| - |

Drug Abuse

EUPHORICA: MENTAL SEDATIVES

OPIUM: MORPHIA

Opium and Morphia as Euphorics: Their History, Production, and Effect

The use of opium and its ingredients as a soothing and euphoric remedy has developed into a grave menace to the life of nations. Differing from alcoholism in that it does not betray its victim to others, the opium habit, especially since the war, has taken hold of whole classes of people who were formerly free from it. This abuse has almost become epidemic, and has moved from various States, in their capacity as guardians of the public health, to take measures of defence against it. Germany is no better than any other country in this respect, for there is nothing which man can do for good or ill which is not common to all nations.

The discussion of these problems necessitates a wider knowledge than the man in the street possesses. The contents of the following pages are derived from my personal researches in narcotics and other drugs of the same kind, and my observations of many persons who had become slaves to this passion both on the coasts of the Pacific and in Europe.

By this passion I mean the state which induces persons, habitually and as the result of a violent craving, to employ opium, morphia, and other substances of the same kind, without being driven thereto by a grave or incurable disease, but with the sole object of obtaining agreeable sensations in the brain, even though they know, or ought to know, that they are risking health and life as the price of this abuse.

This definition distinguishes between those who make use of the drug because of chronic incurable disease, and the morpinist in the usual sense of the word, a sense bearing a certain reproach; but it includes those who become ill through their use of the drug.

In contradistinction from the morally degenerative passsions, such as gambling, the passion for drugs has an actual material basis—namely, the substance in question, which affects the functions of the brain. Of all the consequences which may be inferred, one is decisive: the loss of the will to resist the attraction of morphia, cocaine, etc. The effects which these substances call forth are so agreeable that moral resistance is overcome. The question whether morphia and similar drugs, by momentarily reinforcing the activity of the brain, enable the individual to meet more satisfactorily the increasing demands of the world of to-day and to succeed in the struggle for existence, must be answered in the negative. The substances which temporarily produce these effects are of another species; they are excitants which act on the brain in another way.

Opium and morphia occupy a singular and unparalleled position among medicinal substances, and the little we know of their history, very incomplete as it is, is no less extraordinary. The documents that would supply these gaps are lacking, but our present knowledge of the pharmacology and toxicology of these substances furnishes us with inductive elements of relationship and enables us to reconstruct their history completely.

Relics from the obscure period of the Stone Age, the epoch of the lake-dwellers of some 4,000 years ago, are from time to time discovered. For instance, in the Swiss lakes not only seeds but also capsules of poppies have been found. The examination of these capsules suggests the conclusion that they came not from the primitive form of the poppy, papaver setigerum, but were obtained by cultivation. It is impossible to decide whether the cultivation was brought about in order to obtain the oil of the seeds or merely the narcotic juice of the capsules. But the second alternative is to be considered. We cannot reject it, since a knowledge of the narcotic effect of the juice of the poppy might easily be acquired while cultivating the plant, for instance as a result of tasting from curiousity the juice flowing from an accidental incision in the capsule. The further step to its use as an anodyne is not a very long one. But in that case the inhabitants of the Swiss lakes would indeed occupy a singular position among the lake-dwellers.

Sounder and more conclusive material for the study of the knowledge and use of opium in antiquity may be found in very ancient documents, for instance in Homer. In his time the use of nepenthes, the drug of forgetfulness, was already so well known that the first discovery of the effects of opium must probably be dated back to a very much earlier age. For nepenthes was a preparation of opium, although other interpretations have been given by persons unacquainted with the decisive effects of opium, among others by philologists.

It is stated in the Odyssey that when Telemachus visited Menelaus in Sparta, the remembrance of Ulysses and other warriors acted very depressingly on the assembly. Menelaus then ordered a banquet to be served, and Helen prepared a peculiar drink.

And Helen, daughter of Zeus, poured into the wine they were drinking a drug, nepenthes, which gave forgetfulness of evil. Those who had drunk of this mixture did not shed a tear the whole day long, even though their mother or father were dead, even though a brother or a beloved son had been killed before their eyes by weapons of the enemy. And the daughter of Zeus possessed this wonderful substance which Polydamna had given to her, the wife of Thos in Egypt, that fertile country which produced so many balms, some beneficial and some deadly.

There is only one substance in the world capable of acting this way, and that is opium, the vehicle of morphia. Its characteristic effect, especially after habitual use, is precisely such a state of indifference towards everything except the ego. The execellent description of this state which Homer gives is apparently the result of observing opium-eaters, i.e. people who habitually use opium for their pleasure. For the first dose as a rule does not produce these effects on the emotional life, and even if produced, they would not be of such long duration. It is not poetic licence, but observation from real life, when the poet says that those who were under the permanent influence of opium were free from emotions of the soul the whole day.

The description enables us to make another assumption, that warriors consumed nepenthes before battle in order to dull their senses of danger, for Homer here speaks only of the numbing of the soul towards the horrors of combat. This might have happened, and in my opinion did happen, before Troy and elsewhere. A connection is thus established with the employment of opium for the same purpose hundreds and thousands of years later. Only the initiated, the "heroes," made use of it. Indeed, this substance and the knowledge of its action was not accessible to everybody. Surely Helen had prepared this opiate at other times and on other occasions for her confidants. It was the Egyptian Polydamna who procured it and from whom she learnt its use. This is an important indication of the country which first produced poppies.'

In the papyrus of Ebers we find a chapter with the title "Remedy to prevent the excessive crying of children." It will be seen that for this purpose gpenn is used: "gpenn, the grains of the gpenn plant, with the excretions of flies found on the wall, strained to a pulp, passed through a sieve and administered on four successive days. The crying will stop at once." The theory that the action is based on opium is well founded. Either the unripe seeds—the ripe ones are useless—or the capsule of the poppy were employed. To-day, both in Egypt and Europe, children are still "soothed" with the aid of this product, and not infrequently the effects are fatal.

The cultivation of opium, then, probably spread over Asia Minor, which land is called to-day, though without proof, the cradle of opium. From there the poppy reached Rome, Greece, and other parts. In Egypt, as in India, the right of prescribing and supplying opium must have been in primitive times, as a piece of occult knowledge, a privilege of the priests. Many obscure events of history can be unraveled by the light we receive from the fact that the action of opium was known. At the beginning these very powerful medicines were used for philanthropic purposes, and later they often served political or personal ends and the designs of passion and vengeance.' Representations of poppies were often engraved on Roman coins of the later ages. In Jewish history they have only been found on the bronze coins of John Hyrcanus, prince and high-priest of the race of the Maccabees (135-106 B.C.)

The seductive power of opium, which incites an incessant renewal of its use, as millions of experiences and human nature itself prove, found its victims in Rome and in Greece, who desired a state of mental detachment from the life of the world. The short descriptions which are given to us by the naturalists Theophrastus (third century B.c.), Pliny, and Dioscorides (first century A.D.) show that the toxic effects of the drug which were judged so important that Diagoras of Melos and Erasistratus, in the fifth and third centuries before Christ, recommended the complete avoidance of its use. But the employment of

Lethaeo perfusa papavera somno

"poppies soaked with sleep of Lethe," has never been abandoned. Not only the dragon which dwelt in and protected the garden of the Hesperides, lying in the far-off country of the Moors, where the sunsets and the huge mountain Atlas bears the heavens on his shoulders, succumbed to its action:

Spargens humida melle soporiferumque papaver

. . . "gave him inebriating poppy with dewy honey," but also innumerable human beings.

It is interesting to note that the poppy-head belonged to the mysteries of Ceres, for she took papaver "to forget the pain," ad oblivionem doloris . That is why a small earthen statue of Ceres-Isis with a torch holds poppy-heads in her hand.' Everywhere in antique art we meet with the poppy as a mythological symbol of sleep, and even a personification of the dispenser of sleep, the god who gives sleep, the fmtvo86 g; he is presented as a bearded man leaning over the sleeper and pouring on his eyelids the poppy-juice contained in a vessel of horn which he holds in his hand.

On the coffin of the sleeping Ariadne, the bearded God of Sleep is holding poppy-heads and an opium-horn in his hand. At a later date the God of Sleep, Somnus, is depicted as a young genie carrying poppies and an opium-horn, or with a poppy-stalk in his hand.

In order to keep Hannibal away from Rome and to overpower him with dreams, Juno cries:

Per tenebras portas medicata papavera cornu . . .quatit inde soporas

Devexo capiti pennas, oculisque quietem

Irrorat tangens Lethaea tempora virga.6

Night and Sleep live both in the same dwelling, which, according to Lucian's romantic picture, is surrounded by a plantation of poppies. They appear with the sinking sun with a wreath of poppies round their heads, followed by a flock of dreams, and pour on man the soporific poppy-juice which binds his limbs.

The eating of opium, which has been practised here and there ever since the discovery of its effects, increased in proportion to the wider knowledge of the beneficial properties of the substance. How could it be otherwise? Ceasing to be the exclusive property of a minority, it lost its mystery and became a common object of commerce. It exercised its attraction of necessity, leading people to a first trial and consequently to the first step towards the habit. Time has preserved some testimonies of this abuse, which in all periods has shunned the light. It is stated, for example, in the second century, that Lysis took four drachms of poppy-juice without being incommoded.' He must have been an inveterate opium-eater; such toleration would otherwise have been impossible. In a period of the great Arabic doctors of the tenth—thirteenth centuries, and in consequence of the warlike expeditions of the Mohammedans, the passion for opium was propagated from Asia Minor to almost every part of the world. The considerable successes of Paracelsus, the miraculous cures which he effected with the aid of opium at the beginning of the sixteenth century, no doubt produced many opium-eaters; perhaps even Paracelsus himself took opium. "I posses a secret remedy which I call laudanum and which is superior to all other heroic remedies." His later life and way of acting create the impression of an opium-eater. I think it is very near the truth; I have seen many morphinists whose behaviour was similar.

In the year 1546, a French naturalist, Belon, who had travelled through Asia Minor and Egypt, drew attention to the great development of the abuse of opium among the Turks. "There is no Turk who would not buy opium with his last penny; he carries it on him in war and in peace. They eat opium because they think that they thus become more daring and have less fear of the dangers of war. In war-time such quantities are purchased that it is difficult to find any left." Belon saw an opium-eater take 2 gr. in one dose, and when he gave him 4 gr., accurately weighed, he consumed these at once without inconvenience. At this period opium was already exported on a large scale to Persia, India, and Europe. Belon reports that at that time fifty camels laden with opium proceeded to the two former regions. Whatever the motive for its use, the Portuguese botanist Garcias ab Horto, at the beginning of the sixteenth century, mentions the suppression of disagreeable physical and mental impressions experienced by the Indian opium-eaters whose acquaintance he made at Goa, and he even observed that when they had taken a sufficient quantity "They spoke wisely about all sorts of things. Such is the power of habit."

The importation of this substance into Europe from the East increased the numbers of those who used it, and, while probably taken in the first place as a medicine, it never ceased to hold its victims captive. I have found publications from the sixteenth—eighteenth centuries according to which persons had been medically observed in Germany who were "addicted to opium-eating" and consumed up to 40 gr. a day, and only showed signs of "lassitude and sleepiness." Some of these are reported to have continued the consumption of opium in increasing doses for a number of years, one woman, for example, taking in forty years 63 pounds of "fluid opium," i.e. tincture of opium. Another consumed 4 gr. a day for nineteen years, 27 kilos in all. A third, led to use it as an anodyne by an accident, is said to have introduced 100 kilos of the drug into his system in the course of thirty-four years.

Prosper Alphini at the end of the sixteenth century reports that some Egyptians consumed 12 gr. of opium a day without inconvenience.' Later, in the seventeenth century, for instance, medical men such as Sydenham enthusiastically propagated opium by recommendation and this not only against painful diseases. Eventually opium was considered as the "Hand of God," or the "Sacred anchor of life."

Save for some medical reports, we have only a few personal observations originating from the multitude who in the following centuries became slaves to opium and succumbed to it. One of these is by an English writer, De Quincey.9 At the age of seventeen he began taking tincture of opium against neuralgic pains. For eight years he experienced no harm, and then entered a stage where the "Divine Poppy-juice became as indispensable as breathing," and took a glassful every day mixed with port wine and water. Renewed physical suffering made him "a confirmed opium-eater." After another eight years he daily consumed 8,000 drops, about 20 gr., of the tincture. In one of the following years which was "a year of brilliant water set and insulated in the gloomy umbrage of opium" he managed to diminish the daily dose to one-eighth. This was for a long time the last glimpse of the light in his life, which he spent under this magic spell. In spite of a fresh increase in the doses administered, he thought he was indebted to opium for his times of happiness—until the miseries and tortures of opium began.

This misery all such must experience. They have sold themselves body and soul. The proceeds of the sale are rapidly squandered in the delights of opium. These delights are inexorably followed by a state of individual physical and mental torture, of remorse mingled with grief.

This the English poet Coleridge discovered, who on some days consumed 20 to 25 gr. of tincture of opium. The same lot befell Francis Thompson, one of the most gifted younger English poets.

It is well known also that some medical men have been addicted to opium. It was known even in those times that habitual opium-eaters could not be deceived when their opium was replaced by other substances because, like the morphinists of to-day, they thereby experienced "unbearable pains."

So early as the eighth century the Arabs brought opium and the knowledge of its effects, by way of Persia, to India and China—to China which represents numerically a quarter of the earth's population. Before the Tang dynasty it was unknown. In the year 973 it was officially mentioned in the medical book K'ai-pao-pen-tstio under the name of ying-tzii-su, and at the same time we find a poppy beverage recommended in a poem of Su Tung-P'a which gives us the impression that it alludes to other and more agreeable effects than the cure of dysentery, etc. At the beginning of the twelfth century cakes of opium were prepared from the dried milky juice of the poppy in the form of a fish, certainly not for medicinal purposes alone. In the latter part of the fifteenth century there existed in China an important traffic in opium, both imported and home produced. Towards the end of the Ming dynasty—the last Ming emperor reigned from 1628 to 1644—when the smoking of tobacco was prohibited, the practice of smoking opium made its appearance. Later this was modified, as an ambassador sent to China in 1793 reports, and the habit of smoking tobacco mixed with a small amount of opium was established. When in 1729 two hundred chests of opium were imported, chiefly by the Portuguese from Goa, the emperor Yung Ching strictly prohibited the sale and smoking of opium. In 1790 the annual report reached 4,000 chests, 16,000 in 1830, more than 25,000 in 1838, and 70,000 in 1858. The consumption of opium rapidly increased to considerable proportions, together with the smuggling of opium, against which new measures were taken in 1820. The last prohibition of the import of opium into China dates from that year. The English, thinking this detrimental to their commerce, the Opium War broke out, beginning by the destruction, on the part of the Chinese, of 20,000 chests of opium, and continuing from 1834 to 1842. The Chinese had finally to purchase peace at the cost of considerable losses in money and territory. Fifteen years later a second war broke out which likewise ended unsuccessfully for China. The Treaty of Tientsin legalized the Chinese opium traffic.m In this dire necessity China decided to cultivate the poppy herself. Large tracts of land were devoted to this purpose, at the expense of the cultivation of foodstuffs. In the meantime the passion for opium-smoking had seized on large sections of the population, and was probably augmented by the increased facility for obtaining the drug in the country itself.

A further change took place in 1906. After a century of demoralization through opium, China decided to give up the cultivation of the poppy. According to a convention with England, poppy-growing was to be gradually diminished during a period of ten years, while England was to reduce her opium imports into China at a corresponding rate. The year 1917 marked the end of this agreement, which shows some degree of success. The cultivation of opium ceased in one province after another and the English imports were officially discontinued. But unfortunately, China has no means of controlling the traffic in the foreign concessions, for instance Shanghai, Hong-Kong, and Macao. Here and in other places the Chinese can procure opium and even resell it. Opium for smoking is prepared in Macao. As it is impossible under existing circumstances to introduce it openly into China, it can only be distributed as contraband. Naturally a large quantity is consumed in the town itself in the notorious opium dens where, as I have seen in other places, those possessed with the opium demon lie on the bunks placed one above the other, like the bread-shelves in a bakery, and taste the greatest joy of their earthly lives.

If it is asked what becomes of the large amount of opium produced in British India, for instance in Patna, Malwa, Benares, we may consider it more than probable that it reaches China by indirect routes.

This opium, produced in the United Provinces, is Monopoly-Opium. The whole yield must be delivered to a Government agent at a fixed price. It is then sent to the State factory at Ghazipur to be rendered suitable for the market. Every month auctions of this substance take place at Calcutta. The product obtained in the native states of Rajputana and Central India, which is subject to duty on entering the British area, realizes the same price as English opium.

Recent information" shows that during the last few years large amounts of Indian opium of enormous value have been accumulating at the free ports outside the naval customs barrier. In the year 1912 the value of opium deposited at Shanghai alone was estimated at £11,000,000 sterling. According to the agreement it cannot be imported into China until there is proof that opium is being cultivated in China itself. The great efforts which China has made in order to obtain her deliverance from opium have caused millet and cotton to spring up even in the most distant corners of the empire, where formerly stretched many-coloured fields of poppies. This beneficial policy seems now to be meeting with certain obstacles. The savage tribes of Eastern Tibet, although for the greater part independent, are nevertheless included in the Chinese territory according to the terms of the opium convention. In the solitude of isolated and inaccessible mountains far from the world, in places to which Chinese authority and its agents penetrate rarely and with difficulty, these tribes cultivate the poppy and introduce its juice surreptitiously into China. It is remarkable that the Chinese were unable to impart the passion for opium to the aborigines in Central Tibet to any greater extent.

Latterly Japan has been the greatest buyer of opium in Calcutta.'2 The merchandise arrives at Kobe and is thence conveyed to Tsingtao. Very considerable quantities of morphia are said to be manufactured in Japan, which are sold in Manchuria by Japanese merchants bearing Formosa passports. From Tsingtao it is conveyed via the provinces of Shantung, Nganhwei, and Kiangsu; from Formosa, together with opium, to Fokien and Kwang-tung. In this way China is deliberately overrun from this side with these two products. The total quantity is estimated at 20 tons a year. An injection of morphia costs 3 to 4 cents.

The export of morphia to the Far East from England increased up to 1914 (see Table 1).

| YEAR | AMOUNT OF MORPHIA EXPORTED |

| 1911 | 5 1/2 tons |

| 1912 |

7 1/2 |

| 1913 | 11 1/4 tons |

| 1914 | 14 tons |

According to information from Japanese sources the export of morphia from England fell from 600,229 ounces in 1917 to a quarter of this amount in 1918; this is to be explained by the manufacture of this product in Japan itself.

What this new "morphia-phase" in the history of opium means for the population of the Far East, if, as is certain, morphia should continue its triumphant march, can be gathered from our experience of this drug in Europe. It is already reported that there were numerous victims of morphinism in the years 1914 and 1915.

It is related that years ago an old opium smoker earnestly desired to be broken of the unfortunate habit. He offered a large reward for a cure. One of his compatriots, who had learnt the use of morphia from a foreign physician, offered to cure him, and treated him with injections of morphia. The sensations which the opium-smoker experienced were so agreeable that he very soon abandoned his opium-pipe. The quack went to Hong-Kong and proclaimed that he possessed an unfailing remedy for the opium habit. In a short time the number of his clients increased to such an extent that he erected a whole series of institutions for the injection of morphia. At last there were about twenty in existence. Finally the government ordered the closing of these establishments for human destruction and prohibited the supply of morphia without a doctor's prescription. Now this evil continues to develop clandestinely.

Such Indian opium as does not reach China by a direct route seeks for other markets, and reaches Chinese merchants and consumers through indirect channels. Those Chinese territories which are in foreign possession import particularly large quantities of opium. In the foreign quarters of Shanghai the number of opium shops increased from 131 in 1908 to 663 in 1916. The inhabitants of the Chinese quarter can obtain any amount from these shops. The situation is the same in Hong-Kong, Kowloon, and Liangtua.

Next to India, Turkey and Persia are the greatest producers of opium in the world. A large part of the Persian opium, called in its pure state Shire-Teriak, but when adulterated for export and consumption Teriak-i-Chume and Teriak-i-Jule, goes to Hong-Kong and Formosa and from there probably to China also. This is probably the reason why it is not included in the following table of the countries of origin of opium. Opium is cultivated through Persia. The best qualities are supplied, among other places, by Isaphan and Shiraz—also famous on account of its wine—Shiraz, the valley of roses and nightingales, which shelters the tombs of the poets Hafiz and Saadi. Isaphan is the center of the opium trade. So long as forty years ago 2,000 boxes of opium, representing a value of about £,150,000, were exported from Bushire to England.

Large quantities of opium are now produced also in Macedonia, Bulgaria, and Yugoslavia. The last-named country before the war produced annually an average of about 120,000 kilos. It has lately increased to 150,000 kilos, representing a value of 200 million dinars.

In Egypt the cultivation of opium is prohibited.

Other countries also import considerable quantities, for instance, Cochin-China, which imported in 1912-13 840 chests of opium each of 140 pounds, in 1914-15 2,690, and in 1916-17 3,440 chests.

In Saigon crude opium, which is a State monopoly, is refined into smoking opium, or chandu. Already twenty years ago 67,000 kilos of crude opium were annually refined to 44,800 kilos of chandu. The annual consumption of opium, without counting contraband, is estimated at 120,000 kilos. The smokers were mainly the Chinese living in centers such as Saigon or Cholon. Considerable quantities are delivered to distant parts. The small island of Mauritius, for instance, imported in 1912-13 only ten chests, but in 1916-17 as many as 120.

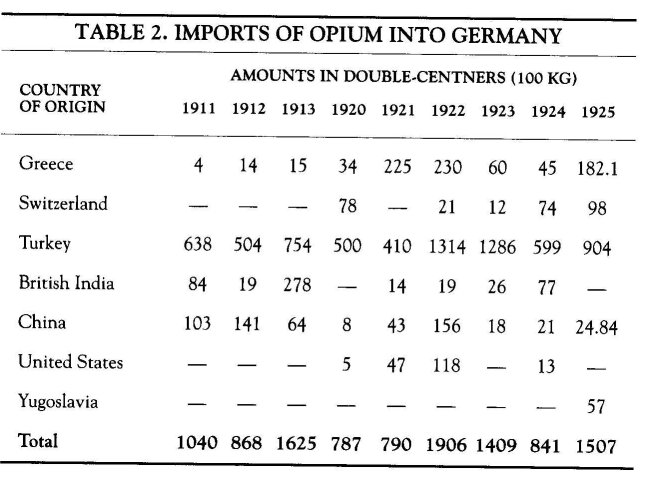

Table 2 illustrates Germany's position with regard to opium, and also shows the countries of origin of the drug.

The Consumption of Opium and Morphia at the Present Day

An alarming spectacle is presented to the observer who undertakes to describe the extension of the passion for opium and morphia from a scientific point of view. Morphia, a scourge of recent date, has established itself all over the world. It is always ready for use, and can be taken simply and conveniently without any elaborate apparatus: a syringe, a small flask, and a dark corner is all that is needed. The arm or thigh can be pierced with the needle through the clothes; no odour reveals the dope victim, as in the case of opium, no drowsiness to necessitate lying in a horizontal position—the absorption of the morphia solution in the subcutaneous tissues has the power to transform the individual who was tortured by abstinence and unable to work into a hero ready to cope with the exigencies of modern life. The time will come—if no miracle happens—when the more recent drug, morphia, will have at least unthroned if not vanquished its ancient and clumsy rival, opium. Nevertheless, there will always be some who seek a life of dreams and visions, such as the smoking of opium produces, who will prefer the latter drug because its effects are more attractive and alluring than the cold action of morphia. That is why even in our days isolated devotees of opium are to be found all over Europe. It is not long since the discovery that the drug was taken in Paris in certain places by women, even young girls. Just before the war the Chamber of Deputies and French public opinion were stirred by the revelation that in the French navy and particularly in the naval ports in the Mediterranean opium-smoking had developed to a degree dangerous to the whole nation. A part of the opium was said to originate from the State factories in Indo-China; the rest was of European origin.

There are other countries in Europe where decrepit and degenerate habitués of both sexes, men and women of the demi-monde, victims of a violent and blind craving for sensation, are addicted to smoking opium. The farther east we go, the larger the number of opium maniacs. The opium habit obtains in the Balkans and increases as we approach Asia Minor. In some places, for instance in Damascus, it is clandestinely indulged in, but as an acknowledged drug it has permeated all social ranks. Of the three Iranian countries, Baluchistan, Afghanistan, and Persia, the last-named occupies an important rank among opium-consuming lands. In the northern provinces, particularly in Khorasan, both Mohammedans and non-Mohammedans smoke a great deal of opium. Bokhara and Afghanistan consume only a small amount. But many a heavy consignment has doubtless crossed the Hindu-kush and the frozen passes leading to Eastern Turkestan. Here, for instance in Kashgar, men and women avidly smoke opium in publicly recognized opium dens.

Farther south, towards India, the passion for opium increases. In the states of Rajputana the hardiest native races, the Rajputs and Sikhs, smoke opium, and the Hindus also are addicted to this vice. On the coast of Coromandel all social classes make use of the opium pipe, the Hookah. A mixture of opium and rose-leaves is smoked with a little tobacco. There are also opium eaters, for instance in Bengal. Some years ago the number of opium addicts in Hyderabad, out of a population of eleven million, was estimated at over one million, including 12 per cent Mohammedans, 7 per cent Hindus, and 5 per cent Pariahs, people from the towns and the plains as well as from the highlands. Opium-eating is taboo among some religious sects, e.g. the Yeragis in Eastern Bengal. The ratio of men to women among the opium-eaters of India is approximately 73:27. They are for the most part thirty to forty years of age.

In the territories of Rajputana, Central India, and the province of Gujarat during festivals a 5 per cent solution of opium is used, called amalpani or kusamba. The smoking of opium is practiced almost exclusively in the cities. Extracts of opium are used under the names of maddak and chandu, the latter being an extremely concentrated extract which is consumed after a maturation process lasting twelve months under the influence of aspergillus niger.

The chain of opium-using countries continues to the south of the Himalayas as far as the territory around the Brahmaputra. In Assam the natives have given themselves up completely to opium. The Kachari are so passionately addicted to it that they demand to be paid in opium instead of money. Both men and women among the Kakhyens, Karens, and Lapais, the inhabitants of the Kasi mountains, smoke opium. They can cultivate only very small quantities on account of the height of the mountains, and they obtain the greater part from China. The savage Tunings and Nagas descend from their hills into the valleys in order to barter ivory, cotton, etc., for rice and opium. The craving for the drug increases eastwards towards the China Sea, and both here and in the Pacific Ocean takes the form of a vital necessity. Certain tribes of Burma, the Pa-yii and the Kachin, smoke opium as their principal occupation. The powerful force of imitation does not spare Siam. In spite of the severest penalties, opium has forced its way via Mekong to Tonkin, Annam, Cambodia, and Cochin-China. The Tonkinese smoke less than the Cochinese, especially the upper classes. Among these, as among the Annamese, who are reputed to be hysterical as a result of opium, a moderate smoker consumes 60 to 80, a heavy smoker up to 150 pipes a day.

An extensive contraband trade in Chinese opium also exists in these parts. It is cheaper than that supplied by the local French agents in Saigon, Hanoi, etc., and unfortunately many Europeans are to be found among the buyers.

The most diverse physical disturbances afflict the opium-smoker; among others, peculiar inflammations of the mouth, stomach disorders and disturbances of the circulatory system, heart diseases, weakness of the limbs resembling paralysis, and occasionally also disturbances of the bladder. With respect to the activity of the brain the same disorders can be observed with which morphinists are afflicted.

We now come to the country where the consumption of opium is greatest—China. This is also the centre from which Chinese emigrants have carried the opium vice with them throughout the world. Far away from their home country the Chinese have transported this habit; along the Manchurian railway, deep in the immense forests, only accessible by narrow paths, small farms for the cultivation of poppies can be found. The opium from these is secretly sold in the towns, particularly in Harbin.

Wherever the opium habitué turns his steps, the drug accompanies him. It follows him into civilization, to America, Canada, Vancouver Island, Alaska, Africa, Australia.

In China itself opium is smoked to an excessive degree. There is hardly a province which is an exception to this rule. In Chinese Turkestan the Shantu are addicted to opium. In Kan-Su, in the southern Kulu-nor country, it has been estimated that 80 per cent of the population of the towns and 30 to 40 per cent in the villages smoke the drug, and that their approximate monthly ration is from 150 to 200 gr. per head. Tafel on his expedition through Tibet encountered hardly anyone who did not smoke opium. Yunnan and Szechwan are the provinces whose population suffers most from this scourge. The missionaries of Kiang-Si complain of the smoking of opium, and especially of the eating of the drug by women, this latter being tantamount to suicide. Throughout the vast territories of the Chinese empire the traveller may witness the disastrous effects which opium has exercised and will continue to exercise on mankind.

The drug has forced its way into Mongolia. Prshevalsky, who explored China with remarkable success fifty years ago and predicted the disastrous effects the opium plague would have for China, found this drug also in Ala-Shan. The passion for its reigns also in Formosa. Even the chewing of betel by the savage Chinwan has been replaced by the opium habit. In Japan, however, the drug seems to have lost its sway.

Seventy thousand Chinese live in the Philippines, the greater part of them opiomaniacs. Many of the natives are addicted to the vice, which the Spaniards attempted to abolish by a State monopoly of opium. America seeks to remedy the evil by severe punishment, treatment centres, and instruction. But she is unable to prevent the consumption in the homeland.

The use of opium forced its way irresistibly into the Dutch Archipelago, to Java and Sumatra, where the natives of Batavia are passionately addicted to the drug and have attacks of delirium if their supply is suddenly stopped. It reached Nias, the islands of the Banda Sea, the eastern Moluccas and Western New Guinea, the Am and Key Islands, Ceram and Borneo, where it is not only smoked by the savage Dyaks but also by the Chinese. The trade is a monopoly in the islands of Oceania, as it is also in other parts of the world. Agencies for the sale of the drug are established in the smallest village.

The opium vice of the Chinese has found its way even to the fifth continent, Australia, where it was introduced side by side with alcohol. The Chinese, however, did not derive the main profit therefrom, but they left this to the Europeans. Alcoholism, and still more the smoking of opium, which the natives very rapidly copied from the whites and Chinese, has inspired them with a fatal inclination for "dope" and brought about a remarkable reduction in their numbers. In their camps in Queensland and other parts we can observe the decrepitude and the feeble aspect of the Maoris, formerly a very robust race. For the most part imported opium is employed. Attempts at cultivation have revealed a product of a remarkable quality.

The South Sea islands have also fallen under the spell of opium, that triumphant poison. It remains wherever it has sunk its roots. We have information about conditions on certain of these islands, e.g. the Gilbert and Marquesas Islands. The Chinese brought with them the taste for opium which unfortunately supplanted the harmless kava which had until then been in use. The natives of the Marquesas Islands buy the opium from an agent-general of the French State monopoly, who at the end of the last century was only allowed to sell it to the Chinese.

The opium habit has taken root in those parts of Africa in which poppies are cultivated. This is the case in Egypt, for instance, where its degenerating influence on the lower classes was pointed out many years ago. In Tunis and in the towns along the west part of the north coast of Africa opium is only smoked clandestinely and to a very small extent. In the Tripolitan town of Mursuk more users of the drug can be found. In Arabia the smoking of opium has developed hardly at all. In Mecca there is a street named "Kashkarshia,"13 i.e. street of the opium-sellers.

The customers descend into a kind of empty cellar wherein ledges for sitting are provided along the wall. Men can be found there with a pale and bloodless appearance in spite of their brown skin. Everyone has a small pipe in his hand and inhales the smoke of the glowing opium, which is condensed on the moist mucous membrane of the respiratory passages. All the smokers are silent. From time to time one or another of them ejaculates "0 Allah," or "0 divine goodness!" In East and Central Africa, for instance near Mazaro on the banks of the Kwakwa in Mozambique, the Hindus from Malwa organized poppy cultivation several years ago. The use of opium, however, in that region is not considerable. Not many Arabs have been brought by the Hindus to the smoking of opium. In other parts, for instance in East Africa, in Uganda, or on the banks of the Congo, only the Chinese workmen smoke.

The extension of the use of opium in the United States of America is of very great interest, especially on account of the war declared by the legislature in that country against alcohol. Reports published over thirty years ago tell of the increase of the use of opium in some districts, for instance Albany. Whereas the population increased by 59 per cent, the consumption of opium increased by 900 per cent, and that of morphia by 1,100 per cent. It was generally alleged that the largest increase took place in the prohibition states. Recent statistics disclose facts which testify only too clearly to the alarming growth of this evil.

According to statements made by the Chief Medical Officer of New York City in 1921, the Americans consume twelve times as much opium as any other people in the world. More than 750,000 pounds are imported annually into the States, that is, 2.5 gr. per head of the population. The amount of opium used for legitimate purposes does not amount to more than 70,000 pounds a year. The report of a physician of the great New York State prison proves the increase of opiomania in the capital. The number of persons convicted of illegal consumption of opium increased by 789 per cent in the years 1918 to 1921. I do not establish any relationship between these figure, which I do not question, and the prohibition of alcohol. There are many opinions on the prohibitionist side which partly dispute the increase in the number of drug-takers, or, if it must be conceded, give other reasons for it.

What I have outlined above proves emphatically that neither the world's broadest oceans not its highest mountains can serve as a defence against opium and morphia, those drugs which enslave the human brain, enervate the mind, and force the body to follow vices which are fatal to its existence.

An attempt to remedy this calamity is almost certainly doomed to failure. Even if the smoking-dens of the Far East were completely abolished, it would not be possible to suppress the vice in the home. And what is more unfortunate, morphia and the morphia syringe will always be employed.

What is taking place in the Far East, where the injection of morphia is replacing the opium pipe, clearly shows that if it was impossible to suppress the old evil it will be all the more impossible to control the new vice which is developing. This is all the more true, perhaps, because the distribution of the drug by traders cannot be effectively checked. In the Spring of this year some merchants were prosecuted in Hamburg for having diverted to China about 50 kilos of morphia after a permit had been issued for their export to Turkey.

There are also many curious means employed in Germany for inducing people to the consumption of opium. In 1918 it was officially stated in Wurtemberg that the use of the stalks and capsules of poppies was being openly recommended as a substitute for tobacco, and that these were in consequence purchased for this purpose. The capsules of poppies in a ripe or unripe state contain enough opium to produce the effects of the drug if inhaled as smoke.

Morphinism

Morphia very early commenced its triumphant march in Europe. The span is short that separates its discovery in 1817 from the year 1830, when Balzac, that keen observer of human nature, in his Comedie du liable makes the devil enumerate the reasons why he has no time to seek his personal pleasure. What hinders him is the enormous increase in the population of his kingdom, hell, as a result of the discovery of gunpowder, printing, morphia, etc. At that time, indeed, morphia served mainly as a suicidal agent. Very soon, however, morphiomania supervened. It increased mysteriously to an extent which very few foresaw, and the number of its slaves gradually augmented. The great wars of the epoch, the Crimean War and its successors, contributed to its development. Not long after I had reported a case of morphinism in a ward attendant in 1874, the first curative treatment was undertaken. The extension of the evil, which until then had been hidden, became apparent.

The causes of its development were and are those I have already indicated:

(1) The impossibility of breaking away from the morphia habit after it has served as an anodyne and anaesthetic. The sensation of extreme well-being experienced on such an occasion enslaves the person to its further use, although the initial cause has disappeared.

(2) The desire to be freed from a state of depression or mental excitement.

(3) Curiosity and the instinct of imitation, soon leading to the pure and simple desire for a euphoric state which in due time makes the individual a slave to the drug. Among medical men the idea existed for a long time that they could not become addicted to the drug. Experience has proved the contrary. A large number of doctors are morphinists. A statistical table of addicts, including all countries of the world, gave 40.4 per cent doctors, and 10.0 per cent doctors' wives.

In Paris the number of morphinists was estimated at 50,000, that is, one to every forty inhabitants. At the present day this figure is said to have considerably increased. Many years ago I pointed out that if alcohol ruins the hands of the people, morphia ruins their heads. Actually, during the last few decades and especially after the Great War, morphinism has developed in the former direction also. But medical men, professors, pharmacists, writers, artists, lawyers, officers, high officials etc., still predominate among this class of drug-takers.

The demoniac power of morphia can even be established among animals. I administered the drug to pigeons daily at a certain time. The effect of the injections abated within a few hours and the birds remained in their cages in a state of depression; but as soon as I approached with the syringe they came out, flapping their wings.

A cat was injected daily with morphia during a longer period. After some time it was apathetic before the injections. After treatment this state was reversed. After thirty-four days the animal died from emaciation on account of digestive disorders. The avid desire for opium was also established in the case of a monkey. Very far down in the animal kingdom, in rats, etc., and even in bees, the violent craving for opium or poppies has been observed. In the countries where opium is smoked, cats, dogs, and monkeys inhale the smoke which their master expels from his opium-pipe, and it is said that monkeys consume the opium which oozes from the bamboo pipe.

Infants can also be habituated to opium. A child of four months whom the nurse provided with decoctions of opium capsules in increasing quantities for insomnia, was cheerful when waking from sleep and readily took the bottle. It pined away as soon as withdrawal of the drug was attempted, and the application of the beverage had to be prolonged. After a further two-and-a-half months the child died. Its physical and intellectual development had not made the least progress during this lapse of time. Visual and auditory perceptive faculties were hardly observable; the child recognized nobody and had a fixed stare.

The evil practice, to give it no worse name, of doping children with decoctions of opium or tincture of opium in doses which must necessarily be increased in order to soothe them is widespread and has many victims.

The report of the Royal Commission on Opium, published in several volumes in 1896, contains various misconceptions which are liable to create false impressions. It states, e.g., that the moderate habitual use of opium, which in reality amounts to 0.15-0.8-2.5 gr. per day among 5 to 7 per cent of the population of India, is quite harmless to the well-being of and the health of the people, on account of the power of resistance of the Hindu to this toxic agent. The custom of giving opium to children in order to keep them quiet and to enable the mother to carry on her work undisturbed, a custom which obtains in the states of Rajputana and Malwa and in the Bombay presidency, the report likewise regards as inoffensive. In these countries an initial dose of 3-5 milligrammes is administered in the first weeks or months of the young life, and is gradually increased to 15-30 milligrammes, and even to 0.12 gr. once or twice a day. In Bombay "Pills for Children" (Bala-Golis) are sold which contain 0.01-0.02 gr. of opium. After the children have reached the age of two to five years they are weaned from opium. How this is done is not described. Deaths from excessive doses do not occur among Indian children, but "only" sometimes dysentery, whereas European children treated in the same way by their nurses are apt to die. In these reports the facts are correct but the conclusions are wrong.

Morphinistic mothers bear morphinistic children who are restless and excitable, and can only be soothed by opium. Suckling with the milk of a morphinistic mother is liable to produce a drug habit in the child, because the morphia passes into the milk.

Family morphinism is particularly tragic, the wife and even the children being lured to the drug-habit by the father. It is impossible to explain the psychological impulse which leads the original drug victim to commit such an act. If mental disease were not taken into consideration it would constitute a crime according to our moral code. For every morphinist knows or will learn that his passion will compel him to follow a path of misery to the bitter end. If it were not for his intellectual disturbance he would, by offering a chronic poison to others, be knowingly thrusting them into disaster. The fact that this takes place with the victims' consent does not mitigate the offence.

The possibility of keeping up an appearance of normality and of continuing to lead within certain limits an ordinary life, exists, as I have already stated, by the gradual increase of the doses of the drug as demanded by the cells of the individual brain. The daily consumption, which at the beginning was a few centigrams, may increase to 4 to 5 gr. Even in the case of infants it is necessary to augment the initial dose. A child of seven months with hydrocephalus received 0.2 milligramme a day. The dose had to be increased to 0.6 gr., which after eight and a half months occasioned death.

The ever-menacing and perpetually increasing internal lassitude of the brain, incessantly roused by the drug to a certain degree of activity, finally gains the victory. The last very large doses of morphia have toxic effects only, and scarcely permit their normal activity to the brain and the organs under its direction. The extent of time occupied by this process varies with the individual, i.e. according to his internal powers of resistance. Every prognosis may collapse before the varying and incalculable possibilities of the vital activity of an individual life.

We are entirely cut off from all knowledge of the internal process which takes place during the use of morphia. We can only perceive the phenomena. It is in vain that we ask for an explanation. It is a subject on which meditation is fruitless and always ends in an admission of our inability to comprehend it. Psychology has so far avoided investigation in the field of the abnormal mental activity produced by the use of narcotics, except in the case of anhalonium lewinii. It is more than doubtful whether the most exhaustive analytical experiments will ever produce positive results. It will, in my opinion, never be ascertained why the brain-cells exhibit such a violent craving for morphia (which in the case of alcohol is less apparent) and why the strongest resolution of the morphinist fades to nothing before the imperative demand of the brain-cells.

The Observable Internal Process in Morphinists and Opiumists

The effects of the prolonged use of morphia unfold themselves in several stages which cannot be accurately separated but have each their particular character. The beginning of the process finds the morphinist in a state of delusion with regard to the value of his faculties, his work, and his agreeable sensations. The ego bases itself on a false valuation with respect to the personality itself and the rest of the world. But whatever be the cause of this psychological change, the individual himself perceives it, work seems to progress more favorably, the small buffets that life dispenses are not felt as such, and this increased vitality lasting six to eight hours is the result of one dose of morphia.

This introductory, seductive stage, which may extend over a period of months, is succeeded on increasing the dose by the more delicious second morphinistic period, filled with a feeling of well-being, absolute contentment, free from desire, undisturbed mental calm.

An opium-eater who arrived at this stage has expressed his sensations in an emphatic style which we must consider as corresponding to his real impressions: "0 just, subtle, and all-conquering opium! that, to the hearts of rich and poor alike, for the wounds that will never heal, and for the pangs of grief that 'tempt the spirit to rebel,' bringest an assuaging balm . . . thou buildest upon the bosom of darkness, out of the fantastic imagery of the brain, cities and temples, beyond the art of Phidias and Praxiteles . . . and 'from the anarchy of dreaming sleep' callest into sunny light the faces of long-buried beauties ... Thou only givest these gifts to man; and thou hast the keys of Paradise."

The flood of the obstacles of life breaks on the morphinized brain without leaving any impression or trace. No disagreeable mental state is felt as a discomfort; care or sorrow hardly touch the soul. Lighter emotion such as worry and indignation evaporate without making any impression at all. Freed from everything which ties man to earth, free even from the feeling of possessing a body, the individual lives consciously, with open eyes, a life of dreams. This life, however, is a purely "ego" life, a life in the present. The thoughts are directed not to the future but only to the passing day with its morphia. Soon the higher perceptions become defective. Heart and soul suffer. The limitation of the world to oneself causes moral deterioration and renders the individual ruthless even towards wife and children. His care for the latter, if present at all, is quite secondary to the craving anxiety for morphia. The poet's words" are in a figurative sense true:

Zur Warnung holt' ich sagen, Dass, der im Mohne schlief, , Hinunter ward getragen

In Traume schwer und tief; Dem Wachen selbst geblieben Sei irren, Wahnes Spur,

Die Nahen und die Lieben Halt er fur Schemem nur.

The duration of action of a single dose, which now amounts to 0.2-0.5 gr., rapidly diminishes. The drug must be inject more frequently and in larger quantities, the chain of slavery becomes shorter and tugs at the morphinist. His creditors, the brain cells, grow restive, demand satisfaction, shriek, and revenge themselves by producing pain if they are not satisfied quickly enough. If money to buy the drug is lacking, he steals or embezzles. Respectable women are said to become prostitutes in order to be able to buy morphia. At the beginning of the passion for morphia one pleasure is replaced by another still more delightful, but now a state supervenes wherein the brain after an injection reacts as before, but between two doses, if it is not immediately satisfied, makes its presence very disagreeably felt as soon as the effect of the last dose begins to pass away.

The passage of time gives birth amid excruciating pains to the last stage; the awakening to consciousness of the fact that the morphinist is given over body and soul to the drug, that he has unconditionally surrendered. Will-power is completely paralysed. Even the effort of will needed to carry out the simplest act is now lacking. The perpetual fight between the necessity for decision and the incapacity for it, as well as the consciousness of inferiority and misery with which the victim is obsessed, cause terrible suffering. Even in his dreams this mental torture is continued, for the happy, delightful past is brought into tormenting comparison with the despair of the present. It is not possible to face each day's work without exaggerated doses of the drug. Its aid enables the morphinistic surgeon to strengthen his trembling hand, to clear his dim eye and his obscured judgment—I have seen this terrible condition in one of the most capable surgeons of the day who had done the work of a genius in his time. The rider can win the race, the judge can pronounce a just judgment, but the will-power, scourged into activity, soon fades away. If the brain is not completely sodden with the drug, compulsory abstinence brings about mental and physical restlessness, inconsiderateness towards others, especially dependents. Many pages might be filled with the description of these symptoms. We could tell of morphinistic judges who in this state deal unjustly with the accused, of high officials who vent the nervous troubles caused by abstinence on their subordinates; even of a professor, long since dead, who could not treat humanely the student he was examining unless his attendant, who was bribed by the students, had some morphia syringes in readiness for him.

In the case of such persons every contact with the higher sentiments, love of the family, good humor, faith, reverence, the beauty of nature and the activities of human life is lost, and that forever. The sunny side of existence, which even in the case of the most poor and desolate being possessed of a clear brain brings some moments of subjective satisfaction and happiness, never lightens the darkness surrounding the morphinist at this stage. Only the picture of long-lost hours of ecstasy remains framed by repentance in his memory. The regret for the life which has been lost is the Miserere of annihilation.

As a consequence of the disorder of the brain-functions organic troubles gradually appear. The brain, the regulating center of so many diverse organs, is slowly but surely paralyzed. Nutrition suffers, the general appearance is bad, emaciation sets in and the capacity for work is greatly reduced. Morphia is able to enforce physical labor only in toxic doses.

During this period the morphinist generally consists of little more than skin, bone, and palpitating nerves. Sticky sweat is excreted, especially at night, from the whole body or from the head alone; the appearance and personal hygiene are neglected. Frequently attacks of fever with ague, headache, and oppression occur. There is a tormenting itching of the skin. Gastric pains, colic, diarrhoea with the soreness of the anus, probably occasioned by an unknown decomposition product of morphia; sometimes disturbances of the urinary excretions, conjunctivitis, lacrymation, disturbances of accommodation and dullness of vision set in.

Sexual life suffers. At the beginning of morphinism the excitability of the sexual functions increased, but now it diminishes to impotence: Infringit stimulos veneris opium. The examination of the semen of a morphinist who had injected 0.3-0.5 gr. of morphia daily for several months, disclosed quite immobile thin spermatozoa which could not be rendered mobile even by chemical agency. In morphinistic women disturbances of menstruation amounting to amenorrhoea set in. If conception takes place the fetus may be born normally or abortion induced. But even in the former case there is a possibility of its early death by reason of its feeble vitality. The semen or the ovum of the mother may be morphinized to such an extent that its normal functioning is injured, as occurs in cases of poisoning by other substances such as lead-poisoning in the case of lead workers, or mercury and carbon bisulphide poisoning in industry. After birth the child of a morphinistic mother may exhibit symptoms of the withdrawal of the drug.

Reduced to this state, the morphinist seeks help. He wishes to be liberated from the morphia that is killing him. It cannot be predicted even approximately when this moment will arrive, nor how long the individual is capable of working, thinking, and living under the toxic influence, before he forces himself through the gates of a sanatorium. His miserable existence may last for a long time before he comes to this decision. The feeling of inability to carry on may appear after three or six years, or even much later. The morphinist exhausted by the burden of the drug is nothing more than a ruin, whose crumbling into a mass of debris can seldom be avoided. It is of no consequence to the final result whether withdrawal is attempted suddenly or in stages. In the former case the suffering produced is serious: and excitement of the hitherto impotent sexual sphere, restlessness, morbid craving for morphia, violent crises of fury and destructive mania occur, leading often to delirium and attempted suicide. Besides these symptoms ex- cruciating pains are felt in various nervous centres; vomiting, diarrhcea, angina pectoris succeeded by cardiac collapse set in for some days. The gradual deprivation of the drug involves after every diminution of the dose a renewed cry on the part of the cerebral cells for the full amount to which they were adapted. In both cases the morphinist may be delivered from immediate desire for the drug, but that is all. About 80 to 90 per cent of these wretched beings, perhaps even more, have relapses. In this figure are also included those who without being treated in a sanatorium have been temporarily freed from their vice by imprisonment.

The use of other narcotic or stimulating drugs as substitutes for morphia merely augments the evil, since both, the old and the new, are then employed at once. A state then appears which I have named "twofold craving." Forty years ago I drew attention to the combined use of several narcotics, for instance that of morphia with chloroform, ether, or cocaine."

General Questions Connected with Morphinism

Morphinism as a state of intellectual constrain is more dangerous than alcoholism. The recognized and approved rules with respect to alcoholism concerning exclusion from or access to situations of responsibility are valid to a far greater extent with respect to morphinism. Both I myself and others after me have insisted on this.

The morphinist is mentally affected to a greater degree than the drunkard. Such a person cannot be left in positions such as those of examiner, judge, public official, etc., where he may exercise an influence over the welfare of his fellow-creatures. Not only their mental aberrations but even their physical inferiority should prohibit morphinistic workers from holding or continuing to hold responsible positions as engine-driver, pointsmen, permanent-way men, etc.

In the advanced stage of morphinism even the capacity for correct judgment is lost. The poison brings about profound changes in the personality. These manifest themselves in permanent disturbances of will-power and activity which are not only opposed to ethical and moral principles but must also be regarded as illegal if the same laws are applied to morphinism as to alcoholism. It was an error of judgment caused by lack of experience of the ways of the world, which led a French court to declare valid the will of a morphinist who had committed suicide after leaving his fortune to his mistress. The court was moved to this verdict by the very frequent but foolish argument that if responsibility is recognized in criminal law this should likewise be done in civil law. The law, which protects humanity against the drunkard by all kinds of safeguards and punishments, has hitherto ignored morphinists, cocainists, and other narcomaniacs, because jurists are not disposed to leave to the medical profession the statement, substantial proof, and solution of medical problems which involve the relationship between the individual and public order."

The Committee of the League of Nations which deals with the world-problem of narcomania apparently makes the same mistake, for it has not to my knowledge secured the aid of a competent medical expert in relation to these matters. Medical men throughout the world should protest unanimously against decisions in this matter being left to laymen.

In 1925 the draft of the German General Penal code contained a paragraph entitled "Abuse of Toxic and Inebriant Poisons", and paragraph 341 deals with the "Supply of Inebriant Poisons" as follows:

"Whosoever without permission supplies any person with opium, morphia, cocaine, or other narcotic inebriant poisons shall be liable to a term of imprisonment not exceeding two years or to a fine."

This paragraph, which probably was not edited by a medical man, is in this form an absurdity. According to the text the force of the law could be directed, for instance, against a person who supplied another with alcohol, spirit of ether, ether, benzine, ligroine, etc. The sale of the substances mentioned above is unrestricted, and the person demanding them can apply them according to his own free will as "toxic and inebriant poisons."

The morphinist should not only not be allowed to transact his own affairs but should also be compulsorily interned in a sanatorium. Justification for placing him under tutelage" can be found in the fact that he is unable to manage his affairs on account of the state of his brain and because in many cases he exposes his family to poverty in order to procure the drug. He should be placed on the same level as the inveterate drunkard." Morphinism should also be a ground for divorce. In an advanced stage of intoxication the morphinist becomes impotent, and this renders him unfit for the responsibilities of marriage. A married morphinist cheats his wife of the happiness of life in every way. She also has the right to fulfill her physiological destiny. In such unions the husband often, in his consciousness of guilt, tempts his wife to morphinism.

The German courts have come to different decisions as to the irresponsibility of morphinists, cocainists, etc. They have, for example, punished a morphinist who had falsified prescriptions in order to obtain the drug, while acquitting a morphinistic lawyer who embezzled. A man who after being severely wounded in the war had become a morphinist and constantly committed small thefts and frauds in order to procure the drug was also acquitted. Irresponsibility must be admitted in respect of the greater number of offences committed by drug victims. From a toxicological point of view no difference can be established among morally defective but "intellectually intact" morphinists. The one involves the other, even though laymen consider the intelligence of these drug victims quite undisturbed. If life is subjected to the constraint of a morbid passion, a morbid modification of the personality results, to which in many cases paragraph 52 of the existing penal code must be applied.

The most diverse infringements of the law have been alleged to be the result of morphinism. Recently a thief demanded acquittal because he was under the influence of morphia and not fully conscious when committing his crime. A chemist who had escaped from a sanatorium where he had been interned for demorphinization made use of his liberty to commit a sexual murder. He confessed, but stated that he was intoxicated with morphia. The annals of jurisprudence furnish very many instances of illegal acts committed by morphinists. In order to escape from the suffering of the morphia-inflamed ganglia of the brain with which they are afflicted, they break into pharmacies, drug stores, and hospitals, defraud, embezzle, counterfeit prescriptions (this last was once—mildly—punished); or even when supplied with morphia, they may commit crimes against humanity so that the judge has to decide as to their responsibility.

In the series of cerebral disorders which I have described above (which may explain certain abnormal actions) there occur certain states of abnormal mentality which are rare during the normal course of morphinism but frequent as a result of sudden enforced abstinence. Those patients who have lost the ability to differentiate between right and wrong, true and false, may, if they are predisposed, exhibit psychoses which in their symptoms and course bear the character of an acute mania and cannot be distinguished from confusional insanity. In other case the malady is similar in character to paranoia. The variety of the forms of mental disease which may afflict the morphinist, and which have hitherto not been anatomically explained, peremptorily demands such an attitude on the part of the law as I have indicated above.

Paragraph 17 of the new German penal code in preparation—corresponding to paragraph 52 of the old code—provides for an alleviation of the penalty in case of diminished responsibility resulting from morbid disorders of the mental faculties or mental weakness, but makes an exception of persons who voluntarily lose conscious control of their acts by inebriety. Substances causing cerebral disorders other than alcohol are not mentioned. Whether the law will make an exception of voluntary morphinism is questionable.

Measures against the Extension of Morphinism

The ruling classes in all civilized countries are aware of the increasing danger of the abuse of morphia, cocaine, and other narcotics. A deluge of rules and laws has been the result. Nearly all of these are regulations framed round a green table by officials of ministries of health who have no experience whatsoever of this matter. Many of these enactments years ago proved their ineffectiveness and have been discarded. They all aim at restricting the supply of the drugs to purely medicinal uses, at the centralization of the wholesale supply and the strict supervision of pharmacists. According to the German "Opium Law" all medical prescriptions containing opium, morphia, cocaine, or heroin must be preserved by the pharmacist even when the medicine prescribed is not to be repeated. The prescriptions of copies of them have to be preserved and accessible for at least three years. In Prussia a regulation exists penalizing doctors who do not take due care in supervision of nurses and attendants when supplying narcotic remedies. During the Hofle trial I explained how easily morphinists may be created by lack of supervision in these cases. It was disclosed that at that time the strongest narcotics might easily be procured from subordinates in the prison-hospital without any control. I could not but characterize this as the application of the canteen system to these most dangerous drugs. The consequences were inevitable.

In other countries, for instance in England, the pharmacies are subjected to very strict control. Among other things the prescriptions, which must be preserved and copied into a register, are in principle only allowed to be made up once, or, if specified by the physician, up to a maximum of three times. The possession and the illegal use of morphia and cocaine not prescribed by a doctor is punished with imprisonment. In the British Malay States the "Deleterious Drugs Enactment" of September, 1925, exclusively reserves the import and export of the drugs specified in the law to the superior officer of the health department. Physicians and pharmacists can only obtain supplies and procure these drugs through the medium of the medical officers. The law prohibits the manufacture of morphia and cocaine and their salts and the possession of more than twelve legal doses of any narcotic or of preparations thereof, whether for internal or injecting purposes, without permission.

All legislative safeguards may be and are eluded. They are necessary, but we cannot depend upon their strict observance. The passion of the morphinist and the avarice of the dealer, even when the latter is the State itself, break down all barriers. At this final conclusion all those who are acquainted with the facts arrive. With extraordinary effrontery certain proprietary articles are sold (for instance Trivalin) which contain not only morphia but also cocaine. For every thousandth of a gramme of the latter there is a disproportionate increase in the danger of the mixture. Unconscious of the far-reaching consequences of their prescriptions, medical men become accomplices in such mercenary businesses. Other dealers sell morphia wholesale to those who will pay their price. The circumstances guarantee discretion on both sides. Many other proofs could be cited of the difficulties, not to say impossibilities, encountered in the attempt to remedy this evil.

It is difficult to say whether some kind of international State monopoly of these substances, such as has been suggested, would be able to combat this growing menace to mankind and the vile traffic to which it gives rise.

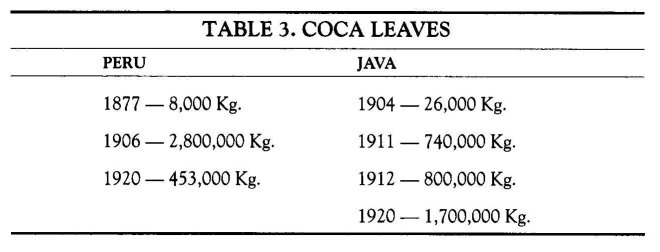

The League of Nations in Geneva may be of help. The discussions of the Opium Conference have up to the present (1925) jeopardized the hopes that were based on the international regulation of the production of and traffic in opium. America, which considers herself commercially disinterested in the subject, proposed a limitation of the production of raw opium and coca leaves in the countries of origin to the quantities necessary for medical and scientific requirements. The aim in view was "to offer a gleam of hope to millions of families who suffer from the consequences of the abuse of opium and other narcotics." India did not agree to such a limitation, and earned the reproach of being influenced in opium politics by financial and commercial considerations. Japan also formulated demands in respect of opium to which India refused to agree. A gradual reduction of the traffic in opium and a simultaneous decrease of the evil for fifteen years were taken into consideration. But this proposal of compromise was also rejected. The Opium Conference has practically broken down. Napoleon once said in the Council of State: "Le commerce n'a pas de patrie." If the activity of commerce in the field of narcotics were characterized properly and plainly, the reproach levelled at it would be a much more serious one.

Finally, I am absolutely certain that no substitute exists which, without containing opium or any of its derivatives, can cure the morphinist of his passion or even alleviate it. All the specifics that have been advertised and sold at high prices with this end in view are based on error or fraud. Years ago a remedy of this kind, of America origin, which was said to contain piscidia erythrina, was widely sold under a false name. It contained morphia, and after I had disclosed the fraud, disappeared.

Neither combretum sundaicum, nor mitragyna speciosa and mitragyna parvifolia, the leaves of which are smoked in Perak as "anti-opium," nor blumea laciniata can secure a mental calm in the least resembling that obtained from morphia-containing substances, nor maintain a natural combat against the existence of the craving.

In morphia are combined a blessing and a curse. If it is dispensed by the hand of the physician its power is divine. There are human beings who spend sleepless nights in excruciating pain, who because of some disease racking body and soul foresee a morrow and a future covered with a mantle of darkness and night, who curse their life because death will not come, who lead a wretched existence as a result of the destructive powers at work within them, and with certain death in view; to all such the physician should bring the beneficent morphia to alleviate their suffering, to reconcile them to their fate, and to sweeten death. But not to hasten death! He is not authorized to do this, although in morphinism life and death often meet. He should only use the drug in those diseases compared with which morphinism can be regarded as trivial. He should take care not to dispense it injudiciously as an anaesthetic. To do so is to create morphinists who acquire a moral blemish if over and above the anesthetic application they find pleasure in its use, or continue to employ it solely for the purpose of obtaining delightful sensations. Such can expect no mercy, though it must be admitted that they are subject to the constraint of the morphia-craving cerebral cells, which can break down a weakly resistant will-power. Those others alone deserve pity whose life has become a martyrdom into which morphia brings soothing balm. The words of the German physician-poet, inspired by the Muse with deep human sympathy, are true indeed:

Pflucket den Veilchenstrauss, die ihr den Mai ersehnt,

Die ihr geliebt euch wisst, schmuckt euch mit Rosenpracht. Aber des Ungliicks Sohn, der nichts sich wunscht als Vergessen, Wahle den Mohn sich zum Labsal!

Wenn ihn die lange Nacht qualet mit bitterem Schmerz, Wenn er sich schlaflos walzt, stahnend im Folterbett,

Da lang alles entschlief and der Zeiger der pickenden Wanduhr Stocket im schtafrigen Kreislauf.

O, wie segnet er dich, der Gequalten Trost,

Den heilkundig ein Freund in des Vergessens Prank

Darreicht, wenn ihm das Leid an dem brennenden Auge sich schliesset, Und die begluckende Gottheit.

Naht auf dem Wagenthron, den ein Eulenpaar

Ohne Gerausch bewegt! Traufle, o traufle, o traufle ihm Huldvoll perlenden Tau, dass die schmachtende Seele sich Labe. Herrlicher Konig der Traumwelt!

Zaubre die Jugend vor seinen entzuckten Geist,

Lass ihn nock einmal schaun glucklicher Tage giant, Maiduft hauch' ihm gelind in die schmerzverdunkelt Seele, Hoffnung der besseren Zukunfti19

CODEINE AND ITS DERIVATIVES: DIONINE, HEROIN, EUCODAL, CHLORODYNE

All those substances derived from opium or morphia and containing the morphia nucleus, with names such as Pantopon, Holopon, Glycopon, Laudopan, Nealpon, Eumecon, Trivalin, have in common the property of evoking an ardent desire for their prolonged use. This effect may have less serious consequences than those caused by the original substances; the craving may be less violent, but its action on the individual and the distressing results of compulsory deprivation of the drugs are the same.

Codeine

The widely-used drug codeine is a morphia alkaloid, contained in opium, and is chemically mono-methyl-morphia. To believe that in users of the drug the organism acquires greater ability to destroy it is an error. In dogs 80 per cent of the codeine is excreted with the urine. The conclusion has quite erroneously been drawn from this fact that the drug cannot give rise to a habit because the amount of its destruction in the body, even on prolonged use, is very inconsiderable. It has been said that instead of an habituation to the drug an increased sensibility towards it is manifest. This is an example of the precautions which must be taken in applying to man the results of experiments on animals.