| - |

Drug Abuse

B.9 TOBACCO

LEGAL SOURCES AND LEGAL DISTRIBUTION

During the 19th century, Ontario developed as the principal tobacco-growing area of Canada, a trend that has continued to the present. Ontario now produces over 90 per cent of the tobacco grown in Canada, including significant export quantities. Although tobacco was grown in Quebec at an earlier date than in Ontario, it presently accounts for less than seven per cent of the total national production. Likewise, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick produce a small amount; only experimental tobacco crops have been planted west of Ontario.

Canada is fifth in the world in the production of flue-cured tobacco. Total annual 1970 Canadian production of all types0of tobacco was estimated to be approximately 222 million pounds, green weight, an estimated 214 million pounds of which were flue-cured. This represented a total estimated farm value of $142.9 million 10

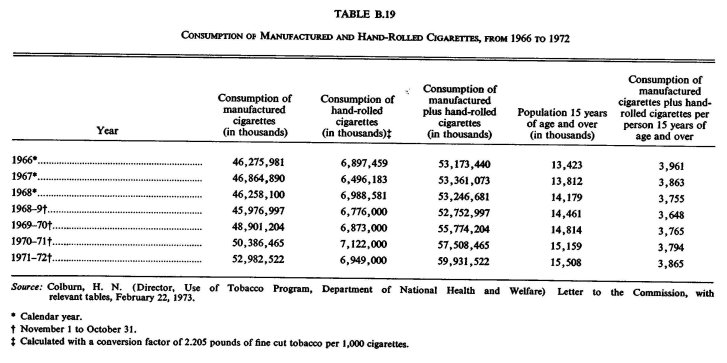

Tobacco is second only to wheat in Canadian agricultural exports.° Flue-cured tobacco exports in 1971 were estimated to be 48 5 million pounds, valued at somewhat more than $53 million. Eighty-five per cent of this tobacco was exported to the United Kingdom.° Only about two per cent of all tobacco consumed in Canada is imported.2 As can be seen from Table B.19, Canadians consume a substantial number of cigarettes. It is of some interest to note that the per capita consumption of cigarettes by Canadians 15 years of age and over decreased between 1966 and 1969; however, the per capita rate of cigarette consumption had returned to the 1967 level by 1972." For further information on the epidemiology of tobacco use in Canada, see Appendix C.2 Extent of Use, "Tobacco".

The cultivation of tobacco is a significant source of income and employment in Canada. In 1970, the total estimated capital investment in tobacco farms in Canada was $436 million. About 9,500 full-time and 40,000 seasonal workers are employed in the cultivation and harvesting of this product.8 The manufacturing and processing of tobacco products involve an additional 1,500 employees with a total payroll of about $60 million Purchases of materials by manufacturers, excluding tobacco, run to about $40 million annually and, in 1967, their advertising budgets approached $15 million. In addition, the number of share holders in tobacco manufacturing firms is in excess of 17,500.8

The industry also reflects significant economic activity at the wholesale and retail levels. Tobacco products are distributed through some 90,000 retail outlets and 650 wholesale and distribution enterprises.8 In 1969 the combined wholesale and retail annual income of the tobacco industry was estimated to be about $180 million.8

The greatest financial benefits of the tobacco industry accrue, however, to the federal and provincial governments. In 1971 total Federal Government revenue from excise taxes and sales taxes collected on tobacco products totalled $620 million.15 In 1968 federal tobacco taxes accounted for about six per cent of total Federal Government revenues.8 The provinces, in 1971, collected about $215 million in tobacco taxes, and tobacco manufacturers paid an additional $29 million in corporate taxes.15 In all, federal and provincial taxes account for more than 60 per cent of the retail price of tobacco products in Canada.8

The distribution of tobacco products is controlled by both federal and provincial government statutes and regulations. At the federal level, the Excise Act determines the tax that must be paid by the manufacturer. This system of tax collection is implemented through a stringently-controlled series of measures, including licensing and bonding of the manufacturer, monthly returns regarding his sales and purchases, annual reporting of his equipment inventory, and a requirement to make available to government inspectors, when requested, company books, accounts and papers.

Another federal statute, the Tobacco Restraint Act, regulates some aspects of the distribution of tobacco products. It prohibits the sale or giving of any tobacco product, or cigarette papers, to anyone under the age of 16 years. This prohibition carries with it a sanction in the form of fines of up to $10 for a first offence, up to $25 for a second offence and up to $100 for a third or subsequent offence. This Act also prohibits persons under the age of 16 years from purchasing tobacco, having it in their possession, or smoking or chewing tobacco in a street or public place. The maximum fine for a third or subsequent offence is four dollars. This statute also prohibits keepers of cigarette vending machines from permitting their use by persons under 16 years of age.

All the provinces of Canada levy a cigarette tax which, in every case, must be collected by the retailer from the customer. While taxation levels vary from province to province, a number of administrative devices are common to all the provinces. For example, all retail vendors of tobacco products must receive a license from the provincial government; and the onus is on the retailer to ensure that, regardless of the price at which the product is sold, the full tax is paid to the province.

Each province also has legislation governing the minimum age of persons to whom tobacco products may be sold. In most respects, the provincial statutes resemble the federal Tobacco Restraint Act, although most provinces make an exception in the case of a child who is obtaining a tobacco product on behalf of a parent, guardian or, in some cases, an employer.

Because tobacco products—unlike alcohol—are not distributed under government monopoly, there are few limitations, other than those listed above, on the manner in which they may be distributed. However, as of January 1, 1972, the Canadian Tobacco Manufacturers Council (composed of four major cigarette manufacturing companies) committed its members to a 'Cigarette Advertising Code' governing the advertising of all cigarettes.12 This Cigarette Advertising Code contains a number of voluntary restraints on cigarette advertising, including the following provisions: that member companies shall not advertise cigarettes on television or radio after December 31, 1971, and shall limit advertising expenditures in remaining media to 1971 levels; that cigarette packages produced after April 1, 1972 shall bear a warning that the Department of National Health and Welfare advises that danger to health increases with the amount smoked; that cigarette promotions involving incentive programs offering to the consumer cash or other prizes shall be discontinued; that the average tar and nicotine content of cigarette smoke shall not exceed 22 milligrams of tar, moisture-free weight, and 1.6 milligrams of nicotine per cigarette; and that cigarette advertising shall be addressed to the adult population of Canada, with a concomitant ban on cigarette promotions in the immediate vicinity of primary or secondary schools.

LEGAL SOURCES AND ILLEGAL DISTRIBUTION

Since the cultivation of tobacco is not prohibited in Canada, there are technically no illegal sources of this drug. All illegal tobacco distribution that does occur involves customs or excise violations, theft, and the possession by or sale to minors of tobacco products.

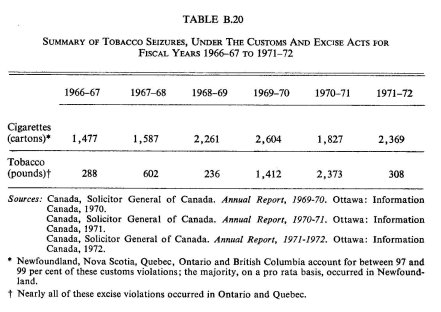

The smuggling and bootlegging of tobacco does not appear to be a major problem in Canada. There is some evidence that cigarettes are regularly smuggled into Newfoundland from the duty-free port of Saint Pierre, where they sell for two dollars a carton.19 However, according to a recent Annual Report of the Solicitor General of Canada, this type of commercial venture is atypical as "the majority of [customs] seizures were of items illegally brought into Canada for personal use".5 While it is impossible to estimate the total amount of such smuggling and bootlegging (or the consequent loss in federal and provincial tax revenues), Table B.20, which reports the extent of tobacco seizures between the fiscal years 1966-67 and 1971-72, indicates the widespread nature of this phenomenon.

The theft of tobacco products at the wholesale level has also been occasionally reported.", 18 Unfortunately, however, Canadian criminal statistics do not permit the identification of arrests or convictions solely related to tobacco thefts, so the extent of such activity cannot be ascertained at this time.

Since federal and provincial laws regulating the possession and sale of tobacco products are primarily directed at juveniles (see B.9 Tobacco, "Legal Sources and Legal Distribution", above), the chief offenders of these laws are persons under 16 years of age and those who sell to them. These laws, however, are very infrequently enforced. An examination of the Annual Police Reports of the major cities in Canada for 1969 reveals that only one city, Ottawa, reports a breach of the Tobacco Restraint Act—and that single arrest occurred in 1966.17 In 1968 only three juveniles in all of Canada appeared before a court for smoking and buying cigarettes, and all three cases were adjourned sine die.7

Even casual observation, however, indicates that minors smoke openly in every Canadian community. While there are no studies extant of how these youths obtain tobacco, the retailing of cigarettes, is such that anyone with the correct change and the requisite skill can easily obtain them from unattended vending machines. Juveniles can also purchase cigarettes, by the pack or single cigarettes, from many corner stores, or can arrange for older friends or relatives to buy tobacco products for them. Cigarettes, of course, can also be easily stolen (since few persons keep track of the number of cigarettes in their possession at any given time), or they may be freshly rolled from 'butts' collected in various public places. The laws restricting tobacco possession and use to those 16 years of age and over appear to be generally unenforceable.

References

1. Tobacco Restraint Act, R.S.C. 1970, c. T-9.

2. Canada, Department of Agriculture. Statistics on Canadian tobacco. The Lighter, 1971, 41(1): 26-27.

3. Canada, Department of National Health and Welfare. Trends in cigarette consumption, Canada 1920-1970. Unpublished manuscript, Canadian Smoking and Health Program, Ottawa, 1970.

4. Canada, Department of the Solicitor General. Annual report, 1969-70. Ottawa: Information Canada, 1970.

5. Canada, Department of the Solicitor General. Annual report, 1970-71. Ottawa: Information Canada, 1971.

6. Canada, Department of the Solicitor General. Annual report, 1971-72. Ottawa: Information Canada, 1972.

7. Canada, Dominion Bureau of Statistics. Juvenile delinquents, 1968. Ottawa: Queen's Printer, 1970.

8. Canada, House of Commons. Report of the Standing Committee on Health, Welfare and Social Affairs on tobacco and cigarette smoking. Ottawa: Queen's Printer, 1969.

9. Canada, Statistics Canada. Exports by commodities: December 1971. Ottawa: Information Canada, 1972.

10. Canada, Statistics Canada. Tobacco and tobacco products statistics quarterly: March 1972. Ottawa: Information Canada, 1972.

11. Canadian Press. Cigarette thieves bore through concrete wall. Montreal Star, November 22, 1971.

12. Canadian Tobacco Manufacturers Council. Cigarette advertising code of the Canadian Tobacco Manufacturers Council. Unpublished manuscript, n.p., 1972.

13. Charlton, L. Bootleg cigarettes: A hot business. Chronicle-Herald (Halifax), May 18, 1971.

14. Colburn, H. N. (Director, Use of Tobacco Program, Department of National Health and Welfare) Unpublished information provided to the Commission, February and March, 1973.

15.Imperial Tobacco Products Limited, Public Relations Department. 1971: Review of the Canadian tobacco industry—The industry at a glance. Unpublished manuscript, Montreal, 1972.

16.Imperial Tobacco Products Limited, Public Relations Department. 1971: Review of the Canadian tobacco industry—Production of leaf tobacco grown in Canada. Unpublished manuscript, Montreal, 1972.

17. Ottawa City Police. Annual report 1969. Ottawa, 1969.

18. Toronto Star. 3 held after truck picks up cigarettes. Toronto Star. November 1. 1971: 44.

19. Wilde, O. J. On the steam run to Saint Peters. Time, September 20, 1971: 10-11.