The National Council on Crime and Delinquency

Kids, Drugs, and Drug Education,

A Harm Reduction Approach

by Marsha Rosenbaum, Ph.D.

The Lindesmith Center, San Fransisco, California

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Foreword

Introduction

Drug Education in the U.S

What's Wrong with Drug

Education?

A Harm

Reduction Approach to Drug Education

Model Programs

Conclusions

Endnotes

LIST OF FIGURES

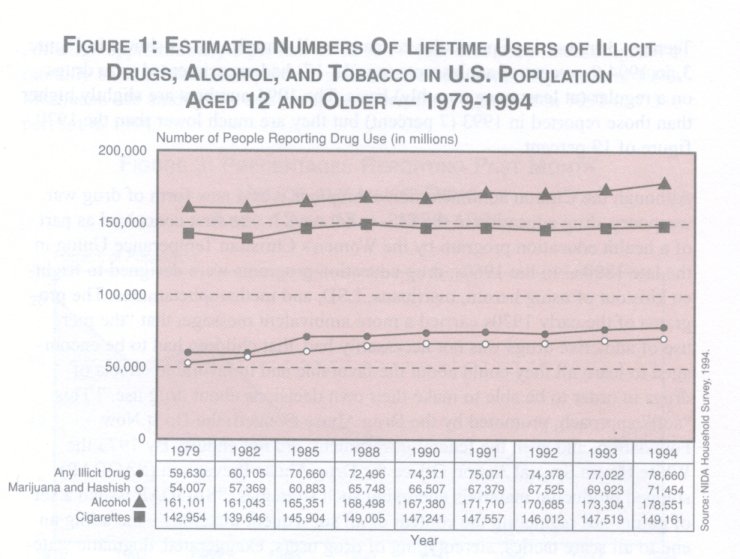

Figure 1:

Estimated Numbers of Lifetime Users of Illicit Drugs, Alcohol, and Tobacco in

U.S. Population - Aged 12 and Older - 1979-1994

Figure 2: Estimated Numbers of Lifetime Users

of Illicit Drugs, Alcohol, and Tobacco in U.S. Population in the Past 30 Days -

Aged 12 and Older- 1979-1994

Figure 3: Percentages Reporting Past Month Use

of any Illicit Drug - Aged 12 to 17 - 1979-1994

At the time of this publication, the federal government announced that drug use among teenagers has doubled since 1992. Not unexpectedly, both political parties seized upon the news to bolster their political ambitions and to declare once again a "new war on drugs." Lost in the debate were the facts that since the survey began, drug use has declined substantially among all youth, that illicit drug use among our youth for harder drugs (cocaine, heroin, and amphetamines) is extremely rare, and that the major drugs being used by our youth are tobacco and alcohol. Regardless of these data, one must always be concerned with all forms of drug abuse among our children and how best to prevent it. This monograph by Dr. Marsha Rosenbaum re-examines some of our assumptions regarding the best way to educate our youth on the dangers of drugs. Her article argues for a more factual approach for educating our youth rather than scare tactics that seem to be ineffective. A number of promising prevention models are presented that may well serve to help reduce the level of harm caused by all forms of drugs.

We welcome any thoughts you have on this important issue.

James Austin, Ph.D.

Executive Vice President

On April 29, 1996, Bill Clinton did what all presidents must do in the approach of an election year. He announced a "new" war on drugs, designed to encourage abstinence. Among Clinton's weapons in his arsenal is education as the means to eradicate drug use among teenagers. The hope is that if initial involvement with drugs can be prevented, a drug-free America may someday be a reality.'

Given the widespread use of drugs in the U.S., the goal of complete abstinence may be unrealistic. According to the most current household survey by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), approximately 79 million Americans have used illegal drugs, primarily marijuana, at least once in their lifetime (Figure 1). This number has increased steadily since the survey began in 1979 when the estimated number was 59.6 million. Less than 20 percent of these experimenters (approximately 12.5 million Americans) used illegal drugs regularly, or each month (Figure 2). The number of regular users has declined sharply since 1979 with the largest reductions occurring for the category of marijuana and hashish. In other words, whereas nearly one-third of Americans have tried illegal drugs, less than 5 percent of the population uses them regularly. And, alcohol and cigarettes remain the most dominant form of legal drug use.

Teenage drug use is of particular concern to all Americans. As shown in Figure 3, in 1994 9 percent of adolescents (age 12-17) had experimented with drugs on a regular (at least once monthly) basis. The 1994 numbers are slightly higher than those reported in 1993 (7 percent) but they are much lower than the 1979 figure of 19 percent.

Although the Clinton administration champions it as a new form of drug war weaponry, drug education in the U.S. is not new. It was first conceived as part of a health education program by the Women's Christian Temperance Union in the late 1800 S.2 In the 1960s, drug education programs were designed to frighten kids out of using heroin, marijuana, LSD, and methamphetamines. The programs of the early 1970s carried a more ambivalent message, that "the mere use of addictive drugs was not necessarily bad, that children had to be encouraged to learn all they could about the favorable and unfavorable effects of drugs in order to be able to make their own decisions about drug use."' This "soft" approach, promoted by the Drug Abuse Council, the Do It Now Foundation, and even the federal government, did not endure. By 1973 the White House Special Action Office for Drug Abuse Prevention (SAODAP) stopped producing materials endorsing such strategies. "SAODAP issued a set of guidelines regulating the content of all subsequent materials-including an end to all scare tactics, stereotyping of drug users, exaggerated, dogmatic statements, and demonstrations of the proper use of drugs."'

During the late 1970s and early 1980s, drug education programs proliferated with the explicit goal of "primary prevention." By 1983 any materials that did not endorse abstinence were censored from the drug education curriculum. For example, perhaps the most thorough and informative book for teenagers, Chocolate to Morphine: Understanding Mind-Active Drugs, by Dr. Andrew Weil and Winifred Rosen, was hastily removed from drug education curricula shortly after its 1983 publication because it stressed the importance of nonabusive relationships with drugs rather than total abstinence! Nonetheless, drug education programs were defined as more sophisticated than the old scare tactics, giving children information about the dangers of drugs as well as concrete psycho-social techniques for countering "peer pressure." Former First Lady Nancy Reagan instructed inner city children on how to "just say no." Drug education programs were also designed to instill self-esteem and self-control in school-children so they could fight the lure of drugs. Unfortunately, drug education does not seem to have successfully achieved its goal of abstinence among teenagers. In the years directly following the scare tactics and resistance campaigns, studies indicated an increase in drug-use among the targeted population.6 By the 1990s, following the "just say no" campaign of the 1980s, the use of marijuana and psychedelic drugs has increased among teens.7

Although approximately 8 percent of 12 to 17-year-olds used illicit drugs on a monthly basis in 1994, this percentage has increased from 6.6 percent in 1993. Marijuana use among this age group has risen from 4 percent in 1992 to 7.3 percent in 1994.9

As a sociologist and the mother of two teenagers, I am concerned about drug use as well as drug education. Based on the experience of my own children, 1 have begun to question the methods by which children are taught about drugs. T want to know why drug education has not achieved its goals, despite an outpouring of millions of dollars into this effort. My children have been given the standard "dose" of drug education through school and the media, but seem as ill-informed as I was at their age. Like most parents, I wish "the drug thing" would magically disappear and my children would simply abstain from using all intoxicating substances. I know this wish to be a fantasy. I can hope, however, that my children will not fall into the trap of a heroin addict I interviewed nearly twenty years ago. She, like myself at the time, was a "nice Jewish girl" who came from a middle class suburb in a large metropolitan area. Genuinely intrigued by her situation, I asked how she had ended up in jail and addicted to heroin. I will never forget what she told me, "When I was in high school they had these so-called drug education classes. They told us if we used heroin we would become addicted. They told us if we used marijuana we would become addicted. Well, we all tried marijuana and found we did not become addicted, so we figured the entire message was b.s. I then tried heroin, got strung out, and here I am."

We must begin to think critically about drug education in the U.S. This pamphlet begins by investigating the weaknesses of our most recent drug education programs. We then turn to an alternative approach to drug education: harm reduction. Finally, the most promising actual programs, both in the U.S. and abroad, are presented as models.

Drug education in the U.S. begins with young children, often starting as early as the third grade or approximately age eight. First, a particular program is usu ally adopted by a school and then the school's own teachers or outside "experts" teach the program's curriculum. No set content exists for such pro grams and these classes are sometimes couched in courses such as "family life," or "health education." In order to insure continued funding, drug education programs must produce "effective results." An objective review of the research findings to date, however, clearly demonstrates that most prevention programs have never been evaluated or have been evaluated using flawed research methods. In short, we do not know what works. As Mathea Falco reports, "Many schools rely on programs which have not been evaluated or, worse yet, have been found to have no impact. In 1988, a review of 350 differ ent school programs found that only 33 had any valid evaluation data, while just three programs reported reductions in tobacco, alcohol, or drug use. "° Proponents and opponents agree, however, that drug education programs are difficult to evaluate because test results are not always a valid indicator of fail ure or success." For instance, older children often do not take the programs seriously and may sabotage the testing process." Others simply regurgitate course content without sincere attitude or behavioral commitment. '3 Further, many programs claiming effectiveness use weak pre-test and post-test evaluation designs. These evaluations consist of administering a questionnaire to students to assess their attitudes and behaviors relative to whatever drug(s) are the focus of the particular program. The students' responses represent their attitudes toward drug use and actual drug use in the 6-12 months prior to the program. After the youth have completed the program, they receive a post-test questionnaire containing the same items as the pre-test questionnaire. If there are any differences between the pre-test and post-test results, program staff will interpret this as evidence that the program has had a positive effect.

The problem with such an evaluation is that there is no control or comparison group in the drug prevention program. Consequently, differences between the pre-test and post-test scores may be the result of a number of factors that are unrelated to program participation. Researchers refer to these as "confounding" factors. For example, improvements in the scores may be the result of the Hawthorne effect, or knowing that one "should" do better after completing the program. The student may alternately be exposed to factors completely unrelated to the drug education course, causing a change in attitudes and behavior. Studies show that while drug education programs may influence attitudes toward drugs, these programs produce little behavioral change. High school children, in particular, may state reasons for avoiding drugs, yet use them anyway." Some argue that although there are sometimes post-program increases in drug use as children age, onset is later and the numbers of users is fewer." Other researchers insist that the programs are too short, and once the lessons stop, their effects cease." They also maintain that any program without "environmental consistency" will fail:

It cannot be assumed that increased levels of perceived risks or personal susceptibility concerning specific drug-related behavior will automatically translate into behavioral changes. The experiences students have as they interact with their environment will potentially either positively or negatively reinforce their attempts to deal with the environmental pressures related to drug use. Attempts are likely to be supported if they are reinforced by peer reactions, social approval, availability of satisfactory alternative activities or other environmental reinforcers. Attempts to change behavior that are met with peer rejection, lack of participation in enjoyable activities, or other negative environmental reinforcers are not likely to be sustained over time.17

One of the most popular and prevalent school-based drug education programs is DARE (Drug Abuse Resistance Education). Since 1990, DARE has received over $8 million in direct federal funding plus millions more in state and local funds. Approximately 20,000 police officers have delivered drug education to an estimated 25 million youth as part of the DARE program. Evaluation after evaluation has shown "no long term effects resulting from DARE exposure."" A five-year study tracking DARE students and published in 1994 has shown that "quantitative and qualitative data both point in the direction of no longterm effects for the program in preventing or reducing adolescent drug use."" A study funded by the National Institute of Justice (which the agency later attempted to suppress), found the following:

DARE'S limited influence on adolescent drug use behavior contrasts with the program's popularity and prevalence. An important implication is that DARE could be taking the place of other, more beneficial drug use curricula that adolescents could be receiving. At the same time, expectations concerning the effectiveness of any school-based curriculum, including DARE, in changing adolescent drug use behavior should not be overstated. 20

Finally, targeting "at risk" populations for drug education may be ineffective at best. Anti-drug programs do not address deeper sociological risk factors of poverty, joblessness, lack of adequate housing and education.21 In addition, the definition of some children as "at risk" may ultimately be harmful by resulting in labeling and exclusionary policies.22

What's Wrong with Drug Education?

Drug education in the U.S. is based on several questionable assumptions about adolescence and drug use: 1) total abstinence is a realistic goal; 2) the use of illegal substances necessarily means abuse; 3) one form of drug use inevitably leads to other, more harmful forms; 4) understanding the risks inherent in drug use will deter children from experimentation; and 5) children are incapable of making responsible decisions about an issue as serious as drug use. Contemporary drug education programs have as their underlying premise the futile goal of abstinence from all illegal drugs. The expectation that adolescents will not experiment with altered states of consciousness is unreal at best.23, 24 Championing abstinence has thus lead to the inevitable failure of programs that have made this their primary goal because some form of drug use is nearly universal, and certainly integral to American culture .25 Thus, drug education programs, by virtue of their most basic assumption, are doomed to fail. As Erich Goode says:

Almost all drug education programs strive for prevention as their ultimate goal. It is possible that this goal is unrealistic with current experimenters and users. Perhaps moderate or wise use is a more realistic goal."

Another assumption pervading drug education is that use is equal to abuse. Some programs use the terms interchangeably while others utilize an exaggerated definition of use that results in defining anything other than one-time experimentation as abuse. A problem with the blurring of distinctions between use and abuse is the inconsistency with students' observations or experiences. When young people are told that once-a-month use of a substance is abuse, they often snicker. They see others, and often themselves, as people who have used an illegal substance without any of the addictive or deleterious effects that would constitute "abuse." No consensus exist as to which behaviors constitute drug use or drug abuse. Programs that do not differentiate between these two are therefore ineffective." ,"

A theory inherent in drug education is the "gateway" or "stepping stone" hypothesis. This theory argues that alcohol and cigarettes are "stepping stones" to illegal drugs, and the "softer" illegal drugs such as marijuana are the gateway to "harder" drugs such as cocaine and heroin.29 There is no evidence, however, that the use of one drug leads to another, and several studies have found that the vast majority of students who try drugs do not become abusers.30 Another premise of drug education is that if children simply understood the dangers of drug experimentation they would abstain." In the effort to encourage abstinence, "risk" and "danger" messages are often exaggerated. Aside from glaring falsehoods and ridiculous analogies (e.g., the fried egg commercial) these messages are often inconsistent with children's actual observations and experiences. In spite of what they may have heard, marijuana use did not make them seek out cocaine or heroin, Ecstasy did not melt their spine. According to Moore and Saunders:

Young people dutifully attend these classes and are then re-subjected to a world where drug taking is the norm rather than the exception. They see and experience the costs and benefits of drug use. Stories of the terrible side effects of drugs ring hollow alongside their own and others' experience of drugs."

The typical response of children to such contradictory information is to simply discredit the message as in the case of the heroin addict I interviewed in the 1970s.

Finally, most programs are predicated on the notion that teenagers are incapable of making decisions about drug use. Students are given the inconsistent message that although they must resist peer pressure and make their own decisions about drug use, they must always say "no." A common complaint about the DARE program, according to Wysong, Aniskiewicz and Wright, was from students who did not believe their opinions were taken into account:

It's like nobody cares what we think ... The DARE cops just wanted us to do what they told us and our teachers never talked about DARE ... It seems like a lot of adults and teachers can't bring themselves down to talk to students ... so you don't care what they think either.33

Aside from being intelligent, critical thinkers, teenagers sometimes have experienced drug use, before, during and after having received drug education. They often use their own experience and intelligence to decide whether or not to use drugs. In fact, most decide on their own to refrain. Studies conducted to discover the reasons why teenagers quit using marijuana found that health reasons, short term problems and negative drug effects, based on students own experience, motivated them. Thus, any form of drug education should interact with and respect both their ability to reason and their own experiences.34

A Harm Reduction Approach to Drug Education

Despite billions of dollars in drug prevention efforts, a sizable number of Americans continue to use drugs. Adolescent experimentation with drugs con tinues as well. Though we cannot eliminate drug use altogether, we can at least try to minimize its dangers. The best we can hope for, in lieu of total absti nence, is responsible use based on informed decisions. We must approach drugs in the same way we approach other potentially dangerous substances and activi ties. For instance, instead of banning the automobile, which kills far more teenagers than do drugs, we enforce traffic laws, prohibit driving while intoxi cated, and insist that drivers wear seat belts. We then likewise teach young adults how to use alcohol responsibly with messages like "know when to say when." We put warning labels on pharmaceutical drugs.

The basic assumptions and goals underlying this type of drug education program are designed to result in harm reduction. Watson defines this new approach as:

the philosophical and practical development of strategies so that the outcomes of drug use are as safe as is situationally possible. It involves the provision of factual information, resources, education, skills and the development of attitude change, in order that the consequences of drug use for the users, the community and the culture have minimal negative impact (p.14).3 5

Basic Assumptions

A harm reduction drug education program has four basic assumptions. First, "drugs" must be categorized broadly to include all intoxicating substances, including those which are legal. The fact that one drug or another is legal or illegal has very little to do with its inherent dangers, and a cursory look at the history of drug policy in the United States reveals that the placement of a substance in either a legal or illegal category is political rather than purely pharmacological. For example, marijuana smoking has not been proven to cause a single death, while tobacco smoking has been the cause of millions of deaths. The fact that marijuana is illegal and tobacco is not is obviously political. The National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws, however, is nowhere as powerful as the tobacco industry, and therefore cannabis remains illegal while cigarettes are widely available.

Another example is the drug MDMA, which lowers users' defenses without loss of control, enabling them to communicate more effectively in both therapeutic and non-therapeutic settings. MDMA or "Ecstasy," currently cannot be used for any purpose in this country even though before it became illegal in 1985 many licensed therapists reported remarkable psychotherapeutic results." Another drug used by psychotherapists, Prozac is an anti-depressant that enables chronically depressed individuals to function at normal levels. Therapists report initial positive results but diminishing returns and side effects with long term use. Nonetheless, Prozac, because it is manufactured by a large and powerful pharmaceutical house is fully legal, and prescribed to hundreds of thousands of users.

Children have a knack for seeing through inconsistencies and unfair practices, and are far less concerned with the legality of activities than are adults, who understand the implications of breaking the law. It is not enough to tell students they must refrain from certain drugs because they are illicit. Children often do not care and are sometimes attracted to drugs because they are illegal. Children will, however, use or reject a given substance for reasons having to do with its effects, availability, reputation, etc.

An effective drug education program must acknowledge legal status as a risk factor in itself because becoming involved with the criminal justice system has devastating implications beyond the physical effects of drug use. Teachers must then go on to discuss drugs as substances that affect the mind and body, without using legality as a way to distinguish between acceptable and unacceptable drugs. In a drug education curriculum it is imperative to categorize drugs in the broadest way possible, casting off distinctions between legal and illegal drugs in order to educate children about the nature of all psychoactive substances, including alcohol, caffeine, over-the-counter substances, and prescription drugs. A second basic assumption of a harm reduction drug education program is that total abstinence is not realistic. Drugs have always been and are likely to remain a part of American culture. We routinely alter our states of consciousness through accepted means such as alcohol, tobacco, caffeine, and prescription medications. Americans are perpetually bombarded with messages that encourage them to medicate with a variety of substances. In this context, and often acknowledging that legal-illegal distinctions are irrelevant to many adolescents, experimentation with mind-altering substances is "normal."37 Since total abstinence is not a realistic goal, we must take a pragmatic rather than moralistic view toward drug use. Like sexual activity, drug use will happen, so instead of becoming morally indignant and punitive, we should assume the existence of drug use and seek to minimize its negative effects.

A third assumption is that it is possible to use drugs in a controlled responsible way, and the use of mind-altering substances does not necessarily constitute abuse. The majority of drug use (with the exception of nicotine, which is the most addictive of all substances) does not lead to addiction or abuse. Instead, 80-90 percent of users control their use of psychoactive substances.38 We quote from Goode:

The truth is, as measured by harm to the user, most illicit drug users, like most drinkers of alcohol, use their drug or drug of choice wisely, nonabusively, in moderation; with most, use does not escalate to abuse or compulsive use.3 9

As a consequence of its illegal status, responsible drug use is often hidden. Those with a "stake in conventional life" have the most to lose from exposure." They control their use of substances, legal and illegal, to insure their status as conventional people. It is a mistake to assume that because responsible users of illegal drugs are not visible that they do not exist. Children could benefit from understanding how others achieve a moderate, responsible lifestyle in which drug use is present but made safe through a variety of conscious mechanisms. If, in the context of drug education, adolescents see and hear exclusively from abstainers or ex-addicts, how will they know how to function in the middle?

A fourth assumption of a harm reduction drug education program in that perhaps nothing is more crucial regarding safe drug use than context. In his seminal work, Drug, Set and Setting, Norman Zinberg imparts the notion of three essential elements which lay the groundwork for an understanding of drug use." First, the pharmacology of the drug itself is important, as well as the dosage level. Second, the "set," or psychological state, of the user at the time of use must be understood. Finally, the setting, including geography, social group and even weather affects one's experience of a particular drug. These three elements form the context of use, and make the differences between drug use and abuse, and it is within this context that educational efforts must be placed.42

Goals of Drug Education

Although harm reduction approaches to drug use have not yet become institutionalized, they are not new. Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) and Students Against Drunk Driving (S'ADD), as well as many "designated driver" programs, have taken such an approach to alcohol use. Instead of attempting to prohibit alcohol use completely, these approaches have sought to minimize the dangers of driving while intoxicated. David Duncan used a similar approach to glue sniffing in the early 1970s, which resulted in an end to a series of deaths related to unsafe "huffing."43

In order to reduce drug-related harms, goals of drug education should first include facts about the physiological effects of drugs, as well as their risks and benefits. Drug education courses allow us the opportunity to teach children physiology. Programs should begin with an extensive look at how drugs affect the body.

There are many concrete risks and dangers in the use of psychoactive substances. We must, however, separate the real from the imagined dangers of drugs and impart this information within the appropriate context. Drugs can provide users with a number of benefits, and this simple but contradictory fact explains why drug use persists. The trick is to find a balance between cost and benefit. A useful drug education program will help students to strike a balance between real information and propaganda designed only to deter use. An explanation for the continued increase of marijuana use among teenagers, is their refusal to believe the exaggerated negative information that has been disseminated over the past decade.

We must incorporate children's experience, expertise and intelligence in a drug education curriculum. Children often know more than we credit them with about drugs through experience, family, and the media. They are also much more thoughtful, intelligent and concerned about their own well-being than adults may acknowledge. An effective drug education program will incorporate these observations.44 Both "peer education," where the students themselves direct the program, and "confluent education," where information is coupled with experience, are two such vehicles.45 In order to achieve the goal of incorporating children's experience and expertise, there must be no repercussions for their input and honesty.

Finally, positive role models must be incorporated into drug education. It has become common practice for individuals "in recovery," who have had prior abusive relationships with drugs, to teach children about the pitfalls of using drugs. These individuals, who have obviously failed to control their use seem unlikely models, and are comparable to obese people teaching classes on weight control. Yet, individuals who have no experience with such substances are equally as unlikely to capture the attention of students. Employees of drug treatment facilities as teachers have a conflict of interest, since their employers profit from a definition of drug abuse that is broad and requiring treatment.

Individuals with non-problematic experiences with drugs, who can act as positive role models, should educate children about drug use." These individuals should not endorse use but convey the methods they themselves use for avoiding abuse or accidents, e.g., keeping dosages at moderate levels, pacing, not driving while intoxicated, and never using drugs at work or school.

Parents who have experimented with drugs should talk to their children. However, in the past fifteen years, with DARE police suggesting criminal justice sanctions, even parents who used drugs moderately have become secretive. Instead of providing examples of responsible use, most hide and deny their use, withholding important practical information from their children and deceiving them. In addition, open and honest communication between parent and child has been curtailed.

I recently attended a series of "drug awareness" evenings at my 12-year-old's middle school. The course, taught by two employees of a local drug treatment program, utilized a number of factually erroneous scare tactics to dissuade children from experimentation. The program disappointed but did not surprise me. It did nothing to educate my child about the actual risks and how to minimize the effects of drug use. I would have preferred no drug education to the rhetoric that passes for information today.

There are a small number of programs in the United States and abroad that disseminate useful information about drugs to young people. These programs contain written as well as audio-visual materials and are taught in a classroomlike setting. Since these programs are viewed as unconventional due to their assumptions and goals about drug use and education, they have not been incorporated into school curricula. Some have continued to operate, nonetheless, and serve as examples in the structuring of new, innovative programs. Harm-Reduction Drug Education (HRDE)

Conceived by Julian Cohen, Ian Clements, and James Kay, Harm-Reduction Drug Education is a drug education approach used in the United Kingdom. Cohen says,

HRDE is secondary rather than primary prevention on the understanding that we cannot prevent drug use per se and that attempts to do so may be counterproductive. It is education about rather than against drugs ... It is non-judgmental and neither condones or condemns drug use but accepts that it does, and will continue to, occur. As such it is consumer education. A key aim is to develop an open and honest dialogue with young people. A key principle is that the right of young people to make their own decisions regarding drug use is respected."

The program's form varies according to group needs and local situation. Rather than "resisting peer pressure," HRDE's goal is to foster what it calls "positive peer support." For example, students learn techniques for performing lifesaving techniques in the event of an overdose or accident. With an emphasis on peer involvement in education, teachers take on the role of facilitator. Materials for the program consist of Taking Drugs Seriously, for ages 12 and older, and Don't Panic for professionals.48 There are eight main sections:

1. Facts about drugs-which gives accurate information and focuses on benefits as well as risks.

2. Personal drug use-in which risk-taking is examined in a non judgmental manner.

3. Attitudes-in which stereotypes are challenged.

4. Harm reduction-in which drug, set, and setting factors are highlighted.

5. The law and drugs-which looks at laws and rules, legal rights, and handling conflict.

6. Giving and receiving help-which focuses on the skills needed to help oneself and to help others.

7. Community action-which looks at responses to drug use both locally and nationally.

8. Parents and Community Workshop-to help educate parents and other adults.49

HRDE has had limited exposure in the United Kingdom. Advocates of traditional primary prevention, and who control funding, are reticent to use the program without preliminary results. Without exposure, however, it is impossible to gather information on the program. Still, HRDE has structured a practical program that incorporates the assumptions and goals underlying effective drug education.

Mothers Against Misuse and Abuse

Mothers Against Misuse and Abuse (MAMA) was founded in Oregon in 1982 by Sandee Burbank. According to longtime drug educator Mark Miller, its purpose is "to provide education and information on legal and illegal drugs." MAMA uses a "rational" approach by "providing current and scientific drug education and information to all ages of society; offering individual and familyoriented alternatives to drug use; creating critical lines of communication between law enforcement, educators, service providers, parents and youth; questioning the Madison Avenue techniques of advertising over-the-counter drugs, alcohol, nicotine and caffeine."50

MAMA currently utilizes pamphlets as written foundations for their programs. In the foreword to "How to Teach Your Children About Drugs," Mark Miller reveals his perspective:

I've often been asked if I could provide parents with a realistic, health-oriented means of teaching their children about drugs. These parents wanted an approach that accurately portrayed the world of drugs, with techniques that promoted responsible decision-making skills lacking in much of today's drug education. ...Many felt approaches such as "Just Say No" are simplistic, ineffective and confusing. Drugs are extensively advertised, openly consumed by adults and easily obtained in grocery stores ... This pamphlet provides information and guidelines to help parents and children make responsible decisions in a drug-filled worlds'

Other pamphlets include "Drugs and Seniors" and "Using Alcohol Responsibly." The program is based on a generic set of "Drug Consumer Safety Rules" that apply to prescription drugs, over-the-counter substances, tobacco, caffeine, alcohol, and illegal drugs. For each of these substances or class of substances the reader is encouraged to ask: 1) What is the name of the chemical?; 2) What part of may body does it effect?; 3) What is the correct dosage?; 4) What drug interactions will occur?; 5) What allergic reactions can occur?; 6) Will it produce tolerance?; 7) Will it produce dependence?

MAMAS program is not radical. It includes real information about both legal and illegal drugs. MAMA'S value lies in its comprehensive, non judgmental, yet cautionary perspective on drug education.

Drug education is vital to the prevention of drug abuse. Traditional approaches, however, because they are based on questionable assumptions about drug use in general and adolescent behavior, in particular, have not succeeded in achieving this goal.

A useful approach to drug education incorporates the tenets of a "harm reduction" perspective. For a variety of social, cultural and personal reasons, drug use (illegal or legal) will never be eliminated. Thus, we must assume the existence and use of psychoactive substances and focus our energies on reducing their harmful effects. As Duncan states, this approach may run contrary to that of traditional drug educators:

Many health educators will be uncomfortable with this direction. They may see it as a surrender in the war on drugs. Others will see it as a refocusing of our efforts on what really matters for health education-the prevention of health problems. It is the proper role of health educators to help people live healthier lives, not to act as moral police.52

Drug education should be based on realistic assumptions about drug use. Specific goals and programs should be tailored around these assumptions. We should not lose sight of the fact that human beings are complex, human behavior is always changing and teenagers are bright and critical. Programs must address the needs of individuals within their social context and be as flexible, open, and creative as the young people they must educate.

l . Mathea Falco, The Making of a Drug-Free America. New York: Times Books, 1992.

2. Patricia A. Winters, "Getting High: Components of Successful Drug Education Programs," Journal ofAlcohol and Drug Education, v. 35, n. 2, Winter, 1990.

3. Avram Goldstein, Addiction: From Biology to Drug Policy. New York: W .H. Freeman and Company, 1994, p. 207.

4. Erich Goode, Drugs in American Society. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc., 1993, p. 334. Goode also cites H.S. Resnick, It Starts With People: Experiences in DrugAbuse Prevention. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare, 1978.

5. Andrew Weil, M.D. and Winifred Rosen, Chocolate to Morphine: Understanding Mind-Active Drugs, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1983.

6. Lloyd D. Johnston, Patricia M. O'Malley and Jerald G. Bachman, "National Survey Results on Drug Use from Monitoring the Future Study, 1975-1992," U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, PHS, 1993.

7. In a report prepared for the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy by ABT Associates in Cambridge, researchers found marijuana use up in most areas of the country, and "Hallucinogens such as LSD, mescaline and PCP are re-emerging..." The San Francisco Chronicle, May 12, 1994, p. A12.

8. Preliminary Estimates from the 1994 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Advance Report Number 10, September 1995.

9. Ibid

10. Mathea Falco, The Making of a Drug-Free America. New York: Times Books, 1992.

11. William H. Bruvold, "A Meta-Analysis of the California School-Based Risk Reduction Program," Journal of Drug Education, v. 20, n. 2, 1990; Chwee Lye Ching, "The Goal of Abstinence: Implications for Drug Education," Journal o fDrug Education, v. 11, n. l, 1981.

12. Constance Lignell and Rugh Davidhizar, "Effect of Drug and Alcohol Education on Attitudes of High School Students," Journal ofAlcohol and Drug Education, v. 37, n. 1, Fall, 1991.

13. Chwee Lye Ching, "The Goal of Abstinence: Implications for Drug Education," Journal of Drug Education, v. 11, n. 1, 1981.

14. Sehwan Kim, Jonnie McLeod and Charles L. Palmgren, "The Impact of the `I'm Special' Program on Student Substance Abuse and Other Related Student Problem Behavior," Journal of Drug Education, v. 19, n. 1, 1989; William H. Bruvold, "A Meta-Analysis of the California School-Based Risk Reduction Program," Journal of Drug Education, v. 20, n. 2, 1990; Susan G. Forman, Jean Ann Linney and Michael J. Brondino, "Effects of Coping Skills Training on Adolescents at Risk for Substance Abuse," Psychology of Addictive Behavior, v. 4, n. 2, 1990; Michael D. Newcomb, Bridget Fahy and Rodney Skager, "Reasons to Avoid Drug Use Among Teenagers: Associations with Actual Drug Use and Implications for Prevention Among Different Demographic Groups," Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education, v. 36, n. 1, Fall, 19'90.

15. Mary Ann Pentz, James H. Dwyer, David E MacKinnon, et al,

"A Multicommunity Trial for Primary Prevention of Adolescent Drug Abuse: Effects on Drug Use Prevalence," JAMA, v. 261, n. 22. June 9, 1989. 16. Raymond Tricker and Lorraine G. Davis, "Implementing Drug Education in Schools: An Analysis of the Costs and Teacher Perceptions," Journal of School Health, v. 58, n. 5, May, 1988; Phyllis Ellickson, Robert M. Bell and Kimberly McGuigan, "Preventing Adolescent Drug Use: Long-Term Results of a Junior High Program," American Journal of Public Health,

v. 83, n. 6, June, 1993.

17. Brian R. Flay, Stacey Daniels and Calvin Cormack, "Effects of Program Implementation on Adolescent Drug Use Behavior," Evaluation Review, v. 14, n. 3, June, 1990, p. 448.

18. Earl Wysong, Richard Aniskiewicz and David Wright, "Truth and DARE: Tracking Drug Education to Graduation and as Symbolic Politics," Social Problems, v. 41, n. 3, August, 1994; Dennis Rosenbaum, Robert L. Flewelling, Susan L. Bailey, Chris L. Ringwalt, Deanna L. Wilkinson, "Cops in the Classroom: A Longitudinal Evaluation of Drug Abuse Resistance Education (DARE)," Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, Vol. 31, No. 1, February 1994, 3-34.

19. Earl Wysong, Richard Aniskiewicz and David Wright, "Truth and DARE: Tracking Drug Education to Graduation and as Symbolic Politics," Social Problems 41 (3), August 1994.

20. Susan T. Ennett, Nancy S. Tobler, Christopher L. Ringwalt, Robert Flewell ing, "How Effective is Drug Abuse Resistance Education? A MetaAnalysis of Project DARE Outcome Evaluations," American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 84, No. 9, September 1994, p. 1394-1401.

21. Peter Greenwood, "Substance Abuse Problems Among High-Risk Youth and Potential Interventions," Crime and Delinquency, Vol. 38, No. 4, October, 1992, pp. 444-458.

22. Joel Brown and Marian DAMMED Caston, "On Becoming `At Risk' Through Drug Education," Evaluation Review Vol 19, No. 4, August 1995, p. 451-492.

23. Andrew Weil, The Natural Mind, Boston, MA: Houghton-Mifflin Company, 1972; Joel Fort, The Addicted Society, New York: Grove Press, 1981.

24. "Drug Use Among Youth: No Simple Answers to Guide Prevention," GAO Report, December, 1993.

25. Chwee Lye Ching, "The Goal of Abstinence: Implications for Drug Education," Journal of Drug Education, v. 11, n. 1, 1981.

26. Erich Goode, Drugs in American Society. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc., 1993, p. 335.

27. David F. Duncan, "Problems Associated with Three Commonly Used Drugs: A Survey of Rural Secondary School Students," Psychology of Addictive Behavior, v. 5, n. 2, 1991, p. 93-96.

28. "Drug Use Among Youth: No Simple Answers to Guide Prevention," GAO Report, December, 1993.

29. Denise Kandel, "Stages in Adolescent Involvement in Drug Use," Science, v. 190, 1975, p. 912-914; Steve. G. Gabany, Portia Plummer, "The Marijuana Perception Inventory: The Effects of Substance Abuse Instruction," Journal of Drug Education v 20, n. 3, 1990, p. 235-245.

30. Brown, J.H. and Horowitz, J. E., "Deviance and deviants: Why adolescent substance use prevention programs do not work" Evaluation Review 17, 5, 1993, pp. 529-555; Lynn Zimmer and John Morgan, Exposing Marijuana Myths: A Review of the Scientific Evidence. New York: Open Society Institute, October ,1995, p.14.

31. Jerald G. Bachman, Lloyd D. Johnston, Patrick M. O'Malley, "Explaining the Recent Decline in Cocaine Use Among Young Adults: Further Evidence That Perceived Risks and Disapproval Lead to Reduced Drug Use," Journal of Health and Human Social Behavior, v. 31, n. 2, June, 1990, p. 173-184.

32. David Moore and Bill Saunders, "Youth Drug Use and the Prevention of Problems," International Journal on Drug Policy, vol. 2, n. 5, March-April, 1991, p. 3.

33. Earl Wysong, Richard Aniskiewicz and David Wright, "Truth and DARE: Tracking Drug Education to Graduation and as Symbolic Politics," Social Problems 41 (3), August 1994.

34. Chorsie E. Martin, David F. Duncan and Eileen M. Zunich, "Students Motives for Discontinuing Illicit Drug Taking," Health Values: Achieving High Level Wellness, v. 7, n. 5, September-October, 1983, p. 8-11.

35. Watson, M., "Harm Reduction: Why do It?" International Journal of Drug Policy 5, 13-15, 1991.

36. Beck, J. And Rosenbaum, M., Pursuit of Ecstasy: The MDMA Experience. New York: SUNY Press, 1994.

37. M. Newcomb and P Bentler, "Consequences of Adolescent Drug Use: Impact on the Lives of Young Adults," Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1988; J. Shedler and J. Block, Adolescent Drug Use and Psychological Health: A Longitudinal Inquiry, American Psychologist, v. 45, 1990, p. 612-630.

38. Thomas Nicholson, "The Primary Prevention of Illicit Drug Problems: An Argument for Decriminalization and Legalization," The Journal of Primary Prevention, v 12, n. 4, 1992; Charles Winick, "Social Behavior, Public Policy, and Nonharmful Drug Use," The Milbank Quarterly, v. 69, n. 3, 1991.

39. Erich Goode, Drugs in American Society. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc., 1993, p. 335.

40. Dan Waldorf, Craig Reinarman and Sheigla Murphy, Cocaine Changes. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1991; Jerome Beck and Marsha Rosenbaum, Pursuit of Ecstasy: The MDMA Experience. New York: SUNY Press, 1994.

41. Norman Zinberg, Drug, Set, and Setting. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984.

42. For an interesting discussion of the role of context in cross cultural settings, see Charles Grob and Marlene Dobkin de Rios, "Adolescent Drug Use in Cross-Cultural Perspective," The Journal of Drug Issues, v. 22, n. 1, 1992.

43. David Duncan, Thomas Nicholson, Patrick Clifford, Wesley Hawkins, and Rick Petosa, "Harm Reduction: An Emerging New Paradogm for Drug Education," Journal of Drug Education Vol. 24, No. 4, 1994, p.281-290.

44. Chorsie E. Martin, David E Duncan and Eileen M. Zunich, "Students Motives for Discontinuing Illicit Drug Taking," Health Values: Achieving High Level Wellness, v. 7, n. 5, September-October, 1983, p. 8-11.

45. For an excellent discussion of peer education see Julian Cohen, "Achieving a Reduction in Drug-related Harm through Education," in Nick Heather, Alex Wodak, Ethan A. Nadelmann and Pat O'Hare, eds., Psychoactive Drugs and Harm Reduction: From Faith to Science. London: Whurr, 1993; and for confluent education see Joel H. Brown and Jordan E. Horowitz, "Deviance and Deviants: Why Adolescent Substance Use Prevention Programs Do Not Work," Evaluation Review, v. 17, n. 5, October, 1993,

p. 529-555.

46. Zigmund A. Kozicki, "Why Do Adolescents Use Substances (Drugs/Alcohol)?" Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education, v. 32, n. l, Fall, 1986.

47. Julian Cohen, "Achieving a Reduction in Drug-Related Harm through Education," in Nick Heather, Alex Wodak, Ethan A. Nadelmann and Pat O'Hare, eds., Psychoactive Drugs and Harm Reduction: From Faith to Science, 1993, p. 69.

48. I. Clements, J. Cohen and J. Kay, Taking Drugs Seriously: A Manual of Harm Reduction Education on Drugs. Liverpool: Healthwise, 1991; Cohen, J. and Kay, J., Don't Panic: Responding to Incidents of Young People's Drug Use. Liverpool: Healthwise.

49. Julian Cohen, "Achieving a Reduction in Drug-Related Harm through Education," in Nick Heather, Alex Wodak, Ethan A. Nadelmann and Pat O'Hare, eds., Psychoactive Drugs and Harm Reduction: From Faith to Science, 1993, p. 71.

50. Mothers Against Misuse and Abuse, "Using Alcohol Responsibly," Mosier, Oregon: MAMA.

51. Sandee Burbank and Mark Miller, "How to Teach Your Children About Drugs," Hosier, Oregon: MAMA, p. 1.

52. David E Duncan, "A New Direction for Drug EducationHarm Reduction," The Catalyst Vol. 22, No. 2, Fall 1995, p. 8-9.