| - |

Drug Abuse

IV TREATMENT AND REHABILITATION

The history of the treatment and rehabilitation of drug-dependent persons has been and continues to be a series of largely unsuccessful efforts to separate opiate-dependent persons from their opium, morphine and more recently, heroin. For at least 200 years, society's attitude toward such dependent persons has oscillated between the belief that their dependence is simply an example of willful self-indulgence deserving contempt and sanction, and the concept that it is a pathologic condition meriting compassion and treatment.

AN OVERVIEW OF THE PRESENT RESPONSE

Consensus about the proper way to deal with drug dependence usually lasts until its ineffectiveness becomes unmistakable. In the 1920's, after several decades of futile searching for a physical cure, the moral view of dependence prevailed, almost by default, among policymakers, the medical profession, and consequently the public. Today, the incidence of dependence and the substantial recidivism among drug offenders have demonstrated the limitations of a predominantly punitive response, the country has looked anew for a therapeutic solution. In the National Survey conducted by the Commission in 1972, 55% of the respondents said that mandatory treatment was the appropriate way to handle a heroin user the first time he was apprehended; only 16% felt a first offender should go to jail.

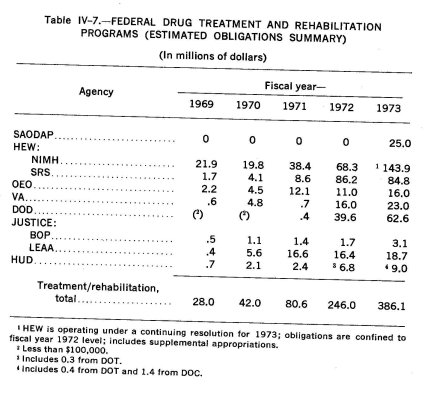

This apparent change in public attitude parallels the new direction of public policy. Over the past four years, federal expenditures for drug treatment and rehabilitation have increased nearly thirteen-fold, totalling $386 million in fiscal year 1973 and comprising almost half the entire federal durg abuse budget. Together, federal and state governments have appropriated roughly $650 million for drug treatment programs in fiscal year 1973. (For federal appropriations, see Table IV-7.)

During the years 1967-1972, Congress enacted four pieces of drug treatment legislation. In the same period, 17 states passed laws setting up voluntary treatment programs. Forty-four states have now designated some official or agency to coordinate drug rehabilitation efforts.

While the Commission favors a therapeutic response to drug dependence, we recognize, nonetheless, that this condition is only partly an illness, and therefore, only partly responsive to traditional therapeutic techniques.

Uncertainty About the Illness

Though the medical professions have been studying and treating the condition of opiate dependence for more than a century, the nature of the affliction is still an enigma. The debate continues today, for example, whether opiate dependence is primarily a physical or psychological phenomenon. Methods of physical medicine can be employed quickly and effectively against the physical component of opiate dependence; however, they are of little assistance in dealing with the psychological reinforcement component and in preventing resumption of use.

On the other hand, the techniques of psychiatric medicine and clinical psychology have not often succeeded in solving the relapse problem. This fact has led some observers to hypothesize a basic physical cause after all ; a yet undetected biochemical or physiological alteration caused by initial episode of dependence which creates an enduring and unextinguishable "hunger" for the drug and makes the person a biological anomaly (Dole, 1969).

Confusion about the disease has understandably resulted in confusion about its treatment. The latter is compounded by the fact that no method of treatment has proven generally effective. As one clinician has observed :

It is a clinical truism that the less effective our treatment methods

for any given syndrome, the wider the diversity of opinion on how

best to approach it. So it is with compulsive drug use (Jaffe, 1972).

Uncertainty About the Objective of Treatment

Treatments for drug dependence differ not only in method, but also in objective. All contemporary drug treatment programs espouse the elimination of dependence as their ultimate, if not immediate goal. In fact, though, long-term methadone maintenance treatment seems to rest on the theory that some dependence may be incurable, and that the function of treatment is to restore "normal" social functioning Until recently, the view was widely shared that the patient's behavioral maladjustments stem from his drug dependence, and that use must end before social rehabilitation is possible. Contemporary maintenance programs reflect the contrary view, holding that drug dependence is but one symptom of a more basic psycho-social problem and that until this problem is solved, efforts to end dependence will generally fail. From this perspective, the treatment aims to stabilize use so that it will not interfere with rehabilitative efforts.

Occasionally, other goals have been propounded. One is simply to relieve the physically-dependent user's suffering, by making adequate doses of his drug available to him under conditions which minimize the secondary health problems of use. Another goal may be to minimize the antisocial behavior attending compulsive drug use, either by making the drug available to the user, or isolating him from the community, or both.

Diversity of Method

Uncertainty about the causes and nature of dependence, and about the goal of treatment has engendered a wide variation in method. There is of course the distinction between treatment which rapidly withdraws the user from his dependence on a drug and that which maintains the dependence, perhaps substituting another drug. Treatment methods also vary according to whether they are inpatient or outpatient ; whether they occur within the geographical confines of the patient's community or remove him to some entirely different location; whether they employ legal coercion as a means of initiating treatment or assuring continued participation ; whether they are selected in accepting patients or take all who apply or are referred to them ; whether they employ psychotherapy, group therapy, counselling, and vocational rehabilitation.

Recently, there has been an increase in the number of treatment programs which are outpatient, community-based, voluntary, nonselective in entry, and capable of furnishing a wide variety of treatment methods and modalities, including both maintenance and abstinence regimens. In mid-1972, over 20,000 patients were being treated in ambulatory multi-modality programs. It has been estimated that by the end of 1973 patients in such program will number more than 100,000 (Brown, 1973) .

These programs have proliferated even though their effectiveness has not been fully demonstrated, primarily because they are inexpensive compared to programs requiring hospitalization or segregation from the community. Finding that each of the current treatment methods works for different subgroups of opiate-dependent persons and none is universally effective, the best that treatment programs can do at the present time is to offer a range of modality alternatives.

Despite the confusion about treatment of opiate dependence (and alcoholism), knowledge in this area far outdistances what is known about treatment of other drug-dependent persons. Medical procedures have been developed for detoxifying persons dependent on barbiturates, which is a considerably more difficult and risky process than withdrawing opiate-dependent persons. However, no specific treatment exists for persons psychologically dependent on drugs such as amphetamines, cocaine and even cannabis, all drugs which do not induce physical dependence. Emergency care may assist persons suffering from the acute effects of single overdoses, but the only process now available to assist persons psychologically dependent on these drugs is treatment of any underlying personality disorder or psychiatric illness.

The confusion which still characterizes contemporary treatment of drug dependence raises a central question which cannot be avoided simply by labelling the condition an illness. Perhaps medical science has been unable either to explain the condition or to develop a substantially effective response to it because drug dependence is not really an "illness," but only a pattern of human behavior particularly resistant to the usual forms of social control. In less prosaic terms, drug dependence may be primarily an illness of the spirit whose "cure" is beyond the powers of medicine. Before confronting this hypothesis and its implications for public policy, it will be instructive to explore the history of drug dependence and its treatment and to examine more closely the various therapeutic methods currently employed.

HISTORY OF THE TREATMENT OF OPIATE DEPENDENCE

Medical literature described the physical symptoms of opiate withdrawal as early as 1701, but a century passed before physicians realized that opium dependence differed in important respects from habitual use of wine or tobacco (Sonnedecker, 1963) . The earliest well-known account of this condition and its treatment is not by a doctor but by a writer, Thomas de Quincy. His Confessions of an Opium-Eater, published in 1821, described in detail his dependence on the drug and his self-devised apparently unsuccessful, attempts to cure it by gradual reduction in dose (Brill, 1973) .

The medical profession remained relatively uninterested in the phenomenon of opium dependence until the last half of the 19th Century. By that time morphine, first isolated in 1803, had become widely used in proprietary medicinal preparations and in medical practice, and was often administered through hypodermic injection, a practice which became increasingly common in this country after the Civil War. The use of opium and morphine in the streets, beginning in the last decades of the century, attracted considerable public and professional attention to the habit-forming properties of these drugs.

1870-1900: The Early Years

During this period, treatment for the opiate "habit" was private and usually involved withdrawal accomplished either gradually, by small, but continuing reductions in the amount of the drug taken, or rapidly, by complete cessation of use within three to eight days. The rapid withdrawal process was often quite hazardous for the patient, not so much because of the rigors of withdrawal itself but because of the effects of non-opiate drugs generally administered by the treating physician to suppress abstinence symptoms (Kolb, 1963; Musto, 1973a,b).

The large majority of dependent patients, however, survived their treatment, and after an apparent separation from the drug, they were considered cured. Physicians who specialized in treatment of morphinism began to notice the problem of relapse,38 but apparently most of them thought it resulted from a failure to deal properly with the withdrawal symptoms. Their solution was to look for new assortments of drugs to administer during the period of withdrawal (Brill 1973).

From a contemporary perspective, 19th Century treatment methods appear to have been primitive and many seem to have been harmful as well. Few of them reflected an appreciation of the psychological components of drug dependence, and no one had designed a method of dealing with this part of the problem. Attempts were rarely made to follow up patients who had been withdrawn to ascertain the success of therapy.

Moreover, during the period 1870-1900, most opiate-dependent persons never received special treatment at all. Clinics and sanataria were largely private and profit-making; only those of some means could afford their services. The rest went to a general practitioner or took patent remedies, the most popular of which were opium-based. Either way, the result was usually to maintain dependence, rather than to cure it (Brill, 1973) .

1900-1915: Years of Optimism

Increasing concern about morphinism within the medical profession and the legislative community fostered attempts to prevent new cases of dependence by restricting the availability of dependence-producing substances and revived interest in discovering a medical technique for curing those already dependent. With regard to availability we have already noted the progression of state prohibitions during the early years of the century and the pressure for federal legislation culminating in the passage of the Harrison Act in 1914.

These developments paralleled a growing confidence within the medical profession that dependence was curable. Drawing upon analogies with infection, many: physicians insisted that the condition had an organic basis which could be altered through proper withdrawal techniques. Dozens of sanataria for alcohol and drug-dependent persons were by now scattered across the United States, and the sanitarium operators wrote extensively on dependence, promoting their particular treatment methods. With the enactment of the Harrison Act, many policy makers were apparently convinced that a cure was imminent (Musto, 1973a,b) .

1915-1930: Confidence Wanes

After the passage of the Harrison Act, the treatment of opiate-dependent persons, formerly a private matter, gradually became interwoven with the legal policies regulating the availability of dependence-producing substances. Within a few years the organic theories of dependence had been discredited, triggering bitter debates regarding whether dependence was a disease after all, and whether maintenance of the opiate-dependent person was legally permissible. Though ostensibly a revenue measure, the Harrison Act had the objective of ending all sales of proprietary preparations containing large amounts of opiates or cocaine and of restricting the ultimate distribution of these drugs to registered physicians or dentists acting "in the course of ... professional practice only."

Whether Congress also intended the law to prohibit doctors' prescribing maintenance doses to dependent patients is still a matter of debate, but the Treasury Department so interpreted the law, even though the first major decision on the Harrison Act by the Supreme Court undercut this construction.39 The federal government brought numerous indictments under the Act against physicians who were maintaining patients. Some doctors were plainly violating the law by distributing large amounts of opiates for the asking ; others, however, were acting in accord with their good faith belief that maintenance was the only useful treatment for dependence. Indiscriminate enforcement of the law succeeded not only in eliminating the notorious "script" doctors, but also in deterring the few private physicians who might have been willing to treat opiate-dependent persons (Livingston, 1963) .

After 1919, almost no legitimate source of opiate drugs remained to the dependent user. Law enforcement officials felt that cutting off the supply of drugs would force dependent persons into treatment and that, once withdrawn, they would have no opportunity to relapse. Perhaps this was true for m4)st of the individuals who had developed dependence in a therapeutic setting, but there were thousands, particularly in larger cities, who had become dependent on the streets and who turned not to treatment but to the illegal market.

To deal with this new problem, the Treasury Department in 1919 encouraged local communities to establish temporary clinics for the maintenance of opiate-dependent persons on the theory that these facilities would serve as feeders for drug-free institutional treatment or would at least attempt gradual reduction in dosage, working toward an eventual withdrawal of the drug. Forty-four clinics were established, although their administrators were often not as sanguine about eventual abstinence, aiming instead to supply opiate-dependent persons with maintenance doses in order to relieve their suffering, and to prevent their resorting to the illicit market to purchase their drugs and to criminal activity to pay for them (Butler, 1922) .

Some clinics claimed success in withdrawing patients ; others apparently did not try, and several became notoriously careless in their distribution of drugs. The leakage of drugs from the poorly run clinics, coupled with repeated condemnations of ambulatory maintenance treatment by the American Medical Association, apparently caused the Treasury Department to withdraw its support. In 1920, the Department began to order the clinics closed, and by 1925 the last one, in Knoxville, Tennessee, had ceased operation (Brill, 1973; Musto, 1973a) .

With the demise of the public clinics, the first era of social response to drug dependence, with its emphasis on private medical treatment, came to an end. The new emphasis was on prohibition, not only of distribution of opiate drugs, but also of their use. In a sense, the new policy may actually have solved most of the drug problem existing at the time. The danger of medical dependence, which inadvertently resulted from use of prescription drugs or proprietary medicines, was drastically reduced. The 250,000 cases of dependence estimated to exist in 1914 had probably diminished to less than half that number a decade later. The chronic use of cocaine had also been reduced considerably by the end of the decade (Livingston, 1963 ; Brill 1973) .

As the old drug problem faded, though, a new one began. In place of the declining population of middle-aged, predominantly female medical dependents, there appeared a growing number of young users, almost always male, largely urban, and drawn disproportionately from minority ethnic groups, who tended to prefer heroin to morphine. This pattern had first become noticeable in New York around 1912, and by the late 1920's predominated in most cities. Another aspect of the emerging pattern was intravenous injection of the drug, a practice which apparently originated in Egypt in the late 1920's (Brecher. 1972 ; Brill, 1973) .

For a while, there was virtually no treatment available either for the remnants of the old addict population or for the recruits to the new. Many doctors who employed the rapid withdrawal technique in the past had become convinced, by the tendency of many chronic users to relapse again and again, that dependence was not a disease, but instead a deficiency of will. Other physicians, who recognized the importance of the psychological component of dependence, may have given up because the government, supported by a series of Supreme Court decisions, did not permit maintenance,'° and the problem of relapse after withdrawal inhibited medical efforts to deal with underlying emotional difficulties. Withdrawal followed by long-term confinement, a third possible way of dealing with the dependent patient's psychological problems, was difficult for individual practitioners to arrange. The growing association between dependent persons and criminal activity made hospitals reluctant to accept them as patients. Even if such facilities had been available to the dependent population, few of them could have paid for such treatment, anyway.

The year 1930 may be taken as the close of the era of therapeutic optimism with regard to opiate addiction. It had been increasingly difficult since World War I to generate enthusiasm for an addiction cure, and within a decade the full weight of clincal medicine was against any such claims (Musto, 1973a) . Everything had been tried and everything failed; the relapse rate was appalling. When Congress authorized the establishment of two drug treatment hospitals in 1929, the primary reason for federal action was not to provide treatment, but to segregate from other prisoners the large number of opiate-dependents who crowded federal penitentiaries. Yet in the debate over authorization, the warm hope was expressed that these hospitals would devise an effective treatment or make a new discovery which would solve the dependence problem.

1930-1960: The Dry Years

The first of the federal drug treatment hospitals, called "narcotic farms", opened at Lexington, Kentucky, in 1935, 21 years after passage of the Harrison Act ; the second opened at Fort Worth, Texas, three years later. The location of the two facilities, particularly the one in Kentucky, and the euphemistic term "farm" reflected a faith in the therapeutic value of rural life, fresh air, and removal of the patient from the environment which had fostered and reinforced his drug-using behavior. Although designed primarily for the incarceration of federal prisoners who were drug dependent, the two facilities also accepted voluntary patients and the latter class soon accounted for three-quarters of all admissions (Isbell, 1963; Brown, 1973).

During the fallowing three decades, there were about 100,000 admissions to the two federal hospitals, though a significant number of these were former patients returning. The facilities withdrew all patients through decreasing doses of morphine (replaced by methadone after World War II). Withdrawal was followed by a period of inpatient aftercare supposedly lasting several months. Voluntary patients at the two facilities, however, were free to leave whenever they wanted, and once withdrawn, most did not stay for the rest of the treatment. Follow-up studies indicated that nine out of 10 of these patients soon relapsed into drug use, and the hospital staff sought a technique for compelling the voluntary patients to remain at the facility for aftercare. An attempt to do this by making applicants agree to remain until released failed when the courts refused to enforce the agreement. The Lexington staff then devised a more ingenious method; they refused to admit voluntary patients unless they pled guilty to a drug offense before a local state judge, who would then give the patient a probationary sentence, conditional upon his remaining in treatment. There is no indication, though, how often this was done or how well it worked.

The two federal hospitals remained the only major drug dependence treatment programs in the country, until 1952, when the State of New York opened Riverside Hospital for the examination and care of opiate-dependent juveniles. The Riverside program involved an initial period of hospitalization, lasting as long as 18 months or more, after which the patient was placed in outpatient care. Under the Public Health Law of New York, the hospital had actual custody of its patients for a period not to exceed three years; generally treatment was continued for the full three-year period (Livingston, 1963). Riverside was closed in 1963, after a formal study indicated that over 95% of the patients relapsed after release.

During the period from 1930 to 1960, some drug-dependent persons received treatment in regular state mental hospitals. The laws of 34 states authorized such treatment, and in New York and California, at least, some drug-dependent persons actually became patients in mental health facilities (Brill, 1973) . No studies indicate how many dependent persons in all were sent to mental hospitals, how they were treated, or with what effect. There can be little doubt, however, that the number was small and most drug-dependent persons rotated between street and jail, with perhaps a stint or two at one of the federal hospitals.

The Sixties : Society Turns to Therapy Again

The inability of the predominantly criminal approach to reduce or contain drug dependence became increasingly apparent during the 1950's, particularly after punitive policies reached their peak in 1956. The American Medical Association and the American Bar Association established committees to look into drug policy and increasing professional interest triggered a White House Conference on Narcotic and Drug Abuse in 1962 and the appointment of a Presidential Commission the following year. As new interest in a therapeutic approach grew, new treatment methods began to emerge.

In 1959, a recovered alcoholic named Charles E. Dederich established a residential community for drug-dependent persons in California. The community, called Synanon, employed confrontation group therapy modeled after that used in Alcoholics Anonymous. The treatment method was almost exclusively psychological, though no professional psychologists were in the program. The members confronted each other in group sessions, applying positive reinforcement to drug abstinence behavior and negative reinforcements upon relapse.

The community was not designed to deal with large numbers of drug-dependent persons at one time, and many of those who entered left because of the rigors of the confrontation method. The dramatic transformation of those who stayed, however, caught the public imagination. Synanon represented the first major innovation in drug treatment since safe, fairly painless withdrawal techniques had been developed at Lexington. Other communities, patterned after Synanon but often differing in important details, sprang up. Both the therapeutic community and group therapy were soon established as an important mode and method of treatment.

In 1961 and 1962, respectively, legislatures in Cailfornia and New York established state-wide treatment programs for opiate-dependent persons. These statutes adopted the Lexington model but aimed to perfect it by making aftercare compulsory. In both states, the laws authorized civil commitment of opiate-dependents, as well as diversion of drug-dependent defendants from the criminal justice system. Treatment was to involve withdrawal, psychiatric counselling, and group therapy. The regimen began with varying periods of mandatory hospitalization, even for voluntary entrants, and continued through supervised outpatient aftercare.

Unfortunately, an excess of control over care marred both programs. The treatment facilities were either converted correctional institutions, or were prison-like in nature. In California, the Department of Corrections actually ran the treatment program. Defendants shied away from the treatment alternative, because it could mean a longer period of incarceration than a jail sentence; in California, compulsory drug treatment could last as long as ten years while the penalty for use was no more than a year in jail, and the penalty for possession ranged from two to ten years. Finally, the results of both programs were disappointing. As in the case of Lexington and Riverside Hospital before them, both programs were thought to have extremely high patient relapse rates.41

Synanon and the California and New York commitment programs were contrasting methods of achieving long-term abstinence by dealing with the psychological component of drug dependence. In 1964, however, drug-based therapy was revived when two doctors in New York City, Marie Nyswander and Vincent Dole, began an experimental maintenance program employing methadone, the drug Lexington used in its withdrawal technique. For their experiment, Doctors Dole and Nyswander carefully selected 22 heroin-dependent persons, all volunteers over 20 years old, who had been dependent for at least four years, were free of any severe psychiatric disorders or medical complications, and had previously failed at drug treatment. They hospitalized their patients and administered methadone in oral doses, once a day, gradually building to a stabilizing dose of between 80 and 120 milligrams. After stabilization, the patients were released and permitted to return periodically to the clinic for medication while receiving individualized counselling and support services.

Doctors Dole and Nyswander were amazed by the dramatic success of their experiment. The patients, now stabilized on methadone, no longer seemed preoccupied with their drug taking. Anti-social behavior measured by arrest and incarceration, dropped steeply ; at the same time, there was a substantial increase in the patient's social productivity, measured by the number employed, in school, or enrolled in vocational training. Most significant, perhaps, all the patients stayed in the program voluntarily. Encouraged by this success, Doctors Dole and Nyswander expanded the program, enrolling about 4,000 patients over the next three years. In 1967, an independent evaluation of the program, conducted by Columbia University School of Public Health, found that 80% of the patients had remained in the program and showed marked improvements in social functioning as well.

Following the Dole-Nyswander experiment, the federal government permitted the establishment of other experimental methadone maintenance programs, and further successes were recorded. Subsequent experiments demonstrated that the initial hospitalization period was unnecessary, reducing the expense of the program and freeing urgently needed hospital beds. By 1972, methadone maintenance had become by far the largest single modality of treatment for heroin dependence, with an estimated 70,000 patients (Brill, 1973) .

In 1966, while methadone maintenance was still in its experimental stages, Congress passed the Narcotic Addict Rehabilitation Act (NARA). Introduced as a major commitment to the therapeutic approach to dependence, NARA was in part an attempt to undercut the mandatory minimum penalties of the 1956 Act by offering a treatment alternative to some drug-dependent offenders.

The first two titles of NARA established a federal version of the New York and California programs; Title I authorized pre-conviction diversion to treatment of a highly restricted class of federal offenders, and Title II provided for treatment as a sentencing alternative for a slightly larger class. Title III provided for voluntary and involuntary civil commitment, with minimum inpatient treatment and longterm supervised aftercare, in those localities where no adequate state treatment facilities existed. As late as 1972, the National Institute of Mental Health had found "adequate state facilities" to exist only in New York and California. Persons committed under Titles I and III were assigned to the custody of the Surgeon General to be treated at Lexington or Fort Worth. Persons committed under Title II were in the custody of the Bureau of Prisons which established separate facilities for them.42

Title I of NARA has proved disappointing. U.S. District Attorneys have either been unaware of the Act or reluctant to use it, and the eligible class is so small that few federal defendants qualify anyway. Strict eligibility standards have also inhibited widespread use of Title II, although it has been used to a greater extent than Title I. Title III has served primarily as a mechanism for providing treatment to persons arrested or convicted under state law and then diverted from the state criminal process on the condition that they "voluntarily" commit themselves under Title III of NARA. In this sense, Title III has been a conduit through which federal treatment resources are available to the states and local communities.

Preliminary studies indicate that NARA participants have been somewhat more successful than previous federal patients, at least while they remain in aftercare. The aftercare itself may account in part for this; so might the NIMH screening policy of disqualifying before commencement of treatment, any patient who seems unmotivated. Lexington rejected about one-half of all applicants sent there as "not suitable for treatment." As the inpatient phase of the program has shifted to the communities where the outpatient clinics are located, the rejection rate has dropped, although it still remains relatively high (about 40%) (National Institute of Mental Health, 1971).

In terms of impact, Title IV has been the most important part of the Narcotic Addict Rehabilitation Act. Under that Title, the federal government for the first time provided financial and technical assistance to states and municipalities for the development of drug treatment programs. During the next five years, three other pieces of federal legislation were passed authorizing financial aid to state and local treatment projects.43 By July of 1971, 23 community-based grant mprograms were in operation and 25 additional grants had been made (National Institute of Mental Health, 1971) .

In addition to funding community-based treatment facilities, the federal government has encouraged the adoption of the multi-modality approach. Heavy emphasis is being placed on expansion of methadone maintenance within the multi-modality framework. The National Institute of Mental Health and the Special Action Office for Drug Abuse Prevention, the two federal agencies primarily responsible for community treatment programs, have also urged that patients and programs alike now be judged by more flexible standards. Whereas total abstinence was once the sole criteria of how well a drug-dependent person performed in treatment, "success" is increasingly defined in terms of reduced drug use and improved social functioning.

As was true during the previous heyday of the therapeutic concept of dependence, substantial research activities are now underway searching for new treatment methods. Another important similarity is that research is concentrated now, as then, on finding a drug solution to the drug problem. Today, however, the quest is more sophisticated, and is focused on two specific areas. The first is the development of a much longer-acting form of methadone; it is hoped that this will reduce the patient's dependence on the clinic, and also decrease the risk of diversion of drugs into the illegal market. The second research priority is development of a long-acting opiate antagonist, a drug which itself has no dependence liability but which is capable of blocking the effects of opiate and opiate-like substances. Several antagonists have already been discovered, such as cyclazocine and naloxone, but all are relatively brief in their action, and some produce undesirable side-effects. Researchers are exploring the possibility of a permanent antagonist, a vaccine which would immunize persons against the effects of opiate drugs. Meanwhile, of course, treatment concepts remain ambiguous, and no technique of chemotherapy now in existence by itself can counterbalance the psychological component of drug dependence. For this reason, the contemporary therapeutic approach does not yet promise a solution to the dependence problem. With this qualification in mind, we turn now to an overview of present treatment models.

PRESENT METHODS AND MODELS OF TREATMENT

Models of drug dependence treatment usually combine different treatment methods and techniques. The methods themselves may be described in a series of opposing pairs :

• Drug free, in which treatment begins with withdrawal from de- pendence, or maintenance, in which withdrawal occurs, if at all, only very gradually over the course of treatment.

• Residential, in which the patient remains in the treatment facility, whether a hospital or a therapeutic community, or ambulatory, in which the patient visits the treatment facility at periodic intervals.

• Medical, including chemotherapy and/or psychiatric care, or nonmedical, including group or milieu therapy, as well as social counselling and vocational rehabilitation.

• Selective, in which the program screens prospective patients and accepts only those persons whom it judges likely to benefit, or nonselective, in which the program accepts virtually all patients applying or referred to it.

• Voluntary, in which the patient both initiates and continues treat-

ment by his own choice, or involuntary, in which the patient is

compelled to initiate treatment, or to continue it, or both.

Treatment programs may offer virtually any combination of these methods, even mixing together seemingly opposing elements. Some therapeutic communities, for example, also utilize methadone maintenance, while methadone programs frequently have group therapy and counselling as adjuncts to the medically-based treatment. A halfway house program attempts to combine the advantages of residential treatment with those of ambulatory treatment; patients live in, but are permitted to leave the facility during the day, and perhaps on weekends. Large programs often have involuntary, as well as voluntary patients in treatment.

In the following discussion of the different models of treatment, we will focus on the five most common types : prolonged hospitalization, ambulatory drug-free treatment, therapeutic communities, methadone maintenance and the multi-modality program. In addition, we will examine the still experimental antagonist treatment and treatment for persons dependent on drugs other than opiates.

Hospitalization

Confinement in a hospital for purposes of withdrawal and convalescence is a model of drug treatment dating from the 19th Century. Early methods of rapid withdrawal required inpatient care to deal with the abstinence symptoms. As drug dependence began to appear more intractable, and as methods of withdrawal became more elaborate, special hospitals for drug-dependent patients began to appear. One of the most famous of these was run by the German doctor, Erlenmeyer, and may have provided some psychiatric care in addition to withdrawing the patient (Brill, 1973) .

In its modern form, the hospitalization method consists of three stages. In the first stage, lasting from one to two weeks, the patient is withdrawn from his dependence through steadily decreasing doses of oral methadone. This process involves some discomfort, but little real pain; abstinence symptoms are reportedly reduced to a level of a mild case of the flu.

After withdrawal is complete, the second stage of inpatient psychological care begins. This generally lasts several months, or longer. The care may consist of individual psychiatric counselling, psychotherapy, group therapy,- or work therapy. In addition, this stage aims to prepare the patient to return to the community, giving him time to develop behavior patterns that do not center around drug taking. Some observers also believe that a kind of physical "hunger" for drugs persists even after withdrawal symptoms have disappeared, and that prolonged hospitalization keeps the patient in a drug-free environment while this hunger abates.

The third stage of the hospitalization method is supervised outpatient care in the community where the patient lives. Treatment in this stage may include periodic testing for drug use (urine analysis), psychiatric counselling, group therapy, social counselling or vocational rehabilitation.

Aside from being the most expensive modality, hospitalization has proved to be the least effective method of treatment for drug dependence. In the early days at Lexington, less than 10% of the voluntary entrants remained abstinent for as long as a year after release. The addition of legal controls to keep the patient in the treatment program, and a period of supervised aftercare have improved the rate somewhat. One study indicated that, while only 13% of the patients in aftercare abstained completely from illegal drugs, most used them only occasionally ; and the longer they were in treatment, the less they took (Chatham, et al., n.d.). Of course, this study did not look at those who had left the program during aftercare, so it tends to bias its results toward "success." Moreover, there are no indications that the hospitalized patients perform better in aftercare than those who began treatment as outpatients.

The three largest hospitalization programs are those operated by the federal government (NARA), California and New York.44 Significantly, the National Institute of Mental Health, having already closed the Fort Worth hospital, also plans to close Lexington to patients other than those participating in research, and transfer all treatment functions to the community programs. This, of course, would reduce the inpatient phase of NARA to a formality. Despite this indication of federal disenchantment and the high costs of hospitalization, the method apparently still has its supporters. In 1972, Ohio announced that state mental hospitals will begin receiving drug-dependent patients.

Ambulatory Drug-Free Treatment

Drug-free treatment on an entirely ambulatory basis is a recent innovation. The clinics of 1919-1923 sometimes attempted to withdraw their patients gradually, on an outpatient basis, but these attempts were largely frustrated by the availability of drugs on the illegal market (Terry and Pellens, 1928) . While the illicit market problem still remains, programs are now able to monitor patients through urine analysis, and this appears to inhibit illegal use. In addition, withdrawal can be accomplished relatively painlessly through decreasing doses of methadone.

Ambulatory drug-free programs have essentially the same success patterns as hospitalization and supervised aftercare. During treatment, patients show considerable improvement, greatly reducing drug-taking, involvement with the criminal system, and other undesirable behavior. Like hospitalization with aftercare, though, program self-evaluations are biased toward recording successes; they usually do not count patients who leave treatment altogether, although many of these persons presumably return to dependent status.

Therapeutic Communities

The therapeutic community is a form of residential drug treatment which relies primarily on two complementary techniques of group psychotherapy. The first is confrontation, or encounter-group therapy. Members of the community meet in regular and frequent sessions, in which they analyze each other's past drug-taking behavior and conduct in the program. Through the discussions, the values of the community are announced, inculcated in new members, and reinforced in old ones.

The second technique, a form of milieu therapy, further strengthens internalization of community values. Socially, the community has a hierarchial structure, through which members progress in terms of authority, function, and priviliges as they demonstrate increasing self-discipline and responsibility. Thus, the community rewards and positively reinforces responsible behavior including abstinence, by praise, affection and support in the encounter sessions and by raising the member's peer status. Conversely, the community penalizes and negatively reinforces undesirable behavior, including drug use, with strong criticism in the group meetings and with denial of social advancement (Deitch, 1973).

Community norms themselves emphasize personal maturity and social responsibility. The individual member must learn to control his own behavior and function as a productive member of the group. The older communities usually have an absolute "no drug rule" as well, but more recent programs do not always insist that the member remain completely drug free, as long as his use patterns are not disruptive. Some therapeutic communities now employ methadone maintenance, or allow both maintained and abstinent persons to join (Deitch, 1973) .

Therapeutic communities also vary in how selectively they admit new members and in the length of time they expect members to remain. The original model of the therapeutic community involved rigorous screening of applicants, who had to demonstrate a sincere desire to join the community and to engage in honest self-examination. Many communities still follow this design, but others are not so selective.

With respect to length of treatment, therapeutic communities may be permanent, long term or short term. Synanon, the original therapeutic community is a permanent community; once admitted, members are expected to remain indefinitely. The permanent therapeutic community resembles a religious order; the goal is not reintegration of the member into the secular community, but the development of a special and lasting lifestyle within the communal framework. For obvious reasons, the permanent communities tend to be the most selective in admission and the strictest in internal discipline.

Long-term communities usually require participants to remain in residence for one or two years. At the end of that time, the member is expected to reintegrate himself into society, though he may stay in frequent contact with the community. Lately, short-term communities have developed, with residence requirements of six months or less. These communities operate on the theory that not all patients need isolation from the general community Throughout the treatment period they emphasize member interaction with the society outside. As a rule, their discipline is less strict and they often do not insist upon complete abstinence (Deitch, 1973).

Because it is residential, the therapeutic community is expensive relative to ambulatory methods of treatment. It has the advantages on the other hand, of requiring little in the way of professional talent; many communities, in fact, are operated entirely by the members. Also, some communities, particularly the permanent ones, attempt to become self-sustaining, by developing handicraft industries or having members work at outside jobs.

The dramatic rehabilitation of those drug-dependent persons who complete long-term community residence or remain in the permanent programs has somewhat obscured the fact that the therapeutic community method is suitable for very few. A study of one community in California indicated that two-thirds of the applicants left the program almost immediately, and that at the end of a year only 9% were still in residence; Synanon, too, appears to have had only 10% retention after a year (Deitch, 1973). Even with its rigorous selection process, the therapeutic community is not significantly more effective than other drug-free treatment methods. This would imply the need for stricter selection criteria in the long term or permanent programs. Because the drop-out rate for short-term programs is not nearly as crucial from a cost standpoint, such communities should remain easily accessible to counterbalance the recent emphasis on methadone maintenance.

Another problem with the therapeutic community lies in its origins. Emphasis on self-discipline and vertical mobility, plus the use of the guilt concept in encounter therapy, reflect dramatized versions of middle-class values. With ethnic groups and sub-cultures which do not share these norms, such methods have proved inappropriate. If the therapeutic community is to work for them, it will have to evolve new techniques of group psychodynamics.

Methadone Maintenance

Data show that methadone maintenance is the most significant form of drug treatment currently available. It has proved sufficiently attractive to opiate-dependent persons that even voluntary programs show a substantial patient retention rate, compared with other methods of treatment. Because maintenance programs seem suitable to a wide range of opiate-dependent persons, they are capable of large-scale application. Being entirely ambulatory, they also cost relatively little; the estimated per-patient cost of a methadone maintenance program, for example, is only about $1,000 a year, compared to an average cost of $6,000 a year for hospitalization and aftercare.

During the last few years, methadone maintenance has won a broad spectrum of support, quieting, at least temporarily, the long-ranging feud between law enforcement and medical personnel regarding the proper approach to opiate dependence. Given this widespread acclaim, it should not be surprising that more opiate-dependent persons are enrolled in methadone maintenance (about 70,000) than in any other modality. According to Dr. Jerome Jaffe, Director of the Special Action Office for Drug Abuse Prevention, the number will double by the end of 1973.

Methadone maintenance programs follow one of two models : the high-dose model originally developed by Doctors Dole and Nyswander in New York, or the more recent low-dose model. Both models use oral methadone.'S In the high-dose model, treatment begins by actually increasing the patient's tolerance until it can accommodate a daily dosage of between 50 and 120 milligrams. The advantage of stabilizing the patient at a high-dose level is that the methadone will then completely block the effects of any other opiate drug, like heroin. On the other hand, eventual withdrawal from a high dose regimen is difficult, and the possible dangers of long-term, high dosage treatment are not fully known.

The low-dose model stabilizes the patient on 30 milligrams of methadone a day, or less. At this level, the patient will not experience withdrawal, thereby removing the secondary reinforcement to compulsive drug use. On the other hand, the "blockade" effect of methadone is not complete at low doses. Consequently, the patient's psychological dependence upon the rewarding effects of heroin remains unaffected by the chemotherapy and he can "over-shoot" the methadone with a sufficiently high dose of heroin. In this connection, the low-dose method facilitates the rehabilitation of a patient motivated to change his lifestyle. For other patients, however, maintenance itself will have little impact on the elements which reinforce their drug-using behavior, including the effects of the drug, the ritual of acquiring it, and the experience of intravenous administration.

To counteract these elements, both models of maintenance programs also provide additional treatment, such as group therapy, family counselling, vocational training, and social services. Some studies have indicated those extra services add little in terms of the program's success, although this finding may simply reflect the motivation of the subjects studied or the inadequacy of the rehabilitation services. Many experts have insisted that supplementary treatment is an essential part of maintenance treatment, particularly in dealing with persons who lack skills for legitimate employment (Brown, 1973; Brill, 1973). Under regulations recently issued by the Federal Food and Drug Administration, all methadone programs in this country must now include counselling and other rehabilitative and social services.

During the experimental phase, maintenance programs were fairly selective in admission, seeking older persons, with a relatively long history of dependence, and without any other serious physical or psychological disorders. Older patients usually had a genuine desire to break the heroin cycle as well as a positive disposition toward the non-euphoric, orally administered substitute. Life on the street still has an attraction for most younger patients, however, and they do not do as well on methadone maintenance.

As the programs have expanded and have become an officially preferred alternative to criminal punishment, they have had to broaden their admission policies. The new federal regulations establish minimum criteria for entry. Eligibility is limited to persons who can demonstrate that they are currently opiate dependent and have been so for two years. Persons between the ages of 16 and 18 must obtain parental consent and must have failed at least two previous attempts at drug-free therapy. Those under 16 are ineligible under any circumstances "

In the early, highly selective methadone maintenance programs, the degree of success appeared to be extremely significant. The original Dole-Nyswander program retained 80% of its patients over a five-year period. Of those who left, less than one in 20 returned to regular heroin use, although about 40% of the dropouts had problems with chronic alcohol consumption, and 50% with chronic use of amphetamines, barbiturates or cocaine. Of those who remained in the program, arrest rates allegedly dropped about 97%, while employment rates tripled (Gearing, 1972). A more recent study of programs with less restrictive admission indicate a somewhat lower retention rate (about 65%), and considerably lower rate of employment (Brown, 1973). Reduction in criminal activity, though, allegedly remains very high among patients who remain in treatment.

Despite its relative effectiveness, methadone maintenance has not enjoyed universal support; and its supporters often praise it for the wrong reasons. Both the criticism and praises reflect the fundamental ambivalence now characterizing treatment policy regarding the relationship between abstinence, cure and society's motives for treatment. As to the question of cure, critics claim that methadone maintenance does not really cure the user but merely transfers his or her dependence from one drug to another. With a long tradition of insistence on abstinence, policy makers are a little uncomfortable with the prospect of long-term or indefinite maintenance. For this reason, federal law does specify an ultimate goal of ending patients' drug dependence ; but it prescribes no timetable for withdrawal and no treatment program has yet indicated measurable success in achieving abstinence.

The Commission believes it is time to adopt a realistic concept of drug dependence. Methadone withdrawal whether sooner or later, does not mean the patient is cured, and that he will not use heroin again. On the other hand, maintenance is not inconsistent with cure, if the periodic consumption of methadone reinforces the patient's confidence that he can abstain from heroin, permitting him to function in socially acceptable ways.

In the Commission's view, success, even over the long term, does not necessarily require the removal of physical dependence. The essential component is the removal of psychological dependence. For this, the patient need not be abstinent from all drugs per se, but rather from those which offer the pharmacologic rewards which reinforce compulsive drug-using behavior. The second component of long-term success is replacement of the non-pharmacologic reinforcements for psychological dependence. From this perspective, the goal is restoration of normal social functioning and the redirection of the patient's life away from drug-using and drug-seeking behavior.

Regrettably, evaluation of methadone programs has often been more preoccupied with heroin-free patients than with stabilized patients. While emphasizing the low rate of heroin use, program administrators have frequently overlooked the fact that some patients begin chronic use of other drugs, such as alcohol, amphetamines, cocaine and barbiturates, while in treatment.47 They also ignore the possibility that the reduction in heroin use may sometimes be short-lived.

Research indicates that a substantial percentage of program participants still use heroin, albeit less intensively; and that some patients view methadone programs as a temporary expedient to enable them to reduce their habits to more manageable proportions. These individuals also may exploit the programs to gain legitimate access to other drugs, such as amphetamines and barbiturates. Some programs have dispensed controlled substances other than methadone to deal with ancillary problems reported by patients. This practice may have unwittingly exacerbated patterns of disruptive drug use, including overindulgence in alcohol, thereby aggravating the very problem which the programs are supposed to treat.

This brings us to a second ambiguity of present maintenance policy : society's motives. Supporters urge methadone maintenance as a technique for reducing the urban crime allegedly associated with the need of the opiate-dependent persons to secure money for their drug consumption. By the same token, critics within the Black and Puerto Rican communities have accused policy makers of attempting to establish pharmacologic control over the young minority populations predominant in methadone programs. To the extent that methadone programs fail to make sincere and realistic efforts to integrate their patients into the social and economic mainstream by offering rehabilitative and vocational services, they give credence to such criticisms.

Policy makers must decide whether methadone maintenance is designed to provide symptomatic relief for society or to facilitate the treatment and social reintegration of drug-dependent persons. In the Commission's view only the latter is compatible with the fundamental values of this nation, and criteria for success, over the short and longterms, should reflect this value judgment. The Commision believes that methadone maintenance is a promising means of neutralizing the opiate-dependent person's preoccupation with the drug. Provided drug-free regimens are also available as alternative treatment modalities in every community experiencing a heroin dependence problem, and voluntary entry is emphasized, we believe that treatment officials should continue to expand and improve maintenance services.

Antagonist Treatment

Opiate antagonists are drugs with an anti-opiate effect. They counteract all the effects of opiate drugs in the body. If the person to whom an antagonist is administered has already received a dose of heroin, he will immediately experience all of the symptoms of withdrawal. While the antagonist remains active, subsequent doses of heroin will produce no effect.

Antagonists, then, have the blockade effect of methadone, but none of its potential for physical dependence 48 or euphoria. Some of these drugs, like cyclazocine, cause unpleasant side effects, such as nausea, in early stages of treatment; others become harmful if administration is prolonged. More important, all are relatively short-acting. Cyclazocine seems to be the longest in effect—about 24 hours. Newer drugs, now in the testing stage, may only have a 12-hour duration.

Unless antagonists were to be administered without the patient's consent, which we do not believe is constitutionally permissible, any actual treatment program would be plagued with practical problems. First, participation in such programs would require a high degree of

motivation on the patient's part, as the drug would probably have to be administered twice daily. Since there is no danger of diversion, take-home doses would present no difficulty except for the obvious possibility that the patient would not use the drug. Of course, the treatment facility could call patients in periodically for urine analysis and a clinic-administered dose of antagonist to ensure that they were not relapsing. If a patient had been taking heroin instead of the antagonist, he would probably suffer withdrawal symptoms, a painful recall to the treatment regimen. For awhile, in fact, the civil commitment program in California employed the antagonist. Nalorphine in exactly this manner, a technique whose constitutionality under the Eighth Amendment's prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment is at least questionable.

Alternatively, the program could administer all necessary doses of antagonists to the patient on its premises, but this would create serious administrative burdens. To obviate these problems, researchers are looking for an antagonist that will be effective, in a single dose, for days, weeks or longer. Other scientists are working on a grander project : a vaccine against heroin that could render people immune to its effects for years, if not a lifetime.

Should these research efforts succeed, they will immediately raise serious philosophical and legal questions about mandatory administration. Super-antagonists would not only be vaccinations against opiate dependence, they would also be vaccinations against certain behavioral choices. Admittedly, they would not prevent a person from taking heroin, only from enjoying it. Yet, this distinction merely begs the question, for if society can chemically deprive certain human activities of their perceived rewards, it can effectively prevent the activities themselves. The issues thereby raised extend far beyond the area of drug taking.

Accordingly, the Commission recommends against involuntary administration of antagonists or similar chemical agents, whether as a method of treatment or prevention.

Multi-Modality Programs

Multi-modality programs are those which have combined two or more of the kinds of drug treatment described above. Such programs could include methadone maintenance, detoxification services, inpatient and outpatient drug-free treatment, and a therapeutic community. The Illinois drug abuse program, one of the earliest and most diverse of the multi-modality methods, offers all of these as well as halfway house facilities and opiate antagonist treatment (Brown, 1973) .

Multi-modality programs not only have the advantage of providing patients a variety of treatment methods at the start, but also of being able to move patients easily from one treatment regimen to another whenever appropriate. Patients who do not succeed in one form of treatment have the alternative of entering another. Not surprisingly, multi-modality programs seem to have a higher retention rate than programs with only a single method of treatment (Brown 1973). For these reasons, as well as the importance of individualized treatment plans and alternative drug-based and drug-free methods, the Commission strongly supports the community-based multi-modality approach to drug dependence.

Treatment for Non-Opiate Drug Dependence

No specific treatment program exists for persons dependent on drugs other than opiates or alcohol. Emergency services can deal with acute reactions to amphetamines or hallucinogens and with the abstinence symptoms of barbiturate dependence. There is no drug-based therapy for dependence on any of these drugs, however, and treatment usually consists of individual or group psychotherapy or one of the drug-free regimens used in treating opiate dependence.

Dependence on cocaine and other stimulants may prove even more difficult to deal with than opiate dependence. In the late 19th Century, physicians specializing in care of drug-dependent patients believed that "cocainomania" was a far more intractable and tragic condition than morphine dependence. Similarly, some recent observers have said that the "speed" user is much more difficult to treat than his heroin counterpart.

Swedish public health authorities have reported some success in treating persons dependent on methamphetamines by sending them to sanataria in the country, where therapy is joined with a great deal of outdoor recreation. Some therapeutic communities have also accepted "speed" users, with uncertain results (Canadian Commission, 1972).

THE ROLE OF THE LAW IN TREATMENT

Before passage of the Harrison Act, the government in this country played an ancillary role in the treatment of drug dependent persons. Unless the opiate-dependent person's condition led to an adjudication of mental incompetence, apparently a rare occurence, he generally determined on his own whether or not to seek help. Except for considerations of medical ethics and professional responsibility, choice of therapy was solely between doctor and patient. With a few exceptions, laws neither compelled treatment, nor prescribed one particular method nor proscribed another.

As already pointed out, by 1925, the governmental role had become paramount. The private physician had little interest in the area, and the state and local governments sponsored what little treatment remained. During the next four decades, a majority of states permitted mandatory hospitalization of drug-dependent persons under preexisting commitment laws for the mentally ill or for "inebriates". However, except for the Riverside Hospital program for juveniles in New York City during the 1950's, widespread use of civil commitment procedures for opiate-dependent persons did not occur until California and New York enacted special laws in the early 1960's.

Accompanying the recent upsurge in drug use and an apparent disenchantment with institutionalization as a method of treatment has been an expansion of ambulatory programs and a gradual reinvolvement of the private sector. However, the Government continues, directly or indirectly, to be the financial sponsor of most treatment services, and the primary method of entry continues to be coercieve. The criminal justice diversion approach embodied in the California and New York schemes and in the federal NARA has now been formally or informally adopted in most major jurisdictions.

Federal government control over the availability of psychoactive drugs, along with funding of treatment programs, allows it to determine the kind of treatment opiate-dependent persons receive. The early experimental methadone maintenance programs, for example, required the approval of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics. Even today, the federal government, acting through the Food and Drug Administration, regulates nearly every aspect of methadone's use in maintenance treatment : who may enter the program, what doses may be administered, what other services must be provided. Concurrently, the National Institute of Mental Health and the Special Action Office for Drug Abuse Prevention are actively promoting a nationwide network of multi-modality drug programs, including methadone maintenance, through the medium of federal grants and financial assistance. The Federal Law Enforcement Assistance Administration, with its funds, is encouraging the local police to use the criminal justice system to place opiate-dependent persons into the new facilities.

Society has come to equate drug dependence with serious crime or grave mental illness and, therefore, the extensive government activity in compelling and regulating treatment of this condition does not seem strange. We should recognize, however, that there are few areas of health in which government has intervened so extensively, making detailed decisions for physician and patient alike. One state legislature (California) has even prescribed by statute the exact doses of methadone that may be used during detoxification.

Three broad issues are raised by this extensive governmental involvement in the treatment of opiate dependence. First are the philosophical and constitutional questions raised when the government directly or indirectly coerces a person to be treated, depriving him of liberty in the process. Second are the therapeutic issues relating coercion : whether legal controls on the patient are good or bad erapy. Third are the issues surrounding government intervention the treatment process itself, those raised when certain methods of erapy are forbidden or required. Having addressed the first issue an earlier section of this chapter,49 we now turn to the others.

Legal Controls as Therapy

Almost all therapy involves a measure of control. The patient may

ibe directed to follow a specific diet, to take medicine at stated in- 4ervals, to perform certain exercises, to remain in bed or in a hospital or to refrain from strenuous activity. When a person seeks out professional assistance, there is an understanding, implicit or explicit, ; t1tat he will follow the course of treatment prescribed. The basis

this understanding is the person's desire to get well, and his elief that the physcian can help him achieve this end.

The experience of the federal hospital at Lexington in the 1930's convinced most of its staff, and a number of other observers, that consensual medical controls alone would not work with opiate dependence. Voluntary patients almost invariably left as soon as withdrawal had been completed; just as invariably, they would relapse into drug use and dependence after they returned to their communities. To the Lexington staff, treatment seemed more successful with the federal prisoner patients, who were required by law to remain until released and whose aftercare was supervised by a parole officer. This appeared to demonstrate the necessity of legal control to sup`= plement medical control of drug-dependent patients.

Of course, legal control over drug-dependent persons was established by the state and federal laws criminalizing the incidents of dependence; possession and acquisition. Until the 1960's, however, control was asserted not for treatment but for punishment. In theory, the California, New York and NARA schemes were designed to utilize this legal control for therapeutic purposes, to ensure participation in long-term hospitalization programs. More recently, the criminal offenses have also been used to secure and maintain participation in outpatient programs. Presently, all but four states have procedures which compel drug dependents to enter treatment, or to remain there or both. Many of the procedures refer expressly to dependent persons; others are more general, but are easily adaptable to drug dependent persons. The forms these controls take, and the ways in which they work, are myriad. Most states have formally adopted more than one mechanism and may utilize others informally. The kinds of approaches include:

Civil Procedures

• Patient-initiated, but judicially-ordered, commitment to a treatment program for a period of at least one month and frequently much longer. (10 states)

• Judicial commitment to treatment, initiated by a third person, and resulting in protracted, sometimes indeterminate confinement. (34 states)

• Commitment for purposes of treatment as an adjunct to incompetency, guardianship or conservatorship proceedings. (At least two states specifically provide for this in the case of incapacitated drug dependents.)

• Emergency apprehension and temporary custody, not constituting an arrest, involving transportation of the person to treatment by either a public official or a private individual. (16 states)

Criminal Procedures

• Pre-arrest, formally authorized diversion for purposes of detoxification or withdrawal. (At least eight states specifically so provide.)

• Post-arrest diversion to detoxification. (At least two states specifically so provide.)

• Treatment as a condition of pre-trial release. (One specifically; 27 others authorize conditional release on personal recognizance or to third party custody.)

• Emergency treatment while awaiting trial. (Six states)

• Treatment in lieu of prosecution. (At least 10 and possibly 12 states so authorize.)

• Treatment as a condition of deferred entry of a judgment of guilt and conditional discharge (32 states), or as a condition of suspension of sentence or probation (24 states) .

• Treatment as a condition of parole. (Nine states)

• Commitment for treatment in lieu of other sentence, or while serving a sentence in a correctional facility, or following administrative transfer from a penal institution. (23 states)

The possession laws of every state offer a relatively simple means of compelling treatment. Courts and prosecutors can defer processing of a possession case while the defendant enters treatment and then dismiss the case after he completes it. Alternatively, the judge may offer the convicted possessor a suspended or probationary sentence, providing he enters and remains in treatment. A federally-funded pilot program, known as TASC, or "Treatment Alternatives to Street Crime," encourages exactly this kind of informal, therapeutic diversion. Under this scheme, local police arrest a drug-dependent person for possession, or a like offense. While his case is pending, he must enter a treatment program as a condition of pretrial release. When he comes to trial, the court may consider his cooperation and success in treatment and determine whether he should remain in the program, as an alternative to prosecution or punishment.

As our recommendations relating to the possession offense indicate, the Commission believes that the criminal justice system may properly serve as a mechanism for detecting drug-dependent persons and securing their entry into treatment, so long as basic treatment decisions are made by the medical, rather than by the law enforcement agency and so long as the treatment process is subject to its own network of controls to protect the rights of the patients.

Today, with the development of more effective chemotherapy and psychotherapy in drug treatment, increasing numbers of opiate-dependent persons have discovered that treatment can help them and have entered treatment on their own. The basis for medical control is gradually being restored, and official action should hasten this process in order to reduce the need for legal coercion. At the present time, how-

. ever, legal control over drug-dependent persons is still important in guiding many persons to treatment programs and in retaining formal control long enough to initiate therapy and convince them that participation is in their own interest. Even in this context, emphasis must be placed on maximizing the freedom of choice and action of the patient, limiting overt control to that necessary for effective treatment. The stick should be a subtle one, always in the background, and the carrot should be employed as frequently as possible. In this connection, the Commission reiterates its conclusion that prolonged involuntary treatment should be limited only to the rare cases where the dependent individual presents a clear and immediate danger to the safety of himself or others.

Legal Control of the Treatment Process

In 1963, the President's Advisory Commission on Narcotic and Drug Abuse recommended, among other things :

That Federal regulations be amended to reflect the general principle that the definition of ... legitimate medical treatment of a narcotic addict [is] primarily to be determined by the medical profession (Prettyman, 1963) .

This Commission strongly concurs. Government, state and federal should substantially limit intervention into therapeutic decision-making. In the past, laws have too often restricted drug treatment alternatives, sometimes with disastrous results. Had the federal government not imposed its relatively narrow view of drug treatment on the entire country during the 1920's, it is at least likely that a workable maintenance therapy would have developed much earlier than 1963.

For the most part, current government intervention in drug dependence treatment has a much more healthy influence ; it is directed towards expanding possibilities rather than restricting them. Through its spending powers, the federal government is encouraging and facilitating the development of community-based multi-modality treatment programs, equipped to offer the widest range of known treatment methods and techniques. Official resistance to methadone maintenance programs and ambulatory treatment has virtually disappeared. Indeed, government agencies are now actively promoting both kinds of treatment.

On the other hand, there still remains laws which interfere with effective drug dependence treatment. For example, state law often restricts publicly-funded voluntary treatment programs to opiate-dependent persons. Additionally, most states authorize treatment facilities to refuse admission to otherwise eligible persons on such grounds as excessive criminality or "unsuitability" for treatment. The Federal Narcotic Addict Rehabilitation Act, too, excludes persons "not suitable" for treatment and forecloses diversion of certain federal defendants on the basis of their prior criminal record.

Notwithstanding the restrictive policy of NARA, recent federal funding laws have required federally-assisted programs and facilities to adopt broad admission policies. The Community Mental Health Centers Amendments of 1970 direct community centers receiving federal money to extend services to persons with "drug abuse and drug dependence problems." The Drug Abuse Office and Treatment Act of 1972 further conditions federal assistance to state community mental health programs on developing treatment facilities that provide voluntary and emergency care to all "drug abusers."

The Commission believes that top priority must be placed on making treatment services available to all drug users and drug-dependent persons who apply for assistance. While we recognize that certain kinds of drug treatment, like the residential therapeutic community, may require screening of applicants and restricted entry, criteria which exclude voluntary patients from programs are generally self-defeating. In particular, the Commission feels that such things as prior failure in treatment, or prior criminal conduct should not disqualify a person from receiving treatment. As long as space is available and the applicant is willing to comply with reasonable rules and conditions of treatment, the law should permit, rather than preclude, his admission.

States have sometimes inhibited drug treatment by not respecting the confidentiality of patient information. The most recent state treatment laws commonly insure confidentiality for drug patients, and one state, New Mexico, expressly prohibits police surveillance of voluntary treatment facilities. However, many older laws permit a number of government agencies to have access to drug-patient information. In some states, physicians and facilities treating persons for drug use or dependence are required to report the fact of treatment, together with the patient's name.

Under the 1972 Drug Abuse Office Act, any program receiving Federal assistance or operating under federal authorization must observe certain minimum standards of confidentiality. In particular, patient information cannot be released without the patient's consent, except in limited circumstances. The Commission commends the new federal confidentiality regulations and urges states to adopt similar standards for any programs not covered by federal law.

While the federal government during the last few years has generally taken the lead in removing legal restrictions on drug treatment, it has continued to regulate extensively in the area of methadone maintenance. Because methadone itself has a significant potential for in. ducing dependence, the government has surrounded methadone programs with strictures designed to prevent both diversion of the drug and its administration to persons not severely dependent upon heroin. On the whole, the Commission feels that the present regulations strike a reasonable balance between control of diversion and preservation of flexibility in treatment. The regulations originally proposed by the Food and Drug Administration, however, were considerably stricter with regard to such areas as eligibility requirements and allowance of take-home doses. Had these original recommendations gone into effect, they would have significantly impaired the effectiveness of methadone programs. Even now, requirements that patients visit the clinic at least twice weekly, even after they have been in the program for over two years, may be more restrictive than necessary to accomplish the government's legitimate purpose of preventing diversion.

Government intervention in matters of medical judgment is subject not only to practical objections but also to constitutional ones. In the case of Roe v. Wade,5° decided on January 22, 1973, the Supreme Court held that laws limiting abortions to instances when the mother's life was in danger unconstitutionally interfered with the right of privacy attending health decisions made by the pregnant woman and her physician. The Court's majority stated :