CHAPTER 2 THE EFFECTS OF OPIATES

A nondrinker engaged in the 'study of alcoholics might deliberately get drunk once himself in order to understand his subjects better. There are, however, two excellent arguments for not doing this in the case of opiates. First, the effects of a small amount of drugs upon a non-addict are in almost no sense comparable to their effects upon an addict; indeed, in many respects, they are quite the opposite, and the difference not only is one of degree but is definitely qualitative as well. Second, the experiment would be too dangerous. Under normal circumstances a man can deliberately make himself drunk and can be none the worse when he recovers. But it is doubtful whether anyone can use morphine long enough to acquire the same experiences as an addict without himself becoming one.

Since the first injections of morphine which a non-addict receives are usually gratifying, either in a positive sense or because of the relief from pain afforded, it is the popular impression that the pleasure of the addict must be immensely greater, especially in view of the enormous sacrifices that he makes to keep himself supplied with the drug. Plausible as this notion seems, it is nevertheless fallacious.

The effect of opiates upon the human organism constitutes a problem for physiologists and biochemists. We are here concerned mainly with the question of how the physiological and psychological effects of the drug are perceived by the addict.

Initial Effects

The first effects of injections of opiates administered to non addicts are, as we have said, usually but not always pleasurable. The sensation or experience varies greatly depending upon the person, the setting, the mood of the user, and the size of the dose and the manner in which it is taken. The intravenous method of use produces the sharpest and most noticeable impact. In some instances, as Becker has reported with respect to marihuana, the beginner experiences effects which he does not recognize as being associated with the shot, no doubt because he anticipated something else.(1) Sometimes, even in the case of individuals who later become addicted, the initial injections may produce unpleasant sensations such as headache, dizziness, and nausea. There are also some persons who appear to have something like an opiate allergy, so that the drug, even with repeated use, does not produce pleasurable feelings but leads instead to increasing discomfort and distress. Such persons are very rare. They do not, of course, become addicted.

To the average person, however, the first dose may bring sleep, or it may, especially if it is small, stimulate him to extra activity or mental effort. Under different circumstances the same person will be variously affected, even though the dose is of the same strength. When the subject is depressed or fatigued the effects of a small dose are usually much more noticeable then when be is normal and in good spirits. In fact, the more closely he approximates a normal condition, the less likelihood there is of his noticing any reaction at all when be takes the first dose.

The learning processes involved in the first trials of the drug are illustrated by incidents related to me by addicts. For example, a man who experimented with opiates in the presence of two addicts reported that be felt nothing except nausea, which occurred about half an hour after the injection. It took a number of repetitions and some instruction from his more sophisticated associates before this person learned to notice the euphoric effects. In another instance an individual who complained that she felt nothing from two closely spaced injections amused her addicted companions by rubbing her nose violently while she made her complaints. A tingling or itching sensation in the nose or other parts of the body is a common effect of a large initial dose.

Experiments made by Beecher (2) with non-addicted subjects who were given injections of various kinds of drugs, including heroin, along with placebos, provide a more sober perspective on initial effects of opiates than that which is often projected in the popular literature. Beecher's subjects did not know what particular drug they were given nor did those who received placebos know this fact. All were asked to report on the degree of pleasure or displeasure they felt after being given what they supposed to be a drug. Those who received placebos reported greater pleasure than those who were given heroin. This result may well have been produced by the unpleasant initial effects that sometimes occur and to which allusion has already been made. It is of interest that the addict redefines such effects as desirable and welcomes them because they are indications to him of good quality drugs.

The disagreeable effects that sometimes accompany the first few trials of the drug ordinarily disappear after a few or several repetitions of the dose. There then follows in most cases what has been called a "honeymoon" period during which the person on his way to addiction increases the size of his dose and for a time experiences a more intense euphoria. The latter has often been described in the popular literature. It appears to consist largely of a subtle feeling of being at home in the world and at peace with it. The effect is more marked if the individual is depressed, fatigued, or troubled when be takes his shot.

One of my addicted subjects commented as follows on the drug's effects:

Contrary to the belief entertained by many, if not most, a dose or a series of doses of opium derivatives does not produce a supernormal state. It does not produce the ability to do things better, to think or reason with greater clearness than would be possible without the drug. It is true that in some conditions of mind or body, and perhaps during the short initial period of addiction, the drug will seemingly lift one up to a state where the perceptibilities are sharpened, where the senses are better able to cope with any given situation than would be the case without drugs. But a careful analysis of the condition of the individual would usually elicit the fact that he was considerably below par, in some respect, before he took the drug. All that it has done is to restore him to a normal, or nearly normal, state of mind and body.

Opiates do not produce spectacular or uncanny states of mind like those attributed to LSD. There are no hallucinations, waking dreams, illusions, or other psychotic-like effects associated with them. Popular writers have sometimes attributed such effects to heroin and other opiates probably because they have been influenced more by literary stereotypes or a desire to create a dramatic effect than by the actual testimony of addicts. The latter too is often colored by the user's craving for the drug, which leads him to retrospective exaggeration. Friedrich Chotzen observed in 1902:

Nearly all authors agree that the chronic abuse of morphia in contra-distinction to other poisons gives rise to no special psychosis. . . . When mental disturbances occur in chronic users of morphine, these are referred for the most part to contemporary complicating poisoning by other poisons, especially alcohol, chloral hydrate, and cocaine.(3)

Along similar lines, Lawrence Kolb observed in 1925:There is no destruction of protoplasm such as follows prolonged excessive use of alcohol. Neither nerve cells nor fibers degenerate; consequently, the drug cannot produce diseases analogous to Korsakoff's psychosis, acute hallucinosis, or alcoholic multiple neuritis, and hospitals for the insane have remarkably few cases diagnosed as drug psychoses. Such psychoses are so rare that one is led to suspect that case 7-2 is typical of most of those that do occur. [This was a case of the use of cocaine and morphine in combination.(4)

The initial effects then consist largely of a general dulling of sensibilities, accompanied by a pleasant though not sensational or uncanny state of mind which is characterized by freedom from pain and worry and by a quickened flow of ideas. It should be emphasized again that normal, healthy persons may fail to notice any initial effects whatsoever if they are not on the watch for them. As C. Edouard Sandoz has stated:

The widely spread belief that morphine brings about an uncanny mental condition, accompanied by fantastic ideas, dreams and whatnot, is wrong, notwithstanding certain popular literature on the subject. The most striking thing about morphine, taken in ordinary doses by one who is not an addict, is that it dulls general sensibility, allays or suppresses pain or discomfort, physical or mental, whatever its origin, and that disagreeable sensations of any kind, including unpleasurable states of mind &re done away with. In fact, the suppression of pain is the only outstanding effect of morphine when given for that purpose. The more normal a person feels, the less marked, as a rule, the effects will be."(5)

Naturally, the evaluation of the first effects of opium will vary in accordance with the character of the individual. Thus a sensitive man, with certain neurotic ailments, may be tremendously impressed with the soothing qualities of the drug, and by contrast with his usual state of mind, may feel intense pleasure. On the other hand, a prosaic and stolid person, with no sense of strain or conflict, may be wholly unaffected.(6)

A good account of the most common initial effects was given by Louis Faucher, who experimented on himself while preparing a thesis on morphinism at the medical college of the University of Montpellier.(7)

He took one dose each day for six days, stopped for fifteen days, and then repeated the experiment. He wrote:

The initial effects were pleasant.... Then, for a brief moment I noticed a feeling of unusual well-being; my bed was more pliable, the objects in my room seemed more familiar, my body seemed lighter. I also had at the same time two unpleasant experiences.... Then when everything became silent again I began to experience the euphoria of morphine. It made the night sweet for me; I can scarcely express in any other way the subtle pleasure that I experienced. It is true I noticed nothing extraordinary; I had no illusion or hallucinations. My breathing was easier and freer. I thought about my personal affairs, my work and my dislikes. Things that had seemed difficult now seemed easy. Some of the problems of real life appeared to me in a new guise, with their solutions perfectly obvious.... It was nothing. It was scarcely noticeable. But it was good.(8)

The regular administration of opiates, extending over a period of time, creates a physiological need for its continuance. Once habitual use is stopped, a number of distressing symptoms appear, increasing in severity in proportion to the period of addiction and depending upon the size and frequency of the dosage. In fact, no matter why the drug was first taken, its continued use leads to a periodic, artificially produced depression and distress which disappear immediately upon repetition of the dosage. After about three weeks of regular daily use, the abstinence symptoms apparently increase at an accelerated tempo and rapidly become very severe and even dangerous. A discussion of almost any aspect of the drug habit invariably involves a consideration of these withdrawal symptoms, which are uniquely associated with the use of opiates. Animals and infants, as well as adults who unwittingly receive drugs, suffer withdrawal symptoms which are similar to those of the addict. This fact demonstrates that the distress is not "imaginary" but is based upon disturbances of organic functions. A. B. Light, E. G. Torrance, and their co-authors have provided an excellent chronological account of the withdrawal symptoms accompanying the discontinuance of opiates, based on observation and experimentation with American underworld addicts who submitted themselves for cure at the Philadelphia General Hospital. They described the behavior of their patients during withdrawal as follows:

As the time approaches for what would have been the addict's next administration of the drug, one notices that he glances frequently in the direction of the clock and manifests a certain degree of restlessness. If the administration is omitted, he begins to move about in a rather aimless way, failing to remain in one position long. He is either in bed, sitting on a chair, standing up, or walking about, constantly changing from one to another. With this restlessness, yawning soon appears, which becomes more and more violent. At the end of a period of about eight hours, restlessness becomes marked. He will throw himself onto a bed, curl up and wrap the blankets tightly around his shoulders, sometimes burying his head in the pillows. For a few minutes he will toss from side to side, and then suddenly jump out of the bed and start to walk back and forth, bead bowed, shoulders stooping. This lasts only a few minutes. He may then lie on the floor close to the radiator, trying to keep warm. Even here he is not contented, and he either resumes his pacing about, or again throws himself onto the bed, wrapping himself under heavy blankets. At the same time he complains bitterly of suffering with cold and then hot flashes, but mostly chills. He breathes like a person who is cold, in short, jerky, powerful respirations. His skin shows the characteristic pilomotor activity well known to those persons as "cold turkey." The similarity of the skin at this stage to that of a plucked turkey is striking. Coincident with this feeling of chilliness, he complains of being unable to breathe through his nose. Nasal secretion is excessive. He has a most abject appearance, but is fairly docile in his behavior. This is a picture of his appearance during the first eight hours.

Often at the end of this period the addict may become extremely, drowsy and unable to keep his eyes open. If he falls asleep, which is often the case, he falls into a deep slumber well known as the "yen" sleep. It takes unusual noises to awaken him. The sleep may last for as long as eight or twelve hours. On awakening, he is more restless than ever. Lacrimination, yawning, sneezing, and chilliness are extreme. A feeling of suffocation at the back of the throat is frequently mentioned. Usually at this stage, the addict complains of cramps, locating them most frequently in the abdomen, but often in the back and lower extremities. A right rectus rigidity with pain localized over the appendical region is not uncommon; one can easily be misled in the diagnosis, since at this stage a leucocytosis is frequently present. Vomiting and diarrhea appear. He may vomit large quantities of bile-stained fluid. Perspiration is excessive. The underwear and pajamas may become saturated with sweat. Muscular twitchings are commonly present; they may occur anywhere, but are most violent in the lower extremities. He may sit in bed with his leg flexed, grasping it tightly below the knee, fearing the twitch will suddenly throw it into a complete extension which be cannot control. If he is handed a cigarette to smoke, his hands tremble so violently that he may have difficulty in placing it in his mouth. The tremor is so marked that he is unable to light it himself. He refuses all food and water, and frequently sleep is unknown from this point. It is at this stage that he may one minute beg for a "shot" and the next minute threaten physical violence. Nothing can make him smile. He will beat his head against the wall, or throw himself violently on the floor. Any behavior which he thinks will bring about the administration of the drug will be resorted to. Occasionally he may complain of diplopia. Seminal emission in the male and orgasms in the female frequently occur.

We believe that the height of these withdrawal symptoms is reached somewhere between the period of forty-eight hours and seventy-two hours following the last dose of the drug taken. The readministration of the drug promptly brings about a dramatic change. The patient becomes exceedingly docile almost with the puncture of the hypodermic needle. in a few minutes he begins to feel warm, and the goose flesh and perspiration are no longer visible. He speaks about a "heaviness" in his stomach, but regards this as a welcome symptom presaging relief. In a period ranging from thirty minutes to one hour the tremors disappear. He has become strong and well. He no longer walks with bowed head and stooped shoulders. He stands erect, is quite cheerful, and lights his cigarette like any normal person. He becomes profuse in his apologies for his conduct during the abrupt withdrawal of the drug.(9)

Mild withdrawal symptoms appear after a very few injections provided that the injections are sufficiently large and are spaced close enough to each other to produce a cumulative effect. As use continues, it becomes necessary, if the withdrawal symptoms are to be prevented from appearing, to increase the amounts taken and to take more doses per day. As the withdrawal symptoms become more intense, the effects of the injections that eliminate them become correspondingly more pronounced. In the earliest stages of use both withdrawal distress and euphoria may be so slight as to go unnoticed. With repeated and increased doses both the distress and the euphoria are greatly increased; the latter particularly by the fact that it is augmented by relief of withdrawal. Eventually, as will be indicated later, the positive euphoria obtainable from the drug diminishes or vanishes, leaving the addict with two main sources of gratification: (i) relief of withdrawal symptoms and (2) impact effects that are felt immediately after an injection for a period of perhaps five to ten minutes.

According to Sandoz, the continued administration of morphine causes the following changes in initial effects:

The duration of the effect of the morphine is shortened. Whatever untoward effects were present at the beginning disappear. The same dose will become less and less effective, or must be increased in order to obtain the same effect. More than this, the original feeling of unusual well-being can no longer be obtained; under the influence of morphine the chronic user will simply feel "normal."(10)

In the beginning phases of addiction, the pleasurable effects of drugs, other than those that occur at the time of injection, tend to diminish and vanish. As this occurs, and as withdrawal distress increases, the psychological significance of the doses changes. Whereas they at first produced pleasure, their primary function becomes that of avoiding pain, that is, withdrawal. The addict seems to continue the use of the drug to avoid the symptoms which he knows will appear if he stops using it.

This change or reversal of psychological effects appears to have its counterpart on the bodily level, for here too the effects of morphine and heroin upon the addict are very different from and in some respect the opposite of what they are on the non-addict. In the latter the first effects of the drug are to produce disturbances of normal bodily functions. With continued administrations as tolerance and physical dependence are established, most but not all of these disturbed functions seem to return to normal or nearly so. A new body equilibrium or "drug balance" is established and is upset only or primarily when the drug is stopped. Many biologically oriented investigators have noted this fact and pointed to the necessity of distinguishing between opiate effects observed in non-using subjects and those found in addicts. Erlenmeyer, a German investigator, wrote as follows on this point:

The continued administration of morphine exerts an entirely different effect on a morphinist from that exerted by a single medium dose of morphine injected into a healthy person. While this latter causes nausea, even vomiting, feeling of faintness, heart weakness, pulse acceleration and lowering of the blood pressure, the former occasions just the opposite feelings, sensations and states ... namely pleasant feeling, euphoria, increased power, and, in the heart and vessels, strengthening of the contraction, invigoration of the pulse, and rise of the blood pressure. Since every morphinist has once had the first morphine injection, there arises the question: by what means and at what time of the continued abuse does this reversal of effect take place? Is it brought about as follows: The morphine, originally foreign to the body, becomes an intrinsic part of the body as the union between it and the brain cells keeps growing stronger; it then acquires the significance and effectiveness of a heart tonic, of ail indispensable element of nutrition and subsistence, of a means of carrying on the business of the entire organism. . . . This reversal does not occur abruptly, but very, very gradually. If morphine is withdrawn before this reversal, the abstinence symptoms do not appear."(11)

Although Erlenmeyer's apparent assumption that the initial effects of morphine arc always or usually unpleasant may be incorrect, his main point is one that has been made in one form or another by many investigators. Amsler, for example, argued that morphine has two effects on a nontolerant individual: a narcotic or depressing one which lasts a relatively long time and is followed by a short period of stimulation. As addiction progresses, the stimulating phase gradually becomes dominant and reduces and finally eliminates the depressing phase. (12)

An explanation or theory, of addiction cannot be based on the first effects of the drug on the beginner if these effects are reversed or vanish when addiction is established. Moreover, the initial effects of the drug may never be experienced at all by a hospital patient who is unconscious and they may be unnoticed by other patients who are seriously ill or in great pain. Addiction may nevertheless follow from these circumstances and from any others that involve regular use or administration over a sufficient period of time. The theoretical problem posed by addiction is therefore altogether separate and distinct from that of accounting for the initial use of drugs. Since an unconscious person may have drugs administered to him to the point of establishing physical dependence, it appears that mere use of drugs does not constitute a unitary or homogeneous pattern of behavior which could be accounted for by one general theory applicable to all such use. The central theoretical problem of addiction concerns, not the initial use, but the continued, voluntary and regular use of drugs after physical dependence has been built up.

Taking regular, closely spaced doses (for example, four hours apart), the beginner soon notes a feeling of slight depression before each shot, and a vague depletion of energy signaling the beginning of the withdrawal symptoms. Following the injection, his energy is revived, his efficiency, both mental and physical, is restored, and he is again prepared to go about his ordinary affairs. An injection delayed beyond the usual time will bring greater relief, varying according to the depression preceding it. Various methods of administering the drug produce different effects. For example, intravenous injection brings an intense physical thrill, sometimes compared by the addicts to sexual ecstasy. The sensation is momentary. On the other band, oral use of opiates causes a gradual transition of feeling tone, with relief as the primary sensation. Some addicts find pleasure in making the puncture with the needle, and in playing with the injection; others who are "needle-shy" find the puncture distasteful and may avoid using the needle altogether.

Addicts almost invariably assert that, apart from the physical impact of injections, they feel "normal" or "usual" under the drug's influence. At the same time, with apparent inconsistency, they also extravagantly praise its effects upon them. To say that one feels normal is, of course, not entirely the same as saying that one is normal. American addicts, for example, are chronically afflicted by constipation, their appetites for sex and food are commonly reduced, and they have much more tooth decay than does the general population. Mortality rates of addicts are not exactly known, but they are undoubtedly high. These are items of which addicts are well aware, and they have many other troubles besides. When they say they feel normal they refer to a state of mind, not to the state of their bodies, their finances, or their social relations.

In the above sense, there is only one authoritative source on how a given addict feels, and that is the addict himself. The tendency of the outsider who learns about addiction from the mass media is to assume that the drug user who sacrifices so much and undergoes so many deprivations and miseries for the sake of his habit must obtain an extraordinary euphoria from it-in other words, that the drug must make him feel very extraordinary indeed. The idea that addicts experience uncanny psychological pleasures and live a life of ecstasy is false on the face of it and is denied by them. Their denial must be accepted unless evidence can be produced to discredit it. Available evidence, however, tends to confirm the user's view.

For example, it is conclusively established that under appropriate circumstances addicts can be deceived into believing that they are receiving drugs and are under their influence when in fact they are not. They may also be led to believe that they are not under the influence of drugs when they in fact are. An illustration is provided by a gradual reduction method of curing addicts that has been practiced in this country and that has also been used elsewhere. These cures involved gradual reduction of dosage with saline solution substituted gradually for the drug until after a period of time (such as two weeks) the patient was being given only saline and no drugs at all. In some of these systems the injections were continued on a regular basis for a -period of time after complete withdrawal of the drug bad been effected. The addicts, who were not told what the program was, often thought they were still getting drugs after it had been discontinued and others thought they were off drugs when in fact they were still receiving substantial doses.

I have interviewed ex-patients who sheepishly admitted that such deception had been successfully practiced on them for as long as ten days. One addict said that he knew of two women who had received water or saline for an entire month under the impression that it was morphine. It is also reported that addicts who demand drugs for insomnia can sometimes be put to sleep with a sterile hypodermic if they believe it is morphine. Conversely, when they have been given a morphine injection and have been told that it was a non-opiate drug, they may continue to complain. Instances of this kind have been so generally noted in the literature and reported so often by addicts that the possibility of such deception must be considered an established fact.

Dr. Charles Schultz performed an experiment in which half of a group of subjects were put on a seven-day reduction treatment, and the other half on a fourteen-day schedule; for the former, the daily dose was reduced by one-seventh, and for the latter by one fourteenth.(13) As a result, some patients on the fourteen-day schedule thought they were receiving the seven-day treatment, and after the expiration of seven days began to show great nervousness and restlessness, one subject even resorting to an apparently simulated convulsion. When it was explained to them that they had been put on a fourteen-day course, and that they were still getting half of their beginning dosage, all symptoms disappeared at once. (14) A similar illustration is furnished by a former addict, a soldier who was wounded at the front and lay unconscious in a hospital for several days. Opiates were freely administered to him, but when he regained consciousness he did not realize that he was under the influence of drugs until the characteristic and unmistakable distress of withdrawal appeared.

In a personal communication to me, a physician reported that a woman patient about to undergo a painful operation had asked him not to administer opiates under any circumstances, explaining that, although an abstainer, she had once been addicted and that a single injection might cause a relapse. Even if it were a matter of life and death, she begged that no opiates be given her, The doctor agreed, but after the operation the patient suffered such intense pain that a narcotic prescription became absolutely necessary, and was administered orally disguised in liquid form. It made the patient more comfortable and relieved the pain. Since she was not aware that she had received the opiate there was no relapse into the former habit. Later she thanked the doctor for his support of her program of abstinence.

R. N. Cbopra and his collaborator performed an ingenious experiment along the same lines. They disguised opium by administering it in oil of citronella as "tonic number X" to patients in a Calcutta hospital who complained of pain and demanded relief.'(15)" This device revealed the malingering addict, for be always continued to complain after the opium bad been taken, while nonaddicts admitted that they felt relieved.

The absence of a distinctive or unusual state of mind produced by the drug is clearly revealed by another interesting phenomenon. The addict's common complaint during a cure of the gradual reduction type, is not that he suffers from withdrawal, but that be cannot "feel the shots." When such a point is reached many addicts demand that the drug be discontinued entirely, preferring not to prolong the suspense; since they cannot feel the injections, they may as well not take them. In commenting on this attitude, Schultz observes:

When they reach the end of the reduction, with complete withdrawal, there is not the same reaction of euphoria as after abrupt withdrawal, for several reasons. First, they are never really sure that they are getting less than they should anyway, and, in fact, they are always in a paranoid, suspicious state thinking they are not getting a square deal. They believe they are being fooled by sterile hypodermics and resent this idea because they often think they can detect when no more narcotics are given them, although they actually do not. When they are still getting opiates they sometimes believe they are getting sterile water (they call it "aqua" or "Swanee River" or "onion juice"); and, vice versa, they often think they are getting morphine when plain saline is given them."(16)

One addict reported to me that he had been similarly deceived in a hospital, and that when he discovered it he left at once, resenting "their making a fool of me." He had been getting sterile hypodermics for ten days and was feeling quite well until an attendant, whom he had bribed to find out how much morphine he was getting, disclosed the truth. Instances of this kind are quite common. Indeed, it is remarkable that veteran addicts who have run the gamut of experiments with the drug can be deceived about its effects. Needless to say, individuals who have not bad, previous experience are much more readily and completely deceived. The patient who receives therapeutic drug treatment, or who becomes dependent upon morphine, does not ordinarily report anything more than relief from pain. If he has withdrawal symptoms, the latter are usually identified as symptoms of his disease, the after-effects of surgery, and so on.

It seems evident that opiates do not produce an uncanny or extraordinary state of mind. In fact, if incidental events which serve as signs of the drug's presence are manipulated, the injection itself cannot even be recognized. In other words, nearly all the direct effects of the drug which last beyond a few minutes after the shot are such that they could easily be attributed to other causes if they appeared in isolation. Knowing that he is addicted, the addict ascribes his mental changes to the drug, not because they are recognizable as such but because they always accompany the shot. The characteristic impact of the drug, coupled with the changes in feeling tone intimately associated with the injection, assures him that it was an opiate and nothing else. In addition, the withdrawal symptoms inevitably remind him of the need for a further supply. When all these incidental aspects of addiction are taken out of his control, the patient becomes uncertain of his feelings, and the psychological satisfaction derived from the belief that he is receiving morphine may closely simulate the cyclic changes that occur with actual injections. During an abrupt withdrawal, without substitute medication, it is quite impossible to deceive an addict into believing that his distress is due to any cause other than a shortage or absence of opiates in his system, It will be noted that all deception involves the suppression of the drug's physical impact and the absence of pronounced withdrawal symptoms. When either of these two factors is clearly identified, deception is no longer possible.

The point may be made in another way by comparing opiates with other drugs that do produce sensational and spectacular effects, such as LSD. It is impossible to imagine an LSD user going on a "trip" without realizing it, or experiencing the LSD effect from eating a cube of sugar which he erroneously believed to contain the drug.

While there has been considerable interesting research in recent years on the placebo effect in other areas, very little of it has been done with addicts or with the opiates. The unexploited possibilities of this sort of a research enterprise are suggested by certain events following World War 11. It was reported by some investigators that a new form of addiction to heroin had been found among juveniles. Its peculiarity was that it involved Do withdrawal symptoms. It later appeared that this idea was derived from the heavy dilution of the drugs sold by the peddlers, so that addicts who believed themselves to be addicted were in fact using such a heavily diluted product that the), were not getting enough to maintain physical dependence. Some of these users were themselves surprised and humiliated, when, after claiming to have big habits, they experienced little distress upon withdrawal. The peddlers bad, in effect, administered a gradual reduction cure without their customers realizing it!

The addict's claim that he feels normal under the influence of drugs obtains further support from the fact that the study of the effects of opiates upon the body and bodily functions have uncovered either only minor injurious effects or none at all that can be traced directly to the drug. Allusion was made earlier to the prevalence of constipation, tooth decay, and reduced appetites among addicts. Some of these, such as tooth decay, for example, are not traceable directly to the drug. There are persons who have used drugs for long periods of time and who have no tooth decay at all. This suggests that this particular ailment is associated with some incidental aspect of the addict's way of life rather than with the drug per se. The same may be said of the depression of sex activity, since users sometimes report no such effect and may even regard the drug as an aphrodisiac.

Apart from the above considerations, if it is asked whether the regular use of drugs such as morphine and heroin produces any major bodily malfunction or destruction of tissue, the answer on the basis of available evidence must be that apparently it does not. W. G. Karr, professor of biochemistry at the University of Pennsylvania, commented as follows:

The addict under his normal tolerance of morphine is medically a well man. Careful studies of all known medical tests for pathologic variation indicate, with a few minor exceptions, that the addict is a well individual when receiving satisfying quantities of the drug. He responds to work in the normal manner. His weight is normal. His cardiac and vascular system is normal. He is as agreeable a patient, or more so, than other hospital cases. When he is abruptly withdrawn from the drug he is most decidedly a sick individual.(17)

Light and Torrance reach a similar conclusion. They observe:... morphine addiction is not characterized by physical deterioration or impairment of physical fitness aside from the addiction per se. There is no evidence of change in the circulatory, hepatic, renal or endocrine functions. When it is considered that these subjects had been addicted for at least five years, some of them for as long as twenty years, these negative observations are highly significant.(18)

In view of such typical findings, any attempt to attribute decay of "character" or of "moral sense" to the drug must be regarded as unwarranted, since there are no known physiological or neurological changes to which they may conceivably be related. Moreover, in the therapeutic administration of opiates to patients who are unaware of what they are receiving, no such results have ever been reported. In fact, the trend has been in the opposite direction. After an exhaustive review of reports on the alleged effects of opiates, Terry and Pellens in 1928 concluded: "Wherever the truth may lie, the evidence submitted in support of statements ... dealing with type predisposition and with the effects of opium use on mental and ethical characteristics is, in our opinion, insufficient to warrant the opinions expressed."(19) This Conclusion still appears valid.It was noted early in this chapter that the user who characteristically maintains that he feels normal under the drug's influence also characteristically describes the effects of the drug with great enthusiasm. This seeming inconsistency arises from the different points of reference in the two assertions. When the user says he feels normal he refers to the interval between shots, which may be taken as four hours here for illustrative purposes. The praise he bestows on the drug's effects refers to the sensations that occur when the injection is made and immediately after. These might be called "impact" effects. They may last for five to ten minutes in the case of intravenous injections. The intensity of the pleasure the addict obtains from them depends in considerable part on the intensity of distress or depression immediately preceding the shot. It is from this contrast between the way the addict feels before and the way he feels after an injection that be derives his ideas of the desirable effects of the drug. Viewed in this light the apparent inconsistency of the addict's claims vanishes and the importance which he attaches to "feeling the shot," that is, the impact effect, is made more intelligible. When I confronted addicts with the- inconsistency involved in simultaneously talking of the wonderful effects of drugs and of feeling normal under its influence, some were ready to concede that it was probably the relief of beginning withdrawal symptoms that created the favorable impression of the drug. Another idea was that it was simply a reflection of the intensity of the addict's craving; that he enjoys the drug so much because be desires it so intensely rather than because it is inherently enjoyable.

The ideas that the drug addict's inner life is serene and' untroubled, that he lives in a world of drug-induced fantasy and dreams, or that his life is dominated by ecstasy are completely false. The average American addict is in fact a worried, troubled, and harried individual. Misery, alienation, and despair. rather than pleasure and ecstasy, are the key features of his life. After the honeymoon period, the user usually feels trapped by the inexorable rhythm of his habit and the heavy demands it makes upon him. In addition, he experiences more than his share of tragedy, frustration, and misfortune and is affected by them much as other people are except that there is superimposed on his reactions the artificial cyclic rhythm of addiction. Without the drug, life may seem intolerable; with it the user feels that he is in control and that be can face his problems. Misfortunes that occur when a user is suffering from drug deprivation seem to depress him more than they should. When be has an adequate supply, the addict feels that his reactions to misfortune are more nearly what they should be, more like those of the average, normal non-addict.

It is well known that many addicts have led useful and productive lives, relatively unaffected by their habit Lawrence Kob. in a study of 119 person addicted through medical practice.. -)und that go had good industrial records and only 29 had poor ones. He comments:

Judged by the output of labor and their own statements, none of the normal persons had their efficiency reduced by opium. Twenty-two of them worked regularly while taking opium for twenty-five years or more; one of them, a woman aged 81 and still alert mentally, had taken 3 grains of morphine daily for 65 years. She gave birth to and raised six children, and managed her household affairs with more than average efficiency. A widow, aged 66, had taken 17 grains of morphine daily for most Of 37 years. She is alert mentally but is bent with age and rheumatism. However, she does physical labor every day and makes her own living.(20)After three years of observation and tests upon 453 addicts in India, Chopra found changes in personality and social behavior in only one third of the cases, and in only 3.6 per cent were these described as major changes .(21) The most usual were the acquisition of a sad expression, vacant look, bad memory, or tendency toward slow cerebration. About 6o per cent of his subjects had a healthy and normal appearance and were mentally unaffected by the habit. A notable case was that of a British army officer who, at the alleged age of 111 was said to have used opium or morphine in huge quantities for the preceding seventy years. His army career had been brilliant, and at his advanced age he was described as unusually active and alert.(22)

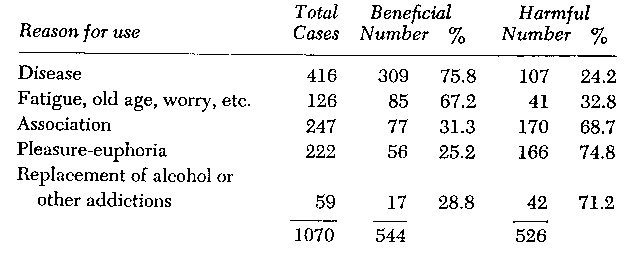

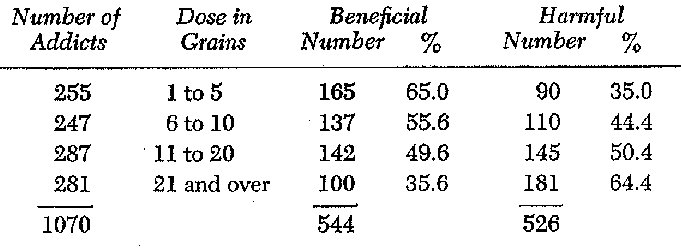

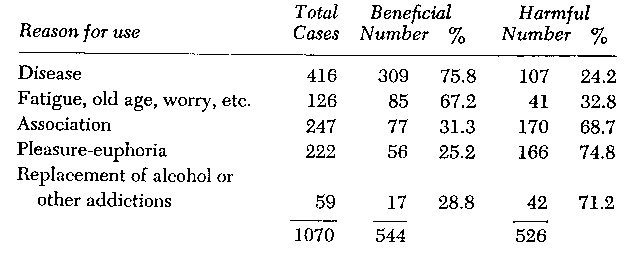

Cbopra asked 1,070 addicts whether they regarded the habit as beneficial or harmful. Grouping the cases according to the size of the daily dosage, his investigation yielded the following principal findings: (23)

Grouping the same cases according to the reason given for the original use of opium, he obtained the following results:

These data suggest that, disregarding social consequences, the effects are considered beneficial in inverse proportion to the size of the dose, and depending upon whether the drug is used to alleviate such conditions as old age, worry, fatigue, and disease, or for other reasons. This conclusion harmonizes with medical opinion. Although it may strike the reader as a paradox, the morphine habit may actually benefit particular individuals, such as the chronic alcoholic or the psychoneurotic. Drug addiction and drunkenness are incompatible vices for liquor causes the addict's withdrawal symptoms to appear sooner than usual and morphine tends to make an intoxicated man sober. Neurotic symptoms may sometimes be suppressed by the regular use of opiates. Roger Dupouy describes a woman who took morphine for hysterical Symptoms.(24) She used it for thirty years without any further seizures until the drug was removed, whereupon the paroxysms immediately returned.

The obvious deleterious effects which the drug habit usually has on the American addict's social life and personality, and even some of physical discomforts and disturbances associated with it, cannot be regarded as direct and necessary consequences of the pharmacological action of the drug. Addicts who are well-to-do or who have an assured supply of drugs often avoid these consequences. Serious "character deterioration" often makes its appearance only when the user is apprehended by the police and processed in the courts. There are vast differences between the behavior of most American addicts and those of other countries that handle the problem in different ways. The social behavior of the addict everywhere depends upon the legal and social context in which it occurs, not on the biochemistry of the drug.

Ostromislensky has appropriately remarked that "the phenomenon of morphinism seems from the outside to be a chaotic mixture of strange and apparently illogical facts, seeming nonsense and various paradoxes."(25);, If the user only succeeds in feeling normal, one is compelled to wonder why he should go on spending twenty to fifty dollars a day for this non-effect. Why, when he has been extricated from this trap, is he so strongly impelled to resume his habit? In view of his intense craving and his extravagant appraisal of the drug's effects, how can it be possible to deceive him about whether he is under its influence? In view of the catastrophic personal consequences of addiction of which the user is more keenly aware than anyone else, why does the user not feel "normal" when he is withdrawn from the drug? These paradoxical aspects of the addict's behavior make it easy to understand the popular impression that there is something sinister, mysterious, or uncanny in a drug which has such devastating effects and is at the same time such a great boon in medical practice.

Three major points emerge from this discussion. First, that the initial effects of opiates are not comparable to their effects upon an addict and are indeed, in many respects, the opposite of them. Second, the psychological effects of the drug upon the regular user, apart from the impact effects, are not sufficiently marked to provide any clue for an understanding of the power of the habit. During addiction the drug seems to function to keep the user in a psychological and physical state which is so close to what may be called normality that it is often extremely difficult or impossible to determine by simple external observation whether a given person is or is not actively using drugs. Third, the personal and social characteristics of the American addict are not directly determined by the pharmacological effects of the drug, but are consequences of the role which he is forced to adopt in our society, that is of his social, economic, and legal situation.

The reversal of effects which occurs during the process of establishing tolerance and physical dependence on opiates makes it impossible for non-addicts to share the experiences of the chronic user. The attempt to understand the addict from one or a few experiences with morphine inevitably produces only misunderstanding. The varied and paradoxical aspects of the opiate habit have long offered challenging theoretical problems to behavioral scientists and have generated theories which are about as varied, paradoxical, and inconsistent as is the behavior of addicts.

1. Howard S. Becker, "Becoming a Marihuana User," American Journal of Sociology (1953), 59: 235-42.

2. Henry K. Beecher, Measurement of Subjective Responses (New York: Oxford University Press, 1959), PP. 321-41.

4. Lawrence Kolb, "Pleasure and Deterioration from Narcotic Addiction," Mental Hygiene (1925), 9: 704.

5. Edouard Sandoz, "Report on Morphinism to the Municipal Court of Boston," Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology (1922), 13: 13.

6. It is repeatedly said that certain psychoneurotic types are peculiarly susceptible to the pleasurable effects of narcotics. See, for example, Report of the Departmental Committee on Morphine and Heroin Addiction (London: British Ministry of Health, 1926); Lawrence Kolb, "Drug Addiction in Its Relation to Crime," Mental Hygiene (1925), 9: 74-89, and "Pleasure and Deterioration from Narcotic Addiction," Mental Hygiene (1925), 9: 699-724; Paul Sollier, "Hysterie et morphinomanie." Revue Neurologique (1903), 11: 855; and Terry and Pellens, op. cit., Index entry, "psychopaths, predisposition of."

7. Louis Faucher, Contribution a l'etude du reve morphinique et de la morphinomanie (thesis, University of Montpellier, no. 8, igio-ii).

8. Ibid., p. 18 ff.9. A. B. Light, E. G. Torrance, W. G. Karr, Edith G. Fry, and W. A. Wolff, Opium Addiction (Chicago: American Medical Association, 1929), pp. 10-11. Reprinted by permission.

11. Quoted by Terry and Pellens, op. cit., pp. 6o 1-602.

12. Casar Amsler, "Ueber Gewohnung an narkotische Gifte und Entwohnung davon, insbesondere ueber Morphingewohnung und Entwohnung," Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift (1935), 48: 815-18. See also on this point Terry and Pellens, op. cit., PP. 2.33, 26o.

13. "Report of the Mayor's Committee on Drug Addiction to the Honorable R. C. Patterson, Jr., Commissioner of Correction, New York City, American Journal of Psychiatry (1930-31), 10: 509. (Hereinafter referred to as "Report of Committee on Drug Addiction to Commissioner of Correction, New York City.") A portion of this report was written by Charles Schultz.

15. R. N. Chopra and J. P. Bose, "Psychological Aspects of Opium Addiction," Indian MedicalGazette(1931), 66: 663-66.

16. "Report of Committee on Drug Addiction to Commissioner of Correction, New York City," op. cit., P. 518.

17. Unpublished speech at the Fifth Annual Conference of Committees of the World Narcotic Defense Association and International Narcotic Education Association (New York, 1932).

18. Light, Torrance, et al., op. cit., p. 315.19. Terry and Pellens, op. cit., p. 515.

20. Lawrence Kolb, "Drug Addiction-A Study of Some Medical Cases," Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry (1928), 20: 178.

21. R. N. Cbopra, "The Present Position of the Opium Habit in India," Indian Journal of Medical Research (1928), 16: 389-439.22. See "The Opium Habit," Catholic World (September, 1881), 33: 827-35.

25. Ivan Ostromislensky, "Morphinism," New York Medical Record (1935), 141: 556.