| - |

Drug Abuse

Note of Dissent by Raja Soshi Sikhareswar Roy from opinions expressed in the Report

It will be well, I believe, to mention here, before stating the principal points of difference with my colleagues, that I have thought it advisable to keep outside the sphere of my consideration the revenue question connected with the excise administration of the hemp drugs. The reasons for adopting this course are :—

(1) In the instructions to the Commission contained in Government of India Resolution No. 2792-Ex., dated 3rd July 1893, there is no mention of the revenue question.

(2) Looking to the past history of the use of intoxicating drugs in this country during the period of Hindu and Muhammadan rule, and also to the distinct principle laid down by the British Government while taking in hand the control of the use of these drugs, I have been led to think that I would not be justified in taking the question of revenue into my consideration while dealing with the advisability or otherwise of prohibiting the use of the drug.

A short sketch of the past history of the administrative control of intoxicating drugs in India will not be uninteresting if given here.

Manusmriti, or the Institute of Manu, is considered as the highest authority on the Hindu law. In Chapter VII of Manu are enumerated the different sources from which in ancient time the sovereigns of the country used to collect revenue from their subjects. No taxes on intoxicants are mentioned therein.

Neither in yagnabalka, Brihaspati, Atri Parasara, or in any other standard work of Smriti is there to be found any thing which could show that the custom of imposing taxes on intoxicating articles existed. There is ample proof to show that in ancient India the use of intoxicants was not uncommon. Even in the Vedas not only the mention of the word sura (spirituous liquor) is found every now and then, but it also appears that the use of soma drink—that is, leaves of a kind of plant in the form of an infusion—was very common among the ancient Rishis. Whether the soma plant bears any resemblance or relationship to the hemp, as has been said by some witnesses (witness No. 69, Central Provinces, and others), or as stated in para. 15 of the report on the cultivation of ganja by Babu Hem Chunder Kerr, is a point on which there is great difference of opinion ; but this much is certain that in ancient India there were other intoxicating drinks than wine.(1) But it was the manufacture and sale of spirituous liquors alone that were prohibited by law. "*(2) The distillers and sellers of spirituous liquors should be banished from the realm of a king, as they are secret thieves and harass the subjects by their ill deeds. "—Chapter IX, Stokes 225 and 226 Manusmriti.

During the Muhammadan rule in India attempts were made from time to time to impose duty on certain intoxicating beverages, but it is not clear how far the use of intoxicating articles was actually brought under direct control of the governing power. It is not unknown to those who have studied Muhammadan history carefully that the sources of revenue as well as the collection of revenue during the Muhammadan rule reached their highest point under the sovereignty of Aurangzeb. In Catrou's Histoire generale de l' empire du Mogol, a list is given of the different sources of revenue from different provinces which were under the sovereignty of Aurangzeb. Nothing is to be found in this work which shows that there was any duty imposed on the use of intoxicating articles. On the other hand, an interesting account of his aversion to the very idea of imposing taxes on intoxicating drugs will be found in a Persian book which contains a collection of his letters written by him to his friends and relations. Aurangzeb's grandson proposed to impose a tax on palm juice, a very mild intoxicating beverage which was then in great favour among certain classes of Hindus in Bengal. .Aurangzeb's answer in reply to his grandson's proposal was as follows :—

" Though the taxation of the palm may lead to the collection of revenue, yet it is impossible for me to sanction it. I cannot understand what dishonest mufti declared it legal to do so. You must know that such ill advisers are enemies of this and the next world. You should thank Almighty who has put you in possession of three provinces which are so full in wealth, and which fill our coffers with so much revenue, and in which everything is so abundant and cheap. You should know as well that the good-will of the subjects is the only wealth for this world and the next." (Letter No. 9o.)

Later on, during the closing period of Muhammadan rule, some sort of taxes were imposed on the trade of spirituous liquors in some parts of the country, and it appears that these were collected under the head of sayer revenue by the zamindars when the country came under the possession of the East India Company from the hands of the Muhammadan rulers.

In 1789 a cry was raised in some quarters against the conduct of the Bengal zamindars, and it was said that, owing to the want of proper control on the part of the zamindars, the vice of drunkenness was spreading very fast among the lower classes of the people, and it was suggested that the proper remedy of this evil would be for the Government to bring the collection of the duty on spirituous liquor under its direct control and management. Accordingly, on the 19th April 1790, by a general notification the Government decided upon the resumption of the sayer on spirituous liquor. This was followed by the Abkari Regulation of the 14th January 1791, the main provisions of which were as follows : "That a tax should be levied on every license granted both to distillers and vendors of spirituous liquors ; that the rates of tax on the licenses should be regulated by the local situation of the stills and shops, the quantity of consumption, and selling price ; * * * that all private unlicensed stills should be prohibited under penalties."

On the 16th February 1798 the Board of Revenue suggested that a duty be levied on the sale and consumption of (I) madak, (2) ganja, (3) subzi, (4) bhang, (5) majum, (6) banker, and (7) charas. On the 22nd March 1798, the President (the Governor-General in Council) replied as follows: " Some of the articles enumerated in your letter, we have reason to believe, ;-.re of so noxious a quality, and produce a species of intoxication so extremely violent, that they cannot be used without imminent danger to the individual as well as to the public who may be exposed to the effects of the temporary insanity frequently excited by the use of these drugs. We are of opinion that the vend of any drugs of this description should be altogether prohibited, and we desire therefore that, after having made an inquiry with a view to ascertain more particularly the nature and effect of them, you will prepare and submit to us a regulation for this purpose, as well as for establishing such duties as may appear to you proper on the sale of such other drugs as may be used without the same pernicious effects."

The Board of Revenue made inquiries under the above order, and arrived at the conclusion that tobacco, opium, ganja, bhang or subzi, banker, and toddy are not for the most part represented as producing any very violent and dangerous effects of intoxication except when • taken to excess, and that they appear to be useful either as medicine or otherwise. For these reasons the Board of Revenue thought it advisable to recommend that the sale of any of these articles should not be altogether prohibited, but that in order to restrict their use a tax should be imposed on them.

Accordingly unlicensed sale of ganja and other intoxicating drugs was prohibited, and a daily rate of duty on the sale of ganja and other intoxicating drugs according to their strength and quantities was imposed on them by Regulation VI of 1800. In 1853 the system of daily tax on intoxicating drugs was abolished, and in its place a duty at Re. 1 per ser on ganja and charas was imposed. In 186o a fixed fee of Rs. 4 per maund was prescribed for each ganja license in addition to the above fixed duty. In 1876 the present system of annually selling by auction the retail licenses was introduced. On the 29th April 1875 the Government of India addressed a letter to the Government of Bengal, in which it observed that " nothing should be done to place temptation in the way of the people that can possibly be avoided." It was also stated : " His Honour the Lieutenant-Governor may rest assured of receiving the support of the Government of India in any measure that he may adopt for limiting the consumption of ganja; and indeed if the use of the drug could be altogether suppressed without the fear of leading to its contraband use, such a course would be justified by its deleterious effects."

In 1871 Sir Richard Temple, while he was Financial Member of the Government of India, drew the attention of the Government to a note, dated 15th July 187o, by Mr. Chapman, the Financial Secretary, in which he made an observation to the effect " that every lunatic asylum report was full of instances of insanity and crime due to the use of ganja." The result was that Local Governments were directed by the Government of India to make a thorough investigation in regard to the effects of the use or abuse of the several preparations of hemp. Mr. Hume, then Secretary to the Government of India, in his letter No. 339, dated loth October 1871, wrote to all Local Governments and Administrations as follows : " It has frequently been alleged that the abuse of ganja produces insanity and other dangerous effects. The information available in support of these allegations is avowedly imperfect, and it does not appear that the attention of the officers in charge of lunatic asylums has been systematically directed to ascertain the extent to which the use of the drug produces insanity. But as it is desirable to make a complete and careful inquiry into the matter, the Governor-General in Council requests that, with the permission of His Honour the Lieutenant-Governor, you will be so good as to cause such investigations as are feasible to be carried out in regard to the effects of the use or abuse of the several preparations of hemp. The inquiry should not be simply medical, but should include the alleged influence of ganja and bhang in exciting to violent crime."

The result of this investigation was embodied in a Resolution by the Government of India, dated 17th December 1873, and it was decided by the Government that the cultivation and consumption of ganja should be absolutely prohibited in British Burma, and that restrictions should beimposed on the cultivation, possession, and sale of ganja in the Central Provinces, the Chief Commissioner of which suggested the adoption of such a course on the ground that " the consumption of drugs has of late years materially increased in the Central Provinces, and fears have been expressed by district officers that since the introduction of the public central distillery system and the consequent rise in the price of spirits, many people who formerly drank spirits have taken to drugs as a substitute." The Local Governments of other provinces and presidencies were not in favour of altering existing arrangements, so the Government of India did not press them for the adoption of any restrictive measures of a stringent character, although in the concluding portion of the Resolution the wish of the Government to discourage the use of ganja was expressed in a general way in the following words : " His Excellency in Council, however, trusts that the various Local Governments and Administrations will endeavour, wherever it may be possible, to discourage the consumption of ganja and bhang by placing restrictions on their cultivation, preparation, and retail, and imposing on their use as high a rate of duty as can be levied without inducing illicit practices."

In July 1891, Mr. Mark Stewart, M.P., in the House of Commons, drew the attention of the Secretary of State for India to a statement which appeared in some Indian paper regarding the injurious effect of ganja, and requested him to call the attention of the Government of India to the desirability of extending the same prohibition as adopted for Burma to the other provinces of British India. The Right Honourable the Secretary of State for India accordingly, in his despatch dated 6th August 1892, requested from the Government of India an expression of its views on the effects of this drug, and asked if the Government of India would propose to take any further steps for restricting the consumption. The Government of India in reply wrote a letter to the Secretary of State on the 9th August 1892, in paragraph 3 of which it admitted the injurious effects of the drug in the following words: " We are inclined to believe that ganja is the most noxious of all intoxicants now commonly used in India. But, even if the absolute prohibition of the use of the drug could be enforced, the result might be to induce the use of still more noxious drugs. India abounds with plants, growing wild, from which drugs can be procured which are more deleterious in their effects than ganja But although we consider it impracticable to enforce the absolute prohibition of the use of ganja, we fully recognise it as our duty to restrict its consumption as far as practicable, and we have distinctly laid down the policy to be pursued in respect of this drug in our Resolution of the 17th December 1873 already quoted."

It will be seen from the above sketch that the use of intoxicating drugs was not uncommon in ancient India, but the restrictive measures adopted in those times differed from those now existing, inasmuch as the attempt then made to restrict the use of spirituous liquors was not by imposition of taxes as is done now, but by disallowing the sale and manufacture under some severe penalty. In the latter portion of the Muhammadan rule, however, some sort of duty was imposed on vend of spirituous liquors, but it did very little to check their spread. The hiStory of the control of the use of the intoxicating drugs during the last century under the British rule will show most clearly that although the Government is trying its best to check their spread by adopting various restrictive measures from time to time, yet the result is not always satisfactory to the Government itself. It will also show that the Government is fully aware of the injurious effects caused by the use of these drugs, and that it is ready to prohibit their sale, manufacture, and importation if only it is fully convinced of the practicability of the measure. With this view, and to estimate aright the exact measure of the injury done to the people at large by the use of these deleterious drugs, Government caused inquiries to be instituted from time to time. But, failing to come to any satisfactory conclusion, the Government has been pleased to appoint the present Commission to institute further inquiries concerning the subject.

To obtain exact knowledge of the subject of their inquiry, the Commission directed their attention to the following, five principal methods for eliciting information :—

(1) By examining witnesses from various provinces.

(2) By examination of cases attributed to hemp drugs in lunatic asylums.

(3) By causing scientific investigation to be made in regard to physiological action of hemp drugs, etc.

(4) By reading official records and current literature bearing on the subject.

(5) By personal observation of the habits and condition of the consumers of these drugs in various parts of India.

With regard to (t), all the members of the Commission as a body had -opportunity of judging for themselves the value of the evidence taken before them. The inquiry (2) was conducted by a Sub-Committee consisting of two members of the Commission, while (3) scientific investigation was conducted not by any member of the Commission nor in their presence, but by a medical man at the request of the Commission.

As regards evidence of witnesses, it will be well to mention here the difficulties and disadvantages which the members have had to work under for the following reasons :—

(1) The subject of inquiry was not of such a nature as to induce men of educated classes or well-to-do people of native society to take any special interest in it, so I think it can be safely said that the bulk of • our witnesses had very little practical knowledge or personal observation of their own regarding the subject-matter of our inquiry, and this fact is borne out in many instances by their own statements.

(2) The time available for answering the long series of questions framed by the Commission was in the majority of cases not sufficient for the witnesses to make a thorough study of the subject in all its bearings.

(3) For the reasons abovementioned, most of the witnesses have had to depend mainly on hearsay statements of other people—a fact which in many instances was admitted in their answers.

(4) The Commission tried to get information from the people who have special knowledge of the subject, but those people, having no knowledge of English, answered the questions from a translation sent to them which was not always very accurate, as will be seen from paragraph Io5 of the report. The evidence thus obtained also got distorted in some cases by re-translation. This fact was elicited in some cases when they were orally examined, and :of course the mistakes of the translation were at once corrected. But for those who were not orally examined it is difficult to say how far their papers are still open to correction, as they have not had any opportunity of reading their answers in print.

(5) The three drugs—ganja, charas, and bhang—having been grouped together in one and the same question, the witnesses in many cases made a confusion in their answers,—a fact which was brought to light at the time when some of them were orally examined.

(6) The evidence in all cases was not noted down in the exact words of the witnesses while orally examined, the substance of their statements having been recorded in the writer's own language. The fact also that the portion of the answers was not put side by side with the corresponding questions put to the witnesses goes to diminish the value of such evidence to some extent.

(7) In some cases the witnesses were prejudiced in answering the Commission's questions on account of their holding a wrong notion of the object of the Commission's present inquiry. This fact came to my knowledge from casual remarks of some of the witnesses as well as of other people in different places where opportunities were placed before them to express their free opinion. A remark which was made by one of the high officials of the Indore State at one of the sittings of the Commission there also shows that in many places people misunderstood the motive of the present inquiry.

(8) The other disadvantages under which the members had to work need not be mentioned here in detail, as they may be seen from the proceedings book of the Commission.

Although there are thus some disadvantages and difficulties above indicated, yet the evidence of so large a number of witnesses examined by the Commission cannot fail to throw some light which will assist in coming to a general conclusion.

It would not be difficult to quote from the evidence before us any amount of opinion either in favour of ganja to show that its use is not injurious, or against the use of ganja to prove that it is highly deleterious and most harmful; so, without attempting to quote individual opinions, I will be content with showing in a general way their views on the subject matter of our inquiry.

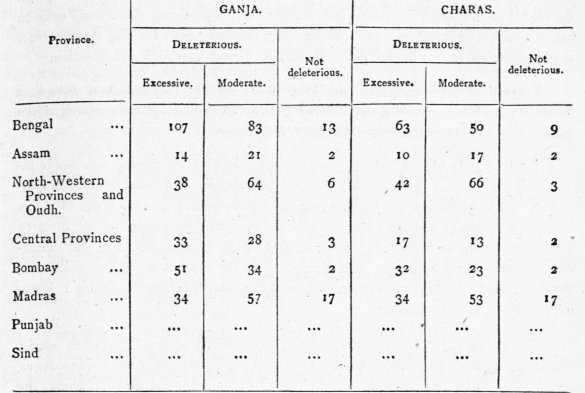

The following is an analysis of the opinion of witnesses on the question of injurious effects of the hemp drugs :—

A careful examination of the statements of witnesses will show that an overwhelming majority of the superior medical officers are of opinion that the hemp drugs are very deleterious in their effects (some even go so far as to say that they are so even when used moderately), and that their excessive use brings on insanity and other diseases. The large number of executive officers, while generally agreeing in the view that the use of these drugs is not so injurious in their effect as above described, have proposed at the same time that the duty at present levied on them should be raised. The consensus of opinion among most of the witnesses belonging to the orthodox Hindoo class is that the use of bhang is connected with the social and religious customs of the people, but it would be well to point out here that a very few of them consider such customs as absolutely essential. The opinion of some of the Muhammadan and European witnesses is that the use is essential. The enlightened portion of the native community who were invited to give evidence generally share in the view that these drugs are injurious, and that their use may be prohibited. The reason for this diversity of opinion is not far to seek. On the one hand, the patriots and philanthropists in their excessive zeal for the welfare of the people are generally apt to magnify the existing evils which corrode society, however small they may appear to the naked eye ; while, on the other hand, another class, with a view to serve the interests of the State, generally make the evils appear very much smaller, like things seen through the wrong end of the binocular glass, forgetting that the interest of the Government could be best served by serving the interest of the people.

About the examination of cases admitted to the lunatic asylums where the cause of insanity was attributed to hemp drugs, it may be said that the Commission's inquiry extended over a period of one year, namely, 1892, and the conclusion arrived at, however correct it may be for that year, cannot perhaps be accepted as general. What leads me to form this opinion is that the nature of the evidence on which the Sub-Committee based its decision is in some instances of a very contradictory and unreliable nature. In this connection my suggestion would be that the statistics of such cases for the next succeeding three years may be taken, and the local officers be impressed with the necessity of taking down correct notes of the nature of insanity, its causes, &c., after thorough examination.

I think I need hardly say anything more on the physiological action of hemp drugs than by quoting the following from Dr. Cunningham's report, which proves that the investigation is not yet complete :-

" The results of this were as follows, in so far as mere casual naked-eye inspection goes ; for I have already pointed out the detailed histological examination of the condition of the various organs and tissues is a matter not of a few hours, but of many weeks' work ; so that it has been impossible for me to carry it out and at the same time to meet the wish of the Commission for the immediate submission of a report. Specimens of all the more important organs have, however, been carefully preserved, and will form the subjects of detailed histological examination hereafter."

The principal recommendation of the Commission is that, in order to restrict the use of these drugs, a high rate of duty should be imposed on them. Considering the peculiar condition of this country and its population, I do not think the doctrine of restricting the use of intoxicants by introducing a gradual increased rate of duty on their trade could be accepted as a very sound one. The past history of the excise administration of the country will show clearly that such measures, although adopted from time to time, were not of much avail. To prove this it would be necessary either to point to facts and figures in official reports or to quote public opinions. If it is possible to find accurate figures of area under cultivation or actual quantities of production of the intoxicating drugs for a series of years, the actual increase or decrease of the use of the drugs could be inferred from an examination and comparison of those figures. The following extract from a letter of the Government of Bengal to the Board of Revenue will show that the Government itself has very little confidence on the statistical tables prepared in the Excise Department :—

" The Lieutenant-Governor has had an opportunity of visiting Nowgong and of personally inspecting the Ganja Department at the place; and from inquiries made by him on the spot, it appears to him that the widest opportunities for fraud and smuggling exist, though no proof has ever been adduced of detected smuggling of ganja on an extensive scale. The cultivated area is never measured. The result therefore at the end is entirely speculative and uncertain."

The Acting Secretary to the Madras Board of Revenue in the Department of Separate Revenue in his letter No. 1839-Mis., dated 1st May 1894, says : " Accurate figures are nowhere available, as no accounts are maintained respecting the cultivation of the plant." Such is the case with every province. Nowhere accurate figures regarding the cultivation or production of ganja are available. However, if we are to depend on the reports of the Excise Department, it will be seen from an examination of these statistical tables that, notwithstanding a continuous raising of duties on ganja, its cultivation and trade are markedly on the increase. The rates of fixed duty have been raised. in Bengal from time to time. For the sake of convenience I will divide the twenty years from 1874 to 1893 into as many periods as the rates of duty on the drugs were increased and give an average of areas under cultivation, etc., for each period. In this manner their effect on the spread of cultivation and trade of the drug will be seen most clearly. In five years from 1872 to 1878 the rate of duty on " best "quality of ganja was Rs. 4, the area under cultivation 1,978 bighas, sale 7,800 maunds, import 83o maunds, and revenue Rs. 11,67,829. In the next four years from 1879 to 1882 the rate of duty on round ganja increased a little, the area under cultivation was 1,982 bighas, sale 5,657 maunds, import 879 maunds, and revenue Rs. 14,51,088. In the next five years from 1883 to 1887, rate of duty Rs. 5, area under cultivation 2,010 bighas, sale 5,861 maunds, import 1,416 maunds, and revenue Rs. 39,68,822. In the next three years ending 1890, rate of duty Rs. 7, area under cultivation 2,207 bighas, sale 6,354 maunds, import 1,713 maunds, and revenue Rs. 22,74,354. In the next three years from 1890 to 3893, rate of duty Rs. 8, area under cultivation 2,509 bighas, sale 5,741 maunds, import 1,571 maunds, and revenue Rs. 23,30,106. It will be seen from the last yeax's report that the area under cultivation was no less than 3,540 bighas in 1892-93. -

I think it would be well to see what the statements of the witnesses prove regarding the spread of the use of hemp drugs. No. 1 Bengal witness, Mr. D. R. Lyall, Member of the Board of Revenue, in charge of Excise in Bengal, says in reply to Question No. 25 : " The consumption of ganja varies little." Mr. E. Westmacott (Witness No. 2), late Commissioner of Excise in Bengal, says : " I doubt there being either increase or decrease. If smuggling were completely stopped, figures of consumption'would undoubtedly go up." Mr. William Colebrook Taylor (36), Special Deputy Collector, Orissa, says : " The use of ganja is said to be on the increase. Cannot give reasons except that the existence of so many ganja shops must have a tendency to attract consumers and increase the consumption." Mr. A. C. Tute, Collector of Dinajpur, witness No. 12, says : " The use of ganja is on the increase. The reason for increase in consumption here is that the people of this district show a liking to ganja in preference to drink." Witness No. 166, Ray Radhagobind Roy Sahib, Zamindar of the same district, says : " The use of ganja is on the increase." Witness No. 92, Mr. W. R. Rickets, Manager of Nilgiri State, Orissa, says : " I should say the use of bhang and ganja is decidedly on the increase." Witness No. 8o, Babu Hem Chunder Kerr, the Deputy Collector of Alipur, and the well-known author of the valuable report on ganja, says : " With increase of duty smuggling becomes more rife (vide my Report, page 153). The first improvement that I would suggest will be the reduction of the duty levied on ganja, which has been raised rather too high."

In the North-Western Provinces the increase in the use of hemp drugs is not less marked than in Bengal. Mr. Stoker, the Excise Commissioner of North. Western Provinces, in paragraph 42 of his memorandum says : " In the twenty years since 1873 the receipts have grown from Rs. 4,07,822 to Rs. 7,06,788, or over 73 per cent. In Oudh the increase has been over 193 per cent., and in the North-Western Provinces it has been 5o per cent." For this increase he has assigned three causes, one of which is " an increased use of hemp drugs."

In Punjab the Financial Commissioner's letter, dated 6th October 1891, contains the following : " So far as statistics are available, the revenue derived from the Punjab from the hemp drugs has remained practically stationary for several years. (3) The probabilities are all in favour of increased consumption."

A careful examination of Excise reports and statements of witnesses in other provinces will show that the use of hemp drugs is spreading in the same way everywhere, and, wherever it will be found otherwise, the cause may be easily traced to the spread of the use of spirituous liquors. The question of the spread of the use of hemp drugs is so much intermixed with that of opium and spirituous liquors that it is not at all convenient for anybody to deal with the one kind of intoxicating article alone, keeping the others outside the sphere of consideration. The principle of restricting and controlling the spread of intoxicating articles by imposing high rates of duty has been applied to all, but notwithstanding this the use of every kind of intoxicant is on the increase. Attempt has been made from time to time to explain away this increase of intemperance as well as the revenue derived from the use of intoxicating articles in India by officials of the highest position and experience by bringing forth the argument that it is the result of the improvement in the condition of the people. Sir J. Strachey in page 30 of his admirable work, " Finances and Public Works of India," says : " This increase-of 5o per cent. in the last twelve years is not to be attributed to the increase of intemperance, but to improvement in the condition of the people, and, still more, to better administration."

Sir Richard Temple in his " India in 188o " says : "The sight of this may give to some observers the impression that under British rule drinking prevails more than under Native rule. Wider observation will, however, prove that the Indians, if judged by the standard of advanced nations, are sober and temperate in the main, and that, despite any defects which may still lurk in the excise system, the British taxes do operate as some check upon insobriety."

Probably nowhere this line of reasoning was more clearly and effectively put before the public than in a Parliamentary Report on " Intemperance" prepared by a Select Committee of the House of Lords. It is stated in that paper: " This increase of expenditure cannot by itself be taken as a proof that drunkenness has increased in the same ratio. It is probable that a large portion represents the moderate consumption by the temperate. With increasing incomes the spending power of all classes has grown, and a higher scale of comfort has been gradually introduced. Just as the consumption of meat has increased, so has that of intoxicating liquors ; but in neither of these cases does the increased general consumption necessarily imply a proportionate excess on the part of individuals. 'Further, it has been shown that the use of tea, sugar, wine, and tobacco has increased far more rapidly than the use of spirits or beer."

Whatever may be the cause of the increase, in this country at least it is believed by many the use of the intoxicating drugs is spreading very fast. An experienced officer of the executive line in Bengal, Mr. Dutt, Deputy Magistrate, in page 276 of his book " India : Past and Present " says : " The vice of drunkenness has been most alarmingly increasing in the country since the introduction of British rule in it. Of course the raising of the excise duties would necessitate the raising of the import duties on foreign liquor, as otherwise the result would be to displace Native liquor for European ; and it is here that the shoe really pinches, for the Europeans in India, and possibly the higher classes of the Natives also, are apt to object strenuously to any check being placed on the admission of European liquors into the country."

These few lines will show how keenly some of the educated natives of the country feel for the spread of the use of spirituous liquors and other intoxicating drugs among the people, and how necessary it is to find out some effective means which might arrest their further progress. The simple course of raising the rate of duty from time to time to check their spread has not proved of much avail up to this time. On the other hand, I believe the rates of duty on some of the intoxicating articles have already reached their highest point, and, instead of checking the spread of their use, do harm to society by fostering smuggling and crimes. In my humble opinion, adoption of an opposite course in the shape of gradual reduction of duties on some of the intoxicating articles, with a judicious arrangement for supplying the consumers of the drugs with the least injurious.kind of intoxicants, may in a great extent help to fulfil the wish which the Government has at heart.

Sometimes judicious reduction of the duty on articles of consumption, such as drinks or beverages, has proved far more beneficial than the adoption of restrictive measure in the shape of imposing increased duty. To prove this, instances abound in the history of England as well as of other European countries. As an instance, I may mention here the case of tea. In the last century, when the use of tea spread in an astonishing way all over England, and when the traders in tea used to mix with it " great quantities of sloe leaves, liquorice leaves, leaves of other trees, shrubs, or plants, clay, logwood, and other ingredients," which were detrimenta.1 to the health of the people, Government with the help of legislation attempted several times to repress the sophisticating of tea, as these operations of the false tea-makers were termed. But such measures always proved quite ineffectual. A very stringent Act was passed in 1777 to repress this practice, but it also did very little good. At last, in 1784, a wise measure was adopted by Pitt, and a considerable reduction in the duty on the tea cheapened its price and repressed smuggling.

It would not be improper to see here how far the quite different line of method which the Government adopted to arrest the progress of hemp drugs in Burma has proved successful.

The following extracts will show that the prohibition of the sale and manufacture of ganja in Burma has proved of some benefit to the country :-

Mr. Bayne, Secretary to the Chief Commissioner, in his letter dated 2nd November 1893, says : " No one in Burma desires any change in the Excise law as far as intoxicating drugs are concerned." The Commissioner of theTenasserim Division, in his letter dated 3oth January 1894, addressed to the Financial Commissioner, says : " The effect of the prohibitory system has undoubtedly been to render it somewhat difficult and dangerous for any one to possess the drug, and this must have very largely tended to keep it out of the hands of Burmans. In my opinion, if this system had not been adopted, the result would have been disastrous. Burmans would very certainly have taken to use ganja, for which they have no desire, and, from their national character, those who took to it would have used it to excess, as is the case with opium, which taken in moderate doses does no harm. Were the consumption and even possession of ganja not prohibited, the effects would be terrible." In his memorandum dated 1st June 1893, Mr. Culloden, Superintendent of Preventive Service, says : " Ganja has always been considered a prohibited drug in Burma. The prohibition of its importation has so far been successful that the drug has been kept out of the local market to a considerable extent ; this is proved by the fact that, whenever traced to any one possessing it, only a very small quantity of the drug has been found on them." The Deputy Commissioner, Akyab, in paragraph 3 of his letter dated 1st December 1893, says : " The system of prohibition has on the whole been successful." The Deputy Commissioner of Toungoo, in his letter dated 12th January 1894, says : " In my opinion the system of prohibiting ganja in Burma has been to a very large extent, though not entirely, successful." The Commissioner of the Southern Division, in his letter dated 16th January 1894, says : " As far as my experience goes, the system of prohibition of ganja has worked well. This is based on my experience in different places." Major Eyre (Witness No. 12) in his evidence says : " The total prohibition now in force is absolutely necessary. Were the use of the drug to be sanctioned, the spread of the habit would be great and the results lamentable." Mr. Courneuve (Witness No. 14) says : "The absolute prohibition of the production and consumption of ganja has had the best results, and cannot be improved upon."

Consideration of all these leads me to come to a conclusion which is not quite in agreement with that of my colleagues. I believe that the injurious effects of the hemp drugs are greater and their use more harmful than one would naturally suppose to be the case after reading the concluding portion of Chapter XIII of our Report, although I think I should say that the facts elicited by our inquiry do not go to support the extreme opinion held by some well-intentioned people that these drugs in all their forms and in every case are highly pernicious in their effects. We have seen in almost all parts of India people connected with temples and maths, who are quite healthy, strong, and stout, who excessively indulge in bhang. Instances were not rare in which habitual ganja smokers were seen to be quite healthy and strong. It is among the very poor and the mendicant classes that shocking instances of human wrecks caused by over-indulgence in hemp drugs can be found. The general opinion that I have been able to form is that ganja and charas are no doubt injurious in their action on the constitution of certain people, especially those who are weak and underfed, even when they are taken in comparatively moderate doses, and only for a short time. When they are consumed in excess and continuously for a long time, their effects are undoubtedly most ruinous. It should be remembered that it is the men of the poorest class generally, who cannot afford to pay for the luxury of spirituous drinks, who take to the use of ganja. It is also a fact that men who are naturally weak, and who suffer from some sort of bodily or mental indisposition or discomfort, to obtain temporary relief generally indulge in ganja, at first in medicinal doses, and then gradually turn to be excessive consumers of the drug. This accounts for the fact why so large a number of the consumers of the drugs are often found to be in a most deplorable condition. On the whole, therefore, I am inclined to believe that the prohibition of the use of ganja and charas would be a source of benefit to the people.

The following chief difficulties are generally alleged in the way of total prohibition :—

(1) Probability of the consumers taking to the use of more deleterious drugs.

(2) Wild growth of hemp plant.

(3) Religious consideration.

It is said that the prohibition of the use of ganja and charas might lead the consumers to take to more deleterious and worse substitutes, such as dhatura, arsenic, etc. It should be noted that out of 1,193 witnesses, probably not more than twenty of the non-officials have shared this view. No doubt some of the consumers of ganja and charas will take to the use of spirituous liquor and some may go to opium, but at the same time it is reasonable to believe that a large number of them will not go to either. The reason is that fakirs and bairagis, who are the largest consumers of the hemp drugs, cannot on religious grounds resort to spirituous drink. It is stated by many witnesses that opium is distasteful to the consumers of ganja. Even supposing some of them go to toddy, pachai, weak country spirits, or even moderate doses of opium, the proofs are wanting to show that these forms of intoxicants are worse in their effects than ganja and charas smoking. Besides, if one of the forms of the hemp drugs—bhang,—which is considered least injurious, is left untouched by the prohibitory measure of the Government, consumers of ganja or charas will get in it a substitute, though weak in intoxicating strength. So I do not think there is much ground for the •fear entertained by some that the stronger poisons, such as dhatura, arsenic, etc., might be substituted for any of these drugs.

It will be seen from the map showing the spontaneous growth of the hemp plant appended to the Report that such growth is only confined to the Himalayas, and portions of the plains adjoining it. In Southern India occasional growth of the plants may be found here and there, but not even to the same extent as they can be, found in Burma. If notwithstanding this the system of prohibition was thought feasible in Burma, there seems hardly to be any reason for not extending the same-at least to Southern India.

In Chapter II (on Natural History of the Hemp Plant) of the Report it is stated :

"The evidence of botanists, therefore, may be taken to exclude India from the area of indigenous growth, and it will be seen that the direct enquiries of the Commission tend to confirm this view."

In the memorandum of the Bengal Excise Commissioner, paragraph 6, it is stated : " The wild hemp plant is found in nearly every district, and it grows abundantly in several places. No ganja or charas is made from the wild plant, as the narcotic element which is essential to the production of either drug is entirely absent or very imperfectly developed in the uncultivated plant." The Excise Commissioner of the Central Provinces, in paragraph 57 of his memorandum, says : " It is believed that the hemp plant does not grow wild in any part of those provinces."

The Excise Commissioner of Assam in his evidence in reply to our question No. 7 says : " I think there is no such thing as wild ganja. It does not grow of itself like other weeds. " Statements of this nature abound in excise memoranda and other records.

Further, in paragraph 665 of Chapter XVI of the Report it is stated : " That the ganja derived from such spontaneous growth, untended and unimproved, is so inferior as to obviate all likelihood of its competing with the cultivated ganja."

The fact, therefore, that the plants are found only in certain parts of the country and not all over it shows that the objection on this score is not very tenable, and that there is hardly any likelihood of the flowering tops produced by the uncared for hemp plants being ever substituted for cultivated ganja. As regards charas, it being imported from foreign country, the spontaneous growth of hemp plant does not affect the question of its prohibition.

In Chapter IX of the Report it has been proved that charas has no connection whatever with any religious observances of any sect of people in India. It would also appear that the use of ganja in this connection is not so widespread as that of bhang. A careful examination of the statements of witnesses will show that the use is confined to a very small circle of people, and even that use cannot be considered as essential, as it is not sanctioned by any religious authority.

A very few witnesses, and these mainly from Bengal, mention that the smoking of ganja is connected with religious customs of the people. The majority of these refer to a mode of worship called Trinath Mela, which is in vogue in the Eastern part of Bengal and in some portion of Assam adjoining East Bengal. It would not be out of place here to state in brief the origin of this form of worship, and how far the use of ganja is really connected with it, and the connection of Trinath itself with the Hindu Trinity.

Major Moore in his " Hindu Pantheon," says : " In mythology Brahma is the creator, Vishnu the preserver, and Siva the destroyer ; in metaphysics the first is matter, the second spirit, and the third time ; and in natural philosophy, earth, water, and fire respectively." Perhaps it was with the object of bringing about a sort of reconciliation as it were among the different sects of Hindus who worship their god in these three different principles that one Babu Annada Chandra, a Varendro Brahmin of Dacca District, probably following the examples of Ram Sing of the Punjab or Ghasi Das of the. Central Provinces, first started this new mode of worship in 1869 somewhere near his native village, this deity being termed " Trinath," or three in one. To popularize this mode of worship among the rural .population, he himself composed a few stanzas of song in colloquial Bengali, which are sung instead of the usual citation of Sanskrit Muntras, while the worshippers of Trinath join together in performing the Puja. In these songs there is to be found only the mention of the word siddhi, i.e., bhang and not ganja. The originator of this mode of worship, himself being addicted to the use of ganja, it was natural that his followers would follow his example and offer ganja to their god while worshipping him. That the use of ganja is not essential in this Mode of worship can be ascertained from the fact that the ladies of the family are allowed to join with the male members in the worship, and it is known to everybody that women in Bengal as well as in other parts of the country, with the exception of those who publicly lead a disreputable life, never indulge in ganja or charas smoking.

Bengal witness No. 63, Babu Abhilas Chandra Mukharji, in his detailed note on Trinatha Puja, writes : " Ganja can be consumed by all in the name of a god, and the practice cannot be looked down upon, because it is done under certain forms and religious ceremonies." He concludes his paper saying : " The worship is on the decline. It is almost dying out among the educated bhadrolokes ; but among the masses it still exists." So from these it appears that ganja or bhang is offered to Trinath, but its consumption is not essentially a part of the religious ceremonies to be observed in connection with this mode of worship.

It is to be greatly regretted that the class of men, such as pandits, mohunts, gossains, gurus, and priests, on whose statements reliance could be placed in matters connected with Hindu religion, and whose opinions could be accepted as authoritative, are almost totally wanting in the lists of gentlemen who have been asked to answer our questions. Out of 264 witnesses in the North-Western Provinces, only one mohunt is to be found, and that witness (No. 242, North-Western Provinces, Mohunt Kishoram Rai) says in answer to our inquiry if the use of ganja is considered essential in religious observances of Hindus : " There is no religious injunction to take the drugs. The rule has been invented by the consumers. The drugs are taken in connection with the worship of Mahadeo with the idea of becoming naked like the god, and regardless of earthly things."

Witness No. 239, Lala Balmukand, Governor, Arya Samaj, says : " No customs, social or religious, sanction the use of ganja and charas. Bhang is regarded as the favourite drink of Siva (deity), and is used on the occasions of the festivals over which he presides, e.g., Shivratri, the anniversary of Siva's marriage ; but the use of the drugs is not regarded as essential. It is generally temperate. It is not likely to lead to the formation of the habit, nor is otherwise injurious."

Witness No. 240, Priest Kashi Prosad Panda, of Mirzapur, says : " There is no religious view to support the use of these :"

In the Madras Presidency, out of 193 there are only 3 witnesses who either belong to the priest class or are connected with the management of Hindu temples. Witness No. 191, Samdasu Bavaji, priest of the Mutt of Sri Jagannadha Swamy, says : " The use of ganja is not considered as an essential to social or religious customs as some say." No. 192, Baldev Das, priest of Hanuman Mutt, says : " Some think it necessary for religious thoughts. Those who consume it for religious purposes use it moderately." Then, in answer to our question No. 34, he says : " It would be well to stop it, though it would be somewhat difficult to the habitual consumers." Witness No. 127, Raja of Ramnad, the head of Rameswar temple, one of the four great temples of India, says : " I am not aware of any custom, social or religious, with which the consumption of the drug is associated."

In the Bombay Presidency the only witness, Sewak Lall Sarsondas (No. 109), who Is connected with a religious institution called "Arya Samaj," says : "The Arya Samaj fully sympathises with the objects of the Commission referred to, as the principles and tenets of the Samaj enjoin on its members total abstinence from all kinds of intoxicating drugs."

In the Punjab two religious associations only have favoured us with their opinions. The " Sanatan Dharma Sava, " of orthodox Hindus, says : " The beverage of bhang is sacred to the Siva, and in certain forms of worship is considered indispensable by certain classes of the votaries of Siva." " Arya Samaj," of Dera Ismail Khan, sent us copies of their resolutions, which are as follows : " That, in the opinion of this Samaj, the system in force in the Punjab regarding the preparation and sale of ganja and other hemp drugs is most defective, inasmuch as it affords facility for their consumption which deteriorates mental capacities and the health of the consumers ;" (2) "that this Samaj is of opinion that the sale of the hemp drugs should be restricted to the medical profession for medical purposes, and the preparation be so restricted as to meet the said wants only."

In Bengal, Assam, Sind, and the Central Provinces there are none among the witnesses who belong to the Hindu priest or mohunt class.

The total number of witnesses who simply state that the use of ganja is connected with the religious customs of the people are in Bengal 96, Assam 9, North-Western Provinces and Oudh 74, Punjab 27, Central Provinces 28, Madras 36, Bombay 38, Sind 12, and Burma 2. Those who consider the observance of these customs essential are 55 in Bengal, io in Assam, 23 in North-Western Provinces and Oudh, 9 in Punjab, II in the Central Provinces, 13 in Madras, 6 in Bombay, 2 in Sind, and I in Burma ; while the number of witnesses who state that there are no such customs prevalent are 55 in Bengal, 8 in Assam, 114 in the North-Western Provinces and Oudh, 25 in the Punjab, 24 in the Central Provinces, 78 in Madras, 30 in Bombay, 15 in Sind, and 8 in Burma.

It has been alleged that the use of ganja among religious mendicants who are constantly exposed to sun and rain has beneficial effects. The objects with which it is used by these classes of people are mainly twofold—(1) to produce intoxication, and (2) to generate heat. Apart from its intoxicating effects, if the generation of the heat in the system be one of the objects which the consumers have in view, I think it would not be altogether out of place to mention here that the abolition of the drug is not likely to cause them any hardship, as in that case its place can be supplied by an innocent root called Durba (Cynodon dactylon), which is very common, and which grows throughout India. This root) if smoked in a chillum, has the wonderful effect of generating heat in the system, while at the same time the unpleasantness caused by the intoxicating power of the latter can be avoided.

Charas is very deleterious, and the use of this form of the drug is highly in disrepute. It has no connection whatever with religious and social customs of the people ; and, as it is imported from foreign country, it is quite feasible to prohibit its importation. I therefore recommend the prohibition of its manufacture, importation, and sale. With a view to save the persons connected with the manufacture and trade of charas from suffering any pecuniary loss, and the habitual consumers of charas from the inconvenience of sudden deprivation of the use of the drug, it would be advisable to give sufficient notice and allow a time before the adoption of prohibitory measures.

Although I am fully convinced of the injurious effects of ganja and the benefit which will be derived by its total prohibition, I think I would not be justified in advocating a sudden prohibition, having regard to the dissatisfaction which it may likely cause to a class of people known as sanyasis, bairagis, and fakirs, whose facilities for giving trouble are very great owing to their peculiar position and habits of life. I do not think, however, that this dissatisfaction of certain classes of people on account of the prohibitory measure in itself is likely to cause any serious annoyance to Government, but this, when added to other similar causes of dissatisfaction, might bring about discontent. It is scarcely necessary to point out the nature of the influence which these sanyasis* and fakirs still exercise over a vast number of people who have not received English education.

There are other grounds besides the one mentioned above which lead me to recommend a gradual prohibition. If, instead of adopting a sudden prohibitory measure, the Government adopt a gradual one, it will get time to institute further inquiries, should it be considered advisable, with a view to ascertain the exact physiological action of ganja. If it be found possible to refine the drugf and make it less injurious by diminishing its narcotic effect, the question would then arise whether, like opium, it would not be advisable to make a Government monopoly of the drug. If, however, on moral or other grounds this course does not commend itself to Government, it would be a question for further consideration whether the cultivation and manufacture of ganja might not be concentrated at one place under direct Government supervision. In the latter case the disadvantages of the monopoly system may be avoided, while at the same time the advantage, namely, the control of the strength of the drug, might be obtained, and the smuggling of the drug may be minimised. At present we have not sufficient means to ascertain how far the injury caused to the consumers of the drug is due to the pure drug itself, and how far to the other poisonous substances that are occasionally mixed with it. This difficulty would be removed if the entire cultivation and manufacture of the drug are brought under Government supervision. Another great advantage to be derived by the adoption of this course is, if after further consideration and investigation, as suggested above, the Government decides for total prohibition, that nothing would be more easy than to give effect to such a measure. I would therefore recommend that, as a preliminary step towards prohibition, the cultivation of ganja may be concentrated in one place, and its manufacture and sale be brought under direct Government supervision.

I would further suggest for the consideration of the Government the following :— ,

Although in the opinion of scientific men ganja does not lose its narcotic value in lapse of time, yet:the popular belief among consumers throughout India is that the drug loses its strength in time. I, however, believe it is quite possible that by exposure to air for a long time the ganja may lose its narcotic strength by a slow oxidation process. I would therefore suggest that ganja may not be allowed to be sold till after the expiry of one year from the date the crop is harvested, thus enabling the people to use it in this less injurious form.

It has come to our knowledge that some parts of the country grow stronger ganja than others. The physiological investigation concerning the various kinds of ganja grown in this country cannot be said to be complete. I would therefore suggest that, if it be actually found after due investigation that_ the drugs have different narcotic values in different parts of India,•the cultivation and manufacture of the stronger form should be discouraged and its sale altogether prohibited, the weaker ganja only being allowed to find its way to the market.

It has been elicited in our inquiry that in some parts of the country women sell these drugs. The vend of these drugs, especially through women, lends an additional inducement to the buyers to indulge in these drugs. It would be well if measures are adopted to put a stop to these practices.

In paragraph 648, Chapter XVI, of the Report it has been recommended that the licensees of retail vend should not sell these drugs to children and insane persons. It would be better in case of children to fix an age limit, say 16, and to further restrict the sale to persons who, being under the influence of ganja or some other intoxicant, have no self-control at the time. It should further be stipulated in the license that no vendor shall adulterate his drugs with dhatura seed and other poisonous stuff. A heavy penalty should be imposed for infringement of the above rules besides forfeiture of the license.

The practice of consuming the drug in the shops should be discontinued, as in some cases it gives great facilities to consumers who on account of the joint family system, out of respect to their elders, cannot dare to take it in family dwellings houses. The practice of smoking in the shops also leads to the excessive use of the drug.

In England, although heavy duties are levied on all kinds of intoxicating articles, including tobacco, and the arrangements of excise administration and control of the use of intoxicating drugs are more complete than in any other country, still the legislature of .that country very wisely kept aloof from touching the preparation and use of the weakest kind of drink—beer--for home consumption. No duties are levied there on private brewers occupying small houses not exceeding annual value, and who are brewing only for domestic use*. Though this arrangement causes loss of Government revenue to a large extent, yet, on the other hand, it, supplying the people with a less injurious kind of beverage, keeps them to some extent from the attraction of strong spirituous drink. In the same manner the Government of this country can help the cause of temperance by losing a little of its hold on a glass of sap from a palm tree belonging to a poor cultivator or a handful of leaves from a bhang plant growing spontaneously adjoining his homestead. It is greatly to be regretted that my colleagues should have thought it advisable to recommend the imposition of increased duty on bhang and the adoption of a system which would not only practically deprive the poor rural population of some parts of the country of the use of bhang leaves as a cooling beverage durin;; the hot months of the year and as a domestic medicine for men and cattle, but would also drive them to some extent to the ganja shop to satisfy their craving for stimulant, as has been already the case in the Central Provinces. In former times bhang leaves were procurable in almost all the districts of the Central Provinces, but now, probably owing to the good administration of the Excise Department of those provinces, it is a rare thing there, and more than one witness in the Central Provinces states that the people use ganja in the form of a drink because they cannot get bhang. The matter has come to this pass not only in the Central Provinces, but also in many parts of Southern India. Many experienced native gentlemen as well as Government officials are of opinion that it would be well to leave bhang alone. Bengal witness No. 25, Mr. N. K. Bose, the District Magistrate and Collector of Noakhali, says :-

" The taxation in case of bhang stems quite unnecessary."

Quotations to the above effect could be given from the statements of the witnesses, but I do not think they are needed.

It has been shown already that bhang is probably the least injurious of all the intoxicants commonly used in this country. It is to a great extent connected with the social and religious customs of the people. Its use as a cooling drink in the hot months is very common, in the central and northwest parts of India. As a domestic medicine for men and cattle, it is much in use among the rural population. The bhang plant growing wild can be found in almost all parts of Northern India. In my opinion it would not be a very easy task to bring the sale and manufacture of bhang under full control of the Excise Department of the Government without much annoyance to the people. I for these reasons recommend that bhang may be left alone for the present.

18th August 1894. SUSHI SIKHARESWAR ROY

1 "Sura-panam is also spoken of besides soma-pa nam—that is, dram-drirking as distinguished from wine drinking ; and in the Satapatha Brahmana, a son of Tvashtri is represented as haviruz three months, one of which was soma-drinker, another Sura-drinker, and a third the consumer of other things." Page 21, India: Past and Present, by Mr. Dutt.

2 Groups of these wanderers are frequently to be seen all over the country, lodging under large trees, the shady boughs of which serve as a canopy, under which they eat, drink, and sleep contentedly, a small raised hollow made of dried clay holding the fire which boils their culinary ingredients. At night they lie down for the most part on the bare ground or on little mats, with nothing softer than the roots of trees for their pillows. In this way they stroll, not only over all India, but even over parts of Central Asia, and some are known to have rambled on so far as Astrakhan and St. Petersburgh. They do not mind their privations while the liberty of their life they enjoy, and with some those distant journeys are not altogether aimless, as they carry many valuable things in their girdles in which they traffic. Begging is, of course, unavoidable to such a life, but the sanyasis 'eschew it as much as they can. Among them are to be found some very clever men."—Page go, India : Past and Present, by Dutt.

3 If, instead of seeking to stop its entry into the country, we were to direct our attention to its refinement and purification, a vast amount of good would ensue.—(The British Medical yournal, dated September 23rd, 1893.)

4 49 and 50 Vict., Chapter 18, section 3.