| Articles - Addiction |

Drug Abuse

Myths about the treatment of addiction

Charles P O'Brien, A Thomas McLellan

The Lancet 1996; 347: 237-40

Department of Psychiatry, VA Medical Center, University of Pennsylvania,

3900 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia PA 191046178, USA

(Prof Charles P O'Brien MD, A Thomas McLellan Ph-D) Correspondence to: Prof Charles P O'Brien

Although addictions are chronic disorders, there is a tendency for most physicians and for the general public to perceive them as being acute conditions such as a broken leg or pneumococcal pneumonia. In this context the acute-care procedure of detoxification has been thought of as appropriate "treatment". When the patient relapses, as most do sooner or later, the treatment is regarded as a failure. However, contrary to commonly held beliefs, addiction does not end when the drug is removed from the body (detoxification) or when the acute post drug= taking illness dissipates (withdrawal). Rather, the underlying addictive disorder persists, and this persistence produces a tendency to relapse to active drug-taking. Thus, although detoxification as explained by Mattick and Hall (Jan 13, p 97)' can be successful in cleansing the person of drugs and withdrawal symptoms, detoxification does not address the underlying disorder, and thus is not adequate treatment.

As we shall discuss, addictions are similar to other chronic disorders such as arthritis, hypertension, asthma, and diabetes. Addicting drugs produce changes in brain pathways that endure long after the person stops taking them. Further, the associated medical, social, and occupational difficulties that usually develop during the course of addiction do not disappear when the patient is detoxified. These protracted brain changes and the associated personal and social difficulties put the former addict at great risk of relapse. Treatments for addiction, therefore, should be regarded as being long terra, and a "cure" is unlikely from a single course of treatment.

Is addiction a voluntary disorder?

One reason why many physicians and the general public are unsympathetic towards the addict is that addiction is perceived as being self-afflicted: "they brought it on themselves". However, there are numerous involuntary components in the addictive process, even in the early stages. Although the choice to try a drug for the first time is voluntary, whether the drug is taken can be influenced by external factors such as peer pressure, price, and, in particular, availability. In the USA, there is a great deal of cocaine in all areas of the country, and in some regions the availability of heroin is widespread. Nonetheless, it is true that, despite ready availability, most people exposed to drugs do not go on to become addicts. Heredity is likely to influence the effects of the initial sampling of the drug, and these effects are in rum likely to be influential in modifying the course of continued use. Individuals for whom the initial psychological responses to the drug are extremely pleasurable may be more likely to repeat the drug-taking and some of them will develop an addiction. Some people seem to have an inherited tolerance to alcohol, even without previous exposure.' At some point after continued repetition of voluntary drug-taking, the drug "user" loses the voluntary ability to control its use. At that point, the "drug misuser" becomes "drug addicted" and there is a compulsive, often overwhelming involuntary aspect to continuing drug use and to relapse after a period of abstinence. We do not yet know the mechanisms involved in this change from drug-taking to addiction, and we are searching for pharmacological mechanisms to reverse this process.

Comparison to other medical disorders

The view of addiction as a chronic medical disorder puts it in a category with other conditions that show a similar confluence of genetic, biological, behavioural, and environmental factors. There are many examples of chronic illnesses that are generally accepted as requiring life-long treatment. Here, we will focus on only three: adult-onset diabetes, hypertension, and asthma. Like substance-use disorders, the onset of these three diseases is determined by multiple factors, and the contributions of each factor are not yet fully specified. In adult-onset diabetes and some forms of hypertension, genetic factors have a major, though not exclusive, role in the aetiology. Parenting practices, stress in the home environment, and other environmental factors are also important in determining whether these diseases actually get expressed, even among individuals who are genetically predisposed. Behavioural factors are also important at the outset in the development of these disorders. The control of diet and weight and the establishment of regular exercise patterns are two important determinants of the onset and severity. Thus, although a diabetic, hypertensive, or asthmatic patient may have been genetically predisposed and may have been raised in a high-risk environment, it is also true that behavioural choices such as the ingestion of high sugar and/or high-cholesterol foods, smoking, and lack of exercise also play a part in the onset and severity of their disorder.

Treatment results

Almost everyone has a friend or relative who has been through a treatment programme for addiction to nicotine, alcohol, or other drugs. Since most of these people have a relapse to drug-taking at some time after the end of treatment, there is a tendency for the general public to believe that addiction treatment is unsuccessful. However, this expectation of a cure after treatment is it is for other chronic disorders. The persistent changes produced by addiction are still present and require continued maintenance treatment-either psychological or pharmacological or a combination. As with other chronic disorders, the only realistic expectation for the treatment of addiction is patient improvement rather than cure. Consistent with these expectations, studies of abstinence rates at 1 year after completion of treatment indicate that only 30-50% of patients have been able to remain completely abstinent throughout that. period, although an additional 15-30% have not resumed compulsive use.

Successful treatment leads to substantial improvement in three areas: reduction of alcohol and other drug use; increases in personal health and social functions; and reduction in threats to public health and safety. All these domains can be measured in a graded fashion with a method such as the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) 7 In the ASI, a structured interview determines the need for treatment in seven independent domains. These measurements allow us to see addiction, not as an all-or none disease, but in degrees of severity across all the areas relevant to successful treatment.

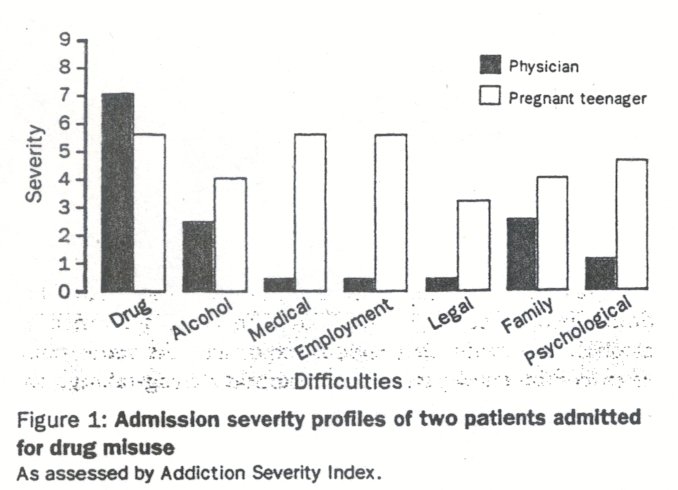

Success rates for treatment of addictive disorders vary according to the type of drug and the variables inherent in the population being treated, For example, prognosis is much better in opioid addicts who are professionals, such as physicians or nurses, than in individuals with poor education and no legitimate job prospects, who are addicted to the same or even lesser amounts of opioids obtained on the street and financed by crime. Figure 1 compares the ASI profiles of two patients admitted to our treatment programme. One was a resident physician who had few personal or professional difficulties except for heavy compulsive cocaine use. The other patient was a pregnant teenager, who was admitted while in premature labour induced by cocaine. The profile shows less drug use in the young woman, but in other areas shown to be important determinants of the outcome of treatment she has severe problems. The types of treatment needed by these two patients are clearly. different. Although the treatment of the physician will be challenging, his prognosis is far better than that of the young woman.

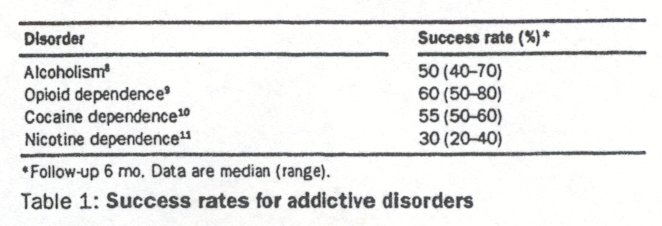

Success rates for the treatment of various addictive disorders are shown in table 1. Improvement is defined as a greater than 50% reduction on the drug-taking scale of the ASI. Another measure of the success of addiction treatment is the monetary savings that it produces. That addiction treatment is cost-effective has been shown in many studies in North America. For example, in one study in California, the benefits of alcohol and other drug treatment outweighed the cost of treatment by four to 12fold depending on the type of drug and the type of treatment.

There has been progress in the development of medications for the treatment of nicotine, opioid, and alcohol addictions. For heroin addicts, maintenance treatment with a long-acting opioid such as methadone, 1-a-acetylmethadol (LRAM), or buprenorphine can also be regarded as a success. The patient may be abstinent from illegal drugs and capable of functioning normally in society while requiring daily doses of an orally administered opioid medication-in very much the same way that diabetic patients are maintained by injections of insulin and hypertensive patients are maintained on betablockers to sustain symptom improvements. Contrary to popular belief, patients properly maintained on methadone do not seem "drugged". They can function well, even in occupations requiring quick reflexes and motor skills, such as driving a subway train or motor vehicle. Of course not all patients on methadone can achieve high levels of function. Many street heroin addicts, such as the young cocaine-dependent woman in figure 1, have multiple additional psychosocial difficulties, are poorly educated, and misuse many drugs. In such cases, intensive psychosocial supports are necessary in addition to methadone; even then, the prognosis is limited by the patient's ability to learn skills for legitimate employment..

Nicotine is the addicting drug that has the poorest success rate (table 1). That these success rates are for individuals who came to a specialised clinic for the treatment of their addiction, implies that the patients tried to stop or control drug use on their own but have been unable to do so. Of those who present for treatment for nicotine dependence, only about 20-30% have not resumed smoking by the end of 12 months.

Treatment compliance

Studies of treatment response have uniformly shown that patients who comply with the recommended regimen of education, counselling, and medication that characterises most contemporary foams of treatment, have typically favourable outcomes during treatment and longer-lasting post-treatment benefits.5, 13-16 Thus, it is discouraging for many practitioners that so many drug-dependent patients do not comply with the recommended course of treatment and subsequently resume substance use. Factors such as low socioeconomic status, comorbid psychiatric conditions, and lack of family or social supports for continuing abstinence are among the most important variables associated with lack of treatment compliance, and ultimately to relapse after treatment.1 7-19

Patient compliance is also especially important in determining the effectiveness of medications in the treatment of substance dependence. Although the general area of pharmacotherapy for drug addiction is still developing, in opioid and alcohol dependence there are several well-tested medications that are potent and effective in completely eliminating the target problems of substance use. Disulfiram has proven efficacy in preventing the resumption of alcohol use among detoxified patients. Alcoholics resist taking disulfiram because they become ill if they take a drink while receiving this medication; thus compliance is very poor.20

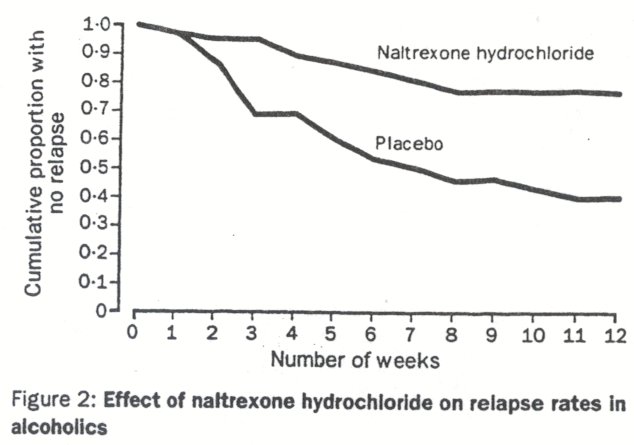

Naltrexone is an opioid antagonist that prevents relapse to opioid use by blocking opioid receptors; it is a nonaddicting medication that makes it impossible to return to opioid use, but it has little acceptance among heroin addicts who simply do not comply with this treatment. Naltrexone is also helpful in the treatment of alcoholism. Animal and human studies have shown that the reward produced by alcohol involves the endogenous opioid system. After patients are detoxified from alcohol, naltrexone reduces craving and blocks some of the rewarding effects of alcohol if the patient begins to drink again. 2 2,23 Naltrexone also decreases relapse rates (figure 2)." Although compliance is substantially better for naltrexone in the treatment of alcoholism than in opioid addiction, efforts to improve compliance are pivotal in the treatment of alcoholism. Continuing clinical research in this area is focused on the development of longer-acting forms of these medications and behavioural strategies to increase patient compliance.

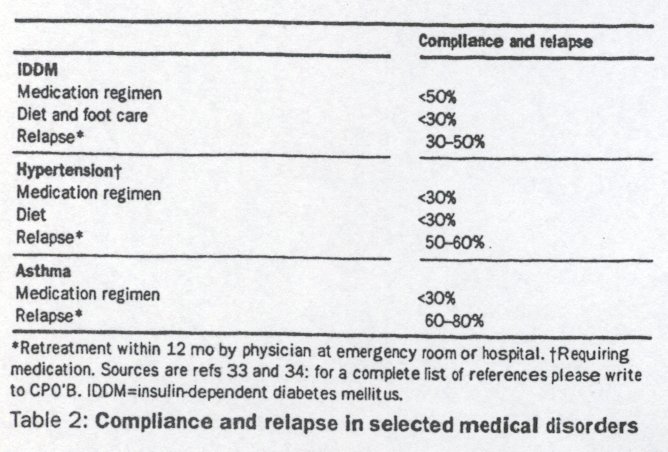

The diseases of hypertension, diabetes, and asthma are also chronic disorders that require continuing care for most, if not all, of a patient's life. At the same time, these disorders are not necessarily unremitting or unalterably lethal, provided that the treatment regimen of medication, diet, and behavioural change is followed. This last point requires emphasis. As with the treatment of addiction, treatments for these chronic medical disorders heavily depend on behavioural change and medication compliance to achieve their potential effectiveness. In a review of over 70 outcome studies of treatments for these disorders (summarised in table 2) patient compliance with the recommended medical regimen was regarded as the most significant determinant of treatment outcome. Less than 50% of patients with insulin-dependent diabetes fully comply with their medication schedule,24and less than 30% of patients with hypertension or asthma comply with their medication regimens.25 ,26 The difficulty is even worse for the behavioural and diet changes that are so important for the maintenance of short-term gains in these conditions. Less than 30% of patients in treatment for diabetes and hypertension comply with the recommended diet and/or behavioural changes that are designed to reduce risk factors for reoccurrence of these disorden. 27 ,28 It is interesting in this context that clinical researchers have identified low socioeconomic status, comorbid psychiatric conditions, and lack of family support as the major contributors to poor patient compliance in these disorders (see ref 27 for discussion of this work). As in addiction treatment, lack of patient compliance with the treatment regimen is a major contributor to reoccurrence and to the development of more serious and more expensive "disease-related" conditions. For example, outcome studies show that 30-60% of insulin-dependent diabetic patients, and about 50-80% of hypertensive and asthmatic patients have a reoccurrence of their symptoms each year and require at least restabilisation of their medication and/or additional medical interventions to re-establish symptom remission.24-26 Many of these reoccurrences also result in more serious additional health complications. For example, limb amputations and blindness are all too common consequences of treatment non-response among diabetic patients.29,30 Stroke and cardiac disease are often associated with exacerbation of hypertension.31, 32

There are, of course, differences in susceptibilty, onset, course, and treatment response among all the disorders discussed here, but at the same time, there are clear parallels among them. All are multiply determined, and no single gene, personality variable, or environmental factor can fully account for the onset of any of these disorders. Behavioural choices seem to be implicated in the initiation of each of them, and behavioural control continues to be a factor in determining their course and severity. There are no "cures" for any of them, yet there have been major advances in the development of effective medications and behavioural change regimens to reduce or eliminate primary symptoms. Because these conditions are chronic, it is acknowledged (at least in the treatment of diabetes, hypertension, and asthma) that maintenance treatments will be needed to ensure that symptom remission continues. Unfortunately, other common features are their resistance to maintenance forms of treatment (both medication and behaviour aspects) and their chronic, relapsing course. In this regard, it is striking that many of the patient characteristics associated with non-compliance are identical for these acknowledged "medical" disorders and addictive disorders; and the rates of reoccurrence are also similar.

Addiction treatment is a worthwhile medical endeavour

A change in the attitudes of physicians is necessary. Addictive disorders should be considered in the category with other disorders that require long-term or life-long treatment. Treatment of addiction is about as successful as treatment of disorders such as hypertension, diabetes, and asthma, and it is clearly cost-effective. We believe that the prominence and severity of concerns about the public health and public safety associated with addiction have made the public, the press, and public policy officials understandably desperate for a lasting solution, and disappointed that none has yet been developed. As with treatments for these other chronic medical conditions, there is no cure for addiction. At the same time, there are a range of pharmacological and behavioural treatments that are effective in reducing drug use, improving patient function, reducing crime and legal system costs, and preventing the development of other expensive medical disorders. Perhaps the major difference among these conditions lies in the public's and the physician's perception of diabetes, hypertension, and asthma as clearly medical conditions whereas addiction is more likely to be perceived as a social problem or a character deficit. It is interesting that despite similar results, at least in terms of compliance or reoccurrence rates, there is no serious argument against support by contemporary health-care systems for diabetes, hypertension, or asthma, whereas this is very much in question with regard to the treatments for addiction. Is it not time that we judged the "worth" of treatments for chronic addiction with the same standards that we use for treatments of other chronic diseases?

Supported by VA Medical Research Service and NIH/NIDA grant no P50-DA-05186. We thank Dr Debrin Goubert for her assistance with the review of medical literature.

References

1 Mattick RP, Hall W Are detoxification programmes effective? Lancet 1996;347:97-100.

2 Schuchit MA. Low level of response to alcohol. Am,J Psychiatry 1994; 151:184-89.

3 Gerstein D, Harwood H. Treating drug problems. Vol L Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1990.

4 Gerstein D, Judd LL, Rovner SA. Career dynamics of female heroin addicts. Am,J Drug Alcohol Abuse 1979; 6: 1-23.

5 Miller WR, Hester RK. The effectiveness of alcoholism treatment methods: what research reveals. In: Miller WR, Heather N, eds. Treating addictive behaviors: process of change. New York Plenum Press, 1986.

6 Armor DJ, Polich JM, Stambul HB. Alcoholism and treatment. Santa Monica, California: RAND Corporation Press, 1976.

7 McLellan AT, Luborsky L, O'Brien CP, Woody GE. An improved evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients: the Addiction Severity Index..J Nerv Ment Din 1980; 168: 26-33.

8 Institute of Medicine. Prevention and treatment of alcohol problems: research opportunities. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1989.

9 Ball JC, Ross A. The effectiveness of methadone maintenance treatment. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1991.

10 Higgins ST, Budney AJ, Bickel WK, Foerg F, Donham R Badger GJ. Incentives improve outcome in outpatient behavioral treatment of cocaine dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51: 568-76.

11 Fiore MC, Smith SS, Jorenby DE, Baker TB. The effectiveness of the nicotine patch for smoking cessation. JAMA 1994; 271: 1940-46.

12 Gerstein DR, Harwood H, Suter N. Evaluating recovery services: the California Drug and Alcohol Treatment Assessment (CALDATA). California Department of Alcohol and Drug Programs Executive Summary: Publication no. ADP94-628, 1994.

13 Moos RH, Finney JW, Cronkite RC. Alcoholism treatment: context, process and outcome. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

14 Simpson D, Savage L. Drug abuse treatment readmissions and outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1980; 37: 896-901.

15 Hubbard RI, Marsden ME, Rachal JV, Harwood HJ, Cavanaugh ER, Ginzburg HM. Drug abuse treatment: a national study of effectiveness. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989.

16 DeLeon G. The therapeutic community: study of effectiveness. Treatment research monograph 84-1286. Rockville, MD: National Institute for Drug Abuse, 1994.

17 Havassy BE, Wasserman D, Hall SM. Social relationships and cocaine use in an American treatment sample. Addiction 1995; 90: 699-710.

18 McLellan AT, Druley KA, O'Brien CP, Kron R Matching substance abuse patients to appropriate treatments. A conceptual and methodological approach. Drug Alcohol Dependence 1980; S: 189-93.

19 Alterman AI, Cacciola JS. The antisocial personality disorder in substance abusers: problems and issues. J Nerv Mental Dis 1991; 179: 401-09.

20 Fuller RK, Branchey L, Brightwell DR, et al. Disfulfmram treatment of alcoholism. JAMA 1986; 2561 1449-55.

21 O'Brien CP, Woody GE, McLellan AT A new tool in the treament of impaired physicians. Philadelphia Med 1986; 82: 442-46.

22 Volpicellf JR, Alterman AI, Hayashida M, O'Brien CP. Naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49: 876-80.

23 O'Malley SS, Jaffe AJ, Chang G, Schottenfeld RS, Meyer RE, Rounsaville B. Nahrexone and coping skills therapy for alcohol dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49: 881-87.

24 Graber AL, Davidson P, Brown A, McRae J, Woolridge K. Dropout and relapse during diabetes care. Diabetic Care 1992;15: 1477-83.

25 Horowitz RI. Treatment adherence and risk of death after a myocardial infarction. Lancet 1990, 336: 542-45.

26 Dekker FW, Dieleman FE, Kaptem AA, Mulder JD. Compliance with ' pulmonary medication in general practice. Bur Rup.q 1993; 6: 886-90.

27 Clark LT Improving compliance and increasing control of hypertension: needs of special hypertensive populations. Am Heart? 1991; 121* 664-69.

28 Kurtz SM. Adherence to diabetic regimes: empirical status and clinical applications. Diabetes Edue 1990; 16: 50-59.

29 Sinnock P Hospitalizaton of diabetes. Diabetes data, national diabetes data group Bethesda MD: National Institutes of Health, 1985.

30 Herman WH, eutsch SM. Diabetic renal disorders. Diabetes data, national diabetes data group. Bethesda MD: National Institutes of Health, 1985.

31 Schaub AF, Steiner A, Vetter W Compliance to treatment. J Clin Exp Hypertension 1993; 1S: 1121-30.

32 Gorlin R Hypertension and ischernic heart disease: the challenge of the 1990s. Am Heart J 1991; 121: 658-63.

33 National Center for Health Statistics. Pubic use datarape documentation, Hyattsville, MD: The Center, 1989.

34 Harrison WH. Internal medicine. New York: Raven Press, 1993.