| - |

Drug Abuse

III DEFINING THE GOVERNMENT'S ROLE

In the preceding pages, we have defined and applied a process for determining when a particular psychoactive substance should be available, and the conditions under which the government should intervene coercively in the life of a person who has chosen to consume a substance outside the prescribed channels of availability. The final step in the policy-making process is to decide how to organize the efforts of society's institutions, both public and private, to achieve the stated social objectives.

The availability and consumption-intervention decisions essentially fix the role of the legal system in the public response. Though tied to social context, these decisions are guided by fundamental philosophical precepts. They establish the limits of appropriate policy, but they do not assure success. Effective pursuit of the discouragement and preventive policies depends far more on the capacity of non-legal institutions to mold individual behavior. In the succeeding sections of this chapter, the Commission will attempt to provide general guidelines for framing the institutional response. First, however, some comments regarding the relative roles of government and the private sector are in order.

GOVERNMENTAL COMPETENCE

The governmental response to drug use or to any other complex behavioral problem at any particular point in time depends upon prevailing philosophical notions of the legitimacy of governmental actions on the one hand, and political decisions regarding priorities and competing needs for governmental energies and resources on the other. Interposed between the issues of philosophy and politics is the question of governmental competence to perform legitimate roles for which resources are available.

A salient feature of 20th Century public policy, particularly in the last three decades, has been the assumption that the government has the primary responsibility to satisfy basic human needs. In trying to fulfill this responsibility, the government has often weakened its moral authority by threats which it cannot enforce and raised undue expectations by promises which it cannot keep. Nowhere is this phenomenon more apparent than in the government's response to drug use.

Governmental credibility has suffered from the continuing failure to eliminate disapproved drug use. The government has not been able to make the drugs unavailable or to dispell the demand for them. Nor has it succeeded in rehabilitating drug users, despite vociferous proclamations by some that rehabilitation is the answer to the drug problem. The government cannot cure the illness of drug dependence simply by devoting large sums of money to the task of funnelling patients through a treatment system.

When performance did not meet expectations, the government, instead of questioning underlying assumptions, has made more unenforceable threats and more unfulfillable promises. This response has heightened the tension between drug policy and other social and political values, and perhaps exacerbated the drug problem itself. Moreover, as the spiralling process continued, the problem has become institutionalized, so that both its definition and the response to it have been frozen into place.

As government has expanded its role, particularly at the federal level, private institutions have tended to defer to the public agencies. Because government has appropriated to itself almost all responsibilities with regard to the drug problem, other institutions have abdicated their responsibilities. Institutions such as the family, the church, community organizations, and the school, with the greatest capacity for dealing with individual behavior, inhabit the fringes of the response when they should be at the center.

The Commission strongly believes that drug policy must redefine the relative roles of government and non-governmental institutions in dealing with drug use. While the government cannot suddenly abandon all the activities where its competency is limited, especially when the private sector has become dependent on governmental resources, it must, nevertheless, redirect its energies. During the transition phase, government must take necessary steps to revitalize the other social institutions.

GENERAL GUIDELINES

The primary object of governmental concern should be the establishment and enforcement of restrictions on availability of psychoactive substances, either through regulatory or prohibitory mechanisms. Second, the government must direct and sponsor continuing research into all matters relating to drug-using behavior, in order to gather and interpret the information required for rational policy decisions. Third, the government has a major responsibility to fund, evaluate, and, where absolutely necessary, provide directly, comprehensive treatment and prevention services.

These are the areas of governmental competence. The success of governmental response in the third area should not be measured by drug-using behavior in general, but by how well the individual prevention and treatment programs perform their stated objectives in terms of specific client populations. In short, the government cannot be held accountable for the shortcomings of the entire network of social control. The private institutions closest to the individual are the ones which best inculcate the values and norms necessary to minimize irresponsible drug-using behavior, to encourage responsible decision-making, and to discourage drug use in general.

The government should not expect to achieve unanimity regarding the value judgments underlying a discouragement policy. In a pluralistic society emphasizing individual choice and the free flow of information, the government must accept the dissemination of ideas at variance with official policy. At best, the government can assure that the official view is accessible, and hopefully persuasive, to those who are inclined to study it.

Because the current governmental response has not been geared toward realistic objectives and appropriate priorities, the Commission believes that it must be reorganized. Accordingly, in the next section of this chapter, we will devote our attention to a temporary solution of the problems with the existing governmental organization. In the succeeding sections of the Chapter, taking into account our basic conclusions regarding governmental competence, we will devote separate attention to those areas for which a directed governmental program is crucial: treatment and rehabilitation, prevention, and research. Finally, we will turn our attention to the private sector, identifying those responsibilities which various private institutions must fulfill if the basic social policy objectives are to be realized in the years ahead.

ANALYZING THE GOVERNMENT RESPONSE

The last four years have seen a dramatic upsurge in the amount of government resources allocated to combatting the drug problem. At all levels of government, new agencies have been created and old agencies have developed new specialties.

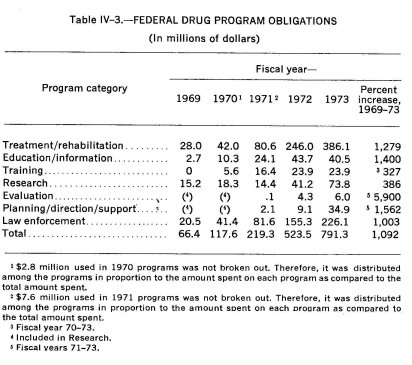

In fiscal year 1969, the federal government spent $66.4 million for all phases of its drug "abuse" program, including law enforcement, treatment and rehabilitation, education, training, research, and evaluation. By fiscal year 1973, total funding had reached $791.3 million, an increase of 1092% which is still heading upwards. (See Table IV-3) Yet, as federal spending approaches the $1 billion dollar mark, establishing an entirely new "drug abuse industrial complex," no one has systematically analyzed either the problem to be solved or evaluated the solutions to be employed.

To assess the effects of this outpouring of public resources, we must begin by describing the organization when there has been any, and the allocation of responsibilities among and within the levels of government.

An Overview of the Government Response

Until the 1960's, the federal government had only a minor financial 'involvement in the drug area. It sponsored limited research programs, operated two public health hospitals for drug-dependent persons, carried out law enforcement activities with small criminal investigative agencies, and funded a few informational and educational programs.

Drug use and misuse was viewed as primarily a state and local problem and state policy was reflected almost exclusively by the Uniform Narcotic Drug Act and the activities of vice squads in local police departments. Although the concept of treatment and rehabilitation for drug-dependent persons was enshrined in legislation, few states actually provided such services. There were no drug education programs, no information programs, no drug abuse agencies, and no federal assistance ; nor were any such programs requested.

The explosion of drug use in the mid-1960's found the inventory of available public resources woefully short. States and localities suddenly discovered an urgent need for programs of drug prevention, education, information, training, treatment, and rehabilitation. The problem seemed particularly grave in the major urban areas, where a rising urban crime rate was associated with the apparent "epidemic" in drug use. The cities, of course, were the areas least able to provide the resources for mushrooming treatment and law enforcement needs, and communities and states turned increasingly to the federal government for financial support and policy direction.

The federal government's initial response was. for the most part reflexive. No overall plan of action was formulated; monies and attention were expended on a first come, first served basis. Finally, a program was patched together by setting up divisions within existing departments and agencies, and beefing up already existing programs. The result was that 13 federal agencies in, eight Departments, had piece-meal authority to provide the necessary funds and assistance to the states.

Not surprisingly, duplication of effort, uncertainty of direction and lack of interagency coordination marked the early campaigns in the federal "war on drugs" (Booz-Allen, 1973). The crisis conditions under which the federal government operated precluded interagency and sometimes even intra-agency cooperation. Because federal policy lacked direction and coherence, the funding of programs at state and local levels was a haphazard enterprise. Formula and block grants were distributed to the states without provisions for monitoring and evaluation. The cry, "do something," forced the federal government to spend the money without an opportunity to evaluate the programs in advance or to assess their likely impact on larger social welfare policies.

The rapid increase in federal spending made "drug abuse" a "hot" area, where money was available with little exercise of control. Persons involved in other big government spending programs whose funds were drying up (for example, the poverty programs) switched into the drug field and became instant "experts." Ex-users of heroin were in demand as counselors, lecturers and program designers. Pamphlets, movies, lectures, crisis centers, almost anything that could be characterized as anti-drug, had a reasonable hope of receiving funds.

Emergence of a drug abuse industrial complex ensured perpetuation of the crisis psychology surrounding the drug problem. Since public funding is in large measure a function of public concern, agencies and programs had reason to maintain the country's anxiety about drugs. For example, to obtain funds, a locality must show it has a drug problem ; chances of funding improve if the problem appears to be growing. Once the money is granted, staffs are hired and the program goes into operation, there develops an institutional reluctance to see the problem get smaller, for so too will the volume of federal or state funds.

The funding mechanism is so structured that it responds only when "bodies" can be produced or counted. Such a structure penalizes a reduction in the body count, while it rewards any increase in incidence figures and arrest statistics with more money. Those receiving funds thus have a vested interest in increasing or maintaining those figures. The statistics, in turn, fuel public and bureaucratic concern, and assure that the problem continues to be defined incorrectly. There is no incentive for local communities to maintain a cautious, unemotional approach to drug use.

In short, the professed goal of social policy is to reduce or eliminate drug use, but the government's response produces financial incentives to magnify the problem. The system seems to reward failure or status quo rather than success; it guarantees a continuing sense of crisis.

The present system of distributing federal money tends to institutionalize "drug abuse" as an ongoing problem within the federal government as well as without. A large federal drug bureaucracy has emerged, displaying the common propensity of bureaucratic infrastructures to turn short-term programs into never-ending projects. Despite well-meaning efforts of sincerely concerned individuals in government, the organization begins to take on a life of its own and its goal becomes survival.

To justify ongoing programs, the drug bureaucracy must simultaneously demonstrate that the problem is being effectively attacked, and that it is not diminishing. Often, the same facts may serve to show both that programs are working and that the problem is growing : for example, increased seizure and arrest statistics in the area of law enforcement demonstrate a more effective law enforcement response and also justify requests for more resources, because those same statistics suggest a growing problem. Similarly, rehabilitation centers cite numbers of people in treatment as proof of "successful" cures and as evidence of the need for larger facilities; informational programs point to the number of requests for pamphlets and other materials. While this goes on, agencies within government jockey for better position among themselves in an attempt to preserve or expand their jurisdiction and to maintain or increase their appropriations.

Throughout this process fundamental assumptions are not questioned, programs are not evaluated and the problem is perpetuated from fiscal year to fiscal year. "Drug abuse" spending in the last decade can be summarized thus : an ill-defined problem emotionally expressed, led to ill-defined programs, lavishly funded.

The Special Action Office: A Stopgap

To meet the problems mentioned above, the Special Action Office for Drug Abuse Prevention (SAODAP) was created in 1972 to coordinate federal activities and agencies, implement short-term plans, devise long-term strategies, and assist the states in their management of federal money in the "drug abuse" field. Congress also intended that this office identify new trends in drug use, develop new procedures for treating drug-dependent persons and devise new education and prevention strategies. To this end, SAODAP has received broad authority to contract for services, to make grants and to evaluate programs in operation.

Detailed program authority, however, still remains outside of SAODAP control, and so, in trying to coordinate the federal effort, that Office must contend with the ambitions of the other federal agencies in the area, each competing for its respective share of the federal drug effort and promoting its own particular bias. For example, the National Institute of Mental Health stresses the mental illness aspect of the problem, the Department of Justice emphasizes law enforcement aspects, and the Social and Rehabilitation Service highlights the need for vocational rehabilitation. All of these approaches are necessary, of course, but in the correct proportions. In the competition for appropriations, however, each agency feels it must promote its own approach to the hilt, relegating other programs or policies to a secondary role.

The confusion in policy follows the federal funds into state and local drug use prevention and treatment programs, where it is compounded by bureaucratic infighting at that level. At least 33 separate federal grant programs, administered by different agencies, are available for drug prevention and treatment programs, not to mention indirect sources of money such as Emergency Employment Act funds used to hire community workers 33 (Mushkin, et al., 1973). State agencies, attempting to comply with the requirements of the various federal funding agencies and their different ways of doing business, cannot avoid the confusion resulting from overlap of federal activities and conflicts between individual agency biases (Booz-Allen, 1973). Instead of coordinating state programs, federal supervision has in many instances only further scattered their energies. SAODAP's efforts to correct this situation have been considerable, but the fragmentation of authority threatens to defeat its attempt to organize federal and state activities into an integrated response, under clear and understandable policy guidelines.

Failures of the Present System

Our review of the establishment of the "drug abuse industrial complex" and of the forces which keep it in motion, suggests that the present governmental response fails in nine major ways :

• The nature and extent of drug use have not been adequately identified.

• Definitive goals and objectives of drug-related functions have not been sufficiently developed at any governmental level.

• Effective planning is not being, and cannot be carried out under present conditions.

• Lack of meaningful plans, in turn, has made effective control of resource allocation impossible.

• Limited coordination among federal agencies has resulted in duplication, overlap of efforts and a disregard of problem areas requiring action.

• Formulating and administering drug policy is not the primary mission of many federal agencies performing important drug-related functions.

• Because goals and objectives have not been defined, programs cannot be evaluated in terms of their effectiveness.

• Programs are not being evaluated in terms of their efficiency.

• Drug and alcohol activities are treated as two entirely distinct functions and their policy directions are not coordinated.

While most of these deficiencies have been discussed in terms of the evolution of the governmental response, we must now examine them in even greater detail in order to determine how the governmental response can be properly organized.

1. Identification of the nature and extent of drug use

Most federal agencies now rely on state agencies to identify the extent of the drug problem and to assess the need for treatment and prevention programs in a given area. Since the state agencies also lack the resources and information base to assess the need objectively, they in turn look to grant applicants and local community bodies to make these judgments. Applicants and community level agencies, naturally enough, tend to rely on subjective appraisals, often colored by self-interest, to determine local requirements. The distortion which filters up from the local level through the state to the federal funding agencies results in policies which misallocate resources, overemphasizing some aspects of the problem, and ignoring others.

Until the government develops some objective measure of the nature and extent of drug dependence and other aspects of drugs use, it can hardly assess the need for different types of prevention and treatment programs. The 'Commission, in its own attempts to define the problem, has conducted two national surveys but they are only a starting point in gathering the needed statistics on incidence and prevalence. If policies are to be predicated on actual needs for services, planners will require much more detailed and extensive surveys. SAODAP has been intensively involved in trying to develop such measurements and the Commission urges that SAODAP continue to make national surveys of at least the same calibre as those conducted by the Commission.

In particular, there is an urgent need for measurement of the drug-dependent population, so that sufficient resources can be directed to the segments of the using population where the problem is most serious. There is no useful estimate of the number of heroin-dependent persons in the United States today; all current estimates rest on a series of tenuous assumptions and are unreliable for policy planning purposes.34

Second in priority only to determining the scope of the problem is an inventory of the resources, in terns of skilled manpower, available to meet it. The Commission urges that federal agencies immediately conduct a joint review of the situation, to determine exactly the size and shape of the country's capacity to respond. The review should cover training resources, as well as number and kinds of skilled personnel already available.

2. Definition of goals and objectives for drug-related functions

Most drug prevention and treatment programs and activities have come into existence without any explicit definition of their objectives.

Generalizations about overall objectives have been made, but little in the way of functional implementation has been designed at either federal or state levels. Moreover, most federal agencies have not defined their own specific objectives in these areas. There is still a lack of interagency coordination. The creation of SAODAP was a legislative and executive attempt to overcome conflict in bureaucratic biases.

At the state level, some goals and objectives have been developed, but specificity is impossible as long as federal requirements are unclear or in conflict. Many state programmers have complained that they receive one set of signals from one federal agency and an opposite set from another (Booz-Allen, 1973).

In addition, many of the local drug programs and activities have not been required to state their objectives in terms of measurable outcomes. Even those who do so are not likely to have their measurements scrutinized by the federal or state funding agencies, because there is insufficient manpower for this task. Moreover, operating agencies generally resist and resent objective evaluation. This is especially true in law enforcement, where challenges to the basic operational assumptions, critique of strategies and appraisal of results are viewed as an effort to undercut enforcement itself.

To correct this situation, federal agencies providing funds to state and local, public and private drug programs should require a comprehensive statement indicating (1) the nature of the service; (2) the population to be served; (3) populations which will not be served and why; (4) concrete evidence of coordination with other relevant services and agencies. At the same time, the federal agencies should furnish the programs with technical expertise, so that they can evaluate (1) the impact of services; (2) the scope of services; (3) the cost of services; (4) the degree to which the target population is being served; and (5) the degree to which an appropriate client population is being under-served.

3. Effective planning

Without identifying the problem, assessing the need, defining objectives and stating the criteria for success, meaningful planning is impossible. The present system has not completed any of these managerial processes, which must be completed if new plans are to have a reasonable chance of success. Creation of SAODAP was an important first step, but it did not go far enough. SAODAP is attempting to develop a coherent plan of action, but, at present, it appears unable to bring the disparate elements together.

4. Effective control of resource allocation

As in other areas of federal funding, the drug "grantsman" has evolved, attuned to various bureaucratic predispositions and able to prepare grant applications that fit perfectly the bias of the funding agency. One consequence of this is that application for federal money tends to describe the problem in terms of the available programs, rather than to propose programs designed to meet an objectively assessed need. Another consequence is that the successful grantees become a self-perpetuating, and to some degree exclusive, circle of experts. Persons with new ideas or approaches who do not belong to this group have difficulty in moving their applications past peer review procedures established by the government. An examination by the Commission of various drug programs throughout the country gives the impression that grantsmanship may often play a greater role in the "success" of large programs than a given program's ability to achieve its stated purposes.

5. Coordination among federal agencies

Coordination among federal agencies remains inadequate despite the continuous efforts of SAODAP and the occasional expressions of Presidential concern. Federal agencies compete with each other in making funds available for similar projects, duplicating the effort involved in processing and evaluating grant applications, while some other concerns are left unattended.

Interagency rivalry and lack of coordination, for example, have seriously hampered prevention of illicit drug trafficking. A sometimes bitter dispute exists between the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs and the Bureau of Customs regarding which agency has primary authority to carry out investigations overseas and in cases where illegal drugs cross the border into the domestic market. This quarrel has persisted despite repeated efforts to resolve it by the President, by the Ash Council on Government Reorganization, by the Secretary of the Treasury, and by the Attorney General. It has often kept the two agencies from sharing intelligence and effectively coordinating investigative activities.

6. Drug-related functions within agencies whose primary mission is not solving drug problems

When drug-related functions reside within agencies whose primary missions are not drug related, such as the Department of Housing and Urban Development, the Office of Economic Opportunity and the Department of Defense, agency decision makers tend to give secondary emphasis to these functions or to use them as a means of increasing appropriations for their larger projects. In many instances, the drug component in a program such as Model Cities is either neglected or downgraded, and no attempt is made by the agency to coordinate it with other drug programs operating in the same geographical area. Predictably, a great part of the duplication in federal effort occurs in this type of program. SAODAP has been working to relate these activities to the overall effort, but the lack of detailed program authority again impairs that Office's ability to integrate these programs with others already in existence.

7. Evaluation of programs in terms of their effectiveness

The fact that drug use prevention programs are spread throughout the government impedes efforts to evaluate their effectiveness for one bureaucratically simple reason : if one agency submits to evaluation and other agencies do not, the evaluated agency risks that a bad appraisal will put it at a competitive disadvantage to the non-evaluated agencies.

Success in treatment of drug users, for example, has never been adequately defined nor has the comparative effectiveness of different treatment modalities been determined Short of avoiding gross mismanagement, no one has decided what constitutes effective program management, and no one has yet conducted a cost/benefit analysis comparing one program with another. Because each individual modality works for some drug-dependent persons, different treatment programs and services proliferate and compete with one another for funds, each claiming that its approach is successful. Unable to evaluate program effectiveness, federal and state funding agencies usually rely on narrative reports prepared by the treatment programs themselves as a substitute for objective appraisals of performance.

8. Evaluation of programs in terms of efficiency

Funding and operating agencies agree on the importance of allocating financial resources in away that will promote efficiency in governmental programs and services. The rapid increase in available funds and the concomitant deluge of requests, however, have made federal agencies more concerned with getting the money distributed than with making certain it is used effectively. SAODAP has established guidelines by which federal agencies are to determine the allocation of drug resources, but the sheer volume and fragmentation of funding decisions, coupled with a lack of program authority, prevents that Office from ensuring compliance with its standards.

9. Separation of drug and alcohol activities

At the operating level drug and alcoholism treatment programs are often closely related. Frequently, drug and alcoholism units within medical facilities have the same administrator. Above the operating level, though, the federal government and many state governments divide administration of these two programs between separate agencies. As a result, policy is confused, plans not coordinated, and programs conflict. This is one of the key areas where organizational structures complicate the task of delivering services.

REORGANIZING THE GOVERNMENTAL RESPONSE

Despite the commitment of sizeable resources, and despite attempts to solve these problems, there is still no coherent direction of the governmental response or coordination of its disparate elements. To achieve these goals, the Commission believes the following steps must be taken.

First, there is a need for more data and for a more systematic approach to data collection so that there is a reasonable basis from which to proceed. The Commission has attempted to gather data from which policy decisions could be made. Our efforts, however, are just a beginning and more is required.

Second, the Government must define its goals and objectives in a way that is consistent with the definition of the problem. Present goals and objectives are generally the product of ad hoc approaches to a specific problem which, over time, became institutionalized. To replace them, the government must develop a coherent set of short and longterm responses, based on present and future needs.

Next, priorities must be assigned. Once objectives are clear, choice of strategies and tactics will depend in part on what is possible now, as opposed to a year from now, as well as on the ranking of goals. Progress in some areas will be more rapid than in others, and the policy planner must ensure that lead times and operations mesh smoothly.

After establishing priorities, the responsibility for program efforts must be allocated. We have noted the jurisdictional rivalry between the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs and the Bureau of Customs. When responsibility is clearly defined and delegated, such bureaucratic difficulties are much less likely. There is also less opportunity for administrative buck-passing.

Assigning responsibility is not enough : agency commitment must also be elicited. In part, this is a matter of matching the function with the proper personnel. Assignments must be within the agency's realm of interest and competence. Educational functions should be given to education-oriented agencies, law enforcement to law enforcement agencies, research to research agencies.

Finally, all efforts must undergo continuing evaluation of effectiveness and efficiency. This will not only assure that present policies are being properly implemented, but will also assist the on-going decisional process and will increase the ability of the government to react appropriately to developments in the drug field or changes in use patterns.

Bringing the Drug Effort Under Control

This reorientation process has one critical prerequisite : a central organ of decision and direction. After reviewing various ways of organizing and directing the governmental response, the Commission has narrowed its focus to three possible alternatives : First, the present system might be continued in the hope that SAODAPwill more effectively utilize its statutory authority to bring some order out of the administrative chaos. Second, SAODAP could be retained, but specifically given detailed program authority as well as its present budgetary control. Third, the present system could be consolidated into a single drug agency.

To the Commission the first alternative seemed too wishful. That approach perpetuates the present system without providing any additional means of overcoming the almost insurmountable organizational obstacles which develop when authority resides in a staff-oriented agency while program implementation and bureaucratic administration resides in separate operating agencies. The second approach meets the principal objection by giving SAODAP control over the content of all federal drug programs. This would have the effect of streamlining the chain of authority since policy direction for all but law enforcement would be centralized, even though the functions themselves would remain scattered throughout the government. Such an arrangement would resemble the method by which the Office of Economic Opportunity, like SAODAP, part of the Executive Office of the President, directed the War on Poverty.

Originally, the White House had proposed program authority as part of the SAODAP complex. Congress, however, was reluctant to place such power in a Presidential staff operation, and the President himself later reconsidered his original position. The experiences with the Office of Economic Opportunity also colored Congressional thinking about SAODAP. Further, there was concern about program direction residing in one organization while the administrative controls were in another. In the final law creating SAODAP, overall detailed program authority was omitted.

While conferring program authority on SAODAP would be a useful improvement, the physical separation of the various components, coupled with the recent experience of OEO management of the War on Poverty, leads the Commission to reject this alternative, too.

Cognizant of the many political problems attendent to the third alternative, the Commission, nevertheless, recommends that all primarily drug-related federal functions be housed in a Single Agency.35 Assuming that political and bureaucratic problems can be

overcome, such an approach will allow clear identification of gaps in coordination and conflicts in objective, and should make plain to the public as well as to state and local governments the precise focus of federal programs relating to drug enforcement, treatment and prevention.

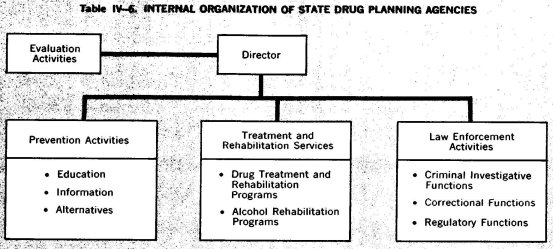

To complement the single federal agency, a unified drug organization should be created within each state government as well. Section 409 of the Drug Abuse Office and Treatment Act of 1972 requires that state plans for the development of more effective drug abuse preventive functions designate a single state agency for coordination purposes. Some 38 states have already responded to this requirement. These coordinating agencies, however, vary from state to state in authority, scope of activities, and relative position within the state governmental hierarchy.

Accordingly, the Commission recommends that each state establish a unified drug agency on the same model as that proposed for the Federal Government. A single state agency should be equipped to provide information about programs and drug use patterns, and to assume joint responsibility for evaluating federally funded programs.

The Commission further recommends that each state single agency have sufficient powers to coordinate all drug programs at the federal government. A single state agency should be equipped programs. The agency should have the responsibility of monitoring implementation of the state plan, as well as all programs operating under it, and should be required to report yearly to the designated state authority on the progress of the state effort, measured against the enunciated objectives. All state plans should budget funds for these managerial functions.

The Commission believes that the consolidation of program authority and funding, together with a direct linkage between federal and state organizations dealing with drugs, is an imperative step in the process of integrating our efforts to combat drug use. It is not, however, the last step, or even a permanent one. Its purpose and design are functions of present needs; the future may well require yet another restructuring of the organizational response.

To avoid institutionalizing the drug "problem", the Commission further recommends that the concept and accomplishments of the Single Agency be reexamined four years after its creation; and that the agency itself, by law, be disbanded within five years, its surviving components being reassigned to the agencies or departments from which they came (or into others more appropriate) and integrated into the larger social concerns of those organizations. Under this approach, both the Executive Branch and Congress will have an opportunity to determine whether this institutional response has met its goal and whether it should be continued or replaced by something new.

The Structure of the Unified Approach

The Commission recommends that Congress create a Single Federal Agency similar in its legal and political status to the Atomic Energy Commission. The agency, which might be called the Controlled Substances Administration, would establish, administer and coordinate all drug policy at the federal level and would be the principal, if not sole, point of contact with the state drug programs. The Single Agency would remain separate from all other federal departments and agencies and would be responsible for its own organization and fiscal management.36

In this regard, the Commission recommends that the appropriate Committees of Congress, in reviewing authorization and appropriation of funds for al federal departments and agencies with drug-related functions, particularly the Special Action Office for Drug Abuse Prevention, consider this year the feasibility of such a reorganization.

The director of the agency would have subcabinet rank and would report directly to the President. Because the director would determine the direction of the entire federal drug response, his appointment is a matter of particular concern. The Commission points out the irreparable injury that could result from the selection of a person who is committed to a single perspective or approach, or who sees himself as the representative of another interested agency, such as the Departments of Justice or Health, Education, and Welfare. A tendency in the Director toward ingrained views would skew the federal response in every area. In addition, the appointment of a Director should be apolitical : a demonstration of bipartisan interest and support in dealing rationally with the drug problem.

The agency should have a five year life span, subject to renewal by Congress only after full legislative reconsideration of the premises, objectives and implementation of national drug policy. At the end of the agency's fourth year, Congress should appoint an independent commission with a one year life to conduct a complete policy review, as well as to evaluate the agency and its achievements.

In order to perform its task adequately, the Commission recommends that the Single Agency have the authority and capability to do the following :

• Distribute and monitor block or formula grants to states for drug dependence treatment, rehabilitation, prevention, education, and law enforcement programs.

• Coordinate all drug-related programs which remain external to the agency itself, such as those of the Department of Defense and the Bureau of Prisons.

• Provide evaluative capabilities for federally funded drug programs operated at the federal, state and local levels.

• Maintain and monitor an ongoing collection of data necessary for present and prospective policy planning, including data on incidence, nature and consequences of drug use.

• Develop and implement a general directed research plan.

• Provide discretionary funds for those areas in which innovative and experimental programs are necessary at the local level and for other essential programs which cannot be adequately funded by the states.

• Direct the federal law enforcement response in the drug field and provide assistance to state law enforcement.

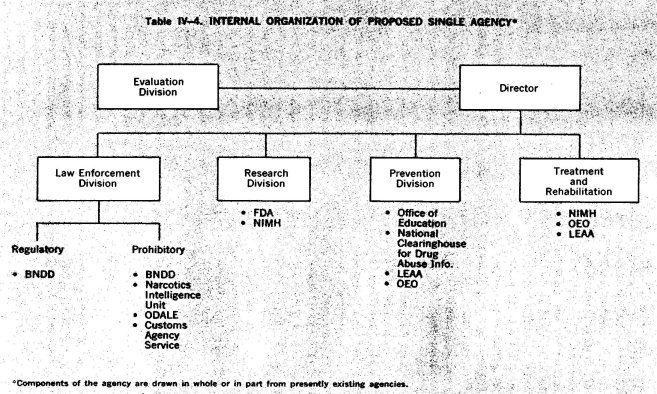

In assuming these tasks the agency will absorb the following functions and agencies. (See Table IV-4) :

• Those functions now assigned to the Special Action Office for Drug Abuse Prevention.

• All functions presently performed by the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs.

• Those parts of the Bureau of Customs, including the Customs Agency Service, which are involved in drug matters other than routine border inspections.

• The Office of National Narcotic Intelligence presently within the Department of Justice.

• The Office of Drug Abuse Law Enforcement of the Department of Justice.

• All functions now performed by the Division of Narcotic Addiction and Drug Abuse, National Institute of Mental Health.

• All drug-related functions that are performed by the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration or that are, or were, formerly performed by the Office of Economic Opportunity.

• All research functions related to psychoactive drugs and responsibilties under the Controlled Substances Act now performed by the Food and Drug Administration, other than those relating to the marketing of new drug products.

• All drug education and information functions now performed by the Office of Education.

• All drug abuse education and information functions performed by the National Clearinghouse for Drug Abuse Information.

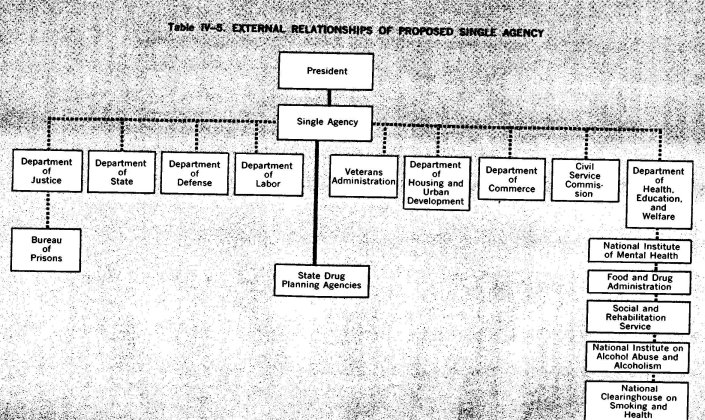

In addition, the Single Agency should maintain a close coordinating relationship with those agencies which perform drug-related funcions not incorporated into the Single Agency: (See Table IV-5)

• Department of Justice (includes Bureau of Prisons) .

• Department of Health, Education and Welfare (includes NIMH, SRS, FDA, NIAAA, and the National Clearinghouse on Smoking and Health) .

• Veterans Administration.

• Department of Defense.

• Department of State.

• Department of Housing and Urban Development.

• Department of Labor.

• Department of Commerce.

• Civil Service Commission.

The Commission feels that this structure will end the present fragnentation of effort and enable the government to operate more efficiently in providing the services promised to the states and local cornnunities (See Table IV-6). While a good organizational structure ;annot promise success, a poor one can assure failure.

Organization of Response at the Community Level

Preoccupation with the organization of the government response to drug use at federal and state levels sometimes obscures an obvious fact : it is at the community level that most treatment services will be provided, and that prevention will be achieved, if at all. Except for law enforcement efforts against major trafficking and except for what remains of experiments in institutional commitment of drug-dependent persons, all drug programs operate within the context of a community and through community institutions, both public and private.

Plainly, then, organization of the community response is as important as organization of the state and national response. The Commission, however, does not consider it appropriate to offer detailed organizational recommendations for the community level. We were able to make a long and close study of the federal organizational response since were were dealing with a single "national" problem at that level (Mushkin, et al., 1973) . Even at the state level, we only had to deal with a limited number of variations in the nature of the problem and the type of political structure (Booz-Allen, 1973). At these levels, too, the governmental role is primarily administrative and evaluative. At the local level, though, the matrix of political organizations and private institutions is as varied as the nature of the local drug problems. No structure we might fashion would fit even a substantial minority of communities; each locality must tailor a response to its own individual needs.

Nonetheless, a few elements of organization seem universal in their application. The Commission recommends that each community with a significant drug use problem have a coordinating council to insure communication and concert of action between the various drug-related functions in the community. Council membership should consist of representatives of the police department, drug treatment programs, education and counselling programs, and other interested local agencies, and a cross-section of the community (including the youth community) . The Council would not only foster cooperation among drug-related functions, but serve as a point of contact with state and federal agencies, and ensure a flow of information between the members of the community and all levels of government dealing with the drug problem 37

In addition to its other functions, the community council should also encourage and support local institutions in developing their own drug programs. Local functions should not merely be an extension of federal and state plans, no matter how much they may depend on federal and state funds. Earlier we pointed out that the federal government should not let communities define the national drug problem subjectively; now we emphasize that communities must not allow the higher levels of government to define their problem statistically. Àt the community level, objective analysis of the problem must be tempered by an intimate appreciation of local needs and idiosyncracies, and for this reason it is important that community institutions do not surrender all initiative to state and federal governments. The Commission emphasizes the need for local planning and local programs which are run by, and responsive to, the community they serve.

1 Private agencies have also entered the drug abuse funding business. The most notable is the recently created Drug Abuse Council, funded by private foundation monies.

2 See discussion by Blumstein, et al., (1973), in Appendix to the Report, critiquing present methods for estimating numbers of heroin-dependent persons.

3 Commissioners Hughes, Senator from Iowa, and Javits, Senator from New York, while concurring in some of the findings of the Commission with respect to the present lack of coordination and effort, do not concur in the recommendation that a single agency be created to house all federal activities in the areas of drug law enforcement on the one hand and, on the other, drug use prevention, that is, education, research, treatment, and rehabilitation.

First, during the 92nd Congress both Commissioners were members of the Senate Committees which together carefully examined the administrative problems entailed in developing a coherent federal response to the nationwide drug problem. The Congress and the President then agreed on the Drug Abuse Office and Treatment Act, signed in March, 1972, which provided the legislative foundation for the Special Action Office for Drug Abuse Prevention and directed it to lead in developing federal policy and to coordinate all federal prevention activities.

Several months passed before funds could be appropriated and the Special Action Office could become fully operational. Therefore, the administrative design provided by the Act has been tested for less than a full year. The Special Action Office has faced a most difficult and complex task, and it would be a rare situation indeed if it were not without some problems. But its performance in carrying out its statutory responsibilities must be carefully reviewed by the appropriate committees of Congress in the proper exercise of their responsibility for legislative oversight. In this respect, both Commissioners agree with the recommendation that Congressional Committees undertake an in depth review of the situation. Commissioners Hughes and Javits believe that it is premature to conclude that the design has failed and must be replaced with a new federal agency.

Second, based on their experience in government, at both the state and the federal levels and in both executive and legislative positions, the Commissioners are not now convinced that it is wise to place within one agency functions which are for the most part entirely unrelated and which must be carried out by officials with widely differing training and perspectives. Placing these activities and personnel within one agency might well create more serious problems than those which the proposal is intended to solve. For example, the most difficult task would be the selection of a director who could maintain a steady course while successfully resisting undue pressures from either group. The presence of both sides within the agency could in itself create temptations to compete for dominance on matters of policy. It would perhaps be unrealistic to expect one man to preside over such disparate interests.

Third, Commissioners Javits and Hughes are not persuaded that the Commission has identified major problems of coordination between law enforcement and prevention agencies that require a single agency for their solution. The primary problems of duplication and lack of coordination arise between agencies carrying on similar or closely related activities. The Customs Bureau and the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs have frequently disagreed, and there have been failures of coordination among treatment activities funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, the Office of Economic Opportunity, and the Model Cities programs of the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

As between law enforcement and prevention agencies, the administrative problems most commonly occurring stem from the fact that some of the law enforcement agencies support treatment activities, which are somewhat peripheral to the primary tasks of these agencies. Such activities could be transferred to the prevention- agencies.

Finally, while fully sharing the Commission's interest in improving the governmental response to the drug problem, both Commissioners believe that the Commission's analyses do not support the conclusion that a single agency would best serve that goal. The Commission's studies have identified many real problems, but there has been no thorough examination of either the advantages or the disadvantages of a single agency. This can best be done by the Congressional Committees with jurisdiction over these matters.

4 See footnote 35 pp. 291-292.

5 Where local government is tiered—for example, where community governmental functions are divided between county and municipal governments—the larger unit might also establish a coordinating council, composed of representatives from the community councils and from county government agencies.