| - |

Drug Abuse

B.7 MINOR TRANQUILIZERS, BARBITURATES AND OTHER SEDATIVE-HYPNOTICS

LEGAL SOURCES AND LEGAL DISTRIBUTION

The distribution of minor tranquilizers, barbiturates and other sedativehypnotics is regulated by the provisions of the Food and Drugs Act and its Regulations. Alcohol may also be considered a sedative-hypnotic drug, but is discussed separately in this appendix (see B.6 Alcohol).

The major and minor tranquilizers and the non-barbiturate sedativehypnotics listed in Schedule F of the Food and Drug Regulations may only be retailed on the written or verbal prescription of a licensed medical practitioner. These prescriptions can only be refilled if a practitioner so prescribes and may not be refilled more than the number of times indicated by the practitioner. The Food and Drug Regulations contain provisions regarding the manufacture, sale, importation, and labelling of Schedule F drugs. Sale of these drugs to a member of the public without a prescription is prohibited, but the unauthorized possession of them for personal use is not an offence.

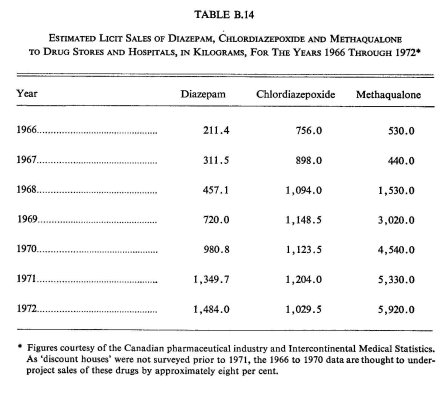

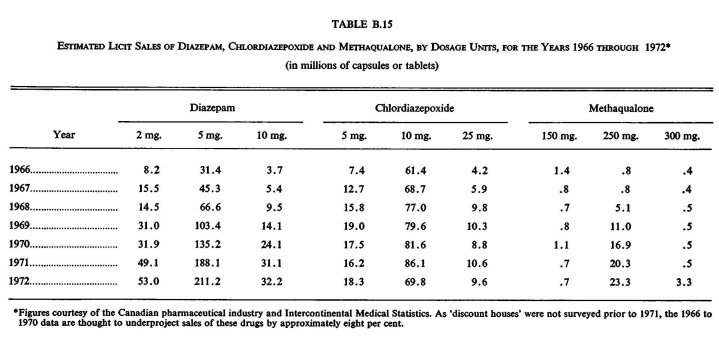

Distributors must, under certain circumstances, keep records of their distribution of Schedule F drugs. Manufacturers must also maintain samples of any Schedule F drug they manufacture. As there is no requirement to submit regular reports or returns of Schedule F drugs to the Department of National Health and Welfare as is the case with narcotic and controlled drugs, it is not possible to present an official statement of the annual estimated consumption of tranquilizers and non-barbiturate sedative-hypnotics.20 However, certain non-governmental estimates are available. For example, according to a Canadian Medical Association survey of prescribing habits conducted in February 1971, there were almost twice as many prescriptions written for minor tranquilizers and almost two-thirds as many for non-barbiturate sedative-hynotics as there were for barbiturates during a typical one-week period.'' Additionally, pharmaceutical market surveys of the estimated sales of two minor tranquilizers—diazepam (Valium® and Vivol®) and chlordiazepoxide (Librium®, Solium®, and others)—and methaqualone (a non-barbiturate sedative-hypnotic, including such preparations as Mandrax® and Mequelon®) have been provided to the Commission, and these data are presented in Tables B.14 and B.15.

Barbituric acid and its salts and derivatives are considered as "controlled drugs" in the Food and Drugs Act, and are therefore listed in Schedule G of this Act. The Food and Drug Regulations contain provisions dealing with the labelling of these drugs and prohibit the manufacture, sale, import and export of controlled drugs by anyone other than a licensed dealer who has been authorized to carry on these activities by the Minister of National Health and Welfare. Medical practitioners may only prescribe, administer, give, sell or furnish barbiturates to patients who are under their professional care and who require this drug for the condition for which they are receiving treatment. Hospitals are prohibited from dispensing or administering barbiturates without the authorization or prescription of a medical practitioner. Pharmacists may supply barbiturates to hospitals and, upon receipt of a written or verified verbal prescription or order, to private persons. Licensed dealers, pharmacists, medical practitioners and hospitals must keep records of all transactions involving controlled drugs for at least two years in a form which can be readily inspected, and must notify the Minister of National Health and Welfare of any "loss or theft of a controlled drug". Trafficking and possession for the purpose of trafficking in barbiturates (but not the unauthorized simple possession of them) are prohibited under the Food and Drugs Act.

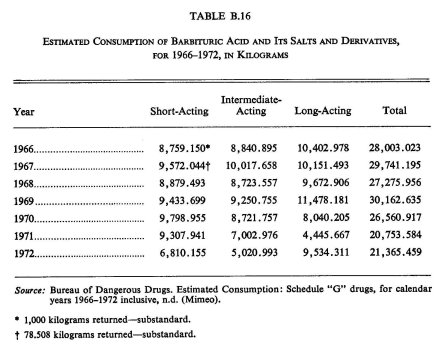

Barbiturates are generally divided into three categories: 'short-acting', `intermediate-acting', and long-acting' (see Appendix A.7 Barbiturates and Their Effects). Table B.16 shows the annual estimated consumption of each type of barbiturate based on the formula: Imports — Exports = Estimated (domestic) Consumption.* From this table it can be seen that there has been approximately a 24 per cent decline in the total estimated consumption of barbiturates between 1966 and 1972.

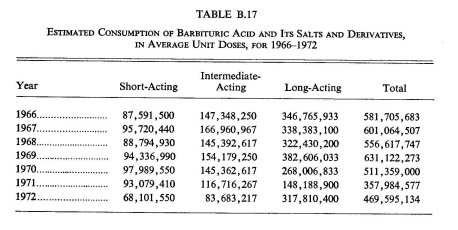

While there is considerable disagreement as to barbiturate standard-dose units (primarily depending on whether one is speaking of these drugs' use for day-time sedation or nocturnal sleep inducement), it is still apparent that Canadians consume a very substantial number of barbiturates. When the 'consumption' figures presented in Table B.16 are analysed in terms of the Bureau of Dangerous Drugs' standard conversion factors of 'average unit doses' (100 mg. for short-acting, 60 mg. for intermediate-acting, and 30 mg. for long-acting barbiturates),28 it can be seen that the estimated consumption for 1972 was nearly one-half billion barbiturate capsules or tablets. This is enough to provide every Canadian over 15 years of age with about 30.3 individual units of barbiturates. The estimated consumption of barbiturates in 'average unit doses' is presented in Table B.17.

* 'Estimated consumption' does not represent actual sales figures to hospitals and retail pharmacies but, rather, the amounts of barbituric acid and its salts and derivatives available for medical use. Some of the barbiturates included in 'estimated consumption' are thus at processing or wholesale levels of the distribution network and have not actually been consumed.

Combining the data presented in Table B.17 with those in Table B.15 indicates that the estimated consumption of sedative-hypnotic drugs in 1972 was over 890 million individual unit doses. As Table B.15 does not include several types of minor tranquilizers and non-barbiturate sedativehypnotics (such as meprobamate and glutethimide), it is not unreasonable to assume that actual 1972 consumption of all sedative-hypnotics was closer to one billion individual unit doses. This was sufficient to provide every Canadian over 15 years of age with approximately 64 individual units of these drugs in 1972.

LEGAL SOURCES AND ILLEGAL DISTRIBUTION

It appears that all the sedative-hypnotics and minor tranquilizers used in Canada, both medically and non-medically, originate from licit sources. Some diversion of these drugs at different levels of the legitimate manufacturing and distribution systems does occur, however, channelling these substances into the illegal market.

The legal status of barbiturates is different from that of the minor tranquilizers and the non-barbiturate sedative-hypnotics (see "Legal Sources and Legal Distribution", above). In 1961 barbiturates and amphetamines were legally classified as "controlled drugs" after the R.C.M. Police gained knowledge supporting the belief that there was a substantial underworld traffic in barbiturates in some dance halls, restaurants, cafés, and beer parlours. Stricter measures did not serve to totally erase the illicit sale of these substances, however, and a large black market in sedatives still exists. Although it is impossible to say how many sedative-hypnotics make their way into illegal distribution channels, it is certain that it is a large number. Many minor tranquilizers and sedative-hypnotics are illegally trafficked in Canada, and individuals in multiple drug-using scenes seem to have little trouble acquiring these drugs.

The minor tranquilizers and sedative-hypnotics make their way from the licit distribution system to the illicit one at various junctures. An unknown amount of pharmaceutical sedatives enter illicit channels of distribution through theft from manufacturers' and wholesalers' stocks. Commission field work in Toronto, during the summer of 1970, found that counterfeit Seconals® were being sold to multiple drug users, speed freaks and young heroin users. Illicit barbiturate dealers apparently purchased or otherwise obtained the secobarbital in pound lots and then 'capped' it themselves in gelatin capsules which were most likely procured from local drug stores.24 Similarly, a Montreal man was recently found in possession of 26.56 pounds of phenobarbital which were alleged to be part of a theft of 31 barrels of this drug from Montreal harbour in June 1972.'7. 23 In 1971 there were seven thefts of controlled drugs (barbiturates and amphetamines) from drug wholesalers reported by the Bureau of Dangerous Drugs.5 As tranquilizers and sedative-hypnotics are not "controlled drugs", there are no comprehensive records of thefts of these substances from manufacturers and wholesalers. It is to be expected, however, that these are stolen with at least the same frequency as barbiturates and amphetamines.

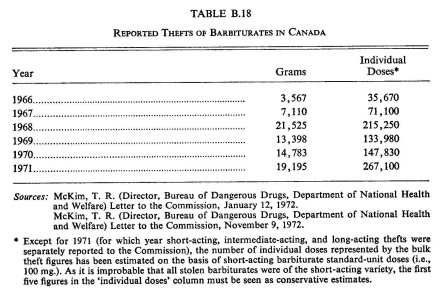

The minor tranquilizers, barbiturates and other sedative-hypnotics are most susceptible to theft when they are in the hands of the approximately 4,800 pharmacies in Canada. Preliminary Bureau of Dangerous Drugs tabulations indicate that there were 266 reported thefts of barbiturates during 1972.4 During 1971 the Bureau of Dangerous Drugs recorded thefts of 19,195 grams of barbiturates. This converts to more than one-quarter million individual doses stolen during that year. Table B.18 shows the thefts of barbiturates from 1966 to 1971. The first column represents the quantities stolen in grams, and the second column transforms the quantities stolen into the minimum number of individual doses that can be converted from these bulk amounts.

There is no doubt that thefts involving non-barbiturate sedative-hypnotics and minor tranquilizers also occur, as these drugs (particularly those containing methaqualone) are more widely available in the illicit marketplace than any of the barbiturate preparations.

At the retail level of the licit distribution system there appears to be some diversion of sedative preparations from pharmacies. Some users have informed Commission researchers that they have purchased such drugs from pharmacists who did not require a prescription.

At the lowest level of the licit distribution system, individuals who acquire prescriptions for sedatives may sell or give parts of their prescribed drugs to their friends and relatives. Although this type of distribution is technically illegal, it is often socially accepted, and has been found to exist among housewives, 'office buddies' and school mates.25 Mellinger, in a recent study of a random sample of more than 1,000 adults in San Francisco, found that 27 per cent of his respondents procured their prescription-type drugs (including sedatives) from non-medical sources.2' A 'friend' was the source usually identified; a 'spouse' was not as common a source, and wives were more likely to dispense these drugs (especially tranquilizers) to their husbands than vice versa.

The use of minor tranquilizers and sedative-hypnotics is fairly common among some groups of youthful multi-drug users." Diazepam (Valium()) and chlordiazepoxide (Librium()) particularly, but also the barbiturates, have been used in Canada since the explosion of cannabis and hallucinogen use in the mid-sixties to counteract 'freak-outs'. Speed freaks have also used minor tranquilizers and sedative-hypnotics to counteract the effects of the `crash' from extended methamphetamine use. In the last few years young persons have been increasingly using these drugs, either alone or in combination with other drugs, to achieve a 'stoned' state. A distribution system for these drugs has developed among multiple drug users in parts of Canada which is comparable to, and affiliated with, the distribution systems for cannabis and the hallucinogens.

The price of pharmaceutical sedatives on the illicit market is dependent, to a large degree, on their availability. Even in multiple drug-using scenes, where the normal course of affairs involves free distribution of small amounts of sedatives to those desiring them, shortages of these substances can force their sale to inflated prices.

In Toronto there is a well developed distribution system for barbiturates. During the summer of 1970, 50 100 mg. Seconals® sold for $15. The winter of 1970-1971, however, brought an over-abundance of these pills and a consequent reduction in their price; they sold for $25 per hundred doses.24 In 1968, in Vancouver, 200 mg. Tuinals® were selling on the illicit market to heroin addicts for one dollar. One hundred mg. Seconals®, although less popular, sold to heroin addicts for fifty cents each.8

Methaqualone, a non-barbiturate sedative-hypnotic, has recently come into widespread use among some groups of multi-drug users in eastern Canada, especially in the Ottawa-Hull and Montreal areas. Pharmaceutical preparations containing methaqualone have been fairly constantly available since late 1970, and they are occasionally obtained through thefts from warehouses. They can be illegally purchased for between $25 and $50 per 500 capsules and then eventually resold for between twenty-five and fifty cents each." During periods of relative drought, however, the price may rise as high as one dollar per capsule or tablet.

ILLEGAL SOURCES AND ILLEGAL DISTRIBUTION

Margaret Kreig, in her book Black Market Medicine, states that prescription-type drugs in the United States are increasingly originating from illegal sources." The basic chemicals are manufactured in bulk in clandestine laboratories or may be shipped illegally into the United States from abroad. These chemicals, on entering the United States, are converted into pharmaceutical doses, in which form they either remain in the illegal distribution system or else they enter the legal stream of prescription drug distribution to be sold in retail pharmacies as legitimate prescription drugs. In Canada there is no evidence of tranquilizing or sedative-hypnotic substances either being manufactured in Canada illegally or being illegally imported into the country. All of these substances appear to be imported legally into Canada before any diversion into illicit channels of distribution occurs.

References

1. Canada, Department of National Health and Welfare, Bureau of Dangerous Drugs. Estimated consumption schedule "G" drugs based on the deduction of exports from imports for calendar years 1962-1970 inclusive: Barbituric acid and its salts and derivatives. Unpublished manuscript, Ottawa, March 10, 1971.

2. Canada, Department of National Health and Welfare, Bureau of Dangerous Drugs. Estimated consumption schedule "G" drugs based on the deduction of exports from imports for calendar years 1962-1971 inclusive. Unpublished manuscript, Ottawa, May 10, 1972.

3. Canada, Department of National Health and Welfare, Bureau of Dangerous Drugs. Estimated consumption schedule "G" drugs based on the deduction of exports from imports for calendar years 1970-1971 inclusive: Barbituric acid and its salts and derivatives. Unpublished manuscript, Ottawa, August 23, 1972.

4. Canada, Department of National Health and Welfare, Bureau of Dangerous Drugs. Number of thefts involving specific controlled drugs during 1972, n.d.

5. Canada, Department of National Health and Welfare, Bureau of Dangerous Drugs. Reported thefts of controlled drugs during the calendar year 1971. Unpublished manuscript, Ottawa, n.d.

6. Canadian Medical Association. National prescribing habits survey. Unpublished manuscript, Ottawa, 1971.

7. Canadian Medical Association, Non-medical Use of Drugs Sub-Committee. Report to C.M.A. Board of Directors re final brief to the Commission of Inquiry into the Non-Medical Use of Drugs. Unpublished manuscript. Ottawa, 1971.

8. Cumberlidge, M. C. The abuse of barbiturates by heroin addicts. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 1968, 98: 1045-1049.

9. Curran, R. E. Canada and controlled drugs. Medical Services Journal, 1962, 78: 415-430.

10. Durrin, K. A. Diversion as a factor in illicit drug traffic. Drug and Cosmetic Industry, 1970, 107: 28-30, 126-127.

11. Franklin, B. A. Traffic in 'pep pills' and `goofballs' is linked to underworld. New York Times, February 1, 1965.

12. Green, M. Committed users study. Unpublished Commission research project, 1971.

13. Green, M., & Blackwell, J. C. Final monitoring project. Unpublished Commission research paper, 1972.

14. Harper, J. D. (Director of Public Relations, Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association of Canada). Letter to the Commission, September 23, 1970.

15. Harper, J. D. (Director of Public Relations, Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association of Canada). Letter to the Commission, December 3, 1971.

16. Kreig, M. Black market medicine. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1967.

17. La Presse. La police de Laval retrouve des barbituriques voles dans le port. La Presse (Montreal), October 18, 1972: 12.

18. McKim, T. R. (Director, Bureau of Dangerous Drugs, Ottawa). Letter to the Commission, January 12, 1972.

19. McKim, T. R. (Director, Bureau of Dangerous Drugs, Ottawa). Letter to the Commission, November 9, 1972.

20. McKim, T. R. (Director Bureau of Dangerous Drugs, Ottawa). Letter to the Commission, January 8, 1973.

21. Mellinger, G. D. The psychotherapeutic drug scene in San Francisco. In P. H. Blachly (Ed.), Drug abuse: Data and debate. Springfield, Ill.: C. C. Thomas, 1970. Pp. 226-240.

22. Murphy, C. Halifax report. Sub-study of M. Green, Committed users study. Unpublished Commission research project, 1971.

23. Nebbs, S. Bail granted in drugs case despite Crown's opposition. Montreal Star, October 20, 1972.

24. O'Neill, M. Monitoring study field reports: Toronto. Unpublished Commission research project, 1971.

25. Skinner, W. J. Abused prescription drugs: Sources of helpful drugs that hurt. In J. R. Wittenborn, H. Brill, J. P. Smith, & S. A. Wittenborn (Eds.), Drugs and youth. Springfield, Ill.: C. C. Thomas, 1969. Pp. 148-158.

26. Thompson, P. Prescribing practices. Unpublished Commission research project, 1971.

27. U.S. News and World Report. Booming traffic in drugs: The government's dilemma. U.S. News and World Report, December 27, 1970: 40-44.

28. Wilson, E. V. (Assistant Director, Bureau of Dangerous Drugs, Ottawa). Letter to the Commission, August 23, 1972.

29. Woolfrey, J. Winnipeg report. Sub-study of M. Green, Committed users study. Unpublished Commission research project, 1971.