| - |

Drug Abuse

Part Five

Additional Conclusions and Recommendations of Ian L. Campbell

INTRODUCTION

The major point of difference between my colleagues and myself is the matter of the most appropriate response to the problem of the opiate narcotic user.

Before presenting my conclusions I have reviewed at some length problems concerning the control of the illicit production and distribution of the opiate narcotics and the role of the user of these drugs as a pernicious influence leading others to use them. These subjects are dealt with in Appendices B, C and D. I refer to them here not to suggest that my colleagues are any more optimistic than I about the prospects for control of production and distribution or that they treat less seriously than I the social dangers of the user. We are, I am sure, in full agreement on these matters. I raise them, in summary form, simply to set the context of my recommendations and to underline the factors which have been particularly important in leading me to my conclusions.

THE CONTEXT FOR SOCIAL POLICY

THE RAPID INCREASE IN THE USE OF AND ADDICTION TO THE OPIATE NARCOTICS

Notwithstanding the real inadequacies in our statistics it is clear that there have been recent alarming increases in the non-medical use of the opiate narcotics, particularly heroin and methadone. Not only has the population of users and addicts increased, but it appears to be growing at an accelerating rate. For instance, the number of 'street addicts' reported by D.N.C. rose in 1968 by 123, in 1969 by 275, in 1970 by 918, in 1971 by 1,728 and in 1972 by 2,460. The actual number of new users was no doubt very much larger in each year. There seems little reason to believe, on the basis of either Canadian or American data and experience, that the problem has peaked. Moreover, rather large populations at high risk of beginning opiate narcotic use are present in Canada.

It is evident that over an extended period of time increases in heroin use often come in waves. For example, in Chicago there was a marked increase in use immediately following the Second World War. This particular epidemic reached its peak in 1949. There was then a decline in the numbers beginning heroin use during the 1950s and an increase again in the later 1960s. This pattern has been observed in a number of other cities. The phenomenon is mentioned here because of the risk that any drop in the numbers of new users appearing in the statistics of a particular year might be too readily taken as an indication that the problems of opiate narcotic use are coming under control.

It must also be pointed out that a study of national or even provincial statistics can be misleading. For instance, an increase of five hundred users in British Columbia might mean that a steady increase in use had occurred in a localized part of Vancouver. However, it might also mean that heroin use had entered fifteen communities where it had not been present before and had spread explosively within these communities with a high probability of becoming endemic in them. The second possibility would perhaps be far more serious than the first because of the potential for a spread of use to neighbouring communities and because the endemic presence of opiate narcotic use provides a base for a rapid increase in use and dependency at a later date.

PRINCIPAL CAUSES OF THE INCREASE OF OPIATE NARCOTIC USE

It is clear that we lack any full understanding of the causes of opiate narcotic use. Indeed what may be said accurately of the causal pattern in one area may not apply in another and causal patterns change through time. The same problem exists in generalizing about drug-using careers. Details of career descriptions may be wholly valid only for a particular locale at a particular time.

However, two important, obviously valid generalizations about the necessary conditions for a spread of opiate narcotic use are possible. Use only spreads when the drugs are available and when there is a population of users present as a pernicious influence. A third generalization can be made with only slightly less confidence; the new opiate narcotic user is more likely to influence non-users to experiment with these drugs than is the person with a long-standing pattern of use and addiction.

The Availability of Opiate Narcotics

In the nature of things the ability of the Government to control the entry of opiate narcotics into Canada will be very largely dependent on the ability of the American Government to control the general flow of these drugs into North America and its ability to influence other governments to inhibit the growth of the opium poppy, the production of opium derivatives or the production of synthetic narcotics and the movement of drugs within and across their borders.

The Americans have achieved increasing success in a number of their policies. Their influence has reduced the production of opium in Turkey. At least partially as a result of American pressure, the Government of France is now taking effective steps to attack the manufacture of heroin. The United States appears to have gained an increased cooperation from some South American governments in making the shipment of drugs through South America more difficult and in breaking up some trafficking rings.

However, even the total elimination of poppy growing in Turkey will not now produce any significant shortage of raw opium. Some of the opium that has come out of Turkey in recent years has not been grown in that country. There are millions of acres of land available in other countries which are suitable for poppy cultivation, and much of that land is within the borders of states not clearly subject to American influence or indeed under the effective control of the national government concerned. In some regions, such as South East Asia, poppy acreage can presumably be expanded. In other regions, for example South America, there is little reason to think that poppy cultivation cannot be introduced. Consequently, I cannot be confident that in the foreseeable future the American posture of curtailing poppy cultivation will have much more than a disruptive influence on the production of raw opium.

The new enforcement activities of the French police in moving against the manufacture of heroin have had a disruptive effect on the flow of the drug from Europe to North America. However, it would be naive, on the basis of existing evidence, to think that this will be more than a relatively short run dislocation of production. It is not difficult to think of countries to which European manufacturing operations could be moved either in Europe or North Africa. There are a number of European states that do not have strong anti-drug police operations and there are a number which cannot be assumed to be sympathetic to the American case or receptive to American pressure. It is also noteworthy that the impact of the French moves was blunted by an increased flow of heroin to North America from other sources —notably South East Asia. In other words, the world supply of heroin seems more than adequate to compensate for even a major blow to production potential. I would expect that the lost French production will be replaced in Europe or North Africa very quickly indeed.

It must also be pointed out that the total eradication of the opium poppy would not eliminate the availability of narcotics in North America because of the substitutes for opium and its derivatives that are or could be made available. First, there are drugs such as methadone and pethidine (Demerol®) which are wholly synthetic. The processes by which they are manufactured are available in the chemistry and pharmacology journals. The raw materials required for the production of these synthetics are readily available and not potentially subject to rigorous international or national control. While skilled chemists are needed to supervise or carry out production, there is no reason to think that the billion dollar narcotics industry would have difficulty in buying whatever skill are needed.

Unfortunately, natural or semi-synthetic narcotics can also be produced from poppies other than the opium poppy (Popover somniferum). Thebaine is found in the opium poppy but also in many other forms of poppy that do not yield opium. As is pointed out elsewhere in this report, some thebaine derivatives have morphine-like effects and have a potency of up to more than 1,000 times that of morphine or heroin. Some of these derivatives are in commercial production. Leaks of these drugs from legitimate manufacturers are bound to occur in time. But far more important, there is a source of narcotics apart from the opium poppy that can be exploited.

For these reasons, and others, I think it would be less than prudent to assume any long-term decrease in the international availability of heroin or equivalent drugs. Indeed a persuasive case can be argued that we should assume an overall increase in production or productive potential.

The international heroin distribution system has grown rapidly. There has been a marked proliferation of routes and networks and of smuggling techniques. Consequently, the overall impact of arrests for trafficking is reduced. Profits are more than high enough to ensure that there will be no problems of recruitment. The world heroin supply system, while not monolithic, has demonstrated that it has the reserves and the flexibility to respond quickly and effectively to any injury that has so far been inflicted. There is no evidence at hand to suggest that this will not continue to be the case. International officials concerned with the enforcement of drug laws admit that only a very small proportion of narcotics in transit can be intercepted.

Reluctantly I am forced to the conclusion that our best efforts to control opiate narcotic production and international trafficking can do little more than be a costly nuisance to the international market. I do not conclude that these efforts should be reduced, but only that it could be dangerously naive to expect significant results in terms of reducing the long-term availability of illicit narcotics in North America.

At the national s ci there are further reasons to feel pessimism about our ability to control availability of opiate narcotics. One of the most important of these is the enormous growth in the number of drug distribution systems both for heroin and for other drugs. We already have evidence in Canada of individuals who have been multi-drug dealers now handling heroin. Similarly in the United States there seems to have been an increase in the number of dealers, at various distribution levels, who handle a variety of drugs including heroin. We also have illicit drug distribution operations in far more centres than ever before which are capable of making heroin available to almost any city, town or village in Canada.

It therefore seems virtually certain that one of the two necessary conditions for a continued increase in the use of opiate narcotics is and will continue to be present in a form that will facilitate increased use in all parts of the country.

Ordinarily there must be the presence of a supply of opiate narcotics and the presence of a population of users for there to be a significant increase in use. However, there are exceptions. The most important exceptions appear to be instances where either some dealer moves to 'push' the drug, that is to say, actively sell the drug to non-users, or where there is a population of non-users who are curious about heroin and anxious to experiment with it. Overall the 'pusher' appears to have played a less important role than the public has assumed. A major reason has been the danger of detection and arrest to which the 'pusher' is exposed in approaching anyone other than a known user. However, this danger is to some extent attenuated where there is a population of known illicit drug users and we have had reports of heroin being introduced to the illicit drug-using population by dealers. We have also had reports of an increasing curiosity about heroin that has acted to create a demand. This has been found, for instance, among some populations of promiscuous, multi-drug using teenagers. Consequently, the fact of a steady availability of heroin in an increasing number of centres will in itself assure some increase in heroin use and hence of addiction. It is, of course, difficult to estimate the extent of the increase which will result.

The Presence of Opiate Narcotic Users

The evidence available indicates clearly that the overwhelming majority of those who use heroin began their use subsequent to and very largely as a consequence of association with users. Whether we designate the users as being infectious or contagious or a pernicious influence is not of great importance in this context. The fact of the matter is that their presence contributes to the use of opiate narcotics by those who have not previously used these drugs.

The role of opiate narcotic users as a pernicious influence fostering the spread of use of these drugs is discussed in Appendices C and D. As we report there, research has been consistent in finding that almost invariably the new user is introduced to opiate narcotic use in a small group setting of friends. Often the new user's presence is fortuitous although, clearly, some curiosity about the drugs and a readiness to experiment must usually exist. It appears that the experienced user is often admired as a person or for his life style by the beginner. There are certainly instances when group pressure is applied by users, and particularly new users, to encourage non-users to experiment.

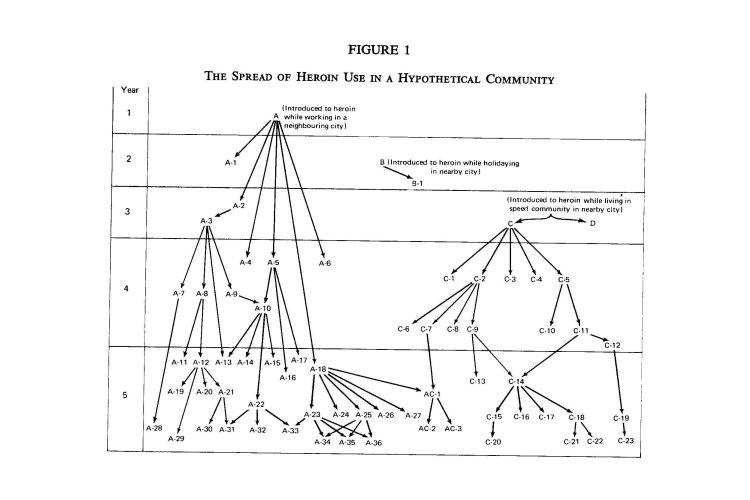

It seems that typically heroin use begins in a community or neighbourhood by the return of one or two individuals who have begun use elsewhere. These foster interest in the drug and introduce use to a few friends. These friends in turn introduce others or at least play a role of maintaining interest by their own example and presence and often by facilitating local access to opiate narcotics. At first use seems to spread slowly, but as the number of users grows there is the risk of an explosive increase in use. Studies in the United Kingdom of the spread of heroin use that have now been replicated in the United States have found a pattern of heroin use initiation that is represented in Figure 1 below.

The evidence overwhelmingly supports the opinion that the use of heroin is spread through contact with those who actively use the drug. Indeed, the evidence is conclusive enough to probably warrant a generalization that the presence of opiate narcotic users is almost always a necessary condition for a significant increase in the use of these drugs.

Among users it is also clear that the new user is most apt to be the contagious or pernicious agent. The user who has not yet become addicted or who does not recognize the fact of his addiction seems more prone to counsel others that heroin can be used 'wisely' with little or no risk of addiction and to hold himself up as living proof of this fact. Again, there is much in the research literature to support this position. For example, Hughes and Crawford in their Chicago study report,

... the disorder tends to be most contagious during the early stages, i.e., it is spread by new users and the newly addicted. This suggests that new outbreaks must be identified early.

INCREASE IN THE SIZE OF THE POPULATION AT RISK TO OPIATE NARCOTIC USE

The sharp increase in the rates of opiate narcotic use and addiction are in themselves indicators of the increase in the size of the population that has been at risk to the use of these drugs. There is, however, no reason to think that their use will not continue to spread in Canada for some time to come. There is evidence appearing that the use of heroin is levelling off in the United States. But it is levelling at a point that involves a much higher proportion of the total population than has as yet become involved here. Even if we note that much of the heroin use in the United States has been in 'ghetto' populations and that comparable populations do not exist to any great extent in Canada, we are still well below the levels of American non-ghetto use. Given time, Canada's rates of drug use tend to move towards those reached in the U.S. Hence, it would not appear prudent to expect that the spread of heroin use is about to level in Canada.

There are certain populations that appear to be particularly at risk. Perhaps the most obvious are the regular, high-dose, intravenous amphetamine users — the 'speed freaks'. As noted elsewhere in this report, the 'speed freak' population has not decreased markedly although it has dispersed and become far less visible than it was in the summer of 1970. Much of this population is apparently replaced approximately every two years since that seems to be the maximum period for amphetamine use for most individuals. It would appear that many of these persons have become involved in the use of heroin.

There have been a steady series of reports of curiosity about heroin among young, promiscuous multi-drug users. While there may be some tapering off of the size of this population, it remains significant and constantly draws new recruits. We know far too little about the epidemiology of nonmedical drug use to predict with any degree of confidence that it will not blossom again or at least maintain roughly present levels. These young people, because of their naivety or lack of concern with the consequences of their drug use, are at high risk to heroin use and dependence.

During the past two years there have been reports of heroin use among populations that do not have a history of illicit non-medical drug use. In particular this has been noted among the children of Italian immigrants in Toronto. In the past such populations have been at risk to many forms of delinquent and deviant behaviour. There seems no reason to be sanguine about the possibility of wider opiate narcotic use among such people—and certainly their numbers have increased in Canada.

In summary then, there exists in Canada a number of populations that appear at particular risk to a further spread of heroin use.

THE NATURE OF THE OPIATE NARCOTICS

The psychological effects of the opiate narcotics and the consequences and risks of their use are set out fully in Appendix A. In this context it is only necessary for me to note the particular qualities of these drugs that lead me to believe that their use should be treated in law rather more severely than that of other drugs in current non-medical use.

Many attempts have been made to rank drugs in an order of relative potential for harm. If a single criterion of harm is accepted it is perhaps not difficult to construct such an order. For example, if we accept as the focus of our concern the probability of continuing general physiological deterioration as a direct result of the use of the drug, then alcohol and tobacco must be taken as among the most dangerous drugs in current non-medical use, and heroin and the other opiate narcotics as among the least dangerous. If we make the criterion the probability of continuing general physiological deterioration as an indirect consequence of dependent use of a drug, then alcohol and the opiate-narcotics would stand together as among our most dangerous drugs. If we take short-run physiological deterioration as a direct and indirect consequence of the use of a drug, then the amphetamines would probably stand as our most dangerous drug, the opiate narcotics and alcohol would occupy a much lower place and tobacco a lower place still. If we focus on probable use as a means of suicide then the barbiturates have probably the greatest potential for harm and the opiate narcotics and alcohol are relatively safe. If we give a high priority in determining potential for harm to such criteria as the risk of accidental death associated with use or the risk of virtually incurable drug dependency developing quickly as a result of use for even a short period of time, then the opiate narcotics are certainly among the most dangerous, if not the most dangerous. If a high priority is given to a drug's capacity to produce socially undesirable behaviour such as theft or prostitution, then the opiate narcotics are among the most dangerous drugs in the present North American social context. The amphetamines and alcohol, on the other hand, are ordinarily far more prone to lead to crimes of violence. If we are concerned with the potential of drug use to profoundly alter personality and character, and with the consequences of such changes for the user and those close to him, then the opiate narcotics are among our most dangerous drugs. Overall, I doubt that a single, meaningful rank order of the potential for harm of drugs in current non-medical use can be created. It is probably wiser to point to particular dangers associated with the use of a drug or family of drugs.

In coming to my conclusions about appropriate social policy with respect to the opiate narcotics, I have given weight to the following facts.

The opiate narcotics are virtually unique in their capacity to produce a state of severe dependence quickly and insidiously. Once established, opiate narcotic dependency can be managed but for all practical purposes, at this time, is virtually incurable.

It is obviously true that dependency is not an inevitable consequence of the experimental or occasional use of opiate narcotics. There are some few individuals who have used these drugs for years and have not become dependent. Virtually all addicts believed, when they began use, that notwithstanding the dangers of addiction they could avoid this consequence. Virtually all believed that their use was still 'under control' when they in fact had become dependent. While data is not available from which it is possible to estimate the proportion of those who ever used these drugs non-medically who later became addicted, it can be said that the proportion is high. All who use these drugs non-medically must be considered to be at significant risk of becoming dependent.

Those who became dependent on the opiate narcotics have as a result become significantly diminished in their capacity to act as free men—more than is the case with virtually any other form of dependence. The greatest part of their loss of freedom comes from the simple necessity of devoting a large proportion of their time to acquiring (usually illegally) the money to buy drugs. Thus the range of choices open to them vocationally, intellectually, recreationally, socially and geographically is severely curtailed. This loss of freedom to determine the course of one's own life and the use of one's own potential is surely a loss that renders them effectively less human than they would otherwise be.

The nature of opiate narcotic dependence in the present social context, and in any social context which I care to contemplate, virtually ensures that the addict will maintain and increase the criminality that usually precedes his addiction or will develop criminal habits. Insofar as most addicts were criminals before they became addicted it is not proper to assert that the whole of their criminality is a consequence and a cost to be attributed to their drug use. But it is clear that the amount of their predatory crime increases subsequent to addiction. An important result is the further loss of freedom that follows from conviction for these crimes.

Moreover, their criminality, typically in the form of drug peddling, burglary, shoplifting and other forms of boosting, pickpocketing and panhandling and of prostitution in the case of females is a heavy cost to society. The fact that as much as half their illicit income may come from selling opiate narcotics presents a serious problem in facilitating use among others.

While it is true that the total cost of crime attributable to alcohol exceeds that attributable to the opiate narcotics, it is clear that the probability of an opiate narcotic-dependent person supporting himself by crime is far greater than in the case of dependency on any other drug, including alcohol.

The life style that is the virtually inevitable consequence of illicit opiate narcotic dependency has other costs. Most addicts suffer from malnutrition and are particularly subject to diseases associated with malnutrition and lack of hygiene. These consequences probably follow mainly from the life style of the addict but can certainly be attributed in part to the psychological effects of the drugs.

I am also concerned with the impact of the adoption of their life style on the relatives and friends of the addict. I find it hard to conceive of more dreadful information than the news that one's child has become addicted to these drugs. I suspect that perhaps unconsciously much of our fear of the opiate narcotics springs from the knowledge or well-founded suspicion that dependency on these drugs profoundly and irrevocably changes the person—they become different not only in life style but in personality and spirit, their reactions can no longer be predicted by those who have been close to them, their promise and whatever was hoped for them is gone, and their future is at best bleak.

Some of these undesirable consequences of addiction could no doubt be prevented if opiate narcotics were made readily and cheaply available to the user and the addict without stringent controls and monitoring. But in view of the marked increase in use and hence addiction that would certainly follow, the costs would clearly far outweigh any possible benefits.

More than other drugs used non-medically, the use of opiate narcotics is likely to produce accidental sudden death. While most deaths associated with drug use by addicts are clearly not due to a simple heroin overdose, as is generally believed, the fact is that a large number of heroin users die suddenly while injecting this drug.

THE OBJECTIVES OF SOCIAL POLICY

THE PRIORITIES OF SOCIAL POLICY

In my opinion the proper order of priorities in developing social policy with respect to the opiate narcotics user is:

1) The prevention, as much as is possible, of the further spread of opiate narcotic use and addiction.

2) The treatment of the user or addict to render him less socially dangerous.

3) The treatment of the user or addict for the purpose of improving his chances of being a useful member of the community and of improving the quality of his life.

Since, in virtually all cases, the presence of opiate narcotic users is a necessary condition for the spread of use, it follows that isolating users or otherwise reducing their capacity to influence perniciously and assist others to use these drugs is a necessary step and probably the most important single step that can be taken by a country such as Canada in the prevention of an increase in opiate narcotic use and addiction.

Clearly, short of placing all users in indefinite quarantine, there are no means of ensuring that they will not be a pernicious and contagious influence. However, if they could be officially identified and if their drug use could then be eliminated or controlled so that they could no longer stand as directly observable models of free opiate narcotic use, and incidentally a source of supply to the prospective user, the danger would be significantly lessened. If they could be prevented from presenting themselves as living examples of the fact that opiate narcotics can be used without serious consequences, the danger would also lessen.

It is obvious that these ends can only be achieved by making it highly probable that those who use the opiate narcotics can be brought to official attention in a way that renders them subject to control, and by having the means of monitoring and controlling their behaviour.

I believe that these ends can be achieved, that this can be done without recourse to police state methods, with adequate safeguards to the innocent and in a manner that serves the long-run best interests of the opiate narcotic user.

However, unless the steps that I propose are implemented in the near future I am not sure that they provide a practical solution to the problem. The present population of heroin and methadone users is of a size and geographic distribution that makes it conceivable to exert a close control over its members, albeit with a heavy expenditure of resources. However, if the numbers involved continue to increase at present rates, or even rather more slowly, and if we approach American rates of use or if the present population or a larger one disperses geographically, then the outlook for effective action would be far more bleak and the price far higher.

THE EFFICACY OF EXISTING LAWS AS A DEVICE OF CONTROL

The existing laws relating to the possession of opiate narcotics seem to me to lack the potential to ensure early official detection of opiate narcotic use and to lack the potential to exert control over a significant proportion of users and addicts. The necessity of proving possession presents the police with a virtually insuperable problem in bringing most users before the courts. As has been pointed out elsewhere in this report, many users have the drug in their possession for a very short time indeed—often for only a few moments in the course of a day. Unless they are apprehended during those moments no evidence is available to the police. Moreover, when the drug is in the user's possession it is frequently carried in the mouth and is swallowed at the first sign of police intervention. This fact necessitates the rough action that the police take towards users in attempting to make arrests and adds greatly to the difficulty of securing evidence.

The arrest and conviction statistics presented in this report, if compared to the estimates of use, provide convincing testimony of the inadequacy of the present laws as a device for detecting and controlling the opiate narcotic user. It is likely that fewer than four per cent of the addicts in Canada are currently being convicted each year and that this number may be fewer than one per cent of all who are addicts and occasional and experimental users.

RECOMMENDATIONS WITH REFERENCE TO THE LAW RESPECTING THE OPIATE NARCOTIC USER

So long as the law only prohibits the unauthorized possession of opiate narcotics, I can see no way in which it can become an effective device to control the opiate narcotic user and hence a really effective device to curtail the further spread of the use of these drugs. This would remain true even if the police were granted very large reinforcements. Moreover, as use spreads, it seems to me that the relative effectiveness of the police is bound to decline.

Consequently, I recommend that the law be amended to make the unauthorized use as well as the unauthorized possession of opiate narcotics an offence. The unauthorized possession of opiate narcotics or the presence of an opiate narcotic in the urine, blood or other body fluid without lawful excuse should be taken as proof of opiate narcotic use. To enforce adequately such legislation, it would be necessary to authorize the police to require those whom they believe, on reasonable and probable grounds, to be using these drugs to submit a sample of urine, blood or other body fluid for analysis.* Continuing association with known opiate narcotic users, the clear appearance of being under the influence of an opiate narcotic (on the nod) or the otherwise inexplicable presence of injection marks visible on the body would certainly be reasonable and probable grounds to presume the use of opiate narcotics.

Clearly a number of safeguards would be required in such legislation. I would strongly recommend that at least the following be included:

a) A part of any sample taken should be returned to the donor in a sealed container for use by the defence if a charge is laid and the result of the analysis is submitted as evidence.

b) Those required to give a sample should be given, on request and before the sample is taken, a written statement of the reasonable and probable grounds on which the police are acting.

c) The police should be required to submit the details of their use of such authority, including a statement of the grounds on which it was used, to a judicial body for a regular and public review.

Those whose urine, blood or other body fluid is found to contain an opiate narcotic should be charged with the unauthorized use of these drugs. Those arraigned on this charge should, in all cases, be remanded in custody for one week for the purpose of determining whether or not they are dependent on the opiate narcotics.

Those subsequently found guilty of the unauthorized use of opiate narcotics but who are not dependent on these drugs should on the first and second conviction receive a one- to three-year sentence with the possibility of immediate release on parole at the discretion of the court, after appropriate consultation with the Parole Board, with the following conditions at least:*

1) That they refrain absolutely from the unauthorized use of opiate narcotics, cocaine and amphetamines.

2) That they submit urine, blood or other fluid samples for analysis as often as necessary to determine any opiate narcotic use for a period of six months and thereafter as required during the period of probation.t

3) That they refrain from association with opiate narcotic users and others as required.

4) That they accept counselling or other appropriate care as required.

Those who are unwilling to sign a statement accepting the terms of parole should not be released from custody.

Those responsible for the supervision of parole must be given reasonable authority to excuse occasional breaches of the terms. However, those brought before the Parole Board for parole violation should be liable to be imprisoned for the balance of the period of their sentences.

Conviction a third or subsequent time should render the offender liable to imprisonment for a period of two to five years. If the offender is subsequently released on parole, terms similar to the terms above should be applied.

Those found guilty of the unauthorized use of opiate narcotics and who are shown to be dependentt on these drugs should on the first and second conviction receive a three- to ten-year sentence with the possibility of immediate release on parole at the discretion of the court, following appropriate consultation with the Parole Board, with the following conditions, at least§

1) That they refrain absolutely from the use of unauthorized opiate narcotics, cocaine and amphetamines.

2) That they submit urine, blood or other body fluid samples for analysis as often as necessary to find any opiate narcotic use for a period of two years and thereafter as required during the period of their probation.*

3) That they accept counselling and treatment as required by those responsible for their probation.

4) That, if after other treatment approaches have been tried for a reasonable period and they are unable to remain drug-free, they accept high-dose methadone maintenance indefinitely.

It has frequently been found that continued association with opiate narcotic users is a major barrier to the successful rehabilitation of those who are opiate narcotic dependents. Consequently, the courts and parole officers should have the authority to require the offender to change his place of residence.

In the case of those with longstanding or severe addiction, the court should have authority to impose high-dose methadone maintenance as an initial condition of parole. Unwillingness to accept the terms of parole or violation of the terms of parole, when brought to the attention of the Parole Board, should render the offender liable to imprisonment for the balance of his sentence.

Those found guilty of unauthorized opiate narcotic use a third or subsequent time and who are found to be dependent on these drugs should receive a sentence to indefinite imprisonment with the possibility of parole on conditions similar to the conditions of parole noted above.

Wherever possible a separation should be made between the personnel responsible for parole supervision and those responsible for the treatment of persons under sentence, although there should be cooperation and consultation between them and both should come under a single agency. If treatment personnel are made responsible for the collection and analysis of urine or blood samples, the results of these tests, if they show the presence of a prohibited drug, should be automatically reported to the parole authorities. The supervision of opiate narcotic users requires specialized knowledge and experience. Therefore personnel should be specially selected and trained for this work.

Those imprisoned for the use or possession of opiate narcotics should, whenever possible, be confined apart from other prisoners, preferably in separate institutions, and should be further segregated according to the extent of their involvement in and commitment to the opiate narcotic-using culture. Clearly, a basic purpose of their incarceration should be quarantine.

Provision should be made in the case of those charged with the use of opiate narcotics to conduct the trial in camera at the request of the accused and at the discretion of the court. The purpose of this provision is to keep secret the identity of the accused and hence to facilitate rehabilitation, particularly in the case of those who appear to have been experimental users of the opiate narcotics.

Those convicted of unauthorized opiate narcotic use who remain absolutely drug-free while on parole or otherwise at large during a period equal to the length of their sentence should be authorized to withhold the fact of their arrest and conviction in such matters as employment applications. If at some time during the course of the sentence an opiate narcotic or other illicit drug is found in a urine or other body fluid sample, then an opportunity should be provided for them to continue submitting samples beyond the end of their sentence to establish a drug-free period equal to the length of the sentence and to thus qualify for the benefits of these provisions.

My recommendations require the enactment of special parole provisions for opiate narcotic offenders. At the present time the courts in Canada play no role in the decision to release a prisoner on parole. This decision, except in cases of murder, is exclusively under the jurisdiction of the Natinnal Parole Board. While the Board may release an offender at any time, it extremely unusual for it to do so until a significant portion of the sentence has been served in prison. I see no reason to require the imprisonment of all found guilty of opiate narcotic use; however, I am convinced that all require a prolonged period of supervision and control. Consequently, my recommendation requires that the courts be granted authority to grant parole at the time of sentencing. An alternative approach would have been to recommend the use of suspended sentence and probation. I have rejected this alternative for a number of reasons. For instance, a suspension of sentencing can only be granted when an offence carries no minimum sentence, and I am strongly of the opinion that a minimum sentence is absolutely required in dealing with opiate narcotic users.

The efficacy of my proposals is clearly dependent upon the ability of the police to identify a significant proportion of opiate narcotic users and to secure convictions against them. The development of new techniques for the analysis of body fluids which will detect the presence of narcotics many hours after use, and potentially several days after use, gives reason for confidence on the latter point. The identification of users is a different matter. Six or seven years ago the police knew the identity of a very high proportion of heroin users. Since they were concentrated in distinct areas of a very few cities their task was relatively easy. Today this population has not only grown but has dispersed to many communities, principally in British Columbia, Alberta and Ontario. However, both Canadian and American evidence indicates that within a given community the opiate narcotic users tend to cluster in 'copping areas' which are not difficult to find. While this population may not be as visible as was that of the speed freaks

in 1970, it is very much more visible than most other illicit drug-using populations. In the case of addicts the necessity of regular and frequent purchases helps to maintain visibility. Occasional and experimental users, coming as they do largely from the ranks of the speed users or the promiscuous multi-drug users, also should not be very difficult to detect, granted adequate police personnel and special undercover operations.

It will no doubt be argued that these recommendations are extremely severe. This is obviously true. But I regard the opiate narcotic user as posing a potentially grave danger to society. His presence is often an essential condition for the spread of opiate narcotic use. New users pose a special threat because of the greater risk that they will proselytize and make statements minimizing the risk of opiate narcotic use. Their presence as opiate narcotic users clearly constitutes a real threat to the health, welfare and operative freedom of others. Unless a very high proportion of them are detected and brought under rigorous control, as regards their drug use, I see the real probability of a further significant spread in opiate narcotic use.

I believe that my recommendations provide the opportunity for those convicted of opiate narcotic use to limit drastically the impact of their sentence on their own freedom. So long as they are prepared to refrain from the unauthorized use of opiate narcotics, cocaine and the amphetamines they can be at liberty to lead perfectly normal lives. The limitation of freedom imposed by the requirement to submit urine, blood or other fluid samples is not in itself a severe penalty or hardship and is certainly in their best interests. To be an effective check on unauthorized drug use, it is necessary that the sample be always provided in the presence of a witness. But there should be no great difficulty in making arrangements for the sample to be taken close to the offender's residence or place of work at a hospital, pharmacy, physician's office or other appropriate site.

It may be argued that requiring urine, blood or other fluid samples from those suspected of unauthorized opiate narcotic use is a violation of proper civil liberty or forces an individual to provide evidence against himself. However, we have accepted a strikingly similar precedent with the compulsory use of breathalyzers for the detection of alcohol intoxication. In the case of a urine, blood or other fluid sample, it should be readily possible to provide the suspect with a part of the sample in a sealed container to prevent any risk of evidence being fabricated and to allow for independent analysis. This safeguard is not as yet possible when breath samples are taken.

It is clear that the implementation of my recommendations would be costly. Some large number of additional police will be required as well as specially trained parole and probation officers. However, great as these costs would be, I am convinced that they would, in the long run, be far less than the direct and indirect costs of a further significant increase in use.

I would further submit that the level of control of the opiate narcotic user that my recommendations could provide would strike a very severe blow at the illicit opiate narcotic distribution system by drastically reducing demand. The result would probably be a lessening of the availability of heroin. This, in itself, could contribute further to the prevention of a further spread of use.

It has been pointed out in this report and in our Interim Report that the existing laws compel the police to deal with those suspected of opiate narcotic possession in a rather rough manner that typically involves breaking down doors and 'throttling' suspects to prevent the loss of necessary evidence. While the necessity of such actions cannot be denied, it must be regretted. The change from a possession of narcotics to a use of narcotics emphasis would eliminate the need for virtually all such police acts since surprise would no longer be of the essence except in cases of suspected trafficking.

I believe that my recommendations would, if implemented, have an immediate deterrent effect of reducing the amount of opiate narcotic use among non-addicts. This reduction would in all probability be significant enough that it should be taken into account in a calculation of the costs of implementation or of feasibility. It is my opinion that my recommendations can be applied with a high probability of success to a population of users of opiate narcotics of the size which we estimate with its present pattern of distribution. I would be far less sanguine about their probable success if there is a marked increase in the size of that population and a more general geographic distribution of use. It is much more difficult to conceive of control measures that would be effective and acceptable in a free society if use were to reach the levels found in the United States.

My proposals rest on the assumption that, given adequate reinforcements, the police would be able to find new users and subject them to urine, blood or other testing. If the opiate narcotic-using population were much more widely dispersed, this would become extremely difficult.

THE TREATMENT OF OPIATE NARCOTIC USERS

I am in substantial agreement with the majority opinion on the matter of the treatment of the opiate narcotic user. While I share their view that in general the treatment of the user and the addict is a proper matter of provincial responsibility, I believe there are four roles that the Federal Government should play.

First, the use of opiate narcotics in treatment should be subject to continuing federal regulations. There are obvious advantages of uniformity. But my principal concern is to assure rigorous control over the use of these drugs. While the recent performance of the Federal Government is disappointing in the level of control that has been imposed on the prescribing of methadone, I believe that there is a greater probability of adequate controls on these drugs being maintained by the Federal Government than by ten separate jurisdictions. The evidence is clear that the improper prescribing of these drugs by only a very few physicians can quickly produce an epidemic. Such was the case in the United Kingdom where fewer than one-half dozen physicians, who were either fools or knaves, contributed significantly to the increased use of heroin and amphetamines. The effects of a lessening of proper controls in any one province could not likely be contained within its borders and could have serious material consequences. For example, much of the recent opiate narcotic problem in Windsor occurred as a result of improper methadone prescribing and dispensing in Detroit. The national border with its checks on movement was not an effective barrier. Provincial borders would present no barrier at all.

Second, the Federal Government should be prepared to establish, at the request of a provincial government, a full range of treatment facilities for opiate narcotic users.

Third, in the absence of adequate provincial treatment facilities for the care of users on parole, such facilities should be provided by the Federal Government. Presumably this is constitutionally possible insofar as they would be, in the context of my recommendations, under a sentence the length of which would place them under the control of the Federal Government.

Fourth, the Federal Government should organize training programs to be made available for provincially employed personnel concerned with the care and treatment of opiate narcotic users.

The Government and the various colleges of physicians and surgeons appear to have failed in adequately policing the prescription of opiate narcotics by physicians. They tend perhaps to be somewhat more effective in curbing malpractice by knaves than by fools or by physicians who are uninformed about the opiate narcotic problem. I recommend strongly that a greater vigilance be maintained over the prescribing of these drugs and that much more rigorous steps be taken to prevent unwise prescribing. Canadian, British and American experience amply demonstrates that three or four physicians can, through their prescribing practices, produce an epidemic of opiate narcotic or amphetamine use. There is little reason to feel confidence that existing mechanisms to control and regulate medical practice are adequate.

ADDITIONAL RECOMMENDATIONS CONCERNING THE OPIATE NARCOTICS

THEBAINE

The Bentley Compounds, derivatives of thebaine, an opium alkaloid, have not as yet become significant among the opiate narcotics used non-medically. However, because their potency is as much as 1,000 times that of morphine or heroin, they could become a serious problem. Consequently, I recommend that the Government of Canada treat the potent thebaine derivatives as heroin is now treated and urge other governments to follow suit.

COCAINE

In the course of inquiry we have heard many criticisms of existing law for its want of descriptive accuracy. In particular, the inclusion of cannabis in the Narcotic Control Act has been criticized, for clearly this drug is not a narcotic. This Act at present also deals with cocaine, which is no more a narcotic than cannabis. In fact the drug is much closer, in its effects, to the amphetamines than to the opiate narcotics.

At the present time cocaine is not in widespread use in Canada, although much more commonly used and far more readily available than was the case a few years ago. Curiosity about and interest in the drug have very markedly increased, and with them demand. Availability has also increased, and there is no reason to believe that it can be effectively curbed.

Unfortunately cocaine has become a status drug—the drug of the elite among the non-opiate-addicted, serious illicit drug users. Its use will almost certainly increase steadily.

I recommended that it be removed from the control of the Narcotic Control Act simply for reasons of accuracy, and that this be done before use has spread further.

In many ways it would be logical and consistent to classify it with the amphetamines. However, it would certainly not be wise to remove the possessional offence. Consequently, I suggest that cocaine be placed in a separate and distinct classification schedule under the Food and Drugs Act with penalties identical to those at present available under the Narcotic Control Act. If the use of this drug begins to reach alarming proportions, then consideration should be given to making use an offence enforceable by body fluid analysis.

• It is clear that thin-layer chromotography (TLC) as presently generally used in Canada is not sufficiently accurate to provide grounds, by itself, for conviction because of the risk of a false positive result. However, this method remains the best technique for widespread use. I would recommend that until better methods are available it should ordinarily be used, but when an opiate narcotic is detected by this method further tests should be applied and a positive result on two tests should be required for conviction. Consequently, enough fluid should always be taken to allow two analyses to be performed.

There is good reason to believe that within a short time the radioimmunoassay, FRAT and related methods will be able to meet all reasonable demands for accuracy, discrimination, economy and speed. When this is the case a positive result by one of these methods alone should be taken as adequate grounds for conviction.

The extremely sensitive immunoassay methods have other advantages as well. Using such techniques, it may be possible to detect the presence of opiate narcotics in the system for several days after use. Urine, blood or, possibly, saliva and sweat samples may be employed. At the present these techniques do not efficiently distinguish codeine from morphine, but it is expected that this difficulty will be overcome shortly.

Since heroin is converted to morphine and other metabolites in the body, it is generally difficult to efficiently discriminate between the use of these two drugs. However, I find that this is no problem since I would regard the illicit use of morphine as being as serious as the illicit use of heroin, methadone or the other narcotics excepting the low-dose use of codeine.

* A one- to three-year sentence with immediate parole is specified in this recommendation to ensure continuous supervision for a lengthy period of time. I have no objection in principle to providing this supervision by means of suspended sentence and probation but under existing law suspension of sentence and probation can be applied only when an offence carries no minimum sentence. While I am concerned with the lightness of sentences that have recently been imposed on many of those found guilty of opiate narcotic possession, I recognize real advantages in allowing the courts some measure of flexibility in dealing with these cases. However, available evidence strongly suggests that drug users require lengthy periods of close supervision if their rehabilitation is to be achieved.

t Until methods of analysis are improved, body fluid samples should be required daily or at least every second day. Hopefully methods will soon be available to accurately find opiate narcotics in the system several days after use. When this is the case, longer intervals between samples could be safely allowed.

# The determination of dependency must be based on clinical evidence. The decision as to whether dependency exists should rest with the court and should be based on evidence from physicians with special competence in the matter and others appropriately qualified.

§ All available evidence suggests that a lengthy period of supervision is imperative if there is to be any real hope of success in dealing with those dependent on the opiate narcotics (see Appendix K). The relatively low levels of success that have been achieved with addicts on probation and parole in Canada (see Appendices 7 and K) point to the need for lengthy periods of close control and supervision.

* Until methods of analysis are improved, body fluid samples should be required daily or at least every second day. Hopefully methods will soon be available to accurately find opiate narcotics in the system several days after use. When this is the case, longer intervals between samples could be safely allowed.