| - |

Drug Abuse

Section XII Research and Information

INTRODUCTION

The primary role of science in the area of the non-medical use of drugs is to provide information to better enable individuals and society to make informed and discriminating decisions regarding the availabilty and use of particular drugs, and the appropriate responses to such use. As we suggested in the Interim Report, scientific research may, in principle, provide useful information and guidance in certain areas, but the scientific method itself is not a policy-making process. Rather it is a practical system designed to explore and test, in abstract fashion, certain kinds of notions or hypotheses. While the aim of scientific research is to maximize objectivity, the interpretation and application of scientific data, as well as the original delineation of the problem or area to be studied, is usually a subjective venture, regardless of the controls maintained in the formal analysis. The practical use of technical data in the personal and social sphere often involves aesthetic, economic, legal, philosophical and moral issues which are not easily amenable to scientific study as we know it today.

In principle, even if there were complete agreement regarding the "scientific facts" of non-medical drug use, the formulation of the appropriate social response at various levels of government would necessarily be based on subjective value judgments regarding the ultimate meaning and implications of the available technical information. It is important to realize the central role of personal concepts of morality and reality in this procedure, and to make explicit the value judgments underlying the interpretation and use of scientific data. At the same time, we must make every effort to assure that this essential subjective evaluation process has the benefit of the most complete and objective scientific and technical information possible.

In the Interim Report, we observed that there was general agreement that society lacked sufficient reliable information to make sound social policy decisions and wise personal chpices in relation to many aspects of non-medical drug use. Not only citizens, but administrative officials, legislators, physicians, scientists and other experts felt that they had an inadequate basis for judgment on this subject. This lack of adequate information at the decision-making level was considered to be the result of problems or gaps in various stages of research, evaluation of existing technical data and information communication. The overall situation has improved substantially since the Interim Report, but much remains to be done to improve this aspect of society's non-coercive response to non-medical drug use.

In recent years considerable attention has been focussed on the role of government in science and on the difficulties in efficiently acquiring, processing, and disseminating scientific information. In the past decade Canada has made considerable progress in developing more coordinated general national and international science policies. A number of major reports on various aspects of Canadian scientific research activities and policies have been published by government and non-government groups, including the Science Council,1 the Senate Special Committee on Science Policy,2 the Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada (AUCC),3 and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).4 In 1971 the Ministry of State for Science and Technology (MOSST) was established and given general responsibility for the formulation and implementation of federal science policy in Canada.5

The Science Council has also published several detailed studies of Canadian scientific and technical information (STI) facilities and needs, and has made specific proposals for the development of federal STI policy.6 The Task Force on Government Information made two relevant reports in 1969,7 and the OECD published a major review of Canadian technical information capabilities and policies in 1971.8 Since then both the Senate Special Committee reports and the AUCC reports cited above have dealt further with these issues. As well, the annual reports of the president of the National Research Council contain significant STI discussion.9 Several background papers on documentation and information in the area of nonmedical drug use were prepared for the Commission," and the basic issues have been discussed in our previous reports. We will not attempt to duplicate here the detailed presentations in the various reports noted above, but will focus on certain drug-related concerns within the framework of the developing federal general science and information policy.

In most respects, the research and technical information needs in the area of non-medical drug use are similar to those in many other scientific fields. It would be inefficient and unrealistic to attempt to create a national drug research or technical information system which was not an integral component of the broader Canadian research and STI networks and programs currently evolving. However, the multi-disciplinary nature of the study of non-medical drug use, certain legal and ethical considerations regarding the substances used, and constitutional issues involving education and health care pose some problems in this area which require special consideration.

In the discussion which follows, the topics of Research, Illicit 'Street Drug' Analysis Facilities, and Scientific and Technical Information are dealt with in primarily separate, but overlapping presentations.

RESEARCH

Until very recently there had been no coordinated general federal effort in non-medical drug use research. Prior to the appointment of the Commission, various related research efforts in universities and other institutions had been supported directly or indirectly by the Federal Government through regular granting channels such as the Medical Research Council (MRC) and, less commonly, the National Research Council (NRC), the Canada Council (CC), National Health and Welfare grants, and National Mental Health grants. In addition, certain relevant research projects had been conducted from time to time in government chemistry laboratories and other federal facilities and agencies. The Federal Government has had little direct involvement in alcohol studies. Although it was possible for government to permit experimental pharmacological research with cannabis and certain other illicit drugs under the federal Narcotic Control Act and Food and Drugs Act, within the framework of the United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961, no such studies were authorized in Canada until 1970. In several instances during the previous decade certain government officials actively discouraged interested scientists from working in this area. Practical roadblocks to such research had existed at both the federal and provincial levels.

In 1946, the former Department of Pensions and National Health published a small booklet entitled Smoking. However, it was another decade before tobacco began to be recognized as a high priority national health problem. In 1963, the first Canadian Conference on Smoking and Health was held, bringing together representatives of federal and provincial governments, volunteer agencies, professional associations, and the tobacco industry. It was recommended by the conference that the Department of National Health and Welfare assume a coordinating and supporting role in a national program of smoking research and health education. Practical implementation of the federal Smoking and Health Program began in 1964. The Program became involved in studies of extent and patterns of tobacco use, related morbidity and mortality data, chemical components of tobacco smoke, and experimental education programs and smoking withdrawal clinics. The Program did not give research grants, but occasionally issued contracts for scientific work in certain areas. The Smoking and Health Program now operates within the Non-Medical Use of Drugs Directorate. Recently a Cancer Research Coordinating Committee was established which involves the active participation of the Medical Research Council, the Department of Health and Welfare, the National Cancer Institute and the Ontario Cancer Treatment and Research Foundation—the four major Canadian sources of funds for cancer-related research. These agencies have provided considerable support for tobacco studies and certain other drug-related investigations.

For a number of years, the Addiction Research Foundation (ARF) of Ontario has been the major Canadian center of scientific activities in the area of non-medical drug use. Although this provincial agency was originally devoted almost exclusively to alcoholism treatment, education and related research, in the past decade the Foundation has become increasingly involved in a wide range of activities pertaining to non-medical drug use in general. In addition to a significant intramural research program, some of which is conducted jointly with the University of Toronto, the Foundation administers a small grant program which provides financial support for research projects in universities and other institutions. Other provinces also support agencies with somewhat similar but generally more limited mandates for various information, education, treatment and research activities. Perhaps most notable are the Narcotic Addiction Foundation (NAF) of British Columbia, and the Office de la prevention de 1' alcoolisme et des autres toxicomanies (OPTAT) in Quebec.

While private industry is primarily interested in the medical use of drugs, much research which is relevant to non-medical drug use is conducted by pharmaceutical companies. For example, they often collect considerable data on toxicology and drug adverse reactions. Although the Commission has obtained a significant amount of research information from certain drug companies, much of their data is not readily available to the scientific community in general.

PERSPECTIVES AND RECOMMENDATIONS OF PREVIOUS COMMISSION REPORTS

As noted earlier, in the Interim Report we indicated that there was a great lack of adequate research in many important areas concerning the non-medical use of drugs.* Until very recently there had been limited scientific investigation of certain illicit drugs, such as cannabis, because of a variety of factors, including the lack of general medical use or previous widespread non-medical use in the Western world, the illegal nature of the drugs involved, and the reluctance of governments to authorize or encourage such research. Many scientists had communicated to the Commission feelings of dissatisfaction and frustration with government research policy in this field. We felt that in some areas, public policy, including research policy, had been influenced more by law enforcement considerations than by scientific concerns.

We recommended that the Federal Government actively encourage, solicit and finance research into the effects, the extent, the causes, and the prevention and treatment of dangerous aspects of non-medical drug use, and that government should ensure an environment of flexibility and freedom for such work. We recommended that the Federal Government make standard samples of drugs, such as cannabis, available to bona fide researchers for scientific purposes. While cooperation with other countries was advised, we recommended that Canada take the initiative to develop an independent research program, including Canadian production of cannabis supplies for experimental research. At the time of the Interim Report a major emphasis was on problems of cannabis research, although the bulk of our discussion was addressed to non-medical drug use research in general.

We recommended the establishment of a national scientific agency to stimulate and coordinate research, and to collect, evaluate, and disseminate the resulting data. We felt that this responsibility could best be carried out by an independent agency, free from political interference, with no connections with responsibility for law enforcement. We contemplated that such an agency might best be independent of government, but should result from careful federal-provincial consultation. While not ruling out a significant contribution by government research personnel, we stressed the importance of involving independent scientists in universities and other institutions in the overall research effort. We emphasized that government policy and action in this area should be explicit, and the basis for government decisions made public. In the Treatment Report and the Cannabis Report we dealt with certain general scientific issues and made a number of specific suggestions as to directions and priorities for future research, but did not provide significant further commentary on the Federal Government's regulatory and financial activities and responsibilities in this area.

THE NON-MEDICAL USE OF DRUGS DIRECTORATE AND RELATED FEDERAL PROGRAMS: AN OVERVIEW

In January 1971 the Department of National Health and Welfare inaugurated a non-medical use of drugs program as a separate division of the Health Protection Branch (HPB). The program was designed to coordinate the federal effort in research, information, treatment and prevention of problems associated with non-medical drug use. Since its initiation the program has undergone numerous changes in organizational structure and senior administrative personnel. In the fall of 1971, it was temporarily reorganized as a separate directorate of the Department of Health and Welfare, but in 1972 it was altered again, and the director of the Non-Medical Use of Drugs Directorate (NMUD) now reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister in charge of the Health Protection Branch. A committee of experts was appointed from various disciplines, representing government and non-government sectors, to act principally as an advisory group to NMUD with respect to goals, priorities and policy, and to review research grant applications. The Directorate's internal structure is currently undergoing reorganization. New evolving bureaux are functioning at differing levels of activity and completeness. Most of their programs are still in the early stages of development.

The NMUD research program was initiated as a combined effort of the Health Branch and the Welfare Branch of the Department of National Health and Welfare, with the Medical Research Council. The program presently administers its own research budget and is no longer dependent on external support from National Health and Welfare grants; contributions to research funds from these sources were transferred directly to the program in 197273. The research program, which is basically extra-mural, has remained a joint endeavour with the Medical Research Council. The granting procedure is based primarily on the MRC model and general mode of operations. As noted above, applications are reviewed and decisions are made by expert committees assisted by outside consultants, many of whom are peers of the applicants in the scientific community. In addition to providing financial support through grants and contracts, the Directorate arranges federal authorization when needed and standard drug samples for animal, human and chemical research. Supplies of certain restricted drugs have been made available from the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health.

The Directorate has initiated a program to provide information and educational materials to the public and various special groups. As well, a scientific and technical information service for NMUD personnel and other researchers is being developed. Support for innovative service projects has accounted for a major part of the non-operating expenditures of the directorate. The activities of the Federal Government in this area are discussed in detail in Appendix M Innovative Services. The Smoking and Health Program, formerly under the Health Services Branch, was taken into NMUD in 1972 relatively unchanged, but with an increased budget.

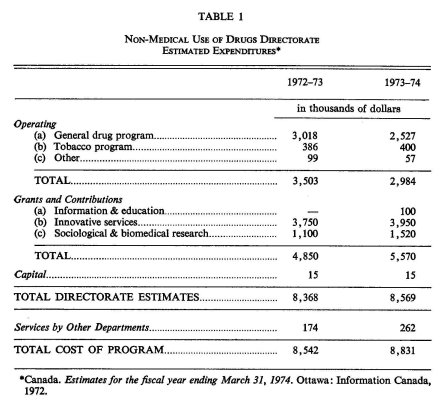

In the first full fiscal year of its existence (1971-72) the non-medical drug use program operated on a budget of approximately $4 million, most of which was accounted for by operating expenses. The estimated total expenditures (including services, contributions and grant funds channelled from other sources) for 1972-73 and 1973-74 were approximately $8.5 and $8.8 million, respectively. Table 1 provides a more detailed breakdown of these estimates.

For the last three years NMUD has provided summer research scholarships for graduate and undergraduate students working with established scientists. In the past, there were some problems coordinating the allocation of these student scholarships with general research funds and drug supplies for laboratory studies, but the program has improved considerably and appears to be making a valuable contribution to research and training in this area. For summer 1973, $315,000 were allocated for 180 such scholarships.

There are other sections of the Health Protection Branch (HPB) which also deal with various aspects of non-medical drug use. The Drugs Unit of HPB has three bureaux: the Drug Advisory Bureau, the Bureau of Dangerous Drugs, and the Drug Research Laboratories. The Drug Advisory Bureau administers the Poison Control and Drug Adverse Reaction Programs, maintains supplies of drugs for distribution for research or analytic purposes, and is responsible for maintaining standards of quality control in the pharmaceutical area. The role of the Drug Advisory Bureau in controlling the medical use of methadone is discussed in detail in Appendix G.1 Methadone Control Program of the Government of Canada. The Bureau of Dangerous Drugs (BDD) monitors drug importation, manufacture, distribution and, in some instances, prescriptions and medical use. BDD is also involved in other aspects of the enforcement of federal drug laws, and keeps national records of certain illicit drug users and offenders. The regional laboratories of the HPB Field Operations Directorate, along with the Drug Research Laboratories in Ottawa, provide most of the federal forensic drug identification, and are also involved in certain intra-mural research projects.

Various other departments and agencies of the Federal Government, such as the Departments of the Solicitor General, Manpower and Immigration, and Secretary of State, and the National Research Council Laboratories have been involved from time to time in research projects relevant to the non-medical use of drugs. Most such studies are of a statistics-gathering nature or involve evaluation or monitoring of some of the agency's activities. Data from many of these projects are discussed in the appendices to this report. In 1970-72 the Department of Agriculture and the Department of National Health and Welfare conducted a joint botanical research program in Ottawa which, in addition to exploring certain genetic aspects of cannabis, provided a standard Canadian supply of marijuana for research purposes.

GENERAL OBSERVATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

In the first year of the NMUD research grant program numerous scientists communicated to the Commission that they were frustrated with various aspects of the Directorate's services. The problems generally centered around unexpected and unexplained delays in decision-making, subsequent feedback, and the delivery of grant funds and experimental drug supplies after committee approval. The major administrative difficulties underlying these problems have apparently been resolved, but recent communication with Canadian scientists indicates that some dissatisfaction still exists, even though there has been substantial improvement in these services. Further effort will be needed to make the decision-making process more efficient and to improve the quality of the feedback provided to both successful and unsuccessful applicants. We feel that special effort should be made to communicate detailed critical and constructive comments to unsuccessful applicants to guide them in preparation of future proposals. New researchers in the area must be encouraged and assisted in learning the essentials of "grantsmanship" within the context of this program. Additional effort should be made to operationalize, quantify and communicate the specific criteria and decision-making processes employed in distributing research funds.

In principle, the NMUD research committee must deal with applications requesting one or more of the following: (1) authorization to possess narcotic or restricted drugs for research or analytic purposes; (2) standard supplies of such materials or a licence to obtain them independently; (3) financial support for specific research projects. There has been some controversy regarding the appropriate criteria to be employed in the various situations which arise, and the legal obligations and limits of jurisdiction of the Federal Government in this regard. Researchers or analysts must obtain federal authorization for work with narcotic or restricted drugs, and such scientists typically also request supplies of the drugs and often financial support as well, but this is not necessarily the case. For example, a researcher may work under nonfederal or independent support and might have other legitimate sources of the drugs in question.

Because of competition among scientists for obviously limited funds, highly selective procedures must be employed in allocating financial support, with the primary criteria essentially being: (1) the relevance of the topic with regard to research priorities; and (2) the scientific excellence of the specific proposal and researchers involved. Assuming that ethical requirements have been met, these dimensions are assessed by the research committee and its external referees—principally the applicant's peers in the scientific community.

Similarly, if a researcher has requested drugs which are in limited supply, a highly selective process would be indicated, as with grant applications. However, if financial support is not involved, and only authorization is requested, or authorization and drugs in common supply, then a much simpler procedure is generally appropriate. In such situations, the obligations and powers of government, within the framework of the Narcotic Control Act and the Food and Drugs Act and related regulations, are rightly limited to establishing: (1) that the request involves a bona fide scientific effort; (2) that appropriate drug records are kept and precautions are taken to prevent diversion to illicit use; and (3) that the drugs are employed in a safe and ethical manner. With the present protocol, the responsibility for ensuring that the ethical requirements are met has been delegated to independent ethics committees—typically within the university or other institution involved. Approval from such a group is required before an application is considered by the NMUD research committee. Conditions of drug records and storage are subject to assessment by Health Protection Branch officials. Establishing that the drugs are to be used scientifically would rightly seem to be the duty of the research committee of peers appointed by the Federal Government, as is now the case.

The Commission feels that the Government need not declare itself on the merit of a particular research project if only a supply of drugs and/or research authorization is requested. Such applications should be routinely approved unless there is serious doubt about the credentials and qualifications of the scientist involved. We appreciate that there may be reasonable concern as to the likely value of certain research efforts, and that the temptation is strong to try to dictate quality at the bureaucratic level. But we feel that, in the long run, a substantial degree of flexibility and freedom for the individual researcher, within reasonable ethical and financial limits, is essential for the proper atmosphere for scientific advancement. In any event, the long-term output or quality of a researcher's work is generally under considerable assessment and control through various other processes within the institution or local community in which he works and need not be the direct responsibility of the Federal Government.

At the present time, authorization to conduct research with narcotic or restricted drugs is in some respects tied too closely to specific projects. Given the necessary and continual evolution of research strategy and techniques, the government should ensure that the regulations do not place undue restriction on the flexibility necessary for the timely and effective pursuit of scientific goals. We feel that some form of general licensing of qualified scientists, rather than specific project authorization, may be more appropriate and efficient in the long run.

Determining scientific research priorities, keeping them flexible and timely, and communicating them effectively to the appropriate researchers is a very difficult task. Priority lists, especially in the area of non-medical drug use, rapidly become out-of-date unless subject to continual review and re-evaluation. If priorities are presented too dogmatically there is a very real danger of precipitating a 'bandwagon' effect at the top of the list, which may drastically reduce efforts which might in the long run have fruitfully gone into other important topics. It is necessary that the Federal Government determine and communicate the general and specific areas of research which it feels are most in need of attention and are most likely to receive financial support—both immediate and long-term. It is also essential that there is reasonable flexibility in the granting system, and that procedures are developed which can provide rapid bureaucratic decisions and funds for work involving important emerging ideas, new approaches, `crisis' situations, and transient and unique opportunites for scientific inquiry which might otherwise not be effectively supported. It is important to appreciate differences in priorities at the national, provincial and local levels. While the major problems of non-medical drug use are clearly of national concern, local conditions or crisis situations may vary considerably among geographic areas. The Federal Government should increase its capacity to share the costs of provincially directed, problem-oriented research.

In the first two years of its research program NMUD predominantly supported cannabis studies in the biochemical, physiological and psychopharmacological areas. Relatively little work has been initiated or supported in the social-behavioural fields. NMUD has changed its early emphasis on biomedical cannabis research and is expanding the breadth of the coordinated program.

NMUD should continue to stress grants to scientists in universities and other institutions which are relatively independent of government. However, it should include specific contract projects and also research by government scientists in special situations which could not be efficiently handled through the grant program. In certain circumstances, the Directorate should provide or contribute to salaries on a contract or grant basis for reseachers not working under traditional institutional auspices. (Note that the MRC grant program presently does not cover principal researcher salaries.) In most instances (e.g., universities and drug research foundations) senior researcher salaries come primarily from provincial sources.

Many aspects of non-medical drug use research are relatively new to the Canadian scientific community. Although the nation's research capabilities in this general field are expanding, significant areas exist where there are serious deficiencies in available scientific personnel—either because of an absence of researcher interest or a lack of appropriately trained or experienced investigators. This situation, of course, has significant bearing on the success and growth of the NMUD national research program. Considering the present stage of development of the NMUD program, the Directorate's overall budget for 1973-74 (see Table 1 on page 187) may be adequate. However, as the capabilities and interests of the Canadian scientific community expand in this area, and as the NMUD program becomes more complete in its coverage of drugs and research topics, a significant increase in funds will be necessary.

Compared to other research disciplines, the social sciences have traditionally been weak in Canada. Until recently there were few, if any, adequate facilities for advanced training in sociology and anthopology in this country. As a result, most Canadian social behaviour researchers have taken the bulk of their graduate studies in other countries—primarily in the United States or England. Similar situations exist in other specialized areas relevant to the study of the non-medical use of drugs, such as psycho-pharmacology. The Federal Government should work with the provinces to generally strengthen relevant social science programs in Canada, and should initiate through NMUD a limited program of pre-doctoral and postdoctoral fellowships in various scientific disciplines specifically for advanced training in research in the area of the non-medical use of drugs.

There is a general need for a coherent macroscopic approach to research in the field of non-medical drug use. There are significant questions requiring intensive investigation in relatively restricted and well-defined areas, but cooperative multi-disciplinary studies involving input from experts in various fields will be necessary for effective advancement of scientific knowledge of many important general topics. The Federal Government should encourage multi-disciplinary research efforts, and generally act as a catalyst to arrange or facilitate communication and cooperative studies among scientists working in related areas. While some degree of geographic centralization is preferable for such team efforts, it is not always essential if adequate communication channels exist. The Federal Government should work with the provincial governments to strengthen existing multi-disciplinary research groups or to develop new ones within appropriate universities, provincial drug treatment and research foundations, hospitals, and correctional or other institutions. Such efforts should include necessary financial support. A loosely coordinated, decentralized network of research groups across the country would seem preferable to a single national research institute located in one city such as Ottawa or Toronto, for example.

International conventions and controls regarding psychotropic drugs are discussed in Sections VI and VII of this report. Unlike the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961, which did not attempt to regulate conditions for scientific study, the Convention on Psychotropic Substances, 1971, presents special provisions for controlling research with certain drugs. Article 7 of the Convention requires strict controls on the manufacture, distribution, possession and record keeping of hallucinogens (including THC) for research purposes. Furthermore, parties to the Convention are required to "prohibit all use" of such substances "except for scientific and very limited medical purposes by duly authorized persons, in medical or scientific establishments which are directly under the control of their governments or specifically approved by them." No attempt is made in the Convention to define the word "establishment", or to specify the nature of the governmental "approval" to be required for non-government research bodies. We feel that this clause should not be interpreted so as to exclude research by bona fide scientists working alone or in private or independent laboratories. If such interpretation is considered to be unavoidable Canada should not become a party to the Convention without suitable amendment or reservation on this point. In our opinion the present Canadian provisions and protocol for authorization of research with narcotic or restricted drugs, as described above, satisfy the specific approval requirement of the Convention. The Convention provides for special licensing of researchers and approved establishments, and does not necessarily require separate specific approval for individual studies or projects by authorized scientists. The present Canadian system of control and regulation of drug storage and record-keeping by researchers is consistent with the Convention, and seems adequate to prevent diversion to an illicit market. With the above reservation, we feel that Canada can provide an adequate atmosphere for scientific inquiry within the framework of the Convention.

Many general and specific suggestions for research are made in the context of the discussions and reviews presented in other sections and, in particular, in the appendices to this report. In addition, our previous reports contain research recommendations. A separate section in the Cannabis Report was devoted to important topics and priorities for scientific study; that discussion is still appropriate in spite of significant recent advances in certain areas. The general issues dealt with there have relevance to research involving other drugs as well, and should be considered in that broader context.

ILLICIT 'STREET DRUG' ANALYSIS FACILITIES

Systematic analysis of 'street drugs' for non-forensic purposes was first undertaken in Canada at the Addiction Research Foundation (ARF) in 1969. Technical assistance and reference samples were provided to the Foundation by the Federal Food and Drug Directorate (now Health Protection Branch [HPB]). From time to time various other laboratories across the country were involved in 'street drug' analysis on a more limited and less systematic basis. The legal position of the analysts and of persons presenting the illicit drug samples for analysis was ambiguous, but a number of laboratories operated on the premise that such work was justified under provincial health statutes. As a result of local pressure from law enforcement officials, in early 1970 the ARF collection and analysis of illicit 'street drug' samples was temporarily suspended, pending legal clarification. Some critics felt that the services provided by the Foundation in this project facilitated the refinement of certain illicit drug manufacturing and trafficking activities- in other words, they were concerned that such analyses and subsequent feedback would provide a source of quality assessment for the illicit market. The foundation, on the other hand, contended that the laboratory project had not become a service to the 'black market', but was a significant aid to medical treatment, a valuable source of epidemiological data for research and educational purposes, and a potentially important independent source of information input to the criminal-justice system.

In our Interim Report discussion of 'street drug' analysis, we observed: It is feared by some that such facilities and information may encourage the use of drugs by advertising their availability and reducing dangers. It has been further suggested that distributors will take advantage of these facilities to have their products tested and, as it were, approved. Whatever force there may be in these arguments, they are outweighed, it would seem, by the necessity of a thorough and effective commitment to know as much as possible about what is happening in non-medical drug use and to make such knowledge available for the benefit of those who may be prudent enough to be guided by it. We have more to fear from willful ignorance than we do from knowledge in this field .... Sample analysis and wide dissemination of the results can only serve in the long run to deglamourize drugs and drug taking. [P. 228.]

In the Interim Report, the Commission pointed out that the existing facilities could not meet national requirements for the analysis of illicit market drugs in non-medical use. The FDD and RCMP laboratory facilities were not considered timely or appropriate sources of information for persons involved in medical treatment and research. The ARF laboratory project had been suspended; at any rate it had been a significant service primarily to those in Southern Ontario only. At the time we recommended:

... that the Federal Government actively investigate the establishment of regional drug analytic laboratories at strategic points across the country .... Such laboratories should not be connected with government or law enforcement, and should be free from day to day interference by public authorities. [P. 228.]

In November 1970, amendments to the Food and Drugs Act and the Narcotic Control Act were passed which clarified the legal position of those involved in such laboratory operations, and provided a protocol for federal approval and authorization. Under these regulations, physicians were permitted to receive samples of narcotic, controlled, and restricted drugs from individuals under their professional care, and to transmit such samples to a scientist authorized to conduct the analysis. Feedback from the analyst regarding the contents of illicit samples was restricted to the physician. In 1971 and 1972, certain aspects of the regulations were further altered, and, currently, physicians can receive drug samples for analysis from persons other than their patients. Applications for authorization to conduct analyses were considered from university, hospital, government, and private laboratories.

However, until recently, the Federal Government did not provide direct financial support for analytic projects outside of the Department of National Health and Welfare, since it was felt that such activities fell within the area of the delivery of health services and, consequently, would be more appropriately developed through provincial auspices and support. In the summer of 1971, the Food and Drug Directorate conducted workshops on illicit drug analysis designed to provide chemists from across the country with up-to-date information on standard techniques for the quantitative and qualitative analysis of drugs likely to be encountered on the street. A technical manual entitled "Some analytical methods for drugs subject to abuse" was produced and distributed.11 Since 1972 the Federal Government has provided financial support for a few research-oriented, non-government 'street drug' projects through the NMUD analytical services program.

In 1971-72, the Commission surveyed all authorized laboratories, requesting information on the alleged and identified contents of samples received, general analytic methods employed, sources of funding, and relations with local law enforcement, medical and Federal Government authorities. * Today the bulk of the non-forensic analysis of illicit drugs in Canada takes place at the Addiction Research Foundation in Toronto, although many other laboratories across the country are involved from time to time in such work.

By early 1973, over 100 individuals in more than 50 different laboratories had received authorization to conduct analyses of illicit drugs. However, relatively few are seriously involved in 'street drug' work, and less than half a dozen have a program of notable magnitude. Although they are fully authorized, technically qualified, and generally adequately equipped, most of the laboratories are not actively involved in 'street drug' analysis for a variety of reasons. Lack of adequate financial support has been a considerable stumbling block and, as a result, some labs either charge for the service (as much as $40.00 per sample) or have abandoned illicit drug work altogether. Those laboratories with somewhat successful programs have generally had to incorporate their costs into existing hospital, research or university budgets. In many locations, the anticipated street drug workload has not materialized, either because of an absence of local interest or need, or because of a lack of information and knowledge of such facilities by treatment personnel, illicit drug users and the general public.

In order to obtain more complete information on the composition of illicit drugs at the street level, the Federal Government expanded the facilities of the Health Protection Branch laboratory in Ottawa and the five regional laboratories. In 1971, the HPB initiated a special police drug seizure analysis program concerned with exploring the strength and purity of illicit drugs. In addition, the HPB has continued on a relatively small scale to analyse `street drugs' for physicians "on an emergency basis".

OVERVIEW OF ISSUES AND RECOMMENDATIONS

As discussed in detail elsewhere,* in order for controlled laboratory research to have practical social relevance it is necessary to maintain accurate information regarding the identity, purity and potency of the drugs being consumed from illicit sources. Furthermore, such knowledge is necessary for adequate public health protection and treatment, and is essential to meaningful administrative control and regulation. The potential importance of drug analytic services to physicians in aiding them in the diagnosis and treatment of drug-related problems has been widely discussed.

There is still some disagreement as to the most practical system for obtaining the necessary information about illicit drugs. As suggested in the Cannabis Report,f it is our belief that up-to-date systematic selection and analysis of police seizure samples, supplemented by information from a few medically oriented and other 'street drug' analysis programs in the primary urban centres, could provide an adequate basis for monitoring the general, picture as to the drugs available on the illicit market. The special HPB study of police exhibits represents a significant step in this direction, but more systematic sampling is necessary.$

The effective use of 'street drug' analysis in the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic drug effects poses somewhat different problems. It is frequently said that rapid 'street drug' analysis would be of considerable value to the treatment of adverse reactions. However, our studies suggest that immediate drug identification would typically not be as significant a contribution to the management of psychological adverse reactions as is often contended, since drug-specific treatment is generally not available in any event. The handling of such cases is usually based on the interpretation of behavioural symptoms, and most commonly involves 'talking down' and, often, the administration of minor tranquilizers, regardless of the original drugs involved. § In cases of severe physical poisoning, rapid identification of the chemicals taken would be invaluable, but traditional drug analysis methods are usually unable to provide the necessary information quickly enough to be of effective use, even in the uncommon event that adequate samples of the drugs taken are immediately available. Currently, emergency poisoning or overdose treatment is primarily based on observable symptoms and verbal reports by the patient or his friends as to the chemicals involved. Immunoassay of drug, blood or urine samples might require only minutes for drug identification, and would be extremely useful in many such emergencies, but very few treatment facilities in North America are presently equipped for such methods. * In treating the effects of chronic drug use, chemical identification of the substances taken is generally not of paramount importance, since, again, drug-specific treatment is generally not provided or available—particular physical disorders and symptoms, and behavioural conditions are treated instead. As discussed in detail in Appendix A The Drugs and Their Effects, even though there is considerable misrepresentation, confusion and fraud within the illicit drug market, the deliberate mixture or adulteration of single drugs with other chemicals- or the substitution of more dangerous chemicals for an alleged drug is relatively rare in Canada. Drug users are presently more likely to be cheated than injured by the information gap regarding the identity of illicit drugs.

It would appear that the apparent 'street drug' analysis crisis of a few years ago is not now as important an issue as it was at the time of the Interim Report. However, some further attention is warranted: We make the following recommendations:

(1) The Federal Government should continue, but refine, the present HPB special studies of police drug exhibits.

(2) The Federal Government should continue to provide authorization, standard methods, and standard chemical samples for illicit drug analysis to bona fide scientists.

(3) The Federal Government should continue to provide funds for a few key `street drug' analysis research projects in the main urban centres across the country. As suggested in the Interim Report, the financing of such facilities could well be a matter of federal-provincial cooperation.

(4) The Federal Government should encourage the correlation of chemical characteristics of the samples with the medical, social and legal conditions leading to the analysis. In this context, the Federal Government should explore the feasibility of coordinating drug identification with certain aspects of the present Poison Control Program of the HPB.

(5) The Federal Government should encourage uniform central reporting and dissemination of the results of drug analyses, and should make the data from the HPB police seizure studies rapidly available to researchers for analysis and publication.

SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNICAL INFORMATION

Prior to the appointment of the Commission, a small information program was conducted by the former Drug Abuse Secretariat of the Department of National Health and Welfare. The federal Smoking and Health Program has been providing tobacco information, films and various teaching aids on a national scale for almost a decade, but almost no federal effort has been invested in alcohol information. Numerous provincial groups, most notably the Addiction Research Foundation of Ontario (ARF), but also the Office de la prevention de l'alcoolisme et des autres toxicomanies (OPTAT) of Quebec, and the Narcotic Addiction Foundation (NAF) of British Columbia have developed significant information and educational materials dealing with a wide range of drugs. In the past few years certain private groups, such as the Council on Drug Abuse (CODA), have also entered the field. ARF has for years been the primary Canadian source of scientific information in this area, and has regularly supplied such materials to individuals and organizations in all provinces and in numerous foreign countries. There has been little specific effort to coordinate the various drug information resources available in Canada.

PERSPECTIVES AND RECOMMENDATIONS OF PREVIOUS COMMISSION REPORTS

In the Interim Report we observed that there was an urgent need for some coordinated system on a national scale to collect, classify, index, evaluate and disseminate timely information on various aspects of nonmedical drug use. * We stressed that there must be some efficient source of disinterested and authoritative opinion, independent of political pressures and responsibilities for law enforcement, to which those seeking information could turn for guidance for public policy, education, medical, scientific and personal decisions. We recommended that the creation of an appropriate national information program be given high priority. We acknowledged the important role of the news media in this area and recommended that the Federal Government keep the media as fully informed as possible of its own information about non-medical drug use. (See also Section XIV The Mass Media in this report.)

In the Treatment Report we noted the need for factual information and educational material for use and dissemination by community treatment services. f In addition to scientific and technical data, reliable information is needed regarding existing agencies which deal with various specific problems, including medical, legal, educational, and occupational situations. We suggested in the Cannabis Report that a centrally coordinated documentation, information-gathering and alerting network would greatly facilitate effective communication among researchers4 Because of the accelerating growth of scientific information on non-medical drug use, traditional modes of publication, communication and information retrieval have become increasingly inadequate. We suggested that international cooperation and coordination in this area might be effectively conducted through the World Health Organization.

In the Interim Report we observed that the development, collection and evaluation of technical information was one thing and the effective dissemination of processed information to the public for educational purposes another. These two functions typically involve different skills and expertise and, consequently, might best be carried out by different individuals or agencies. We felt that the national scientific agency which we recommended to conduct the Federal Government's coordinating and financial initiative in research should also be responsible for the collection, evaluation and communication of the resulting technical data. We discussed a number of mechanisms by which this information might subsequently be used in drug education or otherwise effectively disseminated to the public. We noted evidence that many young people lacked confidence in certain official sources of drug information, and that to be accepted such information might best be disseminated by local groups or individuals having high credibility with youth. We also discussed the Canadian Medical Association's suggestion for the formation of a coordinated network of regional non-governmental multidisciplinary groups or "teams" to provide information, policy guidance and other services at the community level.

The division between the collection, evaluation and distribution of scientific and technical information, on the one hand, and the actual preparation of educational materials and the process of education, on the other, is admittedly sometimes ambiguous and necessarily arbitrary. Because of constitutional provision for provincial responsibility in the area of education, the distinction between drug information and drug education is of considerable significance in determining the appropriate role for the Federal Government in this area.

We noted in the Interim Report that:

In the Commission's view, the notion of drug education implies more than a mere random conveying of information; it implies selection, system, purpose and perspective. [P. 229.]

The objective of the information system is to provide timely scientific data in usable form as objectively as possible. The goal of the educational process is to present these data and other relevant information in a manner which prepares or enables individuals to make informed and wise personal choices. The provision of evaluated technical information is clearly within the federal sphere. Further, as we suggest in Appendix F.1 The Constitutional Framework, provincial responsibility for formal education in the school system does not preclude an important federal role in communications of general educational value and in collaboration on the development of drug educational materials and techniques. As noted in the Interim Report, we feel that there should be a federal-provincial body for the development of drug education materials and methods, making use of information collected and evaluated at the national level. There are further observations on drug education in Section XIII of this report.

THE RANGE OF INFORMATION SERVICES NEEDED

An ideal national information network would be capable of providing various services to a wide range of users: scientists; medical and other treatment and rehabilitation personnel; legislators and government administrators; educators, teachers and students in various levels of school and university; industry; other private organizations; news media reporters; justice and law enforcement personnel; the clergy; librarians; and other citizens, including drug users of all ages. The potential users of such information can be considered in three groups with somewhat different, but overlapping, needs: (1) researchers and other scientific or technical experts; (2) persons who are not technical experts, but who deal in their work with certain aspects of nonmedical drug use; and (3) the lay public.

It is clear that scientists must be aware of, and have efficient access to, the existing scientific literature and relevant data, and must be informed as to new developments, ongoing and anticipated research, and scientific meetings. The second group is more likely to need secondarily prepared materials such as selected bibliographies and book lists, critical summaries and reviews, text books and other evaluated or predigested information. The third group, the lay public, is most likely to receive information indirectly through individuals in the second category. A wide variety of intermediate sources involving further information processing and selection would undoubtedly be involved, including news media, formal drug education programs, and so on.

THE NON-MEDICAL USE OF DRUGS DIRECTORATE INFORMATION PROGRAM

As part of its overall information effort, in the fall of 1972 the Non-Medical Use of Drugs Directorate (NMUD) began work with the Health Protection Branch Library on a coordinated scientific and technical information network and data base in Ottawa. A computerized system was designed to provide specialized bibliographic searches of the scientific literature, and altering and up-dating services. Considerable progress was made towards creating the basic data bank, but many problems and issues remain to be resolved. The National Science Library services (e.g., Canadian Selective Dissemination of Information [CAN/SDI]) are presently available to the NMUD system. Direct on-line connections with the U.S. National Clearinghouse for Drug Abuse Information (NCDAI), Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval Systems (MEDLARS) and other American services have been established. The immediate goal of the data base was to serve the needs of NMUD personnel, although certain services for researchers and other groups were also intended and are currently being explored.

Plans were made at NMUD for data evaluation and further processing of scientific information for possible use in fact sheets, review articles, text books, audio-visual presentations, etc. In addition to the existing government communication agencies, such as the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, the National Film Board and Information Canada, new federal and provincial information channels are being considered for dissemination of this information. NMUD has distributed special bibliographies and other information to certain research, treatment, and education groups, and has held a number of national conferences and meetings designed to stimulate and facilitate communication among workers in various areas. However, little substantial progress has been made in many aspects of the anticipated information programs, and in certain respects the NMUD system is still in the early stages of planning and development.

THE ROLE OF EXISTING INFORMATION RESOURCES

A considerable number of specialized drug information resources already exist in Canada and other countries. It would not be advisable to attempt to duplicate these collections in a central data bank anywhere. Instead, the Federal Government should emphasize the development of a coordinated network of complementary information resources in Canada, establish open two-way communication with information centres in other countries, and proceed to identify and fill gaps in the collective system on a multi-lateral basis. Research and information in this area clearly transcend traditional provincial and national boundaries, and a major cooperative effort must be made involving various levels of government. We need to improve our ability to absorb and use information from foreign sources, and should avoid undue duplication of resources available to us from other countries. Additional funds must be made available for the rapid translation of important foreign language articles into one or both of the official languages. A standard but flexible multi-lingual international thesaurus of key retrieval index terms dealing with non-medical drug use is clearly needed.

The major relevant information collections and services now existing in Canada include: the National Library, the National Science Library and certain federal departmental libraries and their information systems (e.g., CAN/ SDI); the Addiction Research Foundation (ARF), Office de la Prevention de l'Alcoolisme et des autres Toxicomanies (OPTAT) and certain other provincial agencies; university libraries (e.g., Laval); the Commission library; and the NMUD data base currently being developed. Primary foreign resources include the various U.S. National Institute of Health clearinghouses (e.g., NCDAI), the U.S. National Library of Medicine (e.g., MEDLARS), the U.S. Library of Congress, the Student Association for the Study of Hallucinogens (STASH), the Rutgers Alcohol Centre (e.g., CAAAL), the Smithsonian Institution, the Fitz Ludlow Memorial Library, the various United Nations divisions and libraries, the Institute for the Study of Drug Dependence in London, the Automated Subject Citation Alert (ASCA), Excerpta Medica, and the various sociological, psychological, biological and chemical abstracts. The major pharmaceutical companies in various countries have significant specialized information collections as well

The Federal Government should maintain an up-to-date inventory (e.g., indexed lists of project titles, researchers and abstracts) on current drug research in Canada and other countries. Considerable progress in identifying and listing Canadian scientific efforts has been made by the National Research Council through the National Science Library's Information Exchange Center (IEC). Further efforts should be made to include provincially and privately funded and conducted research as well as university projects financed through federal sources. The Ministry of State for Science and Technology (MOSST) is extending the present coverage through the phased establishment of an Inventory of Scientific Activities, incorporating the functions of the IEC. Descriptions of publicly funded research projects should be routinely published and made available to the public.

A comprehensive catalogue of the total holdings in the various Canadian drug information collections must be established and an efficient referral system developed. The National Library and the National Science Library maintain a general union catalogue of major library holdings of books and periodicals in the country. Additional special effort will be necessary to obtain adequate coverage of the primary non-medical drug use collections in Canada.

Coverage of the social science and humanities literature by the available technical abstracting and information services around the word is generally inadeqate. Attention is being focussed on this discrepancy in some countries, but much remains to be done to remedy this situation. The Federal Government should ensure that special effort is made to improve Canadian communication in this area. Recent efforts by the Social Science Research Council and the Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada to set up a data clearinghouse for the social and behavioural sciences should receive further support and guidance to ensure adequate coverage of Canadian non-medical drug use research needs in this area.

GOVERNMENT STATISTICS

There is a considerable body of national information on non-medical drug use available or potentially available to the Federal Government from its law enforcement, corrections, health and other statistics and activities. The Commission has had access to a great deal of useful information made available by various government departments, and has been impressed with the potential value of some of the existing federal data sources. Of particular interest are the drug sections of the Statistics Canada publications, Mental health statistics and Causes of death, the data from the Poison Control and Drug Adverse Reaction Programs, the Health Protection Branch drug analysis reports, various drug production, distribution and medical prescription data, and law enforcement and correctional statistics. Information from these and other federal and provincial data sources are discussed in detail in the various appendices which follow. Certain problems with the data are identified in those discussions and, in some instances, specific suggestions are made for improving the statistics.

In many cases, serious methodological, technical and practical problems limit the usefulness of the national government statistics presently available. We feel that a special effort should be made to improve the quality of drug-related data and to coordinate the collection and interpretation of related federal statistics. The frequent inconsistency in format used in reporting associated national data, even within the same department, and alternate use of fiscal and calendar year summaries often renders comparison and interpretation difficult. There is a great need for more uniform reporting of law enforcement, justice and correctional statistics. The delays involved in the present systems for the collection, collation, basic analysis, and publication of national statistics greatly reduce the value of the information. Greater effort should be made to automate and otherwise speed up the processing of such data.

If a major effort were made to generate more valid and useful national statistics, additional funds and staff would be necessary at various levels in the information collection and distribution process—often from the initial data source on up to the final analysis and publication stage at the Federal Government level. Such an endeavour would require considerable federal-provincial cooperation. In the health and criminal-justice areas, for example, national statistics are, in part, based on data abstracted and coded by provincial authorities from local reports, and consequently the Federal Government has little direct control over many basic aspects of the data.*

The International Classification of Diseases (ICDA) coding system, currently employed in the collection of much national health and death data, is in some respects ambiguous and inappropriate for the present North American phenomenon of non-medical drug use.f The Federal Government should work for appropriate revision of the classification system on an international scale, and proceed immediately to refine the presently available categories for future national statistics.

Although various collection, coding and communication limitations restrict the present usefulness of the non-medical drug use data available through the Poison Control and Drug Adverse Reaction Programs, these information systems provide a potentially invaluable source of epidemiological and pharmacological data.* We recommend that additional funds be made available to increase the utility of these programs, and that the Federal Government explore the feasibility of an integrated non-regulatory agency with a broader mandate for collecting, analysing, interpreting, and disseminating national statistics on adverse effects of chemicals on the human body.

In many instances there are inadequate communication channels or even explicit restrictions which inhibit the effective analysis and use of the available national statistics. In certain areas (e.g., information on drug-related deaths) provinces may restrict the subsequent use of detailed data provided to the Federal Government. Clearly, the citizen's right to privacy must be taken into careful consideration before data can be released for analysis. However, we feel that much could be done to improve government statistics, to make them more openly available and timely, and to facilitate and encourage the scientific analysis and communication of such information by independent and government researchers. Federal and provincial provision should be made for the release of health records and vital statistics for research purposes in a form which does not disclose the identity of the patients or subjects involved.

The Non-Medical Use of Drugs Directorate might usefully work with the various government agencies involved to monitor and improve national nonmedical drug use statistics and to aid in their routine interpretation.

FURTHER OBSERVATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS REGARDING THE NMUD PROGRAMS

We recommend that the preliminary efforts of the Non-Medical Use of Drugs Directorate to develop a special data base and information network receive further support, and that NMUD be given responsibility for the primary Federal Government initiative in ensuring adequate non-medical drug use technical information services on a national basis, following the general principles outlined in this section of the report.

We specifically recommend that the NMUD program provide national coordination among existing Canadian information resources, including both the specialized drug collections and the various general components of the overall federal STI system, and that it be responsible for identifying an filling the gaps in the collective network. Furthermore, NMUD should coordinate and improve access to relevant drug data collections and services in other countries. For example, certain major foreign alcohol and tobacco resources have not been tapped; they should be linked with the network soon.

Immediate action should be taken to establish working links with the major Canadian non-federal resources—in particular the facilities of the Addiction Research Foundation and the collections of OPTAT and Laval University. The holdings of the library and documentation services at ARF have recently been combined, and are in immediate need of further uniform indexing for retrieval. The Federal Government should provide consultation and financial support to ensure the efficient and continued availability of the ARF collection to Canadian researchers and other workers in the area.

The services of the national information system must be available at low cost to the user. Access to information and referral to data sources must be provided in a way which minimizes the problems often caused by geographic distance or institutional affiliations. Reasonable service must be made available from coast to coast. The services should be well advertised to the various potential users, and adequate instruction must be provided to enable users to make effective use of the system.

Further study will be necessary to determine which aspects of the total national drug information system would best be administered under central control and which components would more appropriately be included in an associated decentralized network. We support in principle the overall emphasis on decentralization in Canada's general STI policy.

As noted earlier, in the Interim Report we stressed that the national agency responsible for research and information be free of political pressure and responsibility for law enforcement, and perhaps independent of government in general. NMUD has no law enforcement role, but is not in principle free from potential political interference. We feel that a system which coordinates research and data resources, and distributes technical information to researchers and other experts can be adequately developed within the present NMUD government context. However, additional effort should be made to ensure that the process of evaluating data and preparing summaries and reviews is appropriately independent. We suggest that such work be supervised, and the resulting materials regularly reviewed, by an independent federal-provincial expert committee made up predominately of non-government scientists. The dissemination of the information should be subject to the committee's approval.

Some form of frequent national report or newsletter providing a general overview of current developments in non-medical drug use information would be invaluable to workers in the field. The Journal, a monthly drug information newspaper published by the Addiction Research Foundation of Ontario, has filled a major communication gap in this area. With further development, including more specific bibliographic documentation, it could provide an even more effective vehicle for rapid information dissemination to a wide range of people. The Federal Government should explore with the Foundation and other provincial authorities the possibility of supporting or "nationalizing" The Journal on a federal-provincial basis.

There is an apparent lack of appropriately trained science writers and reporters capable of effectively communicating technical information on drug use to non-experts and the general public. NMUD should support specialized training in this important area.

The Federal Government should explore, with the provincial governments and the various medical bodies, ways in which medical schools and associations can improve the education of physicians with respect to general, as well as treatment, aspects of non-medical drug use. Family doctors and general practitioners are commonly turned to for information in this area, in spite of the fact that most physicians have had little or no special education pertaining directly to non-medical drug use. As well, general non-science courses exploring the many facets of drug use in society would be a valuable addition to the general undergraduate and graduate curricula of universities in Canada.

NMUD should support scientists in the preparation of relevant literature review articles and books on a regular basis, and should regularly organize or fund conferences and meetings to maximize rapid communication. In addition, the Directorate might usefully provide a concise annual public report summarizing significant developments in its own activities; other Canadian research, education and treatment efforts; government policy and administrative regulations; various federal and provincial government statistics; and major foreign information.

NMUD should actively participate in the further development of Canada's general national and international scientific and technical information policy, to ensure adequate awareness and coverage of present and future needs in the field of non-medical drug use.

We suggest that the Federal Government's research and information policies and activities in this area be critically reviewed by an independent group, such as the Science Council, within three years of the release of this Final Report, and at regular intervals thereafter. Such evaluation should be made public.

* Interim Report, pp. 224-234.

* Some of the results of these studies are discussed in Appendix A The Drugs and Their Effects and in Tables A.8 and A.9 and note c to that appendix.

* Appendix A.1 Introduction, individual drug discussions, and notes b and c to that appendix; Cannabis Report, pp. 25-32; and Interim Report, pp. 228-229.

t Cannabis Report, p. 155.

# See Appendix A, note b, and the text of that appendix for discussion of this special study. What is needed to improve this project is not analysis of a greater number of samples than are currently included, but the development of a more systematic sample selection procedure and a clearer delineation of the seizure populations and samples involved. Furthermore, the special analysis might be expanded to include an occasional inquiry into possible herbicides, pesticides and toxic fungi in natural plant materials such as marijuana, and an assessment of insoluble particles in those drugs likely to be injected by the user.

§ On the other hand, the availability of data correlating chemical identification with adverse reaction symptoms might well provide a basis for the subsequent development of more drug-specific treatment methods.

* See Appendix A.2 Opiate Narcotics and Their Effects for discussion of immunoassay techniques.

t With the exception of LSD-PCP mixtures.

* Interim Report, pp. 224-234. t Treatment Report, p. 94.

# Cannabis Report, p. 161.

* With regard to national health statistics, see Appendix A and notes e and m to that appendix.

See Appendix A and notes e and m to that appendix.

* See Appendix A and note f to that appendix.

NOTES

1. Science Council of Canada: Towards a National Science Policy for Canada, Report No. 4, (Ottawa: Queen's Printer, 1968); University Research and the Federal Government, Report No. 5, (Ottawa: Queen's Printer, 1969); Policy Objectives for Basic Research in Canada, Report No. 18, (Ottawa: Information Canada, 1972); The Role of the Federal Government in Support of Research in Canadian Universities, Special Study No. 7 by John B. MacDonald, L. P. Dugal, J. S. Dupre, J. B. Marshall, J. G. Parr, E. Sirluck & E. Vogt, (Ottawa: Queen's Printer, 1969).

2. Senate Special Committee on Science Policy (The Honourable Maurice Lamontagne, P.C., Chairman), A Science Policy for Canada, Volume I, "A Critical Review: Past and Present," (Ottawa: Queen's Printer, 1970); and Volume II, "Targets and Strategies for the Seventies," (Ottawa: Information Canada, 1972). A third and final volume of the Committee's report series has been completed and is scheduled to be released to the public early in the fall of this year.

3. Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada (Louis-Philippe Bonneau & James Alexander Corry), Quest for the Optimum, Volume I, (Ottawa: Mutual Press Limited, 1972) and Volume II, (Ottawa: Mutual Press Limited, 1973).

4. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, Reviews of National Science Policy, (Ottawa: Queen's Printer, 1969).

5. See "SCITEC Forum on Science Policy: The Many Voices of Canada," Science Forum, Special Supplement 31, Volume VI, No. 1, February 1973.

6. Science Council of Canada: A Policy for Scientific and Technical Information Dissemination, Report No. 6, (Ottawa: Queen's Printer, 1969); The Role of the Federal Government in Support of Research in Canadian Universities, Special Study No. 7 by John B. MacDonald, L. P. Dugal, J. S. Dupre, J. B. Marshall, J. G. Parr, E. Sirluck & E. Vogt, (Ottawa: Queen's Printer, 1969) ; Scientific and Technical Information in Canada, Special Study No. 8, Parts I and II by J. P. Tyas and Associates, (Ottawa: Information Canada, 1972), pp. 1-28.

7. Canada, Task Force on Government Information, To Know and Be Known, Volume I & Volume II, (Ottawa: Queen's Printer, 1969).

8. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, Review of National Scientific and Technical Information Policy, (Ottawa: Information Canada, 1971).

9. National Research Council of Canada, Reports of the President, 1968-1969, 1969-1970,1971-1972.

10. E. Polacsek, "A National Information System on the Non-Medical Use of Drugs," Unpublished Commission Research Paper, 1970; E. Polacsek, "Sources of NOMED Information," Unpublished Commission Research Paper, 1971; C. G. Farmilo, E. Polacsek, E. Hanna, L. Barash, G. Larsson & I. Stankiewicz, "Scientific, Technical and Social Information on Non-Medical Use of Drugs," Unpublished Commission Research Paper, 1971; R. D. Miller, "Scientific and Technical Information," Unpublished Commission Research Paper, 1973.

11. H. D. Beckstead & W. N. French, Some Analytical Methods for Drugs Subject to Abuse, (Food and Drug Directorate, Department of National Health and Welfare), August 1971.