| Articles - Anabolics, steroids & doping |

Drug Abuse

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF DRUG POLICY, VOL 5, NO 1, 1994

ANABOLIC STEROID USE: PREVENTION AND EDUCATION

Frank Ardito, Paul Goldstein, Michael Bahrke and Thomas Satder conduct a pilot study of the perceptions of users and non-users regarding anabolic-androgenic steroid prevention and education.

INTRODUCTION

The use of anabolic-androgenic steroids (AASs) has become an important social issue throughout the world. It has been reported that as many as one million Americans have used AASs, three-quarters of which are high school students (Giannini, Miller and Kocjan, 199 1 ). ManyAAS users are athletes of all ages and levels who wish to enhance their performance. Still there are others: the adolescent hoping to gain peer acceptance, the police officer who justifies the need to 'juice'by citing the risk and physical demands of his or her job, the female weight lifter who refuses to accept the physiological differences between men and women.

Since the inception of AAS use for non-medical purposes in the USA, efforts have been made to deter individuals from their use of AASs. Professional communities (e.g. doctors, researchers, educators) began a campaign against illicit AAS use by denying that ergogenic effects actually occurred. The AAS-using community responded by continuing to use these substances and further electing to disregard any'propaganda' literature on the adverse effects of AAS use.

In 1984, the American College of Sports Medicine modified its position statement on AASs to state that, in fact, AAS use may produce ergogenic effects. Nevertheless, there is still a definite lack of trust on the part of AAS users about medical information on the adverse effects of AASs.

Along with the widespread use of AASs, there has been an accompanying problem of misuse and abuse. In 1991, anabolic steroids were made controlled substances in the USA. Rules, regulations and laws at local and federal levels strictly limit AAS use to those few who need the drugs for a narrow range of approved medical purposes. There is now a lack of availability of legitimately produced pharmaceutical products, accompanied by a shortage of medical advice and information for the illicit AAS user. Consequently, many users are taking dosages in excess of what they might need for a successful work-out regimen. Further, users may be unaware of specific health consequences of steroid use, AIDS risks from needle sharing, risks from mixing steroids with other drugs, and so on. Finally, asa result of the illicit sources of AASs the user cannot be sure if the drugs are pure, if the potency indi, cared on the label corresponds to the actual potency of the product, or even if the product is actually an anabolic steroid. A need for AAS education and abuse prevention programmes is evident. There is little empirical evidence to provide direction for the design and maintenance of needed education and abuse prevention. Additionally, tim ited funding exists for programmes in this area.

PURPOSE

The purpose of this study was to analyse a subset of data concerning AAS prevention and education obtained from the currently ongoing research project,'Anabolic steroids: A new issue in prevention research'(Goldstein, 1992). First, a comprehensive review of the literature was undertaken with the prinlary purpose of collecting literature pertinent to education and prevention programmes focusing on AAS use. Second, the survey was administered through a series of interviews whichwerepartof the larger study to collect perceptions and recommendations of mate adult AAS users and non-users. It was hoped that analysis of results would generate hypotheses whereby future quantitative research efforts might be carried out, and valid recommendations might be made regarding the design and implementation of comprehensive AAS awareness programmes.

HYPOTHESIS

The hypothesis for this research was two-fold. First, it was hypothesised that respondents (both AAS users and non-users) would perceive current and former AAS prevention/educat ion programmes as inaccessible, due largely to a lack of knowledge concerning their availability. Second, it was hypothesised that respondents would view such programmes as generally ineffective, due primarily to inaccurate, Outdated and/or biased information being presented by programme administrators.

RESEARCH METHODS

The larger study from which the data presented herein were gathered began in 1992. Over a 3-year period, this research is collecting data from a cross-sectional sample of 400 men and women in the Chicago area. Basic research questions include the following:

frequencies, volumes, modes of ingestion and types of AAS used;

extent and circumstances of needle sharing;

concomitant use of other substances with AAS and interactive effects;

positive and negative physical and mental health consequences of AAS use;

vulnerabilities for AAS use;

sources of illicit AAS, patterns of illicit distribution, means utilized by users to support AAS use;

relationships between AAS use and distribution to aggression and violence;

ethnographic description of body-budding and steroid-using subcultures in urban and suburban gyms and health clubs;

motivations for cessation of use by former users.

The final sample will include 300 AAS users (at least 50% of whom will be current users) and 100 nonusers (recruitedfrom thesame gymsas theusers). Both the users and the non-user groups will contain a 2:1 ratio of males:females. All research subjects are over the age of 18 years.

An important point of significance in this study lies in the uniqueness of its subject pool. First, the subjects are adults, unlike the majority of previous research studies which have focused largely on adolescents. Second, the participants do not belong to a particular group, whereas former projects have targeted Oite athletes in general, or those involved in specific sports (such as football or body-building). All research subjects receive a Life History Interview (administered over an average of about four onehour sessions). AAS using subjects receive an additional Steroid Focused Interview (also administered over an average of about four one-hour sessions). Questions concerning experiences with, and perceptions of, AAS education and prevention programmes were asked as part of the Life History Interview. Field staff, responsible for recruitment of subjects and administration of interview protocols, were all familiar with the research milieu under study. They include three males and one female. Two are bodybuilders (one, a former gym owner, had substantial success in competitions), one is a powerlifter and one is a former college varsity basketball player.

Selection criteria for the pilot study presented herein consisted of the following: all subjects were males; a history of AAS use (any personal use of AAS, currently or in the past, for non-medical purposes) was required for half of the subject pool. Additionally, subjects were required to have experience in one of two areas. The first area was organised sports participation (such as football and swimming); the second area was weight lifting (such as body-building and powerlifting, as well as any form of unorganised non-competitive weight lifting). There were no specific criteria regarding the level of participation (e.g. local, national) foreitherof the two areas. Moreover, the amount of exposure to either of these areas must have been demonstrated as consistent participation over a minimum of at least one year.

A total of twenty subjects were included for this study. Each participant met the selection criteria mentioned above. The relatively small subi . ect pool served, not to determine any specific cause and effect relationships, but rather to collect data useful for the generation of additional hypotheses, to be addressed with data from the larger study.

Selection of subjects occurred in the general vicinity of Chicago, Illinois. Participant recruitmenC took place through three primary sources. The first source was personal contacts. The primary author has consid erable experience with various strength and physique oriented populations. Some of these include weightlifting organisations and associations, health clubs, fitness centres, powerlifting teams and body-builders. Furthermore, this researcher has extensive personal contact with adult male AAS users and non-users.

The second source was training centres. These included health clubs and weight-training gyms. The primary author trained at several of these locations throughout the Chicago area. Doing so provided an opportunity to develop a rapport with other weight lifters. This ethnographic-oriented approach to subject recruitment for AAS research has been successfully demonstrated and documented byGoldstein (1990).

The third source for recruiting subjects was strength and physique contests. This included both body,building and powerlifting competitions. Participants and spectators were sought out at these events, and qualified individuals were asked to participate in the study. All of these individuals gave verbal consent to participate in this study.

The general topics covered in this subset analysis included:

- Personal demographic characteristics (including age, race, education level and social class level).

- Qualifying data (including history of AAS use).

- Core data

- accessibility to AASs;

- knowledge of AAS rules, regulations and effects;

- concern with body-image;

- perception of benefits from AASs,

- prior experience with AAS prevention/educa tion programmes;

- recommendations for AAS prevention/educa, tion programmes;

- perception of adequacy of AAS research efforts.

Before the administration of this survey, private locations to conduct the interviews were determined. One site was the AAS field officel located in the School of Public Health at the University of Illinois at Chicago. When necessary, the survey was administered at a site more accessible to the subject, such as a health club or weight-training gym. In this instance, permission to conduct the interview was requested from the owner/management of the particular location.

Once the location had been established, the nature and purpose of the research were explained to the subject. This was included in the informed consent. The subject was then given the opportunity to read the informed consent or have it read to him by the interviewer. Subjects were also informed that a Federal Certificate of Confidentiality had been granted for this study (this certificate protects the confidentiality of information provided by the subject from use in criminal, civil, administrative or other legal proceedings). Once the subject acknowledged an understanding of the materials explained to him, and agreed to participate, he signed the informed consent. After these steps were taken, the survey was administered.

DESCRIPTION OF SAMPLE

Responses from the first ten users and the first ten non-users in the larger study were used for this report. Subjects answered four questions regarding their age, race, education level and social class while growing up. Chi-squared analysis revealed no significant difference between status of use and any of these variables, Eighteen (90%) of the subjects were below the age of 30, with 11 (55%) between the ages of 24 and 29. Fourteen (70%) of the respondents described themselves as White, three (15%) as Black, two (10%) as Hispanic, and one (5%) as Asian. Seventyfive per cent of the respondents had completed'some' college education. The majority, 55%, of the total sample had obtained a college degree. Ten (50%) of the respondents reported being'middle class'. The remaining ten (50%) subjects were evenly distributed, five (25%) having grown up as lower middle or lower class and the remaining five (25%) beingraised in upper middle or upper class families. Both users n=10) andnon-users (n=10) ofAASwereaskedwhy they used or did not use anabolic steroids. Four of the ten users stated that their reason for using was to enhance athletic performance. Five of the ten users used AAS to increase strength and/or size. Of the nonusers, four of the ten did not use because of the side effects associated with AAS use. Two of the ten nonusers simply stated, 'I don't do drugs'.

ANALYSIS OF DATA

As a result of the small sample size (n=20) and the qualitative nature of this study, descriptive statistics serve as the primary means of analysis. Responses to each survey question have been described using histograms, comparing each response category to status of use (non,users versus users). Highlights of each graph are explained. To test whether any statistical significance exists, Yates'corrected chi-squared analysis was used. This categorical data analysis of contingency tables uses the Yates' correction to account for some of the data cells which contained less than five observations. Additionally, the standard alpha level of 0.05 was modified to 0. 10 to account for the small sample size.

The first core independent variable is availability of AAS. Fourteen (70%) of the subjects claimed AASs are at least'somewhat available'. Of these, nine respondents (45%) were users whereas five (25%) were non-users. No statistically significant difference xistedbetween status of use and availability of AASs.

Next, subjects were asked whether nutritional supplements could be as effective as AAS. Seventeen (85%) of the respondents said no, nine of whom were users and eight non-users. Responses between users and non,users were essentially similar, and chisquared analysis supported this finding.

Concerning body-image, only one subject reported that he was not more concerned with his weight and body shape than most males of the same age. The remaining 19 (95%) respondents reportedbeing more concerned with their weight and body shape than other males. Ten of these subjects were users and nine were non-users. No statistically significant differences existed between status of use and concern over body-image.

Knowledge of laws governing AAS use was also surveyed. Seventeen (85 %) subjects reported having knowledge of the existence of laws restricting posses, sion and/or sales of AASs. Nine of these respondents were users andeight were non,users. These essentially similar responses between users and non-users reveal no significant difference between AAS use and awareness of laws governing AASs,

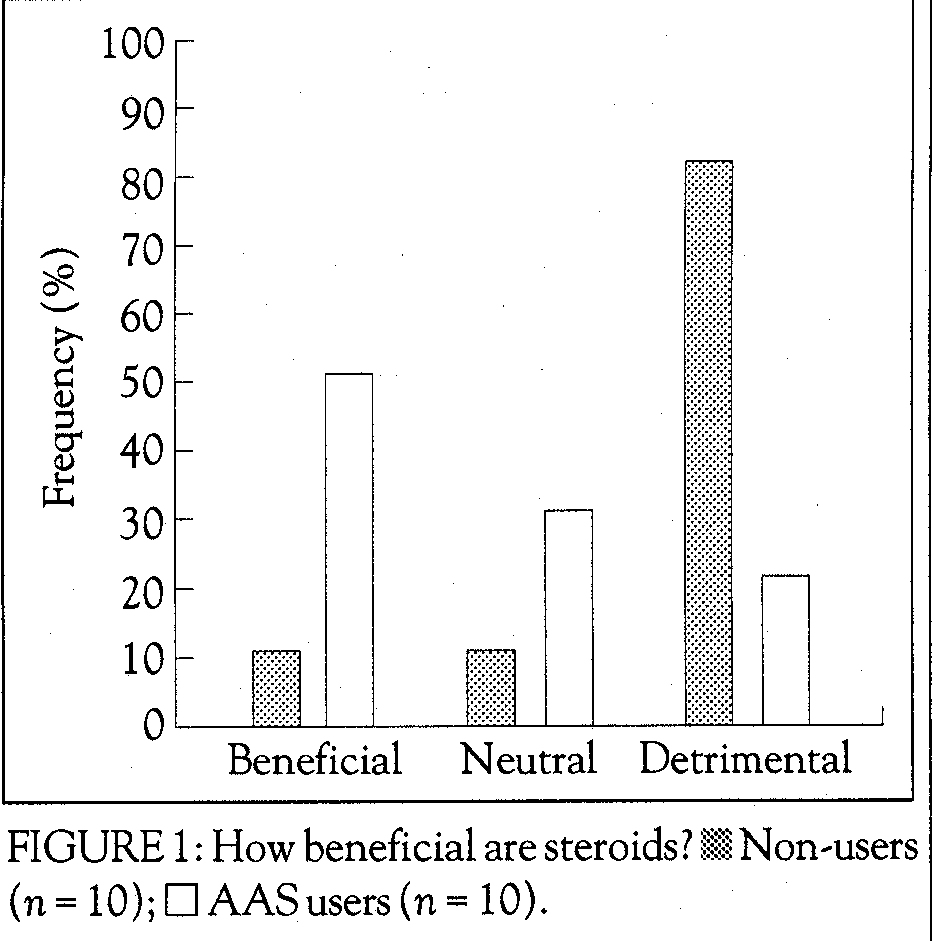

A statistically significant difference was found between status of use and respondent's overall perception of benefits from using AAS (Figure 1). Eight (80%) of the non-users reported that AASs are detrimental, compared to only two (20%) of the users. Additionally, only one (10%) non-user perceived AAS use as beneficial, whereas five (50%) users perceived AASs as such.

Respondents were also asked the question, 'Does drug testing in sport have any affect on steroid use?'. Seven (70%) of the non-users reported that drug testing discourages AAS use. In contrast, only three (30%) of the users believed that drug testing in sport discourages AAS use.

Subjects were asked whether they had ever attended any form of AAS education/prevention programme. Seventeen (85%) of the respondents had not attended any type of programme. Fourteen (70%) of these subjects stated the reason for not attending such programmes was unavailability and/or ina~cessibility. Of those respondents who had attendetl programmes, two of the three reported doing so for the purpose of increasing their knowledge regarding AASs.

Figure 2 describes the subjects' perceptions of the effectiveness of past education/prevention programmes. All subjects were asked to record their perceptions, regardless of whether they had ever attended an education/prevention programme. Twelve (60%) of the respondents demonstrated definite opinions, even though they had not attended such programmes. The opinions of those subjects were formed by hearsay and anecdotal information pertaining to programmes that were communicated within the gym culture. They are presented here as depictions of attitudes towards education/prevention programmes that are commonly held by our sample of gym 'regulars'. This histogram clearly shows a wide range of responses. No statistically significant differences existed between status of use and perceptions of the effectiveness of past education/prevention programmes.

Subjects were also asked whether they felt sufficient medical research existed to support the belief that steroids work. Users and non-users reported similar opinions, with 12 (60%) respondents admitting that sufficient medical research does exist to support this statement. Three (15 %) subjects responded as being unsure as to whether this is the case.

Figure 3 shows the distribution of responses to a related question. Respondents were asked whether sufficient medical research exists to support the belief that steroids are harmful. Chi-squared analysis shows that there is a statistically significant difference between status of use and this belief. Nine (90%)nonusers felt that sufficient research does exist, whereas seven (70%) users felt that not enough research exists to support the notion that AAS are harmful.

Table 1 provides a summary of chi-squared analysis applied to this and each additional core independent variable.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This section is composed of two subsections. First, conclusions from the study are highlighted, from which additional hypotheses may be generated. Next, recommendations are made regarding the future design of AAS education/prevention programmes. This information is based upon the literature review as wel I as the data collected from this study.

Conclusions

Greater accessibility to AASs may increase the risk of AAS use. Conversely, a lack of availability may inhibit use of AASs.

TABLE 1: Yates' corrected chi-squared data analysis: core data

Independent variable p value Null hypothesis*

Availability of AASs' >0.10 Accept

Perception of effectiveness of nutritional

supplement >0.10 Accept

Body,image, >0.10 Accept

Knowledge of AAS laws >0.10 Accept

Perception of benefit of AAS use' <0.10 Reject

Perception of effect of drug testing

in sports >0.10 Accept

Attendance at AAS prevention/education programmes >0.10 Accept

Perception of effectiveness of AASs

prevention/education programmes >0.10 Accept

Perception that medical research has

proven that steroids work >0.10 Accept

Perception that medical research has

proven that AASs are harmful' <0.10 Reject

* The null hypothesis states that there is no association between status of use and each independent variable. The alternative hypothesis states that there is an association between status of use and each independent variable. AASs refers to anabolicandrogenic steroids. These two variables show statistical significance at an alpha level of 0.10.

The reasons given for AAS use include the enhancement of strength and isize as well as sports performance.

An awareness or fear of the alleged negative side effects of AASs are associated with non-use.

Collectively users and non-users feel that nutritional supplements are not as effective as AASs. Individuals involved in routine exercise regimens perceive themselves to be more concerned with their weight and body shape than most people of the same age and sex. This appears to be the case, regardless of status of AAS use.

Both users and non,users of AASs collectively demonstrate an awareness of the existence of laws governing the non-medical use of AASs.

AAS users appear to be uncertain as to the overall benefit and/or detriment of AAS use. Conversely, non-users generally feel that AAS use is detrimental.

Non-users, unlike AAS users, perceive drug testing in sports as being effective in discouraging AAS use.

AAS users appear to feel that sufficient medical research exists to support the belief that AASs work, but insufficient research exists to support the belief that AASs are harmful. Non-users, in contrast, appear uncertain as to whether sufficient medical research exists to support the belief that AAS work, yet they seem to feel strongly that sufficient research exists to support the belief that AASs are harmfut.

Typically users and non-users of AAS have never attended an AAS prevention/education programme, due primarily to unavailability and/or inaccessibility.

Recommendations

Create an awareness of successful past and current AAS prevention/education programmes among all potential programme administrators (e.g. teachers, coaches). Doing so will ensure the use of successful programmes.

To reduce the need and/or desire to use AASs, offer on-going educational programmes that emphasise nutrition and exercise methods conducive to the enhancement of strength, size and sports performance.

Make AAS prevention/education programmes accessible to both non-athletes and athletes, as AASs are being used by both groups.

Provide up-to-date information to the general public regarding AASs, thereby helping to reduce the spread of misinformation.

Clarify the purpose of AAS prevention/ education programmes by emphasising the reduction of misuse and abuse, rather than just use.

Evaluate all AAS prevention/education programmes by surveying attendees and measuring success through longitudinal studies. Doing so will provide a way to improve the effectiveness of future programmes.

Publicise the availability of AAS prevention/ education programmes to help increase programme enrolment.

Customise AAS prevention/education programmes to the interests and needs of the specific audience. Programmes designed for non-athletes should include information and instruction on the enhancement of body-image. Athletic-oriented programmes should focus on effective alternatives for performance enhancement.

Provide information at AAS prevention/education programmes that is easily understood by participants, thereby increasing retention of programme content.

Present AAS prevention/education programme information orally, visually, and kinaesthetically via lectures, visual aids, and an emphasis on interaction between programme participants and presenters. Doing so will ensure an increased understanding by participants.

Present all information in an unbiased fashion, thereby enabling participants to make independent, informed decisions regarding AAS.

Support and publicise rigorously conducted scientific research to determine the nature and scope of negative health consequences associated with AAS use.

Reduce efforts aimed at identifying and negatively sanctioning AAS users.

In conclusion, it must be stressed that the above find, ings and recommendations are based on a small subset of the total sample. As such, they must be regarded as preliminaryand subject to change based uponanalysis of the complete data set. We feel, however, that the findings to date are provocative and certainly worth sharing with all those interested in the problems associated with anabolic steroid misuse.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Satindra Chakravorty and Brenda Clevidence for their help with anal, ysis of the data, and Clinton Pulliam for his assistance in data collection.

Frank R. Ardito, Paul J. Goldstein, Michael S. Bahrke and Thomas P. Sattler, The University of Illinois at Chicago, Division of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, 2121 West Taylor Street, Room 553, Chicago, Illinois 60612-7260, USA

REFERENCES

Giannini, A.J., Miller, N. and Kocjan, D.K. (1991). Treating steroid abuse: a psychiatric perspective. Clinical Pediatrics 30(9),538-542.

Goldstein, P.J. (1990). Anabolic Steroids: An Ethnographic Approach. Research Monograph 102, National Institute on Drug Abuse, Rockville, MD, 74-95. Goldstein, P.J. (1992). Anabolic Steroids: A New Issue in Prevention Research. National Institute on Drug Abuse: Grant Number ROI, DA07933.