| - |

Drug Abuse

Chapter two

Drug-using behavior in the United States

Drug-using behavior is rooted in a complex array of psychological, biological, social and economic conditions and circumstances. As the now ebUndant research literature demonstrates, drug use varies according to the year during which an investigation is undertaken, the social and demographic characterise of the population under study, the symbolic, individual and social meanings which are attached to particular kinds of drug use, and the nature of extent (incidence, prevalence and patterns) of drug use in the population being observed.

Despite the multifaceted nature of drug-using behavior, large segments of both the lay and professional public have traditionally perceived drug use as a unitary phenomenon. This is reflected in the fact that over the years, social concern about "drug abuse" has been expressed not in terms of the quality but of the quantity of the disapproved behavior. On the other hand, the descriptive terminolog, employed in both common parlance and the research literature has more to do with the individual who has engaged in this behavior than it does with the behavior itself. Terms such as "dope fiend," "junkie" and "addict," have come to symbolize or describe the attributes and characteristics of drug-using individuals. Such terms have been indiscriminately applied to behaviors ranging from the one-time use of marihuana to the regular and chronic use of heroin.

This Chapter focuses on drug-using behavior in the context of individual and institutional (social) supports and deterrents. It describes more precisely recent trends in the incidence, prevalence, patterns, conditions and circumstances of drug-using behavior and identifies more precisely the major classes or types of drug-using behavior.

Before analyzing these data, a note of caution is necessary relative to the use of these data for policy making. In recent years, social and behavioral scientists have made gains in assessing the nature and extent of a number of serious social problems, including drug use, crime, delinquency, poverty, illegitimacy and mental illness. The measurement of social data has become increasingly more precise and sophisticated, and statistics of all types have burgeoned. One of the unintended and unfortunate consequences of these advances has been the tendency of policy makers to appropriate these statistics, often taking them out of context, and to convert them directly into public policy decisions. Little or no attention is given to the assumptions and hypotheses suggested by the findings or to the limitations, reliability and validity of the data.

Policy making should be regarded as a process, only the first step of which is to provide the data base. Survey findings regarding drug-using behavior provide descriptions of who uses drugs of what type and to what extent. They do not, however, address the motivations for drug use or the possible consequences that given types and patterns of drug use pose for both the individual and the larger society. Consequently, this Chapter focuses on the nature of drug-using behavior. In Chapter Three, we will assess the individual and social consequences of drug use.

1 DRUG USE IN THE GENERAL POPULATION

Chemically induced mood alteration is taken for granted and is generally acceptable in contemporary America. The degree of acceptability, however, is defined by the source and type of substance taken as well as certain characteristics of the individual, such as age and socio-economic status.

This society is not opposed to all drug taking but only to certain forms of drug use by certain persons. Self-medication by a housewife or a businessman with amphetamines or tranquilizers, for example, is generally viewed as a personal judgment of little concern to the larger community. On the other hand, use of such drugs by a college student or other young person to stay awake for studying or simply to experience the effect of such drugs, is ordinarily considered a matter of intense community concern extending even to legal intervention.

This variation in the acceptability of drug-using behavior is regarded by many young people as hypocritical. The Commission recognizes that contemporary social attitudes are indeed inconsistent, reflecting the special status which this society accords its youth as well as the general confusion regarding what is a drug and what constitutes "drug abuse." For this reason, the first part of this Chapter is devoted to drug consumption within the total population, most of which is not ordinarily characterized as "drug abuse."

The most widely used mood-altering drug in America is alcohol. Retail sales of alcohol (wine, beer and hard liquor) in 1971 amounted to $24.2 billion and sales have increased nearly $7 billion in the five-year period from 1966 to 1971. Put another way, Americans consumed almost four and one-half billion gallons of beer, wine and distilled spirits in 1971, a record high for American alcohol consumption. Between 1947 and 1971, the per capita consumption in gallons of beer, wine and distilled spirits among persons of drinking age increased from 27.15 gallons to 30.6 gallons.

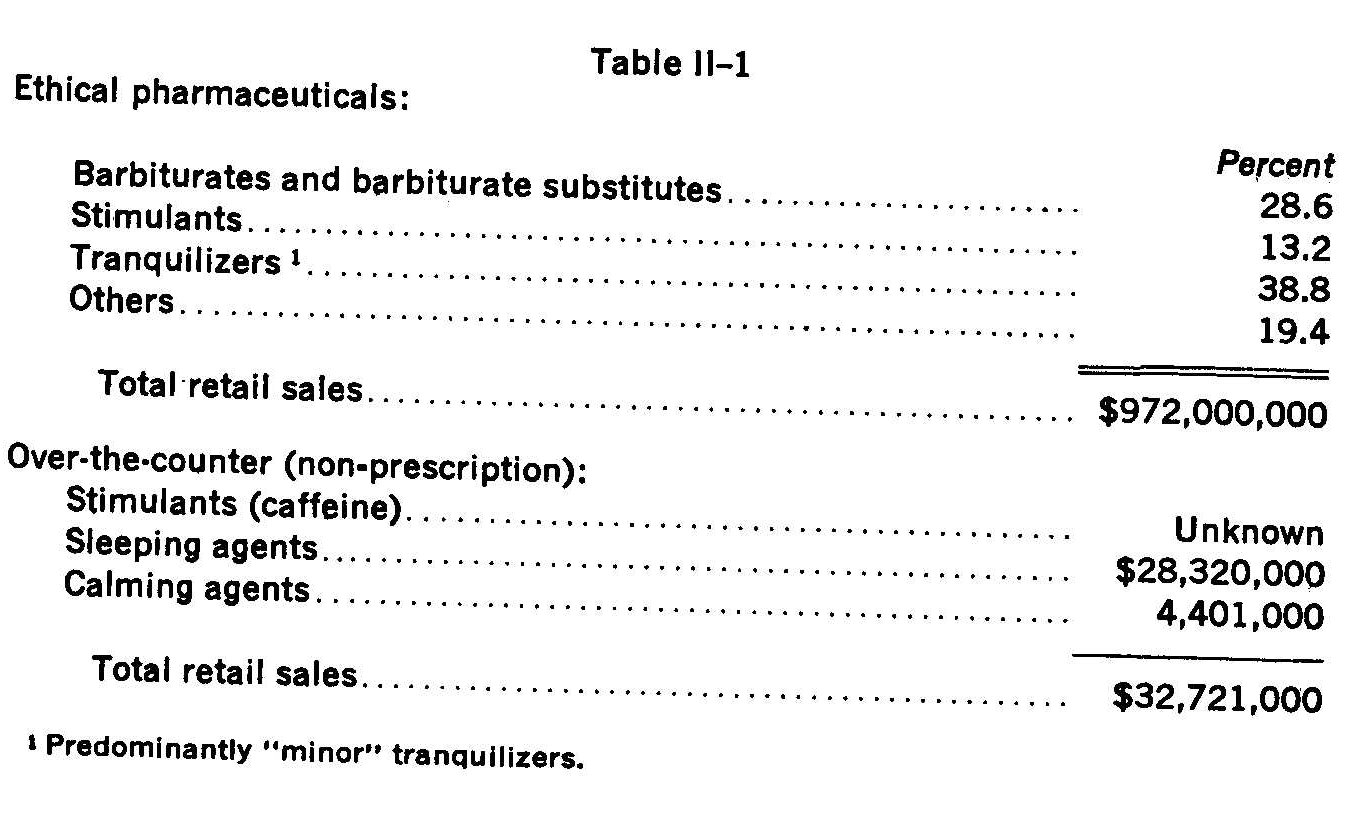

In 1970, barbiturates and barbiturate substitutes accounted for 28.6% of the 214 million prescriptions issued for psychoactive drugs. Anti-anxiety agents, the so-called "minor" transquilizers, accounted for almost 39%. Prescriptions for stimulants (13.2%), anti-psychotics (10.2%), and anti-depressants (9%) made up the rest of the total, which represented altogether an estimated $972 million in retail sales (Baiter and Levine, 1971).

At the same time, Americans were also obtaining large quantities of over-the-counter (non-prescription) mood-altering agents. In 1970, proprietary sales totalled $28,320,000 worth of sleeping agents, $4,401,000 worth of tranquilizing agents and a substantial, though unknown amount of caffeine stimulants. (See Table II-1.)

Although distributors do not maintain records on the age of persons who purchase either by prescription or over-the-counter, information presently available indicates that the greatest proportion of such items was purchased and consumed by persons over 21. The same is certainly true with respect to the sale and use of alcoholic beverages.

In an effort to assess more precisely the nature and extent of drug use in the American population, the Commission sponsored a national household survey of youth (12 to 17 years) and adults (18 years and over). By means of self-administered questionnaires, respondents anonymously indicated the incidence (ever use), prevalence (current use) and patterns (frequency, intensity, duration and amount) of their drug-using behavior. The questionnaire elicited information on the use of the most common mood-altering substances (tobacco and alcohol), as well as to controlled pharmaceuticals (proprietary and ethical sedatives, tranquilizers and stimulants), and a number of illict mood-altering drugs such as marihuana, LSD, cocaine and heroin.

The Survey findings indicate that substantial segments of our youth and adult population have had some experience with mood-changing drugs but that the incidence, prevalence and patterns of use vary significantly according to a number of important individual and social factors. Before discussing the characteristics of individuals who use drugs of different types and the individual, social and cultural influences which bear upon drug use, it is appropriate to describe the nature and patterns of drug use which emerged from our survey data.

TOBACCO AND ALCOHOL

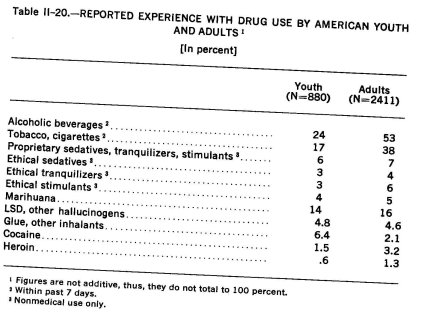

The Commission's National Survey data show that 38% of the adults and 17% of the youth in this nation currently smoke cigarettes and that about half of the adults (53%) and one-fourth of the youth (24%) had consumed either beer, wine or liquor within the week prior to the Survey.

Although, as indicated earlier, the vast majority of respondents did not regard either tobacco or alcohol as drugs, a significant relationship was found to exist between the consumption of these substances and the use of other types of drugs. About one-half of the adults who admitted to having used "medical" drugs for non-medical reasons (53%), to having consumed alcohol (47%), and to having had some experience with marihuana (56%) were current smokers. Similarly, 86% of the adults and 63% of the youth who had tried marihuana reported consuming alcohol within the seven days prior to the Survey.

Both tobacco and alcohol provide striking contrasts to most other forms of drug-using behavior, relative to the frequency, intensity, duration and amount of use. In brief, cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption are significantly more likely to start earlier and last longer than other types of drug use; and a significantly greater percentage of those who have experience with these drugs progress or escalate to more frequent, more intense and heavier tobacco and alcohol use patterns as they grow from pre-adolescence to adulthood.

Although 5% of the youth reported smoking at least one pack of cigarettes a day, five times as many adults (25%) said they did so. Similarly, with respect to alcohol, one-fifth (20%) of the adults remember having first tried an alcoholic beverage at age ten or younger. Among today's youth, twice that proportion (40%) reported consuming alcohol prior to their eleventh birthday; however, awareness of the mood-changing properties of alcohol and the adoption of "social drinking" patterns do not generally occur until the teen years.

Beer is the type of alcoholic beverage currently consumed with greatest frequency by both youth and adults (17% and 38%, respectively). The consumption of hard liquor, however, reveals a different picture. One-half of all adults who reported consumption of alcohol within the week prior to the Survey consumed liquor (as opposed to beer or wine), but only one-fourth of the alcohol-using young people drank hard liquor.

Although most adults report light to moderate consumption of liquor and wine (up to five glasses a week) , a considerable segment of the adult drinking population, roughly one-fourth, are heavier drinkers (more than six drinks in seven days). Among young people, use of wine and liquor tends to be rather light while the frequency of beer drinking is rather evenly distributed.

In terms of the quantity of alcohol consumed at any given time, the data show that on any one day, "light drinking" (one or two drinks on any one day) is the modal behavior pattern for use of the three types of alcoholic beverages in both age groups.

We have already noted the significant relationship between the consumption of alcohol and the use of other classes of drugs. The Survey data further show that the use of alcohol does not always occur by itself; a considerable segment of our population, particularly our young adults (18 to 25 years), use alcohol in combination with other drugs such as stimulants or sedatives, thereby potentiating the effects of both and significantly increasing the risk of individual and social harm. While the use of tobacco and alcohol cannot be said to lead to other types of drug use, this behavior can be viewed as a precursor to and a fairly accurate predictor of other types of drug-using behavior.

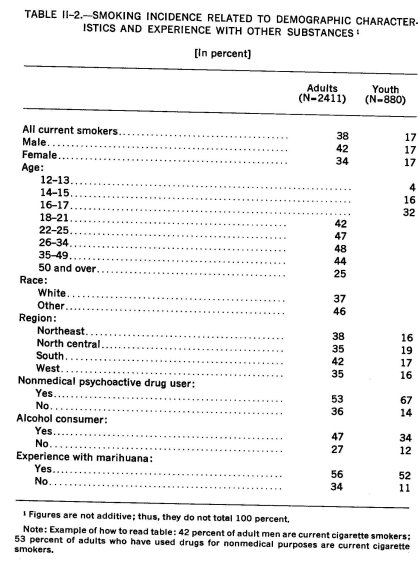

With respect to cigarette consumption, the most substantial differences in smoking incidence among both youth and adults are found not in demographic attributes, but in other kinds of drug consumption.

The Commission's National Survey found that cigarette consumption is more frequently associated with the reported use of alcoholic beverages, marihuana or prescription drugs than it is with any one of the social or demographic characteristics of the users. (See Table 11The Commission's National Survey found that cigarette consumption is more frequently associated with the reported use of alcoholic beverages, marihuana or prescription drugs than it is with any one of the social or demographic characteristics of the users. (See Table

11-2.)

As Table 11-2 shows, cigarette smoking increases with age until it reaches a peak of nearly half the population in the 26-34 age bracket and decreases after that time. Although there are no differences by sex among young smokers, higher proportions of men than women are current cigarette smokers. The data also reveal a somewhat higher percentage of cigarette consumption among the non-white than the white population. Observable, too, among adults is a greater reported incidence of cigarette smoking among people who live in the South or in metropolitan areas than among those residing in other geographic sectors or in rural areas. In sum, the Commission's National Survey data show that 53.114,000 adults and 4,234,000 youth currently smoke cigarettes.1

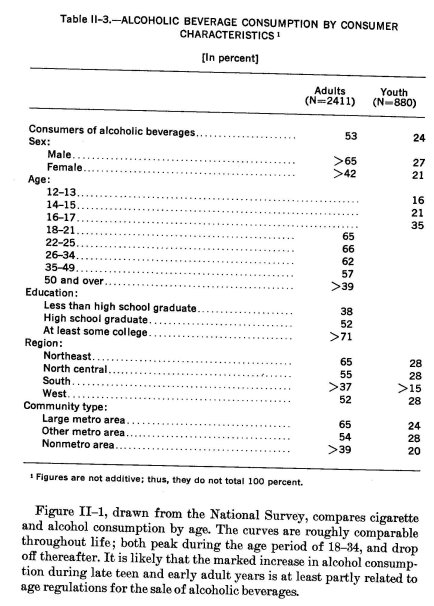

As shown in Table 11-3, 53% or 74,080,000 adults 18 years and over, and 24% or 5,977,000 youth 12 to 17 years of age had consumed some type of alcoholic beverage within the week prior to the survey.'

Numerous social and demographic differences exist with respect to alcohol consumption. On the variable of sex, males, both adult and youth, are considerably more likely than females to be alcohol consumers. With regard to age, use begins its steep climb during the middle teens, reaches its high point (66%) in the 22-25-year age group and gradually levels off thereafter to about 39% of the 50 years and over age group.

Alcohol consumption also increases with years of formal education; only 38% of adults with some high school education as compared with more than 71% of those with some college education had consumed alcohol within the past week.

The highest proportion of adult consumers resides in the Northeast (65%) and the lowest proportion (37%) live in the South. Among youth, consumers are more equally distributed throughout the country, but again the smallest proportion is found in the South (15%). In both age groups, consumption is more prevalent in metropolitan than rural areas but the differences according to community type are not as pronounced among youth as they are for the adult population. (See Table 11-3.)

Based upon U.S. Census data projections as of July 1, 1972.

The "past seven days" was arbitrarily established to define "use" because it provides more reliable data on consumption of beer, wine and liquor than does a longer reporting period.

USE OF PROPRIETARY AND ETHICAL PSYCHOACTIVIE SUBSTANCES

Lack of public familiarity with the names of ethical and proprietar drugs and the generally sporadic nature of their use inhibit the corn pilation of reliable and valid survey data. The Commission's Nationa Survey sought to overcome these problems in two ways. First, re spondents were aided in their recall by four cards specifically intender to illustrate the most well known and widely used of the proprietar and ethical sedatives, tranquilizers and stimulants. Secondly, the Sur vey gathered both incidence (ever use) and prevalence (use within the past year) data. These data were then related to the reasons for use in order to provide a more accurate picture of the meaning of the incidence and prevalence data.

Incidence and Prevalence

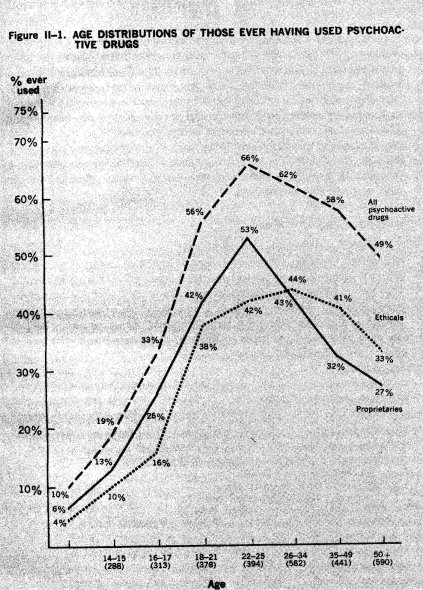

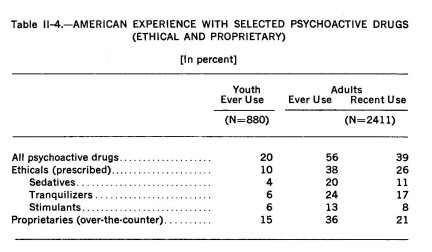

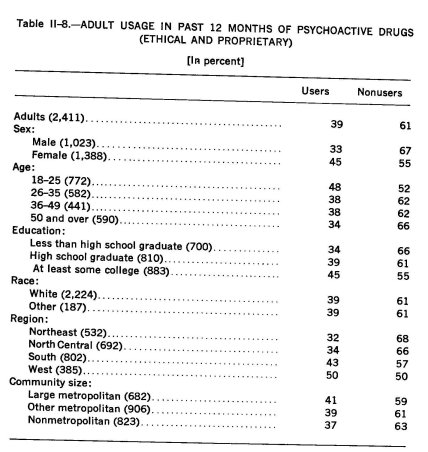

The National Survey data show that more than half (56%) of all adults and one-fifth (20%) of all youth have had experience with one or more proprietary or ethical sedatives, tranquilizers or stimulants.3 The extent of current use can be roughly estimated from figures regarding recent (within the past 12 months) use of these substances among adults. The data show that 39% of all adults or about 70% of the ever users have used one or more of these substances within that time. (See Table 11-4.)

8 The following substances are included in the National Survey classifications: Ethical (prescription) drugs

"Sedatives" : Nembutal, ® Seconal,® Butisal,® Buticaps,® Doriden,® Tuinal,® Noludar,® Carbrital,® Phenobarbital.

"Tranquilizers": Miltown,® Meprospan,® Meprotabs,® Librium, ® Libritabs,® Equanil,® Valium, Serax,® Atarax,® Vistaril.®

"Stimulants": Dexamyl,® Tenuate,® Tepanil,® Eskatrol,® Bamadex,® Ambar,® Pre-sate, ® Ritalin.®

Proprietary (Over-the-counter) drugs

"Sedatives": Nytol,® Sominex,® Sleep-Eze.®

"Tranquilizers": Compoz,® Cope, Nervine.®

"Stimulants": No-Doz, Vivarin,® No Nod, Caffeine Tablets.

Substantial overlap exists among adult users of the various classes of ethical drugs. About one-half of the sedative users, for example, have also used tranquilizers while about one-third have used stimulants. Similarly, among stimulant users, about 40% have used tranquilizers and also about 40% have used sedatives. Among the ethical drugs, tranquilizers have been used by the greatest number of adults. Forty percent of the tranquilizer users have also used sedatives and about one-fourth have used stimulants. Four percent of the adult population have used all three types of ethical psychoactive drugs.

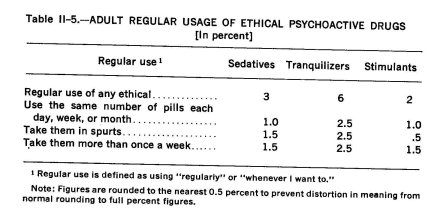

These figures, however, tell us nothing about either the frequency, the regularity or the purposes of use. With respect to the former, the absolute number of regular users of these drugs among both youth and adults is too small to permit meaningful analysis of these subgroups. Table 11-5 indicates the frequency and regularity with which adult recent users (within the past 12 months) have consumed ethical sedatives, tranquilizers and stimulants.

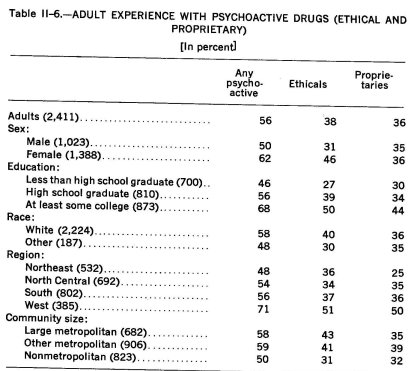

Demographic Characteristics

Experience with sedatives, tranquilizers and stimulants, both ethical and proprietary, was found to be higher among Whites than among other racial groups, among women than men, among persons reporting more formal education, among those residing in metropolitan as opposed to rural areas, and among those persons residing in the West. (See Table 11-6.)

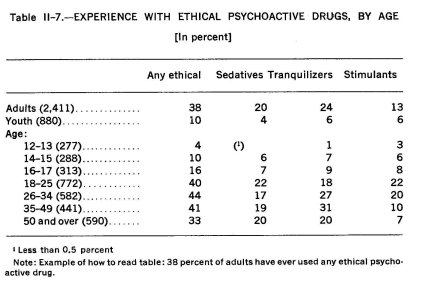

The data also show that considerable differences exist in the patterns of consumption, by age, among the three classes of ethical drugs. (See Table 11-7)

As Table II-7 illustrates, sedative experience is pretty well independent of age; tranquilizers are used most extensively by the middle-aged ; and stimulants have been used most heavily by younger adults.

With respect to recent usage of these drugs, age and education again play significant roles in differentiating usage patterns. Region is also important, as is indicated by the fact that half of all adults in the West have used at least one of these drugs in the past year. (See Table II-8)

From Table 11-8, we can also obtain a picture of the non-user. In general terms, he is more likely to have less than a high school education, be older than 50, and live in the Northeast or North Central regions of the United States.

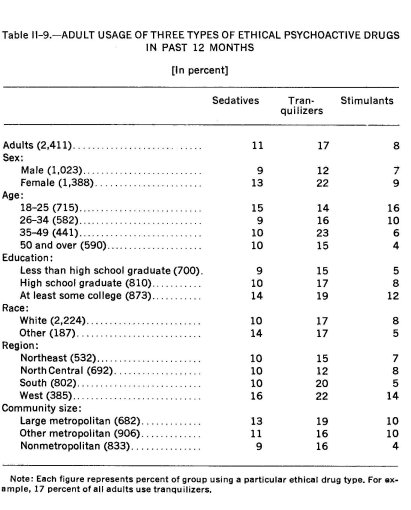

The National Survey data show that those persons who have used ethical psychoactive drugs within the last year vary considerably by the type of drug (See Table 11-9). Some patterns, however, hold for all three types. Women are more likely than men to use any of these drugs, and such use is also highest among those with college training, living in larger communities and residing in the West.

Usage patterns by age differ according to the type of drug. Younger adults are more likely to use stimulants and somewhat more likely to use sedatives, but it is the 35-49-year-olds who are most likely to use tranquilizers (See Table 11-9) .

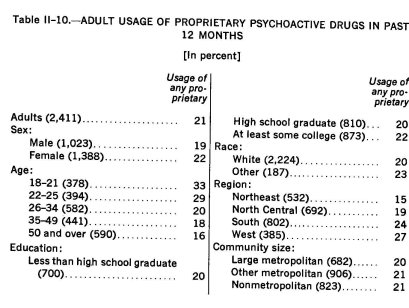

As Table II-10 illustrates, the usage of proprietary drugs, in contrast to the ethical psychoactive drugs, is correlated strongly with only two of the demographic variables (age and region). Education, sex, community size and race were found to have only a minor impact on degree of usage.

Motivations for Use

In an effort to determine more precisely the reasons for use of these substances, recent users were presented with a list of five statements describing various possible non-medical uses. These were :

"Have you ever taken these pills ..."

a. "To help get along with your family or other people."

b. "To help you get ready for some big event or to help you accomplish something."

c. "Just to see what it was like and how it would work."

d. "Before going out so that you could enjoy yourself more with other people."

e. "Just to enjoy the feeling they give you."

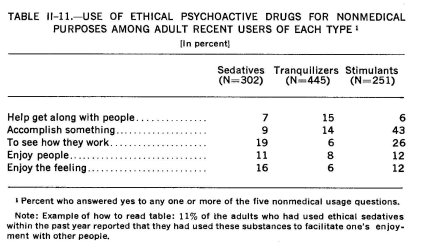

Table II-11 presents the proportion of adult recent users of ethical psychoactive drugs who responded affirmatively to each of the five non-medical use statements. The data show that the preponderant use of sedatives is for experimentation and enjoyment, that tranquilizers are used more often as coping mechanisms and that the primary uses of stimulants are for the more specific purpose of accomplishing something or just to see how they work.

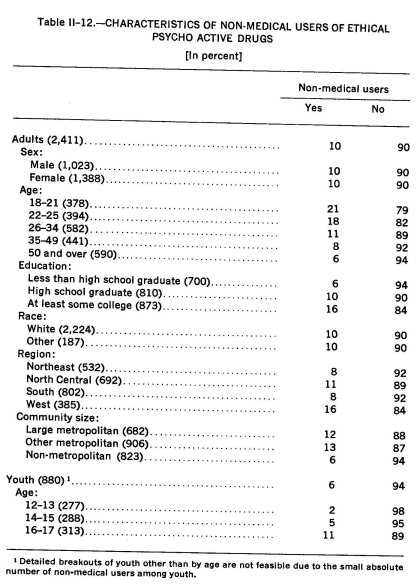

Table 11-12 presents a profile of all respondents who indicated non-medical use of ethical psychoactive drugs within the past year. As the data indicate, non-medical use rises through the teens, peaks in the young adult years, then drops continuously with increasing age. Although education was found to be associated with non-medical usage, race and sex failed to emerge as significant variables. Usage was found, generally, to be higher among those living in the West and in metropolitan areas than among those living elsewhere.

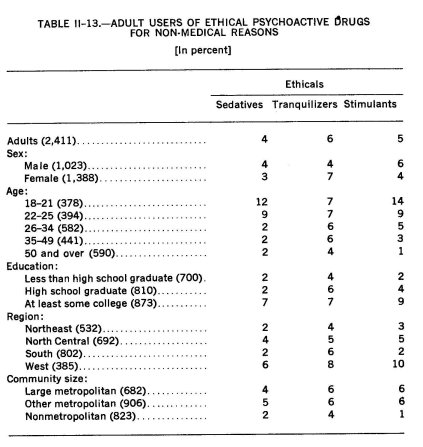

Table 11-13 shows non-medical users by type of ethical psychoactive drug. As the data show, adults differ in their characteristics according to the type of ethical drug used. Non-medical usage of stimulants, for example, ranges from 1% of those over 50 years of age to 14% of those 18-21 years old. The corresponding variation among tranquilizer users is from 4% to 7%.

In sum, 10% of the adult population has used ethical psychoactive drugs for non-medical purposes : 4% have used sedatives, 6% have used tranquilizers and 5% have used stimulants in this fashion. These figures represent 39% of the adult recent users of all ethical drugs. Likewise, 6% of the youth or 60% of those with any ethical drug experience have used these drugs for non-medical purposes.

Multi-Drug Use

Alcohol, Ethical and Proprietary Psychoactive Drugs

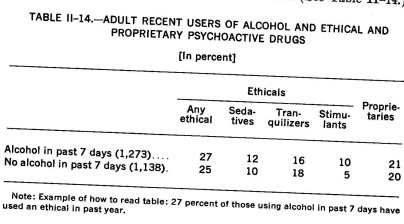

The Commission's National Survey found that among adults, only a marginal relationship exists between consumption of alcoholic beverages and recent use of ethical or proprietary psychoactive drugs. Except for a somewhat higher incidence of stimulant use, consumers of alcohol have about the same pattern of recent pill usage as those who have not used alcohol within the last week. (See Table 11-14.)

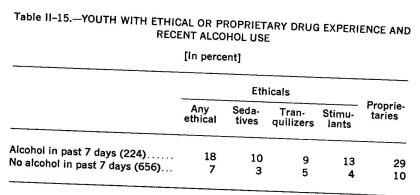

Among youth, the data show a different relationship. Young people who are recent alcohol consumers are more likely than non-consumers to report ever having had experience with these ethical and proprietary drugs, regardless of the particular type of drug. (See Table 11-15)

Marihuana and Ethical and Proprietary Psychoactive Drugs

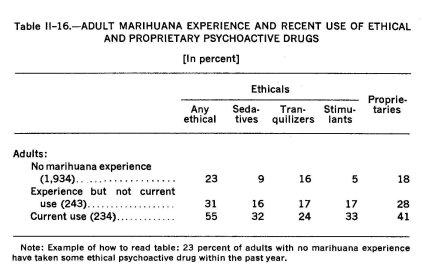

In contrast to alcohol, experience with marihuana is significantly associated with use of both ethical and proprietary psychoactive drugs. Table 11-16 shows the proportion of adults with and without marihuana experience who have used each class of ethical and proprietary drugs within the past year.

Pill usage is positively associated with marihuana experience. Moreover, among adults, current marihuana users are more likely to be recent pill users than are persons who have had marihuana experience but are not current users of marihuana.

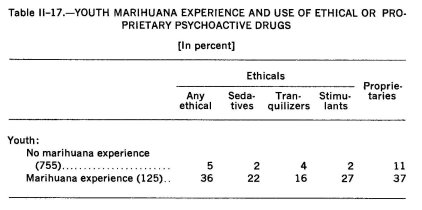

Among youth (12 to 17-year-olds), pill experience and marihuana experience are also positively correlated. (See Table 11-17)

Concurrent Drug Usage

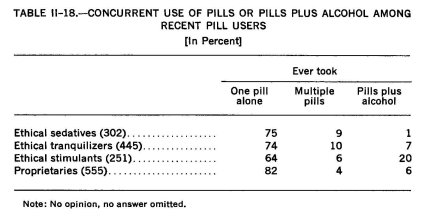

The Commission's National Survey data show that a minority of recent adult users of ethical psychoactive drugs has used several pills concurrently or has used a pill in combination with alcohol. Table II-18 presents the data concerning concurrent multi-drug use 4 among adults who have recent experience with each type of ethical or proprietary psychoactive drug.

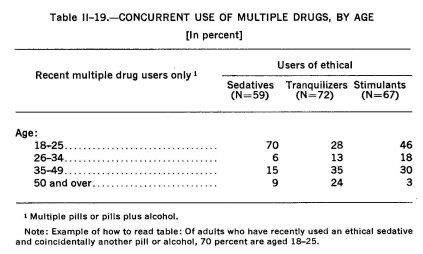

Only a limited amount of subgroup analysis is possible due to the small numbers of recent users who have concurrently used more than one pill or who have used a pill plus alcohol. Table 11-19 shows concurrent use by age.

Despite the small bases, the concentration of concurrent use of sedatives and another pill or alcohol among those 18-25 years of age is statistically meaningful. Young people in this age group were also substantially overrepresented among those who use stimulants concurrently with another drug, although because of the small base size, care must be taken in interpreting these latter data.

Multiple drug use is not intended to imply that usage is only non-medical or that it applies only to pills illicitly obtained.

ILLICIT DRUG USE IN THE GENERAL POPULATION

Although the use of illicit drugs tends to arouse the greatest public clamor and concern, it is, with the exception of marihuana use, a relatively uncommon occurrence when measured against other types of drug experience. Table 11-20 presents in summary fashion the Commission's Survey findings regarding the reported drug experiences of American youth and adults.

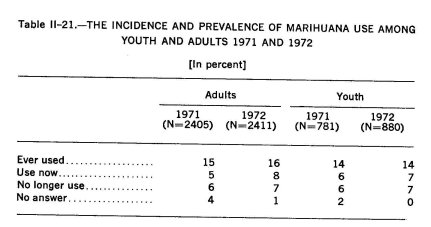

Marihuana

As indicated in Table 11-21, neither the incidence nor the prevalence of marihuana use has shown any significant increase, for either youth or adults, between 1971 and 1972. The figures suggest, however, that idults exhibited a somewhat greater tendency to continue smoking n 1972 than they did in 1971 while among youth small increases )ccurred in both the proportions who continued to smoke and those vho had terminated use.

Overall, the 1971-72 National Survey data regarding marihuana provide support for the Commission's speculation in the first Report that use may have reached its peak and begun levelling off ; no significant increases were found in either the incidence, prevalence or patterns of marihuana use (frequency and intensity), and when use did occur, it tended to be of an experimental or occasional (once a month or less) nature.

This conclusion draws additional support from another item designed to serve as a rough gauge of the potential for future use. In each of the two survey years respondents were asked to indicate what they would do if marihuana were legal and available. The data indicate that a small proportion of the non-using adults (3% ) and a somewhat larger proportion of the non-using youth (8%) would try marihuana under these conditions. For both age groups, however, these proportions are smaller than those of the previous year (adults: 4% to 3%; youth 12% to 8%). About equal proportions of youth (8%) and adults (9%) report they would use it at least as often as they do now. In sum, the prospect of readily available marihuana elicits no substantial expectation of initiated or increased consumption.

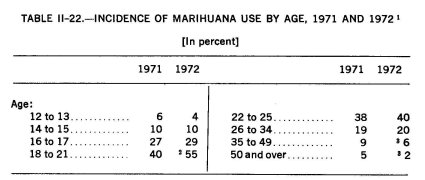

Experience with marihuana continues to be an age-related phenomenon quite similar to that which the Commission observed in its first year Report. Despite a large increase in incidence of ever-use in the 18-21 age group, ( +15%), the National Survey found that there has been no significant overall increase in incidence or prevalence of marihuana use among the American adult or youth populations as a whole. (See Table 11-22)

I Example of how to read table: six percent of the 12 to 13 age group reported experience with marihuana in the 1971 study. Figures are not additive; thus, they do not total 100 percent.

The Commission suggests that the disproportionate increase in the 18 to 21 year age group can be accounted for in the following three ways. First, a significantly large number of young people entering into this age group have already had experience with marihuana. Second, as the practice of marihuana smoking has become more widely distributed and commonplace, a significant number of 18 to 21-year-olds, particularly if they are students, are likely to be willing to try marihuana, primarily because they are more likely to know someone or to have friends who use it. Third, public tolerance of the use of the drug seems to have increased with the extent of use so that individuals may be willing to admit marihuana experience who would have been disinclined to do so in the past.

3 Because the Survey asked about any experience with marihuana (ever tried), the age data for older people should be cumulative. That is, if nine percent of the 35 to 49 age group reported such experience in 1971, we would expect at least the same proportion to report experience in 1972. However, in the two oldest age categories we find procedural inconsist- encies. We think that these may be accounted for in two ways. First, some of the difference may be attributed to sampling variability between the two studies. Second, the difference in interview context between 1971 and 1972 might also have had its effect, particularly in this age group. The 19.71 study focused almost entirely on marihuana, and thus may have better desensitized older respondents so that they felt comfortable in reporting on their experience. In 1972, before the questions on marihuana usage, respondents were taken through a lengthy battery of questions on experience with the ethical and proprietary drugs. Reporting on usage of these drugs may have increased resistence to reporting on other substances. One suggestion for a "best" estimate of usage within these older age groups would be to pick a midpoint between the figures for 1971 and 1972.

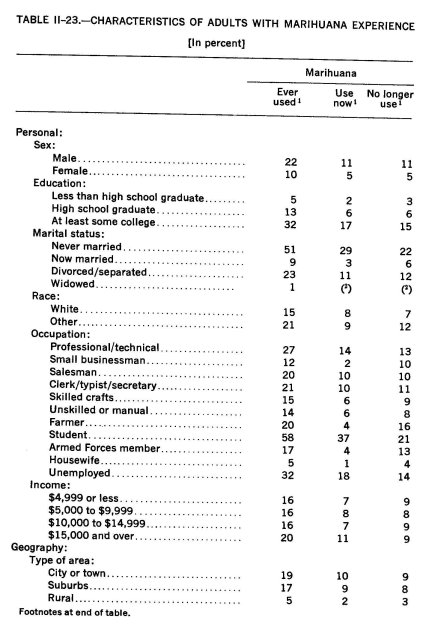

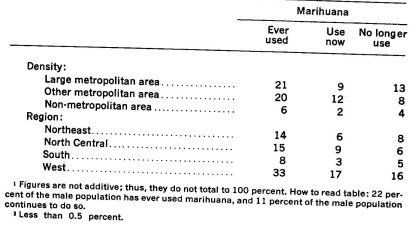

Table 11-23 shows that adult experience with marihuana is disproportionately higher among men than women, increases with years of formal education among adults and is higher among those who have never been married or are divorced or separated than among persons currently married. Marihuana experience is more often found among students than among other occupational groups and is proportionately higher among those with higher incomes. The National 'Survey also found that marihuana experience continues to be significantly higher in metropolitan than in rural areas and is disproportionately found among adults living in the Western states.

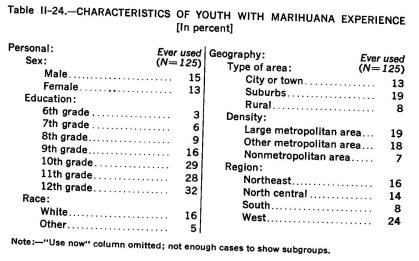

With respect to marihuana experience among youth, the National Survey findings in Table II-24 reveal little difference in marihuana-using experience between males and females. However, experience is as much an age-related phenomenon among youth as it is among adults. The data show a significantly higher proportion of marihuana experience among white than among non-white youth, and among residents of metropolitan or urban than among rural residents. Regionally, the highest incidence of youthful marihuana use is found in the West.

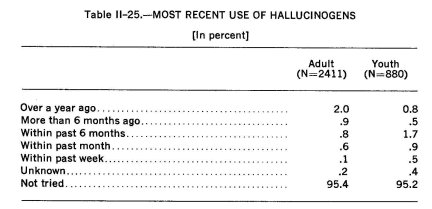

LSD, Other Hallucinogens

Among youth and adults, less than one in 20 (4.8% and 4.6% respectively) report having tried LSD or a similar hallucinogen at least once, although 24% of the adults and 29% of the youth report knowing someone who has used them. Among adults with hallucinogen experience, 60% reported their most recent use was more than six months ago; youth, however, tend to report more recent use and about 70% reported use within the past six months. (See Table 11-25.)

In order to gauge the potential for LSD use in the future, all respondents were asked what they would probably do if drugs of this type became legal and available. Only 1.2% of the adults and 2.5% of the youth said they would probably try it under conditions of legality and availability. Further, those who reported no experience with LSD were also asked if they would like to try it or a similar drug "once to see what it is like." Less than .5% of either age group said they would very much like to see what these drugs were like; another 2% of adults and 4% of the youth said they might try it, but they were not sure.

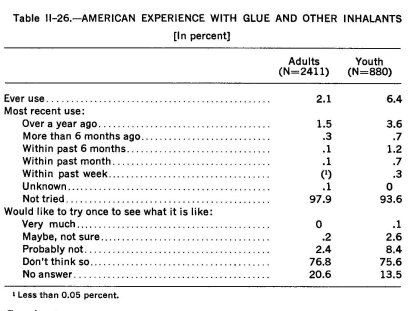

Glue, Other Inhalants

The inhalation of glue or other vapors is essentially a youth phenomenon which, for the most part, seems to have passed its peak. Among the adult population, 2% have reported some experience with inhalants, most of it occurring more than one year ago. Six percent of the youth, however, have tried inhalants at least once, and among those with experience, two-thirds (4%) report their most recent experience with these substances was more than a year ago. None of the adults and .1% of the youth who have never tried inhalants indicated that they would definitely like to try them in the future. (See Table 11-26.)

Cocaine 5

Although less widely available and more expensive than heroin, somewhat larger proportions of both youth and adults report experience with cocaine than with heroin, but the differences are not statistically significant. Three percent of the adults and 1.5% of the youth report that they have tried cocaine at least once, and an additional 2% of the adults and 5% of the youth without cocaine experience indicated that they might like to try this drug in the future. One percent of the adults and 3% of the youth said they would probably try it if cocaine were legal and available.

Heroin 5

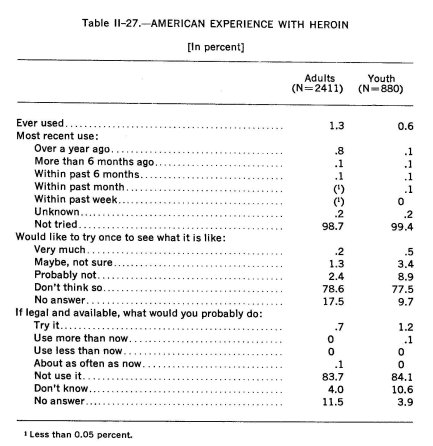

Heroin was found by the Commission's National Survey to have the lowest reported rate of incidence of all drugs included in this study. 1.3% of the adults and .6% of the youth reported that they had tried heroin at least once although 20% of the former and 21% of the latter claimed to know someone who has used heroin.

Of those who had never tried heroin, slightly more than 1% of the adults and 3% of the youth indicated that they might like to try heroin at some time just to see what it was like. Even if legal and available, only about 1% of both groups said they would try it. (See Table 11-27.)

5 The Commission emphasizes that household surveys do not generally pick up "street" users of cocaine and heroin and therefore underestimate both the incidence and prevalence of such use.

Multi-Drug Use

Youth and adults who try and use LSD, cocaine or heroin are most likely to be found in the group of persons who regularly smoke cigarettes, are regular consumers of alcohol (used within the last week), have some experience with marihuana, and use ethical psychoactive drugs (and alcohol) for self-defined non-medical purposes such as coping with stress.

The Commission wishes to point out, however, that the existence of this association between the use of these three drugs (LSD, cocaine and heroin) and the use of other drugs should not be taken to mean a causal link. The Commission has found no evidence, either in its review of the research literature or the studies it has conducted, to support the theory of a causal relationship. What the data do demonstrate, however, is that there is an identifiable segment of our population which uses various drugs, either singly or in combination, for varying reasons, ranging from curiosity and recreation to coping with stress. The use of no specific drug, however, inevitably leads to the use of any other drug, although there may be a non-specific process of conditioning to the psychological reinforcements of drug experiences.

II DRUG USE AMONG STUDENTS

Up to this point, the data we have presented were drawn exclusively from the Commission's National Survey of American youth and adults relative to their drug-using experiences and related attitudes and behavior.

Many of the findings emphasize the fact that most Americans, when thinking about drug use tend to associate it in some important ways with youth. Indeed, almost half of the people (49%) who expressed a definite concern about drugs as one of the two or three most serious problems facing our nation today see drugs specifically as a problem of the young.

Due to the mounting public concern over the increase in the incidence of student drug use from the college campus down to the junior high (and occasionally elementary) school, the Commission decided to devote a segment of this Report to the phenomenon of student drug use at the secondary school and college levels.

During the past two years, the Commission made a concerted effort to obtain all of the student surveys undertaken throughout the country from 1965 to the present and has developed a file of more than 200 student surveys. The more than 900,000 student respondents represented in these surveys constitute figures corresponding to about 3% of this nation's junior and senior high school students, about 2% of American college undergraduates and approximately 2% of all young Americans between 12 and 21 years of age.

SURVEY METHODOLOGY

Before proceeding with our analysis of the survey incidence data, a brief explanatory note relative to sampling and statistics is necessary. Undoubtedly, the basic question is the extent to which statistics drawn from any sub-segment of a population are generalizable to and representative of the total population under study. By definition, a sample represents only a small part of a larger aggregate or universe (secondary school or college students, for example) about which information is sought, and the data collected in surveys of selected samples are subject to bias and variation ; consequently, the estimates are imprecise in absolute terms and may vary in reliability s and validity,7 both of which are statistically measurable and dependent upon proper sampling techniques.

The reader will note that the composite incidence figures drawn from the student surveys sometimes differ considerably from those derived from the Commission's National Survey. The 1972 composite mean incidence figure for college student use of marihuana, for example, was calculated to be 50%; the corresponding 1972 National Survey figure, however, is 67%.

The seeming discrepancy is not in the figures themselves but in what they represent. It should be remembered that the National Survey figures were drawn at one point in time from a national household probability sample, and the figure presented is the actual figure reported by the respondents. The student survey figures, however, are composites; they represent the average (not actual) figures reported from selected local on-campus surveys whose composite may not be representative of all secondary school and college students in the United States.

They do, however, indicate demographic characteristics of particular student bodies whose experience with drugs may have increased relative to that of the population as a whole. From the National Survey figures, for example, we know that drug experience generally tends to be greater among teenagers and young adults than among pre-teens and those over 30; among those residing in metropolitan rather than in rural areas; among those in the Northeast and West than in the South and North Central areas. These same tendencies appear in the data drawn from the student surveys.

The figures presented here are meant to be taken as indicators, not as absolutes; they are intended to provide some guidance relative to the nature and extent of drug experience among a substantial though not necessarily representative sample of the student population.

To the extent that the students surveyed begin to mirror the student population-at-large, figures and trends similar to those found in the National Survey will emerge. The extent to which they are different, however, signifies the existence of some sampling bias.

The Commission places confidence in both figures, however, and the reader is cautioned to utilize the data in the context presented rather than to compare them absolutely one to the other. They demonstrate conclusively that the incidence of drug use among secondary school and college students has increased dramatically, both absolutely and relatively, since the late 1960's.

° The degree to which the survey, if repeated several times and the results combined, would yield similar estimates.

7 The degree to which the estimates drawn from the sample mirror the "true" figures of the total population, if one were to query everyone.

The figures cited below relative to the incidence, prevalence and patterns of student drug use have been extrapolated or calculated from data presented in approximately 200 surveys of American secondary school and college students conducted in all parts of the country from 1967 to 1972. (See Bibliography, Chapter Two, pp. 413-433.) This kind of aggregate analysis completed last year relative to experience and experimental correlates of marihuana use, which proved instructive in making sense out of seemingly divergent and disparate findings, will be repeated this year relative to discussions on the incidence, prevalence and patterns of drug use.8 The drugs included in this analysis have been classified as follows: alcohol, marihuana, inhalants (glue and other vapors or volatile intoxicants), "hallucinogens" (LSD, mescaline, STP and similar drugs), "stimulants" (amphetamines, methamphetamines, pep pills, cocaine), "depressants" (the range of sedative anti-anxiety agents ranging from barbiturates to "minor tranquilizers") and opiates (heroin and other opium derivatives).

COMPARATIVE NATIONAL SURVEY STUDENT DATA

Before examining the student survey data it is instructive to provide a backdrop against which they can be viewed. Information about secondary school and college student drug-using behavior gathered in the Commission's National Survey provides a basis for comparison.

The National Survey data show that 73% of the junior high school students, 87% of the senior high school students and 98% of the college students have consumed some type of alcoholic beverage at one time or another. When asked more specifically about their drinking behavior during the week prior to the survey, student respondents universally indicated relatively low levels of consumption. The majorities of all three student groups reported drinking five or fewer glasses of beer and wine or one or two drinks of liquor or less during that time period.

Beer was the most popular drink in all three groups. Among the junior high school students, beer (10%) and wine (9%) were consumed about three times as often as hard liquor (3%) ; more than twice as many high school students reported drinking beer (23%) than either wine (10%) or liquor (10%) ; and among the college students, beer consumption (66%) occurred more than twice as often as wine (31%) and about three times as often as liquor (24%) within the week prior to the survey.

As the Commission stated last year in its aggregate analysis of marihuana use surveys :

[L]arge differences in the populations addressed, the survey and sampling methods utilized and the terminology and operational definitions employed have precluded precise comparison of their results. Perhaps surprisingly, however, while any one survey is likely to provide a point estimation of ever or current use of [drugs] two or five or ten times greater than that found in another survey of a roughly similar population . . ., more careful sorting and analysis of [many] such surveys indicate the existence of patterns and regularities along several dimensions (NCMDA, Appendix, 1972: Vol. I, 250).

Comparison of the three student groups on their recent drinking behavior reveals that college students were more than six times as likely as junior high school students, and about three times more likely than senior high school students to have consumed beer; but were eight times more likely than the junior high and a little more than twice as likely as the senior high students to have drunk hard liquor. Wine consumption during the previous week was reported three time more often by college students than by either junior or senior high school students.

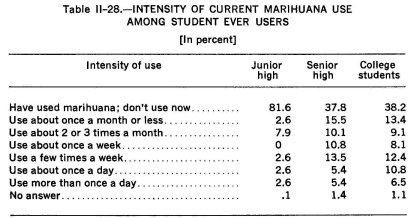

Some experience with marihuana was reported by 8% of the junior high school students, about one-fourth (24%) of the senior high school students and two-thirds (67%) of the college students. Eighty-two percent of the former group and 38% of the two latter groups of students who had such experience, however, reported that they no longer used the drug. Of those who were still using marihuana at the time of the National Survey, the majority reported low to moderate levels of use. Less than two percent of all students surveyed could be characterized as heavy marihuana users ( See Table 11-28) .

Five percent of the junior high school students, 8% of the senior high school students and 2% of the college students reported experience with glue or similar inhalants. All of the college sniffers, 63% of the high school sniffers and 44% of the junior high students with glue experience, however, indicated that their most recent use was more than a year ago. None of the junior high school sniffers but 7% of the senior high school sniffers reported using glue or a similar inhalant within the week prior to the survey.

College students were three times as likely as high school students (27% v. 9%), and high school students three times as likely as junior high school students (9% v. 3%) to have tried LSD or similar hallucinogens at least once. About three-fourths of the college triers, however, reported their most recent use as more than six months ago (40% indicated their last use was more than a year ago). High school students tended to have used hallucinogens more recently. About one-fifth of those with LSD experience said they last used this or a similar drug more than six months ago (for 12% it was more than a year ago) ; 41% indicated their most recent use as between one and six months ago ; and 35% used it within the past month (14% within the past week). Among the junior high school LSD ever users, 13% reported use within the past month (half of them within the past week) ; one-fifth (20%) reported last use between one and six months ago; and 46% stated that their most recent use of hallucinogens was more than six months ago. One-third of all junior high students with LSD experience reported their last use as occurring more than one year ago.

The Commission's National Survey data show that heroin was the drug least likely to have been used by both secondary school and college students. Only one of the junior high school students (0.2% of that group), seven high school students (1.1%) and 12 college students (4.3%) reported having tried heroin at least once. All of the college student ever users indicated that their last use of heroin occurred more than a year ago. Four of the high school student ever users reported their most recent use of heroin was more than six months ago, two of those noting it was more than a year ago. The remaining high school ever users reported most recent use between one and six months ago; none had used heroin within the week prior to the survey.

Despite the fact that cocaine is generally less available and more expensive than heroin, student experience with cocaine is greater than that reported with heroin; 1.2% of the junior high, 2.6% of the senior high and 10.4% of the college students reported experience with cocaine.

Between one-fourth and one-half of all students who have tried this drug report their most recent experience occurred more than six months ago (junior high school : 50%; senior high school : 25%; college: 31%), while approximately one-third of all three student groups (33%, 38% and 31%, respectively) reported using cocaine within the month.

College students were three times more likely than high school students and about eight times more likely than junior high school students to have tried ethical stimulants or depressants. Roughly 4% of the youngest group, 10% of the high school students and 33% of the college population had used these drugs at some time in their lives. It should be noted, however, that these figures include use for both medical and nonmedical reasons.

In an effort to provide a gross estimate of the frequency with which these pharmaceuticals are consumed, junior and senior high school students were asked to indicate whether their use of these substances was confined to one or two instances or whether it tended to occur more often. More than half of the high school students (54.5%) but only 14% of the junior high school stimulant ever users reported that they had used these drugs only once or twice. The corresponding figures for ethical sedatives and tranquilizers were 31.5% and 29.4%,. respectively. Thus, more secondary school students had used ethical depressants more frequently than they used ethical stimulants.

Among the college students, slightly more than one-fifth (22%) of those who reported experience with ethical stimulants indicated that they no longer used these drugs, and an additional one-third (32.6%) of these ever users said they had taken ethical stimulants only once or a few times. Only three of these students (3.3% of the ever users) indicated that they used these drugs whenever they wanted to (a reported frequency of more than once a week) .

Keeping these figures in mind, we now turn to the data gathered from the numerous student surveys collected by the Commission.

INCIDENCE OF STUDENT DRUG USE

Alcohol

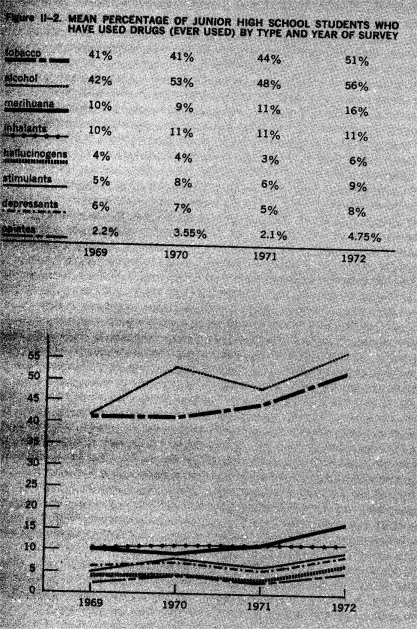

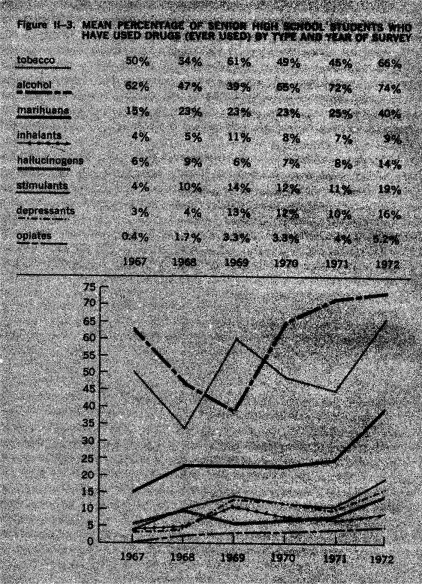

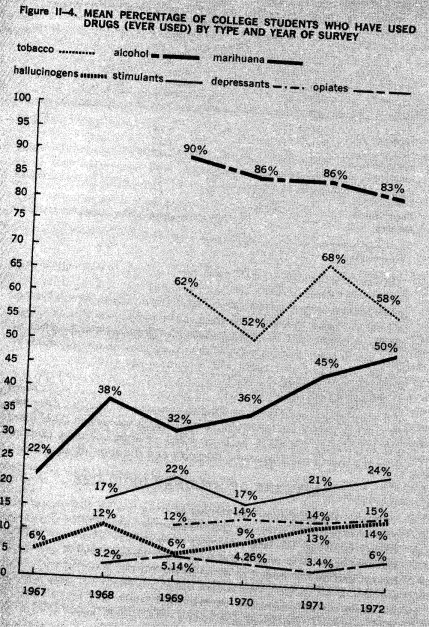

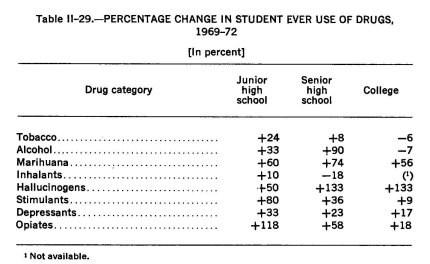

Among junior high school, senior high school and college students, alcohol is, by far, the drug of choice. Figures extrapolated from student surveys show that by 1972, approximately 56% of the junior high school students, almost three-fourths (74%) of the senior high school students and 83% of the college students have used alcohol at least once. (See Figures 11-2, 3 and 4)

The trends (percentage change) in ever use of alcohol among the three student groups between 1969 and 1972 are shown in Table 11-29. The data reveal a small percentage decrease (-7%) in ever use of alcohol among college students but significant percentage increases for the secondary school students, Particularly those in the senior high school grades ( + 33% and +90%, respectively) .

Examination of the figures on the growth rate of alcohol use relative to the incidence of other drug use for the period 1969 to 1972, reveals three separate and distinct patterns. (See Table II-29) Among junior high school students, although alcohol maintained its substantial lead over all other drug types in the incidence of use, the gap was beginning to close. Over the four year period, the percentage increase in the incidence of use of all drugs, except tobacco and inhalants, was equal to or greater, in several cases, much greater, than the percent increase in the incidence of alcohol use.

Among senior high students, a very different picture emerged. The large increase in the incidence of alcohol use ( +90%) over the four year period was surpassed only by the larger percent increase in hallucinogen use ( +133%), but was trailed fairly closely by the increase in marihuana use ( +74%). All other drug types show percentage increases far below that of alcohol, and the incidence of tobacco use actually decreased.

For the college students, yet a third pattern emerged. Relative to the incidence of alcohol, which Showed a percentage decrease, use of all drug types except tobacco and inhalants increased. The incidence of hallucinogen use showed the highest rate of growth ( +133%), followed by marihuana ( +56%) and still farther behind were the opiates, depressants and stimulants, in that order.

In sum, although the incidence of drug use has generally increased among secondary school students, percentage increases in the number of students who have tried marihuana, hallucinogens, stimulants, depressants and the opiates have begun to approach, equal or surpass the percentage increase in the incidence of alcohol use among students at the secondary school level. At the college level, the proportion of students who reported ever use of alcohol in 1972 declined somewhat while ever users of other drug types, particularly the hallucinogens and marihuana, continue to increase.

Marihuana

Data from the student surveys show that next to alcohol, marihuana is the most popular intoxicant among both secondary school and college students. By 1972, approximately 16% of the junior high school students, 40% of the senior high school students and 50% of the college students in the United States reported using marihuana at least once. (See Figures 11-2, 3 and 4)

Between 1969 and 1972, the percentage of junior high school, senior high school and college students reporting ever use of marihuana increased by 60%, 74% and 56%, respectively. (See Table 11-29) For the secondary school populations, the largest percentage increases occurred between 1971 and 1972 (junior high : 46%; senior high : 74%). ,At the college level, however, the largest percentage increase occurred one year earlier, between 1970 and 1971.

The fact that the 1971-72 percentage increase for ever use of marihuana among college students (11%) dropped below the corresponding figure for 1969-70 (13%) suggests that at least for college students, the magnitude of yearly increases in the percentage of students who have tried this drug has begun to decline. This finding suggests that the incidence of marihuana use in this population may have reached its peak and may be levelling off, as was suggested by this Commission in its 1972 Report and is indicated in the findings of two Commission-sponsored national surveys.

Further, because many more students in junior and senior high school have tried marihuana before they go on to college, we may expect to reach a saturation point on the incidence (ever use) of marihuana among the college populations in the not too distant future. This hypothesis finds additional support in the survey data on patterns of use and projected future use of marihuana. These data, to be discussed in detail later on, show that most of the students who have not yet tried marihuana do not plan to do so in the future; and that most of the ever users experimented with the drug only a few times, terminated its use, and did not plan to use it again. If this is the case, we should not expect that those who tried marihuana and terminated its use in junior high school will repeat the process in either senior high school or college. Consequently, one might suggest that the point in time at which the percentage increase in the incidence of marihuana use reaches its peak at the junior high school level will signal the beginning of a decline in total use of marihuana among future generations of secondary school and college students.

This is not to suggest that marihuana use will be totally eliminated or terminated, as there will probably always be a certain number of ever users who continue to use marihuana with varying degrees of frequency and intensity. It does suggest, however, that the proportion of students who may be expected to experiment with and to continue use of marihuana will stabilize and possibly decline within the foreseeable future.

Inhalants

The survey findings suggest that experimentation with inhalants occurs primarily among junior high school students, begins to wane among senior high school upperclassmen and disappears almost entirely once a student enters college. Surveys undertaken during 1972 show that 11% of the junior high school students, 9% of the senior high school students and only about 2% of the college students 9 have tried inhaling volatile solvents at least once. (See Figures 11-2 and 3)

The data also show that the percentage of secondary school students who try inhalants has remained relatively stable since 1969, when the popularity of the practice seemed to have reached its peak, and that use of these volatile substances, once initiated, is quickly extinguished ; on the average, two-thirds of the junior high school students and 70% of the senior high school students terminated this practice after experimenting with these substances once or twice.

° The number of surveys presenting data on college ever use of inhalants was too small to present graphically, but the reported figure is based on eight separate estimates between 1969 and 1972.

Hallucinogens

In direct contrast to the inhalants, experimentation with hallucinogens is generally limited to high school upper classmen and college students. Also dissimilar to the inhalants is the trend line of hallucinogen use ; although the practice of sniffing glue and other volatile solvents began to wane after 1969, experimentation with LSD and other hallucinogens did not increase significantly until after that time.

The greatest percentage increases in the incidence of hallucinogen use among secondary school students were not experienced until about 1971; for college students, however, the significant yearly increases began about 1969. (See Figures II-2, 3 and 4) For the four year period, 1969-1972, the numbers of junior high school, senior high school and college students reporting use of hallucinogens at least once increased by 50%, 133% and 133%, respectively. (See Table 11-29)

Despite these large increases in the ever use of hallucinogens, the number of students who reported in 1972 that they had tried these drugs remained far below the ever users of marihuana among all three student populations, and considerably below inhalant ever users among junior high school students. Hallucinogen ever users also trailed, although by a much smaller margin, ever users of stimulants among senior high and college students and ever users of depressants in senior high school. In 1972, 6% of the junior high school students and 14% of the senior high school and college students reported having tried hallucinogens at least once. (See Figures 11-2, 3 and 4) If this current trend continues, we can expect these figures to climb higher over the next several years.

Stimulants

As of 1972, 9% of the junior high school students, about one-fifth (19%) of the senior high school students and approximately one-fourth (24%) of the college students had taken stimulants at least once. (See Figures 11-2, 3 and 4) Similar to the trend for hallucinogen ever use, the proportion of college students who tried these drugs began to increase significantly in 1970 and continued upward in 1972 (an increase of 41% over these two years). The significant percentage increase among secondary school students followed by about one year the percentage increase for college students, but the magnitude of this one-year increase for both groups of secondary school students exceeded the two-year increase noted above for the college population (50% for the junior high school students and 73% for the senior high school students).

Depressants

Among junior high school students, the specific incidence figures and the trend line for ever use of depressants closely parallel those noted above for the stimulants; the proportion of students reporting ever use of depressants rose from 6% in 1969 to 8% in 1972, a four-year increase of 33%.

Among the senior high school students, the magnitude of the four-year percentage increase was somewhat smaller (23%), but by 1972, 16% claimed to have taken depressants at least once, a 60% increase over the preceding year.

Among college students, the four-year percent increase to 1972 was smaller (17%) than that of either group of secondary school students, but by 1972 a sizeable 14% of the college student population reported having used depressants on at least one occasion. Unlike the pattern for stimulant use among these students, however, the percentage of ever users has remained stable since 1970 when the ever use figure jumped two percentage points over the corresponding 1968 and 1969 figures.

These data suggest that although experimentation with depressants among college students may have levelled off, the relatively high incidence of ever use is likely to be surpassed by future generations of college students. The level of ever use of depressants among senior high school students is already approaching the college level, and junior high school students are well on their way to catching up.

Opiates

In contrast to survey findings drawn from samples of inner city populations, school drop-outs or minority groups, the incidence (ever use) of heroin and other opiate use among secondary school and college students as a whole is comparatively low, increasing from about 2% to 6% between 1969 and 1972. (See Figures 11-2, 3 and 4)

This is not to suggest, however, that these figures are insignificant or that the phenomenon of opiate use among students is stabilizing or diminishing. Rather, all three student populations have experienced significant increases in the proportions of those who have at least experimented with one or more of the opiates (junior high school : 118%; senior high school : 58%; and college : 18%). (See Table 11-29) Contrary to prevalent public opinion, however, the largest majority of these opiate ever users terminate use of these drugs after experimenting with them one or a few times. Only a small proportion of the ever users in the student population go on to become frequent users or reach dependent status.

In sum, the incidence data drawn from secondary and college student surveys demonstrate a substantial, significant and rapid increase in the number of young people who have tried various types of drugs at least once and thereby enter the pool or population at risk. These figures, however, tell us nothing about the prevalence or patterns of drug use in these student populations; they provide no indication of the proportion of ever users who terminate use after one or a few experimental trials or the relative proportion of either the total student body or the ever users who go beyond their initial experiences and adopt patterns of more prolonged, frequent or intensive drug use. In order to determine the extent to which such conversion takes place and to identify the usage patterns which emerge, one must examine data relative to the frequency, intensity and duration of drug use.

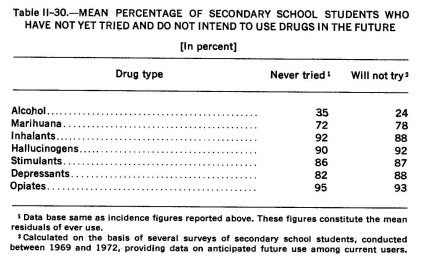

PATTERNS OF STUDENT DRUG USE

Despite the heightened awareness of drug use by their peers, the greater exposure to drug use and the increased availability and accessibility of drugs, the large majority of secondary school and college students have never used drugs other than tobacco, alcohol and marihuana, and do not intend to do so in the future. Many of those who try any or all of the psychoactive drugs terminate use after satisfying their curiosity in a few experimental trials; and many of those who continue to use drugs, even over a considerable period of time, do not escalate from occasional or intermittent social and recreational use to more frequent and intensive, personally motivated patterns of use.

Perhaps the most instructive finding to emerge from these survey data is the consistent reappearance of these patterns, regardless of the location of the survey, the type of student body queried, or the age or point in time of the reported initiation of drug use. These data indicate that despite the significant overall increase in the incidence of drug use and the large differences in the magnitudes of these increases according to drug type, the patterns of drug use which have emerged among this vastly enlarged pool of ever users have remained relatively unchanged over this period. Although the population at risk has increased, the relative proportions of frequent and regular drug users drawn from this pool have remained fairly constant. A closer examination of some of these data should serve to illustrate this point.

Present and Future Drug Involvement

Figures from the latest student surveys show that as of 1972, between 82% and 95% of the secondary school students, for example, have never tried opiates (95%), inhalants (92%), hallucinogens (90%), stimulants (86%) or depressants (82%) and that approximately equal percentages (78 to 93%) of these students do not intend to use these substances in the future. (See Table 11-30) The corresponding their curiosity in a few experimental trials; and many of those different.

Although the never users of marihuana constitute a much smaller percentage of the secondary school and college student populations (72% and 50%, approximately), about three-fourths of these students (78% and 74%, respectively), like the other non-users, report that they do not expect to use marihuana in the future.

The incidence and future use of tobacco and alcohol provide the only dramatic exceptions to this trend. As already indicated, the use of alcohol at least once has been reported, on the average, by approximately 65% of secondary school students (56% of the junior high and 74% of the senior high school students in 1972). In contrast to all other non-drug users, however, only about one-fourth of the current never users of alcohol think they will remain non-users in the future.

Among the college students, only about 17% report they have never tried an alcoholic beverage. Only one college survey asked specifically about future use of alcohol, suggesting that its use is, prehaps, expected in future generations of college students. In this one survey, conducted in 1970 in the Midwest, only 2% of the ever users (the nonusers were not queried) said they would not use alcohol in the future, 4% were undecided and 93% of the ever users said they planned to continue use of alcohol (Williamsen, 1970)."

Of more immediate social concern than the present never users for whom prevention mechanisms might reinforce their present intentions, is that rapidly expanding group of student ever users referred to earlier. Can and should we expect their drug use to continue into the future and to escalate in frequency and intensity ? Or is it likely that many of these students will, on their own initiative, discontinue their experimentation and terminate drug use once their curiosity is satisfied, and the initial excitement and mystique have worn off ? To provide at least tentative answers to some of these questions and inferences about others, we again turn to the student survey data.

In sharp contrast to the never users, whose future drug use appears generally unlikely (except for use of alcohol), the future plans of those who have tried various drugs at least once are more uncertain, somewhat more variable and less predictable. The data indicate that substantial proportions of ever users will probably terminate use, and that those who continue will tend to stabilize their drug-using patterns. Both of these findings vary according to the type of drug used and the frequency, intensity and duration of current use.

" Figures do not total 100% because of rounding.

Despite substantial differences between drug types in the percentages of the ever users who plan to continue use in the future, secondary school students did not differ significantly from college students regarding future use; somewhat more of the former (about one-fourth) than the latter (slightly under one-fifth) were undecided on the issue. The ever users of alcohol among both student groups were again most likely to report definite or likely future use (between 70 and 93% said yes) . More than half of the ever users of marihuana also indicated they would use the drug in the future. Following far down the line, slightly more than one-third of the pill users (stimulants and depressants), 30% of these who had tried hallucinogens, about one-fourth of those who had used opiates at least once and about 14% of the glue sniffers expected to try these drugs again.

It was evident that most of the students had already made a decision either to continue using the drug or to discontinue it. When secondary school students, for example, were asked if they were still using a given drug type at the time of the survey, on the average about 55% of the ever users of marihuana, 16% of the ever users of inhalants, 40% of the ever users of hallucinogens, one-third of the ever users of stimulants or depresssants, and about one-fourth of the ever users of opiates responded affirmatively, figures which closely correspond to responses to questions regarding future use of these substances.

Frequency and Intensity of Drug Use

Up to this point, the data presented on student drug use have indicated that with the exception of alcohol, the majority of past and current non-users can be expected to remain non-drug users in the future ; and a variable but substantial proportion (45% to 85%, on the average) of ever users have already terminated drug use and can also be expected to refrain from future drug use.

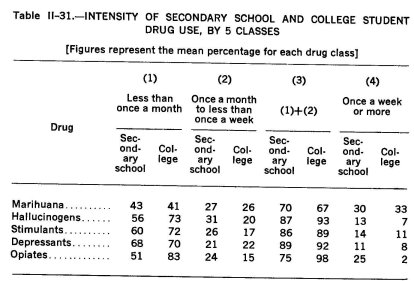

What, then, can be said about the nature and extent of drug use among those students who currently use drugs and plan to continue use ? And what inferences may be drawn and what should be expected regarding the usage patterns of the next generation of drug users? As to the first question, with the exception of alcohol, the majority of student drug users generally adopt and maintain patterns of low frequency (total use of ten times or less) and low to moderate intensity (less than once a week) regardless of the duration of use (that is, the length of time they continue to use drugs). Furthermore, these relatively low-use patterns have not changed appreciably since about 1967, the earliest year for which sufficient data were available.

These findings, however, should be qualified by reference to several problems encountered in analyzing the available data. As noted in the Commission's Appendix to its Report on marihuana, large and irreconcilable differences in terminology and operational definitions which are commonly employed to describe patterns of drug use invariably exist in the surveys examined. Failure to distinguish amongfrequency, intensity, amount and duration of use 11 was particularly troublesome in the surveys dealing with more than one drug. Consequently, some structure had to be provided in the interpretation of these data in •those instances where confusion or an absence of clear definition was manifiest. The Commission is fairly confident that its occasional but necessary categorization of some unspecified informational items resulted in no significant distortion of the findings regarding drug usage patterns.

Turning now to the data, the surveys reveal that with the exception of alcohol in the case of college students, between 60 and 85% of the ever users among both secondary school and college students report their lifetime usage for each of the classes of drugs to total no more than ten times. Comparisons, by drug class, of these low frequency secondary school and college users reveal no significant differences relative to marihuana use (60% and 59%, respectively). Almost twice the proportion of secondary school students, however, reported low frequency use of alcohol (62% vs. 32%) ; and in the case of the hallucinogens, stimulants, depressants and opiates, proportionately more of the college students turned up in this low frequency category. This was especially true of opiate use; 71% of the secondary school ever users and 83% of the college students ever users reported their total use of opiates as ten times or less.

These data raise several questions, especially when viewed against the comparative incidence data presented earlier. First, why is it that these relatively dangerous drugs are used with somewhat lesser frequency by the college student who is generally believed to be more heavily involved with drugs? And how does one explain the comparatively high frequency of use among the younger, theoretically less drug-involved secondary school student? Several possible explanations can be advanced, most of which relate to the motivation for use.

11 In large measure, this dilemma stems from the necessity of trying either to isolate or combine four separate and distinct issues : (a) the frequency of use, that is, the total number of times an individual has used (any given) drug ; (b) the intensity of use, that is, often one uses (a drug) within any given time period ; (c) the amount of use, that is, how much (of a given drug) was used ... either totally, within a given time period or at any one sitting ; and (d) the duration of use, that is, how long one has used the drug (the number of days, weeks, months or years) between trial number one and either the present or the time use was terminated (NCMDA, Appendix, 1972: Vol. I, 312).

The available data suggest that peer influence toward drug use may be greater for junior and senior high school students than for college students. This situation, coupled with the novelty of drug use in the younger group and the relative immaturity of the younger students, may provide at least part of the explanation. Conversely, the greater maturity of the college students, their increased exposure to drug use among their peers, and their greater opportunity to observe the effects of these substances on their friends and colleagues may serve to alter their own behavior and to encourage greater discrimination in their drug-using behavior.

Most important are the divergent motivations for drug use and the varying perceptions of the relationship between the act of use and the desired or expected outcome. At the secondary school level, most drug experimentation is motivated out of curiosity; a desire to experience something new ; a need to test the effects which young people have learned to expect or anticipate ; and a psychological drive to win peer approval or recognition by participating in a shared group experience. The primary focus, then, is on the act of drug taking and its attendant rituals and social activity.

At the college level, however, the focus appears to shift from the act of drug taking to the outcome of that behavior. Greater exposure to a particular drug and increased opportunities to observe and experience the drug's effects may serve to satisfy the initial curiosity, excitement or thrill of a new experience and to minimize the undifferentiated behavior generally characteristic of new experiences. These older users apparently enjoy the effects of the drug and associate some pleasure with both the experience and the outcome. Their greater social maturity and ability to maintain control over their behavior is reflected not only in their apparent self-limitation of the circumstances and conditions under which they permit drug use to occur (as is evident from the intensity data to be discussed below) but in their apparent desire to regulate and moderate the frequency and intensity of that activity.

The corresponding intensity data provide additional support for this hypothesis. Again, with the apparent exception of alcohol and marihuana, the majority of these students report use at a rate of once a month or less. No significant difference was found in the proportion of secondary school and college students who used either marihuana (approximately 43% and 41%, respectively) or the depressants (68% and 70%, respectively) at this low level of intensity. However, college users were more likely than secondary school users to use hallucinogens, stimulants and opiates less than once a month. The greatest difference (51% vs. 83%) appeared with respect to the opiates.

Up to this point, we have devoted attention exclusively to the low frequency, low intensity users. Before proceeding to discuss the more frequent and more intense patterns, however, we should at least note in passing that even the vast majority of these heavier users appear in what might, for the moment, be termed the intermittent to moderate frequency and intensity categories (use a total of 10 to 50 times or continued use at a rate of once a month or more but less than once a week). For the five drug classes about which there is adequate and Sufficient information on both student user groups, the data demonstrate that the vast majority of all student users limit their drug use to a level generally well below once a week. The intensity data in Table 11-31 illustrate this point.

Further, although a small increase has occurred in the proportion of student ever users who escalate to moderate or more intense use of drugs, the intensity distributions presented in Table 11-28 have remained fairly constant over the seven-year period (1967 to 1972) for which survey data are available. In sum, despite the increasing incidence of drug use, there is no indication that higher proportions of these ever users will escalate to higher frequency and intensities of drug use. Rather, if the past and present trend continues, we should expect that substantial proportions of those who have tried these drugs will terminate use after relatively short-lived drug-using careers and that the vast majority of those who continue to use them will do so with relatively low frequency and intensity, especially as they mature and become increasingly informed about drug effects.

The Commission places heavy emphasis on the maintenance of regular and heavy drug usage patterns for several reasons. First, the data indicate that even at this level, considerable attrition takes place as the students move on from high school to college. Secondly, the data also show that even among those who use drugs at least once a week, substantial differences exist in the exercise of individual control over the frequency and intensity of use, in the presence of psychopathology, and in the degree of social acceptability and public tolerance accorded drug-using patterns and consequences.

The data in Table II-31, for example, show on the average twice as many high intensity users of hallucinogens and 12 times as many high intensity opiate users among secondary school students than among college student users. The differences are smaller but still follow the same pattern for stimulant and depressant use. In the case of high level use of marihuana, no difference was found between the two student groups.

The survey data demonstrate overall that those who use drugs once a week or more range from 2% to 33% of all ever users, depending upon the drug and the age-grade status of the student. Most important, however, the majority of these high level users (one-half to over three-fourths) fall closer to the "once a week" than to the "at least once a day" end of the continuum. As such, most of these high intensity users represent the weekend party marihuana, hallucinogen or speed user who generally confines his use to these weekly social occasions. Not surprisingly, the individual physiologically or psychologically dependent upon these substances appears rarely in these student populations.

Duration of Student Drug Use

Earlier in this chapter we indicated that the greatest incidence of drug use (ever use) occurs among the college students and decreases progressively down to young people in junior high school. Examination of the prevalence data suggests the converse; comparatively more college students than junior high school students have terminated or significantly reduced drug use, though the attrition rate was found to be substantial at all levels.

Data on age of onset give us further insight into the overall duration of student drug use. On the average, about 60% of the college students who have tried drugs report beginning use while in college ; between 4% and 10% say they started in junior high school; and about one-third report onset at some time in senior high school.