| - |

Drug Abuse

CHAPTER XVI.

PROVINCIAL SYSTEMS EXAMINED.

633. In Chapter XIV the Commission dealt with the general policy which, in their opinion, should regulate the excise administration in respect of hemp drugs, and in Chapter XV they have described the systems at present existing in British India. They will now offer some remarks regarding the measures necessary to give effect to that policy, and will then proceed to examine the existing systems in the light of these remarks, adding their recommendations where change of any kind seems desirable.

634. The simplest method of dealing with the subject is to farm the monopoly of vend, leaving the lessee to make his own sufficient. arrangements for a supply of the drugs and their sale to the public. This is the system (with some slight differences) which is in force in the North-Western Provinces, the Punjab, Madras, Bombay, and the minor administrations. It has the advantage of relieving the Government of all responsibility or interest in the matter beyond the disposal of the farms. It secures a preventive agency of a non-official kind for dealing with illicit sale and smuggling; and if proper care is taken to appoint respectable vendors to prevent combinations for the purpose of keeping down the price of the farms, and to license shops only when they are required by the local demand, such a system may appear to be successful and sufficient. But there are some serious objections to it. In the first place, it has the disadvantage of exercising no control over the production and consumption. Large profits do not depend upon the price being raised to the pitch necessary to check excess ; they are as easily realised by large sales at low rates. Thus consumption may very probably be unduly stimulated. Secondly, the Government acquires no accurate information regarding the extent of the production, the sources of supply, and the increase or decrease of the habit of using the drugs. The Commission think it is the duty of the Government to acquire this information. Thirdly, the system leaves the whole revenue and consequent check on consumption at the mercy of competition, which is a very unsafe regulator. And, lastly, direct taxation has already been resorted to in some cases with good results, whereas in provinces where only the license system prevails control is insufficient and taxation inadequate.

635. In the opinion of the Commission, the combination of a fixed duty with license fees for the privilege of vend constitutes the best system of taxation for the hemp drugs.

It is the system which prevails in regard to spirituous liquors produced in India, and is equally applicable to other intoxicants, in regard to which a policy of control and restriction is necessary. Unless there are special reasons to the contrary, the Commission think that the monopoly of vend should be auctioned. The special advantage of doing this lies in the fact that a method is thus secured of adjusting the total incidence of taxation to special circumstances, such as the local demand, the expense of carriage, the facilities for smuggling, the habits of the people, and the price of other intoxicants.

The danger of relying mainly on the auction system as a check on consumption is that a combination, or the absence of competition, among the vendors might at any time destroy its efficiency. The fixed duty should therefore be as high as possible, due regard being paid to the considerations mentioned in Chapter XIV, paragraph 586. When this is done, the auction of licenses for vend will come in as a valuable adjustment, and, if properly worked, will indicate whether the limit of taxation has been reached. If the proceeds of the auction sales of licenses have a decided tendency to increase, this will be an indication that the fixed duty will bear an increase.

636. But besides that which results from adequate taxation, another method of restricting consumption is available to the Government in the limitation of the sources of supply. And the most effective way of doing this, at all events in the case of ganja, is to prohibit cultivation of the hemp plant, except under license, and to grant licenses for cultivation in such a way as to secure supervision and registration of the produce. Unless this is done, it is impossible to have any idea of the extent of consumption. The opinions formed from time to time in regard to this matter in provinces where cultivation is not controlled are mere guesses doomed to be falsified. It is of the greatest importance that this control should be exercised. In regard to charas, the only way of limiting the supply is by taxation, and the conditions of the trade are such that the supply can be completely regulated by the application of this method. Where the hemp plant grows spontaneously in abundance, the supply of bhang cannot be regulated, but in other places there is no reason why its cultivation should not be placed under the same restrictions as that of ganja, and a direct duty, which must be light in proportion to the facilities for importing the drug free of charge, imposed. The subject will be referred to again further on.

637. Another most effective way of reducing the sources of supply is by keeping the number of licensed shops to the lowest limit compatible with meeting the real demand. The increase of shops or failure to reduce them has often been pointed out as an error committed by individual district officers whose aim was too much to raise revenue. The impropriety of this and its danger cannot be too strongly insisted upon. The matter is one which should be kept constantly in view by the Local Governments and by the Government of India.

638. The Commission do not, however, advocate any attempt to restrict the supply of the drugs by an artificial check, such as limiting cultivation of ganja or import of charas, with reference to an ascertained or computed average demand. It is not for the Government to determine how much of the drugs should be consumed. Its function is to exert pressure, but not to fix limits ; to regulate the conditions, but not the actual quantity ; and it is far better that, subject to thoSe conditions, the laws of supply and demand should not be interfered with.

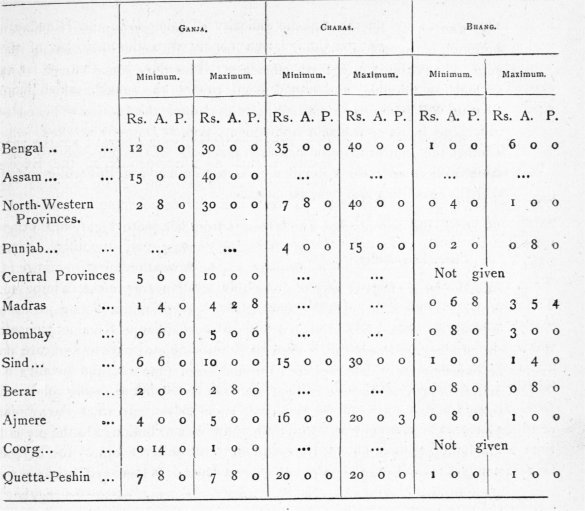

639. The incidence of taxation in different provinces ought not ceteris paribus to vary greatly. The following table shows the retail prices per ser prevailing in the different provinces

The figure given as the maximum for ganja in the Central Provinces is not the true maximum. It is " the average retail price in most districts for small quantities of ganja." The maximum must, therefore, be higher. In Jubbulpore, the Commission found that in some shops ganja was selling at Rs: I2 per ser. The maximum for the province is not available. A maximum quotation of 4 annas per tola, equal to Rs. 20 per ser, is given for Ganjam in Madras : this may be Rajshahi ganja. Bhang is said to reach a maximum price of Rs. to per ser in the same district. In Malabar, Vellore ganja is said to reach 4 annas per tola, but the maximum price in North Arcot is 4 pies. Wynaad ganja in the same district is said to reach a maximum price of 2 annas per tola. With these exceptions, no district shows a higher maximum price than that given in the statement.

It is evident that if the systematic treatment advocated by the Commission is to be applied, some means must be taken, especially in regard to ganja, of removing the extraordinary inequalities disclosed by this comparison. Up to year 1892-93, notwithstanding the high price of Rajshahi ganja, the cost of the daily average allowance of liquor to the habitual consumer in Bengal is, according to the memorandum, much higher than in the case of ganja. Judged by this test, there is room even in Bengal for increased taxation. A fortiori is this the- case in other provinces except Assam. No doubt the quality of the drug varies in different provinces, but there is nothing in the analysis of the different kinds of ganja which points to such marked discrepancies in the price. And the general conclusion which must be drawn from these figures is that in all the provinces, except Bengal and Assani, taxation is totally inadequate to the due restriction of consumption. The same may be said of charas. As regards bhang, many witnesses are of opinion that there is no need to impose the same restrictions upon its consumption as in the case of ganja and charas, and the difficulty of doing so in the Himalayan region is considerable. But the Commission concur with the majority of the witnesses in thinking that the same general principles apply, and that, so far as may be possible, this product of the hemp plant should be brought under more efficient control and taxation.

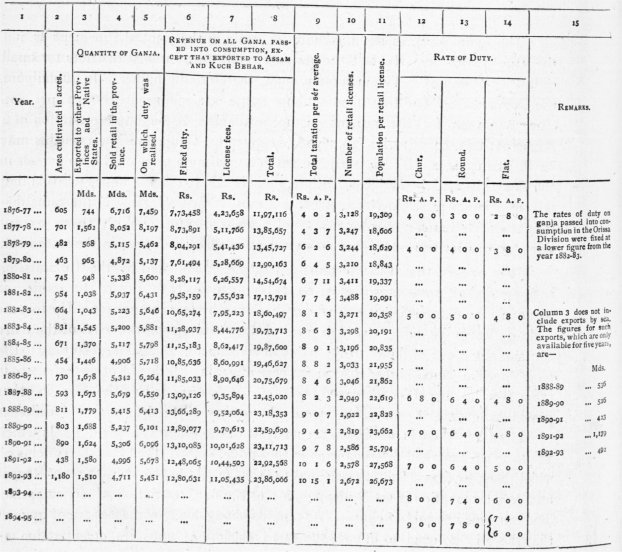

64o. A historical sketch of the ganja administration in Bengal from the year 1790 will be found as an appendix to the Excise Commissioner's Memorandum. From the first the object of the measures taken was "to check immoderate consumption and at the same time to augment the public revenue." Up to the year 1853 hemp drugs were taxed by means of a daily tax on their retail sale paid monthly. From 1824 to 1847 it was usual to farm out the excise revenue of entire districts. From 1853 the daily tax was abolished, and a duty of Re. 1 per ser was imposed. The retail vendor had to pay the full amount on a specified quantity in each month whether he took it all or not. In 186o-61 a fixed fee of Rs. 4 per mensem was levied-for each ganja license, in addition to the duty at the prescribed rate, on all quantities passed to the shop for retail sale, the rule regarding the quantity to be taken by each shop being withdrawn. This was the beginning of the combined fixed duty and license fees system which at present exists. In 1876 the system of selling licenses by auction was introduced, and this has continued to the present time. The following table shows the operation of the action taken by the Bengal Government since the time when the auction of license fees was introduced :--

641. This table shows that up to the year 1892-93 on five occasions some increase was made in the rate of fixed duty. The revenue steadily increased, until at the end of the period it was double as much as in 1876-77 ; notwithstanding this, the number of retail licenses after the first period of six years steadily diminished up to the year 1891-92, though in the following year there was an increase. The result is that the number of the population per retail license increased by 38 per cent. in the whole period. The increase in the total average taxation per ser of the taxed drug increased from Rs. 4-0-2 to Rs. to-15-i. As regards the area cultivated (column 2), it has to be remembered that these figures represent the growth of the plant for consumption in Assam, the North-Western Provinces, and some Native States as well as Bengal. The figures in column 4 represent the ganja actually consumed in Bengal, which has decreased largely since the first two years, and since then has been nearly stationary.

In addition to the above facts, the evidence before the Commission tends to show that, except in Orissa, where the Garhjat ganja competes with the Rajshahi ganja, smuggling does not prevail in any part of the province ; also that ganja is still the cheapest form of intoxicant, and that there is no evidence to lead to the belief that it is being displaced in Bengal by more noxious stimulants. The Bengal Government seems to have kept in view with the most successful results the principles which have been enunciated in Chapter XIV, paragraph 586, of this Report as essential to an efficient excise system, and to have intervened, when occasion demanded, to restrict the use of the Rajshahi ganja by administrative control and enhanced taxation. The effect of the enhancements which have been made since the year 1892-93 cannot be gauged, but the Commission have no hesitation in saying that this part of the excise administration in Bengal is being most carefully and ably supervised.

642. The weak points in the Bengal administration are—

(1) The defective arrangements for storage of the Rajshahi ganja.

(2) The smuggling into Orissa of the produce of the Tributary Mahals.

643. The Bengal Excise rules provide that the cultivator must send into. the public gola all the ganja he manufactures, and private golas are only permitted in the case of a cultivator who can satisfy the supervisor that he has a secure private place of his own. It has been shown above (paragraph 595) that there is no public gola for the storage of the crop, and that all the produce is stored in private golas. The opportunity for smuggling thus afforded has not escaped the notice of the authorities. In his report on the cultivation of and trade in ganja, 1877, Babu Hem Chunder Kerr (paragraph IA dealt with the question, and recommended the absolute prohibition of private storage and the establishment of public godowns where the drug might be warehoused in bond. He was of opinion that six storehouses 125 feet X 20 feet, three of which should be at the sadar station of Naogaon and three at three outposts, would be sufficient to warehouse the crop. The Board of Revenue did not support the proposal, remarking that it would involve a very radical change in the existing system, and would also necessitate a very considerable expenditure on the part of Government in the construction of the necessary warehouses, The absence of any evidence as to extensive smuggling was mentioned as obviating the necessity for the measure. In 1892 the Board were of opinion that the objections to public golas appeared to be insuperable. Mr. Lyall in his evidence says that the storage arrangements can be improved, but that under existing circumstances it would be impossible without enormous expenditure to have a public gola. Mr. Gupta, Excise Commissioner, says that the difficulty of having a public warehouse is that the ganja stored in it would consist of numerous parcels, all belonging to different individuals, and this would lead to much confusion. Again, the drug has to be frequently aired, turned out, and handled in order to keep it in good condition, and it is next to impossible to secure this periodical examination when the ganja is stored in public golas situated at a distance from the houses of the cultivators." He therefore considers the scheme " impracticable," on which Mr. Lyall notes : " Rather, I would say, too costly." Mr. Price, Collector of Rajshahi, does not recommend public golas because Government servants would not take care of the ganja as the owners would. But he does not think there would be any great difficulty if there were several Government golas situated in central places, though he does not think the cultivators would view the change with favour. He concludes by saying that he sees no great objection to the plan ; and adds " You cannot have a perfect system without Government golas." Babu Hem Chunder Kerr retains his former opinion in favour of the system, which is also advocated by Ganendra Nath Pal, Sub-divisional Officer, Naogaon, and Abhilas Chandra Mukharji, Excise Inspector. The Commission have formed the opinion that the objections are not insuperable, and that the system of Government storehouses should be introduced. The example of the Central Provinces system seems to prove its practicability, and they are of opinion that it would have the effect of bringing about the speedy conclusion of bargains between the cultivator and the wholesale dealer, in which case the main difficulty would be removed. The expense of erecting several godowns should not, in their opinion, operate to prevent the measure considering the very large revenue at stake and the great desirability of removing the existing temptations to illicit dealing. The matter should, however, be left to the discretion of the Local Government.

644. The smuggling of ganja from the Tributary States of Orissa into British territory has a long history, and more properly belongs to the general subject of excise administration in Native States, which will be dealt with further on.

645. The proposal of the Excise Commissioner to abolish flat and round ganja and have only chur is one that deserves notice. He explains rather more clearly in his evidence that what he advocates is not the compulsory production of chur, but the adoption of the chur rate of duty which is the highest for all ganja, which would result in the elimination of stick from the produce, and consequent reduction of the whole stock to chur. There are obvious advantages in having one rate of duty, but other considerations enter into this subject, such as the question as to the form in which the drug can best be packed and transported without deterioration. The experiments which are being conducted in connection with this question are still incomplete. The Commission feel that the matter is one for the Local Government to decide. It is mentioned here because it would materially reduce the bulk of the produce and make the introduction of public golas more easy of accomplishment. The plan is also advocated by some subordinate Excise officers and Deputy Collectors.

646. The present system of ganja administration in the Central Provinces has been in force since 1882-83, previous to which there were several changes, which may be briefly recapitulated. In 1871-72, the first year during which Act X of 1871 was in force, the monopoly of vend of drugs (which included madak) was put up to auction for each district as a whole, or for smaller areas, and knocked down to the highest bidder. The contractors were free to make their own arrangements for obtaining the drug from cultivators, and cultivation was free. In 1873-74 the Local Administration had to consider complaints by the retail contractors to the effect that the extensive cultivation of ganja for home consumption by private individuals seriously interfered with their profits, and prevented them from paying to Government as high a revenue as they otherwise might. Meanwhile the Government of India had issued instructions to all Local Governments to discourage the consumption of ganja and bhang as far as possible by placing restrictions on their cultivation, preparation, and retail, and imposing on their use as high a rate of duty as could be levied without inducing illicit practices. Accordingly, in April 1875, rules were introduced prohibiting cultivation except under license, for which the levy of an acreage fee was authorised, and embodying other provisions for inspection of stocks and licenses to cover the possession of the produce until its purchase by the licensed vendor. The acreage fee was fixed soon afterwards at Re. 1, and in 1876-77 a special penal fee of Rs. to per acre on unlicensed cultivation was introduced. These acreage fees were, however, pronounced illegal by the Judicial Commissioner in 1878, and new rules were framed providing for the storage of all ganja in Government godowns or in authorised private storehouses and for levy of duty on the drug when removed. The duty was fixed at Re. i per ser. Difficulties were experienced in working these rules, the cultivators not being able to dispose of their produce to the licensed vendors. The wholesale vendors held aloof, feeling uncertain of the effect which the enhanced duty might have on consumption, and the retail vendors would not purchase direct from the cultivators. The 'Local Administration accordingly purchased nearly the whole crop, amounting to some 6,856 maunds, at a cost of nearly Rs. 50,000. The Government of India, however, objected to the creation of a Government monopoly of ganja; so in 188o-81 the monopoly of wholesale vend for the province was granted to a single individual, who agreed to pay a duty of Rs. 2 per set- on all ganja sold by him to retail vendors, and to supply them with the drug at Rs. 3 per ser. It was contemplated in the agreement that the price might be raised by increments of 4 annas to Rs. 4 per ser, and the duty by increments of 3 annas to Rs. 2-12 per ser, within the year 1880-81. At the same time the system of auctioning the monopoly of retail vend by circles was done away with, and monthly licenses were issued at fixed rates, varying according to the size of the town or village, and without limit as to the number of licenses existing in one place. This system, however, was abandoned in the following year, and the auction system was again for the most part introduced. This was the origin of the system of monopoly of wholesale which exists to the present time in the Central Provinces. Since 1882-83, by which time Act XXII of 1881 had become law, the wholesale monopolist has been called upon to pay a certain amount per-ser in addition to the direct duty of Rs. 2 per ser, the rate varying in different districts and being generally determined by tender. Such tender is limited by the necessity of supplying retail vendors at Rs. 3 per ser to an amount per ser less than Re. t. The object of this measure was to fix the difference between the duty on the drug, Rs. 2 per ser, and the price at which it was to be sold to retail vendors, Rs. 3, at a figure considerably in excess of the cost price of the drug, and to put up the gross profits thereby secured to the wholesale vendor to auction in the form of tender. It was thought that this would practically raise the direct duty in the districts where the cost price of the drug was least, and so equalize prices throughout the province. Cultivation in British territories has been concentrated, and since 1891 it has only been allowed in the Khandwa tahsil of the Nimar district.

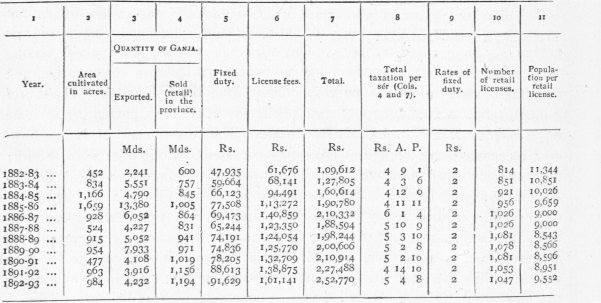

647. During the changes above described there were great fluctuations in the area of cultivation, but the revenue steadily increased. The amount of consumption is not available. From 1882-83 the statistics are more complete, and the tabular statement subjoined will show the progress of the administration in regard to exports and consumption of ganja, the amount and rate of taxation, and the number of shops. Column 2 contains the figures as accurately as possible for the area cultivated ; the table appended to the Excise Commissioner's memorandum gives the areas for which licenses were taken out, which were generally in excess of the area actually cultivated. Column 5, showing the fixed duty, represents the Rs. 2 per ser duty levied on all ganja issued to the retail vendors of the province. Column 6 represents retail license fees, and the amounts, called wholesale license fees, obtained in accordance with the tenders of wholesale vendors :-

648. It will be seen from this statement that the fixed duty of Rs. 2 per ser has not been raised since 1882-83. As above remarked, an increase was contemplated as far back as 188o-81. In 1887 the Local Administration declined to raise the duty, the principal reason assigned being that the effect would be to lower the bids for retail vend monopolies. The total taxation per ser of consumption has slightly decreased since 1887-88. The local consumption shows a tendency to increase. The number of shops per head of population has on the whole increased ; and, although the revenue has increased, this is due partly to increased consumption, and partly to keener competition in the auction sales of licenses.

The basis of good administration has been laid, but progress has not been secured, and to this result it is essential that attention should now be directed.

649. One important defect of the system is that exported ganja is very lightly taxed. In regard to this subject, the Excise Commissioner in 1887 remarked : " The part played by the Khandwa store as an entrepot for the supply of the ganja demand of those provinces (the Central Provinces) is quite insignificant when compared with its use as a mart for the convenience of foreign purchasers. To it throng traders from Bhopal, Indore, Gwalior, Rutlam, Dhar, Jodhpur, Udaipur, Rewa, Panna, Baroda, and other States of less note ; and licensed vendors from the North-Western Provinces compete with contractors from Berar for the purchase of the cultivators' stock. Between 6,000 and 7,000 maunds of ganja have on the average of the last four years been annually exported from Khandwa to other provinces and Native States." Since these words were written the permit and registration fees have been imposed, and all the exported ganja pays something before being removed for export. But besides a small fee for storage, Government licensed vendors exporting to the North-Western Provinces or other British provinces only pay Re. t per maund by way of registration fees, and foreign purchasers only pay Rs. 2 per maund for permit and registration fees. An instance is here afforded of the necessity of the systematic treatment advocated in Chapter XIV, paragraphs 588 and 59o. A large amount of ganja which leaves the Khandwa store is insufficiently taxed, and it is absolutely necessary that arrangements should be made both with British provinces and with Native States to ensure its being adequately taxed in future. Whether the duty should be levied at the place of production or at the place of consumption is a matter of detail : the main point is that it should be levied somewhere before it reaches the consumers.

650. The Commission cannot regard the possible falling off in retail license fees as any reason for refusing to raise the duty on the Khandwa ganja consumed in the province unless such a falling off produces other consequences detrimental to the Administration. Caution is always necessary in raising the duty lest it should lead to illicit practices, and the circumstances of the Central Provinces require special watchfulness in this respect. The difficulties in the way of increasing the duty. owing to the much lower price of the drug beyond the borders of the province are brought out clearly in the Excise Commissioner's memorandum. But making all allowances for these difficulties and for the fact that the Khandwa ganja is inferior to that produced at Rajshahi, the Commission are of opinion that the rate might safely be raised.

651. The question, however, is one which is intimately bound up with the whole system of monopoly existing in the Central Provinces, and this system demands close examination.

It has arisen, as has been shown, from special circumstances. Its main features are that Government interferes at the point where the ganja passes from the wholesale to the retail vendor to fix the price at Rs. 3 per ser, and that the monopoly of wholesale vend is given to a small and selected number of persons who tender for payment of duty at Rs. 2 per ser plus as much of the margin between Rs. 3 and Rs. 2 as can be got from them. There can be little doubt that, apart from the difficulties above referred to, the system itself may have operated against a rise in fixed duty. The interference in the natural operation of the laws of supply and demand has rendered it more difficult for the Government to gauge for itself the necessity for increasing the direct duty. And it may be remarked that, in spite of the fact that the direct duty has not been raised, the receipts from licensed fees have not very materially increased, and therefore, while Bengal has doubled its taxation on the ganja consumed, the Central Provinces taxation has remained stationary. The cause of this may partly be found in the different circumstances of the two provinces. Except in Orissa, the question of smuggling has been set at rest in Bengal. In the Central Provinces the arrangements with the Tributary States which were undertaken with this object have only just been completed, and it may have been considered advisable to postpone any increase in the duty until this should have been done. But even allowing for this, the Commission think there is reason for attributing to the different systems, at all events in part, the widely different results obtained.

652. The advantages claimed for the system are—

(a) that it enables the retail vendor to know what he is about, and makes him independent of combinations and caprice among the wholesale vendors. This would tend to induce him to bid more for his license :

(b) that it enables Government to secure part of the wholesale dealer's profits :

(c) that it tends to equalize the price to the consumer all over the province.

The first two of these are not in themselves of any great importance. The main object is to secure that the drug is adequately taxed ; and if, as appears possible, the license fees instead of being raised are kept down by the present system, while obstacles are placed in the way of raising the fixed duty, the advantage is more than counterbalanced. And as regards the third, it may be observed that the check imposed upon the price of the drug by fixing the price to be paid for it by the retail dealer may very possibly keep the price to the consumer unduly low in some districts, while in others, where the opportunities for smuggling are greater, there is no adequate test of its suitability.

653. The principal disadvantage of the system appears to be that it imposes upon the Government the responsibility of taking into consideration several factors the precise value of which it is difficult to estimate, and the effects of which are better gauged by the unimpeded competition arising from the auction of the privilege of retail sale. And it seems possible that the present system may operate to a certain extent in checking the cost of production and the profits of the cultivator. If these had free scope, they would probably tend to raise the price of the article. Moreover, the profits of the wholesale vendor as such are kept down to such a low figure that it is almost certain that he recoups himself in many cases by taking out licenses for the retail vend. The system thus encourages a combination of interests which is not generally desirable. The subject is unfortunately not treated in the memorandum, but in jubbulpore the Commission ascertained that out of 71 retail shops, zo were held by the wholesale monopolist. The status of the latter is such as to give him practical command of the situation, and the inference is almost irresistible that he will make use of this power to acquire for himself some of the profits attaching to the retail business if dissatisfied with the profits of the wholesale business. Viewed in this light, the limitation of the price may be to a large extent inoperative.

654. Upon the whole it appears to the Commission that any attempt to regulate the price of ganja otherwise than by a combined system of fixed duty and auction vend of monopoly of retail sale in tracts differently circumstanced is a mistake. It amounts to an interference either too great or too little. A Government monopoly under which, through the agency of Government officers, the drug would be offered to the public at a maximum price would be a simple arrangement. This has been shown not to be the best system for ganja (Chapter XIV, paragraph 589). The alternative is to levy a duty which must be regulated according to experience, the maximum being determined by those general considerations which have been elsewhere explained, and leave the supply unhampered, except by such check as is afforded by the auction of monopoly of retail sale. The latter affords the necessary adjustment for disadvantages pertaining to different localities, such as unusual cost of carriage, facilities for smuggling, etc. If on account of such disadvantages the rate of duty needs to be reduced, there is nothing to prevent the adoption of special rates of duty for particular tracts.

In recommending an increase of duty, therefore, on Khandwa ganja, the Commission are prepared also to recommend that the rule under which ganja is supplied by wholesale to retail vendors at a fixed price should be abolished, and that wholesale vendors should not be required to pay fees for their licenses.

655. In one respect the Central Provinces system is more efficient than that of Bengal, viz., the storage of the produce. No difficulty seems to have occurred in these provinces in bringing all the ganja to a central godown at Khandwa. This is probably because the establishment of the godown has obliged the cultivators to come to early terms with the wholesale dealers or their agents. Mr. Robertson, Deputy COmmissioner of Nimar, says : " The agents buy up the ganja on their own account as a speculation frequently while the crop is standing. The whole outturn thus passes into the hands of about a dozen men, who are then able to run up the price at the Khandwa storehouse to all except the wholesale vendors, by whom they have been specially retained. The existence of the ' corner' in no way affects the vend of ganja, so far as this province is concerned. The wholesale vendors have to supply the retail vendors at Rs. 3 per ser, so that the latter, and through them the consumers, are not affected. But wholesale vendors from other provinces undoubtedly find it difficult to make purchases at Khandwa. " The Commission think that a system which leads to the speedy disposal of the crop by the cultivators to the wholesale vendors is desirable, but the monopoly of wholesale vend seems to be in this province in too few hands, whereby combination against a rise of duty is facilitated. Subject to the adoption of the measures advocated in paragraph 654, the Commission recommend that wholesale licenses should be more freely granted without charge as in other parts of India, the selection being carefully made by local officers according to requirement.

656. If the suggestions made in paragraphs 643, 649, 650, 654, and 655 of this chapter are accepted, the systems of Bengal and the Central Provinces will be practically assimilated. And apart from the fact that the system advocated appears to possess the greatest advantages, this result is in itself most desirable.

657. The statistics for the North-Western Provinces are regarded by the Excise Commissioner as very defective so far as regards the amount of imports and exports. In the absence of any fixed duty, and with a revenue determined solely by the license fees, no provincial record of the traffic has been kept up. Mr. Stoker is not confident that allowance has been made for transfers from district to district, and he thinks there is much risk that the same drugs may have been counted twice, and the provincial total thus exaggerated. Moreover, licenses for the sale of the different kinds of drugs have not been sold separately. All that can be gathered from the statements furnished is that the total amount of the license fees has increased by about 75 per cent. in the last 20 years and the number of retail licenses by 5o per cent., and that the imports and consumption of ganja seem to be on the increase. The excise ganja of Bengal is being displaced by the drug frdm the Central Provinces and Native States, which is almost wholly untaxed, and this is one of the weak points in the North-Western Provinces administration as pointed out in Chapter XV, paragraph 609. The total revenue from license fees is in 1892-93 Rs. 7,04,788, but from this would have to be deducted the amount due to licenses for the sale of charas and bhang which cannot be ascertained. At a rough guess, it may be put at one-third, leaving Rs. 4,70,000 due to ganja. To this must be added the duty on Bengal ganja levied in Bengal (about Rs. 1,12,600) and the registration fees at Re. 1 per maund levied on Central Provinces ganja at Khandwa, making a total of about Rs. 6,00,000, or Rs. 3-2-3 per ser on all imported ganja reckoned on an average of 4,774 maunds. On the whole this does not appear to be a very inadequate incidence of taxation, but it must be remembered that there is no control of production in the province, and that the taxation on the different kinds of ganja imported is very unequal. The number of shops is very large, nearly double in proportion to population of that which is found in Bengal. There can be no doubt that in this province more control is necessary, and some measures are urgently required for reducing the taxation of the different kinds of ganja which are brought into the province to some kind of uniformity. The need of remodelling the system has been fully recognised by the officers in charge of the excise ; and the proposals of the Excise Commissioner, which have the support of the Member of the Board of Revenue in charge of Excise, include the following measures

(1) Prohibition of cultivation except under license.

(2) Prohibition of manufacture of ganja.

(3) Establishment of bonded warehouses, with control of storage and issue of ganja.

It is also proposed to control the import of ganja, and to impose an import duty at first of Rs. 5o to Rs. 8o per maund on pathar ganja from the Central Provinces and Native States, to be increased by degrees. For this purpose an amendment in the law will be required. Subject to the remarks which will be found further on (paragraph 679), the Commission agree in these proposals.

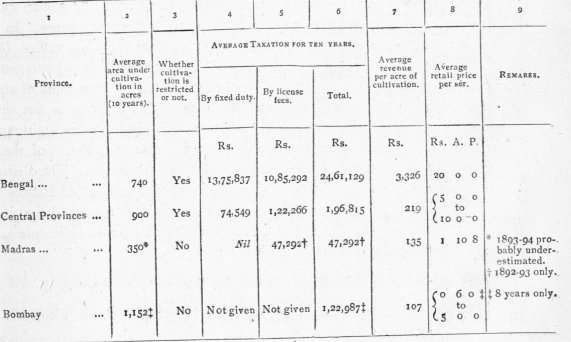

658. In Madras and Bombay the general opinion among local officeri appears to prevail that no changes are necessary, though the Commission have reason to believe that these Governments recognise the impossibility of continuing the present state of affairs in view of general considerations affecting the whole of India. A seizure of 14 maunds 24 sers of Madras ganja imported by sea to Calcutta was made in January 1894. When the Madras Collector of Customs was communicated with and asked to enquire full particulars and take action if he considered it necessary, he replied to the Calcutta authorities asking under what law he was desired to interfere. The Madras Act contains full provisions regarding the import and export of drugs ; but these provisions have not been extended to the province. In view of the illicit imports into Burma from Madras, regarding which there is ample evidence from the former province, of the complaints from Mysore which are mentioned in Chapter XVII, and of the cheapness of the drug, there can be no doubt that reforms are urgently required. The system in Bombay is somewhat more formulated, but in view of the large amount of ganja produced, and the still lower price of the drug in the producing districts, there is no less need of an improvement in the system of administration. The annexed table gives a comparative view of the cultivation and taxation of ganja in these provinces, and in Bengal and the Central Provinces. The only comparison which can be made is that of total taxation per acre of reported cultivation, because the areas of cultivation and totals of taxation are the only figures on which any reliance can be placed in these two presidencies :—

659. The Bengal figure in columns 4, 5 and 6 represents nearly the whole of the revenue levied on all the ganja produced on the area given in column 2, as the Assam and Kuch Behar duties, which are not levied in Bengal, have been added.

The only item which cannot be added is that portion of the North-Western Provinces license fees which is due to the sale in those provinces of Bengal ganja. If this is calculated according to the proportionate amount of such ganja, it would not materially affect the calculation. If a similar calculation is made to determine the amount of the license fees due to the sale of Khandwa ganja in the North-Western Provinces, about Rs. 1,57,000 would have to be added to columns 5 and 6 of the Central Provinces figures, and the result of this will be to raise the average revenue per acre of cultivation in column 7 from Rs. 219 to Rs. 393. Some of the Khandwa ganja also finds its way into Bombay and Berar and other tracts, and pays duty there in the form of license fees ; so the average per acre of"Rs. 393 is still under the mark, but in any case the taxation thus calculated is very much less than in Bengal.

On the other hand, the average revenue per acre for Madras and Bombay is probably over the mark, as the amounts in column 6 represent the license fees paid for all the hemp drugs and not ganja only ; and in the sales effected under these licenses is included a certain amount of ganja, at all events in Bombay, imported from other provinces. Against this, however, must be set the fact that both the presidencies export ganja,--in Madras to the extent of about one-seventh of the total produce, and in Bombay to the extent of more than one-half. But as the bulk of these exports goes to Native States, or is exported by sea, no revenue is realized therefrom, and the figures of column 7 are therefore on the whole probably in excess of the true figures. The general conclusion is that as compared with Bengal, or even with the Central Provinces, the taxation of the ganja produced in Madras and Bombay is very light.

660. In the Madras Presidency various proposals have been made from time to time for introducing some control into the excise administration in respect of hemp drugs. In 1886 a circular was issued to all Collectors by the Commissioner of Salt and Abkari calling for information as to the extent and nature of the trade in these drugs. In this circular it was suggested that for the present it would probably suffice (a) to forbid cultivation except under license, which would be granted free of payment ; (b) to prohibit manufacture except •under license ; (c) to sell the monopoly of manufacture and vend by districts or taluks as might appear best, licenses for manu' facture and retail vend being granted at the Collector's discretion in such number as might appear requisite as in the case of the opium farms. Most of the officers consulted recommended the adoption of these proposals. The Board of Revenue, although they considered that the information collected showed that the consumption of intoxicating drugs was very limited, remarked that it was clearly the intention of the legislature that cultivation should be licensed, and they made the following proposals to Government : —

(a) to prohibit cultivation except under license to be granted free ;

(b) to restrict possession by persons other than licensed wholesale and retail vendors ;

(c) to grant free licenses to wholesale dealers ;

(d) to put up to auction licenses for retail sale ; and

(e) to impose a pass duty.

In view, however, of the indefinite and uncertain information obtained regarding the extent of the traffic in the drug and the limited nature of the consumption, the Madras Government came to the conclusion that in most parts of the Presidency no restriction was called for, but remarked that it was prepared to extend the provisions of the Abkari Act relating to intoxicating drugs to limited areas on adequate cause being shown.

Experience, however, showed that the demand for the drugs was considerably larger than was suspected, and that the competition in certain districts for the privilege of vend was very keen. Accordingly the licenses for retail vend were sold by auction, with the result that the revenue from this source rose the first year from Rs. 8,8o5 to Rs. 54,989. No further measures for controlling cultivation or restricting consumption were taken. The Board again considered the question of limiting the legal possession of the drug, which had been advocated by the majority of the Collectors, but came to the decision that restrictions on the cultivation of the plant should precede those on possession, and their objections to revising the idea of licensing cultivation appear to have been (a) that this would involve the taking out of a license by every person who had a plant or two in his garden ; and (b) that it would have been necessary to make a large increase in the number of shops in order to meet the legitimate demands of consumers. It is not clear why the Board changed their views regarding prohibition of cultivation which they had previously recommended. And the number of shops existing in Madras is under the existing arrangement manifestly inadequate, being one for every 144,781 of the inhabitants. Considering that the consumption of the drugs in Madras is found to be much larger than was suspected, and that the propriety of introducing more control into the administration has for several years been recognized, the Commission are of opinion that the needed reforms should be no longer delayed.

661. The system in Bombay, which was introduced in 188o, does not seem to have been brought under discussion since that time. The Commissioner of Excise states that the subject attracted little attention till the Commission was appointed. The Commissioner of the Northern Division says that the system seems to have grown up in a haphazard way. The subject has been treated mainly from the revenue point of view, and the control exercised has not been strict. At the same time the area of regular ganja cultivation in Bombay seems to be considerably larger than in any other province ; and if measures with a view to restriction in consumption are necessary anywhere, they certainly appear to be so in this Presiden cy.

662. The Commission on a full review of the whole circumstances connected with the ganja administration have framed the opinion that cultivation of the hemp plant for the production of narcotics in Madras and Bombay should be prohibited except under license, and that the licensed cultivators should be restricted to a limited area as in Bengal and the Central Provinces. They are of opinion that no greater difficulties exist in this respect than have been already overcome in these provinces. A few remarks are offered in justification of this view.

663. First.—In Madras and Bombay, as was formerly the case in Bengal and the Central Provinces, the regular cultivation is already confined to limited areas. There is practically scarcely any regular field cultivation of ganja except in the Kistna and North Arcot districts of Madras and the Ahmednagar and Satara districts of Bombay ; and the prohibition of cultivation in other districts will involve no serious difficulty. And though the ultimate inclusion of all the ganja cultivation in an area more circumscribed than that of two whole districts is desirable and probably feasible, still the limitation even thus far would be a considerable step in the right direction.

664. Secondly.—If it be objected that the prohibition of occasional cultivation of a few plants in the private gardens or enclosures of individuals will be difficult to enforce, to this the Commission would reply

(1) This difficulty has been overcome in Bengal, Assam, and the Central Provinces, in parts of which, as abundantly established by the evidence taken by the Commission, this sporadic cultivation was equally prevalent.

(2) The difficulty is not so great as it seems ; for whereas at first sight it seems that it would be necessary in order to enforce the prohibition to increase establishments and exercise vexatious interference with the people, such has not been found from experience gained in other provinces to be actually the case. The difficulty of concealing the plant and the evidence of illegality involved in the mere existence of a prohibited-plant in occupied lands, coupled with a legal prohibition, has in fact sufficed almost to exterminate such growth in tracts where ganja is produced with a minimum of prosecutions and penalties.

665. Thirdly.—If it be objected that the wild hemp plant growing in unoccupied lands is so plentiful that, even if the prohibition against cultivation is successful, ample opportunity will still be found to bring a large amount of ganja into the market from this source, to this the Commission reply—

(1) That the ganja derived from such spontaneous growth, untended and unimproved, is so inferior as to obviate all likelihood of its competing with the cultivated ganja.

(2) That wild hemp in the strict sense is not found in tracts removed from human habitations, past or present ; and the amount of ganja capable of being smoked which can be procured from such growth will not interfere with the success of the proposal.

666. Fourthly.—If it be objected that the ganja produced in Native States adjoining the Madras and Bombay Presidencies cannot be kept out of the province, and that this fact alone vitiates the scheme, to this the Commission reply—

(1) That even if this be so, the same may be said of the provinces where cultivation is controlled ; and while the arrangements of these provinces are, no doubt, affected by the proximity of Native States, they are nevertheless sufficiently successful for practical purposes.

(2) That there is nothing to prevent the Government from entering into negotiations with the States (as has been done in the case of the Central Provinces, apparently with marked success) for mutual co-operation in the interests of the excise revenue, and the Commission (vide Chapter XVII) are prepared to recommend that this should be done.

667. It will be desirable to analyse the evidence on this point in both presidencies. Several witnesses in Madras speak of the needlessness of controlling cultivation, but on this point it cannot be expected that they should take a sufficiently wide view, as the interests at stake are larger than those of individual districts. The only witnesses who consider the measure impossible are—Mr. Sewell, Collector ; Mr. Mounsey, Collector ; Mr. Wiliock, Collector (as regards the Agency tracts) ; and Mr. Taylor, Manager, Jeypore Estate (as regards the Agency tracts) ; two Deputy Collectors ; and a Missionary.

On the other hand, there is a much larger consensus of opinion that control is feasible. The Hon'ble Mr. Crole, Member of the Board of Revenue, in charge of Excise, says : " If you were to order the stoppage of cultivation of hemp or even rice, it would be done. There would be no difficulty in having the order carried out. The people would stop the cultivation : they are quite amenable. It would be stopped without the necessity of espionage and interference, but there would always be the risk of false charges." Mr. Merriman, Deputy Commissioner of Salt and Abkari, says : " There is a goon deal of backyard cultivation which is untaxed. It would be desirable to stop the sporadic cultivation if feasible. I think we could do this. I think it would be far simpler to issue an order stopping cultivation, and that would be far easier than attempting to tax it. I believe this cultivation could be stamped out by the mere issue of the order ; and, supposing that there were reasonable facilities for consumers obtaining the drugs, the dissatisfaction would not be great." Mr. Benson, Deputy Director of Agriculture, says that " prohibition of cultivation would not harass the people, as those affected would be so few ; and it would, I think, within a short time accomplish its object." Mr. Levy, Acting Deputy Commissioner, Salt and Abkari, thinks " the cultivation of the hemp plant, and the manufacture and possession of the drugs therefrom, should be brought under thorough control." Mr. Bradley, Collector, thinks that, except in the Wynaad, prohibition of cultivation would be possible in Malabar, and could " be generally carried out without much interference with the people, but would be hardly possible in the jungly parts." He thinks that for ordinary tracts the present abkari staff might be sufficient to secure compliance with the order, though he does not guarantee this.

Other advocates for the control of cultivation are—Five Deputy Collectors, one of whom, Mr. Azizuddeen Sahib Bati, in North Arcot, says that a prohibitive order would have the effect of stopping cultivation without any great interference ; two Deputy Conservators of Forests, three Tahsildars or Acting Tahsildars, the Hon'ble Rai Bahadur Sabapathy Mudeliar, Raja K. C. Manavedan, three pleaders, five missionaries, and four others, viz., a municipal chairman, a zamin-• dari manager, a cashier, and a sarishtadar.

668. In Bombay, though several witnesses say that further control is unnecessary, three of whom are under the impression that licenses are already required for cultivation, there is no opinion adverse to its restriction- on other grounds. The following officers see no serious objection to restriction of cultivation :—Mr. Vidal, Chief Secretary to Government ; Mr. Reid, Commissioner ; Mr. Campbell, c.I.E.; Collector ; and Mr. Ebden, Collector of Ahmednagar,

Mr. Monteath, Collector, though he thinks there is no need for controlling cultivation, is of opinion that the time has come for putting the drugs on the same footing as alcohol and opium. Three Deputy Collectors are in favour of control ; also two mamlatdars, an inamdar, a forest officer, and a drug farmer.

From this analysis of the evidence it seems clear that no great difficulty need be anticipated in bringing the cultivation of ganja generally under control. There are tracts, no doubt, where measures would have to be taken by degrees and with caution ; but the inclusion of these at the outset in a system of control is not essential.

669. The Commission are further of opinion that control and limitation of cultivation must be accompanied with such supervision of the manufacture and storage of the crop as is necessary to the imposition of a fixed duty on ganja in addition to the fees for licensed vend which are at present levied. In regard to bothAhese matters, the experience of Bengal and the Central Provinces is available, though the systems differ at present as to storage.

670. That there is room for the imposition of a duty on ganja in both presidencies can hardly be doubted. In Madras, though there are several officers of standing who are satisfied with the present arrangement, there is no protest against increasing the duty, while a few witnesses are in favour of increasing the price of the drugs. Mr. Willock, Collector, says : " I am not opposed to an increase of the price of the drug where practicable." Mr, Bradley, Collector, says : " At present I do not think hemp drugs are sufficiently taxed with reference to alcohol." Other advocates of increased taxation are : a District Surgeon, a District Forest Officer, a Deputy Tahsildarrtwo medical practitioners, a jagirdar, a pleader, a merchant, a newspaper editor, bank cashier, and three missionaries. In Bombay there is also a good deal of evidence as to the needlessness of further interference on taxation ; but there is at the same time weighty evidence in favour of increased taxation. Mr. Mackenzie says : " I think the taxation of the hemp drugs in this Presidency might be raised ; but the question would require details and careful examination. The ganja of this Presidency is roughly manufactured, though the cultivation is careful enough. A direct tax would necessitate the adoption of a system of distinct wholesale vend. I see no objections to that, as the tax does not fall on the cultivator. The variations in the retail price shown in paragraph 8 of my memorandum are, no doubt, excessive, and seem to

indicate that there is room for taxation to regulate the wholesale rates of the drug." Mr. Vidal says : " In view of the higher taxation in other provinces, I see no reason why there should not be a higher direct tax in this province. The disproportion between the taxation of liquor and of hemp drugs, and the relative dearness of liquor which results from this, also points to the propriety of increasing taxation on hemp drugs." Mr. Monteath, Collector, says : " I think the present system of excise administration in respect of hemp drugs has worked fairly well, but that the time has come for putting these drugs on the same footing as alcoholic stimulants and opium. Hitherto the consumption of preparations of hemp has not been extensive, and so long as it was very small, the farm of the right to sell, as dispensing with the need of any preventive establishment, was perhaps more suitable. But it seems that not only in this district (Bijapur), but throughout the Presidency, the amounts bid for the right to sell have been increasing, and it may fairly be inferred that the habit of consuming these drugs is spreading. It cannot, indeed, be said yet to be prevalent ; still the total consumption is, I think, sufficient to make it worth while to impose an excise duty ; it is already in this district much in excess of the consumption of opium, though insignificant as compared with the consumption of alcoholic stimulants, particularly toddy. It is, I believe, generally admitted that the system of deriving a revenue by farming the right to sell is suitable only in the earliest stage, and that the levy of an excise duty is the fairest and most satisfactory method of taxing an article produced in the country. Now the levy of an excise duty on preparations of hemp will present no difficulties in this Presidency. The existing abkari establishments would probably suffice for the levy of the duty, or at least would require strengthening to but a small extent. The levy of an excise duty would not, I think, excite any opposition. An alteration in the form of duty could not reasonably be objected to." Mr. Ebden, Collector, says : " The hemp drugs are very much cheaper than liquor now. For a pice a man can get enough ganja to last him for a week if he is a moderate consumer. There is, therefore, considerable margin for heavier taxation of the drug without driving the people to liquor or other intoxicants. I consider there is a considefable margin for taxation, though the drug is consumed by the very poor. I have no sympathy with the excessive consumer, and the moderate consumer would not feel a moderate increase." Mr. Sinclair, Collector, says : " I consider there is a margin for increasing taxation, having regard to the price of other intoxicants, the fact that the drugs are mainly used by the poor, and the danger of smuggling." Mr. Almon, Assistant Collector, Bombay, says: " My impression is that the tax on the drugs is too low. I think that the ordinary liquor consumer pays twice as much for what he wants as the ordinary ganja consumer would, or three times as much as the ordinary bhang drinker. I think the rates should be equalized." Other advocates of increased taxation are three Deputy Collectors, the Administrator of the Jath State, an Assistant to the Commissioner, an inamdar, a mamlatdar, a pleader, and a drug farmer.

671. In view of these opinions, as well as of the general considerations which have been explained above, the Commission have no hesitation in advocating the gradual assimilation of the Madras and Bombay systems to that in force in Bengal. The process of arriving at adequate taxation must necessarily be gradual, but a commencement should be made without any further delay.

The present is the time for this measure, while consumption of ganja is still believed by the authorities to be very limited. It cannot but be the case that the enormous difference between the taxation of liquor and ganja is an incentive to the increase in the drug habit, and such an inconsistency between the arrangements of different provinces and the administration of the excise on different kinds of intoxicants cannot, in their opinion, be any longer maintained.

672. In Berar the foundation has already been laid for the introduction of a system of control in respect of ganja similar to that advocated by the Commission. Cultivation is already restricted and an acreage duty imposed on its growth. The Commission are not aware of the conditions under which this has been found possible. The law of the province stands on a special footing, as previously explained. The Commission believe that there will be no difficulty, and there certainly will be some advantage in assimilating the system to that which exists in the Central Provinces, and which may ultimately be adopted in Bombay. Ganja is inadequately taxed, and it is unlikely that the pitch of taxation necessary to restrict the consumption can be reached otherwise than by a direct duty, or that a much heavier acreage duty will effect the desired object.

673. Not much need be said of the other minor administrations. Progress in Ajmere must depend upon co-operation with the British system in surrounding States. Ultimately it is probable that the system can be assimilated to that in force in the rest of British India. In Coorg the price of ganja is very low owing to the facility of obtaining a supply from the Madras Presidency. When the system of the latter is revised, care should be taken that similar restrictions in Coorg are not wanting. Quetta-Peshin hardly requires special notice. The consumption of ganja must be very small, if it exists at all, as the sources of supply are very distant. The retail price stated to prevail is higher than anywhere else in India except Bengal and Assam.

674. As the only province which receives large imports of charas, the Punjab is primarily concerned with the administration of this drug. Hitherto there has been no taxation of charas in the Punjab beyond the levy of license fees for its vend. It is not used in Assam, Madras, Berar, and Coorg, and but little in Bengal, the Central Provinces, and Bombay. It is used in the Punjab, the North-Western Provinces, Sind, and Quetta-Peshin. Bengal levies a duty of Rs. 8 per ser on the small amount imported, and the Central Provinces Rs. 10 per maund. In Bengal, Mr. Gupta says that it will be necessary ere long to raise the duty. The import duty in Bombay is 8 annas per maund. In the other provinces the only tax is, as in the Punjab, that which is represented by the license fees for vend. Bengal is, therefore, the only province where the taxation is adequate. In the North-Western Provinces it is proposed to levy a duty of Rs. 8o to Rs. Too per maund on all charas imported. In the Punjab, in pursuance of the provisions of Act X of 1893, a duty of Rs. 20 per maund has been proposed. This appears very small. The conditions under which the trade in charas from Yarkand is carried on operate to some extent against more severe taxation. But if provision is made to prevent the tax from being demanded from the actual importers, the Commission are of opinion that there is ample room for taxation without the trade being seriously affected. There is a large amount of responsible evidence for taxing the drug in the Punjab and the North-Western Provinces, where the consumption is far greater than elsewhere, and the Commission think that Rs. 8o per maund is not too high to begin with. Ultimately, regard being had to the consideration above noted, the taxation might be raised considerably.

675. As the supply of charas is so completely within the control of Government, it is not necessary to say much regarding its disposal. The establishment of bonded warehouses, to which the drug can be taken on arrival, and from which it shall be issued only on payment of duty by the licensed vendors, has already been decided upon in the Punjab. This measure will relieve the importers from having to pay the tax in anticipation of sales, and consignments from these warehouses will be sent under pass to the different centres of consumption. The Commission do not think it necessary that the whole duty leviable under provincial arrangement should be demanded when these consignments are removed. The bonded warehouse system may be again resorted to by Local Governments which desire to impose further taxation locally. But as from time to time the Punjab Government will, no doubt, find it possible, with reference to political considerations, to enhance the duty, it will be desirable that there should from the first be an understanding as to the relative claims of the importing province and the consuming province to the duty realized. A similar question has arisen regarding the Rajshahi ganja exported to other provinces, and the procedure has net been uniform. This is one of the cases in which the intervention of the Supreme Government is needed for the settlement of inter-provincial arrangements and of arrangements between British provinces and Native States. It may be necessary to amend the Act in order to carry out the above suggestions. For although section 23-A of the Act provides for the imposition of duty on the imported drug without specifying where it should be paid, section 36 (d) lays down that the bringing of it into British India without payment of the prescribed duty is an offence. The matter is under the c msideration of the Local Government. It is essential that arrangements should be made for taxing charas not at the frontier, but at the bonded warehouses.

676. The difficulty of controlling bhang in Bengal, Assam, the North-Western Provinces, and the Punjab arises from the fact that there is large spontaneous growth in the mountainous and submontane tracts of these provinces. There is undoubtedly a belt of growth which precludes strict control. But in parts of these provinces away from the hills there is little or no spontaneous growth, and in these parts as well as in the other provinces control is possible. There is a little cultivation in the Punjab and the North-Western Provinces, and considerably more in proportion in Sind. None of this cultivation is in the Himalayan region, where the wild growth exists. With the exception of Bengal and the Central Provinces, the only taxation is that realised by auction vend of the monopoly of sale. In Bengal a duty of 8 annas a ser is levied on all bhang brought to the storehouses under Government supervision, which represents but a small fraction of what is illicitly consumed. Without controlling the spontaneous growth of the plant, it has been found impossible to raise the duty, though the subject was fully considered in 1889-90. In the Central Provinces a duty of Rs. 2 per ser is levied on foreign bhang, which operates to prevent the imports from passing a very limited figure. The taxation of this bhang is excessive, and its sale is affected by the fact that only the wholesale dealers are allowed to sell it by retail.

677. The Commission are in favour of taking such measures as are possible for controlling and taxing bhang. For the present they consider that in the belt of growth above referred to nothing more can be done than to auction the monopoly of retail vend. In other parts they are of opinion that cultivation should be prohibited, except under licenses, and arrangements made for the transfer of the whole crop produced from licensed cultivation to the authorised vendors. In these tracts they are of opinion that some attempt may be made to extirpate the spontaneous growth by rendering the occupiers of land responsible that it shall not be found on their lands. Legislation may be necessary for the purpose. They would like to see Mr. Westmacott's circular which was cancelled by the Bengal Government revived, and they would suggest a modification of the Assam circular permitting the use of green or dry hemp for the use of cattle. Now that the habitat of the spontaneous growth has been clearly defined, Local Governments will have no difficulty in deciding where, for the present at least, the existing system must be allowed to continue. The Commission think that it may be impossible to treat the bhang which is produced in ganja-growing tracts in a different manner from ganja. To do so would probably be to imperil the ganja administration. But if this opinion is found to be mistaken, they would be glad to see this bhang more leniently treated than ganja. The Commission find that in the Central Provinces bhang is only permitted to be sold by the wholesale vendors, and the duty is the same as in the case of ganja. The reason for this is not apparent. As judged by the standard of other provinces, the incidence of taxation is high compared to ganja.

678. As regards the distribution of the drugs to retail vendors, the Commission think that when adequate arrangements have been made for their taxation, not much interference is required. The evidence contains various suggestions on this subject. Some witnesses point to the large profits reaped by wholesale vendors, and suggest that these middlemen should be abolished, and that the functions discharged by them should be assumed by the Government in order that these profits may be secured for the public revenues. The Commission are not in favour of this proposal. It is open to some of the objections against a Government monopoly which have been previously stated. If the profits reaped by the wholesale vendors are found to be excessive, this fact would point to a rise in the duty. If the latter is sufficient, the Government need not concern itself with the dealers' profits. Private enterprise is, moreover, better suited for the distribution of the taxed drugs than Government agency. The aim of Government should be to dissociate itself, as far as possible, consistently with efficient control and adequate taxation from the supply of the drugs. This general policy may admit of special exceptions. The Bengal Government has made provision for such exceptions, while affirming the general principle, in the following rule* :—" Except in districts where minimum prices have been prescribed by the Board, no attempt should be made to regulate the price at which spirits, liquor, or drugs are supplied by the producer or wholesale dealer to the retail vendor, or by the retail vendor to the consumer," In the Central Provinces the price at which the wholesale vendor is to supply the drugs to the retail vendor has been fixed for all districts, and the subject has been already considered. This is not done elsewhere in British territory, and any deviation from the above-stated principle seems to the Commission to require special justification. The privilege of wholesale vend should not be too restricted. This will result in great variations of the prices paid by consumers owing to the absence of competition. In Assam the " effect of farming the monopoly of a whole district to a single person has been found to result in very high prices even where smuggling is known to exist," and this should be obviated if possible by freer competition in regard to the supply. If this fails, special arrangements may be required for keeping the price at a reasonable figure.

679. In some provinces import, export, and transport duties are levied ; and this practice is not uncommon in Native States. This practice arises from the want of uniformity which exists in the systems of administration. It 'is attended with considerable difficulties, and serves no useful purpose in itself. If all the drugs were adequately taxed at the sources of supply, subject to such additional taxation as local circumstances demand, the amount of which is best determined by auctioning the licenses for vend, there would be no need for such duties at all. As a supplementary means of taxation, where these requirements are not fulfilled, it may be necessary in special cases to maintain them. This must be the case, at all events for some time to come, if drugs are imported from Native States into British territory. But, if possible, such imports should be entirely prohibited, unless the State concerned has assimilated its system to that in force in British territory. Transport duties from one place to another in British territory should be entirely abolished as soon as adequate taxation of the drugs at the source of supply has been provided for. A system of free passes to licensed persons is all that is needed. Partial measures of this kind tend to obscure the real issue, viz., how far consumption needs to be checked by a rise in duty.

680. The system of retail vend differs largely in the different provinces. In some places the licenses for retail vend of the drugs are held by the same persons and under the same contract as licenses for the sale of opium without any attempt to discriminate the amount of fees due to each. More frequently the licenses cover the sale of all kinds of hemp drugs, and the relative demand for the different kinds is not ascertainable. Where the demand is small there may be reasons for maintaining the latter system, but the hemp drug licenses should, in the opinion of the Commission, be distinct from all others, and in most cases it is desirable that the licenses for the different kinds of hemp drugs should also be distinct ; for it is not the desire of Government that a demand for any of the drugs should be created. Shop licenses should only be given where the demand exists, and there may be a demand for one kind and not for another. The demand for a bhang license, for instance, should not be responded to by licensing the sale of ganja or charas in addition, which may not be necessary. As a rule the licenses should be sold separately. As Mr. Stoker says : " This would enable us to provide for the sale of the more harmless forms of the drugs without the others, and to meet the demand for one form without allowing the sale of the other forms of the drug. "

681. As to the question whether the licenses for different shops should be sold separately or collectively for any given tract, the Commission are not prepared to generalize. The latter system affords a better guarantee for the respectability of the licensee, and has the merit of simplicity. But where auction bids are affected by combinations, the separate system may be desirable. The matter is one that must be left to the discretion of Local Governments and Administrations.

682. The Commission are averse, as a rule, to the grant of retail licenses to wholesale vendors, and there is a good deal of evidence against the practice. It is not desirable to insist on the wholesale vendors becoming also the retail vendors, and diversity of practice tends to produce complications. If both functions reside in the same person, he has too extensive a monopoly, and will command the market to an undesirable extent. It cannot be too strongly insisted upon that uniformity and simplicity of system are essential to providing the means for ascertaining whether the drugs are sufficiently taxed ; and when some of the shops are held by the wholesale vendors, and others by separate retail vendors, it is more difficult to gauge accurately the effect of the system. At the same time the Commission are aware that the practice of allowing wholesale vendors to hold retail licenses is very general, and they are unable to recommend that it should be authoritatively put a stop to. The subject is one which they would commend to the notice of Local Governments with reference to the above remarks.

683. A separate license should be granted for each shop. This is ordinarily the practice, but there are exceptions. None should be permitted. The District Officer should watch the auction bids and refuse to renew licenses if they only amount to a nominal figure. The principle should be to supply a real demand, not to create one; and if the demand only exists to a very limited extent, the danger of stimulating it must prevail against the convenience of the very limited number of consumers. The number of the population per retail license in the different provinces in 1892-93 was as follows :—

|

Bengal |

23,560 |

|

Assam |

19,975 |

|

North-Western Provinces |

12,012 |

|

Punjab |

12,869 |

|

Central Provinces |

9,109 |

|

Madras |

144,781. |

|

Bombay |

43,528 |

|

Sind |

4,478 |

|

Berar |

6,061 |

|

Ajmere |

30,130 |

|

Coorg |

28,842 |

The number of shops in 'Madras is only 246, and the allegation of some of the witnesses that there is no need for shops because the consumers of ganja can get ganja when they require it from the cultivators receives confirmation from these statistics. In Bombay the number of shops is stated to be nearly double the number of retail licenses, and the difference is not explained. The number of souls per shop is only 24,681. No doubt density of population is an element in the consideration, and thinly populated tracts will require more shops proportionally than where population is dense ; but the number of shops in the North-West-em Provinces, Punjab, Central Provinces, Sind, and Berar seem to require attention with reference to these remarks. A considerable reduction of shops has been under consideration in the North-Western Provinces which was to come into force in 1893-94.