| - |

Drug Abuse

C.4 PATTERNS OF USE

In discussing the process whereby persons become introduced to and involved in, and depart from the use of drugs, it is helpful to employ the concept of a 'social career' as delineated by Becker and others.15, 96, 268, 278 The notion of 'career' permits the understanding of behaviour patterns as developing in an orderly sequence that any individual may pass through—for example: 'experimental', 'occasional', and 'regular' drug user. Attainment of each step in the sequence is a necessary condition for further career advancement, although this developmental process may be terminated or reversed—with varying difficulty, depending on the drug—at any stage.

The concept of a drug career, however, does not necessarily imply that a particular variety of drug use assumes a predominant or determining role in an individual's life. In some cases, of course, this actually occurs—heroin, methamphetamine ( `speed') and alcohol dependence being the archetypal examples of this development. In most instances, however, a person's drug-using career is subordinate to other aspects of his life (his academic, occupational and familial careers, for example) and patterned by these conventional demands and obligations. A drug-using career, then, is simply a natural history of drug use: that orderly sequence of stages through which any individual may progress between initial and chronic use of a drug.

It is possible to describe individual career routes for every psychotropic drug. This approach, however, would tend to hinder appreciation of the fact that the process of drug use socialization is basically the same no matter which drug or drug-type is considered. For this reason, the following discussion applies generally to all drugs. There are, however, junctures at which it is critically important to distinguish specific drugs and drug careers from this general framework. In such instances, the differentiating properties will be

discussed and, when necessary, particular career patterns associated with specific drugs or drug combinations will be more comprehensively developed.

Drug use—like any social, recreational or vocational activity—is learned behaviour.* Consequently, the process of becoming a drug user is essentially identical to the learning of behavioural patterns within any sociocultural context. In the case of drugs, a novice must first learn to accept the idea of his personal use of drugs. Subsequent use is likely to depend on learning to acquire, prepare and administer drugs, learning to subjectively appreciate their effects, and learning to accept their use as appropriate behaviour under certain circumstances. The regular use of a drug requires learning the role of `drug user' and, in some cases, learning to become a member of a drug-using subculture. The discontinuation of, abstinence from and relapse to the use of drugs also involve learned behaviours. Learning, then, includes many aspects of drug use: ingestion, patterns of use (frequency, drug preferences, social contexts), meanings of the drug experience, ideology and values, and a host of esoteric skills related to the procurement of drugs and, in some instances, the maintenance of a drug dependence.

This socialization process can best be described with reference to a typology of drug users based on levels-of-drug-use (see C.1 Introduction above). These level-of-use distinctions—initial or experimental use, occasional use, and regular use—can be viewed as three identifiable gradations on a continuum of increasing personal involvement with drugs and drug-related activities. These level-of-use categories can also be conceived of as three stages of socialization into drug use, albeit with the caution that progression to any advanced stage is neither irreversible nor a necessary or inevitable consequence of entry into a preceding stage.

INITIAL OR EXPERIMENTAL USE

`Experimental' users of a drug are those persons who have not yet learned to effectively use and positively interpret the effects of the drug in question. They usually have no regular access to supplies of the substance, and they are unlikely to have assumed the definitions and evaluations of the using culture. Persons who try a drug but never learn to recognize or appreciate its psychotropic effects are unlikely to advance to occasional use of the drug. They will, instead, terminate their use after a few experimental sessions.

As was pointed out in the Cannabis Report with respect to marijuana and hashish, the initial use of a drug almost always depends on a willingness to try that drug.* The exact motivating factors—whether psychological or sociocultural—that predispose an individual to drug use may vary from drug to drug and from individual to individual (see Appendix D Motivation and Other Factors Related to Non-Medical Drug Use). However, the willingness to initially experiment (whatever its etiological source) depends on the potential user's interpersonal and attitudinal situation (discussed on the following page) and his effectively dealing with three major social control mechanisms: limited availability, the need for secrecy, and the relative immortality of the act as publicly defined.'3. 14 Advancement through the stages of a drug-using career will only occur once any inhibiting effect of these controls has been successfully neutralized.

It is important to recognize, however, that the valence or strength of these controls varies from drug to drug, from reference group to reference group, and from time to time. Alcohol and tobacco products, for example, are much more readily available than are the illicit drugs—although access to these substances is still restricted by legal regulations and more informal familial rules that primarily affect use by children and adolescents. Similarly, the need for secrecy resulting from the fear of disapproval or other negative sanctions does not usually apply for most adult use of licit psychotropic substances, but would have some inhibiting effect on most illicit drug experimenters and those adults who dwell in communities which express and follow temperance values. It should be noted, as well, that conventional definitions of appropriate drug-using situations compel many adult users of licit drugs to be secretive about their consumption; for example, a business executive anticipating a tense conference may imbibe alcohol in the privacy of his office in order to keep his co-workers from learning of his indulgence and commenting unfavourably. The non-medical use of 'pep pills' by housewives, athletes and businessmen may also be hidden from friends and relatives for similar reasons.

Public definitions of various types of drug use also change over time and, consequently, alter the moral context of such use and the inhibiting force of these moral considerations. Cannabis use, for example, has recently been divested of many of its negative moral connotations, while the non-medical use of amphetamines has suffered increasing stigmatization over the past few years. Despite these variations, it appears that initial drug use depends on the neutralization of these three social controls—although some types of experimental use are more easily arranged and justified than others.

The problems of availability, secrecy and stigma are usually resolved within the context of initial drug use. Obviously an individual's willingness to try a specific drug is at least partially a function of his previous drug experiences, if any,* and some degree of anticipatory socialization that predefines the event as relatively attractive or unattractive. Once one is open to a drug experience, however, his actual use of the drug is more likely to occur in an aleatory—although natural—rather than deliberate fashion. Furthermore, one's initial experience with a specific drug—regardless of the drug or previous drug experiences—is likely to transpire in a social situation in which such behaviour is both tolerated and typical. As Sadava has noted: "The crucial point to be made here is that drug-using behavior . . . is not [usually] a sudden dramatic change in the individual's life and values, but develops as a natural, i.e., not surprising, process within the sociocultural context."229

Alcohol use, for example, is likely to begin in early or mid-adolescence, with parental permission being granted to test small amounts of the drug in the household living or dining room. Alternatively, a teen-ager may be introduced to alcohol by his peers at a party or after school. In either case, the problems of availability, secrecy, and stigma are resolved by influential friends or relatives who sanction the activity, furnish the drug, and provide a setting relatively safe from legal intervention. The initial use of other drugs occurs in a similar manner, except that parental influence is often replaced by the influence of trusted drug-using friends, relatives or a single intimate (such as a spouse or lover) in the case of illicit substances.

The naturalness of this initiation process is clearly evident in the case of heroin—the most stigmatized and one of the least accessible of all currently used drugs. Many researchers report that a close, friendly association with heroin users almost invariably precedes first use of the drug.36, 57, 73, 121, 147, 150, 253, 268 Initial use, when it does occur, is usually (but not always) a spontaneous and unanticipated event in which the experimenter is often gratuitously provided with an opportunity to try the drug.57, 117. 121, 150 The novice's initiators are most often experimental or occasional users themselves who—by virtue of their non-dependent state—claim to be in control of their heroin use.]' Thus, the initiators mitigate the new user's anxieties about the potential dangers of heroin use by presenting themselves as 'living proof' that dependence does not necessarily follow even extensive experimentation.268 Furthermore, the drug is sincerely offered to non-users as a pleasant experience rather than out of any desire to cause harm or injury. As Hughes and Crawford, in a recent study of heroin initiation and diffusion in Chicago, have observed:

... initiation to heroin usually occurs in a small group setting, involving only the new user and one or two addicts or experimenters. Most frequently, the initiate is introduced to heroin when he meets a friend who is on his way to cop [purchase] or is preparing to "fix" [inject]; he rarely seeks out the drug the first time. Thus, initiation depends more on fortuitous circumstances than on a willful act by the new user."'

It should be noted, however, that—theoretically—the first use of a drug need not derive from social interaction with users of that drug. Initial use may also occur as a consequence of accidental discovery of a substance's psycho-tropic effects (as occasionally occurs with the volatile solvents) or as a result of exposure to media presentations or hearsay which leads to a deliberate decision to obtain and try the drug. However, except for certain licit drugs (such as most solvents, some hallucinogens such as nutmeg, alcohol, tobacco, and pharmaceutical preparations such as amphetamines and sedatives which may be removed from family medicine cabinets) and certain privileged populations (such as the medical profession), the problem of availability remains and, consequently, almost all initial drug use results from interpersonal introductions to the drug. The Commission's university survey, for example, found that only three per cent of Canadian college cannabis users had first tried marijuana or hashish by themselves.'"

The one major exception to the social and fortuitous nature of this initiation process involves those persons who purposefully and privately employ drugs for self-medication or improved functioning. Members of the medical profession—who are familiar with the medical properties of drugs and who have constant access to them—constitute the best documented example of this practice. Whereas illicit drug users generally experience initiation in a primary group setting, doctors and nurses almost always first ingest or inject their drugs in isolation and attempt to maintain the secrecy of their use. By way of illustration, Winick found that not one of his sample of 98 ,physician-addicts had been introduced to opiate use by others, and that 25 per cent of the doctors' wives were unaware of their husbands' dependence.277 It appears, then, that in the case of doctors, professional training and occupational access to drugs substitute for the interpersonal socialization that characterizes most types of drug initiation.

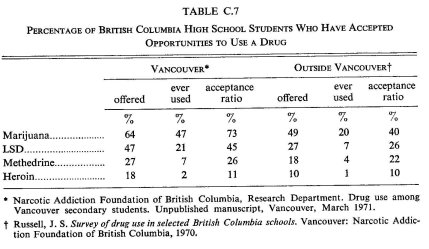

While availability is obviously a crucial factor in initial drug use, it is clear that only a fraction of those persons granted an opportunity to try a drug actually do so. Goode has reported that 46 per cent of his sample of 200 marijuana users had declined opportunities to try marijuana prior to their initial use," and a Commission survey of Canadian adults found that only 25 per cent of those respondents who had been offered LSD had in fact used this drug. 142 Furthermore, it appears that the proportion of those who accept an offer to try a drug is inversely related to the perceived danger or stigma of that drug: the greater the perceived danger or stigma, the lower the proportion of users among those who have access. Table C.7 illustrates this relationship for two British Columbia high school populations.

Goode has suggested that the decision to experiment with a new drug is dependent on the novice's perception of the relative danger involved in such use, his perception of the drug's benefits, his attitude toward users of the drug, and his closeness to both the drug's endorsers and those who have proposed the.initiation.99 Several investigators have reported that the most important determinant in regard to initial experimentation is the degree of `trust' that an initiate feels for those offering him an illicit drug.48• 59, 63, 230

In some cases, a particular mode of administration may have as great —or even greater—an inhibiting effect on initial use of a drug as the novelty of the drug itself. Previous drug experiences play an important role in this regard: users of tobacco products are unlikely to balk at the prospect of having to smoke marijuana, hashish or opium, and the swallowing of a pill, capsule or tablet (as is the ordinary mode of ingestion in the case of hallucinogen and sedative use) is such a universal procedure that few, if any, novices would hesitate to use a drug because of this administration technique. However, other modes of administration—such as the 'snorting' (nasal inhalation) of cocaine or the use of plastic bags with certain volatile solvents—may be sufficiently alien to many persons to at least intially deter them from such experimentation.

The most dramatic illustration of the inhibiting force of administration techniques concerns the use of drugs that are usually used parenterally (i.e., by injection) such as heroin and 'speed' (meth amphetamine). These substances may be snorted rather than injected, but an initiation opportunity is most likely to occur in a setting in which experienced users are intravenously using the drug. Parenteral techniques (be they subcutaneous, intramuscular, or intravenous) are generally considered painful and, as such, are anathema to most persons whose modes of drug administration, if any, ordinarily consist of swallowing or smoking. For those individuals who have previously injected drugs (usually hallucinogens), the transition to intravenous use of speed or heroin is not difficult. But, for most, this style of use represents a critical departure from their normal drug consumption patterns. One Montreal speeder clearly expressed the significance of such usage:

When you start using a syringe that indicates that you're using heavy drugs—that you're really into the drug scene. The syringe is the cutting off point between soft and heavy drugs."'

Despite these apprehensions, most persons who have an opportunity to try speed or heroin and have decided to do so will allow an experienced user to inject them once their fears have been verbally or demonstrably allayed.

It is reasonable to assume that someone interested in initially trying an illegal drug will usually take either the first one which is offered to him by trusted friends or that drug which he considers the least dangerous of those available to him in his social milieu In many cases, cannabis is the first illegal psychoactive drug to which an individual will have access, but the use of one or more of a wide range of other drugs usually predates marijuana or hashish use. Various studies have shown that the use of prescription drugs, barbiturates and amphetamines, glue and other volatile solvents, tobacco and alcohol often precede the use of cannabis.

When questioned about their early drug history, the majority of nonmedical users reveal that their first experience was with alcohol. In the mid-fifties, Stevenson and his associates found that almost all of the British Columbia heroin users they studied had used alcohol prior to opiates and most of them had never tried cannabis.263 As noted earlier, it was not until the mid-sixties, when cannabis became readily available in western Canada, that heroin users indicated concurrent or prior use of marijuana.127 Alcohol, as the first drug used by heroin addicts, has been reported by Henderson, Chambers, Robins, Darvish and Murphy, and Kosviner, et al.52' 117, 137'215 Hawks and his associates discovered that problem drinking predated the use of other drugs among amphetamine users;113 Whitehead found that alcohol and tobacco use generally precede solvent use;274 and cannabis-using college students studied by Goode had first used alcohol.99 Moreover, two extensive surveys; one of a college population238 and the other of high schools," found that alcohol-using students were much more likely to want to try marijuana than were non-drinkers.

Heroin users have often consumed a wide variety of other drugs prior to opiate use.268 In Vancouver, Johnston and Williams found that in one sample of 186 heroin users, 11 per cent had first used amphetamines, 20 per cent first used hallucinogens, and 32 per cent first used barbiturates, while the remainder (37 per cent) had used cannabis first.127 These respondents, however, were not questioned about their use of alcohol or tobacco. It is evident that for almost all adolescents, the first psychotropic drug used is either alcohol or tobacco."° Unfortunately, many investigators do not ask about these drugs when collecting drug-use histories of their subjects. Although tobacco and alcohol are legally distributed, the first use of these drugs is often by children or adolescents who are under the minimum legal age.

The use of a number of other legal substances may also predate illegal drug use. A number of studies have discovered that the non-medical use of codeine cough syrups has preceded the use of illicit substances.14°. 166 Barbiturate use has often been found to precede the use of other 'dangerous drugs' and heroin.103, 282 Glue and solvent sniffing may often occur before the use of cannabis or other legally prohibited substances. The relationships among various patterns of non-medical drug use are further discussed in C.4 Patterns of Use, "Patterns of Multiple Drug Use".

OCCASIONAL USE

In the Cannabis Report occasional users were defined as those persons who consume marijuana or hashish once a month or less. Such operational definitions, however, are inappropriate to a discussion of patterns of drug use in general, as level-of-use distinctions based on frequency and regularity of use are a function of the effects of the drugs being considered, their relative availability, and their legal status. For our purposes then, occasional use will be understood as that using pattern characterized by episodic consumption dependent on fortuitous developments such as the sharing of another's drug in a social setting. Occasional users do not usually maintain a personal drug supply and the use of psychotropic substances has only a marginal role in these persons' lives. Generally speaking, the occasional use of drugs represents a recreational diversion that is approached with a 'take it or leave it' attitude.

The occasional consumption of a drug is usually the first stage of continued drug use beyond initial or experimental use and, as such, is dependent on learning to effectively use and positively interpret the effects of the drug. There are several learning processes which are generally considered prerequisites to any continued use of a psychotropic substance. These include mastering the modes of administration necessary to achieve a desired drug effect, learning to perceive these effects as drug induced,* and learning to subjectively interpret these effects as pleasurable or functional and, therefore, worth at least occasional repetition. These 'lessons' usually result from participation with more experienced users who educate the novice as to the most effective means of consuming a particular drug and sensitize him to those psychological effects which they value and which positively reinforce their continued use. This social education of an occasional user is also likely to include information about safe dosage levels, appropriate behaviour, legal precautions (if necessary), and those activities which are felt to be enhanced by use of a particular drug.

Apart from the desire to be stylish or to avoid embarrassing oneself or one's host, any continued use of a drug—be it occasional or more regular —depends, at least, on the internalization of these first lessons: learning to correctly use a drug, and learning to recognize and appreciate its effects. In the case of some drugs, however, an occasional—rather than regular—consumption pattern may reflect limited availability, prohibitive costs or fear of legal intervention, rather than the 'take it or leave it' attitude that ordinarily characterizes this level-of-use. Cocaine, for example, is often reported as a favourite drug by persons whose financial situation or range of drug-using acquaintances restricts their use to those infrequent occasions when they are fortunate enough to come into contact with persons who possess the drug. In cases such as this, the drug is strongly desired and a regular pattern of use is only avoided because of situational rather than motivational factors.

Finally, it should be noted that the occasional use of a drug may follow as well as precede a period of regular use. This possibility is discussed below in the context of termination and reduction of regular drug-using patterns.

REGULAR USE

Although many individuals remain on a level of drug use that is occasional, spontaneous and serendipitous, for others use becomes a regularized pattern governed by normative restraints. Alcohol is a case in point. For some, it is only used in exceptional circumstances; for others, alcoholic beverages will become a natural adjunct to certain activities or will be consumed on specific occasions in a regular fashion, before dinner or while watching sporting events on television, for example. This does not mean that alcohol will always be a part of these situations, but there is a higher likelihood that it will be used then than at other times.

Not all drugs are used regularly in the same way. Coffee, tea or tobacco are usually consumed throughout the day. Similar patterns of alcohol use are less common and generally restricted to those who are considered in North American society to have a 'drinking problem'. However, regular or ritualized daily use of moderate quantities of alcohol (taking wine with meals, for example) is not considered by most people to be an incontinent level-of-use. With regard to illicit drugs, recent studies of regular cannabis users tend to suggest that patterns of use of marijuana or hashish are somewhat similar to those of alcohol, and that for some users these substances are essentially social or functional equivalents.'87 Frequent use of LSD or cocaine, on the other hand, is a comparatively rare phenomenon for reasons specific to the effects or the availability of these drugs.

The usual levels of regular use that are attained by non-medical drug users vary according to the kinds of substances that are consumed. In the Cannabis Report we operationally defined 'heavy-regular use' as smoking cannabis from twice per week to several times per day. For this substance this is a reasonable definition that would be accepted by most researchers as well as a proportion of users themselves. However, for a substance such as tobacco, even two or three times per week or one cigarette per day would be considered a moderate to light level-of-use compared to the use levels of most tobacco smokers. Similarly, 'moderate-regular use', as we have earlier defined it, may involve the ingestion of cannabis several times per week. This would probably be a reasonable and meaningful operational definition of moderate-regular alcohol use, as long as the doses were not excessive, but would represent a heavy use pattern for a drug such as LSD. Thus, each drug requires its own operational definitions of what constitutes 'light-% 'moderate= or `heavy-' regular use.

Some regular drug use patterns involve daily or even hourly administration; others entail less frequent use, but are nonetheless 'regular' insofar as the drug is usually taken in specific situations or under certain conditions. For our purposes, 'regular use' is any pattern of drug use that involves systematic consumption of a drug, even if the frequency of use is quite low. Regular drug use assumes that the individual has developed a set of norms or rules governing the appropriate times and places for drug use as well as the usual dosage levels. In many cases, official and unofficial rules not only regulate drug-taking behaviour, but also behaviour while under the influence of these substances. In the light of this definition, ceremonial or ritual use of drugs (such as alcohol and peyote) is one type of regular use pattern, even though it may only occur once or twice per year. Thus regular use may involve heavy or high-dose use, but these use levels are not necessary conditions of regular use patterns as we have defined them.

BECOMING A REGULAR USER

There are a number of factors which affect the likelihood of establishing a regular use pattern, the dosages likely to be consumed and the frequency and situations of drug administration. In the following section we will deal with those variables which govern the ease or difficulty of adopting behavioural norms of regular non-medical drug use.

THE LEGAL FRAMEWORK

Although alcohol is one of the most popular drugs in non-medical use in Canada, local laws and statutes restrict the times during which it can be purchased (in some 'dry' counties, banning purchase altogether) and the situations in which the beverage may be consumed. There are also restrictions on the age of the users. Some of these restrictions are circumvented, disobeyed or rarely enforced (the public consumption of alcohol at sporting events, for example), but they still act as constraints on the drinking behaviour of most people. In addition to regulations governing when and where alcohol may be drunk, there are also restrictions on what activities an individual may participate in while under the influence of alcohol, from operating a motor vehicle to being 'drunk and disorderly' in a public place. The purchase of tobacco products is restricted to those over a certain age limit, but otherwise there are few legal restraints on its use other than forbidding smoking in certain theatres, public buildings or conveyances. Coffee, tea, and over-the-counter preparations are universally available and governed only by controls on their manufacture, advertisement and wholesale distribution. There are literally thousands of products on the shelves of retail stores which contain solvents or propellants which may be used for their psychotropic effects. They remain readily available for socially approved purposes, thus making legal control of their use for intoxication extremely difficult. Illicit drugs are much less readily available to most users.

AVAILABILITY OF DRUGS

In order to establish a regular drug use pattern, it is necessary to obtain a sufficient and relatively continuous source of supply. For some users, this source will necessarily be illegal or quasi-legal. Adolescents who have not yet attained the legal drinking age or are too young to purchase tobacco must rely on adults or older adolescents to obtain these drugs for them unless they appear to be older than their years or have been able to obtain forged or stolen identification certificates or those of older friends. For many substances, there is no legal source for the non-medical drug user.

Becker proposed that obtaining a regular source of supply of cannabis was one of the most important aspects of becoming a regular marijuana user." The necessity of establishing a source of supply is an important factor in becoming a regular user of all illicit drugs, although some substances are more readily available than others. Over the past few years, many drugs which were once difficult to procure have become readily available from a wide variety of sources.

Most non-medical drug users are introduced to the use of their drugs by friends or acquaintances and these friends are also likely to serve as sources of access to the illicit market. In some cases the first regular contact with an illicit marketplace will occur when a group of friends pool their purchasing resources, thus reducing the unit price of the quantity each uses for personal consumption.99 Cannabis and LSD users are particularly likely to purchase a specific amount for use over a period of weeks or months, thus reducing the frequency of their contacts with the illicit market, although taking on the additional risk of having 'stashed' drugs found in their possession. Regular heroin and high-dose methamphetamine users are more likely to buy in smaller quantities and generally use up their purchases almost immediately.

Illicit drugs are not equally available to all drug users. Most individuals who have reliable contacts to obtain cannabis do not know—or care to know—anyone from whom they can purchase speed or heroin. The dealers of most drugs are understandably cautious about selling to strangers and usually require that a regular customer introduce any new purchasers to them. In the case of heroin, a dealer may ask for proof that a stranger is a user of the drug before he will sell to him.47, 254 In a study of heroin users who did not become chronic users of the drug, Schasre discovered that over one-half of the ex-users stopped taking heroin as a result of losing their source of supply.231

For some drugs such as opium and cocaine, the expense of the drug and its relative scarcity in Canada militate against establishing regular consumption patterns. Except for a few wealthy dealers and 'rich hippies' who can afford these drugs and have access to a source of supply, cocaine and opium are considered to be 'treat' drugs, consumed only occasionally in Canada when they become available.104

Although many people begin the use of sedative-hypnotics, tranquilizers or oral amphetamines through doctors' prescriptions, if regular use ensues they may be forced to resort to diverted supplies of these drugs which are purchased on the illicit market. Others may first obtain pills from their friends or the illicit market and later attempt to obtain them legally by convincing doctors to prescribe them.

PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGICAL EFFECTS

One of the major reinforcing factors which encourages repeated administrations and regular use of drugs is derived from their specific physiological and psychological effects. For example, although unpleasant first reactions to heroin are common, some users of this drug claim that their first shot made them feel the way they had always wanted to fee1.145, 253 For others, a drug may simply be a pleasant experience that warrants repetition in certain social situations. Needless to say, not everyone finds each drug experience to be immediately rewarding, and negative reactions or side effects are a major factor in discouraging repeated use of most drugs.

Because of their dependence-producing effects, certain substances require daily use once a particular level of consumption has been reached. Dependence on the opiate narcotics is considered to be the 'classical' case of drug dependence, and a great deal of research has been conducted to determine the etiology or cause of this condition. (See Appendix D.2 Motivation and Other Factors Related to Opiate Narcotic Use.)

In the mid-forties, Lindesmith developed a theory of opiate dependence which he proposed would explain all cases. He concluded that opiate dependence occurs when an individual learns the meaning of withdrawal distress and consciously uses an opiate to relieve these symptoms or prevent them from occurring.15' After tolerance has developed, the organism requires the drug to function smoothly and, if it is not regularly administered, withdrawal symptoms of varying intensity are experienced. The appearance of these symptoms is crucial to Lindesmith's argument. If they are misinterpreted as some other ailment (a common occurrence when opiates have been medically administered in hospital and withdrawal discomfort is interpreted as a result of the original pathology) dependence does not occur. Similarly, persons who have been experimenting regularly with illicit heroin may interpret their first withdrawal symptoms as a common cold or the flu.145 It is only when an individual experiences the distress, realizes or learns that it is due to the absence of opiates in his body, and administers the drug to relieve his condition, that the complex of attitudes and behaviour which constitutes dependence appears. According to Lindesmith, it is at this point that an individual first comes to see himself as an opiate dependent.

Whereas drug use is generally believed to be sustained by the positive, euphoric effects of the substance, Lindesmith's work suggests that dependent drug use is also negatively reinforced by withdrawal avoidance. In other words, dependent drug use may be seen as a form of continuous self-medication or anticipatory self-medication.192 There is some difference of opinion about which drugs, at what use levels, can be said to be used this way rather than solely for their euphoric effects, but we assume that avoidance of unpleasant withdrawal symptoms is an important element of some levels of tobacco, alcohol, amphetamine, barbiturate, opiate narcotic and other drug use, especially, but not only, at daily levels-of-use.

Although the onset of physical dependence has a profound effect on use patterns and life styles of certain drug users, it is not a factor in the drug-taking behaviour of the majority of regular users of most drugs. For these, the frequency with which they indulge and the quantities of the substances involved are regulated by social interaction and normative restraints which are developed over time.

SOCIAL FACTORS

In an earlier section of this appendix we explained that initial and occasional non-medical drug use, like many other activities, is usually learned in a social context. In many instances, regular drug use patterns also become established and reinforced through social interaction. For example, an individual who is using cannabis, LSD or some other hallucinogen from time to time may acquire more friends who use these substances. This increases the likelihood that he will use more often and under more diverse circumstances. With an increasing number of opportunities to use and purchase drugs, the occasional user may be encouraged to use a drug more frequently and may eventually establish a regular use pattern by which he determines which situations are appropriate for cannabis or LSD consumption and which ones are not, as well as the amounts to use to maximize the effects desired in specific instances. He may come to believe that cannabis use increases the enjoyment of eating and make it a regular pre-dinner ritual in the same way that others will enjoy an aperitif. He may be encouraged to take LSD during an excursion to the country and decide that this experience is much more rewarding than the use of hallucinogenic drugs in the city and should therefore be restricted to rural settings. On the other hand, he may determine that his friends or acquaintances seem to use certain drugs indiscriminately or to excess, and decide to limit his use to specific recreational contexts. A similar process can be observed with persons who decide, through interaction with friends and acquaintances, what situations are appropriate for drinking alcohol, inhaling solvents or taking a number of other substances.

The influences stemming from the drug taker's social milieu which will eventually help to determine his pattern of regular drug use can be summarized briefly as follows:

1. Information. Friends and relatives may offer information on situations in which certain substances may be used for specific purposes. For example, it may be suggested that cannabis or LSD would increase the enjoyment of certain movies or concerts or that an over-the-counter or prescription drug can be used to self-medicate adverse drug effects or potentiate the effects of other drugs.

2. Example. The occasional user may learn by watching the behaviour of his peers what sorts of situations are appropriate for certain kinds of drug use, and what levels of use can be deemed excessive. Others may show by their example that no observable harm or disruption is likely to result from certain levels-of-use.

3. Ideology. Participation in drug-using groups provides supporting ideologies which neutralize some of the negative opinions and attitudes surrounding illicit drug use and provide positive reinforcement and justifications for drug-taking behaviour. For example, cannabis users commonly rationalize their behaviour through the belief that legal substances such as alcohol and tobacco are much more harmful and that smoking cannabis is a minor vice in comparison.13

4. Opportunity. The more people in the environment who use drugs on a regular basis, the more likely it is that opportunities to use will arise at times when the individual may not otherwise have thought of consuming a drug, and that he will discover more sources of supply of illicit drugs.

PSYCHOLOGICAL FACTORS

Although levels-of-use are often largely determined by interaction with friends and relatives, certain people evidently establish regular use levels at variance with those of their peers or seek out peer groups which have quite different patterns of non-medical drug use. The personality variables which may affect these decisions are discussed elsewhere in this report (see Appendix D Motivation and Other Factors Related to Non-Medical Use). It is sufficient to mention in this context that there are numerous personality factors and events in the personal life histories of some non-medical drug users which help to explain their regular use patterns as well as the inclusion of certain drugs in their pharmacological repertoire.

PATTERNS OF REGULAR DRUG USE

Patterns of non-medical drug use are numerous and varied, depending on the substances involved, their legal status and availability, their psychopharmacological effects, and a number of other factors. In addition, most substances are used in various ways by different people or by the same individuals over time. In the following pages we delineate three major types of regular non-medical drug use: functional, recreational, and dependent. Although each of these categories will be described separately, they are not to be understood as discrete types. Some drugs, alcohol for example, may be used in all three ways. Some people may use a specific drug in one or more of these ways at the same time or gradually shift from one pattern to another over a period of time. This typology does not necessarily constitute every possible drug use pattern, past and present, but is designed as a framework within which the major patterns of non-medical drug use may be described.

Functional drug use involves the consumption of a substance with the specific intention of utilizing one or more of its physical or psychological effects for reasons other than the pleasure or euphoria which the drug may provide. Some drug use may be considered functional in that it facilitates social interaction. However, for our purposes, instrumental or functional drug-taking behaviour will refer to those patterns of use in which the primary intention is to increase task-oriented efficiency or to relieve unpleasant mental or physical conditions. Functional drug use, then, is individual rather than social and specific goal oriented rather than recreational. Recreational drug use, on the other hand, encompasses those non-medical drug-taking activities which are primarly oriented to the pleasurable psychological effects of the substance and are usually restricted to social activities and leisure hours. Dependent drug use usually involves a degree of loss of control over use levels and a strong compulsion to use a drug; thus use may occur in any setting, regardless of the social situation or the immediate mental and physical state of the user.

FUNCTIONAL DRUG USE

Task performance. Drugs of the stimulant category are commonly used with the intention of increasing alertness in task performance. The most common of these are caffeine (which is consumed in coffee, tea, cola beverages and over-the-counter `wake-up' preparations) and the nicotine in tobacco products. Although coffee and tea are also used in a recreational context, their effects are employed for stimulation, both consciously and unconsciously, by most users.33 The well-established institution of the 'coffee break' is usually a social occurrence, but the substance consumed also performs secondary energizing functions.

Stimulants are sometimes used by members of certain occupational groups whose jobs require intense physical activity, alertness or endurance. Amphetamines and amphetamine-like substances are most commonly taken for this purpose by waiters and waitresses,104 taxi drivers and long distance truck drivers,83 104 and professional athletes.". 00. 91, 92 Students are also known to take them in order to stay awake and `cram' for final exams.21, 89, 249, 270 Certain medical practitioners have been accused of complicity in the development of this type of non-medical drug use. For example, cases have been reported of doctors who administer `vitamin shots', virtually on demand, to their patients. These injections not only contain a number of vitamin supplements, but also quantities of amphetamines.209, 210, 280

It appears that any form of mood-modifier, whether a stimulant or a depressant, can be perceived by some users to be a means of increasing task-oriented efficiency or performance. Although such use is not well documented it can be assumed that in some cases tranquilizers, barbiturates and low doses of alcohol may be used in this way. Doctors and other medical professionals who become dependent on opiate narcotics often assert that they began use in order to counteract fatigue caused by overwork."6. 277

Self-medication. Self-medication is a form of non-medical or quasi-medical drug use which involves the use of psychotropic substances to ameliorate certain mental conditions or psychological discomfort, or to treat physiological problems. Usually there is little or no medical supervision involved. Alcohol is commonly used for self-medication—a drink before dinner for its tranquilizing effects after a busy day, for example. Cannabis is sometimes smoked to relieve the secondary symptoms of a cold or the flu (see Cannabis Report). A number of over-the-counter preparations, such as codeine pills or cough syrups, antihistamines and other substances are used not only for their stated purposes but also for reduction of nervous tension or to induce sleep.

This type of drug use may originate from medical supervision; a physician may prescribe a preparation for the treatment of an allergy and the patient may use it, either consciously or unconsciously, for tension management or sedation. People who initially obtain `diet pills' to lose weight may take them to combat depression. Similarly, sedatives and tranquilizers are sometimes used for purposes not intended by the prescribing physician. It is often difficult to distinguish between medical use and this quasi-medical type of self-medicating drug use, but it is nonetheless clearly distinct from social or recreational drug use.

One of the more common forms of self-medication involves the treatment of drug effects or after-effects with the use of another drug. This type of cyclical multiple drug use is discussed in a later section of this appendix. It constitutes an important type of functional drug use as well as a major pattern of multiple drug use.

RECREATIONAL USE

Recreational drug use involves the consumption of a substance, usually in a controlled or non-compulsive manner, during leisure hours. The drug is taken for the purposes of attaining a measure of euphoria, increasing the enjoyment of other leisure pastimes or as an aid to social interaction. Although some recreational non-medical drug use is solitary, in most cases it takes place in the company of family or friends.

Social recreational drug use usually takes place among people who share ideas, attitudes and friendship in addition to their preferences in pharmacological substances. Drug use of this type usually begins in a pre-existing peer group, and regular use levels are often maintained in this same context. Some drug users (heroin dependents and high-dose intravenous methamphetamine users, for example) are likely to move into new drug-using circles when regular use becomes established, but most recreational drug use takes place in groups of like-minded people who would have been associated even if they did not use drugs regularly.

Barbiturates and other sedative-hypnotics are sometimes taken by multiple drug users in social settings, for euphoria or to potentiate the effects of other drugs. Low doses of methamphetamine or 'diet pills' may be used to stimulate or prolong social interaction. Regular use of these drugs, however, is not usually confined to recreational settings.

Sniffing glue and other volatile solvents appears to be primarily a recreational form of drug use. There is little data available on the solitary solvent sniffer and, although this pattern of use is known to exist, most of the literature describes the social use of these substances by adolescents or children within a peer group context.12, 37

Heroin is usually initially used as a social and recreational drug, but this pattern of use is likely to disappear as daily use begins. Nonetheless, not all heroin users become daily users, and some establish regular non-

dependent levels of recreational use.7, 57, 182, 179, 231, 232

In the majority of cases, regular, non-compulsive alcohol and cannabis use takes place in a social or recreational setting. These substances are usually perceived by those who use them to be aids to relaxation or communication or as a pleasant means to alter their mental atmosphere or attain a measure of euphoria. They may be used to relieve boredom or simply as a pleasant adjunct to other activities and appear to be a routine and normal part of the regular user's enjoyment of his leisure time.

Particularly in the early days of illicit LSD use, when the avowed sacramental and self-discovery qualities of the psychedelic experience were being publicized, consumption of this drug and similar hallucinogens was seen as a special event—not only for recreation but also for self-improvement and enlightenment. * However, as hallucinogen use has become more widespread, LSD, MDA and similar drugs are more often taken in recreational settings in a more casual manner, to enhance other social activities rather than as the raison d'etre of the gathering.

The use of alcohol as a 'social lubricant' is generally recognized and it is assumed by most people that the beverage is used, not solely for itself, but to stimulate social interaction and facilitate relaxation in a social context. Some groups of alcohol users, especially adolescents who are learning to use the substance, get together for the specific purpose of becoming intoxicated. However, as normative restraints develop and the consequences of excessive drinking are learned, there will be a higher likelihood that drinking will become secondary in the social context. Similarly, the 'pot party' where individuals gather specifically to become intoxicated may apply to some groups of new users, but as cannabis use becomes integrated into the life style of the user, it will usually become an adjunct to the ongoing social activity in the same way as recreational alcohol use is generally conceived to be.187 In any case, most non-medical drug use has its genesis in social groups, and continues to be a social and recreational phenomenon.

DEPENDENT DRUG USE

Once dependence on a drug is established, a pattern of daily—or more frequent—use, regardless of the social situation or the mental or physical condition of the user, will usually begin. Most people who use dependence-producing drugs know that others have lost control of their level of consumption, but few believe at the outset that it will happen to them. Becoming dependent on a drug is usually a gradual process throughout which an individual believes that he has control over his level-of-use while, in fact, the intervals between administrations of the drug become increasingly shorter. During the early stages of dependence, most users would claim that they could 'stop anytime'.

Tobacco dependence is probably the least traumatic as well as the most common form of drug dependence in Canada. Smoking is widely practised and tolerated and readily becomes associated with many events in the user's daily routine: with coffee, after dinner, in various social settings. Many tobacco smokers, in fact, may smoke on a daily basis for a protracted period of time without realizing that if use were discontinued withdrawal effects and craving would be experienced.33

Dependence on alcohol is usually slow to develop, and during the beginning stages of use the pre-alcoholic's drinking behaviour may be indistinguishable from that of his peers. However, Jellinek suggests that the pre-alcoholic may find the beverage to be more rewarding for tension release than do other drinkers.125 A typical pattern of becoming an alcoholic involves daily use at increasing dosages and perhaps, after a period of months or years of heavy use, the occurrence of blackouts. Sometime thereafter, morning drinking will begin, and the individual and those around him will become aware that he has lost control of his drinking behaviour. This process may take many years, although in some cases it may develop quite quickly, in response to a personal life crisis, for example.196

Although most 'problem drinkers' are involved in a daily use pattern at high-dose levels, there are several "species" or types of alcoholism.'25 One of these, which may be called "periodic alcoholism", entails occasional, but severe drinking bouts. These "habitual symptomatic excessive drinkers"163 may consume more alcohol over time than do daily drinkers, but they do not exhibit the same degree of loss of contro1.125 Such spree drinking may be just a stage in a career of alcoholism, but some individuals remain at this level and do not become daily dependent drinkers.

It seems, therefore, that not all patterns of use which involve a compulsive relationship between the user and his drug of choice require daily use over long periods of time. Patterns of daily as well as spree use of amphetamines have also been observed. One type of intravenous methamphetamine user encountered by Commission field workers maintained a relatively constant and very high daily consumption level."3 However, the more common `speed freak' pattern consisted of a series of continual 'runs' and 'crashes'. This latter pattern involved daily use at increasing dose levels for periods of a few days to a week. When use of the drug was terminated, a withdrawal phase characterized by physical exhaustion and extreme irritability and depression ensued. The most popular and common remedy for the unpleasant symptoms of this 'crash' was a new injection of amphetamine, and the 'run' would begin again.

Dependence on the opiate narcotics, particularly in their more potent forms, usually develops much more rapidly than dependence on alcohol. For those who eventually do become dependent, the period between first use and daily use of heroin usually varies from a few months to about a year.i17. 212 Dependent use is most often preceded by a period of social and recreational use. At some point, use becomes more frequent, both socially and in private, perhaps, in the latter case, to cope with stress or tension.204 Almost invariably, the user first becomes aware of his dependence when he experiences withdrawal symptoms and learns that they can be immediately relieved by the administration of an opiate.117, 151, 223

Sedative-hypnotic dependence usually results from medical prescriptions of these drugs. A general practitioner who does not fully appreciate the potential dangers of these drugs may provide his patient with a refillable prescription or the patient may go from doctor to doctor, complaining of the inability to sleep and, thereby, obtaining multiple prescriptions. Some alcoholics have been known to become dependent on sedatives. Barbiturates, purchased on the illicit market, are sometimes used by heroin dependents, and in later years, when their ability to support a heroin habit declines, some of these persons become dependent on these less expensive pharmaceutical substitutes.", 109 Although youthful multiple drug users are known to occasionally take sedative-hypnotics (particularly barbiturates and methaqualoncontaining substances), few cases of dependence in this population have come to the attention of the Commission. Should the use of these substances continue to diffuse, however, a pattern of youthful dependence on sedatives may emerge in the future.

PATTERNS OF MULTIPLE DRUG USE

In recent years there has been a growing social awareness of and concern about 'multiple drug use' or 'poly-drug use'. Although this pattern of drug use is sometimes seen as new and, perhaps, exotic, the consumption of a number of psychoactive substances is not a recent development or one confined to a specific segment of contemporary society. Broadly conceived, multiple drug users are those who ingest a number of psychoactive substances, either simultaneously or at different times. Accordingly, a person who uses alcohol, tobacco and caffeine is a multiple drug user, as are those who consume a variety of illicit substances apart from or in addition to these. Certain patterns of multiple drug use, however, are seen as more dangerous or more cause for concern than others, depending on the drugs involved, the levels and frequencies of use or their relative potential for harm.

In the literature of multiple drug use, the concept is often reserved for only those who use more than one illicit drug in a non-medical context. This can lead to certain conceptual ambiguities—where under-aged high school students use alcohol and tobacco, for example—in addition to imposing limitations on interpretations of the data and the cogency of the research results. A meaningful operational definition of multiple drug use should specify what drugs are under consideration as well as the context of use. For our purposes, we are interested in patterns of multiple use of any substances used in a non-medical context.

A second dimension which must be considered in arriving at a workable definition of multiple drug use is the frequency with which psychoactive substances are used and the dosages employed. Most multiple drug use studies employ a minimal definition: the multiple drug user is one who has 'ever used' more than one substance. Such a definition appears to be quite uninformative and unsatisfactory since individuals who have had little experience beyond the experimental stages of use are included with chronic, high-dose users (see Annex 1). Definitions of multiple drug use, therefore, should specify at what levels of regularity and frequency the substances in question are employed and, if possible, supply relevant dosage information.

Multiple drug use may be examined from two perspectives: as either concurrent or sequential patterns of use. In the former case, the emphasis is on the organization, patterning and interrelationships of the various substances in the life of the user at a particular time. The second perspective, that of sequential multiple drug use, involves the study of the temporal order in which each drug comes to be used or added to the pharmacological repertoire of the user. The concept of 'progression' is often subsumed under the general rubric of multiple drug use. However, sequential drug use may be distinguished from 'progression' insofar as the latter concept assumes that there is a hierarchy of drugs ranging from 'soft' to 'hard', weak to potent or less harmful to more dangerous, and that there is a tendency for drug users to move up this hierarchy to 'stronger' drugs. The emphasis of the term `sequential' is on the movement from one drug to another without necessarily implying increasing danger or movement to more potent substances, both of which are connoted by the word 'progression'.

CONCURRENT MULTIPLE DRUG USE

Patterns of concurrent multiple drug use may be distinguished as intermittent, simultaneous, cyclical or interchangeable.

When two or more drugs are used, but not at the same time, this pattern may be called intermittent multiple drug use. Thus, an individual may use cannabis and LSD, but not in the same situation. Intermittent multiple drug use often involves two quite different use patterns: the functional use of amphetamines, for example, may not overlap with the recreational use of other substances.

Simultaneous multiple drug use, on the other hand, may be defined as the ingestion of two or more psychoactive substances in such close conjunction that the effects of the drugs are acting on the organism at the same time. Some simultaneous patterns involve the deliberate consumption of two or more substances to obtain a specific interaction effect. An illustration of this is the `speedball', an intravenous combination of heroin and cocaine or methamphetamine. Others, however, may simultaneously use two or more drugs without being aware of their potential interactive or additive effects. For example, a daily user of a prescribed sedative-hypnotic may also use caffeine, alcohol or other drugs without taking into account his ingestion of the former.

When one drug is used as a substitute for another with similar psychopharmacological properties, interchangeable multiple drug use may occur. Thus heroin users may purchase barbiturates or, preferably, methadone when heroin is in short supply. Although they may find alcohol distasteful while using heroin, heroin users often drink to excess when abstinent from opiates 2b3 A number of interchangeable drug use patterns are further discussed in C. 4 Patterns of Use, "Social Theories of Multiple Drug Use".

Cyclical multiple drug use is the ingestion of two or more substances consecutively such that the later ones modify or counteract the terminal effects of the earlier ones. Those who have used alcohol to excess are familiar with the 'morning after' syndrome which often follows. 'Hangovers' are commonly treated by liberal amounts of caffeine, in the form of coffee, tea, or cola beverages. Codeine pills are sometimes used to relieve the accompanying aches and pain, and in some cases `wake-up pills' or amphetamines are used to counteract post-alcohol drowsiness.

Cycles of stimulation and sedation are a common multiple drug use pattern. 'Diet pills' or other stimulants are sometimes used to banish the `morning after' effects of sleeping pills. On the other hand, sedatives or alcohol may be used to induce relaxation or sleep after the effects of amphetamine begin to fade. 'Speed freaks' occasionally use barbiturates or heroin, if they are available, to self-medicate adverse withdrawal symptoms after a 'run' of high-dose, intravenous methamphetamine use. Commission research has confirmed that this form of cyclical multiple drug use has lead some speeders to a preference for heroin because of its capacity for stabilizing and tranquilizing without the adverse physical and psychological effects of the amphetamines.'"

Some of the recent concern over concurrent patterns of multiple drug use has been given impetus by what is called the 'garbage head syndrome'. In the spring of 1972, Commission field workers discovered that observers of the youth scene were becoming increasingly aware of this problem in cities across Canada.'" 'Garbage heads' have been described as the archtypal and extreme multiple drug users who consume a dazzling array of substances sequentially or in combination, with little regard to the consequences beyond `getting stoned'. With the recent lowering of the legal drinking age, much of this multiple drug use activity has been observed in pubs or taverns where large quantities of alcohol are used in combination with one or more other drugs. Often these young people will have little or no idea what drugs they have consumed, stating that someone offered them a pill of a certain colour and promised that it would get them 'stoned'.

Some observers believe that the 'garbage head' is likely to be a transitory or short-lived drug use pattern in most cases. When some adolescents begin to use alcohol, they go through a period of excessive use, drinking to the point of drunkenness and sickness. Eventually, most of these develop normative restraints and the ability to control their intake and their behaviour under the influence of alcohol. The 'garbage head syndrome' has been observed most frequently in provinces which have recently lowered the drinking age. It appears that whereas most high school aged drinkers and illicit drug users formerly experimented with these substances out of the public eye, they are now readily observable in drinking establishments. It seems reasonable to assume that, particularly after a number of unpleasant experiences, most `garbage heads' will exert some control over their drug intake and settle into more moderate regular or occasional patterns of consumption.

SEQUENTIAL MULTIPLE DRUG USE

Various 'progression' or 'stepping-stone' theories have been advanced to explain why individuals, having established the use of a particular drug, will experiment further with other psychotropic substances. In order to understand the genesis of these theories and how they came to have currency today, a brief historical introduction follows.

The Prohibitionists in the United States were the first to propose any kind of progression hypothesis:

The relation of tobacco, especially in the form of cigarettes, and alcohol and opiates is a very close one.... morphine is the legitimate consequence of tobacco. Cigarettes, drink and opium is the logical and regular series."'

Cannabis was not included as one of the drugs that was involved in this progression as it was not until the 1930s that consumption of marijuana became sufficiently widespread in the United States to receive public attention. The idea of the cannabis-heroin progression was first presented in 1931 by a Prohibitionist physician:

[Marijuana users easily] become engulfed in the abyss of drug addiction, and end their miserable existence either on the gallows, or in penal institutions and insane asylums. The moral and physical resistance to narcotics and alcohol is not only weakened but often destroyed in persons of stabilized personality, who are addicted, even to a moderate degree, to marijuana."

During the thirties and forties, the notion of the marijuana to heroin progression appeared in a few works on cannabis, but there was virtually no supporting evidence that such a relationship existed. Moreover, there was little consensus among these writers as to what factors 'caused' this alleged progression.158 At this time, those authorities most familiar with drug use—police officials and medical professionals—strongly denied that such an escalation existed.

After the Second World War, there appeared to be an epidemic increase in the extent of heroin use in the United States, particularly among young men of racial minority groups in large urban areas. The popular press suggested that this new heroin 'epidemic' and the 'new breed of addict' had come to opiate use through the use of marijuana. The assertions that cannabis was an extremely dangerous, addicting and crime-inducing substance were beginning to lose credibility at this time due to the findings of the La Guardia Commission and a number of psychiatric studies which appeared between 1944 and 1946.35, 55' 85, 181' 185 Some observers of the heroin scene came to the conclusion that cannabis use, per se, may not be as dangerous as they had thought originally, but that its use led to heroin and was thus responsible for the 'new breed' of user.

An examination of the social history of opiate use in North America reveals that the 'new addict' was, in fact, not a new phenomenon. The postwar users were seen to be quite different from the middle-class, middle-aged, medically dependent population of the turn of the century.256 However, the use of opiate narcotics by young delinquents was well established prior to the introduction and diffusion of cannabis. Although thousands of people who would otherwise be considered to be 'respectable' were dependent on patent medicines and home remedies containing opiates, there were also a number of 'underworld' denizens—gamblers, vagrants, and prostitutes—who were habituated to opium smoking or dependent on morphine. By the 1920s, when legal access to opiates had been restricted, a number of clinics were established in the United States to supply maintenance doses of opiates to those who were still dependent.15°, 234 One of the reasons why these clinics were eventually forced to close was the publicity given to the 'criminal element' in their patient populations.245 Apparently, dependence on opiate narcotics was quite common among the young, the socio-economically disadvantaged and the 'underworld' before the onset of widespread cannabis use.71, 136, 140, 250 There is good reason to believe that the post-war 'epidemic' was actually a reflection of a growing trend that had its roots in the changes which took place at or before the turn of the century and had only been interrupted temporarily by the war. The increase in heroin use in the late forties, according to this view, was due primarily to the re-establishment of overseas shipping and transportation routes, allowing once more for extensive illicit distribution of heroin.158

Once established in the late forties, concern about drug progression, specifically the escalation from cannabis to heroin, continued. However, with the diffusion of the use of LSD, barbiturates and amphetamines in the 1960s, the concept of 'progression' was broadened to take some of these substances into account, and thus the movement from cannabis to heroin is now often considered to be only one of a number of sequential drug use patterns.

Discussions of the relationship between cannabis use and the use of opiate narcotics may be found in Appendix A.2 Opiate Narcotics and Their Effects as well as in the Cannabis Report. In the latter document, the Commission majority acknowledge that certain individuals would engage in heavy multiple drug use whether they used cannabis or not, but asserted that,

... it is reasonable to assume that many would not engage in certain kinds of drug use if they did not use cannabis."

They concluded that, although cannabis use may play some role in influencing subsequent use of other drugs, sequential multiple drug use was too complex a process to assign a strict causal significance to one factor or one particular drug.

A number of retrospective studies of heroin users and follow-up studies of marijuana users are also discussed in the Cannabis Report and Appendix A.2 Opiate Narcotics and Their Effects of this report.9, 41, 54, 94, 199, 215

These studies have a number of methodological problems, the most important of which is their concentration on the most 'heroin-prone' populations, such that the results may not be generalized to the cannabis-using population as a whole. On this subject, Appendix A.2 concludes:

Specific pharmacological properties of marijuana (or any other drug) which might lead to a need or craving for other drugs have not been discovered. It would appear that dynamic and changing social and personal factors play the dominant role in the multi-drug-using patterns repOrted, and that the specific pharmacology of the compounds involved is secondary.

Historically, a number of varied, and often discrepant, theories have been proposed, all of which attempt to demonstrate that cannabis use is causally related to the subsequent use of other drugs. Although these explanations have differed radically in content as well as their level of sophistication, they will be presented, in the following pages, as a framework through which some understanding may be gained of the numerous mechanisms that may influence sequential drug use patterns or the movement from one drug to another.*

Psychopharmacological effects theories. The first and most classic type of explanation for the progression from marijuana to other drugs is the psychopharmacological effects model. Although these theories vary somewhat in their level of sophistication, the majority are naive and overly simplistic accounts of sequential drug use patterns. All of them single out the effects of cannabis as the determining cause of the progression.

One alleged effect of cannabis that was postulated to lead to heroin use was a loss of self-control or will power which was said to make the user more vulnerable to the use of other drugs.157 However, although a loss of self-control was alleged, no attempt was made to verify its existence.

Another explanation postulated a tolerance-disillusionment type of progression mechanism. It suggests that the initial 'kick' that marijuana users experience tends to wear off over time due to tolerance. The user then looks for a more powerful substitute. It has also been proposed that cannabis users expect ever-increasing pleasurable effects from the drug and are thus compelled to turn to stronger drugs to satisfy their "taste for drug intoxication"." This particular theory did not specify why it was only cannabis that could create a taste for intoxication rather than alcohol or other drugs used prior to cannabis. A variation of this general theme suggested that the cannabis user becomes psychologically dependent on the drug and that this paves the way for his subsequent use of heroin.'"

As we observed in the Cannabis Report, there has been no empirical verification of these theories, and no evidence that the effects of cannabis per se can be said to encourage later heroin-using behaviour.43 If the psychopharmacological effects of cannabis do in fact influence the user to turn to stronger drugs, we would expect a relatively constant rate of progression from marijuana to the use of heroin or other drugs.* However, there is no evidence to date which would suggest that all cannabis users—or even all cannabis users at a particular level-of-use—are equally likely to use other drugs in the future.29, 98,126

In addition, if one examines the processes by which people come to use heroin, it is difficult to single out cannabis use as a determining factor. There is no evidence to suggest that first use of heroin occurs when the individual has little power of resistance due to the direct effects of cannabis. Whether someone experiments with heroin or not depends on various aspects of his life style, his attitudes to the drug, as well as his past experience with heroin users. Finally, it is evident that the factors which influence first use or experimentation with heroin may be quite different from those which lead to opiate dependence (see Appendix D.2 Motivation and Other Factors Related to Opiate Narcotic Use).

Since cannabis is not a necessary precursor of heroin use (before 1965, few heroin users in Canada had taken cannabis prior to opiates),117. 194, 253 the most we may assume is that the effects of the drug could only be influential on certain cannabis-using persons, and that others find another path to heroin dependence. This type of thinking brought theorists to the point where they began to look at personality variables for the motivating forces leading people from cannabis to the use of other drugs.

Personality abnormality theories. The basic assumption of this kind of theory is that the majority of those who progress from the use of cannabis to the use of other drugs are, to varying degrees, psychologically disturbed. It is sometimes suggested that the use of cannabis is, in itself, indicative of an underlying personality problem and that those with more severe problems will not find cannabis to be a sufficient solution. They will, therefore, go on to heroin use (or the use of other drugs) in search of a more adequate problem-solving drug.

Psychological investigation of multiple drug users is usually conducted on those subjects whose patterns of drug use are assumed to be a cause for concern. Most observers, for example, would not consider daily use of alcohol, caffeine and tobacco to be indicative of an underlying personality disorder because of the legal status and general social acceptability of these drugs. Attention, therefore, has largely been focussed on chronic or high-dose drug users and those whose multiple drug use patterns include the use of

illegal substances.64, 113, 141, 168, 284

Although continuing to yield interesting data, psychological studies of multiple drug users do not provide us with precise information regarding the role of psychological variables in the choice of drugs in a drug-using career. Most of them are characterized by the same methodological problems as those studiec which have attempted to discover the psychological dynamics of heroin lependence, the 'addict personality', or the 'alcoholic personality'.38, 87 While some types of heavy multiple drug use would seem to indicate personality problems, many multiple drug users would clearly be diagnosed as psychologically normal. The relationships between psychological variables and the use of opiate narcotics, amphetamines and hallucinogens is further reviewed in Appendix D Motivation and Other Factors Related to Non-Medical Drug Use.

Social theories of multiple drug use. Although it is reasonable to hypothesize that increasing use of stronger drugs reflects the existence of severe personality disorders in some cases, other evidence suggests that factors in the social background and environment of the drug user may influence his particular sequential drug use pattern. Patterns of drug use reflect different meanings attached to drugs by different groups of individuals, and drug-taking behaviour is interwoven with other activities of group life.3 Orientation to and eventual selection of drugs, as seen from a sociological perspective, reflects a number of factors such as availability, information, and other influences in the immediate social environment.

With the use of one drug comes an increased likelihood of meeting others who use that drug and, perhaps, use other drugs, as well. That cannabis users are more likely than non-users to have drunk alcohol suggests that alcohol users have a greater chance of having friends who would be willing to offer cannabis to them. Similarly, the use of cannabis may introduce an individual to a wider range of persons who use a variety of legal and illegal drugs, and it has been hypothesized that this 'drug subculture' is a significant determinant of further drug use. However, the illicit 'drug subculture' is by no means a homogeneous entity and is better characterized as a mosaic of small `drug subcultures'. Multiple drug users may have in common the use of one or more illicit substances, but they differ in terms of patterns of multiple drug use and in their orientation and attitudes to specific kinds of drug use. A number of studies have confirmed that the choice of drugs which are to be included in the pharmacological repertoire of the drug user appears to be mediated by the immediate social and cultural environment.3, 29, 56, 126, 141, 195

Many of the same factors which help to determine regular drug use patterns also influence the numbers and kinds of drugs included in any variety of multiple drug use. As we have seen, availability of illicit substances plays an important role. Some degree of interchangeable multiple drug use is alleged to occur when an individual's current or favourite drug becomes unavailable or prohibitively expensive. The importance of this factor was emphasized by the R.C.M. Police in a brief submitted to the Commission:

... the scarcity of marihuana would act as a catalyst in introducing the drug user to stronger drugs which may be available, such as L.S.D., amphetamines, barbiturates and heroin....'

During the summer of 1969, a marijuana shortage was reported in the United States, and a study was undertaken to investigate its effects.'" Interchangeable multiple drug use patterns were reported by over three-quarters of one sample and by 84 per cent of another sample. The most common substitutes were alcohol and hallucinogenic drugs.

Some juveniles may use cannabis as a substitute for alcohol when it is more readily available to them in their immediate environment.3 It has also been suggested that volatile solvent users actually prefer alcohol as an intoxicant, but use solvents because they are too young to have ready access to alcoholic beverages.* It is evident, therefore, that sequential multiple drug use is sometimes encouraged by scarcity of the drug of choice and the substitution of a different intoxicant.