| - |

Drug Abuse

V PREVENTION

The Commission notes that "drug abuse" prevention is a function long professed by all levels of government but rarely planned by any of them. Until the last decade, this notion was identified exclusively with the law : primary prevention was to be achieved by the law's deterrent force ; when that failed, secondary prevention was to be achieved by coercive intervention in the life of the user. With the onset of contemporary pessimism about the utility of law, prevention has become synonymous with any education or information program which refers to the dangers of drug use.

All efforts which now go under the heading of prevention are characterized by a fundamental ambiguity : What is society trying to prevent ? In analyzing the proclaimed objectives of preventing dysfunctional drug use, irrational decisions due to lack of information regarding drug use, drug dependence, irresponsible behavior, inadequate coping, or (most commonly) "drug abuse," it is obvious that the implicit objective of almost all existing prevention programs is to stop all use of currently illegal drugs.

With the apparent failure of this approach, a. rising clamor has been heard to turn prevention efforts toward the underlying causes of drug use. These causes are commonly linked to the same conditions whose correction will presumably resolve most of our major contemporary social problems. This solution, however, will require a major alteration of our social system, taking years to achieve. A prevention strategy based on remedying basic social ills therefore does not provide a serviceable guide for an effective response in the immediate future.

Related to these questions of objectives are the dual assumptions about drug-using behavior upon which the preventive effort appears to be based. First, the hope persists that if we could only give people the facts about drugs, they would act in their best interests. It is generally assumed that presentation of information regarding the dangers and risks of drug use will dissuade people from indulging. Second, the popular "contagion" theory of drug use suggests that ideas which encourage drug use must be suppressed.

The preventive effort can be thus summarized : purify the population by removing those persons and messages citing the "benefits" of drug use, and then educate the uninfected population with information detailing the risks of this behavior.

This set of assumptions contains serious logical flaws. The data presented in Chapter Two show that large percentages of the population, particularly the youth who are the primary target of prevention programs, would have to be quarantined to prevent the spread of ideas about the perceived advantages of drug use. More important however, attitudes about the utility of drugs stem from socially acceptable be-346

havior as well as that which is disapproved. It is impossible to hide the fact that people perceive advantages in the use of drugs.

The other support in the prevention ideology is equally shaky ; presentation of information regarding the dangers and risks inherent in drug use is unlikely to achieve the hoped-for result. It is difficult at best to educate people not to do something on moral grounds, as opposed to showing them haw to do something.

The entire area of drug use prevention as presently conceived is, unfortunately, mostly wishful thinking. In this section, the Commission will survey the existing approach and offer our own view regarding the appropriate response.

THE INFORMATION—EDUCATION EXPLOSION

Over the last five years, an enormous amount of information on the drug phenomenon has been transmitted to the public. The assumption has been that information-education-training 67 programs, dispensing information about substances and available treatment services, will cause people not to take drugs, or stop if they already do so. The high visibility of the drug problem has led to significant investment in this, as in other types of possible solutions.

At the present time, no one can even accurately assess the scope of the information-education effort, much less measure its impact on behavior. There is no federal information exchange to which independent programs report; no description of all programs currently in operation; no assurance that the information disseminated is correct; no check to see that it is reaching its intended audience. We can, however, get some idea of the magnitude of this information explosion by sketching the response of the governmental and private sectors.

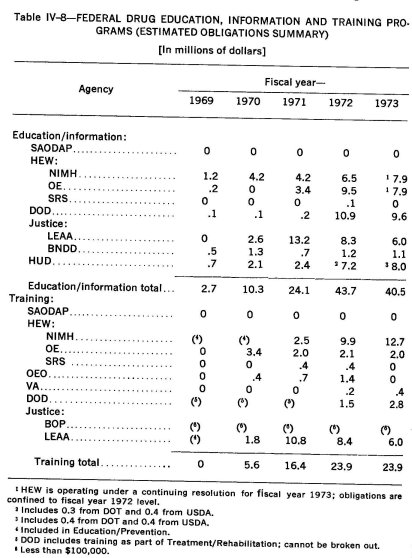

Federal outlays for education, information and training increased from $15.9 million in fiscal year 1970 to an estimated $67.6 million in fiscal 1972. This sizeable federal effort is administered by 10 separate federal agencies. (See Table IV-8) Of these federal funds, about 60% are spent directly on information production and dissemination, while the remainder goes to training programs.

Each state department of education receives federal funds to develop a drug education syllabus and curriculum guide and to provide state level consultation to teachers and administrators. The Office of Education allocated $2.6 million to state education agencies in Fiscal Year 1972 but did not require outcome accountability of such efforts or provide a summary of all funded programs. Regulations issued under Title I of the Higher Education Act of 1965 establish program guidelines for federally-funded drug information-education programs, but a shortage of staff has forced the federal office to rely on exhortation rather than inspection to obtain compliance.

State departments of mental health, by whatever title designated, have also started many drug education programs. While NIMH has provided partial support for some of these efforts, funding is on a project-by-project basis rather than at the state level, as is the case with the Office of Education-supported programs Overview of these efforts would require locating the responsible officials at each level of state government and sifting through individual descriptions of programs.

There are over 17,000 school districts in the United States. Many of them are conducting drug education programs, and the problems of monitoring their efforts are correspondingly greater than that of monitoring state programs.58

Government-sponsored programs account for only a portion of the current investment in drug education. There are numerous large foundations and organizations of national scope which either sponsor their own programs or influence those developed by others. For example, the Advertising Council estimated on the basis of its members' reports of value of time and space donated for drug information dissemination that the private sector investment approached $37 million in calendar year 1971. Numerous professional, trade and industry groups have sponsored drug education efforts of various kinds, with different target groups in mind, and using different approaches. Programs are conducted by churches, civic groups, businesses, national voluntary organizations, and the military services, to name just a few.

In addition to the many current educational efforts, there are numerous media productions of mixed educational-entertainment purposes such as magazine and television specials, drug-related episodes in various television weeklies, and feature length films with drug themes. Though intended as entertainment, many of these presentations have had an impact on attitudes toward drug use. The news media, too, have given prominence to drug-related events and developments. Exactly how these presentations interact with information from education program is, of course, unknown.

Until the types of information disseminated by all sources are ascertained, a comprehensive evaluation of their cumulative effect on behavior is impossible. The usual non-controlled field study can never isolate any one program or project for impact assessment. There exists, however, one "real life experiment" which assesses the relative effectiveness of various media in the field; this survey has polled 100 households to measure pre-existing attitudes and to evaluate the ultimate influence of a community-wide mass media campaign. Results thus far indicate that four out of five adults and two out of three children recalled seeing drug messages on television ; 60% of the adults and 49% of the children remembered printed drug information ; 29% of adults and 35% of the children recalled radio messages. The fourth most remembered medium of communication was the school lecture, attended only by the school-age children (John F. Kraft, Inc., 1972).

Despite a substantial investment in information-education programs by public and private sectors alike, the federal government is only now beginning to think about evaluation and strategy. The National Institute of Mental Health and other divisions of the Department of Health, Education and Welfare have recently launched several studies. Further contracts will be designed by SAODAP, which by statute has assumed responsibility for evaluation in the drug education area. It appears likely that SAODAP will initiate impact assessment studies, including essential cross-program comparisons and cost-benefit analyses.

Even without comprehensive evaluations, at least two clear conclusions emerge from isolated studies of different researchers: (1) most information materials now in the field are scientifically inaccurate and (2) most education programs operate in total disregard of basic communications theory.

For example, in 1972 the National Education Association Task Force on Drug Education said about the calibre of drug information flowing through the school systems :

... [M]uch false material has been produced for and used in drug education with widespread indiscretion in schools across the nation. Commercial agencies have taken advantage of the concern caused by the emergence of the drug problem and have produced and sold much material without thought of quality. The Task Force feels that use of false, poor, emotionally oriented, and judgmental materials is more harmful than no materials and is not indicative of the NEA's desire for high-level educational materials (National Education Association, 1972).

The National Coordinating Council on Drug Education has also pointed out the shoddiness of drug information materials in three successive volumes, containing expert ratings for accuracy and appeal of current drug education films. In the third edition, the Council found that 31% of the 220 films reviewed were so inaccurate, distorted or conceptually unsound as to be totally unnacceptable. Another 53% were classified as "restricted;" not suitable for general audiences and requiring special skill in presentation. Only 16% of the films were rated "scientifically and conceptually acceptable" (National Coordinating Council on Drug Education, 1972) .

Television spot announcements are no better. A recent two-week content analysis of televised drug appeals in the Hartford Metropolitan area indicates that 87% of the drug abuse messages contained only generalities, with no specific data or evidence. Moreover, producers of these spots seem to pay little attention to important questions of format, such as the kind of person used to communicate the information. Various target groups are likely to regard the same communicator with different degrees of credibility and respect (Hanneman, et al., 1972a) .

GOALS OF INFORMATION-EDUCATION PREVENTION

Much of the present effort to prevent drug use through information and education programs rests on the expectation that if everyone understood all the facts about prohibited drugs, very few would use them. The people and agencies designing the programs assume that the facts about illegal drugs, once they are fully known and considered, will point irrefutably toward abstinence.

Drug information and education, however, does not simply present the facts about drug use ; either consciously or unconsciously, the programs' sponsors also add their own value weights to the facts. Not surprisingly, in view of the objectives and the value systems of most drug educators, the risks of use receive heavy weighting, while the advantages which users perceive are treated lightly.

The problem with this approach is that it expects those who receive the information to weigh the costs and attractions in the same way as those who provide it. Drug information and education presentations often incorporate value weights into the facts themselves, and individuals who do not share the same perspective feel that some of the facts are exaggerated, while others are deliberately ignored.

This communications problem points to a basic dilemma in every program aimed specifically at use prevention. Prevention programs may proclaim goals which stress the prevention of high-risk drug use, or of drug dependence, or use of particular drugs, but in practice they must try to curtail all illicit drug use. Programs which expressly emphasize the harm in certain use patterns imply that other patterns are relatively harmless and thus tacitly condone them. Since this is unacceptable, education-information programs usually take the opposite tack; they suggest that all use patterns are equally harmful, because all are likely to evolve into undesirable behavior. From the program's point of view, such an argument may not seem an exaggeration. When the attractions of drug use are viewed as largely false, by comparison even a small risk becomes substantial. From the point of view of many recipients, however, the "all use is equally dangerous" approach undermines the credibility of the information.

The government's deep involvement in drug information dissemination adds another dimension to the dilemma. As long as government, especially the federal government, is the predominant force shaping this generation's response to drug use, it will be tempted to employ education and information programs not only to implement policy, but to rally support for it. If prevention programs must follow a carefully defined government line, their methods will be limited and their information suspect. The government may defend its policies to the public, but it is supposed to do this openly, not by disguising value choices as objective fact, or distributing propaganda under the cover of "education." On the other hand, government agencies will find it politically and practically difficult to fund and assist drug education or information programs which tend to contradict the premises underlying their own policies.

To design a rational strategy for drug information and education programs, both public agencies and private institutions have to resolve the basic dilemma. As we have noted, the present tendency is to treat the various value judgments as if they were objective facts about the risk of using drugs. The Commission recognizes the various pressures toward this approach, but believes that it is short-sighted. In time, confusing fact and opinion will discredit all information transmitted, and ultimately the source as well. Fortunately, drug educators themselves increasingly recognize this danger :

Information about drugs is so closely related to moral and social values, that the distinction between fact and opinion is often blurred. Thus, a number of writers emphasize that values should be explicitly distinguished from scientific observations and that a teacher should beware of selectively presenting only facts consonant with his own values (Brotman and Suffet, 1973) .

On a related issue, Helen Nowlis, Director of the Drug Education Section of the U.S. Office of Education has written :

It is probably wise to clearly separate the question of the dangers of abuse of individual drugs, both physical and psychological, from the question of legality. When a presentation of untoward effects of a drug, even the potential untoward effects, is designed to support the illegal status of the drug, battle lines are drawn on the basis of individual rights versus arbitrary authority and invasion of privacy, and none of the relevant issues is open to rational, unemotional consideration. (Nowlis, 1969)

Going to the other extreme, information and education programs might attempt complete objectivity in their presentations, either by trying to remove all traces of value judgment from the description of risk and attractions, or by giving opinions on both sides of the issue. Either way, the program itself would not inject values, but let the individual recipients apply their own.

While this is preferable to engrossing the facts with hidden value judgments, there are clearly disadvantages in such an approach, particularly where young people are concerned. The national experience with tobacco and alcohol use demonstrates that knowledge about risk in and of itself does not necessarily change behavior. Particularly when the attractions seem concrete, and the costs contingent and often remote, merely presenting unvarnished fact may do little good ; more seriously, it might do harm. Information and education programs which presented both sides of the issue of drug use could encourage more youthful interest and experimentation than they discouraged. Even a simple, objective statement of costs and attractions could arouse curiosity. In fact, any prevention program which focuses specifically on drugs and drug use will introduce the idea of consumption to the naive among its recipients.

A third possible resolution of the dilemma is to present both the facts and the weight which the predominant value system would give them, but to distinguish carefully between one and the other. Un-. doubtedly, this is not as easy as it sounds. For one thing, value judgments are not easy to transmit, particularly when they are identified as such. Second, the program would then have to deal with inconsistencies in the way society has applied its norms. Third, dealing with social values merely in terms of drug use can make them seem narrow, trite and somewhat arbitrary.

To illustrate these difficulties, we need only imagine the problems of an informational-education program dealing with marihuana use. In its candid and objective portrayal of marihuana's risks and attractions, the program would have to point out that many users have apparently found the euphoric effects pleasurable, while relative to other psychoactive substances the drug has a low risk potential and dependence liability. Next, it would have to show why values emphasizing self-control, personal fulfillment and improvement, and social responsibility disfavor use of any intoxicant, even a mild one. This task would be all the harder for having to explain why these same values tolerate the use of alcohol.

None of the three ways around the dilemma, then, are completely satisfactory, though the Commission feels that the last one is the most honest and complete. The real solution, however, would seem to lie in moving from a negative to a positive preventive approach. The Commission recommends that drug use prevention strategy, rather than concentrating resources and efforts in persuading or "educating" people not to use drugs, emphasize alternative means of obtaining what users seek from drugs: means that are better for the user and better for society. The aim of prevention policy should be to foster and instill the necessary skills for coping with the problems of living, particularly the life concerns of adolescents. Information about drugs and the disadvantages of their use should be incorporated into more general programs, stressing benefits with which drug consumption is largely inconsistent. Other programs should focus on improving the network of support for the individual at-risk, on providing goals and activities, or on encouraging a sense of purpose and self-esteem rather than on the presence or absence of a drug.

INFORMATION POLICY

In formulating information strategy, policy planners must first assess the practical impact of drug messages. Here, two important questions remain unanswered : can new communications technology be utilized to integrate available information into individual belief systems, and if so, how ?

Any information program seeking to affect behavior must first answer a number of basic questions which drug education and information projects have too long ignored. These issues might be summed up in a deceptively simple way by asking. "Who says What to Whom ?" ; that is, what person or institution is the apparent source of the information and what relationship does he, she or it have to the projected audience? Who is the audience, what are their current views on the subject matter of the program, how should these views change ? What kind of information is needed to effect the desired changes ? How should it be transmitted, by what media, by what persons, and in what form to ensure and enhance its reception by the intended audience ?

A planned information policy must take into account the complex relationship between a person's attitude toward an object or behavior, his perception about the consequences of the behavior, his evaluation of those consequences as good or bad, and his perception of the attitudes of those to whom he looks for approval. The information disseminated can be designed to alter or confirm his beliefs about the likely consequences of the behavior, either through accurate or inaccurate information. Or, though this is more difficult, it can be designed to alter or confirm his evaluation of the consequences, or to alter or confirm his perception of the attitudes of others.

Comprehensive information strategy can be planned only after research has determined attitudes, perceptions, and normative influences for target populations. In addition, the audience to whom the information is directed should be carefully selected. For example, available data indicate that a large portion of the youth population have used or presently use illicit drugs, making especially important programs and approaches designed for the various types of youth audiences. At the same time unless sponsoring agencies or institutions have ascertained the effect of such programs, their impact may be more harmful than helpful.

From both cost-benefit and philosophical-constitutional standpoints, the government role should be limited to ensuring the availability of accurate information regarding the likely consequences of the different patterns of drug-using behavior. With this basic determination in mind, the Commission recommends the following actions are essential to assure the production and the dissemination of accurate information.

First, the federal government should establish a procedure for screening all federally-sponsored or funded information materials for accuracy. The Commission commends SAODAP for initiating such a practice. We note, however, that its current design incorporates a holdover from the policies of the past ; the requirement that information be screened for "consistency with government policy." This requirement, taken seriously, suggests that a conflict might exist between the policy and the truth.

Second, the Commission recommends a moratorium on the production and dissemination of new drug information materials. This step, presently being considered by SAODAP, will enable the federal government to develop necessary standards for accuracy and concept, and allow sufficient time to conduct a critical inventory of presently existing materials. In addition, the government should urge the mass media and all private agencies and groups who produce and disseminate drug-related information to a similar suspension of effort. The National Coordinating Council on Drug Education has already begun to seek private sector support for a moratorium.

The Commission recommends that, after institution of the clearance procedure, a single agency, such as the National Clearinghouse for Drug Abuse Information, should coordinate dissemination of information. This agency should also maintain up-to-date lists and critiques of all information materials and make them available, together with the federal guidelines for accuracy, to state and local governments as well as to interested private groups.

EDUCATION

The cry for more drug education programs in the last decade reflects an enormous confidence in the capacity of our schools to mold behavior. Americans have customarily looked to education as the solution to practically every problem with which they are troubled. Yet, in the words of a professional drug educator : "The drug problem was not created by the schools, and it will never be solved by the schools alone" (Tobin, 1970) .

Drug education, in one sense, is simply drug information transmitted in a school classroom. Unfortunately, too many programs make no more of it than that. Teachers who have received no special training in the task simply read, repeat or pass out materials from other sources, show films, or bring in guest speakers from outside organizations or agencies. Worse yet, the untrained teacher may feel obliged to add his or her own input to the class, contributing misinformation or personal prejudices in the form of facts.

At its best, drug education can be much more than this. First, it is a systematic presentation of information to a particular group of recipients; it is designed specifically for those recipients and attuned to their own level of sophistication, their knowledge and their views. Second, proper drug education employs a teacher trained not only to use the materials at hand, but also to relate to the recipients at a personal level and to use that relationship itself as an educational device. As one expert grandly put it "drug education is a concept placing emphasis upon utilizing the total influences available to affect the individual's social, physical and mental well-being with respect to drugs" (McCune, 1973).

Yet, in the solution of the drug problem, it is not clear that even this form of drug education is an effective preventive approach. In spite of many and varied efforts made thus far, the incidence of drug use for self-defined purposes has continued to rise. This raises the troubling possibility that something basic is wrong with our pedagogy.

In fact, it is possible to speculate that the avalanche of drug education in recent years has been counterproductive, and that it may have stimulated rebellion, or simply raised interest in the forbidden. Historically, this nation has vacillated on the notion that information about potential harm will have a beneficial impact on behavior. Periodically, preventive education has been rediscovered and revived with a great outpouring of public funds, only to be shelved again in the belief that such information serves only to arouse curiosity.

For example, the appearance of opium smoking during the 1870's and 1880's soon inspired multi-state legislation inserting anti-opium courses into the public school curricula. After a short period, these courses were abandoned on the grounds that they had only heightened curiosity in the drug. Fifty years later, the schools were again enlisted, this time to warn against marihuana. In a few years, however, policy makers, particularly at the national level, concluded that the appropriate policy was to deemphasize the problem and avoid whetting young appetites.

Though our society has tried both approaches, we still have no way of knowing which method works best. The impact of drug education programs or other informational activities on behavior has never been evaluated. Whether such programs encourage further experimentation or serve to reduce what might have been a still greater problem remains a matter of conjecture. Yet, despite our ignorance on this fundamental point, drug education and information programs are now receiving increasing amounts of money and classroom time. The faith that "through accurate knowledge of drugs, their attractions and liabilities, drug abuse shall be avoided" was the pervasive theme of all the drug curricula reviewed in a Commission-sponsored study (Boldt, et al., 1973) .

In recognition of ignorance about the impact of drug education, the Commission recommends that policy makers should also seriously consider declaring a moratorium on all drug education programs in the schools, at least until programs already in operation have been evaluated and a coherent approach with realistic objectives has been developed. At the very least, state legislatures should repeal all statutes which now require drug education courses to be included in the public school curriculum. Funneling of even more public funds to drug education—one Congressional committee has tentatively proposed spending $5 billion in five years on prevention in the schools—should be held in abeyance until someone finds out exactly what the money is buying.

In the Commission's view, no drug education program in this country, or elsewhere, has proven sufficiently successful to warrant our recommending it. In many cases, the approaches employed seem altogether inappropriate. Programs have taken the form of lectures by physicians and law enforcement officers, often joined by the "ex-addict" who tells of his experiences. Frequently, the information is exaggerated and inaccurate, designed only to justify preconceived personal biases.

Any concerted effort designed to frighten people away from drugs is doomed to failure. No information at all is preferable to inaccurate, dogmatic information which destroys the credibility of the source. Accurate information, when disseminated through so-called "sophisticated fear" techniques, can also be counterproductive.

To be sure, knowledge about drugs is preferable to ignorance ; but frank dissemination of information, by itself, is not likely to alter behavior. Drug education must assist its clientele to assimilate the information and integrate it into their belief systems. In this sense, education programs should not attempt to manipulate behavior directly, but to influence it directly by communicating accurate, unexaggerated information regarding the relative risks of different drugs and different patterns of use, by dealing credibly with perceived benefits, by promoting an understanding of human needs, and by demonstrating the nature of societal concern about drug-using behavior. In the words of a professional educator, "the basic task of public education today is to help individuals find the means of rational living rather than relying on materials which deal with the symptoms of irrationality" (Luke, 1972).

In the Commission's view, programs oriented solely toward drugs are unlikely to serve us well. Education should integrate information about drugs and drug use, including alcohol and the over-use of legal drugs, into broader mental hygiene or problem-solving courses. In this way, the overall objective of encouraging responsible decision making can be emphasized, without placing the teacher in the position of defending drug policy or of persuading the students to comply with it.

A Commission-sponsored survey reveals an increasing trend toward integrating drug-related instruction into the total school curriculum, wherever appropriate (Boldt, et al., 1973). While drug facts alone probably cannot greatly change attitudes or behavior, presenting them in a context which makes them meaningful would undoubtedly increase their long-term impact. Schools should try to blend drug instructional materials into more general courses. Physical education courses, for example, offer many opportunities to mention the effects of cigarettes, alcohol and other drugs on physical fitness. Courses in biology allow references to the physiological effects of these drugs ; classes in family relations to the impact of their compulsive use on interpersonal relations; courses in social studies, to the historical and social implications of the drug-using behavior.

The Australian Government has already adopted a policy which closely parallels this integrated approach. Their schools transmit drug information indirectly in teaching economics, statistics, biology, science, history, and social studies (Drug Education Subcommittee of National Standing Control Committee, 1972).

The Commission believes that the best response which the school system can make to drug use is not more and better drug education, narrowly defined, but education improved generally. As we pointed out in Chapter Two, education is the career which this nation designates for its young. For some of them, though, it is a meaningless one: a largely barren period of waiting until the community is ready to permit them to assume an adult role.

To be fair, the problem with the education system in this country is not entirely, or even largely, the fault of the schools or the teachers. Society has found in the public school system a multi-purpose tool for a multitude of tasks, only one of which is education. Schools function as a sort of day-care center for parents, as a vineyard where our young are supposed to mature (but sometimes ferment), as a public health clinic, as part of the welfare system, as an instrument of social reform, and, now, as a drug use prevention agency. Sometimes, almost incidentally, they are also a place of learning.

The educational system cannot escape its many-faceted role as a social institution, though it should resist accepting too many more tasks. Society, too, should remember that every new responsibility shouldered by the school system must inevitably impair its ability to perform its primary function. Even with its present handicaps, however, public education in this country is showing that much more can be done. Particularly in the elementary grades, schools are experimenting more and more with innovative teaching methods which attempt to teach the child by meeting his own interests and abilities at least halfway. Educational TV, especially, has shown that the child's native curiosity can be a powerful teaching force, if schools can learn to engage it.

If elementary education succeeds in teaching children the basic lesson—that education can offer them something they want as well as need—the task for secondary schools will be much easier. Nonetheless, junior high and high schools, as well as colleges and universities, have one important obligation that most of them are not now fulfillijig, an obligation that incorporates drug use prevention strategy in its most positive sense. This task is to involve students in adult society in ways which are productive as well as educational. They must provide opportunities for every student to achieve success in some meaningful manner, to see how education can help him meet his own goals of self-fulfillment and to give him immediately a sense of usefulness and self-esteem. We recognize that we are now talking in generalities, but we do not think they are empty ones. Concrete and present examples of what we are talking about can be found in the new opportunities for young people to participate in politics, in work-study pro-grains, in the direct involvement of students in managing their own schools, and in programs for volunteer work, here and abroad. This list, however, is still very small, and it must grow much longer.

Finally, the Commission notes that an effective drug education policy, once developed, should not be limited either to schools or to youth. Elsewhere, we point out the importance of parental behavior as a predictor of youthful behavior. If we are ready to accomplish the task of encouraging responsible decision making, we must broaden the scope of our concern beyond youth. Community-wide adult education programs are no less important than teenage programs. The family can only perform effectively its vital role in dealing with youthful drug use if parents appreciate the complexity of drug-taking behavior, the perceived needs it allegedly fills, and the importance of their own behavior in shaping that of their children.

TRAINING

As we have noted, public schools have often been called upon to play roles that no one institution could possibly fulfill with any degree of competence. The public school is trusted to handle any problem, whether economic, social, political or ideological, as part of its normal responsibilities. We believe that this overload of the educational system must stop. Accordingly, the Commission recommends a community-wide strategy, in which all members of a community, and not merely the schools, acquire information about drug use, so that all can work at improving the situation.

At the present time, however, programs for training people in drug use prevention are not given sufficient emphasis. Training of the professional and the education of the layman has to this point been hit and miss. Not surprisingly, in response to the publicized drug "crisis," teachers, community leaders, government and other supervisory personnel, including the military, are clamoring for participation in drug conferences, workshops and training programs.

It is imperative that we take an approach which encompasses broader kinds of prevention techniques, utilizing the resources of the entire community. The recipients of training, for example, should include not only the mental health professional but the local policeman as well, for both have opportunities to identify pending problems and lend perspective to the community concern.

The emphasis thus far has been on teachers or on so-called "experts." Research, though, indicates that students do not regard all experts or teachers as equally believable. They tend to trust medical professionals and ex-users (though the latter may not always have relevant information) and to distrust law enforcement agents, clergymen, and guidance counselors, who are suspected of pushing the "official" view (Brotman and Suffet, 1973) . Similarly, some teachers are especially "approachable" by students and can be very influential in dealing with their problems. Others are less so.

Curiously, in the search for credible sources of information, drug education has ignored the resource of the students themselves. Many educators remark that students know more about drugs than teachers, but relatively few explore the implication that students should produce and disseminate knowledge and not merely perform the role of a passive audience. Active student participation enables the student to assume responsibility; it also employs peer influence in the educational process (De Lone, 1972) .

A Commission-sponsored study indicated particular concern that public school personnel are not sufficiently trained to recognize potential or present high-risk users (Douglas, 1973) . Public funds earmarked for "teacher training courses" have rarely included counseling personnel, who often have extensive contact with the youthful school population (Wald and Abrams, 1972) .

Similarly, an examination of social service agencies conducted for the Commission reveals a lack of personnel trained to recognize early signs of problem drug use (Greenleigh Associates, 1973) . Social service agencies tend to be staffed by professional social workers whose education traditionally does not include diagnosis of drug problems. These agencies reported a serious need for staff training in dealing with drug use ; they also indicated a need for guidance on when to intervene in the use process and whether to intervene in the case of adults as well as young people. Health-care personnel, too, require special training in both drug use prevention and treatment.

Training programs are beginning to appear, but their size and scope remains inadequate. At present, the National Institute of Mental Health has six regional centers 59 in addition to the National Training Center in Washington, D.C. Recently, the thrust of these programs has shifted from developing "community statesmen" to teaching treatment skills. This change is significant, but the centers must stress training in prevention techniques and identification of high-risk characteristics as well. The Office of Education has also established eight regional centers °° charged with training selected teams of community residents and educators, who then return to their communities better equipped to mobilize local resources in providing drug education and to establish community-based drug programs, including treatment and rehabilitation programs.

Both the National Training Center set up under SAODAP and the regional programs should be expanded to meet present demands. As much as possible, expansion should occur through enlargement of current programs. Present facilities should be fully utilized. Moreover, training is often a part of an integrated prevention-treatmentrehabilitation program, and too great a dispersal of training centers might result in smaller programs becoming subsumed in the other drug functions.

Finally, more people in training programs will do little good if the training is incomplete. To date, official SAODAP policy tends to equate prevention strategy with the treatment of those enrolled in rehabilitation programs. As we have indicated, new approaches in prevention techniques still need to be developed.

THE MEDIA AND DRUG-USE PREVENTION

When disapproved use increases, officials may sometimes search for targets which offer opportunities for visible, decisive action. Not surprisingly, then, recorded rock music, thought by many to glamorize the so-called drug culture, suddenly became an issue of public policy. In March 1971, the Federal Communications Commission issued a public notice "pointing up" that the broadcast management had a "duty to exercise adequate control over the broadcast material presented over his station." The occasion for this reminder, said the FCC, was a number of complaints to it concerning record lyrics that tended "to promote or glorify the use of illegal drugs such as marihuana, LSD, `speed,' etc." The notice added : "In short, we expect broadcast licensees to ascertain, before broadcast, the words of lyrics of recorded musical or spoken selections played on their stations" Federal Communications Commission, 1971a).

This notice was widely interpreted, in the words of the dissenting Federal Communications Commissioner Johnson, as an "effort ... to censor song lyrics the majority disapproves of." A month later, the Commission issued a second notice disclaiming any such intention : it emphasized that choice of material was "a matter for the licensee's judgment," so long as he knew what he was selecting (Federal Communications Commission, 1971b) . A third notice, in August 1971, again denied censorship and stated, in a footnote, that it had not imposed any "pre-screening requirement for each record" (Federal Communications Commission, 1971c) .

Despite such clarifications, the FCC's action seems to have had the chilling effect which the dissenting Commissioner had predicted. The broadcasters, naturally concerned about renewal of their licenses, refused to air any recording which seemed even remotely related to drugs. A study of rock lyrics undertaken for the Commission indicates that radio stations refused to play some records which had nothing to do with drug use and some which were actually designed to discourage it. Many other banned recordings were simply descriptive, and clearly distinguished among various kinds of drug-related behavior (Feinglass, 1973). The entire matter is currently before the federal courts.

Concern about proprietary drug advertisements, especially those on television, is another example of public belief that the media are exercising a subtle, undesirable influence on attitudes toward drug use. In another section, the Commission explores the extent to which commercial advertising may be preaching a drug-using response to daily stress. At this point, we only want to emphasize that, whatever the dangers of information which encourages use, the dangers of government suppression of such information are far greater.

The extent to which mass media affect behavior is one of the oldest questions in media research. On the one hand, available data do not support the conclusion that mass communication frequently has a decisive effect upon the behavior patterns of its audience. On the other hand, many observers, including practical men of business as well as students of communications theory, believe that the media are highly influential, even if measurement of their impact remains an imprecise art (Kramer, 1973).

A massive effort on the part of the federal government and volunteer advertising agencies was undertaken in 1967 to focus on the drug issue. Large expenditures of human and financial resources were devoted to anti-drug commercials to "call attention to the problem and create awareness." In early 1970, a new three-year media drive was undertaken to "unsell" the concept that drug-taking is fashionable and to change basic attitudes toward the taking of drugs.

Despite this massive effort on the part of the federal government and the volunteer advertising agencies, there has been little government-sponsored systematic evaluation of the effectiveness and impact of the broadcast media in communicating these anti-drug messages (Kramer, 1973). Preliminary testing evaluated the effectiveness of these announcements on two of the five target groups (pre-teenagers, youth through college, adults, the inner city, the military), but post-testing was not possible as the agencies had no control over when these public service announcements would be aired by the broadcaster (Compton Advertising, Inc., 1970a, b).

An extensive evaluation of these public service announcements should be undertaken to determine the effectiveness of all media in disseminating drug information and to determine which groups are appropriate target audiences. Recent critics have asserted that the anti-drug commercials were broadcast in a shot-gun fashion with little regard paid to audience-viewing patterns. For example, research revealed that over 90% of the drug abuse commercials observed during several viewing samples were broadcast during times of typically lower audience attendance (Hanneman et al., 1972a).

Whatever the impact of the media on drug use, however, they are only one of many channels of communicating drug messages, and according to other data, hardly the most important. Families and peer groups, by their words or examples, seem the most potent agents of communication where drug using behavior is concerned. Drug use among the young is directly correlated with parental use of chemicals and alcohol, as well as with alcohol and tobacco use among peers (Ianni, 1973 ; Louria, 1971) . When they want specific drug information, nonusers most often rely on professional sources while users usually go to their friends (Hanneman, 1972). We have already noted that antidrug messages in the media appear to have only limited effect even in shaping attitudes. In the absence of research, there seems no basis 0to assume that pro-drug messages are substantially more influential, especially when compared to the impact of family and friends.

Media management and advertisers should exercise great responsibility and discretion in presenting material that might encourage someone to use psychoactive drugs. The Commission strongly believes, however, that any censorship should be left to the private sector itself.

OTHER PREVENTION STRATEGIES AND TECHNIQUES

Prevention activities should not be limited to information, but should concentrate on satisfying important needs of the target populations. Similarly, prevention should not be limited to schools, pamphlets, and spot announcements. Again we emphasize that prevention strategies must take advantage of other institutional forces affecting the behavior of the at-risk population. For example, the "tyranny" of "peer pressure" has been indicted time and time again ; yet, few have considered how peer example can be used positively as well. Some communities have begun to utilize underground peer counselling and similar street-oriented services. Although these programs are even less amenable to rigorous evaluation than more formal ones and have their own special risks, the Commission feels that they might offer substantial opportunities for the overall preventive effort.

One such service, a warning system to minimize the dangers attending use of street drugs, is already being provided in several cities. Plainly, the hazards of these substances do not keep many people from using them. Experience does indicate, however, that reliable information about the purity of street drugs can lead the involved populations to avoid the suspect substances. The argument against such a warning system is that it would appear to condone use. On the other hand, its proponents contend that humanitarian considerations are more important and that such a system does reduce the risk of overdose, adulteration and infection. Drug analysis projects might have the added benefits of bringing users into contact with other prevention and treatment programs and of demonstrating to them that the illicit drug market is not the benevolent institution many think it is. Reports by warning systems consistently show that the buyer does not always get what he bargained for. For example, a recent analysis of 16 street samples by the Associated Students of the University of Oregon revealed that five contained no psychoactive element and five others were drugs other than those alleged (mostly LSD).

While the Commission does not believe the government should sponsor such programs, we think they can serve useful purposes in areas where the incidence of drug use is substantial. Accordingly, the Commission recommends that the government not interfere with private efforts to analyze the quality and quantity of drugs anonymously submitted by street users and to publicize news about market patterns and dangerously contaminated samples.

A recent development related to the warning system is the "hot line," an information and referral service which is free, anonymous and always available. Since it is extremely important to encourage persons in need to seek assistance voluntarily, the Commission generally favors hot lines. Yet, many of these programs do far more harm than good because they are staffed by untrained people who give out faulty and sometimes dangerous advice. The Commission recommends that local communities, with federal assistance and perhaps regional cooperation, should ensure that "hot line" information programs have qualified people running them and that the information they dispense is reliable. To maintain their credibility, though, hot lines should not be connected with enforcement agencies, should be staffed wherever possible by young adults, and should avoid making value judgments on drug use.

The Commission encourages prevention techniques, like "crisis intervention" programs, which encourage problem users to seek help. We note our opposition, however, to coercive identification techniques, unless society has already established a legal basis for asserting control over a particular individual. In designing and implementing prevention policies, the government should strive, in intent and appearance not to abridge the personal liberties of target groups. Specifically, the Commission recommends that the government not support, sponsor or operate programs which compel persons, directly or indirectly, to undergo chemical surveillance, such as urinalysis, unless the person is participating in treatment services, is a prospective or actual public employee, is charged with a crime or is a member of the military. Even in the above circumstances, information obtained should be confidential. Recent proposals to subject elementary, secondary school or college students to routine or random urinalysis contravene fundamental precepts of this society.

Once the society has formally asserted control, through appropriate legal process, over a person who has consumed prohibited substances, an appropriate response may be to refer the person to "drug dependence prevention services" for the reasons and in the manner specified earlier in this Chapter. Any person required to participate in such programs should be sent to those services best suited to his specific needs.

The Commission recognizes that this proposal parallels those of other Commissions which have dealt with problems of youth ; for example, the President's Commission on Crime and Administration of Justice recommended in 1967 that local communities establish "youth service bureaus" as mechanisms for referral and disposition of youths apprehended by the police. We have been apprised that the development of such services is still in the primitive stages; many major communities have failed to give the matter serious study. We urge them to do so now, and to integrate what we have called drug dependence prevention services into these broader youth services programs. As we conceive them, the two activities would be co-extensive in design as well as in practice.

The Commission believes that a sound prevention policy must encompass all those institutions and services necessary to provide a network of support for the targeted, at-risk populations. Accordingly, the Commission recommends that drug dependence prevention services should include educational and informational guidance for all segments of the population; job training and career counselling; medical, psychiatric, psychological and social services; family counselling; and recreational services.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

The Commission cautions that prevention of all intensified or compulsive drug use is an ideal, but unachievable goal. There will always be an irreducible minimum of predisposed individuals who will respond to a set of adverse conditions with what one of our consultants called the "autoplastic solution"; a self-changing, escaping response, such as compulsive drug use (Korn, 1973). However, this society, with its abundant human resource services, can do much better than it is doing now to modify the predisposing conditions and to prevent the escalation of drug use to disruptive patterns.

Achievement of society's secondary objective of discouraging the use of drugs for circumstantial, experimental and recreational purposes ultimately depends upon a significant change in contemporary attitudes. In order to turn substantial segments of this society away from the use of drugs for enjoyment, temporary mood alteration, group identification, escape and protest, concerted institutional effort is needed to provide more satisfying and constructive alternatives for meeting those needs.

With regard to youthful drug use in particular, we can only strive to prevent youthful experimentation and involvement by correcting the weakest component of our national life; the way we treat our children. Listening carefully to young people has always been the first step in determining how to guide them. Some important recommendations on this subject were made by the 1970 White House Conference on Children and the Joint Commission on Mental Health and Illness of Children in May 1970. They have largely been ignored.

Long-term prevention strategies must deal with these amorphous and elusive issues. In the short term, however, the Commission believes that the most useful strategy is to focus our efforts on preventing intensified and compulsive use of drugs, both of which we classify under i the general heading of drug dependence, by particular high-risk populations. Prevention policy should be concentrated on those groups which appear to be most vulnerable to drug dependence by virtue of identifiable social conditions. In this connection, we emphasize the absence of reliable etiological research to permit us to identify these high-risk populations. The conduct of such research is a matter of the highest priority.

An important feature of a sound prevention policy is that government take the initiative through prospective programs rather than reacting after the fact to changes in use patterns of particular drugs. For this reason, the Commission recommends that the primary responsibility for designing a prevention strategy and operating appropriate programs reside at the state and local levels. Each state should establish a comprehensive, state-wide drug dependence prevention program including a full range of prevention services attuned to the needs of local communities and designed to reduce the likelihod that an individual or class of individuals will become drug dependent.

The Commission further recommends that the federal government fund such services through block and formula grants to the states, and sponsor basic research in the prevention area. The federal government should also use discretionary funds to support innovative and experimental programs, as well as programs in communities receiving insufficient aid from the state.

The state should assist local communities and institutions (such as universities, business and youth groups) to develop prevention services attuned to their respective needs. Specifically state agencies should help communities to identify target populations, select appropriate services and referral procedures and develop evaluative criteria.

The Commission recommends that community-based prevention services be initiated only after local policy planners have assessed the needs of their particular target populations. For example, prevention services provided to drug users referred from public health or criminal justice agencies should be quite different than those provided to a general high school audience or an audience composed of parents.

Finally, we recommend that each community give high priority to the development of crisis-intervention services for particular populations as part of its overall prevention services.

°' For convenience, we will segment these activities into the conceptual areas of training, information and education. Training will refer to efforts to increase knowledge and skills of teachers, police, supervisors, and other caregivers who are then expected to pass on their information to target populations. Information programs will refer to the production and dissemination of drug-related materials, no matter what the intended audience or the medium. Education will refer narrowly to formal programs in schools and other institutions whereby information about drugs is systematically communicated to a particular clientele. Thus, most education programs presumably would be making use of previous training efforts and information activities

58 Some school districts which have pressed school guidance counselors or physical education teachers into service as the drug education expert, requiring that they "do something" about drugs in the schools ; these persons are generally unaided by guidelines, criteria, or effective supervision. Other districts, however, have contracted with outside consultants to develop pretested curricula materials and measure their effectiveness.

In Oakland, California ; New Haven, Connecticut ; Miami, Florida ; Chicago, Illinois ; New York City and Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.

B0 In Oakland, California ; New Haven, Connecticut ; Washington, D.C. ; Miami, Florida ; Chicago, Illinois ; Minneapolis, Minnesota ; Long Island, New York and San Antonio, Texas. There are also three SRS training programs in Miami, Florida ; Oklahoma City, Oklahoma and Oakland, California.