| - |

Drug Abuse

CHAPTER VIII. EXTENT OF USE AND THE MANNER AND FORMS IN WHICH THE HEMP DRUGS ARE CONSUMED.

335 In endeavouring to measure the extent to which the hemp drugs are used, it will be best to deal with them in their simplest forms of ganja, bhang, and charas. The excise administration of the hemp drugs in Bengal is so systematic that the statistics of registered sale to retail vendors may be accepted as correct ; and with regard to ganja and charas, they will be found to afford a very good indication of the actual consumption. With bhang the case is different, for most of this drug which is consumed outside the big cities escapes excise altogether. And the cities in which it can with any approach to truth be said that unexcised bhang is not consumed are very few.

Ganja is the most important of the three drugs ; it contributes nearly the whole of the hemp drug revenue, and is consumed in all parts of the province. In the case of Bengal it is possible to form with the help of the statistics a fairly accurate idea of the extent to which the use of it prevails in the various divisions and districts. On this subject a statement appears in the Excise Report for 1892-93: " Its consumption is largest in Calcutta, and next in Mymensingh and Dacca ; it is also considerable in the 24-Parganas, Rangpur, Pabna, Tippera, Cuttack, Puri, and the districts of Behar" ; and the qualification is added that the large apparent consumption in Behar is to be explained to some extent by export to the North-Western Provinces.

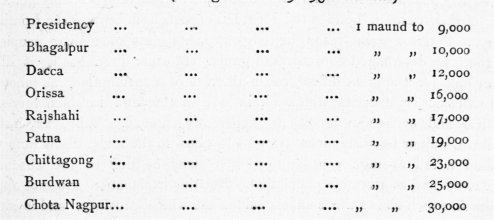

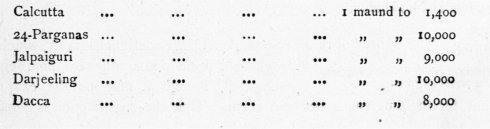

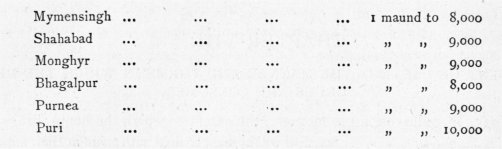

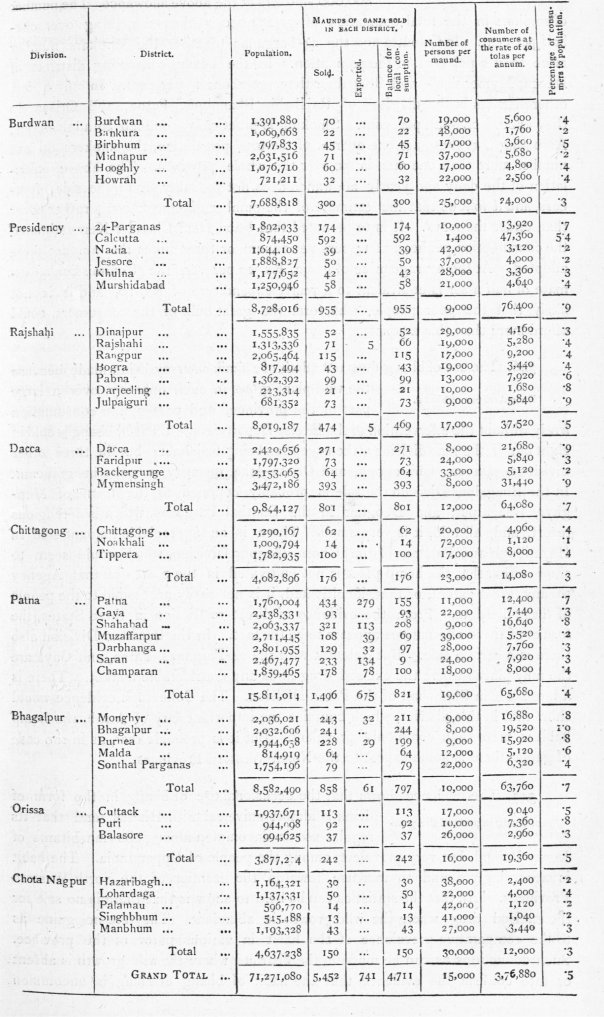

336. If the quantity sold in each division and district be compared with their population, it will be found that the divisions rank as follows (the figures of 1892-93 are taken)—

and that the districts in which one maund does not suffice, or barely suffices, for 10,000 of the population are :—

337. The circumstances of Calcutta are of course altogether abnormal. It contains a vast number of coolies and day labourers, and workers in boats and on the river-side, besides a large foreign population, many of whom, such as domestic servants, porters, and watchmen attached to Government offices, to houses of business, and to private persons, and the followers of wealthy people, are notoriously addicted to the hemp drugs in one form or other. There are also present in the city all the conditions which tend to luxury and excess. The evidence shows that the use of ganja by some of the well-to-do classes is by no means rare, and the probability is that with people who have acquired the taste and can afford to gratify it freely the indulgence is not stinted either to themselves or their friends. Calcutta, therefore, not only contains amongst its population an unusually high proportion of consumers, but the consumers also take considerably more than the average individual allowance.

338. The districts where the consumption is highest come far behind the city of Calcutta. The favour in which the drug is held in the 24-Parganas is probably due in great measure to the neighbourhood of Calcutta ; but it is also in evidence that the inhabitants of low and swampy tracts and the river population are specially addicted to it. Similar reasons, Dacca being a large city, may account for the high consumption of the districts of Dacca and Mymensingh. The shops in Darjeeling, Jalpaiguri, Shahabad, Monghyr, Bhagalpur, and Purnea very probably get a good deal of their custom, besides the recorded export, from beyond the frontiers of Bengal. Puri is a great resort of religious mendicants and similar people who are the most determined consumers of ganja. In other directions it • is difficult to account for the great difference in the rate of consumption, as shown by the retail sales, in districts which adjoin one another, and in which very similar physical and economic conditions apparently prevail. Why, for instance, should Dinajpur be abstemious, lying as it does in the midst of districts which all show a full average consumption ? It may be due to the absence of large rivers and of riverside population. But this explanation will not apply to Noakhali, which shows the smallest sale in the whole province, and is situated between Tippera and Chittagong, the former of which the Excise Commissioner regards as a district of heavy consumption, and the latter being not very exceptional in this respect. The consumption of opium and liquor is also very low in Noakhali.

339. The figures of retail sale mark off large continuous tracts, which can be distinguished from one another by their degrees of consumption, though it may not be easy to account for the differences between them. Thus the consumption is consistently low throughout the four hill districts of the Chota Nagpur Division, the comparatively high rate of Lohardaga being due in all probability to the fact that Ranchi, the head-quarters of the division, has a considerable population of foreigners. Manbhum in the Chota Nagpur Division, Bankura and Midnapur in the Burdwan Division, and Balasore in Orissa form the skirt of the southwestern hill tract, and are content with one maund of ganja for every 2,-,ocio of the population. There is probably a certain amount of smuggling from the Hill States into these districts, but it can hardly be sufficient to affect their character as ganja consumers in the comparison now being made. Northeast and east of Calcutta lies a huge tract of low consumption, comprising the districts of Noakhali, Khulna, Jessore, Nadia, Backergunge, and Faridpur. This fact hardly bears out the theory that residence in low-lying country and river-side life are very intimately connected with the ganja habit. In the districts situated immediately west and north-west of Calcutta, and in the Rajshahi Division and in Malda, the consumption is about average. Further west, in the Patna Division, the consumption falls off.

340. The province might possibly be divided into two portions so as to indicate consumption above and below the average. A straight line drawn from Monghyr on the Ganges to Raipura on the Megna in the Noakhali district, and turned north and east at the respective ends direct to the frontiers of the province, would mark off broadly the portion in which consumption exceeds one maund to 15,000 of the population. It would include all the river population on the Ganges and Brahmaputra between the two places named. South and .west of this line there would be found only Calcutta, the 24-Parganas, and Puri with consumption exceeding the above figure.

341. The consumption of the whole province, including Calcutta, is one maund to 13,000 of the population, and excluding Calcutta one maund to 14,00o. This maund consists of the drug as issued from the local golas, while the figures of consumption given by witnesses represent the quantity of the detached pieces of ganja as they are manipulated for use. Allowing for the waste between the gola and the chillunz, it will be fair to put the consumption at one maund to 16,000 of the population.

342. The Excise Commissioner reports that the average retail price of ganja is Rs. 20 per ser. It ranges from Rs. 12 in Calcutta, Patna, Cuttack, and Chittagong to above Rs. 30 in Mymensingh, or from 21 annas to more than 6 annas per tola, the average being 4 annas. It appears from the evidence that i16th of a tola is the smallest quantity that will suffice for one chillunz, and that more is required if more than two or three smokers have to partake of it. That quantity apparently affords one smoke to two persons, and the refreshment seems to be generally taken twice a day. For the most moderate habitual smokers, therefore, -11th of a tola may be taken as the daily allowance. This represents an expenditure of 4 anna a day and a yearly allowance of 23 tolas. But Mr. Gupta reports, and he is corroborated by the great bulk of the witnesses, that the average allowance is higher than this, lying between 4 anna and e anna per diem. Accepting this opinion, the daily cost to the moderate consumer may be put at 41 pies, and the

yearly allowance at 35 tolas. In order to frame an estimate of the total number of consumers who are supplied by the yearly sale of excised ganja, the excess allowance of excessive consumers has to be added to this figure.

343 The following very clear statement on the subject of moderate and excessive consumption may be quoted from the evidence of Babu Gobind Chandra Das, Deputy Magistrate and Collector of Malda

" I have taken some statistics on this point. The ganja shop at this town of English-bazar sells ganja at the rate of Rs. 20 a ser. I enquired of a large number of persons who come to purchase ganja at this shop as to their daily consumption of their drug. Altogether 378 persons were examined. Of these, 247 persons stated that they spent a pice (¼ anna) a day on this drug, I06 persons gave 2 pice (½ anna) as their daily expenditure on ganja, whilst only 13, 7, 1, 3, and t stated their daily consumption to be 3 (I anna), 4 (x anna), 5 (2 annas), 8 (2 annas), and to (2 annas) pice respectively. I am sure most of these men understated their consumption to a very considerable extent. But looking to the fact that purchasers of ganja are not the only persons who consume the drug, and that a large number of persons who consume ganja do so at the expense of their richer companions, I think it is safe to say that the majority of ganja smokers do not spend more than two pice (I anna) a day upon ganja. The retail price of ganja in this district is about Rs. 2o, so that two pice anna) can fetch a man only 8th tola of ganja. This is not sufficient for more than three chillums. I think it cannot be considered as excessive. On this datum it can be said that the majority of the ganja smokers are moderate consumers. As regards occasional consumers, all that can be said is that their number is extremely small. In fact, it is impossible for a man to consume even a pretty large quantity unless he is a habitual consumer and has kept up the habit by daily use."

This estimate of daily moderate consumption is rather higher than has been adopted above on consideration of all the available evidence ; but the witness's general conclusions appear to be sound. The extremely small proportion of excessive consumers is corroborated by many witnesses who have devoted care and thought to the question, though it falls below the estimate of the bulk of those who have contented themselves with simply putting down their opinions in figures without discussion or comment. The witness quoted does not make special mention in this place of the religious classes. He states elsewhere (answer 20) that the number of a special class of them in his district is about in 1 op souls, which is not a small proportion. The addition of the other classes of religious ascetics and mendicants will give a considerably higher ratio, and the district will then have a full average proportion of these people. They have probably therefore entered into the enquiries and calculations of the witness which may be accepted as fairly representative of all classes of consumers, including that which is notorious for excessive use of the hemp drugs.

344. The excessive consumers then must be regarded as bearing but a small proportion to the moderate—certainly not more than 5 per cent , or 1 to 20. And this accords with reason, for the bulk of the consumers of ganja are poor and cannot afford over-indulgence in a luxury which, in Bengal at all events, is not cheap. The yearly consumption of a moderate individual has been estimated at 35 tolas, and distributing the excess amount taken by immoderate users over the whole number of consumers, the individual allowance for a year may be put at 40 tolas, which is half a ser or one-eightieth of a maund. By this measure the number of consumers of excised ganja is easily calculated, and is shown in the attached statement.

345. A fair average consumption for the whole province, exclusive of the Native States, is 5,000 maunds, and this suffices for 400,000 smokers at the above allowance. The number of smokers in the total. population of 71,271,000 is thus something over one-half per cent. In Calcutta and the 24-Parganas together the smokers number more than 2 per cent. of the population. In the heavy consuming districts of Dacca, Mymensingh, and Bhagalpur they are about I per cent. In only a few other districts in the divisions of Rajshahi, Bhagalpur, Patna, and Orissa do they exceed one-half per cent. Smoking is practically confined to adult males. Assuming that these are one-quarter of the total population, the smokers do not number more than one man in so over the whole province. The above calculation of the daily and yearly allowance does not probably err on the side of excess, and it follows that the estimate of the number of consumers is rather over than under the mark. It is to be noted that Babu Hem Chunder Kerr estimated the consumption per head at 1 2 stirs per annum, or three times the amount here adopted. At the average price of ganja, Rs. 20 per ser, the Commission's estimate of half a ser is equivalent to a yearly expenditure of Rs. io, and it is not likely that the poor people, who form the great bulk of the consumers, could afford more than this amount.

346. The use of bhang does not admit of a similar survey being made, because the wild plant grows in such quantity over a large part of the province, and passes into consumption freely without the intervention of the Excise Department. Excised bhang is sold in eight out of the nine divisions, the exception being Rajshahi ; but in three other divisions—Dacca, Chittagong, and Orissa—the quantity is quite insignificant. In the Bhagalpur Division the sale is probably confined to the towns of Monghyr, Bhagalpur, and Deoghur in the Sonthal Parganas, which is a religious resort, and, all told, it is very small. There is an appreciable amount sold in Hazaribagh and Palamau of the Chota Nagpur Division, which would seem to show either that the hemp plant is not cultivated in the States of that Agency to any great extent, or that, if cultivated, it is not easily accessible to the people of these districts. From the evidence of direct restriction in these States, the former of these alternatives appears to be the fact. In the Burdwan Division also there is a certain sale. But Calcutta with the 24-Parganas, Patna, and Gaya are the only places where the excised drug finds any considerable market. There is a large sale in Shahabad of the Patna Division. The Collector's evidence would show that in this district, which contains the important city of Arrah, the hemp habit is more than commonly prevalent. But it is probable that, as in the case of ganja, there is some export to the North-Western Provinces.

347. The evidence shows that the occasional use of bhang in the form of drink is almost universal with Hindus, and that its regular use is uncommon among the inhabitants of Lower Bengal, but very prevalent among the people of Upper India. The habit is accordingly found to increase towards the frontier of the North-Western Provinces. All that the statistics can be held to show is that there is no sale for the excised drug where the wild growth is abundant. They are no guide as to the comparative prevalence of the habit in various parts of the province. Such deductions as can be made in the districts where the wild growth is absent or rare confirm the evidence that the habit of bhang drinking is uncommon with the Bengalis. Under these circumstances it is not worth while, even in these districts, to attempt to measure the prevalence of the habit with more exactness.

348. But the evidence throws some light on the amount of individual consumption, and the statistics of Calcutta may prove interesting. The average total consumption of bhang in Calcutta during the last 5 years has been 440 maunds, which is about one maund to 2,000 of the population, or somewhat less than the rate of ganja consumption measure for measure. The retail price of the drug is about Rs. 21 or Rs. 3 per ser (memo. and witness 123). The daily allowance is very irregular. It is stated by Babu Hem Chunder Kerr that moderate use ranges from I-- tola to 2 tolas a day, and by others that t tola is the usual allowance, and that even this small amount is sometimes made to last for two or three days. The explanation of this irregularity is probably to be found in the facts that the drug is cheap, that it is not very potent, and large doses do not therefore produce unpleasant consequences ; that the preparation of the drink is somewhat troublesome and inconvenient ; and that the intermittent and occasional use as a cooling draught is common.

A yearly allowance of 21 sers represents a daily use of little over ½ a tola in quantity and 4 anna in price—figures which appear reasonable and in accordance with the evidence. At this rate the yearly sale of Calcutta would supply about 7,000 persons. There are many consumers, especially up-country people, who take more than the allowance on which this calculation is based. But, on the other hand, the above number must be multiplied by a high figure if it is sought to include all who take the drug occasionally.

349. Charas is an expensive luxury, and its use in Bengal is very limited. The total consumption in the city of Calcutta and the district of Murshidabad is only II maunds. The Excise Commissioner reports that the average price of charas is Rs. 4o a ser, or double that of ganja. The dose seems to be about the same as that of ganja in each smoke. But the drug is used by people of better means. It is therefore in all probability taken more liberally, and excess is more common. The individual cost would therefore come to far more than double the cost of ganja. The daily allowance might be put at I tola, costing 2 annas. The yearly consumption would thus be about one ser per head of the consumers, and the total import of I I maunds 26 sers would suffice for 466 persons. It may be noted that in Bengal charas is reputed to be weaker than ganja. It is possible that this may be true as the result of deterioration of the former in coming from the Punjab.

350. The figures relating to ganja consumed in the province for the last 20 years, as shown by the sales to retail vendors in the various districts, show a large decrease from the first period of 5 years. The figures are as follows :-

Average Maunds.

1873-78 ••• ••• 7,111

1878-83 ••• ••• 5,297

1883-88 ••• ••• 5,249

1888-93 ••• ••• 5,133

The proportions of the various kinds of ganja have varied considerably during these periods, but, after having attempted to estimate the effect of these variations, the Commission find that the general result is the same as that above-shown, viz., that consumption has been stationary during the last 15 years, but that the average consumption has been much less than that of the previous 5 years. The increase of population, however, during this period must not be lost sight of. It amounted to about 71- per cent. between 1881 and 1891, and, notwithstanding this, there was no increase in consumption during this period. In districts where the consumption has decreased, there are witnesses who say that the enhanced cost of ganja has reduced, and is reducing, the habit. Evidence is not wanting, however, to show that other causes also may have been at work to produce the result. The growing taste for liquor is one of the principal causes mentioned. This refers to the superior classes. One deposition alone (Patna District Board, 248) states that the low price of country liquor has caused a decrease in the sale of ganja among the inferior classes. This evidence, however, is contrary to the view held by the Excise Commissioner, who states in hi§ memorandum (paragraph 651 that liquor, even in Bihar, is much dearer than ganja. Babu Hem Chunder Kerr attributes decrease to the disrepute in which the habit is held and the belief that its effects are baneful. An Utopian zamindar, a Muhammadan, attributes the decrease to the enlargement of the peoples' minds by education, the action of temperance associations, the publication of treatises and tracts which condemn the drugs, and the spread of civilization. In the statements of witnesses who endeavour to explain the increase alleged to have occurred in their own particular districts, the following reasons for such increase are given. In exact contradiction to the evidence that the growing taste for liquor is reducing the consumption of ganja among the better classes, it is now occasionally stated that the great cost of the liquor habit and its deleterious effects are making the same classes go back to ganja. Among the lower classes the raising of the price of liquor under the central distillery system is also said to be a direct encouragement to ganja. It is even stated that the example of the better classes is an encouragement to the lower, although the weight of evidence tends to show that the former are abandoning ganja. The better wages earned by the labouring classes, who are the principal consumers of ganja, is sometimes held to account for the increase. Bad seasons and oonsequent want of means have, it is said, brought the cheapest intoxicant into favour. As a special cause is mentioned the recent establishment of a new form of worship of Trinath in Eastern Bengal. The existence of the shops is said to be a direct incentive to consumption, but the statement of witness (202) that the officers of Government make strenuous efforts to push the sale, presumably for the sake of the revenue, was not sustained under oral examination. Some of the above reasons apply also to the increased consumption of bhang, which is far cheaper than ganja. And another very good reason is given in respect to this form of the drug, viz., the influx of up-country workers into the mills and similar industries of Calcutta and its neighbourhood.

351. The above analysis of the evidence gives some of the reasons alleged by individual witnesses for local increase or decrease, and indicates the various causes which have assisted or interfered with the general tendency to decrease which is manifested in the provincial statistics as a whole.

352. The statistics furnished by the Kuch Behar State show an average retail sale of 76 maunds, which by the standard of the province should supply 6,000 consumers, or more than 1 per cent. of the population. The consumption seems to be stationary, though there is a gradual decrease of retail sale in the last three years.

353 There are no means whatever of judging of the extent of use in these States.

354 In the North-Western Provinces all three drugs—ganja, charas, and bhang—are very largely consumed. Bhang is used everywhere, and there is no evidence to show that the use is more common in one part of the province than another, if the Kumaon Division be excepted. It would appear that in the mountains the drug is only drunk or eaten in the form of majum by a few well-to-do people in the towns at the Holi festival. But the consumption is heavy in particular spots, such as Mathra, the home of the Chaubes, who appear to be the greatest and most notorious bhang drinkers in the whole of India, and Benares and other holy places on the Ganges. With regard to ganja and charas, the province may be divided into three parts. In the western portion, consisting of the divisions of Meerut, Rohilkhand, and Kumaon, ganja is hardly used at all. The statistics show no imports except at Shahjahanpur, which is on the extreme east of this section of the province. The drug in favour here is charas to the exclusion of ganja. In the eastern and southern portion. comprising the divisions of Benares, Gorakhpur, Allahabad, and great part of Fyzabad, ganja holds the field, though not to the exclusion of charas, except in the districts bordering on Bundelkhand. In the central portion of the province, comprising the Agra and Lucknow Divisions and part of the Allahabad and Fyzabad Divisions, both drugs seem to be freely consumed.

355. In dealing with the trade of the province, the figure of imports of ganja given in the statistics was accepted in full view of Mr. Stoker's caution that it was not reliable, and his estimate that the import was between 4,00o and 4,500 maunds. For the present purpose the same figure, though in excess of Mr. Stoker's figure, may be taken ; for it is necessary to include the local unexcised ganja, which no doubt comes into use in some quantity. In Bengal but small allowance was made for waste, and since figures of sale to retail vendors were supplied, only the waste which took place between the local gola and the chillum had to be considered. In dealing with the drug in the state in which it is imported, and with an import the greater part of which consists of an article which is less carefully prepared and far less valuable than Bengal ganja, a much higher allowance for waste must be made. Taking all things into consideration, it is doubtful if the consumption can be fairly fixed at more than 3,500 maunds. The North-Western Provinces give no figures of retail sale to aid this calculation. The total population of the province is 47,000,000, and one maund of ganja therefore suffices for some 13,000 persons. If the population of the divisions of Meerut, Rohilkhand, and Kumaon, where ganja is not used, be deducted (about 12,000,000), the maund

of ganja suffices for only 10,000 persons. Judged by the Bengal standard, this is a high figure; but the cheapness and comparative weakness of the greater North-Western Provinces. part of the drug consumed in the North-Western Provinces may well induce a liberal use, and this result may approximate to the truth.

356. Mr. Stoker does not accept Babu Hem Chunder Kerr's estimate of average consumption per head at the high figure of 1½ sers. At 6 annas a tola this means Rs. 45 a year, and this is obviously quite beyond the means of the consumers of average means. The individual consumption in Bengal has been estimated at half a ser, or Rs. to per annum. Mr. Stoker, dealing with a drug or mixed drug that costs less than baluchar, calculates the individual consumption at one ser, and the whole supply of 4,500 maunds as sufficient for 18o,000 smokers. By the Bengal standard 3,500 maunds would supply 280,000 persons. It seems proper to make allowance for the cheapness of the drug and adopt the mean of the above calculations, or 230,000. This represents something less than per cent. of the population. In the cities, baluchar sells at 6 annas a tola. It is cheaper in the villages probably because it is adulterated with pathar, which is anything from one-twelfth to one-sixth of the price of the other. If the average annual allowance of something less than one ser be regarded as being composed of f baluchar and 4 pathar, the cost comes to a reasonable figure.

357. With regard to charas, Mr. Stoker estimates the individual consumption at half a ser per annum. For Calcutta it was put as high as one ser, because it was regarded as a luxury of the comparatively wealthy. But it does not hold that position in the North-Western Provinces. The evidence shows that it is used by the poor more than by the rich. In many places it is actually cheaper than baluchar ganja, and being stronger less of it is used at a time. It is probable that Mr. Stoker's estimate approximates to the truth, and that the 1,15o maunds imported are consumed by about 92,000 persons. The use is most common in the Meerut, Rohilkhand, and Kumaon Divisions, and decreases towards the east of the province ; but it is found in all districts, except those bordering on Bundelkhand, where the consumption is trifling. The consumers are at the above figure about one-fifth per cent. of the population, and this covers an addition for the small indigenous production of Kumaon.

358. Bhang is not used regularly like charas and ganja. There is reason to think that a large number of the better class of Hindus take it in extremely hot weather, and that it is a regular refreshment with a very large proportion of them in the summer. There are no statistics of consumption ; the drug can often be had for almost nothing from the abundant wild growth, and is always very cheap. The price of bhang seems to range from 4 annas to as much as one rupee a ser in towns, tats bhang from Farakhabad being more expensive than commoner kinds, while baluchar ganja is Rs. 20 to Rs. 30, charas Rs. 71 to Rs. 25, Nepal ganja going as high as Rs. 35 and Rs. 4o a ser, and pathar ganja Rs. 21 to Rs. 5.

359 In the last twenty years, from 1873 to 1892, the hemp drug revenue of the North-Western Provinces and Oudh has grown from 4 to 7 lakhs. The increase in Oudh has been 193 per cent., and in the North-Western Provinces 5o per cent. It is from the figures of revenue, in the absence of statistics of retail sale, that deductions have to be made as to the rise or fall of the consumption of the drugs.

360. Mr. Stoker connects these fluctuations in some important instances with changes in the administration of the liquor excise. He shows pretty conclusively that the hemp drug revenue has risen when the price of liquor has been raised, and that it has fallen when under the establishment of the outstill instead of the central distillery system liquor has been made more plentiful and more cheap. It is stated that the liquor revenue has in the same period grown from 17 to 32 lakhs, and that the enhanced revenue has been raised on a diminished issue of liquor. If there is this intimate relation between liquor and the hemp drugs, it seems to follow that the decreased consumption of liquor must have been accompanied by an increased consumption of the hemp drugs. And to this a reasonable addition must be made on account of an increase of 5 millions in the population in the twenty years' period. There is no reason to doubt that increase of consumption assignable to these two causes has actually occurred, for they are to all intents and purposes independent of any check or restriction arising out of the present system of hemp drug excise. The evidence shows that bhang has not got dearer ; that the enhanced cost of baluchar, due to the Bengal duty, has been counteracted by the supply of a cheaper article ; and that charas has actually been falling in price, thanks to improved communications.

361. Besides indicating the relationship between the liquor and the hemp drug habits, the figures of revenue, great though expansion has been, do not go far to assist in ascertaining whether the consumption of the hemp drugs has grown or not. There is the probability that the demand has increased, bringing greater profits and consequently more keen competition amongst the purchasers of the farms. But Mr. Stoker's remarks lead to the belief that the enhancement of the revenue has been due partly to improved management, resulting in the checking of clandestine practices, or, as he describes it, the stopping of " leakage. " To judge by the instances given, losses of this sort were very considerable ; and this reform, together with the prevention of smuggling and illicit traffic, would go far to account for the increase.

362. Turning to the evidence, there is little definite testimony of increased consumption, in which it is clear that the opinion is based on actual observation. There are not in this province as there are in Bengal definite statistics on which to form an opinion as to increase or decrease. The preponderance of testimony is in favour of increasing consumption, and the high price of liquor is more frequently alleged as the cause than anything else. Witness (20) makes a very definite statement on this point. Allied to the reason connected with liquor is found the closing of chandu and madak shops mentioned by some witnesses. Other causes given are the accessibility and cheapness of the drugs, the weakening of social and religious restraints, facilities for travelling leading to the circulation of bad habits, general demoralization, and the increase of poverty and the number of sadhus and mendicants. It is stated by some witnesses that under Moghal rule the drugs were prohibited and their consumption suppressed by penalties such as whipping and mutilation, and that the present liberty has degenerated into license. On the other hand, the perversity which drives people to do what is restricted or prohibited'is -alleged by another as the cause of increase. Another attributes increase to experience of the beneficial effects of use of the drugs. It appears that there is an organized movement among the Kayasths which forbids the drinking of liquor, and that these people are taking to bhang instead. Some witnesses allege that irrigation in rendering the country damp and cold makes the drugs a necessity, and one that the use of charas is increasing because the drug " is generally prepared and sold (as retail dealing) by the fair sex in large towns." This last matter was taken up by the Commission, and will be noticed further on.

363. But the evidence is not all on the side of increase. Some witnesses think that the consumption is stationary, and some that it is decreasing. The principal cause of decrease alleged is the change of habit among the higher classes and the better-to-do of the lower in the direction of liquor. The high cost of the drugs has, according to one or two witnesses, caused people to abandon them.

364. There is some evidence that ganja is being supplanted by charas in public favour. Mr. Wall, late Commissioner of Excise wrote as far back as 1881 : " From the large proportion which charas bears to other drugs in large cities like Allahabad and Ben_ares, and from the increase in license fees for sale of charas which is noticed by the Bengal Government, it is highly probable that charas is coming into favour. It is, in fact, said that within the last few years, owing to increased duty levied on baluchar ganja in Lower Bengal, the consumption of charas has largely increased everywhere." Charas is now even cheaper as compared with Bengal ganja than it was then, and there is some evidence that the change is still going on.

365. The Revenue Member of the Rampur Council of Regency (35) states that people smoke ganja and charas everywhere in the North-Western Provinces and in the State of Rampur. Rampur, however, is situated in the Rohilkhand Division, where charas appears to be used almost exclusively. It is probable, therefore, that the statement about the use of ganja in Rampur is rather too general. This witness also alleges that the use of all three drugs is increasing because they are cheap, and they are not forbidden by the Hindu religion.

366. The use of the drugs in Tehri Garhwal is probably as prevalent as it is in Kumaon and British Garhwal. There is no special information for the State, but from the evidence of witness (49) it may be assumed that charas is the only form of the drug used ; that its use is not extensive, but possibly spreading through " a growing tendency to take narcotics of all kinds."

367. In the Punjab the use of ganja disappears, the indications of its existence being found only in the statements of occasional witnesses. It has no place in the excise arrangements. Charas and bhang are used to a greater or less extent in all parts of the province. Regarding bhang, the Excise Commissioner admits that a certain quantity is consumed without passing through the hands of the licensed vendors, but he does not think that it is very great, because the people of the parts in which the plant grows wild are not addicted to its use, while the retail price (three or four annas a ser) is so small that it is not worth while for a consumer to attempt to obtain a supply elsewhere than from the nearest licensed shop. There is, however, reason to believe that in the south-west corner of the province, where the use of bhang is most prevalent and cultivation is carried on to the extent of about too acres, a considerable share of the locally grown drug escapes excise. Regarding charas also, it is probable that the figures of retail sale do not represent the full consumption. These considerations do not, however, affect the view of comparative consumption of the two drugs over the province which the Excise Commissioner has presented in his memorandum, except possibly that the consumption of bhang in the south-east corner may be larger than is represented.

368. Taking charas first, it will be seen that its use is most prevalent in the Ludhiana district, and to a somewhat less degree in the Himalayan districts, and in and about the cities of Delhi, Umballa, Amritsar, Lahore, and Peshawar, and that generally the eastern half of the province has decidedly more inclination to the drug than the western half. The measure by which the two halves of the province are differentiated is a consumption of 5 ounces by too of population. This measure might be raised to 6 ounces on account of defective registration of sale, and expressed in the terms used for Bengal in this report as one maund to 2 I,5oo of the population. The rate of consumption in Ludhiana is double of this, or one maund in topoo, and in the greater part of the western half of the province is hardly more than one maund to 60,000.

369. In the North-Western Provinces Mr. Stoker estimated the individual consumption of charas at half a ser per annum. In the Punjab a somewhat higher rate might be adopted because the drug is cheaper, the price to consumers ranging from Rs. 4 to Rs.15 per ser in this province, while in the North-Western Provinces it was Rs. 71 to Rs, 25. If the number of consumers be taken at 6o instead of 8o to the maund, the total number for a total consumption of 1,200 maunds will be 72,000. The divisions of Delhi, Jullundur, and Lahore consume five times as much as Rawalpindi, Peshawar, and the Derajat, and there must therefore be 6o,000 consumers in the former to 12,000 in the latter. In this comparison also the province falls into the same halves as before, for the consumption of the districts of Montgomery, Multan, and Jhang in the Lahore Division barely reaches 20 maunds, and does not therefore materially affect the figures.

370. The total retail sale of bhang on the average of the last five years is 3,800 maunds. This probably falls considerably short of the actual consumption owing to the existence of the wild growth in many districts, the regular cultivation which is carried on in the south-western districts, and the homestead cultivation which seems to prevail all over the province to a limited extent. A very appreciable supply must be got direct from these three sources without the intervention of the licensed vendors. Maunds 4,200 would represent a supply of one maund to every 5,000 of the population. The Excise Commissioner finds that the south-eastern districts have the heaviest consumption, too to 145 oz. to too of the population, or about one maund to t,000 persons ; the central districts come next with about one maund to 4,000 of the population, and the rest of the province consumes one maund to about 8,000, except that the districts of Delhi and Ludhiana almost come up to the districts of heaviest consumption.

371. Bhang is so cheap, 3 or 4 annas a ser, as to give very wide latitude for individual indulgence. On the other hand, a great share of the consumers, perhaps the majority, are above the class of the very poor, and the drug is to a great extent used with ingredients which are more or less expensive. Occasional use, either regulated by the season, or prompted by the weather, or connected with social and religious observances, is also very common. These things make it extremely difficult to state any estimate of the number of consumers, though a figure of total consumption has been arrived at. It is very doubtful if more than about half of the total consumption, or 2,000 maunds, is taken by regular and habitual consumers. For such persons, at the price given above, two tolas a day, or ten sers in the year, would not be an extravagant allowance. The cost of this would be less than three rupees a year, and the ingredients would bring the expenditure up to about Rs. 10. The number of habitual consumers would thus be about 8,000. This estimate of individual consumption accords with the evidence on the particular point. The occasional consumers are many times more numerous. The description which is to follow of the " classes of consumers " and of the " social and religious customs" connected with the use of the drugs will throw more light on the extent of the occasional use of bhang. The use as a summer drink seems to be much more common in the northern parts of India, which are characterized by intense dry heat, than in the southern. The dividing line might be drawn with fair accuracy from the Runn of Cutch to Darjeeling.

372. The statistical table in the form prescribed by the Commission gives retail sales from the year 1875-76 to 1892-93. But in the first five of these years it is obvious that the figures include transactions other than retail sale in column 45. From 1881-82 onwards there is a steady increase in the figure for charas, interrupted only by a fall in the year 1890-91, which, however, was more than made up by the rise of the following year. In the year 1892-93 the figure is 6 maunds less than in 1891-92. As regards bhang, the figures of the whole period 188o-81 to 1892-93 do not offer any definite suggestion of increase or decrease. Their regularity might, however, tend to remove the hesitation which the Commission feel in accepting the figures for charas as a reliable index of consumption if it were not that bhang is so cheap that there can be little temptation either to smuggling outside the shops or the keeping of incorrect accounts within them. The sale of other preparations of hemp shows a steady decrease. These preparations must include majum and other sweetmeats into which hemp enters. They are not very important, and it is not therefore worth while to speculate whether the decrease of sale means a real decrease of consumption or not. It would be necessary to proceed on mere conjecture, for the evidence and Government papers throw no light on the subject.

373. Regarding rise or fall in the consumption of bhang also, there is little to be said. Mr. Diummond states that the use of this form of the drug is increasing in the southeastern districts, and that caste movements against alcohol, enhanced cost of spirits, and growing prosperity among the Jats may account for it. But there is little other evidence to indicate increase, and the statistics of the Delhi Division do not suggest it. On the contrary, there is evidence that the better classes are giving up bhang for liquor—a change of habit which has been noticed in other provinces.

374. The steady and considerable increase which the statistics of the consumption of charas shew in the last ten years is not reflected in the evidence in a very decided manner. It is true there are some who allege increase as being caused by the development of the Central Asian trade, the fall in the price of charas, the increase in the number of shops, the increase of population, and the addition to the number of poor and idle people. But there are many who allege decrease ; and the more weighty opinions are all in favour of the view that the use is neither increasing nor decreasing. It is true that during the last three years there has been a great development of the trade in charas, but the excess imports have for the most part passed over the Punjab into other provinces and territories, and only a portion of the increase appears from the figures to have stayed in the province. The figures in column 45 of the statement do not appear to be derived from accounts of actual retail sale. They are the exact difference of columns 12 and 16, and the explanatory note attached to the table shows that they are got by subtracting the exports from the imports. In saying that "it is one of the incidental advantages which we expect to derive from the proposed new arrangements that we shall be able to register the import trade efficiently and acquire a proper control over it," the Excise Commissioner appears to admit that the record of imports into the province is not reliable even yet. He considers the statistics of consumption fairly accurate. They were derived in 1892-93 from a comparison of the imports and exports in each district in order, as he says, to give reliable figures of the quantity retained in each district for consumption. But whatever method was employed in 1892-93 seems to have been also employed in previous years, for the figures in column 45 are throughout merely the difference between columns 12 and 16. The Commission therefore have considerable doubt as to the correctness of the figufes as indicating a steady increase to consumption for the last 13 years from 48o maunds to 1,020 maunds. This apparent increase may be due to improved methods of registration.

375. The Native States of the Punjab all lie, with the exception of Bahawalpur, in the eastern of the two halves into which the province is divided in reference to its habit of consuming charas. Leaving Bahawalpur out of consideration for the present, there is no reason to suppose that the States, either those which are wholly or partly in the Himalayas, or those which are in the plain, differ in any material respect from the British territory with which they are intermingled in regard to this habit. It hardly seems necessary to make any exception of the State of Nabha, where the hemp drugs are said to be prohibited. A continuous area of heavy consumption of charas is thus determined, comprising all those parts of the Punjab and North-Western Provinces lying between Lahore and Shahjahanpur. As regards bhang also, the description of the habit in the province must be held to apply to these States.

There is no official report from Bahawalpur, but the information which has been collected confirms the idea which is suggested by the position of the State, with reference to the Punjab and Sind, that it is a bhang-consuming country. Ganja is hardly used at all, and charas 'but little. The use of bhang is more common in the western than the eastern half of the State.

376. The figures of consumption of ganja given in paragraph 52 of the Excise Memorandum show since 1887-88 increase in every district except Hoshangabad and Narsinghpur. The decrease in these two districts is small ; the increase in several districts is large. There may have been some increase in the habit in this period-a point which will be discussed later on ; but the reports and evidence leave no doubt that the bulk of the increase in registered sale is due to improved administration and success in suppressing the use of the unexcised drug. This being the case, the figures of the last year, 1892-93, furnish a better basis for a survey of the consumption throughout the province than do the figures of any other year or of an average of years.

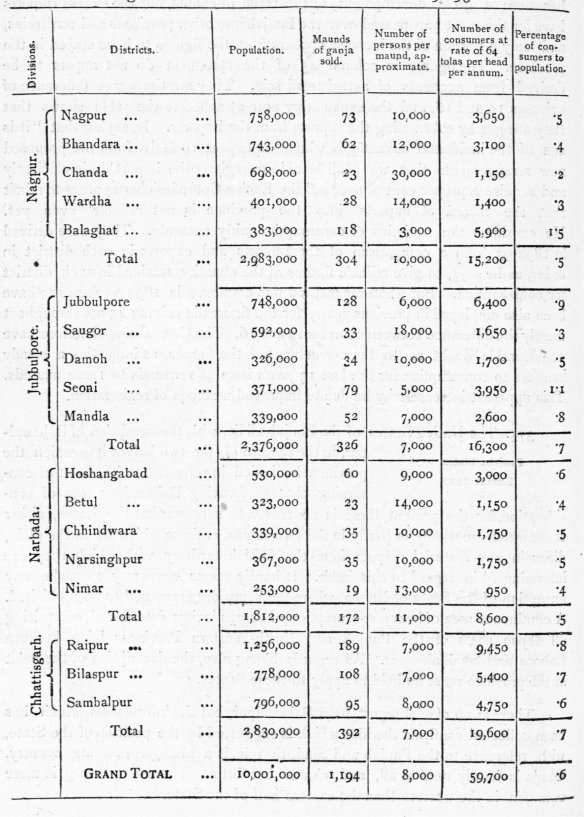

The following table contains the material statistics of 1892-93 :-

377 It will be seen from these figures that the area of heaviest consumption is the group of four districts, Balaghat, Seoni, Jubbulpore, and Mandla ; and among these Balaghat uses the drug at double the rate of the other three. Next in order come the districts of the Chhattisgarh Division. After these the other districts along the northern frontier, Damoh, Saugor, Narsinghpur, and Hoshangabad, with the addition of Chhindwara. Then follow the districts on the western and southern frontiers, Nimar, Betul, and Wardha, with Nagpur and Bhandara. And far behind comes the district of Chanda. The first two of the above groups consume the drug at a higher ratte han one maund to to,000 of the population ; the last three at less. Saugoris is included in the second group in spite of its apparently light consumption, because the large difference between it and the neighbouring district of Damoh in this respect confirms the evidence of illicit import given by reports and witnesses. Nagpur is placed in the fourth group in spite of its heavy sale compared with the other districts of the same group, because the consumption is to some degree foreign to the district, being connected with the troops at Kampti and other people who are attracted to the capital of the province. The high rate of consumption in Chhindwara, Seoni, Balaghat, and Mandla may probably be associated with their physical characteristics and their very malarious climate, for they cover the central highlands of the province—a tract of mountains and dense forest.

378. The evidence fixes the daily ration of ganja at about one-fourth of a tola. Making allowance for the custom of smoking in company, a lower rate ought probably to be adopted. And, on the other hand, the comparative cheapness and inferiority of the drug suggests a higher allowance than was thought appropriate for the Bengal calculations. The allowance of 64 tolas in the year, costing Rs. 5 to 8, or 50 consumers to the maund, appears to be a just medium. At this rate the number of consumers in the province would be about 6o,000. A considerable share of the excise ganja is used as 'bhang under the name of desi bhang. It seems to consist of the leaves and bracts, and often perhaps of the flowers themselves, picked off the ganja stalks. A reduction has to be made on this account if the number of smokers only is to be ascertained. On the other hand, some addition has to be made for the use of smuggled ganja. It will perhaps be sufficient to regard 6o,000 as the number of smokers of ganja, for the estimate does not pretend to exactness. This gives a percentage of 6 on the population of 10,000,000.

379 The evidence on the point of increase or decrease of use is very contradictory. In full view of many of the witnesses is the fact of the great and steady increase of the revenue and registered consumption in seven or eight districts, and their opinion as to the growth or decline of the use are doubtless affected by it. It has been stated above that the Commission attribute this increase for the most part to improved administration. Many witnesses hold this view, and none controvert it. But there are some who think that the extended use of the drug has materially contributed to the enhanced revenue. The Judicial Commissioner, Mr. Neill, has discussed the matter rather fully. He believes that the use has increased because (t) he is so informed by natives of sound and sober judgment ; (2) the consumption and revenue have been steadily growing up to date, whereas " if it was only that taxed ganja was substituted for untaxed and illicitly obtained ganja, the great increase would have shown itself in the earlier years after cultivation of the ganja-bearing plant was placed under restriction, imports watched, and all illicit cultivation severely punished ;" (3) the increase has occurred notwithstanding that the price of ganja has been raised to five times what it was in 1875-76 ; (4) as high a still-head duty as possible has been placed on liquor, and ganja is comparatively a cheap and convenient, because portable, stimulant ; and (5) the excise arrangements have advertised the drug and made it popular, and supplied a superior quality of it. These arguments include nearly all that have been urged by other witnesses, except the one that with those who seek a stimulant, the hemp drugs have the advantage over liquor that they are not prohibited by the Hindu religion. But after all Mr. Neill, like the vast majority of the witnesses all over India, appears not to speak from personal observation of the use. The evidence of Colonel Doveton, Conservator of Forests, is important as bearing upon the use of ganja among the jungle tribes. He describes this as more common than formerly. It is to be regretted that more information has not been furnished to explain the extraordinary high consumption in the Balaghat district, which must have a large population of the jungle tribes, and, it may be added, the great increase of the sale in the last five years. The construction of the Bengal-Nagpur Railway must have had considerable effect in the consumption of the districts through which it passes east of Balaghat. Special enquiries are being made by the Central Provinces Government regarding the increased consumption in the districts where it is most marked.

380. There are not wanting witnesses to assert that the use is on the decrease, and many believe that there is neither increase nor decrease. The statistics show that in ten districts there is either decrease or no very remarkable increase in the retail sale in the last five yeatts. But the Commission, looking to the balance of evidence supported by the statistics, cannot resist the conclusion that increased use accounts in some measure for the general growth of the revenue and registered consumption. They note that in more than one place the increase of revenue is attributed in part to the supply of a superior quality of drug. That the Khandwa drug is superior may be the case, but there is evidence that the local produce is preferred in the extreme east of the province, and it is in these regions that the greatest increase has occurred.

381. The supply of Khandwa ganja to the Feudatory States and zamindaris has steadily increased during the last ten years from 80 maunds to 273 (paragraph 66 of Excise Memorandum). The final figure represents a consumption by 13,65o smokers by the standard used for the calculations of the province. There is no evidence to show that the use has increased or decreased. The zamindars and feudatories had an ample supply of ganja of local growth before the Excise Department undertook to supply them, and it is pOssible that the old sources of supply of local growth are not yet quite closed, though the evidence shows the contrary.

382. In the Madras Presidency the only form of the drug which need be considered for the present purpose is ganja. Charas is only very exceptionally used, and there is no record of the amount imported. Bhang is not a distinct article from ganja. The liquid preparations, as well as the sweetmeats and electuaries, are made from ganja. Preparations of the latter class occupy a much more prominent place in the evidence of witnesses than they do in other parts of India, and this would suggest that they are in more common use.

383. The statistics furnished by the Madras Government give 67,000 sers as the retail sale of ganja for 1892-93. It has been ascertained that these are sers of 8o tolas, and the registered consumption is therefore 1,675 Indian maunds. In a previous chapter it was estimated that the share of the Madras produce which stayed at home was 3,500 maunds. A considerable reduction has to be made from this on account of waste to arrive at the amount which actually goes into consumption. The general tenor of the Madras evidence must also be noted. The same general unfamiliarity on the part of the witnesses with the facts relating to consumption which has been found more or less all over India exists in Madras also, and perhaps to a greater degree. The returns of retail sales obtained from the shops cannot represent more than a portion of the consumption of the Presidency, for there is ample evidence to show that the drug is freely handed about, and it has been admitted in official reports that the consumption is much larger than was supposed.

384. The figures of retail sale place the districts in the, following order as regards their rate of consumption : Madras, Kistna, Trichinopoly, Bellary, North Arcot, Tanjore, Malabar, Vizagapatam, Godavari, South Arcot, Madura, Salem, Cuddapah, South Canara, Coimbatore, Nellore, Tinnevelly, Chingleput, Ganjam, Anantapur, and Kurnool (Nilgiris no figures furnished). The evidence leaves the impression that the use is most common in the Northern Circars and gradually diminishes to the south until the Nilgiris are reached, where, according to some witnesses, the percentage of consumers on the population is high. The statistics and the evidence, therefore, do not agree ; for, according to the former, Ganjam takes a very low place, while some southern districts are high on the list. It appears, however, from the evidence that the people of the northern hill tracts prefer opium, and consume little of the hemp drugs. The latter are used principally in Vizianagram and the seapoit towns. The non-consuming population of the hill tracts would materially affect the rate of consumption as deduced from the figures. Kistna may owe its high position to other than strictly retail sales, as it is a district of production, and the same may be the case with North Arcot. Trichinopoly and Bellary have troops and probably heavy consumption in the cities to account for their retail sales being high. The position of Malabar is justified by the evidence as to the use in that part of the Presidency. The consumption of the City of Madras is probably indicated with fair accuracy by the figure of retail sale. It is lower than that of Bombay, which again is lower than that of Calcutta, the figures being—

|

Calcutta, one maund to |

••• ••• ••• |

1,400 |

|

Bombay |

••• ••• ••• |

2, 300 |

|

Madras |

••• ••• ••• |

4,900 |

385. Looking to the cheapness and comparative inferiority of Madras ganja, the average yearly allowance of the habitual consumer cannot be put at less than one full ser of 8o tolas, and the total number of regular consumers in the Presidency would then come to about 72,000, or -2 per cent. of the population. Attention has already been drawn to the apparent prevalence of the use of sweetmeats and other refined preparations concocted with ganja. The occasional use of these forms of the drug must extend to a very large share of the population over and above the number of regular consumers. There are also a certain number of drinkers of the liquid preparations.

386. The preponderance of evidence is decidedly in favour of the view that the use of the hemp drugs is increasing. The causes assigned for increase are generally the same as those mentioned in other provinces, the high price of liquor taking a prominent place among them. The Collectors, however, are generally of opinion that the use is stationary or decreasing. When decrease is alleged, it is in most cases attributed to the restrictions brought about by the excise arrangements, the raising of the price of the drug, and the limitation of the number of places where it can be bought. The statements of witnesses Nos. 131 and 155 may be consulted on this point. It has also been pointed out that stray cultivation is being discouraged, though it has not been formally prohibited. Thus there are causes operating to modify the extent of use in both directions, and the Commission do not think that the evidence enables them to say which are the more potent, or to judge in any way what the actual consumption is.

387. The Travancore import has been estimated at too maunds, which would be sufficient for 4,000 consumers. The use appears to be more prevalent in the hilly and malarious tracts. Some alleged increase is attributed to the relaxation of religious sentiment in regard to the use of intoxicants and communication with foreigners. The information regarding the other States furnishes no facts of special interest.

388. Ganja is used in all parts of the Bombay Presidency, a large share of the consumption of it being in the form of sweetmeats and drink. Bhang is used in the Bombay City and the Northern Division. Charas is smoked in the City of Bombay only, and that in very small quantity.

389. The figures of retail sale of ganja are wanting in some districts and irregular in others, so that it may be doubted if they can lay claim to accuracy even in the districts where they appear to be complete. Such as they are, they make the various districts take approximately the following order as regards their consumption of ganja : Dharwar, Bombay, Kanara, Bijapur, Nasik, Satara, Poona, Ahmedabad, Surat, Ahmednagar, B_elgaum, Broach, Sholapur, Khandesh, Panch Mahals, Kaira, and Ratnagiri.

390. There are no figures for Thana and Kolaba. The total of the district figures of retail sale taken out as far as practicable by five years' averages, with an allowance made for Thana and Kolaba, comes to about 3,800 maunds. The total consumption has been estimated in a previous chapter at maunds 3,000, and it was thought that this was a liberal calculation. .Before expressing any opinion from these figures as to the incidence of consumption on the population, it will be as well to examine the evidence as to individual consumption.

391. Mr. Almon, Assistant Collector of Abkari in Bombay, maintains that the moderate consumer of ganja spends two annas a day on his indulgence, and consumes one tola of the drug. This represents an annual consumption of over four sers and an expenditure of Rs. 45, and only admits of ten consumers being supplied by each maund of the drug. The average sale of 258 maunds, with allowance for waste, only suffices therefore for 2,000 or 2,50o consumers. Some witnesses, but they are few, state that the daily allowance of a moderate consumer is above one tola. The majority of witnesses put it at less. The lowest limit is reached by the Collector of Ratnagiri, who gives one-sixteenth of a tola as the average daily allowance, and reports 8,000 consumers in the district, of which the average retail sales amount to 74 maunds—i.e., more than ioo consumers per maund. The Collector of Ahmednagar has arrived at a mean of the above extremes. He caused " a hasty census to be taken throughout the district, " with the result that the number of consumers in a population of 888,755 was found to be 6,134, or •69 per cent. The Ratnagiri inquiries gave a percentage not very much, higher than the above, but by means of a much lower individual allowance. In Ahmednagar the allowance of 6,134 consumers on a total retail sale of 154 maunds comes to about 4o consumers to the maund, or one ser per head per annum, or somewhat less than a quarter of a tola per diem. The weight of evidence would fix the daily allowance nearer to one-half than one-quarter tola. Mr. Ebden's enumeration probably therefore included occasional consumers, and possibly counted- the same people more than once. The price of ganja outside Bombay ranges from three annas a pound in Satara to one anna a tola in Khandesh. One ser of ganja can never therefore cost more than Rs. 5, and the average price will be within the reach of all classes of consumers.

392. Making allowance for a considerable share of the drug being used in the making of drinks, sweetmeats, and other preparations, which are for the most part consumed only occasionally, and for waste, the number of regular consumers in British territory alone cannot be less than 2,500 X 30, or 75,000, giving a percentage on the population of -46. Besides these, there are the small body of regular drinkers of the hemp drugs and the occasional consumers of other preparations of the drug whose numbers cannot be estimated. The number of regular consumers in the Bombay City can hardly be less than 6,000.

393. Little reliance can be placed on the figures of retail sale, and in the present discussion they have only been utilised to range the districts in the order of their relative rate of consumption, and relied upon in the case of Ahmednagar because they were in fair accordance with the Collector's census of consumers and the experience gained in other provinces. The figures of retail sale in the Dharwar district are extraordinary. They show steady increase for years past, and have now reached a point which by the reasonable standard of individual consumption above adopted gives a percentage of over four of regular consumers on the population. This is impossible ; there is no such consumption as this in any rural tract in the whole of India. The witnesses who speak with special knowledge of the district do not give anything like this percentage, and they do not confirm the evidence of the figures that there has been a remarkable increase of consumption in the last fourteen years. The Collectorof Dharwar has endeavoured to ascertain the causes of this increase, and whether it is connected with the decline in the consumption of liquor and toddy. He reports that he can trace no connection between the two phenomena ; that there has been a large increase in the consumption of ganja, which is to be attributed to the introduction of the railway bringing with it scores of ganja smokers and eaters ; that there is no reason to suppose that the people of the district have generally taken to the use of the drug, though a number of individuals may have contracted the habit from foreigners ; and that there is no export of the drug. He attaches a statement showing that the retail sales of 1892-93 amounted to 1,345 maunds, an increase of more than 200 maunds over the figures of 1891-92. It is impossible to suppose that this huge amount can have been consumed in the district. It is larger than the whole consumption of the Central Provinces with its Feudatory States and zamindaris. The only reasonable explanation is that the greater part of it leaves the district, and enters the surrounding foreign territory, Hyderabad, Mysore, and Goa. The Kanara district also;may possibly get its supply from the Dharwar shops. The Dharwari ganja is not unknown, as the Commission found, in Mysore. This exaggeration in the Dharwar figures furnishes one more reason for distrusting those of other districts as an index of the local consumption.

394. On the point of general increase or decrease in the use of ganja, the responsible official witnesses, excepting the Collector of Bijapur, take the view that there is no perceptible change. On the other hand, there are witnesses of other classes who observe increase, and attribute it to the same economic and social causes as have been noticed in other provinces. But it may be noted that the high price of liquor does not take a prominent place among them, and many statements will be found to the effect that the hemp drugs are giving way to liquor. It cannot be said that there is a preponderance of the evidence either way or that there is any satisfactory basis for forming an opinion. The only causes of increase which can be assumed to have operated in the direction of increase are the increase of population and development of railways. The social causes would seem to tell both ways, education, however, being rather favourable to decrease of the habit than the reverse. The fact that the lower orders are addicted to liquor in the Bombay Presidency, and that their earnings are comparatively high and enable them to indulge this predilection, is a factor operating against increase of the hemp habit. Regarding bhang and charas, the tendency of the evidence is to show that the former is giving way to liquor ; the use of the latter, practically confined to the City of Bombay and insignificant in extent, shows no sign of increase.

395 The extent of use described in the Presidency may be accepted as applicable to the Native States under the supervision of the Bombay Government. There are no materials to enable a more exact estimate to be formed. In the Deccan and Southern Maratha Country ganja must be the favourite form of the drug, and in the Gujarat States, Kathiawar, and Cutch it is to a great extent superseded by bhang.

396. The statistics show that about 40 maunds of ganja and 4 of bhang are consumed in Aden, of which the population is 42,734. This gives the high rate of ganja consumption of one maund to i,000 of the population. The maximum price at which the contractor is allowed to sell is one anna a tola, and there is no minimum. The average price is probably much the same as that of the shops in the Presidency proper. If the Bombay rate of 3o consumers to the maund be taken, the consumers are about 3 per cent. of the population, or one man out of every 8 or ro. Considering the character of the population, composed to a great extent of Indian sepoys and the followers of native regiments, the high figure is not surprising. There is reason to think that service abroad induces a more liberal consumption of the hemp drugs among native regiments and their followers.

397• The average production of bhang in Sind and Khairpur is about 4,000 maunds. The statistics give the average retail sale of the British districts as 4,539 maunds, and this does not include the consumption of Karachi, for which district no figures of retail sale are given. The population and circumstances of Karachi compared with both those of Hyderabad justify the assumption that at least 5oo maunds are consumed in the former. The figure of total consumption of the province must be raised by this amount, and by r,000 according to the statistics for the State of Khairpur. But looking to the population of Khairpur, this consumption appears excessive, and the retail sale probably includes locally produced drug sold for consumption in other districts of Sind. So also it is probable that the retail sale of the Shikarpur district, where there is a considerable area of cultivation, includes the drug which has been exported. This district has not as high a figure of population as Hyderabad, and yet is credited with double the consumption. Hyderabad has but a trifling area of cultivation, and its figures of retail sale are probably a fairly accurate index of the consumption. They give one maund to 82o of the population, or say 800, allowing a few maunds for defective registration. This rate applied to the whole population of Sind with Khairpur, about 3,000,000, gives a total consumption of 3,75o maunds, which approximates to the estimate of production based on the area of cultivation. The statistics on a six years' average show that about 65o maunds of bhang are imported, mostly into the Shikarpur district. The estimated consumption, 3,750 maunds, therefore, only falls short of the total supply, 4,650 maunds, by 900 maunds, which is not an extravagant allowance for waste.

398. The average price of bhang is about Re. i a ser, and the average daily allowance I tola or about 4 sers per annum. A maund therefore supplies about 20 regular moderate consumers. But the majority of the consumers take the drtig only occasionally. The use in Sind—certainly in Upper Sind—is very like that of the Punjab and Northern India, where the beverage is drunk largely in the hot season, and to a comparatively small extent in the cold. It is probable that not more than one-third of the consumption can be credited to regular consumers, and that class would by this calculation number 1,250 x 20 = 25,00o. The occasional consumers are very many times more numerous, and may not improbably amount to between 5 and r o per cent. of the whole population. From this estimate the Thar and Parkar district is excluded, where the use of the drug is much less common than in the other districts of the province, its place being taken by opium.

399. The retail sale of charas, making an allowance of 5 maunds for Karachi, where there are no figures, is about 43 maunds. The import, however, averages 7o maunds. The consumption may be taken to be 50 maunds. The average daily allowance appears to be about 4 tola, or 2 ser per annum. There would then be about 2,000 charas smokers in the province, and these are all regular consumers. The cost at the above rate is Rs. t2-1 per annum, which is reasonable. The district of Shikarpur would seem to contain nearly half of the charas smokers.

400. The consumption of ganja is about the same as that of charas. The former is, however, the cheaper drug ; the individual consumption is probably therefore larger, and the smokers less numerous. The use is most prevalent in Karachi and Hyderabad, and may be said not to exist in Shikarpur and the Upper Sind Frontier. Thar and Parkar consumes more ganja than charas, hardly any of the latter.

401. The statistics do not furnish any reliable index of the growth or decline the use of either of the drugs. The evidence indicates increase, except in the case of ganja, but not very decidedly. The Commissioner (Mr. James) bears testimony by personal observation to the increase of the different classes of ascetics who principally are addicted to the drugs. Their number by the census of 1891 was 18,594. He is also of opinion that the use has spread among the labouring classes, whose wages have greatly risen in recent years. The addition to the population during the last 20 years, which amounts to over 3o per cent., must in the natural course of things have caused an increase of the total consumption.

402. The memorandum of the Hyderabad Assigned Districts throws doubt on the figures of retail sale of ganja contained in column 44 of the statistical table. They show an average comsumption in the last five years of some 800 maunds. They are fairly regular, and, but for the discredit thrown on them by the memorandum, seem fit to be accepted as an index of consumption. It is true that the local production and import together amount to 1,300 maunds. But the drug in this form contains a great deal of useless material, and it is probable that when sold retail 1,300 maunds get reduced to 800. This is not so large a proportion of waste as was found in the Central Provinces. The imported drug seems to come from Khandwa, and it is not likely that the local ganja is a more finished product than that imported. If the consumption of Berar is to be compared with that of the neighbouring Central Provinces, where the figures of retail sale represented the consumption of . the cleaned drug, it certainly cannot be taken to be more than 800 maunds ; and probably this is a high figure. In Berar the price of the drug is one-fourth of what it is in the Central Provinces. It is probable, therefore, that the individual allowance is very much higher. The evidence puts it at 1 tola a day, or approximately 2 sers per annum, which would cost Rs. 5. There would thus be 20 consumers to the maund and 16,000 in the province, giving a percentage of •55 on the total population. The result is not far different from that arrived at in the Central Provinces. As regards the result and individual cost, it appears to be reasonable. The evidence regarding increase and decrease of use is of the usual contradictory character. The statistics throw no light on the point, for they are not correct as regards the retail sales, and, as regards the imports, are not in a suitable form for the purpose. The preponderance of evidence is in favour of increase, but the direct observation of a witness like (31), who says that the younger men rarely smoke, must go for something. If the evidence of the majority be accepted, it is nevertheless certain that the increase is not very marked.

403. The reports and evidence from Ajmere-Merwara furnish no statistics to enable an estimate to be made of the extent of use of the hemp drugs. There was an increase of revenue in 1890-91 which was explained in the annual excise report to be due to competition at the auction of monopoly. There is no evidence of any increase or decrease of use.

404. In Coorg the import of ganja amounts to 21 maunds and registered consumption to 14. The population is 173,055. The retail price is 14 annas to 1 rupee for a ser of 24 tolas, or approximately 3 anna per tola. Taking the minimum individual allowance at tola or .1 anna per diem, the annual individual consumption comes to go tolas, and the cost to something less than Rs. 5. This is a reasonable allowance. The consumers would number about i,000, or between .5 and '6 per cent. of the population. It is probable that the consumption tends to increase with the influx of coolies into coffee and cardamom estates.

405. There is no information of the quantity of hemp drugs consumed in any part of Baluchistan. Bhang and ganja appear to come from India, and charas and chur ganja from Afghanistan as well as India. The Deputy Commissioner of Thal Chotiali reports that the Baluchis and Pathans of that district are not addicted to the drugs ; but there is information from other quarters that the Baluchis and Pathans generally do smoke. The drinking of bhang would appear to be confined to Pathans and Indians. It is said that the consumption of the drugs is decreasing as the Indian population, which was larger when military operations were going on, is being reduced. The average prices seem to be Re. t for bhang, Rs. zo for charas, and Rs. 78 for ganja per ser.

406. It has been shown that the hemp drugs, or ganja at least, are smuggled into Burma in considerable quantity. But it is impossible to say to what extent the Indians manage to supply their wants, or with any accuracy the price they have to pay for the drug. There does not seem to be any use by the Burmans or people other than the natives of India. The inquiries made by the Commission tend to show that the quantity introduced into the country is increasing.

407. It is hardly worth while to examine in detail the statistics and evidence relating to the extent to which the hemp drugs are used in the great Native States and Agencies. These territories are surrounded and intermingled with British territories, regarding which the question has been fully discussed, with the result that the statistics were found in most cases to be far from an accurate index of consumption, and the evidence did not justify very precise conclusions. More definite results, or equally definite, will certainly not be obtained from the information Supplied by Native States. The extent of use in each part of these territories may be taken to resemble that in the neighbouring British provinces. The use of ganja will be found to prevail over the States of the Central India Agency as it does in the North-Western Provinces, Bengal, and the Central Provinces. The use of bhang will be more common than that of the other drugs in Marwar and the north-western parts of Rajputana, and it will extend southwards towards the Bombay Presidency, and eastwards towards the States of Central India, gradually meeting with more competition from ganja. A moderate use of charas will be found all over the States which are within easy reach of the Punjab and the North-Western Provinces. The extent of use of ganja in Hyderabad will be fairly well indicated by the estimates of Berar, the Bombay Presidency, and Madras as regards the parts of the State contiguous to 'those provinces, and a similar process of examination will give the consumption of Mysore. In these two' States bhang as a separate form of the raw drug has practically disappeared, but charas finds a few consumers in Hyderabad. Baroda consumption is the same as that of the northern part of Bombay Presidency.

408. In Kashmir and Nepal the wild plant furnishes the whole, or a very large share, of the consumption—a fact which renders useless for present purposes the figure of production given in the Kashmir evidence, and of import from Bengal into Nepal which can be derived from the Bengal statistics.