PART II

Opiate Addiction as a Social Problem

CHAPTER 9 THE PROBLEM IN THE UNITED STATES DURING THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

Before tracing the development of the narcotics problem in the United States, it is appropriate to consider briefly the broader historical aspects of the problem. Morphine and heroin are derivatives of opium developed during the nineteenth century, but the history of opium itself and of its use by man begins at least several thousand years before the birth of Christ.

Mesopotamia is believed to have been the original home of the opium poppy. The Sumerians, who settled there in 5000 or 6ooo B.C., developed an ideogram for opium.(1) This ideogram has been translated as HUL GIL, the HUL meaning "joy" or "rejoicing." Methods of obtaining opium from the poppy were about the same then as they are now. The cultivation of the poppy and the use of opium spread from Mesopotamia to other parts of the ancient world. The Greeks, Romans, Persians, and Egyptians became acquainted with the drug. Homer mentioned it in the ninth century B.C. Arab traders are believed to have introduced it into the Orient, which is now the principal source .(2)

In as much as opium was used as a remedy for human ills even before the Christian era and constituted the main therapeutic agent of medical men for more than two thousand years (through the nineteenth century),(3) it is not surprising that the people of the East, where the poppy is grown, should have suffered more than their share from addiction. Nor is it unusual that for a long time opium addiction was regarded in the West as something peculiar to the Orient.

In 1804, Friedrich Wilhelm Adam Serturner, a German chemist at Einbeck, discovered in opium meconic acid and an alkaline base which he named morphium This discovery, which marked the beginning of modern alkaloidal medicine, gave great impetus to the development of the type of drug addiction which was to prevail in the West. Other opium alkaloids and derivatives were developed in rapid succession, often in the hope or belief that the new compounds would be free from the habit-forming propensities of previous ones. The climax was reached with the isolation of heroin, or diacetylmorphine, in 1898. This was the last opiate preparation to be hailed by medical men as a non-habit-forming substitute for opium or morphine or as a cure for drug addiction. Heroin turned out to be approximately three. times as powerful as morphine (which was more potent than opium) and just as habit-forming.

While Orientals have, in general, persisted in smoking opium or using it orally, another tendency has appeared among them in recent decades as a consequence of efforts made to stamp out smoking. The West, returning favor for favor, has supplied the East with hypodermic needles and with more potent opiates, particularly morphine and heroin. As it becomes more difficult for Chinese addicts to continue their smoking habits it is to be expected that the hypodermic needle will become more popular among them and that they-like the addicts of the United States -will become "vein shooters."

( Thomas DeQuincey's Confessions of an English Opium Eater, published in 1821, set the style and provided the terms which dominated discussions of opiate addiction for many decades thereafter. DeQuincey drank his opium in the form of laudanum. As a result of his widely read work, addicts were called "opium eaters," regardless of the manner in which they consumed the drug, except that opium smokers were apparently never so designated. The users of morphine, who began to appear in increasing numbers in the 1820's and 1830's, were also referred to as 11 opium eaters."

It is popularly believed today that most addicts are criminals or derelicts prior to addiction. As we have seen, this impression requires considerable qualification as it applies to contemporary drug users. It is even more inaccurate with respect to the opium eaters of the nineteenth century. In 1889 B. A. Hartwell solicited opinions from druggists in 18o Massachusetts cities concerning the economic and social status of the addicts they knew. Twentytwo per cent of those who replied said addicts were to be found in all classes, another 22 per cent said that the tipper classes were principally involved, 3 per cent named the middle classes, and only 6 per cent the lower classes. (4)

Addiction during the nineteenth century, except opium smoking, was not linked tip with crime to any appreciable extent. There are a few references to the use of laudanum by prostitutes, but it was not suggested that women became prostitutes because of the drug. The principal stress was placed upon the vice of opium eating among the respectable classes rather than among criminals. W. R. Cobbe said in 1895 that those who drank laudanum, swallowed gum or powdered opium, or used morphine were for the most part intelligent and respectable members of society. He also pointed out that they purchased their supplies of the drug openly and legally in the drugstores .(5)

Surveys conducted before the passing of the Harrison Act in 1914 invariably indicated that women addicts outnumbered men by about three to two. For example, in 1878 Orville Marshall found that 62.2 per cent of a sample of 1,313 cases in Michigan were women, (6) and L. P. Brown in 1914 found 66.9 per cent of a group of 2,370 Tennessee addicts to be women .(7) Current statistics based upon samples obtained from law enforcement agencies always show a vast preponderance of males. Other portions of the population in which the incidence of addiction was relatively high, and probably still is, were ex-soldiers and the medical and allied professions.Addicts experienced no difficulty in obtaining their drugs in those days; in fact, narcotics were almost forced upon them. Not only did the drugstores sell the supplies cheaply and openly, but all kinds of opiatecontaining patent medicines were advertised. Thus the addict of the nineteenth century had unlimited sources of supply. He could buy paregoric, laudanum, tincture of opium, morphine, Winslow's Soothing Syrup, Godfrey's Cordial, McMunn's Elixir of Opium, or many other preparations. For a few cents a day he could keep himself loaded. He could even obtain opium by purchasing the so-called cures, widely promoted during the period. Virtually all such remedies contained opiates and were merely examples of quackery.

A narcotics user once flatly asserted to me: "If a junkie tells you he got on to the stuff through his doctor, spit in his eye." The addict of today does not ordinarily become initiated through medical treatment. However, most opium eaters of the last century did, in fact, form the habit through medical treatment or by self-medication. One of the most informative books (8) on drug addiction in the nineteenth century cites more than a hundred cases of addicts who uniformly contracted the habit as a result of medical treatment. Terry and Pellens (9) quote numerous concurring opinions on this point before 1900. Little emphasis was placed on the effects of evil association, and dope peddlers were not mentioned because they were rare or nonexistent.

The public then bad an altogether different conception of drug addiction from that which prevails today. The habit was not approved, but neither was it regarded as criminal or monstrous. It was usually looked upon as a vice or personal misfortune, or much as alcoholism is viewed today. Narcotics users were pitied rather than loathed as criminals or degenerates-an attitude which still prevails in Europe.

The sharp contrast between the former public attitude and the present one is well illustrated by the case of the physician who contended in 1889 that it was obviously better to be a drug addict than a drunkard and therefore advocated that chronic alcoholics be cured by transforming them into drug addicts. He published the following statement on this question in a reputable medical journal:

The only grounds on which opium in lieu of alcohol can be claimed as reformatory are that it is less inimical to healthy life than alcohol, that it calms in place of exciting the baser passions, and hence is less productive of acts of violence and crime; in short, that as a whole the use of morphine in place of alcohol is but a choice of evils, and by far the lesser. To be sure, the populace and even many physicians think very differently, but this is because they have not thought as they should upon the matter.

On the score of economy the morphine habit is by far the better. The regular whiskey drinker can be made content in his craving for stimulation, at least for quite a long time, on two or three grains of morphine a day, divided into appropriate portions, and given at regular intervals. If purchased by the drachm at fifty cents this will last him twenty days. Now it is safe to say that a like amount of spirits for the steady drinker cannot be purchased for two and one half cents a day, and that the majority of them spend five and ten times that sum a day as a regular thing.

On the score, then, of a saving to the individual and his family in immediate outlay, and of incurred disability, of the great diminution of peace disturbers and of crime, whereby an immense outlay will be saved the State; on the score of decency of behavior instead of perverse deviltry, of bland courtesy instead of vicious combativeness; on the score of a lessened liability to fearful diseases and the lessened propagation of pathologically inclined blood, I would urge the substitution of morphine instead of alcohol for all to whom such a craving is an incurable propensity. In this way I have been able to bring peacefulness and quiet to many disturbed and distracted homes, to keep the head of the family out of the gutter and out of the lock-up, to keep him from scandalous misbehavior and neglect of his affairs, to keep him from the verges and actualities of delirium tremens and horrors, and, above all, to save him from committing, as I veritably believe, some terrible crime that would cast a lasting and deep shadow upon an innocent and worthy family circle for generation after generation. Is it not the duty of a physician when he cannot cure an ill, when there is no reasonable ground for hope that it will ever be done, to do the next best thing-advise a course of treatment that will diminish to an immense extent great evils otherwise irremediable? ...

The mayors and police courts would almost languish for lack of business; the criminal dockets with their attendant legal functionaries, would have much less to do than they now have-to the profit and well-being of the community. I might, had I time and space, enlarge by statistics to prove the law-abiding qualities of opium eating peoples, but of this anyone can perceive somewhat for himself, if he carefully watches and reflects on the quiet, introspective gaze of the morphine habitue and compares it with the riotous devil may-care leer of the drunkard.(10)

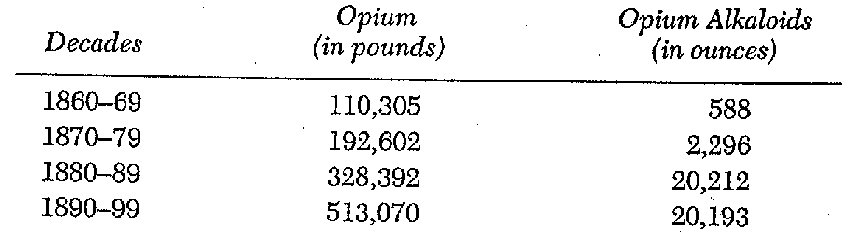

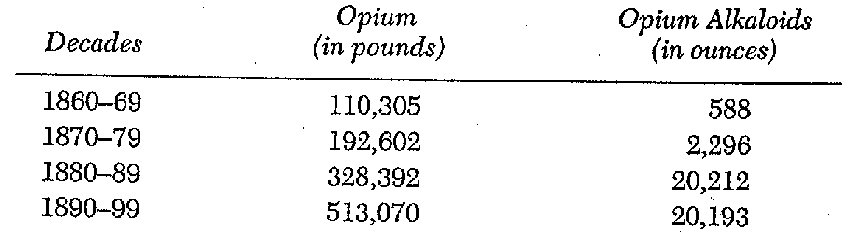

The consumption of opiates increased enormously, far outdistancing the growth of population, during the last half of the nineteenth century. Since there was relatively little illicit traffic, the following figures on the importation of opiates give a fairly accurate picture of the enormous increase in consumption of this drug during the last four decades of the last century:

After 1900 there was a drop in these totals, but it is probable that the illicit traffic was on the increase, since local restrictive legislation was becoming more frequent. In 1909 a federal law was passed prohibiting the importation of opium for smoking. The figures in the above table represent an increased use of opiates in medical practice and in the production of patent medicines as well as an increased prevalence of addiction.

In contrast with the opium eater, who was regarded simply as the victim of an unfortunate vice, the American opium smoker was typically considered, as H. H. Kane said, "a sporting character." Kane made a careful attempt to trace the development of the habit.

The first white man who smoked opium in America is said to have been a sporting character named Glendenyn. This was in California in 1868. The second induced to try it by the first-smoked in 1871. The practice spread rapidly and quietly among this class of gamblers and prostitutes until the latter part of 1875, at which time the authorities became cognizant of the fact and finding, upon investigation, that many women and young girls, as also young men of respectable family, were being induced to visit the dens, where they were ruined morally and otherwise, a city ordinance was passed forbidding the practice under penalty of a heavy fine or imprisonment, or both."(11)

Kane quotes from a letter written by a doctor of Virginia City, Nevada:

"Opium smoking had been entirely confined to the Chinese up to and before the autumn of 1876, when the practice was introduced by a sporting character who had lived in China, where he had contracted the habit. He spread the practice amongst his class, and his mistress, a woman of the town, introduced it among her demi-monde acquaintances, and it was not long before it had widely spread amongst the people mentioned and then amongst the younger class of boys and girls, many of the latter of the more respected class of families. The habit grew very rapidly until it reached young women of more mature age, when the necessity for stringent measures became apparent, and was met by the passing of a city ordinance."(12)

Considerable numbers of Chinese arrived in the United States during the 1850's; there were thousands in the West by 186o. (13) It seems incredible, therefore, that no white man should have tried the drug before 1868. An addict who began to smoke opium while he was in the West in 1906 told me that, although he had heard about the account given by Kane, he was disposed to regard it as legend. At any rate, the denizens of the American underworld acquired the habit from the Chinese, who taught them the ritual and the technique and at first supplied the drug. The Chinese influence upon the use of narcotics is evident in many words in the addict's argot. (14)

According to Kane:The very fact that opium smoking was a practice forbidden by law seemed to lead many who would not otherwise have indulged to seek out the low dens and patronize them, while the regular smokers found additional pleasure in continuing that about which there was a spice of danger. It seemed to add zest to their enjoyment. Men and women, young girls, virtuous or just commencing a downward career, hardened prostitutes, representatives of the "hoodlum" element, young clerks and errand boys who could ill afford the waste of time and money, and young men who had no work to do were to be found smoking together in the back rooms of laundries in the low, pestilential dens of Chinatown, reeking with filth and overrun with vermin, in the cellars of drinking saloons, and in houses of prostitution.(15)

The San Francisco Chronicle of July 25, 1881., stated that "the habit in past years, so far as whites are concerned, was confined to hoodlums and prostitutes mostly." It added, "Now that there are scores of places where the habit can be contracted in clean rooms in respectable portions of the city, the practice will gradually extend up in the social grade."(16)

The rapidity with which the opium-smoking habit spread was noted by an anonymous writer in Chambers' journal in 1888:

In 1877 and 1878 when Deadwood, the Metropolis of the Black Hills, one of the richest mining camps ever discovered in the United States, was over 300 miles from the nearest railroad, it was ascertained that the Chinamen had introduced the vice of opium-smoking among the white inhabitants. I was employed at the time as deputy sheriff, and received instructions to investigate the subject with a view to closing the houses and punishing the proprietors.(17)Action taken by local authorities was apparently not very effective, for former smokers state that as late as 1910 they were able to travel almost anywhere in the West without taking along either a supply of opium or an opium pipe, depending solely upon the dens that operated in almost all sizeable towns.

The opium smoker of the nineteenth century belonged to an elite underworld group which despised and generally avoided all contact with the hypodermic user or "opium eater" of respectable society. Smokers usually regarded the hypodermic habit as more vicious and difficult to break than the smoking habit. They applied the term "dope fiend" to those who used the drug in some manner other than smoking, but did not apply it to themselves. Their attitudes were indicated by an incident that occurred early in the twentieth century in a New York opium-smoking joint. One of the smokers discovered a hypodermic user in the bathroom giving himself an injection. He immediately reported to the proprietor that there was a "God-damned dope fiend in the can." The offender was promptly ejected.

Unlike opium eating, the smoking habit did not involve contact with the medical profession, for doctors did not prescribe it. Hence, the habit spread solely through contacts with persons who were already addicted, and this is the manner in which drug addiction in the underworld has continued to spread. A special committee of investigation appointed in 1918 by the Secretary of the Treasury stated: "with respect to the addict of good social standing, the evidence obtained by the committee points to the physician as the agent through whom the habit is acquired in the majority of cases."(18)

It thus appears that the association between addiction and crime in the United States was built up as a consequence of the rapid spread of opium smoking in the underworld during the last decades of the past century. Considerable notoriety and public attention was directed toward this problem. The fact that many thieves and rascals were opium smokers gradually led the public to the belief that all addicts were thieves or rascals and that there was an inherent or necessary connection between the use of opiates and a life of crime. As a matter of fact, the principal reason for the American addict's criminality is not connected with the effects of the drug as such, but rather with the high cost of the drug. In India where there is much addiction but where opium is inexpensive, there is relatively little criminality among addicts."(19)

2. Ibid., pp. 55-57.

3. Ibid., P. 58.

4. "The Sale and Use of Opium in Massachusetts," Annual Report of the Massachusetts Board of Health (1889), 22: 137-58.

5. W. R. Cobbe, Doctor Judas, A Portrayal of the Opium Habit (Chicago: S. C. Griggs, 1895), P. 127.

8. Alonzo Calkins, Opium and the Opium Appetite (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1873).

9. Terry and Pellens, OP. cit., PP. 94-110.

10. J. R. Black, "Advantages of Substituting the Morphia Habit for the Incurably Alcoholic." Cincinnati Lancet-Clinic (1889), 22: 537-41.

11. H. H. Kane, Opium Smoking in America and China (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1882), P. 1.

12. Ibid., P, 3. 14. See Glossary. 16. Ibid., p. i i.