| - |

Drug Abuse

C Extent and Patterns of Use

C.3 CHARACTERISTICS OF USERS

A number of the difficulties with regard to providing information on the extent and patterns of drug use have been discussed in C.1 Introduction above. These difficulties, such as variations in the methodological sophistication of studies, the narrow scope of most studies and the choice of sample populations also apply to, and limit, the generalizability, validity and reliability of the available data concerning the characteristics of drug users. The most reliable and readily available socio-demographic data concerns the age, sex and socio-economic status of drug users. Therefore, these will be the variables emphasized in this section although other relevant factors will be discussed if valid and reliable data is available. As there are numerous studies of student drug users, but few good studies of adults who use illicit drugs, this discussion will, of necessity, focus mainly on young persons, primarily those in high school and university.

Discussions of survey data on social characteristics related to the use of drugs are predicated on the assumption that these relationships are not only statistically significant but socially meaningful. The assumption is that certain characteristics highly associated with the use of a drug have a predictive value in enabling us to determine which persons or groups are more likely to use that drug, at what levels-of-use, and with what patterns of consumption. Unfortunately, however, epidemiological concentration on specific populations (particularly high school and college students) and the fact that many survey findings refer only to that situation that prevailed at the beginning of the diffusion of hallucinogen use during the middle and late 1960s render any attempt to generally predict on the basis of social characteristics a speculative and often misleading exercise. Consequently, the following review of the social characteristics of Canadian drug users must be seen as a descriptive rather than analytical account, and reliable predictions must await the completion of more comprehensive and dichronic surveys.

OPIATE NARCOTICS

There is wide variability in the ages of heroin users in Canada, ranging from the late teens to over 60 years of age. Until the mid-sixties, most heroin users first became recognized by the Bureau of Dangerous Drugs (B.D.D.) between the ages of 25 and 39, indicating that this was the age range in which heroin users, on the average, were most likely to be first arrested for a narcotics or other offence or to appear for treatment. However, this was not usually the age range in which most users became dependent on heroin.253

An R.C.M. Police survey in Vancouver in 1945 indicated that over one-half of those arrested had started their heroin use at an average age of 17.4 while the overall average for the sample was 21.9.203 Dependence first occurred in the late teens or early twenties for over one-half of the samples of British Columbia heroin users who were studied by Henderson in the late sixties117 and by Stevenson and his associates253 in the mid-fifties. However, 21 per cent of Henderson's sample first experienced dependence before the age of 18, and most of the remainder became dependent by the age of 30. A recent Vancouver study by the Narcotics Addiction Foundation of British Columbia indicates that the younger patients who have come for methadone maintenance did not become dependent, on the average, until age 21.127 Although the age at which opiate users are recognized is declining (see C.2 Extent of Use, page 678), there is little evidence that people are using opiates or becoming dependent on opiates at significantly earlier age than did their counterparts in the past. Heroin use, in its beginnings, has been preponderantly a phenomenon of the late teens for several decades.

Patients who came to the Narcotic Addiction Foundation between 1956 and 1963 were questioned about the year they had first become dependent, and this was compared to their records at the Bureau of Dangerous Drugs. Fifty-one per cent had not been recorded by the B.D.D. after three years of regular heroin use. Twenty-eight per cent were still not known to the B.D.D. after five years of dependence."7 Thus, the national statistics at that time were not indicative of age of first dependence because there was a considerable timelag between dependence and becoming 'known' for a large proportion of the known habitual narcotics-using population.

In recent years, however, a growing proportion of new names have come to the B.D.D. from "retail reports" information (i.e., methadone prescriptions). Simultaneously, a greater proportion of persons under age 25 have come to their attention. It is increasingly evident that the timelag between first use of opiates and becoming 'known' is decreasing due to the apparent willingness of young users to apply for methadone maintenance at clinics or to appeal to private physicians for methadone prescriptions within their first year of heroin use.127 Furthermore, Commission research indicates that before the new restrictions on the prescribing of methadone came into effect in June 1972, a significant number of methadone prescriptions had been issued to persons who had had little or no experience with heroin. Thus, those who have used heroin may be recognized at an earlier age due to methadone prescriptions, and many young people obtaining methadone are possibly being listed as habitual narcotics users although they have had little or no previous involvement with opiate narcotics (see C.2 Extent of Use, page 678).

In addition, this increase in newly reported young users may be a result of changes in law enforcement practices. Recently more police emphasis has been placed on youthful drug users. The young are now more likely to be stopped and searched on the street and their residences are more likely to be investigated. Consequently, there is an increased likelihood that those who have used heroin for only a few months, some of whom may not be dependent on the drug, will be arrested for heroin offences.

Although the above-mentioned factors indicate that the drop in age of known heroin users in recent years may not reflect proportional changes in the using population, there is, nevertheless, evidence to indicate a small amount of heroin use among young teenagers. Halpern and Mori, for example, found that the proportion of Ottawa English-speaking students using 'opiates' (including heroin) in the two months preceding the survey was 1.1 per cent in grade eight, 3.3 per cent in grade ten, and 2.5 per cent in grade 12.1°8 The highest rates of use among Ottawa French-speaking students were found in grades nine (1.6 per cent) and 12 (1.7 per cent). Smart, Fejer and White found that 1.7 per cent of their 1972 Toronto grade seven sample claimed to have used heroin at least once in the six months preceding the survey; in grade nine use was 3.1 per cent; and both grades 11 and 13 had current use rates of 1.2 per cent.242 The Bureau of Dangerous Drugs' most recent tabulations of known habitual narcotics users include 50 persons (or 0.6 per cent of the 1972 total) under the age of 17.

Although the heroin-using population in the United States is disproportionately non-white, this is not the case in Canada. Heroin users here are predominantly white and Canadian born, although there are a few native Indians and a similarly small number of elderly Orientals.

The sex ratio of known users is approximately seven males to three females. However, among occasional users the sex ratio appears to be more balanced. Russell found a 3:2 male to female ratio among high school students in British Columbia in 1969 who had used heroin more than ten times,225 while a 1970 Vancouver study found the reverse ratio among the same category of users.18° However, when all students who had ever used heroin were considered, the male to female ratio was approximately 1:1 in both surveys. Smart, Fejer and White found a 3:2 male to female ratio among heroin users in their Toronto high school sample.242

Most dependent heroin users either marry or become involved in a commonlaw relationship with a member of the opposite sex sometime during their life time. Some have multiple liaisons. They tend to marry persons who are also involved in heroin use and many of these relationships take the form of a kind of business partnership as well as supplying love and companionship. Marriages are often interrupted and sometimes terminated by long prison sentences.

Most heroin dependents who have been studied in Canada and the United States have done poorly in school in spite of average or better intellectual potentia1.253, 263, 266 An analysis of Canadian heroin conviction statistics for the years 1967-1969 revealed that an average of 82 per cent of those whose grade level was stated had failed to reach beyond grade ten.'" In Henderson's British Columbia study, more than 80 per cent had left school by age sixteen.117 The reasons for leaving school were predominantly lack of motivation to continue, the desire to work and make money, or a reform school sentence.

Heroin users' difficulties in school carry over into their occupational adjustments, and only a minority have good work records. In a study of users in the United States, Vaillant found that not only dropouts from slum schools, but also many middle-class users had had employment difficulties prior to opiate dependence.263 Some have stated that they found their occupations to be uninteresting or not sufficiently remunerative, although some occupational problems may have been a result of juvenile or young adult criminal convictions and prison records.°5

One of the controversies surrounding the so-called 'criminal addict' is the extent to which his criminal behaviour is due to his drug use (in support of his habit) or existed prior to his introduction to heroin and was likely to have continued regardless. The extent of anti-social behaviour before dependence varies considerably with the population studied in the literature.'" The percentage known to be delinquent prior to heroin use ranges between 50 per cent and 75 per cent in most recent American studies.266 Two British Columbia studies suggest that the range is similar in Canada. Of the patients admitted to the Narcotic Addiction Foundation in the first six months of 1970, approximately one-half had had juvenile or adult convictions,127 whereas in an earlier study three-quarters had had such convictions prior to narcotics use.'" Henderson, in a third British Columbia study, found that although three-quarters of his subjects were to some extent involved in youthful delinquency, less than one-half committed repeated infractions which lead to arrest and conviction, and that these were not markedly different from those reported in juvenile crime statistics throughout the Western World.117 The study by Stevenson and associates found that about one-half of the British Columbia female dependents studied had engaged in prostitution prior to their use of heroin.253

Heroin consumption and trafficking is usually centred in dilapidated and overcrowded urban neighbourhoods in North America. This does not, however, mean that those who eventually become dependent on heroin are necessarily from lower-class families. Over three-quarters of those that Stevenson and his associates studied in Oakalla prison near Vancouver, had come from homes that were financially comfortable or at least marginally so, with an income sufficient to cover actual needs of the family. Only a minority of the subjects came from backgrounds of actual poverty.253 Over forty per cent of the subjects in another British Columbia study had come from homes where the father or father substitute was a professional, a white-collar worker or a skilled labourer. Five per cent of the fathers had been unemployed or engaged in unlawful pursuits, but otherwise the occupational distribution was about the same as the population at large.117. 167

In studies of opiate dependents conducted in Canada and the United States in recent years there appears to be a higher incidence than in the general population of families which had been disrupted by death, desertion, separation or divorce.", 117, 253, 266 Many homes, however, were discovered to have been intact, stable and comfortable. Those who eventually become dependent on heroin tend to leave the family early, but this is undoubtedly due in some measure to their premature departure from the school system, and, in some cases, juvenile arrest and subsequent reform school terms.

Although much has been made of unhappy childhood experiences and the resultant personality problems which have been hypothesized to be related to opiate dependence, it has become evident in recent years that heroin users are not, for the most part, suffering from a crippling mental illness.266 They have been said to be maladjusted, depressed, hostile, immature, manipulative, narcissistic, and to suffer from feelings of inadequacy. However, virtually nothing is known about these individuals prior to opiate dependence and it is difficult to determine if these diagnosed characteristics were present prior to the use of heroin or are a result of the life experience and stigmatization of the individual after dependence occurs.162

The studies involving psychiatric diagnoses are usually without an adequate control group and are most often conducted in an institutional setting where the individual is often being held involuntarily, stripped of his identity supports and compelled to make an adjustment to a foreign environment.23 In a study of prisoners in Oakalla Prison Farm, those who had used heroin were no more likely to be transferred to the Provincial Mental Hospital than prisoners without heroin experience.253 The conclusion of the Stevenson study was that "addicts are basically ordinary people", characterized by an absence of healthy resources rather than by the presence of demonstrable pathology. The relationship between opiate dependence and psychological problems is discussed in more detail in Appendix D.2 Motivation and Other Factors Related to Opiate Narcotic Use.

AMPHETAMINES AND AMPHETAMINE-LIKE DRUGS

Canadian intravenous amphetamine users tend to be in their late teens or early twenties. The age range of 218 speed users studied in Toronto in 1970 extended from 13 to 30, with the average age for both males and females being approximately 17.148 Occasionally 'speeders' as young as 12 or 13 have been encountered, and it appears that the mean age may have declined slightly over the past few years as speed use diffused into the suburbs and urban high schools of some regions.

There are usually two or three males to every female in a speed community, although the sex ratio may be a nearly balanced one if all speed users (including those who live with their parents) are considered."3, 237

While some of the first members of North American speed-using communities were college educated, this is generally atypical in Canada.179, 1" In a Toronto study, most speeders who did not reside with their parents had left high school before graduating, and between 60 and 70 per cent of the total speed-using sample had failed at least one grade.'" Commission-supported field studies in Montreal and Toronto collected relatively similar data regarding academic performance and levels of achievement.16°. 188 Furthermore, only a small minority of intravenous amphetamine users are employed on a regular, full-time basis.148 Some, of course, are students (up to one-third of the Halifax speed-using population in 1971, for example245) but among those involved in the 'street scene' there is little desire to work, poor occupational training and, very often, a paucity of legitimate opportunities. Those who do work are engaged primarily in blue-collar employment245 and the occupational histories of unemployed speeders usually consist of multiple short-term jobs of an unskilled or semi-skilled nature such as sign-painting, taxi-driving, construction labouring, go-go dancing, and restaurant kitchen work. It should be indicated, however, that working speed users are less likely to actively participate in a street scene and, therefore, were less likely to come under Commission observation.

Several studies of speed-using populations have confirmed the middle and upper-middle class origins of the majority of their members.148, 195, 217, 248 It is probably important to note, however, that residents of Toronto 'speed houses' in 1970 were likely to come from lower-middle and upper-lower class families whereas visiting, purchasing, or transient speeders were more likely to have parents of higher social strata.188 Commission field researchers found that street speeders described their familial relationships as unsatisfactory and generally expressed negative or hostile attitudes towards their parents. This same research, and another study in Toronto, found that a disproportionately high number of these individuals come from broken or foster homes.148, 188 More than one-half of a speed group studied in Toronto had seen a psychiatrist at least once prior to their use of amphetamines."

Although information about the social characteristics of speed freaks is somewhat impressionistic, the pattern of use—chronic, high-dose, intravenous—is fairly clearly defined. The survey data on oral amphetamine use, although perhaps obtained in a more rigorous manner, suffer from another problem: the lack of a clear definition of the type of use involved. Few recent surveys, with the exception of Commission-sponsored research, distinguish between prescription and non-prescription use. The data from surveys which do not draw this distinction should be interpreted with caution.

Commission studies found that in the case of high school students, the medical (i.e., drugs obtained by prescription) use of 'diet' and 'pep pills' was uncommon among those under the age of 15, and that the incidence of such use was relatively constant between ages 15 to 19. Medical use among those in university had its highest rate among those over 30 years of age, while non-medical use was most often found among those between 25 and 29. Fejer and Smart found that among adult drug users in Toronto, 'stimulant' use was most prevalent in the age group 18 to 25. (Data was not presented for those under 18.) The authors state that:

There was no significant difference in age and the duration of stimulant use or in the number of tablets taken in a 24 hour period. However, more stimulant users age 18 to 25 obtained stimulants without a prescription than in the older age groups. About 55% of stimulant users 18 to 25 did not receive their stimulants on prescription compared to 23.5% of those 26 to 45 and none of those over 45."

In the late sixties, the sex distribution of high school stimulant users in Montreal, Toronto and Halifax was about one and one-half males for every female.272 In Toronto high schools in 1970 and 1972, the sex ratio of those who used stimulants within the previous six months was about 1:1, with females constituting a very slight majority of the users.242 The Commission's study of a national sample of Canadian adults found that more than twice as many females (17 per cent) as males (8 per cent) had ever used 'diet' or "pep pills" "under a doctor's supervision", while about the same proportion of men and women had used them without such medical supervision.

Fejer and Smart, however, found that there was no significant difference between the proportion of Toronto male and female adult stimulant users, and while females were more frequent users than men, they had generally been taking stimulants for a shorter period of time.82 They also found that while more than three-quarters of the females using stimulants received their drug through a doctor's prescription, only one-quarter of the men did so.

The Addiction Research Foundation of Ontario studies of 1968 and 1970 found that the use of 'stimulants' was most prevalent among high school students whose fathers held professional or managerial positions.241 However, in their 1972 study, "no father" and "father not working" categories were added.242 This changed the findings significantly as it was found that stimulant use was highest among those students who had no father, When those with no father and non-working fathers were excluded, a pattern similar to that of the 1968 and 1970 studies emerged. Commission surveys indicated that the non-medical use of 'diet' and 'pep pills' was not clearly or consistently related to personal income or to parental occupation or income. However, the Commission's national adult survey indicates that higher than average rates of 'diet pill' use occurred among persons employed in clerical and sales jobs and service and transportation industries, and among those not in the labour force. The incidence of 'pep pill' use, as reported in the same survey, was higher than the national average among professionals, managers and clerical and sales personnel.

HALLUCINOGENS

People from diverse segments of the North American population have experimented with hallucinogenic substances. The use of LSD and similar hallucinogens began in groups of highly educated persons who were largely from upper socio-economic levels and who experimented with these drugs in medical or quasi-medical settings. As information about these substances spread, a black market gradually arose to serve the needs of those whose curiosity had been aroused, and the non-medical use of hallucinogens diffused, thereafter, through every stratum of society.

The average age of initiation to non-medical LSD use has dropped steadily in the last 15 years. Disturbed children have had LSD therapy in hospital16 and cases have been recorded of young parents giving psychedelics to their pre-teen children.26 Cases have also been reported of accidental ingestion by children as young as one year old.259 However, voluntary initiation into nonmedical hallucinogen use presently occurs most frequently during the mid-or late teens, and use is concentrated among adolescents and young adults.

Smart, Fejer and White found a strong inverse correlation between hallucinogen use and grade average among Toronto high school students between 1968 and 1972.242 In their 1972 study they found that of those students having an average of 50 per cent or less, 16.3 per cent used LSD, while only 2.8 per cent of those with an average over 74 per cent claimed to use this drug. Whitehead, in his review of several Canadian high school studies, reported a similar pattern.272

In its beginnings, the 'hippie movement' appeared to be a middle-class phenomenon, primarily involving the sons and daughters of the nouvelle bourgoisie. Indeed, those who were in the vanguard of the 'love generation' had come primarily from the white middle classes of the United States, although there were a few blacks on the pheriphery of the movement.2" Although the first LSD users were middle class, as early as 1966 it became apparent that LSD was being taken by young people in 'ghetto' areas of New York City262 and that the urban 'hippie' communities attracted young people from all levels of society.

Smart, Fejer and White and Whitehead found a strong relationship in 1970 between father's occupation and the use of LSD and other hallucinogens.241. 272 The use of these drugs was highest among the children of fathers who were professionals and managers. In a replicatory study conducted in Toronto in 1972, Smart, Fejer and White found that no significant relationship existed between father's occupation and the use of LSD or other hallucinogens.242 The addition of two new 'father's occupation' categories in the 1972 survey may, however, have been responsible for this finding and, therefore, brings into question the previous correlation.

It appears that in the late 1960s there were many more male than female high school students using LSD and other hallucinogens, although all studies do not confirm this. In one sample, Russell, found an almost 1:1 sex ratio among LSD-using high school students in British Columbia in 1969.225 Whitehead, on the other hand, found an almost 2:1 male to female sex ratio for LSD users and close to a 4:1 male to female ratio among other hallucinogen users in the same year.272 Smart, Fejer and White found that the male to female ratio for the use of LSD and other hallucinogens among Toronto high school students was greatly equalized between 1968 and 1972.242 In 1968, 5.6 per cent of the male students and 1.3 per cent of the female students used LSD, while in 1972 the rates of use were 7.1 per cent and 5.6 per cent for males and females respectively. However, this difference was still statistically significant. The male to female ratio for the use of other hallucinogens dropped from approximately 2:1 in 1968 to a statistically nonsignificant ratio of about 7:6 in 1972. Commission survey data gathered in 1970 indicates that the male to female ratio of hallucinogen users was about 3:2 in high schools, colleges and universities, and 2:1 among Canadian adults.

ALCOHOL

As most of the Canadian epidemiological studies concerned with alcohol consumption have sampled either high school students or adults, the data presented here will focus primarily on these two populations.

Data from a number of high school surveys show that older students (those in higher grades) are more likely to use alcohol than younger students.108, 242, 243 Social class and academic performance do not appear to be significantly related to use of alcohol among high school students. Male students, however, generally display higher rates of alcohol use than their female counterparts.241, 242, 272

There are very few Canadian studies that provide reliable information on the social characteristics of alcohol users. One of these is a 1969 Addiction Research Foundation of Ontario survey of Ontario residents 15 years of age and over.75 This study found alcohol use was most common among persons between the ages of 20 and 49 (about 90 per cent of this age category), and that the incidence of alcohol use declined relatively consistently in all age categories beyond 50 years of age. This same study reported that while 86 per cent of Ontario males used alcohol, only 75 per cent of the females did so. Alcohol use and income-level were found to be directly related, with the incidence of use rising from 60 per cent of those earning under $5,000 per year to 90 per cent of those earning over $15,000 per year,

A 1961 Addiction Research Foundation study of the alcoholic population, (`problem drinkers', 'alcohol addicts' and 'chronic alcoholics') in Frontenac County in eastern Ontario, indicates that 16 per cent of this population were women and 84 per cent were men. Seventy-one per cent of these alcoholics were between the ages of 30 and 59, and three occupational categories accounted for over one-half of the alcoholic population: "service and recreation", "craftsmen and production workers", and "unskilled labourers" (other than those included in other occupational classes).1 However, the methodological problems involved in the detection of alcoholic populations—particularly women—limit the reliability of these findings.

BARBITURATES, MINOR TRANQUILIZERS AND OTHER SEDATIVE-HYPNOTICS

The Commission's national adult survey indicates that there are proportionately about twice as many adult females as males using tranquilizers under a doctor's supervision, and that for every two adult males using 'sedatives' under medical supervision there are about three females. Fejer and Smart found a similar adult male to female ratio for use of tranquilizers, but they found no significant difference between the proportions of male and female barbiturate users.82 The fact that females are more likely to use these substances has been noted in the United States, and by other researchers in Canada as wel1.52, 67, 171• 191, 236

The Commission adult survey also found that the use of tranquilizers was highest among adults under 30 years of age and among those 60 years of age and over. However, Fejer and Smart, in a 1971 random sample of Toronto adults (aged 18 and over), found no significant difference in age between users and non-users of tranquilizers, although they do report a significant age difference between users and non-users of barbiturates.82 The highest incidence of use was found among those between 36 and 50 and those over 60 years of age.

Fejer and Smart also found that adult tranquilizer users and non-users did not differ significantly in marital status, birth place, educational background and occupation.82 Barbiturate use, however, occurred significantly more often among persons who were remarried, divorced or widowed than among those who were single, and barbiturate users had a significantly higher level of educational attainment than non-users. No significant difference between users and non-users of barbiturates was found with regard to occupation or birth place.

The Commission's survey of Canadian adults indicates that persons who use tranquilizers are most often employed in clerical, sales or professional and managerial cccupations. Persons not in the labour force, including housewives, show an even higher rate of tranquilizer use than members of these occupational categories. These findings would seem to corroborate the generally accepted hypothesis that tranquilizer use is predominantly a middle-class phenomenon.

Barbiturates, tranquilizers and non-barbiturate sedative-hypnotics are used both medically and non-medically by high school and university students in North America. The Commission surveys indicate that Canadian college and university students have about twice as high a rate of tranquilizer use as high school students: about eight per cent of Canadian high school students at some time used tranquilizers obtained by prescription, and an additional three per cent claimed to use them without benefit of prescription; 14 per cent of college and university students had at some time used tranquilizers on prescription, and an additional five per cent had used them without any prescription. A large number of studies indicate that the use of tranquilizers is more prevalent among female than male high school students.25, 81, 139, 180, 225, 240, 242, 251 The Commission surveys found this trend to be true for both medical and non-medical use of tranquilizers in both high school and college and university populations.

Whitehead, in a 1969 study of Halifax high school students, found that the highest proportion of barbiturate and tranquilizer users came from homes where the father or "male guardian" was a professional or manager,272 while Smart, Fejer and White, in a 1970 study of Toronto high schools, found that the highest proportions of students who used these drugs came from families where the father was employed as a professional or a skilled worker.241 However, a 1972 Toronto survey found that the incidence of barbiturate use was highest among those high school students reporting "no father" and "father not working".2'2 These occupational categories were not provided in the 1970 survey. Several surveys have discovered that there are much higher rates of student barbiturate and tranquilizer use if the parents of high school students, particularly the mothers, also used these substances or other psychotropic drugs.240, 241

Smart, Fejer and White and Whitehead found that the greatest proportion of high school barbiturate and tranquilizer users were found among those who had a grade average of under 40 per cent, that this was consistent over time (1968 to 1972), and that there was a statistically significant inverse relationship between grade average and the probability of barbiturate and tranquilizer use.242, 272 For example, Whitehead, in his 1969 study of Halifax high schools, found that 17 per cent of those students with an academic average of under 40 per cent had used barbiturates in the past six months while only two per cent of those with an academic average of 75 per cent or more had done S0.272

VOLATILE SUBSTANCES: SOLVENTS AND GASES

There are several differentiable classes of individuals using solvents in North America today. Adult use is rare, but not unheard of. Some housewives, for example, have been known to sniff nailpolish remover. The most common illustration of adult use of solvents, however, involves persons whose institutionalization (in jails or psychiatric hospitals, for example) deprives them of access to alcohol. It has been reported that they would gladly give up their use of solvents and drink alcohol if given a choice between the two.202

There is some use of solvents, chiefly gasoline, in rural areas.68. 86 This activity usually takes place among young boys, and is much less common among adults. Gasoline sniffing is usually performed alone in these areas, a pattern differing from that seen in urban settings where a group situation is often the rule."

Another group of solvent sniffers, and the one given the most publicity, involves pre- and young adolescents. Most American studies deal with lower-class children, who use solvents in 'gang' settings. Less information is available on children and adolescents of other social classes or the solitary sniffer. It appears that the emphasis on lower-class group use is because, "it is in [lower class] neighborhoods that cases come to the attention of police, school officials, etc., with resultant mass media publicity."1 i8 It should be emphasized, however, that the low visibility of middle-class solvent consumption does not necessarily indicate a lower incidence of use within this population.

Adolescents who are part of lower-class solvent-using groups are often from disorganized families.2, 3, 11, 12, 29, 37, 138, 153, 202, 222 Only a minority are reported to live with both of their parents,222 a third are said to have an alcoholic parent,12 and many are from large families, almost half of one sample having at least four brothers or sisters.37 These individuals often do poorly at school and are frequently truant.11, 222 They average one academic year behind their contemporaries.'"

By the mid-1960s, Canadian solvent use became visible among middle-class pre-adolescents and young teenagers. Gellman reports that solvent sniffing was first noticed in Winnipeg in 1964 when teenagers began purchasing nail polish remover in quantity.86 These youths were far from secretive about the purpose of their purchases and, in 1966, some Winnipeg high school principals estimated that up to five per cent of their students were using solvents." Most of these student sniffers were not economically deprived but, rather, were from middle-income families. Canadian surveys of solvent users, unlike most of the studies conducted in the United States, have not restricted their focus to lower-class youth and, in general, have found that use of these substances is not particularly associated with the lower-classes. In fact, many studies found there to be no relationship between social class and solvent use.si, 240, 241, 272

Studies of solvent use indicate that such use in Canada is almost exclusively confined to young persons. However, adults are rarely surveyed as to their use of solvents and would, in any case, probably not admit to such an indulgence. From the information available, it appears that, in general, solvent users range in age from about 10 to 14, and that there is very little sniffing among university students and the general adult population. Rubin in a review of American studies conducted in the mid-1960s, found that the average ages of sniffers was reported to vary from a low of 11.9 years to a high of 14.8 years.221 Unfortunately, studies of elementary school children under ten years of age have not been conducted and therefore it is impossible to determine the proportion of children under ten that use these drugs.

Rubin, in his review of American studies, indicates that the ratio of males to females in youthful solvent-using samples ranged between 22:1 and 5:1.22' Recent studies of Canadian public and high school students have found a much more even distribution between male and female solvent users. In the late 1960's, there were slightly more males using solvents than females,226, 272 while in 1972, at least in Toronto, this situation seems to have been reversed.242

Canadian solvent users do not do as well in school as their peers, are more likely than non-users to be from broken families or families where the father does not work, and they are more likely to have parents who use psychotropic substances.240, 241, 242, 272

TOBACCO

Department of National Health and Welfare statistics for the years 1964 to 1970 indicate that between seven and eight per cent of Canadian males aged fifteen years and over "smoke pipe and/or cigars" exclusively. These figures also indicate that less than 3.5 per cent of Canadians smoke cigarettes at a level-of-use of less than once per day.44 As about 80 per cent of Canadian tobacco users smoke cigarettes and do so at least once per day, the following discussion shall deal primarily with this population of "regular cigarette smokers".

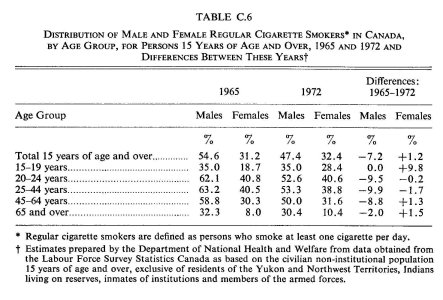

As indicated in Table C.6, the proportion of teen-age males who smoke cigarettes regularly has remained fairly stable between 1965 and 1972, while there has been a substantial decrease (on the order of 15 per cent) in the proportion of Canadian males aged 20 to 64 years who smoke cigarettes. The greatest increase in the proportion of persons who smoke on a regular basis occurred among teen-age girls. In 1965, 18.8 per cent of the girls 15 to 19 years of age smoked at least one cigarette per day, while in 1972 28.5 per cent did so. This represents a 52 per cent increase in the proportion of regular smokers in this age group. However, most teen-age girls smoke less than 26 cigarettes per day, and the majority in each year from 1965 to 1972 smoked less than 11. This increase in the proportion of female teenage regular smokers does not necessarily mean that there will be a substantial rise in the proportion of women cigarette smokers in the future as it may be due, at least in part, to increased female willingness to admit to smoking and to women starting to smoke at an earlier stage. There was little change in the proportion of female regular smokers in other age groups. Health and Welfare statistics indicate that about 40 per cent of Canadian women aged 20 to 44 years smoke regularly, while about 32 per cent of those between 45 and 64 years of age do so.65

There are some noteworthy regional variations in the proportion of Canadians who smoke one or more cigarettes per day (i.e., regular smokers). In 1970 (the latest year for which relevant data was available to the Commission), about 41 per cent of the Canadian population 15 years of age and over smoked cigarettes regularly. The incidence of use in the Atlantic provinces was the same as the national figure, while 47 per cent of the Quebec population smoked regularly. The proportion of regular smokers in Ontario, the Prairies and British Columbia was about 38 per cent.66

The regional pattern for male regular smokers was similar to the above distribution. Forty-nine per cent of the national population smoked regularly. The proportion of male regular smokers in the Atlantic region (51 per cent) was slightly higher than the national figure while, in the three western regions, the rate was lower, about 44 per cent. The highest rate of regular use among males in 1970 occurred in Quebec (59 per cent). There were fewer regional variations in the distribution of female regular smokers. Apart from Quebec, where approximately 36 per cent of the female population over 14 years of age smoked regularly, the national and regional incidence of regular cigarette smoking ranged from 31 to 33 per cent.66