their abilities. These extrinsic rewards, then, may override the internal goods of sport and provide real and tangible benefits which compel athletes to use drugs. With this view in mind, our survey also looked at what the students thought and believed about sport along with their motivations for use.

In looking at motivations for using anabolic steroids we found an interesting dichotomy. Fifty-four per cent of those students using anabolic steroids indicated that they were using them to improve their female, or whether they were extremely involved in performance in sport. At the same time, 46% of users indicated that their reason foruse was to improve their appearance. We then looked only at those students who used anabolic steroids to enhance their perfor, mance, and found that 59.7% were males and 38.9%were females.

FIGURE 3: Percentage of students who reported having used anabolic steroids by sports team involvement. *No statistically significant difference. Not involved; E] involved.

We also wanted to know where we would most probably find these students in terms of their sport involvement. Figure 3 shows very clearly that increased involvement in sport leads to an increased likelihood of using anabolic steroids or, stated another way, as the level of competition increases so too does the reported use of steroids. In fact, for those students involved in sport at the provincial level (one level below our national level athletes) as many as 7% are using steroids.

However, if 7% of our provincial level athletes admitted to using steroids it remains that the vast major, ity reported no such use * Although this was comfort, ing to discover, the absolute numbers of reported users that this represents cannot be ignored. And whether our students were male or competitive sport, tells us only a small part about the context of anabolic steroid use. What about the actu, al social conditions that give rise to this behaviour? When we looked at social indicators, when we began to explore what these students thought and felt about sport, then we started to understand much more clear, ly and precisely who the steroid users were likely to be, why they might use anabolic steroids and what could be done to prevent their use. For example, students' attitudes towards winning and cheating, the value they place on doing their best and the behaviour of their friends tell us much more about who is using steroids than any of the other variables we had looked at to this point.

Indeed, based on results from our National School Survey, we believe that attitudinal data can be an extremely strong predictor of use. Our research to date indicates that, based solely on their attitudes and beliefs, a significant number of young Canadians may be at risk of using anabolic steroids. It is apparent from such research that there are many young Canadians who think like a typical steroid user, believing such things as: 'It'S OK to try anabolic steroids once'; 'In sports, winning is the most important thing'; 'Using drugs to do better in sports is not cheating'; and 'Olympic athletes who use drugs should be allowed to compete'. Furthermore, we can expect a notable shift towardssuch attitudes as young Canadians grow older, with a corresponding increase in the use of steroids.

Based on our data, we believe attitudes and beliefs alone can serve as powerful predictors of steroid use. Shift the beliefs toward what we would call a positive view of sport, and you can virtually predict drug-free sport. Allow such attitudes to shift towards the negative end and there will be no such thing as drug-free sport. This is underlined by the finding that, among those students with the greatest number of negative beliefs, 69% were steroid users, whereas among those who held none of these negative beliefs, steroid use was virtually absent.

SOLUTIONS?

What this tells us is that if we want to prevent the doping problem - if what we want are long-term solutions founded on lasting social change - then we have to address the social conditions that give rise to these attitudes and beliefs. We know that we cannot significantly reduce prevalence if we simply tell our athletes 'j ust say no'or'don't do drugs'. The solution is not that simple. There is no question that regular testing of athletes remains an important part of the solution to the use of banned substances and methods. Canada has one of the most comprehensive Arug testing programmes in the world, conducting almost 2500 tests a year in over 50 sports, with 60% of those tests being of little or no notice to the athlete. And yet, given that such testing helps, and even given highly publicised cases of athletes caught doping, testing alone won't change attitudes. And what the CCDS learned from the survey is that changing young Canadian's attitudes about this issue is critical to achieving drug-free sport. For this reason, the CCDS has developed a national education campaign, 'Spirit of Sport'. This campaign does not focus on the negative consequences of doping. Instead, it emphasises the values and internal rewards in sport that are contrary to drug use: the pursuit of sporting excellence and human excellence. 'Spirit of Sport' is designed to celebrate one's personal achievements through balanced and honest competition, self-discipline, and respect for one's body and the rules. More than this, however, the 'Spirit of Sport'is about a re-emphasis on the internal rewards of sport. Rewards that can only be achieved through a knowledge and belief that success was achieved through personal effort without resorting to external assistance such as doping. This approach is not against striving for excellence or striving for victory. Rather, it promotes attitudes which recognise that drug-supported victory is no victory at all.

In essence, we are suggesting that if doping is to be prevented sport needs a &values' overhaul. And more than simply clarification of values, we need a collective agreement within society on what it is we wish to value in sport. We then need to take account of the social and environmental circumstances that give rise to a set of attitudes and beliefs that we have described to be the breeding ground for drug use in sport. If the sport system is repeatedly and consistently telling athletes that, for example, winning is the only thing that matters, that it is the only thing that is valued in sport, then corresponding values and attitudes will, not surprisingly, emerge. Indeed, over conformity to such values will lead inexorably to drugfilled sport.

What this means is that all those involved in the sport system have a role to play. Coaches are of critical importance given the pervasive influence they have over their athletes' values, moral reasoning and decision-making. Parents need to review their own sporting values and to examine their motives for enrolling their children in sport. Those working in the field of sport medicine including physicians, physiotherapists, trainers, etc. must seek to balance the desire to enhance the athletes' ability to compete with their responsibility to protect the health and well-being of the athlete. The mass media tends to portray sporting experiences as all or nothing adventures separating competitors into winners and losers - surely the game itself and what happens before, during and after is every bit as newsworthy as the final score. Or, at the very least, we must agree that this is so if we wish our children to believe it. Sport contributes to society in many ways. Through their involvement in sports young people can learn valuable life lessons ranging from discipline and commitment to camaraderie and teamwork. Participation in sport can also contribute to the development and enhancement of individual self-esteem. The values that give rise to drug use in sport and drug use itself pose a serious threat to the positive contribution sport can make to the pursuit of not just sporting excellence but also to the pursuit of human excellence. It is this situation that raises the question'Is sport a healthy place for children?'.

This question is not idly asked. The CCDS conducted public opinion polling in Canada over the last two years examining the extent to which the drugs and sport issue has influenced parents' decisions to enrol their children in organised sports. What we found startled us. Eighty,one per cent of respondents said that the use of banned substances and methods by professional and amateur athletes was a'somewhat'to (very serious' problem. Furthermore, the use of anabolic steroids to enhance body-image was considered a'somewhat' to 'very serious'problem by 79% of respondents. Finally, 48% of respondents said that the issue of drugs and sport would'somewhat'to 'strongly' affect their decision to enrol their child in organised sport. What this shows is that even rare cases of doping can cause public distrust and scepticism. When the ethics of sport are questioned, it can lead to a decrease in public support for Canadian sport and in future sport participation. Canadians clearly are questioning whether or not sport is a healthy place for their children.

CONCLUSIONS

The use ofperformance-enhancing substances by athletes of all ages, and in particular the use of anabolic steroids, is a significant and serious problem in Canada. The motivations for use appear evenly divided between sport performance and the enhancement of body-image. Although there are many factors that may account for this phenomenon it appears that there are a predominant set of attitudes and beliefs that correlate very highly with this behaviour. Clear, ly, traditional information-based strategies that focus on health consequences and playing by the rules will have important but only limited impact on this problem. Strategies aimed at reducing the incidence of such behaviour must strike at the root causes of the problem. Our research clearly suggests that these root causes are linked to how our developing athletes experience sport and the attitudes and values they develop along with their sport skills. If we can create a sport system that supports and promotes a core set of values then we will have gone a long way toward achieving drug-free sport.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to note the significant contribution to this work by Price-Waterhouse (Ottawa) for their work in designing the research methodology and conducting the preliminary analysis of results for the National School Survey. In addition Victor Lachance, CEO and Leslie Greenberg, Coordinator, Special Projects, both of the Canadian Centre for Drug-free Sport, contributed important ideas to the development of this paper,

For further information please contact: Paul Melia, MHA The Canadian Centre for Drug-free Sport, 702-1600 James Naismith Drive, Gloucester, Ontario KlB 5N4, Canada.Telephone: (613) 7485755. Fax: (613) 748-5746.