PART I The Nature of the Opiate Habit

CHAPTER 3 HABITUATION AND ADDICTION

That morphine or some other opiate may be given to a patient over a long period of time without creating an independent craving is confirmed by many scientific reports. In a study of morphine use among ex-soldiers, Friedrich Dansauer and Adolf Rieth found many had been using the drug regularly for years, sometimes more than five, but were, nevertheless, not addicted. These users are designated as the "symptomatic type," and are not classified with true addicts, who are called "the idiopathic type." Classifying 240 of their cases in the former category, the authors give representative summaries of about 20. (2)

In the more recent literature, the distinction with which we are here concerned has been made by differentiating between drug users and drug addicts. Chein and his associates, for example, remark:

It was not until this book was well under way that it dawned on us that even a person with a history of drug use and physiological dependence on the drug might conceivably not be an addict. Such a person might be lacking in what we now regard as an indispensable characteristic of a true addict-craving, that is, a powerful 1 desire for the drug independent of the-degree to which the drug has insinuated itself into the physiological workings of his body.(3)

In the discussion that follows, the term "habituation" will be used to refer to the state of the person who is physically dependent on the drug but not addicted to it. The term "addiction" will be reserved for those individuals who have the characteristic craving, whether it be in the form in which it is manifested during regular use or as it exists in the abstaining addict impelling him to resume use. An unconscious patient or one who is given morphine regularly by attendant nurses without his knowing it could thus be described as habituated but obviously not as addicted.

Terminological confusion has been increased in the current literature by the introduction of a variety of new terms and redefinitions of old ones. "Habituation" is, for example, sometimes taken to refer to the regular use of a drug like marihuana which does not produce physical dependence as the opiates do. It has been suggested that, because there is ambiguity in the meaning of the terms "addict" and "addiction," the awkward and even more ambiguous terms, "drug abuse" and "drug abuser" be substituted for them. Some writers refer to "opiate-directed behavior" or to "sustained opiate-directed behavior," rather than to "drug use" and "drug addiction." A standardized terminology would be highly desirable, of course, but is not likely to be adopted. Confusion can be avoided only by paying attention to the substantive distinctions rather than to the terminology in which they are expressed.

In any inquiry the subject matter to be investigated must be defined and described as exactly as possible. This description is usually found at or near the beginning of the study even though the definition itself is to a large extent the result of the research. The distinction between habituation and addiction must be made by describing and enumerating those characteristics of the behavior of addicts which are unique and common and which do not occur among non-addicts. It is particularly necessary that a definition of addiction take into account the similarities and differences between habituation and addiction and sharply differentiate between them.

As already indicated, the most obvious characteristic of, the addict's behavior is his intense desire and striving for the drug. This desire is not casual or vague but is a powerful conscious motive driving him to seek satisfaction in the face of almost insuperable obstacles and at the cost of unbelievable sacrifices. A universal aspect of the behavior of addicts is that they permit little or nothing to stand between them and the drug. It would be ridiculous to speak of an addict who wanted drugs but was un aware of the need around which virtually all of his behavior was organized.

Another characteristic of the addict, and one that is as universal as the first, is his tendency toward relapse. Once addiction is confirmed, the craving acquires an -independent status; the desire persists even after the original physiological conditions have disappeared. In other words, when the addict's supply is cut off and he has been treated for withdrawal symptoms, he may be restored to apparent health, but he still tends to relapse. Were it not for this, addiction would obviously be no great social problem. It would only be necessary to separate the addict from his source of supply and then release him. Yet, in the vast majority of cases, the cured addict apparently returns to his old habit.

There is a belief prevalent among addicts that it is a misnomer to speak of a cure for addiction. They remark, "Once a junkie always a junkie." They admit that now and then an addict may refrain absolutely from using the drug for years, even though it is available, and that others do not use it for long periods of time simply because, either as a result of incarceration or for other reasons, they cannot get it. These cases are not regarded as cures, however, for the habitue knows only too well from bitter personal experience that the so-called cured case is merely one in which the regular use of the drug has been temporarily discontinued. The number of cases accessible for study in which an individual has voluntarily abstained from the narcotic for a period of years is small.

Most of the addicts whom I interviewed said that they either knew of no users who bad voluntarily refrained from using drugs for more than five years or that they knew of one, two, or a few who bad. All believed that the impulse to relapse was permanent and ineradicable. Some argued that even those few addicts who manage to abstain for long periods could probably be induced to relapse by skillful propaganda over a day or two. Relapses have been known to occur after more than ten years of abstinence.

These expressions of opinion by drug users must be discounted to some extent to allow for the addict's rationalizations. The self help organization known as Synanon is made up of former users, and many of them have abstained from drugs for considerable periods. There is also some indication that with advancing age the user's periods of abstention become longer and that some may quit permanently. In a study of former residents of Kentucky who had been at the Lexington Hospital for addicts it was found that more than half were not using drugs when they were interviewed. This fact was determined by analysis of a urine specimen from each of them. Many of these abstainers succeeded in staying off by moving to small localities where there was no illicit traffic and where they knew of no other users .(4) Such abstainers obviously would not be known to active urban addicts All the evidence suggests that the relapse rates for those addicts who go from institutions to the metropolitan centers where addiction is concentrated are much higher than those reported in the Kentucky study.While there are undoubtedly some drug addicts who voluntarily and permanently renounce their habits, the matter of eradicating the impulse to relapse poses another and different issue. The same one arises with respect to alcoholics, of whom it is said that they cannot become casual or social drinkers no matter how long they abstain. Similarly, once an individual has been booked on opiates his attitudes toward the drug are permanently changed and resumption of the habit after long periods of abstinence is easy.

The temporarily abstaining addict is a familiar figure to other addicts, who have themselves usually tried unsuccessfully to break their habits. The users are all too well aware of the boredom of non-use, and they know the rationalizations that the unhappy cured addict uses to seduce himself into a resumption of his habit. Such abstainers are not viewed as "squares" or non addicts, but simply as addicts who happen at the moment to be off drugs. The abstainer himself, like the reformed alcoholic who joins Alcoholics Anonymous, thinks of himself, not as a "non addict" but as an "ex-addict." Having joined the fraternity of those who have been booked, be feels a continuing bond that unites him with others who have had the experience and a communication barrier between him and those who have not bad it. It is in this sense that addiction may be called incurable.

In contrast to the voluntary abstainer, the user whose habit is interrupted by a prison sentence is obviously in a very different category and is usually simply called an addict and regards himself as such. The imprisoned addict commonly connives and schemes to smuggle drugs into the prison and makes his keepers acutely aware that he is different from the other inmates. To a warden of a penitentiary it would seem absurd to argue that an addict ceases to be that whenever he is off drugs. Hence, in this discussion I shall simply use the term "addict" to refer to anyone who has been booked.

There are few reliable general statistics on relapse among American drug addicts, and estimates can be made only by indirect means. A careful study of about 8oo German addicts led to the following findings: 81.6 per cent of the cures were followed by relapse within a year, 93.9 per cent within three years, and 96.7 per cent within five years. It seems probable that the relapse rate among American addicts may be even higher because of the predisposing circumstances in which "cured" American addicts usually find themselves. Moreover, relapse can take place after more than five years of abstention, so that even the remaining 3.3 per cent noted above could scarcely be regarded as cured, in the sense that the impulse to replapse bad been permanently eradicated. On the other hand, it should be observed that some of the addicts who relapsed soon after being withdrawn may well have quit again before the end of the five years. Had the authors determined how many of the 8oo were not using drugs at the end of the five-year interval the percentage would have been substantially higher than 3.3 per cent and the picture would have seemed more hopeful.(5) Because of the addict's propensity to resume his habit it is argued that progress in breaking the habit should be measured in terms of man-hours or days off drugs, rather than simply by whether relapse does or does not occur. The apparently higher rate of abstention among older addicts may mean that older users abstain more often or for longer periods than do the younger ones.

In a review of eleven studies of relapse among American addicts O'Donnell notes that the reported relapse rates varied from a low of 8 per cent over a five-year interval to a high of about go per cent over an interval of from one to 4.5 years. He notes that most of the studies focus on whether relapse occurred and do not provide information concerning the actual percentages of the time interval during which the addicts were not using drugs. When the problem is posed in this way, O'Donnell observes that the prospects appear more hopeful and that there appears to be a tendency for older addicts to abstain more on the average than is the case with younger ones. Relapse rates also are related to the addict's status during the period of study. For example, if he is on parole and threatened with reincarceration if he relapses, relapse is likely to be inhibited. The lowest relapse rate of only 8 per cent over a five-year period was secured with physicians who were assured of losing their licenses to practice medicine if they relapsed. Virtually all of the 8 per cent who did relapse under these circumstances committed suicide.(6)

Whatever the relapse rates may be for various categories of addicts, it is agreed by all who have studied them in any part of the world that relapse rates are high and that the impulse to relapse is probably permanent and ineradicable. Periodically in the past, special techniques of curing addicts have been announced with claims of an extraordinarily high percentage of cures. In no known instance have such cures turned out to be of any special significance. In some instances they were simply frauds; in others the apparent success hinged upon the brevity of the follow-up period or upon careless methods of determining whether the cured patient was actually off drugs. Clearly the word "cure" may be used in a variety of senses. It is sometimes used merely to indicate that the addict has been taken off drugs. It may also be used to indicate voluntary abstention for periods of time varying from a few weeks or months to five or more years, and it may be used to refer to the elimination of the desire or temptation to relapse. If any addict who abstains voluntarily for a period of several weeks is said to be cured, then one can say of most long term users that they have been cured many times. If, on the other hand, one reserves the term for those in whom the desire for drugs has been permanently eradicated, it is doubtful if there are any cured addicts.

The practical problem of controlling addiction, of course, is to promote abstention whenever this is possible. Theoretical interest is more focused on the nature and origin of the craving for drugs than on attempting to understand and explain the peculiar persistence of this craving when the drug has been removed. Similar problems exist with respect to smoking, alcohol addiction, and other habits which are periodically renounced and easily resumed.

Mere drug use without addiction, which we designate here as habituation, does not involve the tendency to relapse which is so Characteristic of the addict. Patients who use or take morphine to the point of physical dependence do not, as has been indicated, necessarily become addicted. When they do not, the discontinuance of the drug does not predispose them to resume its use unless, of course, the pain or disease for which it was being used recurs. The contrast may best be brought out by the consideration of a number of cases of habituation, keeping in mind the behavior of the addict in similar circumstances. Dansauer and Rieth report the case, for example, of a patient who was given an opiate regularly from 1922 to 1927; when the drug was withdrawn the patient was weak and unable to work for seven months, after which he resumed his activities. These investigators do not classify this man as a genuine addict. Similar cases are reported elsewhere in the same treatise .(7) In all instances, the drug had been used daily for several years, yet the conclusion was that since these patients showed none of the craving typical of addicts they could not be considered addicts.

The outstanding characteristics of these cases are that the use of the drug was related to painful and chronic disease and that upon withdrawal the patient had no desire for the drug, nor did he resort to it except when the disease recurred. Then, too, drug craving as expressed verbally and as manifested in the devices and chicanery employed by addicts to obtain narcotics was absent. These cases are no more distinctive or unusual than hospital patients to whom other types of medicine have been given with good results.(8)

The work of Dansauer and Rieth has been emphasized here because of the long period of time during which opiates were administered to their subjects (in some instances for more than ten years) without inducing a state of addiction. Although the time factor involved in similar cases known to me was less crucial, the situation on the whole was essentially the same. For example, a patient who bad received the drug for two months suffered considerable distress when it was withdrawn, without knowing the reason until the nurse later explained it. When he heard that I was studying drug addiction, be expressed amazement that one could become addicted to morphine. He bad felt absolutely Do desire for it when the morphine treatment was suspended. All the cases of habituation interviewed in the present study conform to this pattern.

In summary, then, there are two principal aspects of addiction which distinguish it from non-addiction and from habituation. First, the addict desires the drug continuously, intensely, and consciously. Second, this craving, once established, becomes independent of the physiological conditions of tolerance and physical dependence, and predisposes the individual to return to the drug even after a lapse of years. The chronic user in prison, for example, often looks forward eagerly to his release and upon his discharge usually loses little time in securing an injection. He learns in advance exactly where to go to get his shot in the briefest possible time. The desire for the drug in such cases has become an independent psychological complex. (9)

There is still another difference between the addict and the individual who for a time is merely the passive recipient of the drug. The former, while under the influence of the drug, is constantly aware of his dependence on it, and attributes his state of mind to its effects.(10) The latter, on the other hand, receiving the drug unknowingly in connection with illness, cannot analyze its precise effects, even though he is under its influence and dependent upon it physiologically. In describing a cancer patient habituated to morphine, Bernhard Legewie reports that the drug obviously stimulated the sufferer and made him feel better. However, the patient failed to associate the beneficial effects with the injection, so that instead of desiring the drug he came to dislike it. According to Legewie, "the lack of desire for the drug in our patient was striking.(11) This attitude may be contrasted with that of the typical addict, whose point of view was well expressed by J. C. Layard, himself an addict. After a period of abstinence, be resumed taking the drug, and reported: "I now liked to work, the harder and the more of it, the better. The morphine has such a bracing and tonic effect! I felt when I walked as though I bad a man on each side of me, supporting me. (12)

Dependence upon morphine or other opiates in the case of addicts is particularly emphasized when the drug is withdrawn. Craving for the drug and dependence upon it drive the user almost irresistibly to any lengths to obtain a supply. A writer, himself an addict, states that he knew of two suicides resulting from failure to secure drugs: "The awful mystery of death, which they rashly solved, had no terrors for them equal to a life without opium, and the morning found them hanging in their cells glad to get 'anywhere, anywhere out of the world."' The same writer describes a Chinese addict whom be saw "tear his hair, dig his nails into his flesh, and with a ghastly look of despair, and face from which all hope had fled and which looked like a bit of shriveled yellow parchment, implore for it [opium] as if for more than life."(13)

The addict, of necessity, organizes his entire life around his need for the drug. This preoccupation with the narcotic and slavish dependence upon it are incomprehensible both to the patient who is only habituated and to the neophyte. As Calkins observed, "Opium, an equivocal luxury in the beginning, daintily approached, becomes ere long under the demands of perverted appetite a dire alternative, a magisterially controlling power."(14) The hospital patient who every four hours is given an injection, the nature of which he does not know and concerning which he does not trouble himself, clearly cannot be compared with the addict who is eager to sacrifice anything to obtain the same substance.

The addict, if awake, is usually keenly aware of the fact that a shot buoys him up, and he knows precisely when he must have another. He proceeds to regulate his activities almost exclusively in terms of this drive. He takes a shot when be goes to bed. Upon awakening, his first thought is of the drug, and his first act, sometimes even before be gets out of bed, is to take his morning dose. Should be awaken during the night, the thought of a shot tempts him, and if he lies awake for any length of time he is likely to yield to the desire. In other words, the addict is dependent upon the drug during every conscious moment. The thought of the drug constantly sustains him.

By contrast, the patient who is only habituated reveals a different mode of behavior. A physician told the writer of the following incident:

A woman went to a quack doctor with a stomach complaint. He gave her medicine which helped her, but in the course of time she noticed that whenever she stopped taking the medicine for a time her stomach trouble came back. Wishing to be really cured of her disease, she decided to consult another doctor. She realized that the prescription was helping her, but was troubled by the fact that (as it seemed to her) the medicine had only repressed her ailment without eliminating it. The new doctor found that the medicine contained opiates and that there was nothing whatever wrong with her except that she had become habituated to the drug.

This case is a prototype of habituation associated with physical disease, the drug being used because of actual pain associated with the disease. The important factor is obviously the patient's belief. It will be shown later that as long as a patient believes he is using the drug solely to relieve pain, and regards it as a "medicine," be does not become an addict. When the pain or disease vanishes the drug may be removed without danger of relapse.

The patient's sense of dependence on drugs in the above case was clearly different from that of the addict; her preoccupation was with a disease rather than with the effects of opiates, which she recognized only vaguely. When she swallowed her medicine, the disease seemed to be abated. In the same way, a person who has a headache and takes an aspirin knows only that his headache is gone and that a hindrance to normality has been eliminated. He does not believe that normality is dependent upon the drug. This type of opiate use has frequently been termed "innocent" addiction, and-in contrast with the exceedingly pessimistic prognosis for genuine addiction-it is usually permanently cured following withdrawal of the drug, provided the disease does not recur. T. D. Crothers, a prominent American authority, distinguishes these two types in the following manner:

Where morphine has been used ignorantly, or from a physician's prescription for the relief of some temporary pain, the permanent cure of the case may generally be expected to follow its withdrawal. ... In cases where the patient has bad a long preliminary occasional use of the drug, and then a period of protracted use until immunity to very large doses has been established, the withdrawal is always difficult, and the permanence of any cure is somewhat doubtful.(15)

Discussing the possibility of a cure for addiction, Lawrence Kolb expresses the belief that there are thousands of cured addicts in the country (though the word "cure" evidently refers here to addicts who are merely off the drug). He says: "If we class as former addicts all those persons who after several weeks of opiate medication suffered for a few days with mild withdrawal such as restlessness, insomnia, and overactivity of certain glandular functions-the number of cured addicts must exceed those who remain uncured."(16)

Another important respect in which habituation usually differs from genuine addiction is in the size of the dose and in its progressive increase. Physiological reasons for increasing the dosage are well established. For example, when morphine is administered over a period of months to a patient with incurable cancer, the dose is necessarily increased, but rarely, if ever, in the proportions that the addict finds necessary. The latter is so powerfully impelled to increase the dosage that be often regards an excess as essential and finds it virtually impossible to reduce it voluntarily. In therapeutic treatment, even in cases of protracted illness and pain, a daily dose of 3 or 4 grains is regarded as an extraordinary amount. The addict who has a large supply available to him regards 3 or 4 grains of morphine a day, taken in "skin shots" or orally, as a small allotment.

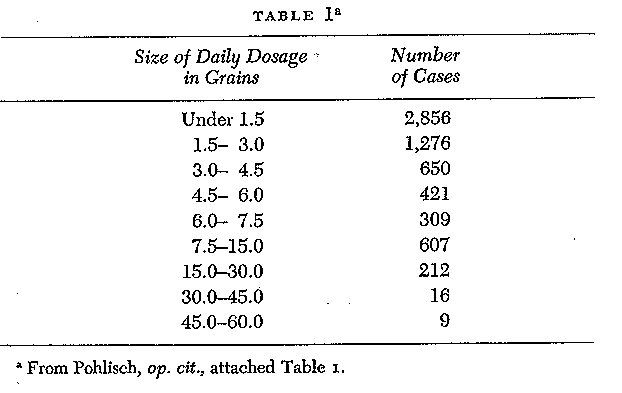

The difference between the addict's dosage and that of the patient in the condition of habituation is effectively demonstrated by data collected by Kurt Pohlisch in an attempt to determine the approximate number of drug addicts in Germany. (17) These data were taken largely from druggists' prescription blanks, and Pohlisch was therefore compelled to define addiction purely in terms of the size of the doses and the length of time during which they were taken. He was familiar with the distinctions made by Levinstein, Erlenmeyer, and others between "habituation" and "addiction," and be recognized the validity of this distinction; nevertheless, he was forced by the nature of his data to take these things into account only as they could be translated into amounts used per day. Therefore, he established the minimum dosage as 1.5 grains per day but admitted that his figure classified too many as addicts.(18) If one were to use the concept of addiction (Morphinismus) generally employed in German clinics, the limit might have been placed, he said, at 4.5 grains per day. By using a very low limit be corrected unavoidable errors in the other direction.

When his cases are distributed according to dosage, they fall into a frequency pattern which does not at all correspond to expectations concerning addicts.(19)

It will be noted that the number of patients using less than 3 grains per day is very large, about 65 per cent of the total, and that the number in each classification becomes progressively larger as one approaches the smaller doses. This, of course, contradicts general experience with addicts. Kolb found in a study of 119 cases of addiction that the average dose was 7.66 grains per day.(20) His subjects were medical cases, that is, persons who bad become addicted in medical practice, and were not of the underworld. Since the majority obtained their supplies from legitimate sources, the average dosage reported by Kolb is therefore more reliable than figures derived from the testimony of underworld addicts, who use diluted drugs, generally do not know precisely bow much they are taking, and cannot be counted upon to report it correctly if they do know. The only plausible explanation of Table i, an explanation made by Pohlisch himself, is that a high percentage of the patients using very small amounts were not addicts, and that the percentage of those who were only habituated, but not addicted, decreases as the dosage increases. This conclusion is borne out if the physicians included in the Pobliscb study are listed separately, as follows:

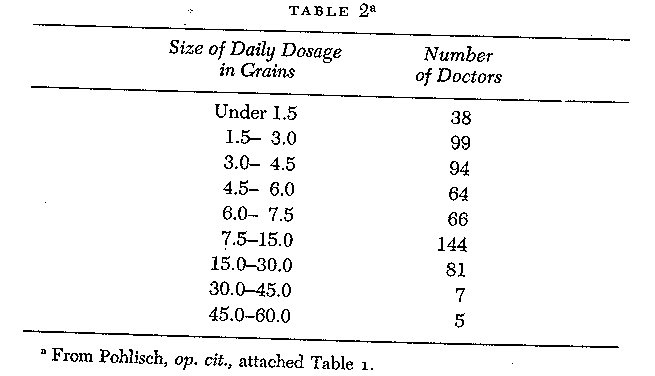

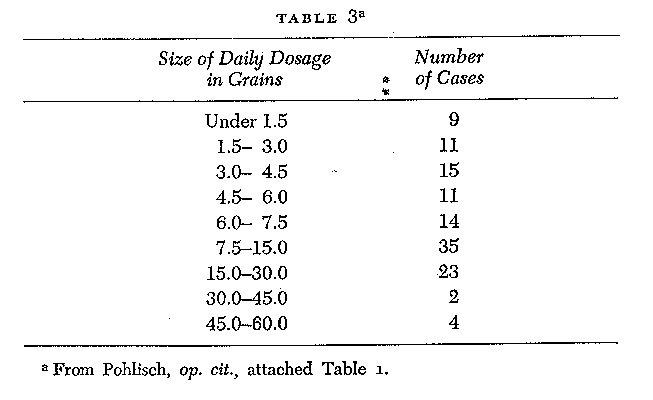

The marked concentration around the lower figures is absent in this distribution; only 22 per cent of the doctors used less than 3 grains per day. One would expect that the percentage of addicts among doctors who are regularly taking morphine would be larger than among non medical persons. Thus Table 2 corroborates the distinction made here between habituation and addiction. Further support of my thesis, that addiction and habituation are radically different, may be obtained by listing separately those cases mentioned by Pohliscb in which cocaine was used in connection with morphine, heroin, or another opiate. One could also expect most of this group to be addicts because of the relative infrequency with which cocaine is prescribed and because the use of cocaine and an opiate in combination represents a degree of sophistication ordinarily encountered only among addicts. The users of cocaine and an opiate (usually morphine) took the following amounts per day:

Only 16 per cent used less than 3 grains per day, as contrasted with 65 per cent of the total cases (including physicians and cocaine users). The distribution is again strikingly different from that of the ordinary run of cases and corresponds rather closely to general observation concerning the approximate size of the addict's dosage, as well as to the average Of 7.66 grains per day reported by Kolb for his medical cases.

The impulse to increase the dosage is so powerful that most drug users with whom I discussed the matter regarded it as almost inevitable that an addict should use too much. They were skeptical of any addict who claimed to require only as little as 2 or 3 grains per day. It may be possible by resolute determination to stabilize drug consumption at a low level, but the trend toward a progressively larger dosage is probably a distinguishing characteristic of addict behavior. There is nothing in medical practice remotely corresponding to the insatiable appetite for large doses that characterizes most chronic users. It may safely be assumed that even those addicts who manage to stabilize their intake at a low level feel the desire to use more. Again in contrast to the addict, the habituated person not only uses a smaller amount on the average but does not feel the progressive need for more. Many German addicts studied by Dansauer and Rieth, for example, obtained their narcotics from two different doctors at the same time and tried similar deceptions, while nothing of the sort occurred among those who were using the drug without being addicted. I have known a number of cancer cases in which morphine was administered orally for more than a year without reaching a maximum Of 2 grains a day, the equivalent of perhaps one grain hypodermically. Such moderation is practically unheard of among addicts, unless it is involuntary.

A final characteristic of addicts is that they know they are addicts and speak of themselves as such. American underworld addicts refer to themselves as "junkies" or "users," and are so regarded by others. Frequently, in a jocular sense, they use the more expressive term "dope fiend." Even the drug user in respectable society, who may lave few or no addicted associates, secretly labels himself a "drug addict" or "dope fiend."

The most obvious way of defining addiction or of determining if a person is an addict is to ask him, provided, of course, that one has his confidence. Another simple procedure is to inquire among those of his associates who are in a position to know. While I was gathering the material for this study, I asked individuals who had once been "booked" if they were addicts, and they always replied unhesitatingly in the affirmative, even though they were free, of the drug or bad voluntarily abstained for several years. In contrast to the addict, the hospitalized patient who has been receiving opiates to deaden pain does not regard himself as an addict. If he does not recognize withdrawal distress, he obviously cannot infer that his experience has any connection with drugs. The most striking demonstration of this point is to be found in Case 3, cited in Chapter 4. Further illustration is offered in the following case:

While in his teens, Mr. D. fell from a telegraph pole and fractured his spinal column. He was taken to a hospital and, to relieve the pain, was given a number of white pills. His back was put into a cast, and the pills were discontinued, but the family doctor continued to give him a tonic. As he gradually recovered he continued to take this medicine, but derived absolutely no pleasure from it as far as he was able to recall, nor did he have the slightest notion that it contained an opiate. He had never seen a drug addict and had no conception of what addiction was. After ten months of this treatment, he suddenly decided to leave town and go to a distant city to seek work. He had noticed, in the meantime, that whenever he did not take his medicine he did not feel well, but attributed this to his accident. When he left home it did not occur to him to take any medicine along, so that when he became ill from withdrawal distress, he had no notion of what was wrong but assumed it was disease. He tried at first to treat himself, but, when he continued to feel worse and noticed that he was losing weight rapidly, he consulted a doctor, who diagnosed his condition correctly. It was then that he realized for the first time that he had been using an opiate. He then defined himself as a drug addict and began to read all the medical books on the subject that he could find. He also increased his dosage until he reached approximately 6o grains a day. This took place before the enactment of the Harrison Act, when narcotics were easily available and inexpensive.

It is noteworthy that during the initial period of habituation in this case the behavior symptomatic of addiction was entirely absent. Then, when the true situation was brought home to Mr. D., a pronounced change occurred in his attitude toward the drug, as evidenced by his interest in reading about it. It should also be observed that when this turning point was reached the dosage was rapidly increased.

Addiction may be defined as that behavior which is distinguished primarily by an intense, conscious desire for the drug, and by a tendency to relapse, evidently caused by the persistence of attitudes established in the early stages of addiction. Other correlated aspects are the dependence upon the drug as a twenty four-hour-a-day necessity, the impulse to increase the dosage far beyond bodily need, and the definition of one's self as an addict. This complex of behavior will hereafter be referred to as 11 addiction," and the organism which exhibits it will be called an ,,addict." The term "habituation," on the other hand, will be used to refer to the prolonged use of opiates and to the appearance of tolerance and withdrawal distress, when it is not accompanied by the behavior described above as addiction behavior.

It is evident from the above discussion that an animal cannot be called an "addict," regardless of how much opiate drug it is given. Johannes Biberfeld correctly expresses the relationship of animal experimentation to, and its bearing upon, the problem of drug addiction when he asserts that addiction involves two types of phenomena, tolerance for morphine and a craving for morphine, and that only the former has any connection with animal experimentation. The craving, he believes, is an exclusively human phenomenon and animal behavior cannot be compared with it.(21) While recent experimentation with lower animals has narrowed the gap between human and animal responses to opiates by inducing in lower animals some interesting parallels with the behavior of human addicts, the gap has by no means been closed and Biberfeld's conclusion is still essentially correct. The more cautious of the contemporary experimenters with lower animals recognize this and do not claim that their animal subjects exhibit the same behavior that a human subject does. This experimental work with lower animals will be considered in more detail in a later chapter.

The physiological conditions produced by the drug when it is habitually assimilated by the body are essential to addiction, but other factors are also present, for the physiological conditions are not always followed by addiction. The problem of the present study, then, narrows down to that of isolating the factors which account for the transition from a biological condition, induced by regular drug administration for a period of time, to a psychological state of addiction or craving. Undoubtedly the physiological concomitants play a role in addiction, for certainly no one becomes an addict without first experiencing them. Any explanation of addiction must, therefore, consider these phases, but it must also take the psychic aspects into account. The theory proposed in this study must also account for the fact that some persons escape addiction while others, under essentially the same physiological condition, become incurable addicts. In other words, the physiological factors must be regarded as necessary concomitants of addiction but they are not causal in the sense that they "produce" such behavior. In subsequent chapters, the conditions which lead to the transformation of mere drug use or habituation into addiction will be specified and described. The theory that will be developed assigns an essential but not a determining role to the biological aspects of addiction.

Some students of addiction from the biological sciences insist that addiction ought to be defined in biological or biochemical terms and sometimes equate it with physical dependence. Such a definition is clearly unacceptable for one who studies the behavior of the addict since it would require that infants born of addicted mothers be called addicts while drug users locked up in jail could not be. As has been shown in this chapter, physical dependence may exist without addiction and addiction without physical dependence. If one is interested solely in the bodily effects of opiates it is certainly legitimate and necessary to study the phenomena of physical dependence and tolerance, but if one is concerned with the social psychology of addiction, that is, with behavior, the definition of addiction must be in behavioral terms.

If it is argued that the regular use of opiates produces permanent organic or biological changes which form the basis of the craving and of the relapse impulse, then it is necessary to assume that the same effects must be produced in countless hospital patients who unknowingly receive morphine and exhibit no craving whatever. To call such patients addicts is to do violence to the plain meaning of terms.

The definition of addiction that has been proposed here is one that focuses on what are believed to be essential, common, or universal aspects of the behavior of addicts. There are many other aspects of addiction behavior which occur in some addicts and not in others, and there are special forms of behavior associated with different ways of using the drug. All of these must be excluded from consideration because, being nonessential differences between the instances, they cannot form the basis of a sound definition and they are not of central theoretical relevance. A general theory of addiction must obviously be concerned with explaining the central core of common behavior, not the peripheral and idiosyncratic variations which sometimes occur and sometimes do not. Neither can a sound definition of addiction include any element of moral judgment such as an assertion that it involves the illegal use of drugs or that it is harmful to the individual or the society. Persons dying of cancer who are provided with liberal quantities of morphine by their physicians may be addicted in the same essential sense that any other person may be.

The definition proposed is one that is designed to apply to addicts anywhere, whether they use the drug intravenously, by inhalation, by smoking, by drinking it, or any other way. It distinguishes especially between those who are merely physically dependent on the drug and those who are psychologically dependent on it in the special sense implied by the word "addiction." One hypothetical qualification might perhaps be made. If one could imagine a society in which addiction carried absolutely no stigma and in which opiates were freely available to users, it is reasonable to suppose that the addict's preoccupation with maintaining his supply would not be as strong or as continuous as it has been described here. Much of the American user's anxiety and preoccupation stems from the scarcity of the supply and the difficulties in obtaining it and might be compared with attitudes toward food during a famine. In a hypothetical society made up entirely of addicts in which drugs were abundant and food scarce, no doubt the central preoccupation would be with food rather than with drugs.

2. Friedrich Dansauer and Adolph Rieth, "Ueber Morphinismus bei Kriegsbeshadigten, Arbeit und Gesundheit: Schriftenreihe zum Reichsarbeitsblatt (1931), 38: 23. Cf. also Kurt Pohlisch "Die Verbreitung des chronischen Opiatsmissbrauchs in Deutschland," Monatschrift fur Psychiatric und Neurologie (1931), 79 (1): 1-32. C. E. Terry in Report to the Committee on Drug Addictions on the Legal Use of Narcotics in Detroit, Michigan, and Environs for the Period July 1, 1925, to June 30, 1926 (New York: Bureau of Social Hygiene, 1927), P. 18, notes that "patients suffering from chronic painful maladies and taking large doses of morphine or other opium equivalents were said by their physicians not to be addicted."

3. Isidor Chein, Donald L. Gerard, Robert S. Lee, and Eva Rosenfeld, The Road to H: Narcotics, Delinquency and Social Policy (New York: Basic Books, 1964), PP. 5-6.

5. Dansatier and Rietb, op. cit., p. 59.

7. Dansauer and Rietb, op. cit., case no. 588, -p. 96; see also pp. 92, 94, and 97.

8. See ibid., p. 97, for authors' description of these cases.

12. James C. Layard, "Morphine," Atlantic Monthly (1874), 33: 705,

13. "Sigma," "Opium Eating," Lippincott's Magazine (April, 1868), 1: 409.

14. Alonzo Calkins, Opium and the Opium Appetite (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1871), P. 188.

15. T. D. Crothers, Morphinism and Narcomanias from Other Drugs (Phil adelpbia: W. B. Saunders, 1902), P. 138.

16. Quoted by Terry and Pellens, op. cit., p. 616.

21. Johannes Biberfeld, "Zur Kenntnis der Morphingewohnung. 11, Ueber die Spezifizitat der Morphingewohnung," Biochemische Zeitschrift (1916), 77: 283. See also S. D. S. Spragg, "Morphine Addiction in Chimpanzees," Com parative Psychology Monographs (1940), 15: 120 ff. Spragg agrees with Biberfeld's statement concerning experiments other than his own. It is my opinion that Biberfeld's observations also apply to Spragg's work.