| - |

Drug Abuse

INEBRIANTIA

ALCOHOL

Remarks on Acute Intoxication

Acute and chronic alcoholism are as old as alcoholic beverages themselves. Their explanation must be sought in the particular properties of these liquors and in the dispositions of mankind.

Every person, man, woman, and child, savage native of a distant island or inhabitant of a civilized country, knows what acute intoxication is like. It is described with all its distressing consequences in the world's oldest chronicle, the Bible. Artists have depicted it according to their diverse conceptions in representations of the altered activity of the brain reflected in the physiognomy and the behaviour of the drunkard. Poets and authors have described to the world the effect of alcohol in verse and prose, approvingly and disapprovingly according to their point of view. Humour, irony, and earnest reflection are contained in these works which exhibit pure unbiased reality or are devoted to the exposition from amoral or ethical point of view of the consequences of alcohol abuse. There is a Greek inscription on a tomb more than two thousand years old which a poet composed in the form of an epitaph on the defunct who succumbed to the combined action of alcohol and cold during acute alcoholism.

Evpomatog Tot deviip TO 3' &germ:000(ov

XvilEptag iteevcov ,ur75apec VVICTOc rots.

Kai yap eyth TOlOVTOV r &goy. avri roAnog

IlarpiSog 60velav Kripat e0Eppaitevoc

Wanderer, hear the warning of Orthon of Syracuse.

Never travel at night and in winter when drunk!

For such, you see, was my unhappy destiny; not at home,

But here I lie, covered with alien soil.

Why is it that alcohol has been and is still the subject of such diversity of opinion? The reason must be sought in the exceptional position which it occupies among the stimulating and narcotic substances, both as a producer of intense or light forms of inebriation and in respect to the effects which are called forth if it is used habitually in large quantities. In addition to this we must mention the ease with which it can be procured, its universal application, and, what is of supreme importance, the numerous possibilities of obtaining it from vegetable substances which in a suitable form are distributed over the whole world. On this earth there has been more than one Noah to make use of grapes in the production of an alcoholic beverage, wine, and to teach others the method. Many others drew their conclusions from accidental observations and became inventors of other fermented liquors.

There was probably never a time or a country in the world where alcoholic beverages were not used on special occasions or even habitually with the same aim and in most cases with the same result, viz. to tear the soul away from everyday life and direct it into another sphere where it is not confined within the walls of plain and customary monotony, or burdened with disagreeable and sad impressions, but on the contrary attains gaiety, temporary happiness, and even forgetfulness. This has always impelled man to the use of alcoholic beverages which are indeed highly suited to produce this result, provided that they reach a fit organism in favourable doses.

This was not only always the case, but it will be so in future as long as man and liquor are on this earth. And if in thousands of years some cosmic catastrophe establishes a new order of things, the new man of the future will once more learn to prepare and delight in alcoholic beverages. He also will undergo the same experience with this intoxicant which countless generations have had before him. He will learn that the desired effects may be accompanied by others of a disagreeable nature which are unpleasant in the experience and objectively repugnant. For this reason the helots were forced to become drunk and in this state were led into the dining-halls to show the young Spartans how debasing drunkenness is.

The disagreeable secondary effects are produced according to the same laws which govern the effects of every medicine or toxin. They are nevertheless influenced in their form by individual factors. At all times, for instance, there have been men who after a fit of alcoholic excess were affected with vomiting, as is shown in an ancient picture of 1,500 years before our era', i.e. dating from the new Egyptian empire, which represents a woman in the act of vomiting. They also experienced troubles of the motor organs, mental disorders, loss of consciousness, and other grave effects. The consequences of an occasional excess, which is nothing else but an acute intoxication, influence the organism for a relatively sort period of time if no specially aggravating circumstances are present. However, they excite our aversion, because they reveal to us the fact that the individual has, voluntarily or involuntarily, infringed the laws of society.

The force of the reactions with respect to the apparent obnoxiousness has at all times depended on the sensitiveness of the observer. This latter has extremely wide limits, from the most tolerant indulgence to the most severe condemnation. It is just this different estimation which explains the various verdicts arrived at when the intoxicated person has committed an act against the law. Medical men must judge the mental state of the offender at the moment of his culpable act as in every other case where doubts arise as to the free will of the delinquent. On the other hand, if no infringement of the law takes place, and only an alcoholic excess is present, then, in my view this is a purely private concern of the individual. It is the business of other persons just as little as the voluntary state of cocainism or morphinism, or the state of caffeine inebriety produced by drinking large quantities of strong coffee, or excessive gambling, etc. Everybody has the right to do himself harm, and under normal circumstances this right may not be taken from him so long as he is not liable to military service. To some extent acute alcoholic intoxication, although easily mended, nevertheless causes damage to the organism. In this way it was frequently regarded in ancient times, and Plato is to a certain degree right when he makes Eryximachos say in the Symposium: "It seems to me indeed quite clear that inebriety is very injurious to man." Here we must take into consideration chronic alcoholism, the state of drunkenness.

Chronic Alcoholism

By chronic alcoholism I understand the state of a person who is led by a strong inclination or craving to taking daily or at regular intervals a dose, which may be very large, of a concentrated alcoholic beverage, so that it gives rise in him to functional disorder of the brain, of which he is himself conscious and which others perceive, and finally to organic modifications. This acquired state corresponds to our conception of inebriation, and a person in this state is an alcoholic. If we transfer this definition to real life, it will be seen that it is applicable to some only of those individuals who take alcohol. Drunkards are sick and therefore unhappy persons. They are also a calamity for their country if they are numerous, particularly because drunkenness renders impossible that regular work upon which a country's prosperity is founded.

The alcoholic is unhappy because he is usually aware that he is a prisoner in the iron embrace of his passion. The action of alcohol diminishes or annihilates will-power. From this point of view, and here only, does alcohol resemble morphia. Essentially there are great differences between the two substances and the impulses to which they give rise. The craving for alcohol is not so violent as that for morphia. No racking pains of the nerves, no state of extreme misery occurs such as takes place after the action of morphia on the brain has ceased. Consequently there is no necessity to supply the brian with a new dose. No internal constraint compels the drinker, like the morphinist, to increase the doses administered. When a cure is undertaken in a clinic I have frequently observed that the former does not suffer so much as the latter. It has not been proved with certainty whether or not a withdrawal cure causes delirium.

• Even animals may have the taste for alcoholic beverages to such a

degree that when the opportunity arises they make use of them with a certain display of intelligence. The horse of a wine merchant was discovered lying in the cellar amidst a heap of broken bottles, striking with its hoofs against the wine barrels. On being lifted up it fell down again. It was completely drunk. For some time its master had noticed that the horse had attacks of vertigo and fell frequently. The animal had been fed to strengthen it after overwork with oats soaked in wine. A lazy servant, instead of mixing the oats with wine, had administered

the latter from the bottle. One night the intelligent animal had got loose, opened the latch of the cellar with its teeth, ravaged among the wine and devastated the cellar.

During my experiments I saw a hedgehog which had been presented with a saucer of warm, very sweet brandy drink it at intervals without leaving a drop. Some hours later, exactly as in the case of a human being who had taken too much, the typical symptoms of "seediness" set in.

Alcoholism and Heredity

Alcoholism is a calamity for mankind in yet another respect. Not only does the individual, who is of comparatively little consequence to the activity of the universe, suffer, but his descendants engendered during the state of drunkenness may also be degenerate. This will be understood in respect to alcohol better than in the case of other poisons which intoxicate the organism habitually or ex professo. All bodies endowed with poisonous forces with the opportunity to act under these circumstances may influence the spermatozoa or ova and exercise a chemically noxious effect on their functions. The scientific mechanism of the phenomenon is well known as regards alcohol. It belongs to the group of substances which, like chloroform, ether, benzene, carbon sulphide, etc., are capable of dissolving the fatty matter (lecithin, etc.) contained in the organic complex. The possibility of such action is also present in the case of the sperma and the ovum. Both of them may be deteriorated in their functions. That is to say the acute chemical modification to which they are subjected may leave an impression which, transferred to the living being to which they give birth, communicates a morbid disposition, generally in the form of disorders of the nervous system. The known forms of alcohol in all the organic troubles which they evoke act in the same way, but with different degrees of energy.

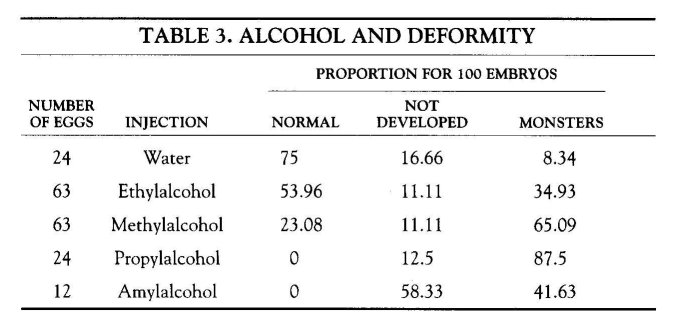

This can be proved experimentally in fertilized eggs. If different alcohols are injected in an appropriate manner into the interior, conclusions may be drawn as to the relative toxicity of the various alcohols by observing the greater or smaller number of eggs which are hatched and produce normal chickens, the number which are not hatched at all, and the number of those which give rise to freaks (see Table 3).

There are three kinds of defects due to alcohol which are liable to appear in the offspring:

(1) The inclination to alcohol.

(2) Mental diseases.

(3) Criminality.

Numerous experiences prove that this is the case. They also prove that alcoholic degeneration may spare the members of the first or second generation, or at least that it does not become apparent among them. With respect to the first and second class of the degenerative influences of alcohol the following table, founded on positive observations, shows clearly alcoholic deterioration.

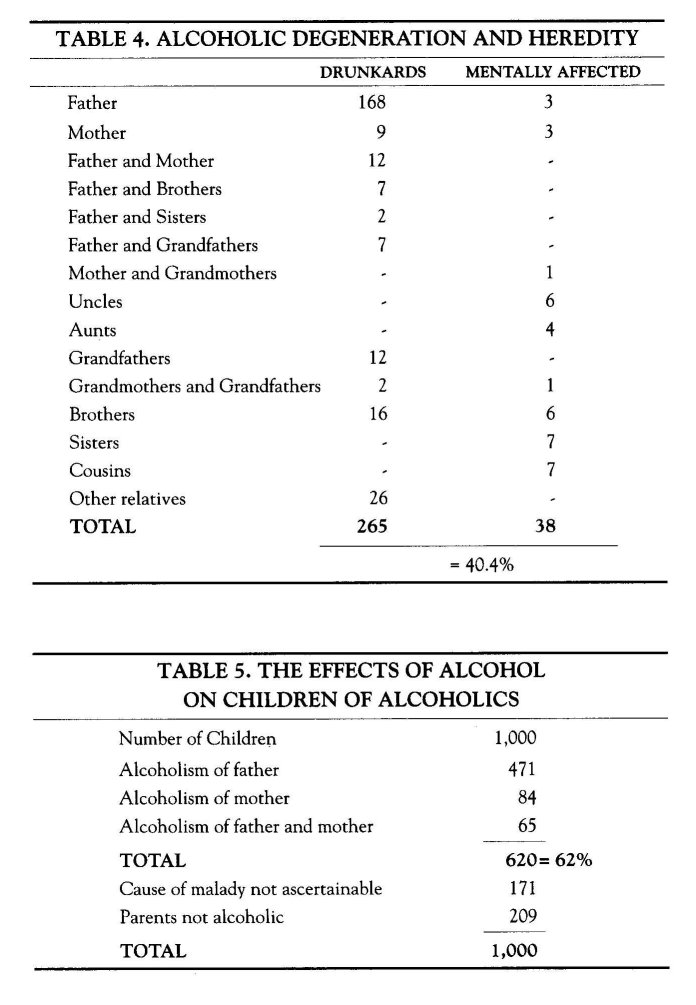

Of 600 drunkards, the parents and nearest relations were alcoholic or affected with mental diseases in the proportions shown in Table 4.

Other inquiries made at the Bicetre Hospital in Paris as to the influence of alcohol on the production of degenerate, idiotic, epileptic, and mentally and morally enfeebled children show the sinister role which alcoholism plays in this connection. Table 5 shows the results obtained in an inquiry into the parentage of 1,000 such abnormal children.

The influence of parental alcoholism on the criminal propensities of the offspring has been proved in the case of a family very interesting from a toxicological point of view.

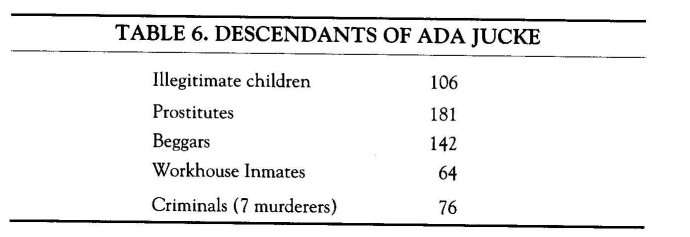

Ada Jucke, born in 1740, lived till after 1800. She was a drunkard, a thief, and a vagabond. In 1874 six of her descendants were in prison. Eight hundred and thirty-four persons were identified as her direct descendants, and the conditions of living were ascertained with accuracy in the case of 709 of these (see Table 6).

The criminals spent 116 years in prison and for 734 years they were sustained by public charity. In the fifth generation nearly all the women were prostitutes and the men criminals.

The primary cause of the injuries to which the brain is subjected is that the alcohol reaches the latter and is retained for some time on account of the frequently renewed application of the drug. At the beginning of the last century, for instance, in the cerebral cavities of a drunkard who was dissected immediately after death, a clear liquid was found which tasted and smelt of gin. The amount of alcohol concealed in the brain after alcoholic excesses has frequently been ascertained in our own days. In one of these individuals 3.4 c.c. of alcohol were found, and in another 1.04 cc. In a third with 720 gr. of brain 3.06 c.c. were ascertained. To my own knowledge the higher alcohols, especially amylic alcohol and the oils combined therewith, attach themselves for a longer period and more powerfully to the brain.

Alcohol gives rise to the preceding symptoms of a general kind. If we turn to particular cases it will be seen that the effects directly or indirectly called forth by the abuse of alcohol are so numerous that few poisons are capable of evoking them in such variety. Only those which react, like carbon monoxide, carbon sulphide, lead, etc., and are endowed with powerful chemical energy can be compared to it in this respect. Primary disorders which pass into the nervous system and into important organs combine with secondary disturbances which depend on the former and follow their own course after they have been initiated.

This is not the place to study in detail the organic troubles caused by alcoholism. They can easily be followed from the general outlines I have given above. Many volumes might be filled with descriptions of the symptoms of alcoholism. They would commence with scenes out of the Bible, and the experience of several thousand years would follow. From whatever epoch these descriptions are taken they will always be similar to each other and will always remain true.

Thence the pale complexion, the trembling of the nerves of the wine-soaked body . . . the bloatedness of the skin ... the insensibility and numbness of the nerves, or on the other hand the twitching of the whole body. What shall I say of the inclination of these people to faintness? What of their disorders of seeing and hearing?

These were the words of a Roman nineteen hundred years ago. After the lapse of an equally long period it will still be true thdt there is hardly an organ or an organic function which is not disturbed in some way or other in episodic, relapsing, impulsive, and habitual drunkards. It is not possible to predict which of these troubles will be produced in a particular case or how they will be produced. "Individual chance," as I may call it, creates extremely various phenomena. But the past also teaches us that the injurious consequences of alcohol will never cease and that man will rather submit to them than renounce it. At the beginning of the first century of our era Martial satirically depicted this in a poem which will always remain true and typical, and which may also be applied to other evils of the same kind.

Phryx, the worthy drinker, was blind

In one eye, and the other was running.

To him said Heras, the doctor: Avoid wine!

If you continue like this you will see nothing.

Phryx smilingly answered: Good-bye to thee, my eye! And on the spot he had many glasses mixed.

Do you want to know the end?

Phryx drank wine and his eye poison.

It seems unnecessary to describe in detail the moral consequences of alcohol in the drunkard. His behaviour towards himself when he is under the influence of alcohol and his conduct towards his family and society, even if he does not violate any laws, leaves much to be desired in respect to moral sense and duty. The higher qualities of the soul suffer first, then the lower ones. The final result of this modification of the character depends upon the individual temperament. "The choleric person is more inclined to fits of passion, the sanguine has a greater tendency to an intense frame of mind, the melancholic person becomes more sombre, and the phlegmatic weaker and more indolent." The complaint which in Egyptian times an anxious father made to his son who drank is still true:2

I am told you leave your books .. .

You stray from road to road;

The smell of beer .. .

The beer drives away the people (from you)

It is the ruin of your soul (?)

You are like a broken rudder on a boat

Which obeys in no direction;

You are like a temple without a god,

You are like a house without bread.

Individual Toxic Disturbances in Alcoholism

The drunkard is always violently oppressed by the burden of alcoholism, and it is of little importance whether and to what degree he is conscious of it. The physically organic injuries depend upon the average amount of alcoholic beverages taken habitually, their concentration and individual resistance. It is therefore useless to try to determine the quantity of alcohol which stamps a person as a drunkard. It is also not possible to ascertain the quantity of lead a workman must absorb during his daily work in order to suffer from grave saturnine poisoning. The same is true with respect to the mercury poisoning contracted in dangerous trades. The gravity of the injurious consequences of alcohol depends largely on the degree of resistance of the individual on account of the mysterious role played by adaptation. That is the reason why in some persons physical or mental troubles appear very rapidly and in others after a much longer period. The regulating functions of which the organism disposes may for years do a great deal to help to maintain the faculty of work in the individual. The prolonged resistance to alcohol of these particularly refractory subjects is said to be promoted by the sleep following the drinking of alcohol. Sleep has been considered as a period of recreation for the organism during which time combustion and elimination take place. I regard this theory as of little interest. On the contrary there are a considerable number of individuals in whom the habit of drinking causes extremely rapid and violent disorders of a physical and mental kind. Among them are women, children, and also persons of superior intellect, especially those with artistic gifts.

Besides the ordinary disturbances of the circulatory system, liver, heart, and kidneys, there is in certain individuals a particularly marked disposition to the evil effects of alcohol, and it appears in the evolution of alcoholism in the form of pathological inebriation or dipsomania. The drinker who is prey to the former is dominated by two strong emotions, fear and choleric temper, which occasionally appear in a violent form without any sign of inebriety and may lead to crime. I have been asked for an expert opinion in cases of this kind, and in one of them, which caused a great stir in South Germany a few years ago, my testimony was such that a physician who had murdered his brother-in-law was not prosecuted.

Dipsomania is a kind of intermittent inebriety. It has been described as mental epilepsy, owing to an erroneous interpretation of the symptoms. It is characterized by a state of depressive melancholia of short duration accompanied by a violent craving for alcohol which leads to excesses of the latter. This violent craving for alcohol destined to alleviate the state of depression has its origin in a constitutional anomaly.

A Glance at Alcohol in the Past

Unfortunately we are furnished daily at the present time with a great abundance of documentary evidence regarding the organic and mental alterations due to alcohol. The past supplies no less. Among those men whose names the history of the world has handed down to posterity, among those much more numerous, even countless men who, born in darkness, lived in obscurity and disappeared without leaving more trace than a fleeting shadow, there have been many who, incapable of resisting the passion for drinking spirituous liquors, became victims of the habit, and through their drunkenness brought much evil into the world wherever they had the opportunity or the power.

The history of alcohol is bound up with that of peoples and kings. No human document, however ancient it may be, is old enough to indicate the beginning of the evil. The first users of alcohol were the first to abuse it, because reason and folly are both attributes of human nature and their manifestations are parallel. It is not within everyone's intellectual range to foresee the ends of things and to judge the balance of causes and effects, especially when sensual pleasures and impressions play their part. At all epochs sometimes one people, sometimes another, had the reputation of indulging excessively in the habit of drinking. Documents dating from the primitive ages of humanity, exhortations, legal measures establish the truth of this statement; it is, however, difficult to ascertain whether these measures were directed against the general use of alcohol or merely its abuse.

The Biblical accounts of the effect of alcohol coincide also with our experience. Besides descriptions of grave intoxication and its consequences, at the beginning of the eighth century before our era warnings appear against the injurious consequences of inebriety. They can be found in the Proverbs of Solomon, in Isaiah, Jeremiah, Amos, and Hosea. No doubt drunkenness was far from rare at those times, and its general consequences were well known:

Wine and women make wise men fall off.

Woe unto them that rise up early in the morning, that they may

follow strong drink; that continue until night, till wine inflame them!

Isaiah refers to drunkards in these words. Without a description of the effects of wine they can even be recognized as such.

Or the biting irony:

Woe unto them that are mighty to drink wine, and men of strength to mingle strong drink!

The reproach of intemperance was occasionally made against the tribe of Ephraim by the same prophet:

Woe to the crown of pride, to the drunkards of Ephraim, whose glorious beauty is a fading flower!

Special allusions to its harmful consequences to the organism are also not lacking, for instance with regard to gastric disorders, mobility, disturbances of vision, and hallucinations.

But they also have erred through wine and through strong drink are out of the way; the priest and the prophet have erred through strong drink, they are swallowed up of wine, they are out of the way through strong drink; they err envision, they stumble in judgment.

For all tables are full of vomit and filthiness, so that there is no place clean.

Who hath woe? Who hath sorrow? Who hath contentions? Who hath babbling? Who hath wounds without cause? Who hath redness of eyes?

Thine eyes shall behold strange women, and thine heart shall utter perverse things.

The drinker of old made light of the advice of others and the warning signals of his body just as does the drinker of to-day. Punishment and shame do not fright the slave of alcohol:

They strike me, I feel no pain. They beat me, I feel nothing. Then I shall awake and indulge in it (wine) again.

Not only wine but also liquors similar to brandy were employed. The word om, which is used in Proverbs and in Isaiah, refers to very powerful alcoholic beverages mixed with spices and therefore containing essential oils.

Wherever a substance with the properties of alcohol was discovered, its abuse and the consequences thereof did not fail to appear. In Egypt wine and beer were consumed. The use of both is described in the earliest accounts. The hieroglyph of a wine press already appears, according to Flinders Petrie, in the middle of the First Dynasty under the reign of Den-Semti. Wine was demanded at social meetings. No condemnation of drunkenness occurs before the Nineteenth Dynasty. In the Seventeenth Dynasty a servant asks a guest to drink, to drink to intoxication: "Be of a festive disposition!" And the lady says: "Give me eighteen vessels of wine: you see, I love drunkenness!" The alcoholic beverages of the Egyptians did not lack variety. A glance at the bill of fare on the tombs informs us that the dead demanded no less than six kinds of wine and four of beer. There were many exhortations and warnings to the living and especially to the youth of Egypt, as I have already stated.

With respect to Greece and the Roman Empire, that nauseous fen wherein sat a whole population in churlish and immoral putrefaction, the writers of those times have depicted drunkenness in a hideous but doubtless true manner. In the refined circles of the rich classes drunkenness was more shamefully and repugnantly indulged in than elsewhere at that time.

But Christians too gave rise to scandal by indulging to excess in alcoholic beverages. The apostle St. Paul bears witness that some of them had so little mastery of themselves as to become drunk during the love-feasts celebrated in common. Novatian, the Father of the Church, in the third century speaks of Christians who in the morning, after fasting, began the day by drinking, and poured wine into their still "empty veins," and are drunk before they have eaten. "They do not go to the taverns, but are taverns in themselves, and their pleasure is drinking." And what do the drinking vessels signify which are discovered in the catacombs? They are of glass, and flat, and engraved or painted in gold with pictures of saints, or short inscriptions, such as the names of these saints or "bibe in pace."

Alcohol was and is still abused throughout the world from East to West. In the Rig-Veda, which was honoured as a divine revelation, the inebriating drink of the Indian is mentioned, that much-discussed soma,' whose mode of preparation has so far not been discovered. I regard soma as a very strong alcoholic beverage obtained by fermentation of a plant worshipped like the plant itself. Sura seems to be a kind of brandy. According to Strabo they drank a wine made from rice instead of barley, which must have been similar to arrack. Distilleries existed at that time which satisfied the taste of the Indians for soma and probably for other alcoholic beverages such as kilala and parisrut. Drunkenness therefore doubtless existed with all its consequences, the most serious of which were regarded by the sura drinker as "outrages against the gods."

I should only be repeating in different terms what I have already stated if I attempted to describe in detail the state of alcoholism during the succeeding centuries down to the present day. Indeed, nothing has changed with respect to man and his bad instincts, his desires and their outward manifestations. Manners, customs, and dress may change, but the aberrations of moral consciousness, including the faculty of self-judgment, will never disappear from humanity, any more than will the good qualities. The drunkenness of the Germanic tribes, who did not abandon their liking for alcohol after their conversion to Christianity, that of the Goths in the sixth century, that of the Franks at their feasts in which the women also took part, the intemperance not only of the common people but also of the monks and clergy in the ninth century against which Charlemagne issued a capitulary, the alcoholic debauchery of the following centuries, especially the first half of the sixteenth century, the great period of alcoholism in Germany, satirically described by Sebastian Brandt, and finally all that recent centuries have shown us with respect to inebriety firmly establishes the fundamental truth that abuse is the brother of use, and it matters little whether this principle be applied to the question of right, power, liberty, love, play, purging and bleeding, eating, or the use of alcoholic beverages. However, in no case does use incline more to abuse than in that of narcotic or stimulating substances. The peculiar influences exercised by alcohol on the functions of the brain on the one hand and individual sensibility on the other explain, as I have already pointed out, the character and range of the injurious effects which result from its abuse, the obstinate perseverance in the vice, and the praise of alcohol even if it brings death. A characteristic example of this last is the epitaph of a drunkard in a church in Florence:

Wine, which gives life, to me gave death. Sober I never saw the dawn—

Now my very bones are thirsty!

Wanderer! Besprinkle the tomb with wine, Empty the cup, and go!

Farewell, ye drinkers!

Often social misery gives rise to drunkenness and the latter again to social misery, and to human wretchedness in general where it had not existed before. Whole strata of society may become victims of alcoholism. But the pages of history point out other facts: how the great ones of the earth who were able to exercise a decisive influence on the destiny of mankind have indirectly led individuals or nations to misery or ruin by their drunkenness. This has occurred frequently in such a way that few were unable to perceive the chain of events. But in other cases only the medical specialist is in a position to re-establish the facts and their initial cause. Volumes might be filled with proofs of the influence of alcohol in history from a medical point of view. Antiochus Epiphanes (i.e. the Famous) was called on account of the actions he performed in a state of inebriety, "Epimanes," i.e. the Furious, and was overcome by the Maccabees. Philip of Macedon was a drinker, and his son, Alexander the Great, who was an excessive alcoholic, frequently spent two days and nights in a state of intoxication. He committed many misdeeds during dipsomaniac crises and found through alcohol a premature death. King Antigonus was a drinker, and Dionysius the younger, the Sicilian tyrant, was said to remain in a state of intoxication for three months on end, which resulted in visual disturbances. Darius, the son of Hystaspes, had it inscribed on his tomb that he could drink large amounts of wine without inconvenience:

.

. . 4 Suva/Inv xai oivov riven/ KoAbv rod rouvrov Oepetv g . .

Tiberius was called Biberius on account of his drinking excesses. Caligula, Claudius, Nero, and probably Trajan also were drinkers. The emperors of the later empire, too, Heliogabalus, Galerius, Maximin, drank to excess, and Jovian succumbed in his chamber to the poisonous effects of carbon monoxide gas during one of his frequent drinking bouts. Other Roman and Byzantine potentates have hardly ever suspected the connection of alcoholism with historical crimes and misdeeds. There have always been crowned drunkards in the world, in France, England, Germany, Russia; King Wenceslaus, son of the Emperor Charles IV, competed with many other monarchs, for instance the Emperor Peter the Great, or Elizabeth of Russia, who drank day and night and was usually drunk. More recently the converted pagan "king" Pomare II, who translated the Bible into Polynesian and constructed a church 712 feet long, went to work with the Bible under one arm and a bottle of rum under the other.

Quite as many drunkards can be encountered among the Popes, for example Alexander V, Sixtus V, Nicholas V, Leo X, and many of those who resided at Avignon. Drunkenness had penetrated at a very early date into the ranks of the clergy, according to the exhortations of Saint Jerome. The councils of Carthage, Tours, Worms, Treves, etc., raised an outcry against this state of affairs. Erasmus of Rotterdam said of his epoch: Monachorum nihil aliud est, quam facere (!), esse, bibere. And how many of those who, in their day, followed with understanding and sagacity in the Lord's footsteps, how many of those who thanks to their genius created immortal works, must be placed among the drunkards! These true heroes of the world finally paid their tribute to alcohol with their lives because they acted according to the terms of the epitaph of Epigonus on a frog who had fallen into a wine-barrel:

. . . 436 TIVEc 15(5wp

ai'vovot, itavinv o-coeppova ktatvottevot.

Woe unto those who commit the wise folly of drinking water!

Alcoholic Beverages

All these and the many other drinkers of present and past times who in some way or other exercised an influence on their epoch or the life of their time which to a greater or lesser degree bears on the present and the future made and continue to make use of alcoholic beverages of very different kinds, all of which contained ethyl alcohol. Besides this other alcohols and numerous substances resulting from the mode of preparation or intentionally added were also present. Ammianus Marcellinus reports that the Gauls of the fourth century had no wine in their country although they eagerly desired it. But they prepared other beverages which had effects similar to wine: Vini avidum genus adfectans ad vini similitudinem multiplices potus . A large volume would not suffice to describe the alcoholic beverages of the past and present. It is nevertheless necessary to give some characteristic examples of man's contrivances to obtain alcohol. This may convince those who in their ignorance believe in the possibility of preventing its use.

The variety of the processes applied in the manufacture of alcohol may be based on the three general methods which have been laid down for the first time in the following pages:

(a) The alcoholic fermentation of sugar. This process is the foundation on which the preparation of mead or honey-beer is based. The latter is still extensively in use in Abyssinia (Bioo, Tej of Amhara, Tadi of Oromo), the Galla countries, and in South-West Africa. In the first century Pliny mentions mead as a drink consisting of water and honey. The best wine, he says, is prepared with rain-water which has been previously set aside for five years. Some people, he says, mix one-third of rain-water prepared in this way with one-third of fresh or sometimes boiled water and one-third of old honey. The Edda states that the dwarfs Fjalar and Galar, after having assassinated the wise Koasin, mixed his blood with honey and prepared a beverage which endowed everyone who drank of it with the gift of song. The Scandinavians drank mead avidly. They introduced it into England, and because the cup of mead played an important role in the nuptial ceremonies which lasted for thirty days, the first month after marriage was called the "honeymoon." Attila is said to have died on the eve of his wedding from drinking too much mead.

To this class of preparations belongs also a very ancient alcoholic beverage, palm-wine. Herodotus informs us approximately 420 years before our era that peasants brought on ships to Babylon this wine which he calls Ocnvuditog oivoc. Different species of palms indeed secrete a considerable quantity of a sugary juice if incisions are made in the in florescences or the upper part of the stems. A frequent renewal of the incision is necessary, for the irritation due to the wound seems to augment the flow of the juice. This wine is consumed in great quantities in South and Central America, in Africa (in Tunis, on the banks of the Congo, on the west coast, on the upper reaches of the Niger, in Liberia, in the hinterland of Togo, on the coast of the Loango, on the east coast to Somali and Monbuttuland, and in Tanganyika). It is also consumed in Asia, in Ceylon, India, the Philippines, the Carolines, New Guinea, New Caledonia, the Solomon, Gilbert, Marshall, Ladrone Islands, the New Hebrides, Marquesas, etc. The following palms are most frequently employed for the preparation of the beverage: Raphia vinifera, Elaeis guineensis , Borassus flabelliformis , Arenga saccharifera, Hyphaene coriacea, cocos , Attalea speciosa, Mauritia flexuosa, Phoenix, the date palm.

The banana is also employed in the countries where it grows, for instance in the African lake district, nera the somerset Nile, in Masailand. The Warundi, for example, daily indulge in excessive drinking of banana-wine.

The agaves are also used for the preparation of alcoholic beverages according to the report of Sahagun, the most important historian of America. These products are called pulque or med. The saccharine juice is obtained by incisions in the floral stem which is then left to ferment. Several million South Americans, as well as Mexicans, drink pulque.

Instead of agaves the juice of certain cacti is utilized for the preparation of fermented beverages, for instance cereus giganteus (drunk by Indians and Mexicans in Sonora and Lower California), opuntia tuna (whose produce is called cononche), and opuntia ficus indica.

In those regions where the sugar-cane grows it is employed for the same purpose, for instance among the Bangala and the Bashilanga in Africa, where it is called massanga, in Surinam, the West Indies, etc. In those countries where nature does not supply succhariferous plants instinct has led man to employ substances whose sugar content was ascertained thousands of years later by science. The peoples which inhabit the country between the Caspian Sea in Mongolia and Eastern Siberia, the Kirghiz, Tekinzes, Buriats, Mongols, Tungus, etc., have long known how to prepare alcoholic beverages whose origin is concealed in the obscurity of the past. They used for this purpose mare's milk, the lactose (sugar of milk) of which is transformed into fermentable sugar. In this way they obtained kumiss with 1.5 to 3 per cent alcohol. The latter is consumed a great deal by the Tekinzes in the oasis of Mery and is called chat, in Armenia mazun, and in the language of the Tartars katish. The Creek Zemarchus who was sent as ambassador by the Emperor Justin II in 568 to the Turkish Khan Dizabulus in Central Asia narrates that during the feast given in his honour large quantities of a barbaric beverage called kosmos were consumed. Priscus whom the Emperor Theodosius II sent to Attila also mentions a similar liquor called kamos.

In the same manner kefyr or other fermentative mycelial symbioses produce alcoholic milk beverages, for instance the Armenian mazun.

(b) In all the preparations described hitherto the sugar utilized for the fermentation was already present in the substances employed. The second of the general methods adopted in order to obtain alcoholic beverages consists in the transformation into dextrose or maltose of the starch contained in vegetable matter. This process was unconsciously applied by man from the most ancient times.The oldest plant used with this end in view seems to have been millet, whose cultivation is considered an indication of a state of semi-civilization which was succeeded by the use of the plough. With the aid of eleusine corocana, whose starch content is very large, an alcoholic millet beer is prepared, for instance among the ASande of the Congo (batossi) sometimes together with sorghum. It is also prepared among the Indians (bojah or bojali) and in the Mahratta States, in Sikkim (marva), from there to the east in Bhutan, between Assam and Tibet in the kingdom of Dharma, and to a lesser degree in Nepal.

A beer prepared from sorghum vulgare is extensively employed in Africa. The names given to sorghum are durrha, duchn, and mtama. It is the millet of the Negroes, the Moore, and the Kaffirs. The beverage is already consumed on the banks of the upper Nile (bilbil merissa), in East Africa, in Somaliland as inebriating liquor, pombe, and in a non-inebriating form as togwa, in Harar (bosa, kuhija), Abyssinia (dalla, soa), in the Congo territory (pombe, bussera, malafu), and southward to the Portuguese possessions, in the Sudan (merissa, dawa, bosa), and in South Africa (oala, boyaloa).

Probably more recent than millet-beer is that prepared from barley, which seems to have originated in Egypt and in the course of thousands of years spread more and more to the west and north. Strabo states that the Ethiopians still employed it with millet. At the beginning of the seventh century Isidore of Seville writes in his Origines of the use of barley as a substitute for wine in Spain. The oldest beer was prepared without hops. In the German monasteries the fabrication of beer was also improved with respect to the keeping properties of the beverage. Barley was chiefly employed, as its name indicates, for according to Grimm bere is the ancient Saxon name for barley. In old High German it is pior, in Norse eolo, in Anglo-Saxon "ale" and "beer." The use of beer as a daily beverage was quite general in the monasteries. Towns had their breweries and malthouses, for instance the town of Freiburg had in 1653 six of the latter and twelve of the former. Especially in the sixteenth century the civil and ecclesiastical courts rivalled the private breweries in the manufacture of beer. In the towns there were primitive house-breweries for the use of the inhabitants and of strangers. In some towns, for instance Hamburg and Lubeck, beer was prepared from wheat and called "white beer." The following figures will convey an idea of the magnitude of the consumption of beer in various countries at the present day. In London about a million and a half quarts of English beer are consumed daily. In Bavaria the consumption is estimated at two hundred and twenty litres per head annually. In all Germany five thousand million litres are manufactured every year.

In distant countries, for example Tibet, a mild beer called chang is prepared from barley. This is distilled and a very strong product, arrack, is obtained, not to be confounded with the rum of the same name.

Among the Dyaks of Borneo (tuak) , in Formosa, and to a very large extent in Japan, rice is employed for the manufacture of alcohol by fermentation. It is stated that sake or rice-wine was prepared so long as 2,600 years ago. Detailed reports of its use are forthcoming from the year 90 B.C. The transformation of the starch of rice into sugar and its alcoholic fermentation are due to certain yeast-cells and hyphomycetes (koji). In China sake is also employed. In Pekin there are rice-wine breweries.

Central and South America have their own particular alcoholic beverages. In these countries it is maize which is utilized for the purpose of obtaining alcohol. It is first boiled, then masticated or chewed. The masticated substance is placed in large earthenware pots, covered with leaves, and left to ferment. Reports of this process date from the year 1526. The use of this maize-beer, chicha and cangiii, extends from Mexico to Guatemala, Yucatan, and Darien to the high plateau of Bogota in the south, and is also found among the inhabitants of the Andes, in Ecuador, Peru and Chile to Araucania and eastwards from the Orinoco, and in Guiana as far as the territory of the Amazon. It is the national beverage of the Indians of the Guarani group, especially the Abas or Chiriguanos, and the half-civilized Indians of the Andes, the Quichuas, Aymara, Coroados, etc. Here the manufacturing process consists in the transformation of the maize-starch into dextrine and sugar and the fermentation of the latter. A yellowish, sourish, and fairly inebriating liquid is thus obtained resembling new wine. During the period of Christianization of Peru, etc., exhortations as to the abuse of chicha formed a large part of the sermons of the missionaries. "Chichinism" is not a special disease, but a grave form of alcoholism due to the substances contained in the beverage. Certain peculiar morbid states following on the drinking of chicha, as for instance the frequently observed spots on the hands, occasionally also occur after the consumption of other alcoholic beverages.

The Indians who speak the Quichua language in the mountainous territory of Ecuador prepare their beer from maize (asua) by boiling and crushing the plant, which, placed in hermetically sealed receptacles, furnishes sugar and afterwards alcohol through the action of ferments present in the substance.

Another method of obtaining alcoholic beverages has been adopted in South America. Jatropha manihot, the kassava tree, contains a large amount of starch, which is known as mandioca, tapioca, or Brazilian arrowroot, as well as a juice rich in hydrocyanic acid. This juice is pressed out and removed and the starch is transformed into sugar ready for fermentation. Here we have another instance where we must admire the ingenuity of the primitive instinct of man which taught him this method of manufacture long before it was scientifically explained. The natives boil the mandioca, the women chew the substance and spit it into a receptacle. The saliva transforms the starch into sugar and the ferments transform the sugar into alcohol. The resulting beverage is called paiwari or paiva in British Guiana, taroba on the Tapajos, caysitma in Ega, cachiri among the Roucouyennes, cauim or pajuani among the aborigines of Brazil. The use of this beverage extends eastward from the territory to the west of the Magdalena to about 50 degrees west longitude, northward to the Caribbean Sea and south to the Amazon and the upper reaches of the Tapaj6s.

The transformation of starch into sugar by means of saliva is also practised among other isolated tribes, for instance in Formosa with rice and in South America with yucca, probably Yucca angustifolia (Yucca glauca, Yucca filamentosa) .

This plant is frequently used for food as well as for the preparation of a very popular beverage. For many tribes, the Jibaros and the Canelos Indians in the east of Ecuador, for instance, the Cholones on the upper reaches of the Huallaga, etc., yucca-beer plays a more important part than does the algorobo-beer for the chaco Indians or maize-beer for the Chiriguanos and the Quichuas. The fruit is boiled; it would seem that the Cholones employ the root. A part of the boiled substance is chewed by the women on specially appointed days and thoroughly triturated with saliva; the remainder is merely crushed. The whole mass is then placed in an earthenware jug and left to ferment. In twenty-four hours it is ready for use. It is drunk diluted with water. The Indian on his wanderings carries some of the yucca-substance with him wrapped in banana leaves. By adding water he obtains a mildly inebriating beer of a colour similar to milk which enables him to go without food in cases of emergency. This beverage is consumed at certain drinking feasts. On these occasions the Indian reveals not only his taste for this beverage but also his peculiar religious conceptions.

These conceptions are attached to certain ceremonies as well as to the beverage itself. During the fermentation of the substance in the earthenware jugs Karsten observed Indian women squatting round the vessels singing magic chants which are said to contribute to the success of the process. Later, while the chicha, yucca-beer, or other similar beverages are imbibed, dancing and singing ceremonies of various kinds take place. They begin before the onset of inebriety sets in and are continued during the drunken state.

The Indians of Ecuador in the same way prepare a beer from the fruit of the chonta-palm Guilelma speciosa (the chuntaruru of the Canelos Indians, the ui of the Jibaros) which they cultivate. The preparation and consumption of this beer are likewise accompanied by ceremonies.

Another substance which furnishes an alcoholic beverage is the algorobo from the fruits of the leguminous plants Prosopis alba, Prosopis pallida,4 Prosopis juliflora. The Indians of Ecuador, Paraguay, and the northern parts of the Argentine—all the tribes of the Gran Chaco—impatiently await the ripening of the fruits, which also serve as an important food. The Matacos, Chorotis, Ashluslay, etc., have all kinds of ceremonies for the chasing away of evil spirits who may impede the ripening of the plant. The ripe seeds with the pulp of the fruit are masticated and mixed with saliva. After being soaked in very hot water the substance is left to ferment in a goatskin. This process is accompanied by chanting and the beating of drums in order to drive away harmful demons. The men alone drink the product to complete inebriety. The same results are obtained from a beer of Acacia aroma (tusca) or Gourliea decorticans (chanar), a fruit tree with plum-like fruits, or Tizyphus mistol (mistol) , whose fruits, resembling over-ripe grapes, are prepared in the way already indicated, by being masticated and mixed with saliva. All these beverages are considered to increase physical strength in a marked manner.

We must now leave these primitive alcoholic beverages of distant countries, whose only European analogy would seem to be the Russian kvas, prepared by acid and alcoholic fermentation from wheat, rye, barley, buckwheat flour, and bread, and pass on to other beverages used in various lands, consisting of purer and more concentrated alcohol.

(c) The third method, the distillation of alcoholic liquors, answers to a more advanced scientific development. In those cases where this method was employed by Asiatic peoples of an inferior degree of civilization they probably gained the knowledge from Europeans or in some cases even from the Chinese. Weak alcoholic beverages did not give satisfaction, and were replaced by spirits.

The Buryats drug themselves with milk-spirits obtained by distillation. The Kalmuks and Tartars make use of an arrack prepared from milk. The Tekinzes of the oasis of Mery employ chal, a product of the distillation of camel's or cow's milk, which is suitably treated.

In the Far East large quantities of rice-spirit are manufactured. The name of this beverage in China is samshu.5 According to whether it has been distilled once, twice, or three times it is called Mei Chau (Leu Pun Chau), Sheung Ching Chau, or Sam Ching Chau. Its alcoholic content varies from 50 to 60 per cent. The Chinwan of Formosa, the Gilyaks, the Kakhyen of the Khasia mountains, and many other tribes make use of this intoxicant. A Chinese spirit is also prepared from millet, usually Sorghum vulgare. Special factories in Manchuria produce more than two million vedro of chanshin every year. In some districts the people prepare it at home with primitive implements. On account of their cheapness these spirits, defying all interdictions, have penetrated into the Amur and Transbaikal territory. It is said that this beverage produces two inebriations. On the day following the consumption of a large quantity of the spirit intense thirst is experienced, and on drinking a glass of water a second state of inebriation supervenes, more violent and of longer duration than the first. Chinese spirits contain a considerable amount of fusel oil. We find in different parts of the earth an innumerable variety of distilled spirits for its many hundred million people. Where potatoes, corn, grapes, etc., are not available man takes other substances containing starch or sugar and prepares distilled spirits by extremely primitive means. In Central Asia, for instance, besides rice, Sorghum vulgare is utilized, its seeds serving the Karens of Burma for the preparation of spirits. Less known plants, however, are also employed for this purpose. The inhabitants of Kamchatka manufacture a very powerful distilled product resembling spirits from Heracleum spondylium, hogweed, by letting the stems ferment. The natives of Honolulu use the roots of Cordyline terminalis (tishualh) to the same end. The Tahitians, the natives of the Tuba and Sandwich Islands, and the Maoris employ Cordyline australis, or more often at the present day bread-fruit, pineapple, and orange juice. The inhabitants of Tasmania use the berries of Cissus antarctica, the Hottentots the fruits of the Grewia species, the Indians the blossoms of Bassia latifolia (mahwci, mahua) . The Indians of Eastern Ecuador obtain an alcoholic liquor from the distillation of roasted yucca fruits. In Germany and other countries Sorbus aucuparia, rowan, Sambucus, etc., are occasionally used.

The other artificial preparations on a basis of more or less pure alcohol manufactured in civilized countries and also in use in noncivilized areas are extremely varied mixtures containing essential oils or other substances. Their stimulating effects on the palate and the brain differ in character and intensity. For the most part they contain many injurious secondary substances (fusel oil, aldehydes, furfurol, etc.) so that they play an extremely important part from the toxicological standpoint when their use is chronic and the individual limits of resistance have been exceeded. This may be said of absinthe, a beverage now prohibited in France, an alcoholic solution of essential oil of absinthe. The countless drinks mixed by bartenders are frequently nothing other than alcoholic solutions of essential oils. These beverages are also prepared at the counter by women, who, like the Circe of Homer, transform men into pigs. Eau de Cologne is used by drinkers in Africa (Tabora, Zanzibar), British India, America, and Europe. It is even preferred to rum, brandy, and other liquors of the same kind. A liquor prepared with Capsicum annuum, Cayenne pepper, should be included here. It appears to have a very distressing influence on the drinker.

To some Chinese beverages the root of Sophoratomentosa, which contains cytisine, is added. This has very exciting properties. It is stated that in the district of San Antonio (Texas) the Indians used and still use the seeds of Sophora secundiflora in doses of half a seed in order to become intoxicated. A state of gaiety is succeeded, according to reports, by two to three days of sleep.

With the aid of Epilobium angustifolium and many other plants alcoholic beverages are prepared all the world over, which exercise diverse influences on the brain. They all contain, besides alcohol, other substances, essential oils, etc., which reinforce or modify the injurious action of the alcohol.

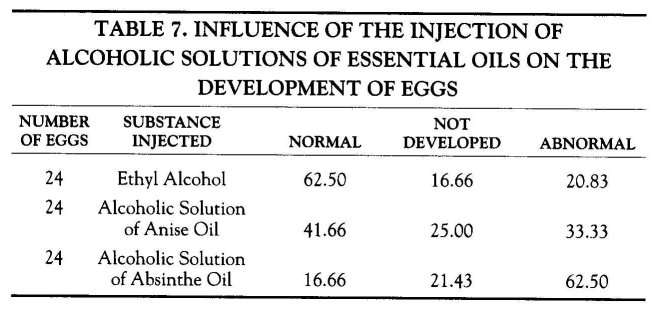

I have described the action of alcohol on the development of fertilized eggs. Table 7 shows how essential oils of the kind mentioned above influence this development.

Certain conclusions may be drawn from this table. In practice its immediate significance for man is not very large. However, it may always be asserted that the effect of alcohol on a drinker is more noxious if essential oils are added which are liable to act in a different manner from the alcohol itself. If such extremely injurious substances as nitrobenzene are added to spirits in order to render them more intoxicating and palatable, we must regard it as a deplorable practice from every point of view. It is claimed that on account of its furfurol and higher alcoholic content brandy is more injurious in animal experiments than ethyl alcohol.

The aggravating effects due to the presence of essential oils in addition to alcohol have been experimentally ascertained hundreds of years ago. It was discovered that if rosmarine was added to beer during its manufacture a product was obtained which gave rise not only to headache but even to stupor. From early Roman times to the seventeenth century so-called mixed wines (i.e. wines which had added to them essential oils from organic material such as rosmarine, fennel, anise, absinthe, euphrasy, sage, and hyssop) were consumed. Claret is such an aromatic wine. It is prepared from honey, clove, grains of paradise (Amomum melegueta rosc.), cinnamon bark, and ginger. In the eighteenth century the famous drink hippocrass was still made from wine with cinnamon, pimento, clove, nutmeg, ginger, and pieces of greengages; or sometimes with the addition of almonds, musk, and amber. Pliny states that in the beginning of the Roman Empire not only were aromatic plants employed in the manufacture of perfumed wines, but also the evil Mandragora, which suffices by itself to produce a state of somnolence. The action on the brain of these aromatic wines (vina odoure condita) which are still used at the present day is an unpleasantly reinforced alcoholic action, even if the effects are not experienced immediately.

It is therefore not only the quantity which in the long run injures the body and the soul of the drunkard, but also, and to an even greater extent, the composition of the beverage. Some kinds of wine are even more noxious than certain spirits. One wine of this kind, the Est of Montefiascone, will never be forgotten. The nobleman Johann von Fugger, who was a drunkard, caused a servant always to ride in advance of him and write on the door of every tavern where he found good wine Est (here!). At Montefiascone he wrote Est three times. His master arrived, and drank so much that he died. On his tomb, which is said to be still in existence, the following words were inscribed by his servant:

Est, est, est, propter nimium est Dominus meus mortuus est.

Here, here, here, too much of this "here" My master drank, so now he lies here.

Temperance and Abstinence

In the preceding pages I have given a sufficiently clear and precise description of my conception of alcoholism. It is founded on toxicology, on what I have myself seen and my own experiences as an expert. It is unnecessary to copy statistical records of the increase of alcoholism in civilized and savage countries and its harmful effects on the people, or to lay stress on its well-known social consequences, domestic misery, poverty, degradation, and so on. The far-reaching import of this evil is clear to everyone, without further explanation; it is clear also that if alcoholism were abolished some little happiness would be created despite the continuance of many even greater miseries on earth. No period of history has been free from attempts to combat alcoholism on a larger or smaller scale. Individuals and groups addressed its devotees in the language of religion, common sense and reason, and by means of laws and regulations. They even attempted altogether to suppress alcohol for consumption. For the reasons which I set forth when dealing with morphia these efforts were of little or no avail, with the exception of those of Mohammedanism, which for several centuries kept its believers from alcohol but could not prevent the use of equivalent substances. Moreover, the words of Mohammed are nowadays frequently vain on account of the spread of civilization and the influence of Western modes of living on the Orient. The mighty energy of the powerful modern alcoholic beverages has vanquished the instructions of the Prophet. It is therefore not improper to speak of an increasing alcoholization of the Orient, even if we admit that popular belief still considers the use of alcohol as an infringement of the law. The same is the case with the Hindus. This people is naturally sober and temperate. No decent Hindu will drink spirits, which are as rigorously prohibited as is, for instance, the eating of beef. Nevertheless, here also alcohol and many other substances which should not have made their way have overturned ancient custom. The Methodist sect also practices complete abstinence from alcoholic beverages.

At the present day the ancient and multiform combat against alcoholism shows itself in a new form. It is directed chiefly against alcohol in itself. By "psycho-scientific" processes all its physiological effects are transformed into sins. Minute experiments prove that not only is drunkenness an evil, but that everyone who drinks alcohol in whatever quantity is a dangerous person. The band of abstainers, though as old as the world itself, was formerly not a very large one. At the present day it has become more important, and many of its members, convinced apostles of its principles, carry forth in speech and in writing the gospel of abstinence.

I respect those who for one reason or another abstain from alcohol just as I do those who live in conformity with religious prescriptions, such as the observance of Ramadan, the Mohammedan month of fasting, the keeping of a vow or some form of asceticism, vegetarianism, antinicotinism, etc. It is a private matter for the individual, as is the abstinence from alcohol. The individual may have his own reasons for its justification, just as he may have for not eating such and such a food. But to condemn the general effects of alcohol and to convert others to this opinion more is needed than subjective reasons, even more than we can read in books and pamphlets. To the majority of abstainers who feel themselves bound to an apostolate, the following words of Lessing can be applied: "Who is there, who, when he believes himself to be enlightened, does not desire to enlighten others? The most ignorant, the greatest fools, exhibit the greatest ardour. This may be seen at all times. A shallow brain gets some vague notion of a science or an art, and babbles of it on all occasions."

In this sphere, as in others in our days, suggestive slogans are employed. "Pay by Post" is inscribed in lapidary letters on the post office. Patent bed manufacturers tell us to "Sleep Patent," gas companies to "Cook with Gas!", shoe factories adjure us "No more Cold Feet!" Why "No more Alcohol!"? It is nothing but a slogan, a mere phrase. Why such an expenditure of efforts against alcohol alone, where there are other deeper cravings which well deserve some apostolic effort? Why is there no general crusade against morphia, cocaine, nicotine, caffeine, lust, gambling? The anti-alcoholic fight is based on no clear judgment; it is conducted with party-spirit. Its leaders are for the most part laymen, though professors of medicine also take part in it. But when these latter have once adopted an erroneous point of view their obstinacy is unrivalled. No opinion can be derived from psychological investigations, but only from science, a science founded on the observation of facts; and this, as I have already stated, is lacking.

We smile at the reasons given in ancient times for total abstinence from alcohol. Certain Christian sects, the Encratites, the Tatianists, the Marcionites, and the Water-drinkers, considered the consumption of wine a sin; the Servians said that the devil after having been expelled from heaven transformed himself into a snake and mixed with the earth, the product of this mixture being the vine. The stems, the snake-like arms of the vine proved its diabolic origin. But it is more than ridiculous to state at the present day that alcohol is "poison for the human race which eventually leads to the degeneration of whole classes of society," or that it is "in all circumstances a poison in the ordinary sense of the word," or even that "the consumption of a single glass of wine or beer diminishes the intellectual faculties," that "alcohol shortens life in general and especially that part of it which is economically profitable." The greatest nonsense of all, manifesting the supremest ignorance of the facts, is the statement that "the life of abstemious persons is of longer duration than that of even moderate drinkers," and so on.

Were this so, the compelling question arises: to whom does the world of to-day owe its form and its activity, to abstainers or to nonabstainers? To the latter alone, without doubt. They have been the creators and promoters of science. To them we owe the beautiful creations of art. They have supplied the wonderful feats of the poetic imagination, and the noble productions of music have been forthcoming from the profound depths of their sensibility. They have discovered by calculation the presence of new worlds in the far-off spaces of the universe, and later on even perceived them. Their ingenuity solved for them many enigmas posed by the existence of things, and they have foretold the present and the future as if informed by a divine inspiration. Non-abstainers launched speech on its journey across terrestrial space on the waves of the ether. Zealous and inspired with the joy of discovery they have opened roads on this globe which but for them would never have been trodden. Even if among this multitude of the elect one or another, through bodily weakness, has renounced alcohol, what is this in comparison with all the others who are indebted to this stimulant not only for hours of joy but frequently for the impulse to their contribution to the well-being of mankind?

It is incomprehensible and indefensible that abstainers should consider a man who has a liking for wine as an inferior creature. Even if he drinks it in considerable quantities there is not the least reason for this view, especially when he has given precious and lasting gifts to mankind. The Apostle Paul says: "Let not him that eateth despise him that eateth not; and let not him which eateth not judge him that eateth." A Heidelberg mathematician once told me the following story. One day as he was ascending the Schlossberg with a Heidelberg philosopher the latter suddenly left his side because he did not want to pass before the statue of a drunkard. The "drunkard" was no other than Victor von Scheffel! We also read that Goethe was possessed with the demon of alcohol. This is said to be the reason why his family after the third generation was destined to become extinct. This is the false invention of an ignorant and fanatical abstainer. Even were it true, however, the name "Goethe" of itself would transform into praise the accusation of incurable imbecility hurled at wine-drinkers, just as in the Scriptures water was transformed into wine by Jesus, who was also Himself accused of drunkenness because he appreciated wine. As a matter of fact, Goethe's son inherited alcoholism from his grandfather, Vulpius, whose drunkenness reduced his family to misery,

and who frequently pawned his clothes to obtain money for drinking. Goethe's wife, Christiane Vulpius, in later years gave many proofs of her pernicious inheritance. His son August followed her example to such an extent that he deserved the name of drunkard. Frau von Stein reports that one evening he drank seventeen glasses of champagne at a club.

In my capacity as pharmacologist and toxicologist I wholly reject those experiments which have led certain psycho-physicians to conclude that alcohol in any quantity, however small, intoxicates the brain. Such experiments may be very interesting, but their value is completely insignificant when compared to the facts of common knowledge which are the result of everyday experience of the effects of alcohol in moderate doses. These psychophysical experiments can be compared, for instance, to the experimental treatment of healthy subjects with homoeopathic medicines. In both cases the tests are carried out on persons who, merely because they were subjects of the experiments, were under the influence of suggestion and therefore wished to furnish interesting reports. The numerous symptoms, among them grave organic disorders, which are said to have appeared after homoeopathic treatment with water that had for some time been in contact with pure gold should be considered in the light of the fact that millions of persons permanently carry gold in their mouths in the form of fillings or crowns for their teeth. But I would go further, and declare that if errors due to suggestion were ignored, the experiments made to ascertain the action of small quantities of alcohol on the brain with respect to the fundamental character of the personality, the capacity for work, excitability, resistance to fatigue, etc., are valid only for their subjects.

Those psychologists who come to other conclusions are in my opinion ignorant of real life. They should, as I have been doing for more than twenty years, observe and investigate the different degrees and varieties of individual sensibility to alcohol, of skilled and ordinary workmen in factories. If the output of work before and after the consumption of three-tenths of a litre of beer were measured, nothing or very little of the results of the so-called general psychological experiments made on a few individuals would remain valid. And this is just the quantity of beer, according to the psychological decision, which, after an initial diminution of the mental reaction, gives rise to dullness of the perceptive faculties. Thousands of brain-workers drink wine of an evening without experiencing, apart from an appreciable brain-stimulation, any "paralysing" effects. The statement that the effects of alcohol, which are usually considered as the effects of excitation (mental excitation, amplification of the output of the heart, suppression of the feeling of fatigue, etc.) are all fundamentally phenomena of paralysis, violates the most elementary truths of biology. It is absurd to attribute a paralysing effect to alcohol and even more so to attempt to support this assumption by elaborate experiments. It is a source of error both for medical men unskilled in pharmacology and for the general public. They have the impression that these experiments are constants, whereas they are, as I have explained, nothing but unimportant investigations on biased and easily influenced subjects.

To believe that the effects of ethyl alcohol on the psyche are the same in all individuals is a fundamental error. This assertion is without any foundation in the case of those who take, even daily, a moderate dose of alcohol, provided it is kept within the limits which their individual sensibility permits them to tolerate, and it is only of relative significance in the case of those who exceed these limits. Perusal of my work on the secondary effects of medicinal substances will show that on every page there are facts to prove that the influence of personality renders illusory every fixation or preconceived determination of the effects on the body of a chemical substance.

It is a general opinion of abstainers, which has become an axiom, that alcohol paralyses the higher mental functions, diminishes the quality of intellectual work, the sharpness and accuracy of conception, the clearness of judgment, and the faculties of memory. We must refute this opinion not only on account of the importance of the personal factor, but also on the grounds stated above. While no one will doubt that it holds good for a person in a state of drunkenness, in this general and apodictic form it is not even applicable to a drinker or a drunkard. I have already pointed out the irrelevance of psychological experimental methods which claim to prove the deteriorating effect of small doses of alcohol on the brain, for instance in the following manner. Is a person capable of learning by heart 25 verses of the Odyssey after taken 25 c.c. of alcohol? I am sure that even without alcohol I should be incapable of accomplishing this feat, although I have an excellent memory for facts in my own special sphere of knowledge and in kindred sciences, such as chemistry, physics, botany, and history. As for experiments carried out on abstemious persons who consumed half a liter of wine, corresponding to two liters of beer, where a retardation in the process of adding up figures, a greater difficulty in learning by heart, etc., appeared for a period of 12 to 24 or even 48 hours, I consider these as only significant of the personal state of the subjects and nothing more. These cases are just as interesting as a paradoxical fever produced by the action of quinine, diarrhoea after opium, parotitis in certain lead-workers, cutaneous eruptions after consumption of mushrooms, or syncope after smelling a flower which for other persons has an agreeable odour. In the great majority of cases the cerebral effects of alcohol taken in small doses are so transient and momentary that it is a matter of daily experience that there can be practically no question of any important disadvantage resulting therefrom.

The conclusion to which I arrive is as follows. Prohibition, for instance, as it is compulsorily enforced by law in the United States of America, cannot be defended by recourse to accurate scientific psychological research nor by the testimony of physical disturbances produced by the moderate use of alcohol. In spite of all this abstainers act just as subjectively as certain Christian sects did nearly two thousand years ago, who celebrated Holy Communion with water. They are influenced by individual aversion to or fear of alcohol and its consequences—the same reasons that bring about abstinence from tobacco. There is really objective reason for their abstinence.

Between excess and abstention lies temperance. The efforts made by temperance societies to prevent the abuse of strong spirits have given rise to a flood of propaganda, among it much that is extremely weak in argument. It has been forthcoming from "social hygienists" who know very little of hygiene and still less of the course of the effects of alcohol, and who are far from knowing the conditions of life of the working classes, so that they are not in a position to favour the world with their lucubrations. It is useless to dwell on the well-established reasons for temperance. Temperance is a vital necessity. It should consequently be applied as a law of life to the satisfaction of all man's desires. Temperance excludes the craving, or at least prevents it from reaching morbidity. Therefore writings in favour of alcoholic temperance must excite our sympathy even though we consider that their utility is not in proportion to the trouble and labour expended on them.

Nevertheless, these writings contrast favorably with the conditions created in recent years in America by the prohibition laws, especially by the Volstead Act and the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution, against which, in 1919, President Wilson opposed his veto in vain. At the present day, the manufacture, sale, and transportation of alcoholic beverages, as well as their import and export, are prohibited in the United States of America. Permits are, however, granted to medical men, who are allowed to prescribe whiskey or wine for their patients if they think it necessary. Not more than a pint may be allowed to the same patient within a period of ten days. It is alleged that 45,000 physicians made use of this permission and issued 13,800,000 alcohol permits in a single year. According to reports of the apparently well-established alcohol traffic in the United States in 1925, many former innkeepers and waiters in the character of qualified pharmacists have opened up new pharmacies for the sale of whiskey. The number of pharmacies in New York State increased from 1,565 in the year 1916 to 5,190 in the year 1922, and has since then further increased in proportion. These whiskey-pharmacies sell legitimate wares below their usual price in order to attract customers for their whiskey trade. During my travels in America from ocean to ocean I made many observations and investigations in the "dry States." I came to the conclusion that there exists an enormous amount of anti-alcoholic propaganda of a most unpleasant kind. Compulsory abstinence has reached such a point that those who have not recently observed the state of affairs with their own eyes would hardly believe it possible that the law could be publicly flouted so frequently and openly and with such gay insolence that the ironic question of foreigners, "When are you going to introduce prohibition?" seems perfectly justified.

If, on the other hand, we read the official American reports on the results of prohibition we might believe that a veritable golden age is reigning in that country. According to these reports, general prosperity has increased, savings-bank deposits have been augmented, the output of manual labour is larger and better, accidents are less frequent, business has increased, and purchasing power is greater. More books are bought, more magazines are read, and more milk is drunk. Prostitution has decreased, adultery is less frequent, venereal diseases and suicides are diminishing, infantile mortality is declining, murder, assaults, robberies, thefts and even pocket-picking have diminished by 30 to 80 per cent, as well as arrests for vagrancy and drunkenness. This last, however, showed an increase in 1921 and 1922. The alcohol-psychosis decreased by 50 per cent in certain parts, and the number of deaths due to alcohol diminished in the years 1916 to 1920 by 84 per cent in fourteen large cities, etc. All that is now necessary in this country is for the blessings of prohibition to bring about the realization of the words of Isaias: "The wolf also shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the kid; the calf and the young lion and the fatling together; and a little child shall lead them." If, as a contrast, the statistics of criminality for New York City are examined, assuming that they are accurate, they produce a very different impression by reason of their disproportion with the facts cited on the preceding pages. The number of murders whose perpetrators were for the greater part undiscovered, amounted to 237 in 1921, 262 in 1923, and 333 in 1924. In 1924 there were 7,000 cases of housebreaking before the courts of which only 587 ended with a conviction.

As the use of alcoholic beverages has, for the greater part of mankind, become a vital necessity, the desire to procure alcohol inevitably leads to infringements of the law, fraud, smuggling, etc., especially in the "dry States." This year many persons were incriminated in an affair of this kind in Cleveland.