| - |

Drug Abuse

B.2 OPIATE NARCOTICS

LEGAL SOURCES AND LEGAL DISTRIBUTION

Canada has not permitted either the manufacture or importation of heroin since January 1, 1955, although legal supplies still exist in a few hospitals, pharmacies and private clinics Significant quantities of other opiate narcotics in wide use for medical purposes are imported into this country. The uses to which these substances are applied are described in Appendix A.2 Opiate Narcotics and Their Effects. The procedures by which the distribution of these drugs are controlled are specified in the Narcotic Control Act and the Narcotic Control Regulations. All prescription sales must be recorded. Codeine phosphate at low dose levels, however, may be sold without a prescription and sales need not be recorded provided that preparations containing this drug meet certain rigid provisions described in the Narcotic Control Regulations. Records of all opiate narcotics transactions and all opiate narcotics stocks in the possession of licensed distributors, doctors, hospitals and pharmacists must be open to Department of National Health and Welfare inspection, and all thefts from these parties must be reported to the Bureau of Dangerous Drugs.

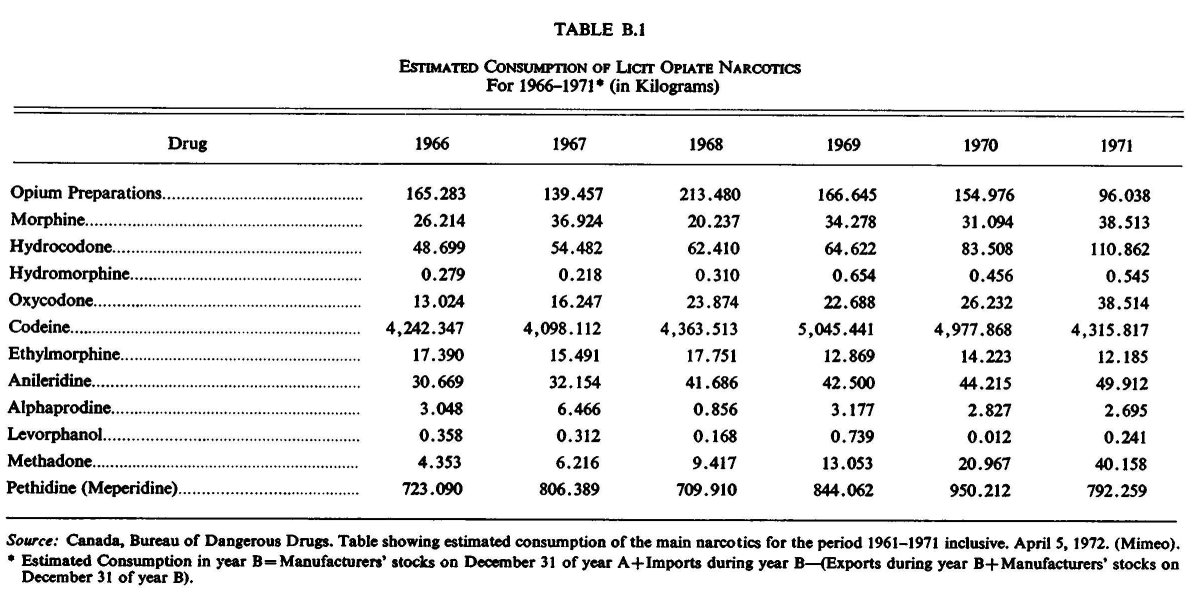

Table B.1 indicates the estimated consumption of the major opiate narcotics legally distributed in Canada between 1966 and 1971. Of special interest is the almost ten-fold increase in the consumption of methadone during this period. This drug is used almost entirely for purposes of methadone maintenance or the treatment of heroin withdrawal. Reported diversion of methadone into the illicit market (see "Legal Sources and Illegal Distribution", below) and concern over the misuse of this drug led to a governmental decision to restrict the right to prescribe methadone solely to those "physicians . . . authorized to do so by the Minister of National Health and Welfare."37 These more rigorous restrictions came into effect on June 1, 1972. At that time prescribing authorization was temporarily limited to about 800 practitioners. These temporary authorizations expired on October 31, 1972, and prescribing authorization renewals were issued effective November 1, 1972. At the end of November 1972, approximately 455 practitioners were authorized to use methadone, including eight veterinaries.

At present, a licensed medical practitioner may receive authorization to use methadone for the treatment of narcotic addicts, for the management of narcotic withdrawal, as an analgesic or anti-tussive agent in non-addicted persons, or for veterinary purposes. Over 70 per cent of the practitioners with the right to prescribe methadone as of the end of November 1972 were granted authorizations solely for the treatment of opiate narcotics addiction or withdrawal. The specific details of these authorization restrictions and their consequences are discussed in Appendix G.1 Methadone Control Program of the Government of Canada.

LEGAL SOURCES AND ILLEGAL DISTRIBUTION

Although the controls on the availability of opiate narcotics for legitimate medical purposes outlined above are quite rigorous, there is, nevertheless, some diversion of these drugs into the illicit market. The major forms of diversion include thefts from pharmacies, doctors (offices and bags), hospitals and licensed distributors, pilferage from warehouse stocks, obtaining prescriptions from a number of doctors, forging prescriptions, deceiving doctors by simulating withdrawal symptoms, and the overprescribing of opiate narcotics by a few doctors.34, 58, 68, 108

Apart from methadone, it appears that thefts are the major form of diversion and that these thefts generally net only small amounts of drugs.". 1°6 In the case of methadone, however, almost five times as much methadone seized by law enforcement officers was destroyed in 1971 (777 grams) as was reported stolen (157 grams) in that year.36,1°6 As there is no evidence of the illicit manufacture of methadone in Canada, nor of significant quantities of methadone being illicitly imported into this country, it is safe to assume that there was some misprescribing of methadone by doctors before the new methadone regulations of June 1, 1972. In fact, indications of overprescribing had been received prior to this date by the Department of National Health and Welfare20, 37' 57 and the Commission's own monitoring studies of drug use patterns in selected urban centres.", 58

The effect of the June 1 regulations on the diversion of methadone to the illicit market cannot be fully ascertained at this time. There is reason to believe, however, that the extent of such diversion has been significantly reduced.

ILLEGAL SOURCES AND ILLEGAL DISTRIBUTION INTERNATIONAL PATTERNS OF ILLEGAL DISTRIBUTION

The international trade in illicit narcotics is a complex phenomenon affecting both producing and consuming nations. However, the illicit trade is not universally perceived as a problem by the scores of nations involved as illicit producers, processors, shippers, or consumers. In several countries the illicit trade is an almost regular and traditional source of income for members of the government. Many of the producing nations simply lack the political power and financial resources to eradicate illicit cultivation, while other governments—often for political reasons—hesitate to deprive their already impoverished farmers of their major cash crop. However, one must also consider the inability of the consuming nations to curb illicit demand, successfully treat or control their user and addict populations, or control illegal distribution.

Although there are likely tens of thousands of illicit producers and approximately two and one-half million illicit consumers world-wide, most of the international illicit distribution system is controlled at the top by a relatively small number of professional criminal syndicates of primarily French-Corsican, Italian-Sicilian and Chinese backgrounds. Each syndicate is an independent, autonomous entity with virtually identical structures and styles of organization. They wield considerable power because of their wealth and their widespread corruptive influence on individual police, customs and government officials. These syndicates are specifically and effectively organized to minimize risks (especially for their senior persons), and do not hesitate to utilize the full measure of both legal and illegal means to protect their interests and evade prosecution. The illicit distribution system is extremely flexible; the closure of one opium source is usually followed by the spawning of another, as the trade shifts to the areas of least resistance.

The present international regulations regarding opium production and trade are embodied in the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotics Drugs. The Single Convention does not prohibit internal cultivation, production or consumption of opium, but it does establish certain obligations to diminish the possibility of overproduction and diversion to illicit market. Among other obligations, the signatories to the Convention must ensure that all aspects of their opium cultivation and trade relate exclusively to medicinal or scientific purposes.172 The enforcement provisions under the Convention are based on the force of world opinion. The official regulatory body has neither means nor power to physically interrupt illicit traffic, but must rely upon the diligence and honesty of domestic law enforcement agencies or mutual co-operation between nations.

OPIUM CULTIVATION, PRODUCTION AND CONSUMPTION: LICIT AND ILLICIT.

Poppy Cultivation

Opium is the hardened gum derived from the milky sap of the poppy plant (papaver somniferum). It is the proportion of morphine alkaloid in the opium that determines its commercial value. The plant grows in a variety of soils and requires a warm, fairly dry climate. The mountain valleys from the Turkish Anatolian Plain to the Yunnan Province in China are the sources of most of the world's opium.181 However, many other areas are entirely suitable for opium poppy cultivation.

The cultivation and especially the harvesting require tremendous amounts of labour. It takes between 175 and 250 hours of manual labour to produce one kilogram (2.2 pounds) of opium.181 The poppy acreage per farm is directly limited to the quantity that can be manually harvested during one day as each of the five to twenty pods per opium plant must be lanced and scraped to collect the opium gum within a 24-hour interval.182 Mechanical harvesting is possible but would require "sizeable capital outlays and .. . concentrated area of cultivation" which would be far too visible for illicit production.182 Because of the tremendous amount of labour involved, poppies tend to be raised only where labour is abundant and cheap; annual per capita incomes range from $350 in Turkey to less than $100 in India and Southeast Asia.182 Where there exist abundant opportunities for comparable legal income, opium is rarely produced. For example, in Yugoslavia licit annual production gradually fell from eighty tons to three tons as the per capita income rose in the primary producing province of Macedonia.173

Poppy cultivation usually represents a small fraction of total cropped land; in Turkey, Iran, Pakistan, Afghanistan and India it rarely exceeds one hectare (2.47 acres) per farm.181 The majority of the land is used for growing food for the farmers' needs. By contrast, in Southeast Asia poppy growing accounts for a far larger share of the cultivated land and is therefore more vital to the local farm economy.181

Yields, Purity, Prices and Economic Significance

Regional yields per unit of land vary considerably: from twenty kilograms per hectare in India to eight to ten kilograms per hectare in the opium growing areas of Burma, Laos and Thailand."' Turkish opium yields of 15 to 16 kilograms per hectare are comparable to Indian opium yields because the latter are adulterated and hence yield less morphine alkaloid. In addition, the yield per farm within each region may vary due to the quality of the seeds, the amount of weeding, fertilizer and irrigation, the timing of the harvest, and other factors.181 Opium cultivation is extremely risky. An entire crop might fail,108 and rain during harvest may leach out the morphine alkaloid."' The widespread variation in possible yields makes it extremely difficult for a legal government opium monopoly to prevent diversion to the illicit market. The farmer may understate his output by as much as 25 per cent and still be well within the wide range of possible yields.

The morphine content of the opium defines its purity and value.181 Although the estimates of purity vary, it is generally conceded that Turkish opium (with a morphine content of between nine and fifteen per cent) is the world's most potent.108, 181 The opium produced in other countries has a morphine content ranging from 4 to 12 per cent.

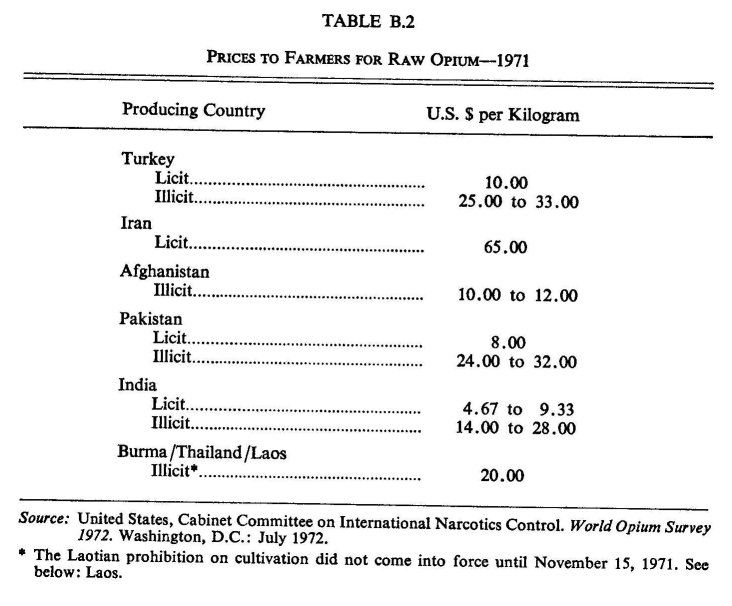

Generally speaking, the price of opium decreases from Turkey east to Southeast Asia."' The opium farmer's returns for his hundreds of hours of labour are extremely meagre by North American standards. For example, the Turkish opium farmer in 1971 would have realized only about five cents per hour on the legal opium market or fourteen cents per hour for illicit sales.31. 182 Table B.2 indicates the range of opium prices on the international licit and illicit markets in 1971.

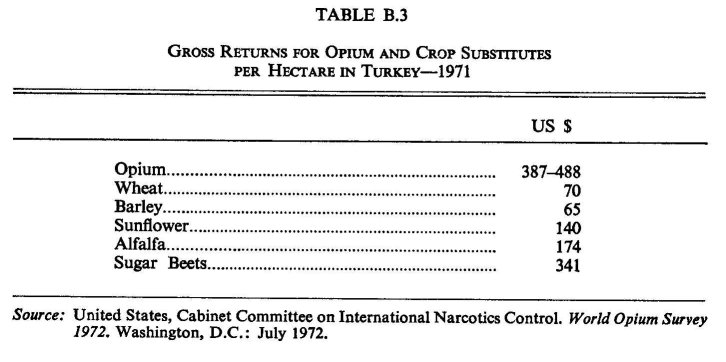

The economics of opium cultivation at the farm level is a crucial factor affecting international efforts to suppress the illicit opium trade. In large part, the suppression of this trade is dependent upon replacing present opium cultivation with alternate crops of equal or greater value per unit of land. Although other crops yield more per hour of labour, no legal substitutable crop provides comparable economic yields per hectare (see Table B.3 below), and in the opium producing countries labour is cheap and land is expensive.181

The economic, social and political problems of undertaking crop substitution in the western opium-producing nations are less complicated than those in Southeast Asia where opium represents a far greater percentage of total cropped land.158. 181 Furthermore, governments in Southeast Asia lack the resources to enforce their narcotics laws in the remote areas in which opium is cultivated as government officials have little effective contact with these regions.173 Widespread personal use of opium among its growers in Southeast Asia increases the problems of crop substitution and the suppression of opium production.

Licit Production and Uses

The United States Cabinet Committee on International Narcotics Control estimated that approximately 1,500 metric tons of opium were produced in 1971 for the world's licit market.'82 Higher production levels in India and the resumption of large scale cultivation in Iran increased the 1971 licit supply by 25 per cent. India produced 62 per cent of the licit total, the U.S.S.R. produced about 13 per cent, and Iran and Turkey each accounted for about 10 per cent. The People's Republic of China, Pakistan, Japan, Yugoslavia and North Vietnam accounted for the remainder of the licit production. The processing of poppy straw (the pods and upper parts of the stems), which is the alternative to raw opium as a source of morphine, has increased over the past decade and presently accounts for 35 per cent of licit morphine production.182

A relatively small quantity of licit opium production is used to provide maintenance doses of opium for registered addicts in the government treatment programs of Iran, Pakistan and India.182 However, 90 per cent of the licit supply is converted to morphine, and 95 per cent of this morphine is used to produce other substances, chiefly codeine.182 Although some synthetic alternates are available, no completely satisfactory substitutes for codeine have yet been found.ss. 169, 182

Illicit Production and Consumption

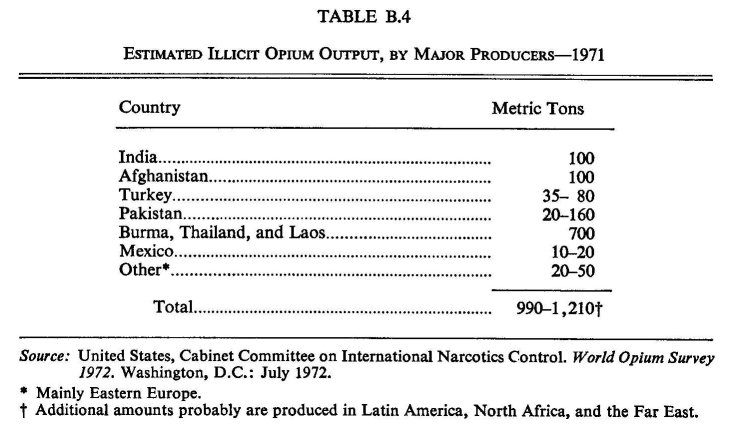

The American Cabinet Committee has estimated the 1971 world illicit opium production at between 990 and 1,210 metric tons (see Table B.4).182 Burma, Laos and Thailand accounted for 63 per cent, India, Afghanistan and Pakistan each accounted for about nine per cent, and Turkey supplied five per cent of this total. The remaining five per cent was primarily produced in Eastern Europe and Mexico with additional scattered cultivation in Latin and South America, North Africa and the Far East", 182 The United States Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (B.N.D.D.) has stated that illicit production in the People's Republic of China, U.S.S.R., Eastern Bloc nations and North Vietnam is insignificant.181 Substantial increases were expected in the 1972 illicit supply due to bumper crops in Burma, Laos and Thailand."

Most of the illicit opium is consumed by users within or close to the areas of cultivation. Southeast Asia—representing the largest consuming population—absorbed 600 of the 700 tons produced in Burma, Laos and Thailand in 1971.182 However, the American Cabinet Committee estimated that a minimum of 200 tons of the 1971 illicit world-wide opium supply and substantial illicit stocks from previous years were available for the international heroin market, which is primarily composed of about 575,000 North

American heroin dependents.182 These addicts consume over 11 metric tons of pure heroin annually. In terms of opium equivalents, the North American market thus requires 110 metric tons of raw opium, or ten per cent of the 1971 illicit supply. This market is probably the world's most lucrative as heroin is far easier to import and far more profitable to distribute than any other form of narcotic. Furthermore, North American heroin addicts and users are able to pay far higher prices than their more impoverished counterparts in Europe and Southeast Asia.

THE INTERNATIONAL DISTRIBUTION OF ILLICIT NARCOTICS: A HISTORY SINCE 1940

Since World War II, the illicit demand for opiates has increased substantially in most countries that have experienced serious narcotics problems in the past, with the exception of the People's Republic of China and Iran."' Prior to 1940 Mainland China was the largest illicit market for opium products, several times larger than the rest of the world combined."' At the beginning of World War II China had an estimated opium-smoking population of ten million, concentrated in the larger urban centres on the Pacific Coast.'" This vast market was primarily supplied by India and Iran, the two largest illicit producers at the time, with smaller quantities from Egypt, Pakistan and French Indo-China.*181 In addition, prepared smoking opium and other opiates shipped from China supplied the large Chinese using population in Southeast Asia and North America until the beginning of World War II when the Pacific shipping lines were cut, temporarily ending the major role played by the Chinese in North American opiate distribution.38

The vast illicit market in China largely disappeared when the People's Republic of China was formed in 1949, and thus the international trade in illicit narcotics changed as the world demand for opium drastically declined.'" The Chinese criminal syndicates that had controlled the trade in Mainland China resettled in Hong Kong and other parts of Southeast Asia, and apparently maintained their contacts with the Chinese syndicates in North America.32 Following closure of the Chinese market, Iran became one of the leading producers and exporters of illicit opium; well over one-half of Iran's licit opium crop was diverted to its domestic black market, the Southeast Asian market and the small but growing demands of the North American market. The illicit trade in Western Europe became increasingly important when Italy banned legal heroin production in the early 1950s—Italy having been the major source of supply for the North American east-coast addict population. During this period Turkey developed as a significant opium producer. Turkish opium, diverted from legal production, was transported directly, or through Syria and Lebanon, to France and Italy for refinement into heroin."'

• French Indo-China encompassed what is now Laos, Vietnam and Cambodia. The Geneva Agreements of 1954 established these countries as independent nations.

Iran, with an addict population of about one and one-half million, banned all opium cultivation in 1955, thus creating a shortage in Southeast Asia, the Middle East and Western Europe.* The United States B.N.D.D. has indicated:

In order to meet demand in Iran, illicit production rose sharply in both Afghanistan-Pakistan and Turkey. After the elimination of supplies from China and Iran to the Far East and Southeast Asia, production also rose substantially in Burma, Laos, and Thailand. In addition, with the elimination of Iran's formerly westward-moving illicit exports, Turkey largely filled the gap by increasing its exports to the Arab countries, Western Europe, and North America."'

Southeast Asian opium production increased prior to and after the Iranian opium prohibition. Alfred McCoy has reported that the Kuo Min Tang (K.M.T.) in Burma,t General Phao Sriyanonda in Thailand4 and the intelligence arm of the French Colonial Government in Indo-China (Service de Documentation Exterieure et du Contre-Espionage or SDECE) discreetly encouraged expansion of Southeast Asian opium cultivation following World War II.105 After the 1954 Geneva Agreements and the French withdrawal from Southeast Asia, elements of the newly founded national governments of Laos and South Vietnam and the American Central Intelligence Agency (C.I.A.) began to play a role in the Southeast Asian opium trade. During the 1950s and 1960s, members of the French-Corsican criminal syndicates of Saigon shipped Southeast Asian morphine base to the French-Corsican heroin refineries of Marseilles.105

Following the 1955 Iranian prohibition, Turkey became the most significant source of illicit opium for the heroin refineries of Southern France and those few that existed in Italy.181 As the number of Turkish hectares under opium production declined during the 1960s, the percentage illegally diverted increased and thus the quantity reaching the illict market remained unchanged.18' It was not until the United States threatened to cut back foreign aid and favourable trade agreements in the late 1960s that the Turkish Government initiated rigorous programs to reduce its illicit cultivation and trade.156 The reduction in the number of opium-growing provinces, the strengthening of the licensing system, closer supervision of opium farmers, an increase in the government price for licit opium, and the development of a large narcotics enforcement branch substantially decreased the quantity of opium reaching the illicit market.31- On June 30, 1971 the Turkish Government announced it would ban all opium poppy cultivation as of autumn 1972.1" Several months later the United States pledged $35 million to support bilaterally developed agricultural and financial programs to ease the economic hardships resulting from the Turkish ban.182

• Iran's narcotics-using population decreased significantly during this prohibition; the 1971 addict population was roughly estimated to be 400,000 persons. Licit opium production was resumed in 1969.182

t See below, "Burma".

# See below, "Thailand".

There is significant public opposition to the opium prohibition in Turkey which is linked, to some extent, to growing anti-American sentiment; Istanbul's major newspaper Hiirrifet has protested United States interference in the internal affairs of Turkey, and the opposition party in the Turkish Parliament has introduced two bills to repeal the opium poppy ban.163 Even if the cultivation prohibition is maintained, as is expected,32 the huge supply of opium illicitly stockpiled by Turkish farmers will temporarily ease the shortage caused by the ban.109, 182

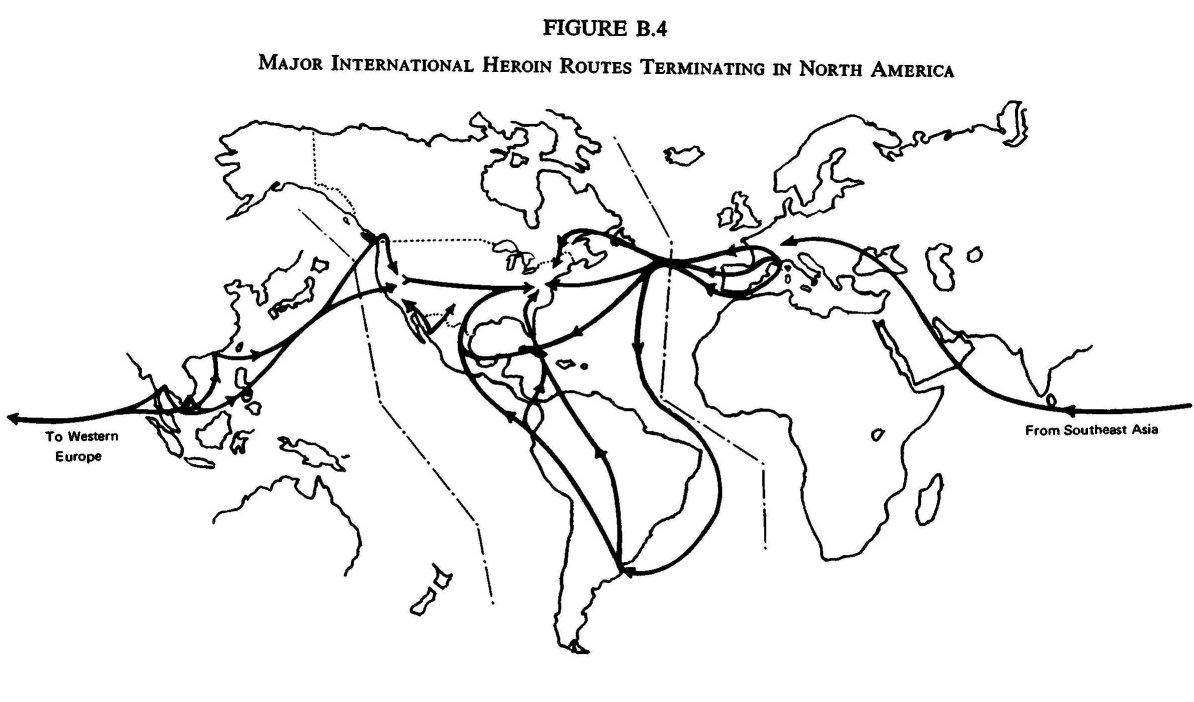

Since World War II, three distinct areas of illicit production and refinement have supplied the North American heroin market: The Middle East, Southeast Asia and Mexico.31, 181 Until the late 1960s, the Middle East accounted for up to 80 per cent of this supply.181 However, the Turkish opium production ban has already caused major changes in the international distribution system and is likely to precipitate other changes in the near future.105, 181, 182 Some sources suggest that Southeast Asian heroin may soon dominate the North American market.32, 105 The opium-producing complex of Iran, Afghanistan, India and Pakistan, which accounted for over 25 per cent of the world-wide 1971 illicit supply, may for the first time play a role in supplying the North American market.32

According to Interpol officials, at best only five to ten per cent of all illicit narcotics are seized before they reach their destination.173

THE MIDDLE EASTERN NARCOTICS TRADE

Control of Refinement and Demand: A Brief History

The illicit flow of raw opium and morphine base from the Middle East to the criminal syndicates of Western Europe has persisted relatively uninterrupted since the end of World War II. The traders and smugglers of Beirut and Istanbul have long dominated the collection of illicit raw opium, its processing into morphine base, and sale of the base to European syndicates." The most significant changes in the Middle Eastern market involve the roles of the Italian-Sicilian syndicates (hereinafter referred to as the `Mafia'*) and the French-Corsican syndicates in the refinement of morphine base into heroin. These syndicates are strikingly similar in structure and organization: both are organized along family lines with a strong sense of loyalty and strictly enforced codes against betrayal. In addition, both groups have developed extensive financial, criminal and political power, extending their influence far beyond their native island or country.

* There are at least three groups of criminal syndicates which trace their origins back to Italy and Sicily: the Neopolitans, the Calabrians, and the Sicilians. Although these three groups draw distinctions among themselves, for our purposes they will be collectively referred to as the 'Mafia'.

By the end of World War II, the Mafia, due largely to the organizational skill of Salvatore (Lucky) Luciano, controlled most American organized crime, including narcotics.99 In 1936 Luciano was given a 30- to 50- year sentence for 62 counts of compulsory prostitution, but was granted an early parole, for encouraging American east-coast dockworkers to fight German sabotage, and was then deported to Sicily.53 Even after his 1946 deportation Luciano remained a dominant force in North American organized crime, and his heroin distribution network in the United States was inherited by other mafiosi.31

The French-Corsicans' involvement in international organized crime was even more extensive than the Mafia's. Following the Second World War the French-Corsican syndicates gained control of the Marseilles docks24, 27, 105 and, shortly thereafter, opened the first illicit heroin laboratories in the Marseilles area.28 This area has remained the largest centre of illicit refinement for heroin entering the North American market.31, 32

French-Corsican syndicates also controlled a major part of organized criminal activities in French Indo-Chinalo and Lebanon, a former French protectorate and the centre of the Middle East narcotics trade.59 In addition, the French-Corsicans had established connections in Montreal, Buenos Aires, Rio de Janeiro, Mexico City, and pre-Castro Havana, thus linking them to the South American cocaine market.99. 163 The various French-Corsican syndicates and their associates were involved in almost every major illicit narcotics market, with one exception: North America, which was controlled by the Mafia.

Seven months after his deportation to Sicily, Luciano was reported to be in Cuba in the company of several American Mafia leaders.9, 192 The American Government brought pressure to bear on Cuba, and Luciano was forced to leave, resettling in Italy. However, pre-Castro Cuba developed into a major trans-shipment centre for heroin destined to North America from Europe and cocaine destined to Europe and the United States from South America.144

Heroin production was legal in Italy at this time and Luciano made arrangements with the managers of some Italian pharmaceutical companies to divert portions of their legal narcotics supplies into the illicit heroin market. Although the Italian authorities were notified of these companies' involvement in 1950, no action was taken until January 1953 when these managers were finally arrested and eventually imprisoned.99, 121, 192 Luciano, however, was not prosecuted, " ... the Italian authorities claiming that there was not sufficient evidence against him to warrant a charge."121 This affair precipitated a strong reaction in the United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs and eventually led to Italy banning all heroin production.192 As the Italian sources closed down, Luciano turned to the French-Corsican syndicates of Marseilles for pure heroin and to the Middle East for morphine base. The Mafia developed two concurrent systems for heroin importation into North America; they operated their own heroin conversion laboratories in Sicily, shipping the pure bulk heroin to North America via unsuspecting Italian immigrants. The second system was supplied by the French-Corsican heroin conversion laboratories of Marseilles; Corsican seamen smuggled the heroin into North America aboard regular commercial vessels. In both cases New York was the primary port of entry.99, 121, 144

In April 1957, 20 kilos of heroin destined for New York were seized from the S.S. Excambion in Marseilles harbour.144 This seizure of heroin was not as significant as the prosecutions that eventually arose from the case. Although the exact sequence is unclear, Vito Genovese and 14 of his Mafia associates were eventually arrested and charged with conspiracy to import heroin.?

In November 1957, more than a hundred Mafia chiefs and lieutenants met at Appalachin, New York. Among the major issues to be considered was a decision of the Mafia bosses to abandon the heroin business due to rising police pressure and increasing risks of prosecution.31, 100 The meeting was interrupted by the police before this topic could be discussed, but the narcotics trafficking prohibition was later revised to allow Mafia members to retain control of heroin importing and primary distribution as long as they did not endanger the non-drug enterprises of other Mafiosi.31 Within three years, however, another fifty leading members of the Mafia were arrested in two other major heroin conspiracy cases.7. 59' 99

The Mafia's role in international heroin distribution was substantially altered by the 1957 Appalachin edict and these three conspiracy cases. The Mafia maintained control over North American demand but abandoned heroin refinement and the actual smuggling into North America.69 By the beginning of the 1960s the French-Corsican syndicates controlled virtually all heroin conversion in the Middle East and Europe.

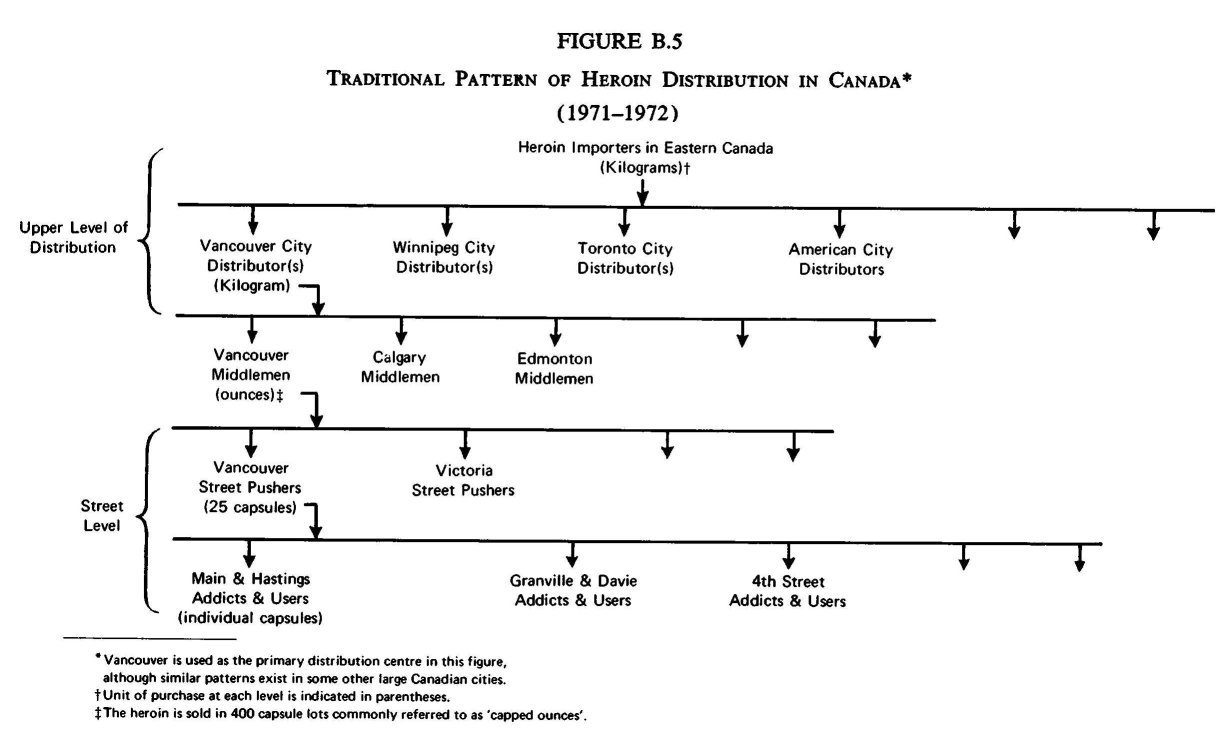

Deterioration in the relations between the French-Corsicans controlling supply and the Mafia controlling demand, coupled with the increasing sophistication of New York customs and narcotics agents, resulted in a diversification of importation routes into North America in the early 1960s. Montreal was the most important alternate route during this period because of its proximity to the huge New York heroin market. In addition, the Montreal syndicates proved more trustworthy than the New York Mafiosi, and law enforcement was not as vigorous.59 During the early 1960s the French-Corsicans still did most of their own importing but, with increasing police pressure, prosecutions and seizures, they were forced to specialize. They left the smuggling of heroin to their clients, hired independent couriers, and relied more heavily on primarily French-Corsican contacts in South America, Latin America, Montreal, Miami, New York, Spain and Italy to import the heroin for them.3' As the number of connections increased, the trade became more diverse and new routes and distribution patterns developed. However, the French-Corsicans remained by far the major supplier, and the Mafia on the American east coast remained their largest buyer.31, 146

The Supply, Logistics and Processing of Opium in the Middle East and Western Europe

From the farmer to the smuggler. According to the American B.N.D.D., Turkey was the source of opium for 80 per cent of the heroin consumed in Western Europe and North America following Iran's prohibition of opium production in 1955.181 This figure was probably accurate up until six or seven years ago, before the reduction in Turkish opium production and the expansion of the Southeast Asian trade. Under the pre-1972 Turkish licensing system, the farmer's opium acreage was not limited providing he lived within an authorized opium-producing province.'" At the beginning of each growing season Turkish farmers reported their poppy acreage and expected yields to the regional government opium monopoly, but since the planting and harvesting were not supervised the farmers simply underestimated their actual acreage or expected yields. The excess was sold to "commission men"—agents touring the producing area purchasing opium for illicit dealers. It may take two or three years before the 1972 ban on Turkish opium cultivation markedly reduces illicit shipments to Western Europe; Turkish and American narcotics officials attribute this potential delay to existing illicit stockpiles and possible clandestine cultivation.88

The collection and refinement of the opium, and the transportation of the morphine base, are the responsibilities of hundreds of professional smugglers." The entire illicit opium industry in the Middle East is viewed as a profession, and corruption of public officials, smuggling and violence are an inevitable part of this enterprise.'08 Once the morphine base is delivered to Istanbul or one of the other Turkish collection centres, it is transferred to the smuggler's agent for safekeeping until final arrangements are made with larger dealers.

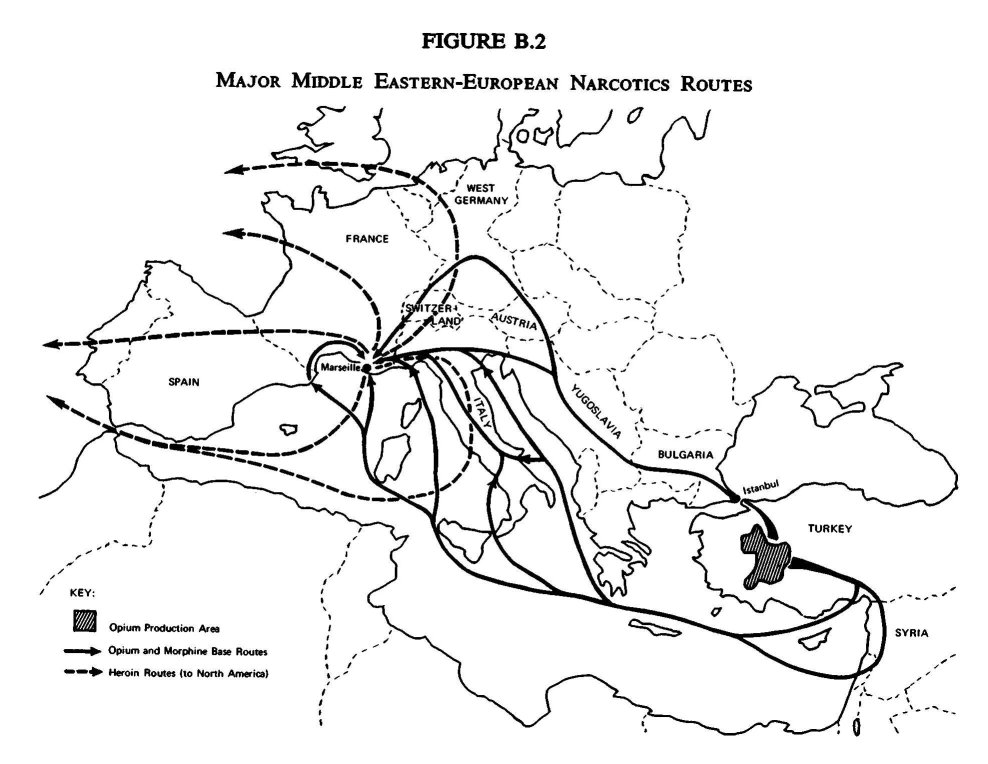

From the Middle East to the European refining laboratories. Middlemen in Germany, Italy and other Western European countries control much of the movement of morphine base from Turkey to France. These middlemen have developed their own connections in the Middle East and act either as forwarding agents for the French buyers or as independent suppliers.182 Independent entrepreneurs attempting to buy morphine base in the Middle East or sell it in Western Europe generally lack the contacts to survive.

Traditionally the morphine base was smuggled by ship into Marseilles, but recently the use of overland routes from Turkey through Bulgaria and Yugoslavia to Western Europe has increased significantly.59, 182 There are numerous explanations for this: a larger percentage of the opium is now converted into morphine in Turkey rather than Syria; the overland transportation system has improved; the Bulgarian and Yugoslavian border guards are rather lax; and increasing vehicular traffic makes the likelihood of a thorough search improbable.", ". 182 The most popular method of smuggling involves the use of false compartments or traps built into passen er cars and commercial trucks and buses.182 Approximately one-half milli° Turkish labourers are bnow in West Germany and they provide more than an ample number of willing couriers.* 31, 42, 182

West Germany has become a major staging area for huge stockpiles of morphine base en route to Southern France, but increased domestic concern and stricter, narcotics and customs enforcement may change the present German situation.32. 182 Italy is also a major trans-shipment point for morphine base en route to France; however, the prospects of improving Italian enforcement efforts are poor according to an international study conducted by U.S. Congressmen Murphy and Steele."9 Since the Italians have no domestic heroin problem, they do not see the need for strict enforcement; the Italian police agencies are fragmented and do not co-operate well with each other or international narcotics enforcement agencies. In addition, "the Mafia is deeply involved in the narcotics traffic, and high-ranking Italian government officials aid that organization throughout Europe.',109 Reports of heroin refineries operating in West Germany, Italy and Sicily have not been confirmed;19, 69, 109' 182 however, the present distribution system would encourage such developments.

The processing of morphine base into heroin. According to Collins and Lapierre, the conversion of morphine base into heroin "is a straightforward but nonetheless exacting chemical process".42 The so-called "heroin chemists" learn the trade through apprenticeship to other heroin chemists; the basic equipment is easily obtained and only small amounts of common industrial chemicals are needed (see Figure B.1). Even the large sophisticated laboratories in Europe cost as little as $4,000 to equip, and the floor-space requirements are small. The French laboratories each produce an average of about 20 kilograms of heroin per week, and will be shut down, dismantled and moved if there are no further conversion shipments or if police surveillance is suspected. The end product of this conversion process is a fine, fluffy white powder of approximately 90 per cent-pure heroin. Since the molecular weight of heroin is heavier than that of morphine, each kilogram of morphine base yields slightly more than one kilogram of heroin. Generally the laboratories operate on a commission basis, charging several hundred dollars for each kilogram of heroin produced; however, a smaller number of laboratories purchase their own supplies of morphine base and sell their heroin directly to international traffickers.42, 182

Routes and methods of smuggling heroin into North America from Europe. The French heroin trade is dominated by a few large French-Corsican trafficking groups; only recently have non-Corsican French traffickers entered the heroin trade 9s, 182 Although the majority of the heroin refineries are still located in the Marseilles area, several laboratories have recently been established in other parts of France.73 Until the 1970s, domestic narcotics enforcement in France had been hampered by the political influence of the French-Corsican syndicates, general French apathy towards the problem, and limited enforcement resources.31, 156

French efforts to curtail the illicit refinement of heroin apparently increased two or three years ago with the major expansion of their narcotics squad and the establishment of narcotic enforcement training programs.42, 48, 49 Part of this increased concern was the result of direct pressure repeatedly applied by the American Government at the presidential, cabinet, diplomatic and international enforcement levels.42' 55, 93' 155, 156 Despite an increase in the number of arrests and seizures, reports in the summer of 1971 indicated that the French heroin laboratories continued to prosper." In August 1971 John Cusack, head of the European branch of the American B.N.D.D., alleged that French police were deliberately overlooking the activities of the Marseilles heroin syndicates.66, 94 These charges were denied by the French Government and police, but subsequent arrests, seizures, and discoveries of heroin laboratories in the Marseilles area tend to confirm Cusack's statements.55' 66' 82. 94

* Labourers are not the only Turks involved in opiates smuggling, A Turkish senator was recently arrested at the French-Italian border en route from Turkey to Marseilles when 320 pounds of morphine base was found hidden in his car. Three other Turkish senators were implicated in the case.1.1"575

Following Cusack's charges there was an unprecendented series of major arrests of heroin refiners and traffickers in southern France.32 The recent development of a large heroin-using population in France has provided further impetus for improved enforcement efforts.32. 42, 55 A series of arrests beginning in September 1971 against one trafficking syndicate eventually resulted in the seizure of over 600 pounds of heroin in France and New York and 23 arrests.98, 112, 128 In the same month, 45 French members of another trafficking syndicate were arrested for conspiracy to import heroin into the United States.52 Furthermore, in November 1971 Roger DeLouette, a former employee of the French intelligence agency SDECE, was indicted on charges of importing 96 pounds of pure heroin into New York.

The largest seizure to date occurred near Nice in March 1972 when 935 pounds of pure heroin were found aboard the shrimpboat of Marcel Boucan, a known cigarette smuggler. Boucan was believed to have transported two previous heroin shipments to French-Corsican contacts in Latin and South America.92, 115, 177 French narcotics officers have not only continued to make major arrests of traffickers but, in the first seven months of 1972, they also arrested several of the more renowned "chemists", seized fairly large quantities of heroin and uncovered five heroin refineries.42, 96 During the entire previous decade only six heroin laboratories were discovered in France.96

The American Cabinet Committee has provided the best brief description of European smuggling methods:

The most common known means of smuggling heroin into the United States are by body or baggage carry, by concealment in a motor vehicle or other sea freight, and by clandestine air transport. A body carry usually consists of smuggling a small amount of heroin by strapping it to the body or concealing it in one's clothing or body cavities. Frequent use is also made of airline passengers and crews and seamen who carry heroin concealed in their personal effects or baggage.'

It should also be noted that some of the most successful heroin-smuggling operations have involved the use of diplomatic officials with formal customs immunity.26, 59, 71, 99, 116

Twenty-five years ago, when the Mafia controlled refinement, importation, and distribution of North American heroin, two basic routes, and two or three ports of entry were used. However, as the number of refiners, importers and key distributors increased, and as law enforcement efforts improved, the routes, methods of smuggling and control of the North American market became more diverse and fragmented.31 The problems of identifying, let alone arresting, the new individuals involved are consequently that much more difficult. Unlike the situation a decade ago, a single major seizure or the arrest of one large-scale trafficker has virtually no impact on the street availability of heroin.31 Numerous major seizures within a short period of time are now necessary to affect street-level supplies of the drug. The American Cabinet Committee indicated that there were three basic routes used to smuggle heroin from Europe into the United States: from Europe directly or via Canada, from Europe via Mexico, and from Europe via various other countries in Latin and South America and the Caribbean.182 As in the past, New York is the largest North American consumer market as well as the major clearing-house for heroin distribution. The Cabinet Committee has provided a concise description of the first major route:

The direct Europe-US route is the oldest French heroin smuggling route and remains the most active. Direct shipments to the United States enable the French traffickers to avoid using foreign middleman smugglers who might otherwise establish a closer relationship to the US buyer. The French smugglers have the advantage of concealing their shipments within a huge volume of transatlantic commerce and need pass through only one customs check. The risk to the French traffickers, however, is much greater since the arrest of a courier in the United States, has often implicated the entire trafficking group.

Canada serves two primary roles in the movement of French heroin from Europe to North America. French traffickers may use the Canadian route as an alternative port of entry into the United States in the belief that customs inspections in Canada and on the Canada-US border are more relaxed than on the east coast of the United States, particularly when French passengers are involved. Canadian traffickers themselves also purchase sizable quantities of French heroin for distribution in Canada and/or resale to U.S. traffickers.'

The second transportation network is apparently dominated by a small number of distribution agents operating out of Mexico City who appear to control the importation of pure European heroin and its resale to the large American east-coast syndicates.31. 99 These dealers are also involved in the South American cocaine trade, but generally do not handle the Mexican-grown opium products. Mexico first developed as a significant alternate route to the American east-coast market in the 1950s when first New York, and then Montreal and Toronto, tightened up their customs and law enforcement efforts.31

Considerably less is known about the Latin and South American route. The smuggling of South American cocaine to North America is a long-established and growing phenomenon, but it is not known when European distributors began to use this route. The leaders of many of the Latin and South American trafficking groups are of French-Corsican or Italian background and have close ties with their countrymen in Europe. Although it was first thought that these trafficking groups were independent buyers and sellers, it now appears that most simply act as agents for the large French-Corsican distributors and their Mafia buyers in the United States.32 The European heroin is believed to enter South America primarily through Bueno Aires and Montevideo, and is then distributed to various smuggling groups for reshipment to the United States.182 Much of the clandestine trade passes through Panama and Paraguay which serve as convenient refuelling and trans-shipment points; their limited border and narcotics enforcement has little impact on this illicit flow.32, 116, 139, 143, 191 The bulk of this heroin is smuggled into the southern United States aboard small private planes and boats.32, 43, 104, 116 Over the last five years roughly 30 per cent of the European heroin entering the United States arrived via South and Latin America (excluding Mexico) 32 One indicator of the popularity of this South and Latin American route is the recent emergence of Miami as a major port of entry; in 1971 over 460 pounds of pure heroin were seized in Miami and in the first month of 1972 two related seizures netted an additional 385 pounds of heroin.", 104 Although Puerto Ricans, expatriate Cubans and, to a lesser extent, American blacks are major importers and distributors of cocaine, they are generally limited to the role of lower-ranking employees in the Latin American heroin traffic route.32, 105

Customs and narcotics enforcement throughout Latin and South America has been superficial due to lack of concern, a shortage of enforcement resources, and the particular geographical and physical problems of border surveillance. The United States has applied considerable economic and diplomatic pressure to obtain governmental co-operation in some Latin and South American narcotics cases.79, 116, 139, 143, 190 For example, the United States indicted Auguste Ricord in March 1971 for conspiracy to import 97 pounds of heroin into New York, and it took 16 months to complete his extradition from Paraguay.no, 111, 140 In order to obtain Ricord, who is considered to be one of the top ten heroin distributors in the world, the United States Government, according to Newsweek:

... planned to "snatch" him from Paraguay and fly him to the States without benefit of formal extradition proceedings. Paraguayan authorities were willing enough, but the U.S. Ambassador ... reportedly blocked the idea. Then a lower court judge ... [ruled] that Ricord could not be extradited because drug trafficking is not listed in Paraguay's extradition pact with the U.S....

Impatiently, the U.S. turned the screws on Paraguayan President Alfredo Stroessner. More than $5 million worth of credit lines quietly dried up, U.S. military aid to Paraguay was halted and Stroessner was warned that funds from international lending organizations might also be affected. When the Paraguayan President passed through the U.S. last April en route to and from Japan, he was diplomatically snubbed and, for the first time since 1861, the U.S. ambassador cancelled the traditional Fourth of July party—the diplomatic event of the year in Asuncion. Finally, ... Gross [the U.S. State Department's top narcotics official] was sent to Paraguay . . . as a personal emissary from President Nixon ....

[Eventually] three appeals court judges overturned the lower court verdict and approved Ricord's extradition.'

International co-operation and narcotics enforcement efforts have apparently improved in parts of South America in the last year as evidenced by the growing number of arrests and major seizures. In August 1972 the Argentinian police seized 100 pounds of heroin in Buenos Aires; in the same month Venezuelan police seized 53 pounds of heroin, and in October and November the Brazilian police confiscated 132 pounds of heroin and claimed to have arrested the major figures in a Mafia-related international distribution network.32, 129 In addition, the Brazilian Government has recently deported several international heroin trafficking figures to the United States and Italy to face criminal charges.% 12, 15, 46

The crackdowns in Turkey, France and South America have resulted in price increases and a definite shortage of heroin at the wholesale and `street' levels on the American east coast.51, 81, 92, 103, 163 In New York the Mafia and their French-Corsican suppliers have had difficulty maintaining adequate supplies of bulk heroin for sale, and the Chinese syndicates (selling Southeast Asian heroin) have at least temporarily assumed a larger share of the wholesale trade.32 Officials of the American B.N.D.D. suggest that French-Corsican refiners and traffickers may soon have to leave France entirely if present enforcement efforts are maintained, and continued police pressure in Latin and South America may force the development of alternate smuggling routes.32

THE SOUTHEAST ASIAN NARCOTICS TRADE

The vast illicit market in China ended when the People's Republic of China was formed in 1949, and existing evidence indicates the problem of opiates use has been eliminated.181 The U.S. Cabinet Committee has stated:

There is no reliable evidence that China has either engaged in or sanctioned the illicit export of opium and its derivatives nor are there any indications of government participation in the opium trade of Southeast Asia and adjacent markets.'

The earlier American, Taiwanese and Soviet allegations that China was consciously flooding the Western world with opium products appear to have been based on political ideology rather than fact.`", 59

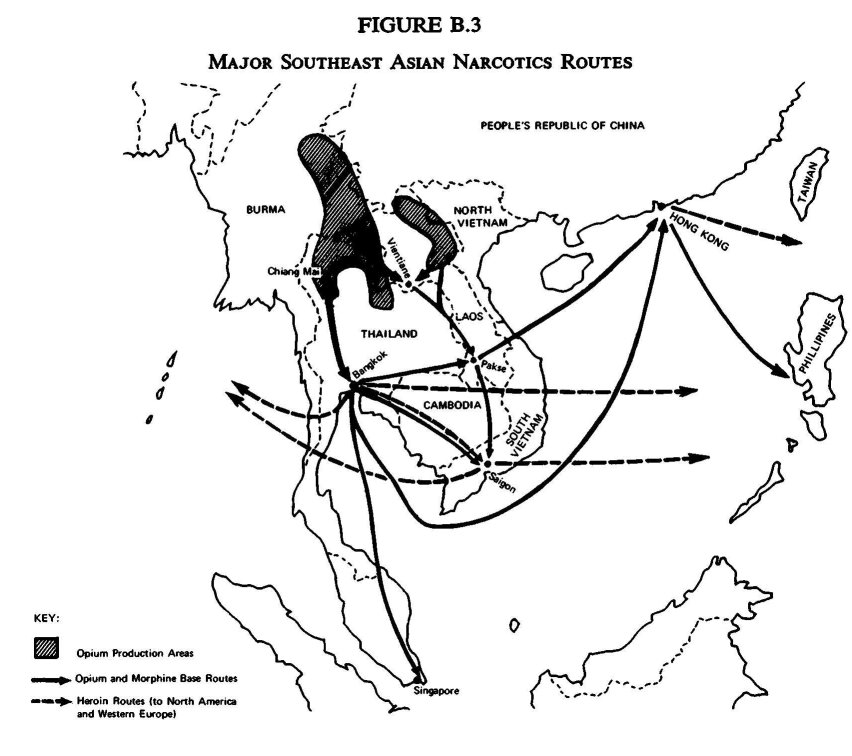

As noted earlier (see "Illicit Production and Consumption"), Southeast Asia is the world's largest source of illicit opium. One hundred of the 700 tons of opium produced in Burma, Laos and Thailand is available for the illicit international trade.'82

Burma

After Chiang Kai-Shek was driven out of Mainland China in 1949, remnants of his Nationalist 93rd Division, the Kuo-Min-Tang (K.M.T.), settled in Northern Burma and Thailand close to the Chinese border.166 One of the K.M.T.'s major sources of income was derived from extorting a heavy toll on local opium producers passing through areas within their control.11, 54, 105, 142, 161, 166 The K.M.T. would then openly smuggle their extorted opium into Thailand.182 The Burmese Government complained to the U.N. about the presence of the K.M.T. in their territory and occasionally attempted to drive them out.113 Burma rejected American economic aid in 1953 to protest the American C.I.A.'s support of this foreign army, *166 and in May 1959, Burmese forces captured and destroyed three K.M.T. opium refineries at Wanton and found an airstrip used to fly in supplies and reinforcements from Taiwan.1°

* American support of the K.M.T. was based on their utility as counter-insurgency and intelligence agents.27, "5, lee, iea

Although the K.M.T. were eventually driven out of Burma in 1960, they resettled in Northern Thailand close to the Burmese border, in the centre of the opium-producing area, and continued to be a major factor in the illicit trade.27 Apparently the K.M.T. are still involved in the smuggling of Burmese opium into Thailand.105. 129, 182 The• .9 pk in June 1971, stated that they had identified 21 opium refineries in the K.M.T. controlled 'Golden Triangle' —the area formed by the borders of Burma, Laos and Thailand."

The American C.I.A. and the Taiwan Government relied on the Civil Air Transport Company, later renamed Air America, to supply the Kuo-MinTang troops in Burma and Thailand and Meo tribesmen in Laos. Both of these latter groups are deeply involved in the opium trade, and it is public knowledge in Southeast Asia that C.A.T., and later Air America, transported supplies and arms in and opium out.27, 71, 141, 142

Thailand

Thailand is significant not only as a major producer and consumer of opium but also as the major conduit through which much of the Burmese opium flows. Thai Police General Phao Sriyanonda, in conjunction with the K.M.T., controlled the illicit narcotics trade in Thailand throughout most of the 1950s and was responsible for Bangkok's development as one of the world's largest illicit morphine and heroin refining centres.21, 76, 105, 188, 193 Phao was ousted after he staged a phony raid on the K.M.T. (all of whom escaped unhurt), confiscated their opium for his own purposes, and then—as deputy minister of finance—wrote himself a $1.2 million reward which he said he gave to a secret informer who then immediately left the coun-

try.18, 105

enterprises, apparently continued the alliance with the K.M.T. in northern Thailand, and bribed a sufficient number of high-ranking government officials to protect themselves from police intervention.78. 1°5

In September 1971, the United States and Thailand signed a Memorandum of Understanding in which both governments pledged to suppress the illicit opium trade.184 However, according to the New York Times, a joint-report of the C.I.A. and U.S. Defence Department, dated February 21, 1972, indicated that no progress could be expected, particularly in Thailand and South Vietnam, due to "the corruption, collusion and indifference" at certain levels of these governments."

Congressional action to cut more than $100 million in foreign aid to Thailand unless the Thais took steps to suppress the illicit narcotics trade," prompted major arrests and seizures against Thai heroin refiners and traffickers.14, 131, 132, 134 The most encouraging sign was a report indicating that the K.M.T. had accepted an offer by the Thai Government to give up opium production and settle in northern Thailand, "in return for cash

The Chinese syndicates assumed control of Phao's abandoned and other benefits"; the K.M.T. apparently handed over 20 tons of raw opium which was publicly burned.134, 152 In July 1972, Nelson G. Gross, the American State Department's senior drug adviser, labelled the earlier pessimistic report of the C.I.A. and U.S. Defence Department as "completely out of date" and indicated that progress was being made in Thailand and elsewhere in Southeast Asia.139 It was later reported by Jack Anderson that the Thai authorities had simply staged the burning of the K.M.T. opium, using cheap fodder mixed with some opium.5 The apparent crackdown in Thailand may simply have forced the K.M.T., the Chinese syndicates, and other participants to be more discreet.

Raw Burmese and Thai opium is transported by the K.M.T. to various collection centres in northern Thailand where much of it is converted into morphine base.", 76 Since the United States troop build-up of the late 1960s these laboratories have also produced heroin 'No. 4%4'52 From northern Thailand the opiates are loaded on trucks or planes for delivery to the clandestine laboratories of Bangkok," or flown into Saigon" and Taiwan.27 Apparently the Chinese syndicates control most of the illicit trade in Bangkok; the French-Corsican syndicates play a smaller role; and there are several relatively minor trafficking operations run by U.S. Vietnam veterans."

The U.S. Cabinet Committee provides a detailed picture of the flow of opiates out of Bangkok's refineries:

Most raw opium and morphine exported to Hong Kong, Malaysia, and Singapore is moved by various fishing trawlers under control of Bangkok traffickers. . . . The same organizations that run the trawlers are believed to handle, at the wholesale level, the growing traffic in No. 4 heroin to international markets. This product is either sold to buyers in Bangkok, who have been mainly US servicemen or US veterans, or delivered directly to buyers in the United States by couriers run by Bangkok dealers themselves."'

The Illicit Opium Trade in French Indo-China: 1945-54

The development of the illicit opiates trade in Laos and South Vietnam is even more complex than that of Burma and Thailand. According to McCoy, the French Colonial Government in Indo-China was forced by world opinion to abolish its official opium monopoly (which had been a major revenue source) after the Second World War.105 The unpopularity in France of the French involvement in Indo-China led to further reductions in the colonial budget. The French intelligence service (SDECE) secretly took over the opium trade, dubbed 'Operation X', to finance their intelligence and counter-insurgency operations against the Pathet Lao and Viet Minh.t In Saigon, the French allowed various elements of the criminal underworld to run the prostitution, gambling, protection and narcotics rackets in return for ridding the city of Viet Minh guerillas and saboteurs. The opium not distributed in Saigon was sold to Chinese and local French-Corsican syndicates. These Chinese syndicates were allied with traffickers of Chinese background throughout Southeast Asia and the Chinese triads in Hong Kong. The French-Corsicans in Saigon smuggled some of their opiates to the French-Corsican heroin refineries of Marseilles.105

* No. 4' is injectable white heroin of at least 90 per cent purity. It is usually contrasted with 'No. 3', a purplish or brownish heroin of much lower purity prepared for administration by smoking. Usage of both of these terms is restricted to Southeast Asia.1 See Figure B.1 above.

t The Pathet Lao and Viet Minh are, respectively, Laotian and Vietnamese communists who are fighting to establish national independence.

After the French withdrawal from Indo-China in 1954, the United States became increasingly involved in Laotian and South Vietnamese political and military affairs. Although unintentional, this American involvement has furthered rather than arrested Southeast Asia's development as a major source for the international opiates markets.

Laos

The American Government has been financing nearly the entire costs of Royal Laotian military activities and, thereby, indirectly subsidizing the traffic in opiates throughout this country.25, 105, 162 General Ouane Rathikoune, the Royal Laotian Minister of Defence until July 1971, had been involved in collecting opium from the K.M.T., protecting—if not controlling—opium and heroin refining laboratories at Ban Houes Sai and elsewhere, using the Royal Laotian Air Force to fly opium products throughout Southeast Asia, and selling the final product to Chinese syndicates, South Vietnamese officials and others.18, 27, 54, 105, 117, 142 Rathikoune's career was abruptly ended when his activities were publicly disclosed by United States Representative Robert Steele.", 117 The Nixon Administration confirmed the broad outline of the Congressman's charges and Rathikoune retired the next day.117 It has been alleged that many of the remaining Laotian Government officials are just as deeply involved in the opium trade as was Rathikoune.54. 78, 105, 142

Since 1959-60, the American Government, through the C.I.A., have also supplied and supported Touby Lyfong and General Van Pao, and their Meo troops known as the Armee Clandestine.87 The U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee noted that the United States budgeted $322 million during the 1971 fiscal year to support these Meos, on whom the C.I.A. relies to keep the Pathet Lao from gaining control of northern Laos.87, 118 The headquarters of Pao's force at Long Cheng (built by the United States as a key C.I.A. base) is one of the major opium collection centres in Laos.27, 154 The bulk of the Meos' opium is flown aboard Southeast Asian military and para-military aircraft to Parkse, Vientiane or Saigon 27, 76, 81, 105

Hughes, in his extensive survey of international heroin trafficking for the Christian Science Monitor, has stated that, ". . . clearly the C.I.A. is cognizant of, if not party to, the extensive movement of opium out of Laos."71 Additional evidence regarding C.I.A. involvement comes from journalist Carl Strock, reporting in the Far Eastern Economic Review:

Over the years eight journalists, including myself, have slipped into Long Cheng and have seen American crews loading T-28 bombers while armed CIA agents chatted with uniformed Thai soldiers and piles of raw opium stood for sale in the market (a kilo for $52).1"

Hughes' and Strock's observations have been echoed by several other sources.2, 3, 44, 105, 135, 141

Prior to the late 1960s there was no local market for heroin No. 4 in Southeast Asia as the indigenous opiate users could not afford this preparation." With the large U.S. troop build-ups, the demand for heroin No. 4 increased and heroin No. 4 refineries were consequently established throughout the Golden Triangle.17, 32, 182 The massive U.S. troop withdrawals in the early 1970s created a surplus of inexpensive heroin No. 4 in Southeast Asia." There is increasing evidence that some of this surplus Laotian heroin is being smuggled into the Western European and North American markets.82, 105, 130 On April 5, 1971 about 17 pounds of pure Laotian heroin were seized at a military base in New Jersey; the package had been sent from Bangkok through the United States military mail.'" The same month, the French Government refused to accept the diplomatic credentials of Prince Sopsaisana, the newly appointed Laotian ambassador to France, because 132 pounds of pure heroin were found in his baggage.". 105 In November 1971, a Philippine diplomat and a Chinese merchant from Bangkok were arrested in New York with about 35 pounds of pure Laotian heroin.133

As a result of American pressure, Laos enacted a law to prohibit the trade, manufacture, and transport of opium after November 15th, 1971. This new law, however, provides for temporary permits for opium smoking and growing by the hill tribes in the opium-growing areas.'" There have been some significant raids and seizures since the enactment of this law, but it is difficult to predict its future impact without knowing if the attitude of government officials, who have for years protected the trade, has in fact changed. It is known that there is considerable hostility to the new law among large sectors of the Laotian people.3°

South Vietnam

South Vietnam does not produce opium but has a large opium-smoking population. Saigon has developed into a centre of heroin distribution for American troops and an international export clearing-house for Southeast Asian opium products." According to several journalists, the French-Corsican syndicates were key figures in the trade and flew into the major collection centres of northern Thailand and Laos to purchase opium. The Corsican fleets of small planes, popularly known as 'Air Opium', would then deliver the opiates to Bangkok and Saigon.27, 91 Part of this opium was converted to morphine base and shipped by the Saigon French-Corsican syndicates to Marseilles for heroin refinement. The role of the French-Corsican air fleets declined as Air America and the Thai, Royal Laotian, and especially the South Vietnamese air forces increaoingly assumed this opium transportation role.27

As in Thailand and Laos, the illicit trade in South Vietnam is a major source of income for some of the country's high-ranking government officials. Charges of opiate-related corruption in South Vietnam have frequently been corroborated by American Government officials. A statement by the United States provost marshall in South Vietnam,152 the 1972 joint report of the American Defence Department and the C.I.A.,64 and testimony presented to the U.S. Congressional Special Subcommittee on Alleged Drug Abuse in the Armed Services,'" reinforce this picture of corruption of South Vietnamese political, police and military officials.* U.S. Representatives Murphy and Steele,'" in their international study of opiates distribution, stated that, "strong action must be taken to stop the heroin traffic in South Vietnam. We are not optimistic that the [Vietnamese] Government is either willing or able to take such action".

South Vietnamese President Thieu launched a well-publicized anti-drug crusade in the summer of 1971. In August of that year President Thieu ordered the death penalty for persons belonging to organized drug-trafficking syndicates and introduced "a tough emergency bill", which made dealing in narcotics a war-time crime, and outlawed opium dens.152, 178 However, the following quotation from a St. Louis Post-Dispatch editorial reflects the skepticism of most observers:

To the unwary, President Nguyen Van Thieu of South Vietnam may seem to have been launching his country on an anti-drug crusade. .. . But reports from Saigon suggest that Thieu's crusade is hardly credible.'

The South Vietnamese police, with the assistance of the American B.N.D.D., have apparently made some arrests and seizures since the enactment of this new laW.163' 185 However, it is presently impossible to determine the full effect of this legislation on opiates distribution in South Vietnam. The withdrawal of American troops resulted in at least a temporary reduction of the price of heroin in South Vietnam to approximately $600 a kilogram in the fall of 1972.32

Hong Kong

Hong Kong is Asia's other major centre of illicit narcotics refinement, consumption and export.59, 77 Several years ago the majority of Southeast Asia's opiates export trade was channelled through Hong Kong, but in recent years Bangkok and Saigon have assumed larger shares of this international trade. According to the U.S. Cabinet Committee, Hong Kong still annually imports ten tons of morphine base for refining (most into heroin No. 3—smoking heroin) and about 50 tons of raw opium for both its 150,000 local users and the export trade.182 Most of Hong Kong's illicit imports arrive from Bangkok aboard Thai fishing vessels, which regularly make deliveries to small Hong Kong junks in international waters or in the nearby territorial waters of the People's Republic of China.", 182

* Non-South Vietnamese governmental officials, including some Canadians, have also been involved in the illicit opiates trade.18' Browning and Garrett report that,

In 1962 ... an opium-smuggling scandal stunned the entire Canadian Parliament. It was in March of that year that Prime Minister Diefenbaker confirmed rumours that nine Canadian members of the immaculate United Nations International Control Commission had been caught carrying opium from Vientiane to the International markets in Saigon on UN planes?'

The Ch'au-chou Chinese syndicates control the illicit narcotics trade in Hong Kong.32' 182 Parallel in structure and organization to the Mafia and French-Corsican syndicates, the Ch'au-chou wield comparable political and economic influence, share a common heritage and dialect, and maintain contact with criminal syndicates of Ch'au-chou descent in the Chinese communities in other parts of the world.32• 77 Independent Ch'au-chou and other Chinese syndicates dominate the collection, refinement and distribution of illicit opiates throughout Southeast Asia.32 The large number of opiate users of Chinese ancestry in Southeast Asia explains the predominance of the various Chinese narcotics syndicates.182

In addition to its own dependent population, Hong Kong supplies the relatively small opiates market in the Philippines and produces some heroin No. 4 for the international export trade.182

Routes and Methods of Smuggling from Southeast Asia to North America

Prior to World War II, the Chinese on the North American west coast dominated our illicit trade with supplies of Southeast Asian opiates smuggled to them by Chinese seamen aboard ocean-going freighters." After the war, however, Southeast Asia became a relatively insignificant source of North American narcotics, and this situation remained unchanged until five or six years ago. Two main factors have historically limited the flow of Southeast Asian opiates into North America: the ready availability of European heroin, and the problem of coordinating Chinese control of supply with Caucasian control of North American demand.

The difficulties encountered by European distributors, coupled with the decline in the availability of inexpensive Middle Eastern opiates, has removed the first barrier,32. 182 while the American presence in South Vietnam and elsewhere in Southeast Asia has removed the second.", "3, 182 As indicated above, American financing has supplied the Thai, Laotian and South Vietnamese Governments with the funds and supplies necessary to modernize the logistics of the Southeast Asian narcotics trade. Although the C.I.A. itself has identified 21 opium refineries in Southeast Asia and implicated the existing governments in their operation,17 the American Administration has yet to revise its military and financial support of these regimes. The Vietnam War has opened up new routes, spawned new syndicates, provided the necessary couriers, and increased the demand for opiates in both South Vietnam and the United States.

There is evidence that heroin is being carried into the United States by Southeast Asian diplomatic personnel or by means of diplomatic pouches.71. 89 The French-Corsican syndicates of Southeast Asia are now likely to supply even larger quantities of Southeast Asian heroin to their Marseilles counterparts. It has been suggested that leading North American Mafiosi with Southeast Asian gambling interests may also now be purchasing pure bulk heroin for import into the United States.105 In addition, small-scale smuggling by the remaining G.I.'s in Southeast Asia and the syndicates composed of exG.I.'s adds to the Southeast Asian flow.", 109

Of greatest concern, however, is potential impact of the Ch'au-chou syndicates' revival of their pre-war system of narcotics smuggling into the North American west coast. The Ch'au-chou in Hong Kong and elsewhere in Southeast Asia are apparently shipping large quantities of heroin to Ch'au-chou contacts in Vancouver, Seattle, Portland, San Francisco and Los Angeles.32 Preliminary results of 'Operation Seawall' (a joint program undertaken by the United States and Canada to stop this flow) indicated that most of the heroin is carried by Chinese sailors of Ch'au-chou origin." In April 1972, the first month of Operation Seawall, eight Chinese seamen were caught bringing in one to four pounds of heroin strapped to their bodies." Once smuggled to west coast Chinese contacts, some of the Southeast Asian heroin is delivered to Chinese trafficking syndicates in New York and other east coast distribution centres. In August 1972, the unofficial mayor of New York's Chinatown and three other Chinese were arrested after they sold 20 pounds of pure Southeast Asian heroin to B.N.D.D. undercover agents.162, 163

According to the American B.N.D.D., the flow of illicit narcotics from Southeast Asia to North America has risen several-fold in the past few years, and further increases are expected.", 181

THE MEXICAN NARCOTICS TRADE

Cultivation

The Chinese of San Francisco first introduced opium poppy cultivation to Mexico shortly after World War II disrupted the flow of opiates from the Orient." There is now illicit opium cultivation throughout the rugged, mountainous, northwestern states of Mexico." As in the Middle East and Southeast Asia, the poppy farmers of Mexico live at a subsistence level; opium represents a substantial portion of their cash income."

Mexico is a relatively small producer of illicit opium with an annual estimated production of 10 to 20 tons.182 Since Mexico is not a significant consumer, almost all of the crop is converted to heroin for export to the United States and Canada. It almost totally dominates the heroin markets of California, Texas and other southwestern states.", 43, 59' 79' 99 Mexican heroin is brownish in colour and only 60 to 70 per cent pure at its source. In Vancouver, it has, in the past, been virtually impossible to sell Mexican heroin unless there was a shortage of the purer European or Asian varieties.147 The unpopularity of Mexican heroin helps to explain why it is far less expensive than even adulterated European heroin of the same purity.

The Organization of the Mexican Trade

The Mexican distribution system is composed of a large number of independent growers, refiners and distributors of varying importance. Even at the upper levels, there is no controlling organization into which the supplies flow or which has the power to dominate the market or set price, quality, or operating standards. A large number of these Mexican dealers run vertically integrated operations controlling the opium crop from the time it is planted until it is sold as heroin. These dealers are likely to own an opium farm, run a conversion laboratory, and maintain a network of agents and couriers to sell and deliver the finished product. Even the biggest Mexican dealers handle much smaller quantities of heroin than the average French-Corsican syndicate.", 99' 128

The best description of these Mexican dealers has been provided by L. J. Redlinger:

Many of the large dealers in Mexico are also in legitimate occupations, most of which pay well. For example, in recent years mayors of cities as well as other politicians have dealt in large quantities of heroin (or opium). Some physicians are also deeply involved in the heroin business as well as businessmen. In many cases, these men finance the building of processing plants to convert the Mexican grown opium into heroin. . . . In addition, they must hire a competent chemist and bribe local officials. If they own the crop, they must pay tenant farmers to care for and harvest the opium. Then they must transport the product to, at least, their side of the border and in many cases all the way to [American import centres].'

The informal organization and lack of central control affects not only law enforcement efforts but also access to the Mexican-grown opium products. Since the market is so diffuse, the arrest of any one dealer or group of dealers will not substantially impede the flow of narcotics. It is virtually impossible for any one syndicate to control the market and charge monopolistic prices. This further explains why the price of heroin at all levels of distribution is far lower in the Mexican market than for similar quantities imported from Europe." The Mexican dealers appear far less concerned about the criminal credentials of their buyers; heroin appears to be available in even small quantities to anyone who can raise the necessary cash.59, 99 For these reasons the Mexican trade is an extremely important source of heroin for the small independent dealers of North America since the distributors of European heroin refuse to deal directly with this level of traffickers.147

Routes and Methods of Smuggling

It is virtually impossible to prevent heroin from being smuggled from Mexico into the United States and Canada. There are scores of relatively safe routes along the 1800-mile Mexican-American border. The popular border crossings are often so swamped with vehicular and pedestrian traffic that a courier's chances of being discovered are minimal, especially if the heroin is carefully concealed, as the drug is almost odourless.

Given the nature of the border, the only way to effectively reduce the flow of Mexican heroin is to eliminate cultivation. The Mexican Government is continually attempting to do this, without apparent success.", 79' 99, 185 The local and federal police are often overworked, afraid, or bribed not to enforce the opium prohibition.58, 73' 33 In some cases, the police and local politicians themselves have been directly involved in the trade.". 126

In 1961, Mexico and the United States exchanged notes by which the United States undertook to supply Mexico with equipment to locate and destroy opium poppy and marijuana fields.22 Although considerable publicity was given to this agreement and subsequent announcements of the destruction of Mexican poppy fields, the flow of heroin has continued unabated.32. 43' 33' 183 In September 1969 the American Government undertook a three-week crash program to search all vehicles and persons crossing the Mexican border into the United States. 'Operation Intercept', as it was called, was undertaken shortly after a U.S. Presidential task force reported that Mexican efforts and resources continued to be inadequate in the face of the drug problem." As a result of Operation Intercept, cars were tied up at the border for six hours, the number of American visitors declined, and unemployment rose dramatically in Mexican border towns which were dependent on tourism. The three-week operation drastically reduced the flow of marijuana, but had a far less significant effect on the heroin traffic.'" The United States and Mexican Governments soon introduced a substitute anti-narcotics campaign titled 'Operation Cooperation', and in August 1971 Mexico announced the seizure of 176 pounds of opium and 116 pounds of heroin since the institution of this program.185

If North American demand rises, there will be more pressure to expand illicit heroin production in Mexico. The development of the Mexican heroin network illustrates the flexibility of the international opiates trade; a crackdown on production in one growing area appears to spawn new sources, leaving the overall situation relatively unchanged.

THE ROLE OF THREE SOURCES IN THE NORTH AMERICAN MARKET: A SUMMARY

The quality, quantity and production costs of heroin differ in each of the three illicit sources. Even more significant is the fact that illegal control of these sources and, therefore, access to them, varies considerably. Each of the sources is independently operated, yet affected by developments in the other two. The exact role of each source in the North American market has become increasingly difficult to determine because of recent increases in illicit demand and the diversification of importation routes.

The Middle East apparently still supplies the majority of the North American market. Much of this heroin is rerouted through Canadian and Latin and South American contacts to the American east coast. Although this market is less tightly controlled than it once was, the smaller North American traffickers are still forced to buy from secondary distributors.

European heroin has always been relatively expensive, especially at the lower levels of distribution, due to the large number of individual dealers who handle it before it reaches the street. The quantity of European heroin entering North America is now expected to continue to decline as a result of the termination of legal Turkish opium cultivation and the improved policing of French refining.

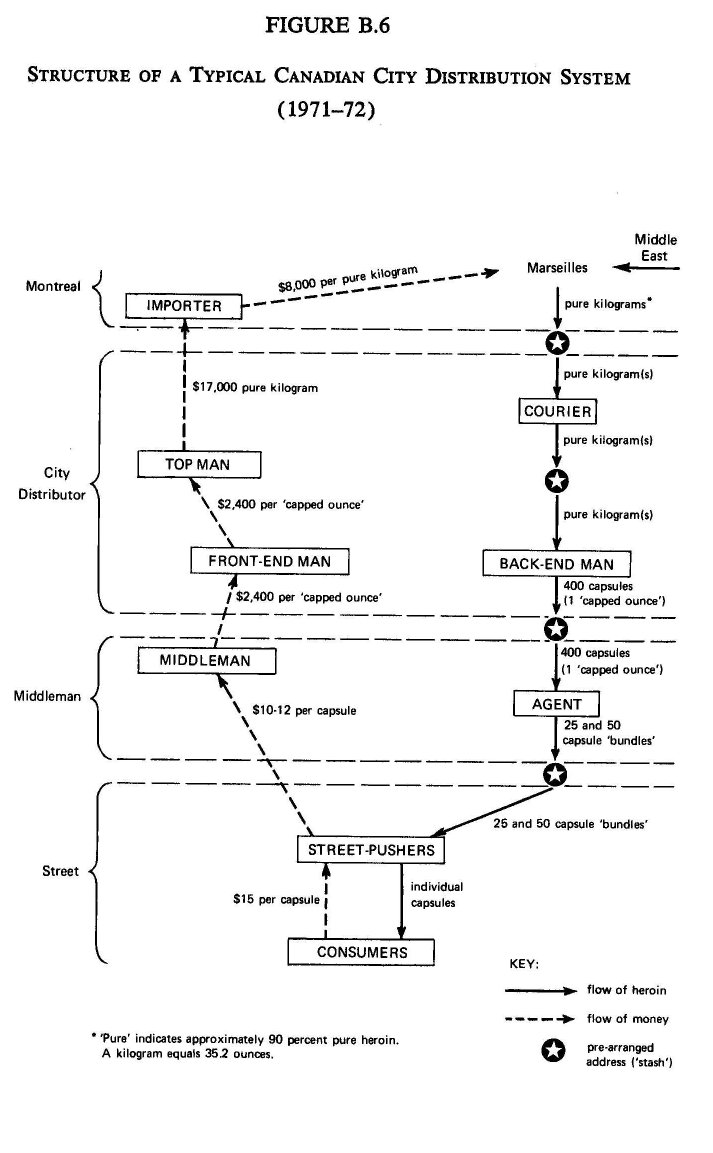

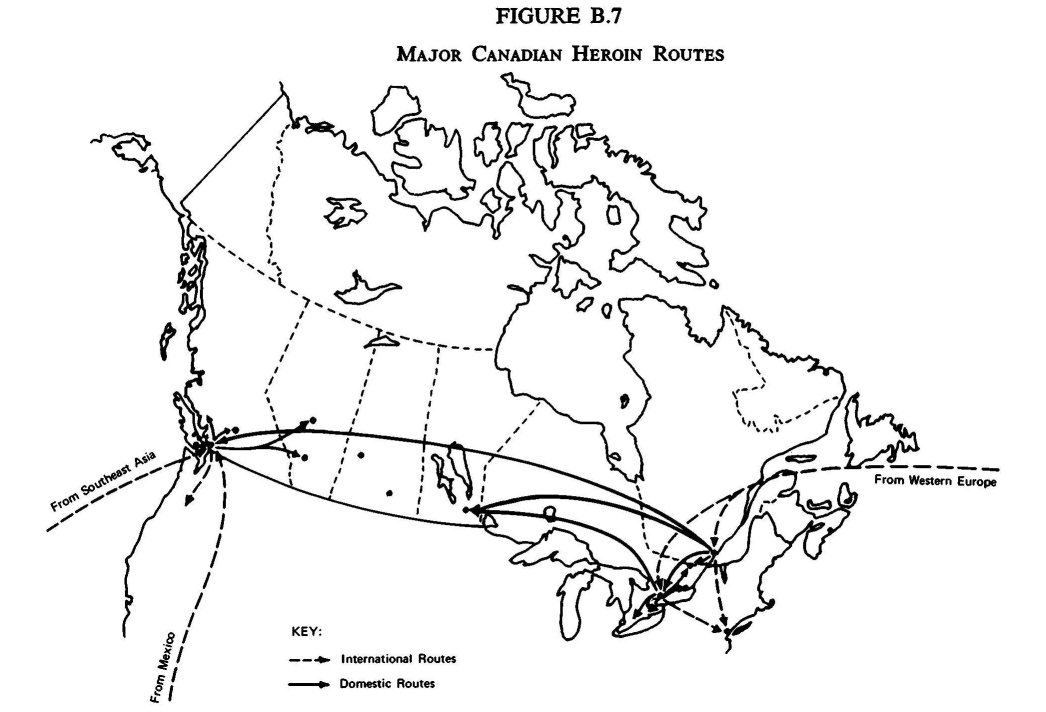

The flow of heroin from Southeast Asia has increased dramatically in the last few years, and this trend is expected to continue. Although Southeast Asian heroin has always been less expensive at its source than that from Mexico or the Middle East, there were substantial problems in coordinating the Asian control of supply with the Caucasian control of demand. This problem has apparently been solved, at least temporarily, by the revival of the Ch'au-chou Chinese pre-war distribution system. In addition, the French-Corsican syndicates, American G.I.'s and ex-G.I.'s, and perhaps the Mafia, have also established means of smuggling Southeast Asian heroin into North America. The reduction in Middle Eastern cultivation and French refining will further encourage the expansion of the Southeast Asian flow. Some officers of the American B.N.D.D. suggest that Southeast Asian heroin will soon dominate the North American market, while other sources simply predict continuing increases.