| - |

Drug Abuse

MINISTRY OF HEALTH

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH FOR SCOTLAND

DRUG ADDICTION

Report of the

Interdepartmental Committee

LONDON

HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE

1961

INTERDEPARTMENTAL COMMITTEE ON DRUG ADDICTION

DEREK WALKER-SMITH,

Minister of Health.

3rd June, 1958.

*Now Sir Derrick Dunlop

INTERDEPARTMENTAL COMMITTEE

ON DRUG ADDICTION

REPORT

Minute of Appointment of the Committee

I hereby appoint:

Sir Russell Brain, Bart., M.A., D.M., F.R.C.P. A. Lawrence Abel, Esq., M.S., F.R.C.S.

*D. M. Dunlop, Esq., M.D., F.R.C.P.Ed., F.R.C.P., F.R.S.E. Donald W. Hudson, Esq., M.P.S.

A. D. Macdonald, Esq., M.Sc., M.D.

A. H. Macklin, Esq., O.B.E., M.C., T.D., M.D.

S. Noy Scott, Esq., M.R.C.S., L.R.C.P.

M. A. Partridge, Esq., M.A., D.M., D.P.M.

*D. M. Dunlop, Esq., M.D., F.R.C.P.Ed., F.R.C.P., F.R.S.E. Donald W. Hudson, Esq., M.P.S.

A. D. Macdonald, Esq., M.Sc., M.D.

A. H. Macklin, Esq., O.B.E., M.C., T.D., M.D.

S. Noy Scott, Esq., M.R.C.S., L.R.C.P.

M. A. Partridge, Esq., M.A., D.M., D.P.M.

to be a committee to review, in the light of more recent developments, the advice given by the Departmental Committee on Morphine and Heroin Addiction in 1926; to consider whether any revised advice should also cover other drugs liable to produce addiction or to be habit-forming; to consider whether there is a medical need to provide special, including institutional, treatment outside the resources already available, for persons addicted to drugs; and to make recommendations, including proposals for any administrative measures that seem expedient, to the Minister of Health and the Secretary of State for Scotland.

I hereby further appoint Sir Russell Brain to be Chairman, and Roy Goulding, Esq., M.D., B.Sc., and W. G. Honnor, Esq., I.S.O., to be Secretaries of the Committee.

I hereby further appoint Sir Russell Brain to be Chairman, and Roy Goulding, Esq., M.D., B.Sc., and W. G. Honnor, Esq., I.S.O., to be Secretaries of the Committee.

Minister of Health.

3rd June, 1958.

*Now Sir Derrick Dunlop

INTERDEPARTMENTAL COMMITTEE

ON DRUG ADDICTION

REPORT

To The Rt. Hon. J. Enoch Powell, M.B.E., M.P., Minister of Health.

The Rt. Hon. John Maclay, C.M.G., M.P., Secretary of State for Scotland.

Appointment

1. We were appointed on 3rd June, 1958, with the following terms of reference:

"to review, in the light of more recent developments, the advice given by the Departmental Committee on Morphine and Heroin Addiction in 1926; to consider whether any revised advice should also cover other drugs liable to produce addiction or to be habit-forming; to consider whether there is a medical need to provide special, including institutional, treatment outside the resources already available, for persons addicted to drugs; and to make recommendations, including proposals for any administrative measures that may seem expedient, to the Minister of Health and the Secretary of State for Scotland ".

Procedure

2. We have held eleven meetings. We decided as a first step to seek information from a number of organisations and persons having an interest in the questions before us and at a later stage we arranged for publication of a press notice inviting anybody interested to submit representations. We compiled a list of the points which we thought were of importance, but we made it clear that the replies need not be confined to these particular items. As a general rule we did not ask for oral evidence, though we found it an advantage in certain instances. Appendix I gives a list of the bodies and persons consulted. The Department of Health for Scotland, the Home Office and the Ministry of Health submitted evidence to us; officers of these Departments attended our meetings and have given us valuable assistance.

Interim Report

3. On 23rd November, 1959, we submitted an Interim Report. This dealt with two questions which arose from our terms of reference and which had been brought specially to our notice. First, we were asked to examine the risks attending the abuse of carbromal and bromvaletone and preparations containing these substances. The Poisons Board had already considered this problem but, in the absence of sufficient evidence that these compounds were widely abused, had not recommended them for control as "poisons" under the Pharmacy and Poisons Act, 1933.

4. On examination of the evidence it became clear to us that carbromal and bromvaletone were examples of a number of drugs on sale to the public which were not appropriate for restriction to supply on prescription under the Dangerous Drugs Act, 1951, or the Therapeutic Substances Act, 1956, and had not so far been recommended for control as poisons.

5. We recommended that, in general, any drug or pharmaceutical preparation which has an action on the central nervous system and is liable to produce physical or psychological deterioration should be confined to supply on prescription and that an independent expert body should be responsible for advising which substances should be so controlled.

6. As an interim and urgent measure, the Secretary of State for the Home Department, on the recommendation of the Poisons Board, has made Rules(1) under which certain substances having an action on the central nervous system are included in a new list of substances which may be sold by retail only on the prescription of a duly qualified medical practitioner, registered dentist, registered veterinary surgeon or registered veterinary practitioner.

7. We are glad to note the action that has been taken and we hope that arrangements will be made to ensure that, as other preparations affecting the central nervous system become available, they too will be brought to the notice of the Poisons Board, or such other advisory body as may in due course be appointed for the purpose, to consider whether there are sufficient grounds for restricting any of them also to supply on prescription.

8. The second part of our Interim Report was devoted to anaesthetists who become addicted to the gases and vapours which they use in the course of their professional duties. We ascertained that the incidence of this irregularity was very small indeed. However, over a period of eleven years, patients' lives had been endangered in two known instances.

9. We were assured by our expert witnesses on this subject that, with the apparatus at present to hand, the preliminary sniffing of the gases immediately before administering them to a patient was a recognised and indispensable precaution. We accepted this.

10. In view of the heavy and direct responsibility carried by every anaesthetist we were convinced that anyone addicted to the inhalation of gases and vapours should never be entrusted with their administration. Intervention in the first instance, we thought, should be by the anaesthetist's professional colleagues. The ethical questions arising have been discussed between Ministers and representatives of the medical profession and we are glad to see that a memorandum embodying the agreed arrangements was sent to hospital authorities in England and Wales on 27th May, 1960, and that one was sent to hospital authorities in Scotland on 18th August, 1960.

Report of the Departmental Committee on Morphine and Heroin Addiction (the "Rolleston Committee") 1926

11. The main tasks of the Rolleston Committee, whose advice we were invited to review, were to advise on:

(a) the circumstances, if any, in which the supply of morphine and heroin, and preparations containing these substances, to persons addicted to those drugs might be regarded as medically advisable;

(b) the precautions which medical practitioners administering or prescribing morphine or heroin should adopt to avoid abuse and any administrative measures that seemed expedient to secure observance of those precautions.

12. Through the system of records and inspection then in operation cases were brought to the notice of the Home Office at that time in which exceptionally large quantities of morphine and heroin had been supplied to particular practitioners or prescribed for individual cases. On further enquiry it was ascertained that sometimes the doctor had ordered these drugs simply to satisfy the craving of the addict; in some instances there was a doubt whether the supply was for bona fide medical treatment; in other cases the drugs had been prescribed in large quantities either to persons previously unknown to the practitioner or to a patient receiving supplies elsewhere; occasionally, large supplies had been used by practitioners for self-administration.

13. It appeared then that in some circumstances dangerous drugs were being supplied in contravention of the intention of Parliament that a doctor should be authorised to supply drugs only so far as was necessary for the practice of his profession. Before deciding on measures to secure proper observance of the law, it was felt necessary to have some authoritative medical advice on various aspects of the treatment of addiction, the use of dangerous drugs in medical treatment, and the action which might be taken where a doctor appeared to have misused his authority to possess and supply them.

14. The Rolleston Committee's recommendations in 1926 on the supply of morphine and heroin to addicts to these drugs and on the use of drugs in treatment are discussed later in this Report. They have, up to now, been included in the Memorandum on the Dangerous Drugs Act and Regulations which is prepared by the Home Office for the information of doctors and dentists.

15. As a result of the Rolleston Committee's proposals for administrative measures, amendments were made to the Dangerous Drugs Regulations in 1926 to the following effect :

(i)Provision was made for the constitution of a tribunal to which the Secretary of State could refer cases in which, in his opinion, there was reason to think that a duly qualified practitioner might be supplying, administering or prescribing drugs either for himself or other persons otherwise than as required for purposes of medical treatment.

(ii) The Secretary of State was empowered, on the recommendation of a tribunal, to withdraw a doctor's authority to possess and supply dangerous drugs and to direct that such a doctor, or a doctor convicted of an offence under the Act, should not issue prescriptions for dangerous drugs.

(iii) It was made clear that prescriptions should only be given by a duly qualified medical practitioner when required for purposes of medical treatment.

(iv) It was made an offence for a person who was receiving treatment from one doctor to obtain a supply of dangerous drugs from a second doctor without disclosing that he was being supplied by the first doctor.

(v) All doctors, dentists and veterinary surgeons were required to keep appropriate records of all dangerous drugs obtained.

With the exception of the provisions relating to tribunals, which we discuss later, all these amendments remain in the current regulations.

The changed situation

16. In the thirty-four years since the Rolleston Committee reported there have been developments in two directions which are of interest to our own Committee. On the one hand pharmaceutical research has produced a number of new analgesic drugs, many of which are capable of producing addiction. Some of these have been derived from opium and others have been produced synthetically. It is possible that many more addiction-producing drugs will be produced. A potent analgesic which is not addiction-producing has so far not been forthcoming. We have had to direct our attention to the question whether these drugs should be used with the same precautions and subjected to the same control as the morphine and heroin considered by the Rolleston Committee.

17. The second development has been in the methods of treatment of drug addiction. The withdrawal from addicts of the drug to which they are addicted has been the subject of experiment in several countries and particularly in the United States of America. These experiments have included the substitution of newer addiction-producing drugs and their subsequent gradual withdrawal, and also the use of other new drugs, such as tranquillizers, for the alleviation of the withdrawal symptoms. It has therefore been necessary to consider whether there are still circumstances in which the continued administration of dangerous drugs, even under the conditions strictly defined by the Rolleston Committee(2), can be justified.

18. We therefore had to consider:

(i) whether any new advice could be brought effectively to the notice of doctors and dentists;

(ii) whether the principles underlying the advice could be emphasised clearly to avoid misinterpretation;

(iii) whether any action was necessary to prevent the unjustifiable prescribing of dangerous drugs by some doctors;

(iv) whether there was any way of preventing the unjustified use of dangerous drugs by any doctor for himself or for members of his family ;

(v) the suggestion made in certain international organizations that Governments might set up special institutions for the treatment, care and rehabilitation of addicts on a compulsory basis.

19. In addition there has been an increase in the use by doctors and by the general public of drugs liable to cause habituation. Because they do not give rise to ill-effects substantially the same as, or analogous to, those produced by morphine or cocaine they are not within the scope of international agreements. We have considered this development.

Definitions adopted

20. From the outset we felt it necessary to have a clear and consistent idea of the phenomena confronting us. We therefore adopted the following definitions, realising that they are somewhat arbitrary and may need to be revised in the light of increasing knowledge.

Drug Addiction is a state of periodic or chronic intoxication produced by the repeated consumption of a drug (natural or synthetic); its characteristics include:

(1) an overpowering desire or need (compulsion) to continue taking the drug and to obtain it by any means,

(2) a tendency to increase the dose, though some patients may remain indefinitely on a stationary dose,

(3) a psychological and physical dependence on the effects of the drug,

(4) the appearance of a characteristic abstinence syndrome in a subject from whom the drug is withdrawn,

(5) an effect detrimental to the individual and to society.

Drug Habituation (habit) is a condition resulting from the repeated consumption of a drug. Its characteristics include:

(1) a desire (but not a compulsion) to continue taking the drug for the sense of improved well-being which it engenders,

(2) little or no tendency to increase the dose,

(3) some degree of psychological dependence on the effect of the drug, but absence of physical dependence and hence of an abstinence syndrome,

(4) detrimental effects, if any, primarily on the individual.

Sedative. A drug which depresses the central nervous system, especially at higher levels, so as to allay nervousness, anxiety, fear and excitement, but not normally to the extent of inducing sleep.

Hypnotic (or soporific). A drug used to induce sleep, which does so by depression of the central nervous system, more profoundly than a sedative but with a restricted duration of effect.

Tranquillizer (or Ataractic). A drug which promotes a sense of calmness and well-being without that degree of depression of the central nervous system commonly associated with the action of sedatives or hypnotics.

Stimulant. A drug which, by its action on the central nervous system, temporarily enhances wakefulness and alertness, improves mood and lessens the sense of fatigue.

21. In terms of physiology and pharmacology a narcotic is any agent which brings about a reversible depression of cellular metabolism and activity in the central nervous system. Substances included in any of the groups mentioned above, with the exception of the stimulants, may therefore be regarded as narcotics.

22. In more common parlance and in the proceedings of international agencies and control organisations the word "narcotic" is often limited to drugs like opium, morphine, heroin, pethidine, cocaine, etc., which are subject to measures of international control.

23. Alcohol was excluded from our considerations for the purpose of this report. We regard addiction to it as a serious problem which needs separate attention.

Extent of the problem in Great Britain

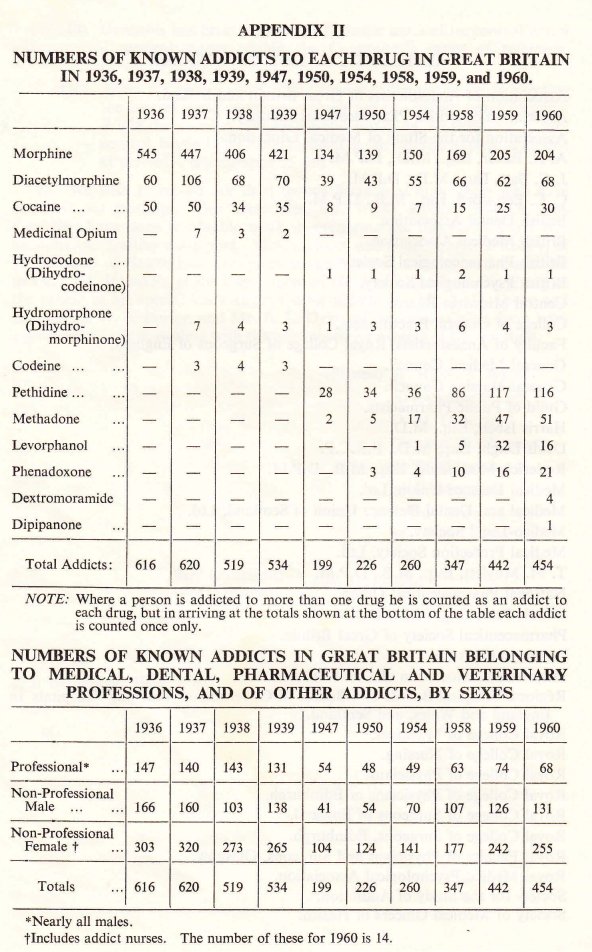

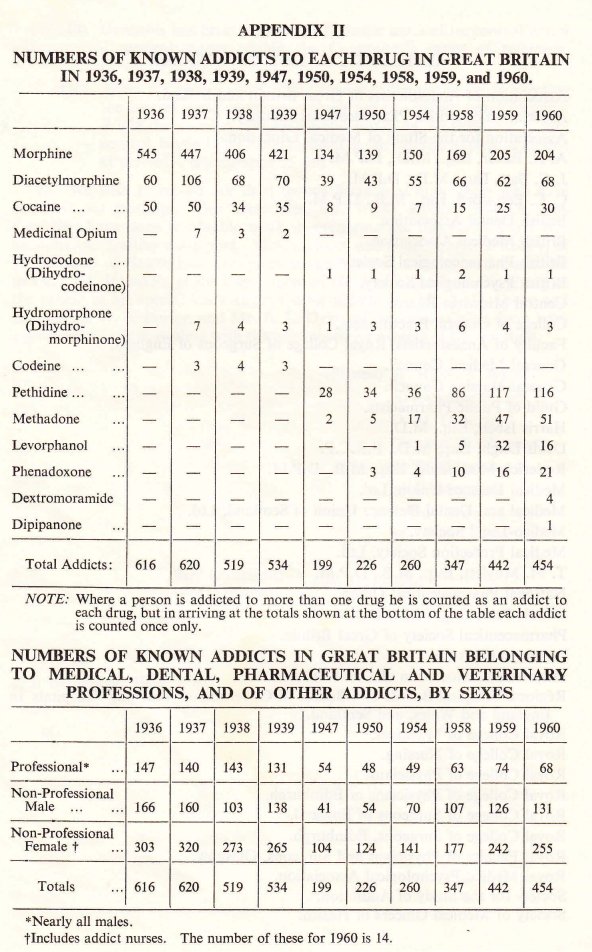

24. After careful examination of all the data put before us we are of the opinion that in Great Britain the incidence of addiction to dangerous drugs—which today comprise not only morphine and heroin but also such other substances coming within the provisions of the Dangerous Drugs Act, 1951, as pethidine, methadone, levorphanol, etc.—is still very small. The figures provided by the Home Office (see Appendix II) which might suggest an extension of addiction in Great Britain reflect, we think, an intensified activity for its detection and recognition over the post war period. At the same time the choice of drugs has altered, the new synthetics taken orally being now more popular. There is nevertheless in our opinion no cause to fear that any real increase is at present occurring. The number of doctors and nurses involved—the so-called "professional addicts"—though small in total, remains disproportionately high.

25. According to the Home Office and the police, supported by such independent evidence as we have been able to obtain, the purveying of illicit supplies of manufactured dangerous drugs for addicts in this country is so small as to be almost negligible. The cause for this seems to lie largely in social attitudes to the observance of the law in general and to the taking of dangerous drugs in particular, coupled with the systematic enforcement of the Dangerous Drugs Act, 1951 and its Regulations.

26. We would emphasise that there is, in Great Britain, no system of registration of addicts, nor any scheme by which the authorities allocate to them regular supplies of the drugs they are taking. We are, however, satisfied that the arrangements for recording manufacture and supply, and for inspection, continue to ensure that nearly all addicts ate known to the Home Office, to the Ministry of Health and to the Department of Health for Scotland.

Treatment

27. Like the Rolleston Committee, we believe that addiction should be regarded as an expression of mental disorder rather than a form of criminal behaviour.

28. We believe that every addict should be treated energetically as a medical and psychiatric problem. The evidence presented to us indicates that the satisfactory management of these cases is not possible except in suitable institutions. We are not convinced that compulsory committal to such institutions is desirable. Good results are more likely to be obtained with co-operative rather than with coerced patients. At a time when the compulsory treatment of the mentally sick is being steadily diminished we see no grounds for seeking new powers of compulsion for the treatment of drug addicts.

29. Judging by the expert advice offered to us we can see no advantage in abrupt withdrawal. Sudden and complete denial of the drug to the addict is a distressing and occasionally dangerous experience which it is best not to provoke. We do not think that we need draw up a plan of treatment, still less would we suggest that there is an ideal regimen which should be generally adopted. Yet, as this is a subject on which only a few doctors in Great Britain have any great personal experience, we have set out, in Appendix III, some notes that may serve as a guide.

Provision of institutions

30. Because the overall problem is so small it is doubtful whether there is scope for establishing specialised institutions in Great Britain exclusively for the treatment of drug addiction. We realise that at centres of this kind both medical and nursing staff would have an opportunity for training and research in the management of addicts, but very few patients would qualify for admission at any one time.

31. The best unit for the initial treatment of the established addict is, we consider, the psychiatric ward of a general hospital.

Long-term supervision and rehabilitation

32. Whereas withdrawal of the drug may be a fairly simple undertaking, long-term management, adequate rehabilitation and permanent cure present greater difficulties. Selected centres might undertake this long-term supervision and, at one or more of these, facilities for research might be provided, possibly by the Medical Research Council.

33. There remains the stage at which the addict returns to everyday life and consequently to the stresses which are liable to provoke a relapse. Social services are then required to offer all the help they can. Before the patient leaves hospital the general practitioner and, whenever appropriate, the local health authority as well, should be consulted about the provision of continued guidance and support. We recommend, too, that in every case the general practitioner should be notified immediately the patient leaves the hospital.

Prognosis

34. Information about the ultimate prognosis for drug addicts is extremely scanty and, so far as we can ascertain, the long-term results have hitherto been disappointing. This may reflect both the intractability of the condition and

the inadequacy of the treatment. Prevention, obviously, is to be preferred to cure and this leads us to acknowledge the prevailing healthy attitude of the public to this problem and the efficacy of the measures in Great Britain which keep the incidence of drug addiction to such small dimensions.

Administration of drugs to persons already addicted

35. The Rolleston Committee defined "circumstances in which morphine or heroin may be legitimately administered to addicts". These included "Persons for whom, after every effort has been made for the cure of addiction, the drug cannot be completely withdrawn, either because:

(i) Complete withdrawal produces serious symptoms which cannot be satisfactorily treated under the ordinary conditions of private(3) practice; or

(ii) The patient, while capable of leading a useful and fairly normal life so long as he takes a certain non-progressive quantity, usually small, of the drug of addiction, ceases to be able to do so when the regular allowance is withdrawn".

On the first of these points we have already stated (paragraph 28) that we believe only institutional treatment is likely to be satisfactory. With the second of these points we entirely agree, though the expression `regular allowance' has led to unfortunate and persistent misunderstanding. It has been taken in error to mean that addicts in Great Britain are entitled to receive supplies of dangerous drugs on prescription and that this involves the registration of the addict with some central authority. We think that the Rolleston Committee never meant to encourage a system of registration and from the evidence we have received it is clear that the Home Office have never acted in that belief and have never put such a system into force. The continued provision of supplies to patient addicts depends solely on the individual decision made by the medical practitioner professionally responsible for each case. We are strongly opposed to any suggestion that "registration" would be either desirable or helpful.

36. Arising also out of sub-paragraph (ii) quoted above is the conception of a "stabilised addict". The authenticity of this has been widely questioned. Many of those authorities and experienced persons who gave evidence to us nevertheless agree that this type of patient does exist. Moreover, a careful scrutiny of the histories of more than a hundred persons classsified as addicts reveals that many of them who have been taking small and regular doses for years show little evidence of tolerance and are often leading reasonably satisfactory lives. (See Appendix IV). Consequently we see no reason to reject the idea of a "stabilised addict". Indeed, to group together all "drug addicts" on the basis of a pharmacological definition may convey an over-simplified and misleading impression. There are drug addicts who have been introduced to the practice when physically healthy with drugs procured by illicit means or in the course of their professional work. This group is a very small one in Great Britain. There are those who, having been given a drug of addiction as the appropriate treatment for a painful illness, continue to be dependent on it when the original necessity for its use has disappeared. And there is a third group of those who are unable to abandon a drug rightly or wrongly prescribed for some physical or mental ailment which itself persists. Opinions may well differ as to whether those in the last group should be regarded as addicts, except in a technical sense, and where the line should be drawn between addiction to a drug and its appropriate medical use. Furthermore, we are impressed that the right of doctors in Great Britain to continue at their own professional discretion the provision of dangerous drugs to known addicts has not contributed to any increase in the total number of patients receiving regular supplies in this way.

Unjustifiable prescribing

37. Despite the generally satisfactory state of affairs we have been informed that from time to time there have been doctors who were prepared to issue prescriptions to addicts without providing adequate medical supervision, without making any determined effort at withdrawal and, notably, without seeking another medical opinion. Such action cannot be too strongly condemned. Only two such habitual offenders during the past twenty years have been brought to our notice and it is satisfactory to note that, in spite of widespread enquiry, no doctor is known to be following this practice at present.

Professional addicts

38. Among the known addicts are doctors who obtain and administer dangerous drugs to themselves. They take advantage of their privileged position to maintain their own addiction. Our enquiries reveal that only a few doctors in Great Britain are at present involved. Small though their numbers may be they present special problems.

Disciplinary measures

39. Under the Dangerous Drugs Regulations, 1953, as at present in force, the Home Secretary may withdraw from a doctor the authority which the Regulations give to all doctors to possess and supply dangerous drugs, if that doctor has been convicted of an offence against the Dangerous Drugs Act, 1951, or of certain Customs offences in respect of dangerous drugs and if the Home Secretary is of the opinion that that doctor may not properly be allowed to possess and supply them; he may also direct, if he withdraws the authority, that it shall not be lawful for that doctor to give a prescription for a dangerous drug.

40. A doctor who appears to be prescribing excessively for a particular patient may claim that he is doing so for adequate medical reasons. Without interfering with his professional freedom it would be difficult to contest such an assertion.

41. A doctor who decides that medically he requires the regular administration of dangerous drugs may lawfully obtain them for his own use by giving a prescription for that purpose, but he thereby attracts the attention of the authorities. Whether such self-administration or excessive prescribing, or the disorders of professional conduct to which it may lead constitutes infamous conduct in a professional respect is, in our opinion, a matter for the General Medical Council.

42. In 1926 the Rolleston Committee recommended that a tribunal should be established to investigate and decide whether, in particular cases, there were sufficient medical grounds for the administration of dangerous drugs by the doctor concerned either to a patient or himself. If a tribunal were to find to the contrary it would be able to advise the Home Secretary accordingly, and he would have power to withdraw the doctor's authority to possess and supply dangerous drugs without a previous conviction in the Courts. Although provision for these tribunals was made in the Dangerous Drugs Regulations, 1926, they never came into being, and when the new Regulations were promulgated in 1953 under the consolidated Dangerous Drugs Act of 1951, this provision was deferred pending completion of the negotiations which were then proceeding with the professional organisations.

43. The need for these tribunals has been urged upon us by some of our witnesses. We have been told that they have worked to advantage in Northern Ireland, but that they have now been discontinued in that country.

44. We are impressed by the difficulties of establishing a special tribunal for this purpose. There would be a need for powers to take evidence on oath, witnesses who are themselves addicts are notoriously unreliable and it might prove extremely hard to assess "sufficient medical grounds" in the face, possibly, of opposing medical opinions. Accordingly, after the most careful examination of this proposal, we have concluded that such special tribunals should not be set up in this country.

45. In general, we think that the infrequency of these irregularities fails to justify the introduction of further statutory powers to correct them. We strongly recommend, however, that every doctor should obtain a second medical opinion in writing before embarking on the regular prescribing of a dangerous drug, either to a patient, to a relative or to himself, for a lengthy period, say, in excess of three months. This would not interfere with the management of chronic cases, for example of inoperable carcinoma, as it must be very exceptional for such patients not to be seen by a consultant at some stage. To have, moreover, the support of another practitioner when dealing with an addict would, we feel, be welcomed rather than resented by the vast majority of doctors.

46. Further, we support the advice of the British Medical Association that a general practitioner should prescribe only a limited supply of a dangerous drug to a patient temporarily under his care in the absence of a letter from the patient's own doctor.

Distinctive prescription forms for Dangerous Drugs

47. We found little support for the suggestion that specially coloured or otherwise distinctive forms should be introduced for prescribing dangerous drugs. We see no advantage in this device, because in this country the problem of addiction is a small one, our present system of control works very efficiently and the additional work involved, both for doctors and for the Government, in the use and checking of special prescription forms, could not be justified. Moreover the use of such special forms might disclose to a patient that he was receiving dangerous drugs and it might be better for him not to know this.

Student instruction

48. In general we have come to the conclusion that students, during their undergraduate training, are adequately taught in most medical schools about the pharmacology and therapeutics of dangerous drugs and the risks of addiction to them, though the level of teaching varies considerably from one school to another. The note on addiction and habit-forming drugs which appears in the British National Formulary, 1960, is quite informative, but its scope could usefully be extended.

49. While not forgetting the need for medical students to be warned about the possibilities of addiction arising from the prescribing of dangerous drugs for medical reasons we are also aware that over-emphasis of this risk may sometimes lead to the withholding of powerful analgesics where the doctor's paramount duty is to relieve pain, and the possibility of addiction is virtually of no importance, e.g. in carcinoma.

Advice to the medical profession

50. The Home Office Memorandum(4) is accepted as fully comprehensive but it is thought that the essential features could be presented in a more readable form. It should be distributed, moreover, to all doctors in practice and not limited to general practitioners in the National Health Service.

Other drugs, beside morphine and heroin, likely to cause addiction

51. In 1926 the Rolleston Committee addressed itself solely to morphine and heroin. Today there is a whole range of analgesic drugs which may lead to addiction. These are readily brought within the purview of the Dangerous Drugs Act, 1951, and its Regulations and the arrangements by which this legislation is amended from time to time in accordance with International Conventions give rise to no difficulty. Moreover, the pharmaceutical organisations handling such drugs in this country co-operate so fully with the Home Office that there is at present no need for further statutory powers in this connection. The situation, however, should be kept under constant review.

52. There is some feeling that new potent analgesics should not be advertised or marketed to the medical profession until they have been subjected to an officially sponsored clinical trial and granted formal approval by some central authority. This proposal has received by no means universal support and we are not persuaded that it would be workable or wholly advantageous. We nevertheless think that no drug likely to be addictive should be released by the manufacturers until they have made sure that it has been carefully tested for this possibility.

53. So far as we can see at the moment all potent analgesics are likely to be addictive, whether they be old-established like morphine and heroin or new ones derived synthetically. Administratively they require the same control and medically they have the same indications and demand similar precautions in use to those outlined by the Rolleston Committee for morphine and heroin.

Cannabis

54. In our view cannabis is not a drug of addiction: it is an intoxicant. Nevertheless it comes within the scope of the Dangerous Drugs Act, 1951. But having virtually no place in therapeutics it is obtained almost solely through illicit channels and there has been some rise in the annual amount seized by the Customs authorities. We have not received evidence that its use constitutes a medical problem. Even if its social consequences should give rise to concern, which we would share with the authorities who are responsible for the suppression of traffic in this drug, we see no indication for further administrative measures within our own terms of reference.

Habit-forming drugs

55. Over recent years an intensive interest has developed, both experimentally and clinically, in drugs affecting the central nervous system. These include sedatives, hypnotics, tranquillizers and stimulants. The impression has been formed that medically they are now used on a very large scale.

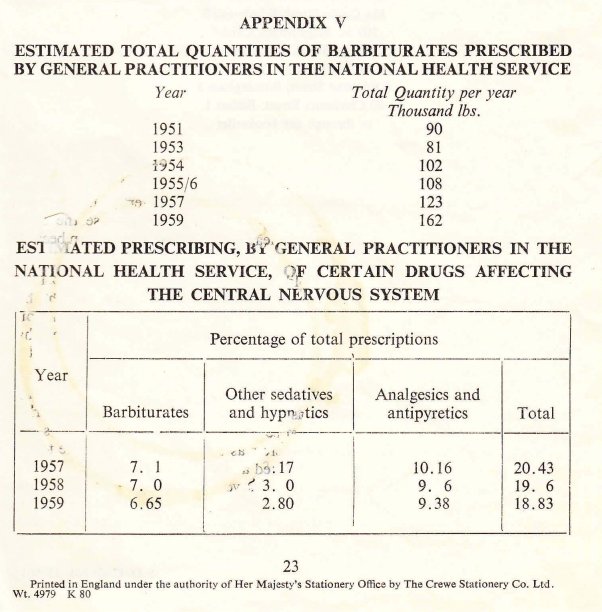

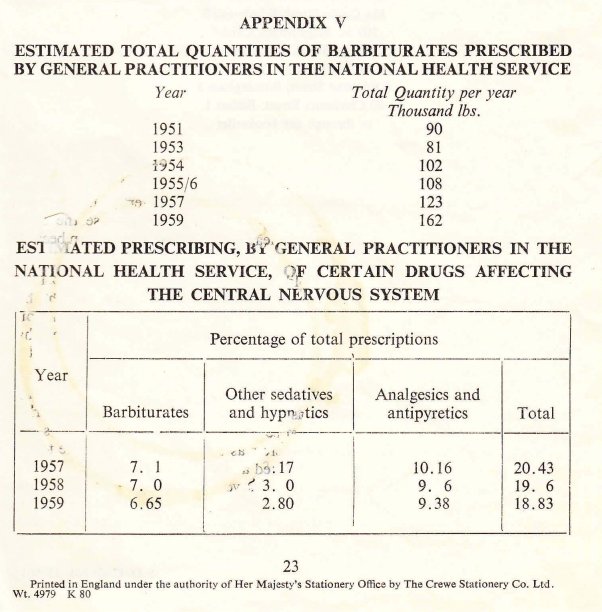

56. Most of our witnesses affirmed that, today, drugs acting on the central nervous system are being used excessively, but they were unable to furnish records in support of this contention. We have therefore endeavoured to obtain some evidence. From a sample of the prescriptions issued under the National Health Service we have been provided with an estimate of the total quantity of barbiturates prescribed annually in England and Wales over the past few years (Appendix V). It is obvious that usage has expanded both progressively and substantially so that in 1959 it was almost twice what it was in 1951. Total production figures, though they of course include exports as well, confirm this trend. Secondly, by an analysis of National Health Service prescriptions according to therapeutic classification it can be seen that barbiturates, other sedatives and hypnotics, together with analgesics and antipyretics (excluding dangerous drugs) account for no less than about nineteen per cent of all the prescriptions issued (Appendix V).

57. For the tranquillizers we have no corresponding figures. There is reason to believe, however, that their prescription has also increased. Certainly the amount spent on one particular tranquillizer by nine selected mental hospitals has increased about ten-fold over a course of five years. The scale of use of tranquillizers in general practice we have not been able to ascertain. One reason for this has been that as such drugs are not readily subject to therapeutic classification their handling in a sample analysis is difficult.

58. Less still have we any definite information about the volume of purchases without prescription. We believe, however, that the action which followed our Interim Report will have reduced this self-medication, at least so far as the more potent drugs acting on the central nervous system are concerned.

59. The abuse of stimulant drugs such as the amphetamines and phenmetrazine has led to some publicity and concern. We know that cases of habituation and addiction occur. Although at least forty-eight cases of amphetamine addiction and a few of phenmetrazine addiction have been reported in the medical literature because of their having presented with severe (though transient) mental disorder, there are no figures available to indicate the actual extent to which such habituation or addiction may occur, with or without overt mental symptoms.

60. An analysis of some 214,000,000 National Health Service prescriptions in 1959 indicated that some 5,600,000, or approximately 21 per cent, were for preparations of the amphetamines and phenmetrazine. Since the indications for the use of these substances are not clear cut, it may be that such prescribing is excessive, though hardly to an extent that could give rise to concern. We have formed the impression that, while serious cases of addiction arise from time to time, such abuse is not widespread. Precautions have already been taken to prevent those intent on abuse from having access without prescription to preparations of the amphetamines and phenmetrazine and to what was formerly a ready source of supply, namely the inhalers containing paper impregnated with amphetamine in concentrated form.

61. It is clear that there is scope and a need for operational research into the prescribing pattern in this country, with particular reference to habit-forming drugs. The results of such a study could be enlightening to the public.

62. To explain this trend in medication directed at the central nervous system we have found no single answer. In part it must be due to the vigorous advertising of these drugs and their preparations by the pharmaceutical industry, both to the medical profession and to the public. To some extent the accelerated tempo and heightened anxieties of modern life have been held to blame, but this is an assertion based on assumption more than fact. Thirdly, and possibly of considerable consequence, there is the materialistic attitude adopted nowadays to therapeutics in general This is one feature of an age which owes so much to science. For every deviation from health, great or small, a specific, chemical corrective is sought and, if possible, applied, and it is also widely believed that health may be positively enhanced by the use of drugs. When dealing with mental disease psychotherapy may still be invoked. Often, however, a prescription is given for a drug when the patient's real need is a discussion of his psychological difficulties with the doctor. An obvious danger arises when the drugs so employed, far from being placebos, are undeniably potent, frequently toxic and sometimes habit-forming as well. On the other hand the newer drugs are proving of great value in psychiatry where they are to some extent replacing other methods of treatment.

63. This increasing use of sedatives, stimulants and tranquillizers raises issues upon which we do not as a Committee feel competent to pronounce. In particular, it is not for us to decide whether their occasional or even regular use is justified if it enables a person to lead a happier and more useful life. In any case, if recourse to potentially habit-forming drugs is sometimes to be regarded as a symptom of psychological maladjustment, it should be treated as a symptom, and its cause sought, perhaps as much in social conditions as in the mind of the individual. These are questions which should be considered not only by doctors, but by all concerned with social welfare.

64. The argument has been advanced that the availability of these drugs to so many people nowadays leads to their frequent use for suicide. Over recent years, certainly, the barbiturates have figured more prominently in this connection. At the same time the total suicide rate has remained almost unchanged. It looks, therefore, as though suicide itself has not become more popular, even if the means of achieving it have altered, and it must be borne in. mind that the therapeutic use of barbiturates and tranquillizers may well have saved many people from suicide.

65. The management of mental disorder generally has also been brought to our notice. The pattern seems to have changed considerably over recent years. Community care is taking the place of institutional confinement. More patients can be treated at home and many of them enabled to take an active and useful part in life. If the prescribing of even habit-forming drugs has contributed to this state of affairs it is to be condoned rather than condemned

66. We think that the position may require careful watching as time goes on but, at the moment, we see no grounds for suggesting further statutory control over habit-forming drugs, other than that recommended in our Interim Report.

Summary of conclusions and recommendations

67. The following is a summary of our conclusions and recommendations.

(1) In Great Britain the incidence of addiction to drugs controlled under the Dangerous Drugs Act, 1951, is still very small and traffic in illicit supplies is almost negligible, cannabis excepted. This is mainly due to the attitude of the public and to the systematic enforcement of the Dangerous Drugs legislation. (Paragraphs 24, 25 and 54).

(2) While there is no registration of addicts, nor any official allocation of drugs to them on that basis, the Departmental arrangements ensure that nearly all addicts to dangerous drugs are known. (Paragraph 26).

(3) Addiction should be regarded as an expression of mental disorder, rather than a form of criminal behaviour. (Paragraph 27).

(4) Satisfactory treatment of addiction is possible only in suitable institutions, but compulsory committal of an addict to such an institution is not desirable. (Paragraph 28).

(5)There is no advantage in abrupt withdrawal of a drug from a patient. Notes on treatment are given as a guide. (Paragraph 29 and Appendix III).

(6) As the problem is small, the establishment of specialised institutions exclusively for the treatment of drug addiction is not practicable. Initial treatment of an established addict is best undertaken in the psychiatric ward of a general hospital. (Paragraphs 30 and 31).

(7)Long term supervision would best be undertaken at selected centres, at which facilities for research might be provided. (Paragraph 32).

(8) Continued support and guidance should be available locally when a patient leaves hospital. (Paragraph. 33).

(9) Long term results of treatment of addiction appear to be disappointing, but the information available is limited. (Paragraph 34).

(10) A system of registration of addicts would not be desirable or helpful. (Paragraph 35).

(11) It is doubtful whether a person who is unable to abandon a drug originally prescribed for a condition which still persists should be described as an addict. It is accepted that such a person may be able to lead a reasonably satisfactory life on a small and regular dose of a narcotic drug but may be unable to do so if it be withdrawn. (Paragraph 36).

(12) The Home Secretary should not establish medical tribunals to investigate the grounds for recommending him to withdraw a doctor's authority to possess and supply dangerous drugs. (Paragraph 44).

(13) Irregularities in prescribing of dangerous drugs are infrequent and would not justify further statutory controls. (Paragraph 45).

(14) A doctor should obtain a second medical opinion before deciding to prescribe a dangerous drug for a lengthy period; and should give only a limited supply of a dangerous drug to a patient temporarily under his care in the absence of a letter from the patient's own doctor. (Paragraphs 45 and 46).

(15) No advantage would arise from the use of distinctive prescription forms for dangerous drugs. (Paragraph 47).

(16) Student instruction on dangerous drugs is generally adequate; but over-emphasis on the dangers of addiction may discourage the use of such drugs in cases where their need is paramount. (Paragraph 49).

(17) The essential features of the Home Office Memorandum on Dangerous Drugs could be presented in a more readable form. It should be sent to all doctors in practice. (Paragraph 50).

(18) Further statutory powers to control new analgesic drugs are not needed at present. There is insufficient justification for withholding them from distribution until they have been approved by some central authority, but any drug likely to be addictive should be tested for this possibility at the instance of the manufacturers before release. (Paragraphs 51 and 52).

(19) Cannabis has practically no therapeutic use and its control is not a medical matter within the Committee's terms of reference. (Paragraph 54).

(20) There has been a substantial increase in the use of drugs affecting the central nervous system, which are potentially habit forming. While the position requires careful watching, no further statutory control, beyond that recommended in our Interim Report, is needed at present. (Paragraphs 55-66).

8. We wish to record our debt to our Secretariat and others who have attended our meetings. Our Secretaries, Mr. W. G. Honnor and Dr. Roy Goulding have done invaluable work in preparing the material for our discussions and drafting our report. Mrs. J. Hauff, and later Mr. H. N. Roffey, of the Ministry of Health have also given us much assistance, and we are grateful to Dr. J. M. Johnston, of the Department of Health for Scotland, for giving us the benefit of his special knowledge of drug addiction. Mr. T. C. Green and later Mr. S. H. E. Burley, and Mr. A. L. Dyke, of the Home Office, have been a great help to us in dealing with the administrative aspects of the question.

(1) The Poisons Rules 1960 (S.I. 1960, No. 699).

(2) See paragraph 35

(3) In this context " private practice" may be read as " general practice."

(4) See Paragraph 14 of this Report.

(Signed)

W. RUSSELL BRAIN

A. LAWRENCE ABEL

D. M. DUNLOP

DONALD W. HUDSON

A. D. MACDONALD

A. H. MACKLIN

S. NOY SCOTT

MAURICE PARTRIDGE

ROY GOULDING - W. G. HONNOR Joint Secretaries

29th November, 1960

Association of British Pharmaceutical Industry. Association for the Study of Medical Education. A. A. Baker, Esq., M.D., D.P.M.

J. C. Batt, Esq., M.D., D.P.M.

C. C. Beresford, Esq., M.B., D.P.M. British Dental Association.

British Medical Association.

British Pharmacological Society

British Psychological Society.

Central Midwives Board.

College of General Practitioners.

Faculty of Anaesthetists, Royal College of Surgeons of England.

General Medical Council.

General Nursing Council.

Guild of Public Pharmacists.

Harris Isbell, Esq., M.D.

Denis Leigh, Esq., M.D., F.R.C.P. Roderick Macdonald, Esq., M.B., D.P.M. Medical Defence Union, Ltd.

Medical and Dental Defence Union of Scotland, Ltd.

Medico-Legal Society.

Medical Protection Society, Ltd.

T. M. Moylett, Esq., M.B., D.P.M. National Pharmaceutical Union.

Dennis Parr, Esq., M.D., D.P.M.

Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. Prison Commission.

Proprietary Association of Great Britain.

Regional Hospital Boards and Boards of Governors of Teaching Hospitals in

England and Wales, and Scotland. Royal College of Midwives.

Royal College of Nursing.

Royal College of Physicians.

Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. Royal College of Surgeons of England. Royal College of Surgeons, Edinburgh.

Royal Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons, Glasgow.

Royal Medico-Psychological Association. Society for the Study of Addiction. Society of Medical Officers of Health.

1. Withdrawal of the Drug. This should be carried out in an institution, preferably in the psychiatric ward of a general hospital. Abrupt withdrawal offers no advantages. The abstinence syndrome is seldom fatal, but it causes the patient severe discomfort which is better avoided.

After a preliminary physical and psychiatric examination withdrawal is graduated according to the previous intake of drugs and the patient's physical condition. For the young and fit person on a small dosage this period may extend over no more than one or two days; for the elderly and, especially, the person with serious heart disease, it may be prolonged for a month.

The most likely psychiatric complication is depression, with a risk of suicide.

Almost any opiate or synthetic equivalent may be used in substitution. Methadone has the merits of being effective orally so that hypodermic injections are eliminated, two doses per day are sufficient in view of its length of action and the symptoms of withdrawal are less strong than with, say, morphine. Dosage of the substitute narcotic is adjusted initially to that which leaves the patient mildly, but not entirely, uncomfortable. Then it is reduced gradually over a period that may range from 3 to 30 days. The maximum quantity of methadone required for this purpose is not more than 60 mg. twice daily at the outset; more often it is 10 to 30 mg. twice daily.

The patient should receive a light diet, ample fluids, suitable means of keeping himself occupied and, in some instances, hydrotherapy. Heavy sedation is best avoided, and the risk of dependence on barbiturates as an alternative to the original addiction must be borne in mind.

2. Convalescence. After withdrawal the patient may have various complaints, particularly of insomnia and disturbances of mood. Sedatives are best avoided. Exercise and occupation are valuable.

3. Physical Rehabilitation. Any physical disease from which the patient is suffering should be treated from the beginning. Chronic causes of pain should be eliminated if at all possible, surgical measures being taken where indicated.

4. Psychotherapy. Supportive psychotherapy is essential. It may be conducted as a group procedure.

5. Occupational Therapy. As far as possible this should take the form of useful work with increasing responsibility and need for application.

6. Recreational Therapy. Library services, cinema, games and television should be provided to keep the patient constantly interested and his mind exercised.

7. Length of Treatment. No arbitrary figure can be set for this, which depends on the individual patient's personality and character, the length and severity of his addiction, and the possible arrangements which can be made for his future.

8. After-care. The stage at which the patient returns to the community and, perhaps, to his old surroundings and acquaintances, is a crucial one. Employment, unpaid or otherwise is almost always indicated and regular consultations are likely to be essential.

In drawing up these notes on treatment the Committee gratefully acknowledges its debt to Dr. Harris Isbell of the National Institute of Health Addiction Research Centre, Lexington, Kentucky, U.S.A., who gave his evidence and advice from the very extensive experience which he has had in this subject.

2. Mrs. B., also a housewife, and well past middle age, has been troubled for over ten years with very severe varicose ulceration of the leg. This has not been improved by conventional treatment. The pain has not been mitigated by antipyretic analgesics. For about five years she has received 5 tablets of pethidine, each of 50 mg., daily. This enables her to carry out her duties as a housewife and to look after members of her family suffering from severe disease and psychoneuroses. There has been no need to increase the dose, but when the drug is withheld the patient pleads that she cannot carry on because of the pain.

3. Mrs. C., a housewife, is an old lady, and a life-long neurotic person. Suspected of a crush-fracture in the mid-thoracic region after a fall she has complained of constant pain despite a spinal support. With four methadone tablets, each of 5 mg., per day she manages her household duties. There has been no plea to increase the dose. On the other hand withdrawals have led to such a reaction that the home and family have suffered.

4. Mr. D. is past middle age; he is employed in the office of a large manufacturing firm. For many years he has suffered from generalised osteoarthritis. He has had advice and treatment from several consultants. Some year ago levorphanol was prescribed. At first there was a tendency for the dose to rise but, for about five years now it has remained at 3 tablets, each of 1. 5 mg., daily. Attempts have been made at withdrawal on several occasions. There has been no abstinence syndrome, but the patient's pain has returned with a severity sufficient to stop him working. So long as he is given his tablets he seems to be capable of a hard responsible full day's work.

5. Mrs. E. is a manic-depressive of middle age. Her persistent symptom is low back pain for which she has had operations. In addition she has exhibited pseudo-cyesis and has been an in-patient in a mental hospital. Her record includes reports from very many consultants.

Nine years ago she was treated with pethidine. A year-and-a-half later this was changed to methadone, the dose of 10 mg. every six hours having remained unchanged all this time. On this quantity she does all her own housework. In her better phases she has voluntarily reduced the dosage temporarily to some extent. When, however, the drug was withdrawn altogether during the time that she was an in-patient at the mental hospital a profound nervous disturbance immediately followed.

6. Mr. F. is described as a clerical worker past middle age. He suffers from a painful disease which has necessitated the amputation of limbs. For several years he has received analgesics for his pain, first pethidine and subsequently phenadoxone. Over the last four years his dose of phenadoxone has been steady at the rate of twenty 10 mg. tablets daily. On this quantity he appears to have shown no mental deterioration; on the contrary he continues to work responsibly. When other, non-addictive drugs have been substituted from time to time, his pain has returned with renewed severity.

The Rt. Hon. John Maclay, C.M.G., M.P., Secretary of State for Scotland.

Appointment

1. We were appointed on 3rd June, 1958, with the following terms of reference:

"to review, in the light of more recent developments, the advice given by the Departmental Committee on Morphine and Heroin Addiction in 1926; to consider whether any revised advice should also cover other drugs liable to produce addiction or to be habit-forming; to consider whether there is a medical need to provide special, including institutional, treatment outside the resources already available, for persons addicted to drugs; and to make recommendations, including proposals for any administrative measures that may seem expedient, to the Minister of Health and the Secretary of State for Scotland ".

Procedure

2. We have held eleven meetings. We decided as a first step to seek information from a number of organisations and persons having an interest in the questions before us and at a later stage we arranged for publication of a press notice inviting anybody interested to submit representations. We compiled a list of the points which we thought were of importance, but we made it clear that the replies need not be confined to these particular items. As a general rule we did not ask for oral evidence, though we found it an advantage in certain instances. Appendix I gives a list of the bodies and persons consulted. The Department of Health for Scotland, the Home Office and the Ministry of Health submitted evidence to us; officers of these Departments attended our meetings and have given us valuable assistance.

Interim Report

3. On 23rd November, 1959, we submitted an Interim Report. This dealt with two questions which arose from our terms of reference and which had been brought specially to our notice. First, we were asked to examine the risks attending the abuse of carbromal and bromvaletone and preparations containing these substances. The Poisons Board had already considered this problem but, in the absence of sufficient evidence that these compounds were widely abused, had not recommended them for control as "poisons" under the Pharmacy and Poisons Act, 1933.

4. On examination of the evidence it became clear to us that carbromal and bromvaletone were examples of a number of drugs on sale to the public which were not appropriate for restriction to supply on prescription under the Dangerous Drugs Act, 1951, or the Therapeutic Substances Act, 1956, and had not so far been recommended for control as poisons.

5. We recommended that, in general, any drug or pharmaceutical preparation which has an action on the central nervous system and is liable to produce physical or psychological deterioration should be confined to supply on prescription and that an independent expert body should be responsible for advising which substances should be so controlled.

6. As an interim and urgent measure, the Secretary of State for the Home Department, on the recommendation of the Poisons Board, has made Rules(1) under which certain substances having an action on the central nervous system are included in a new list of substances which may be sold by retail only on the prescription of a duly qualified medical practitioner, registered dentist, registered veterinary surgeon or registered veterinary practitioner.

7. We are glad to note the action that has been taken and we hope that arrangements will be made to ensure that, as other preparations affecting the central nervous system become available, they too will be brought to the notice of the Poisons Board, or such other advisory body as may in due course be appointed for the purpose, to consider whether there are sufficient grounds for restricting any of them also to supply on prescription.

8. The second part of our Interim Report was devoted to anaesthetists who become addicted to the gases and vapours which they use in the course of their professional duties. We ascertained that the incidence of this irregularity was very small indeed. However, over a period of eleven years, patients' lives had been endangered in two known instances.

9. We were assured by our expert witnesses on this subject that, with the apparatus at present to hand, the preliminary sniffing of the gases immediately before administering them to a patient was a recognised and indispensable precaution. We accepted this.

10. In view of the heavy and direct responsibility carried by every anaesthetist we were convinced that anyone addicted to the inhalation of gases and vapours should never be entrusted with their administration. Intervention in the first instance, we thought, should be by the anaesthetist's professional colleagues. The ethical questions arising have been discussed between Ministers and representatives of the medical profession and we are glad to see that a memorandum embodying the agreed arrangements was sent to hospital authorities in England and Wales on 27th May, 1960, and that one was sent to hospital authorities in Scotland on 18th August, 1960.

Report of the Departmental Committee on Morphine and Heroin Addiction (the "Rolleston Committee") 1926

11. The main tasks of the Rolleston Committee, whose advice we were invited to review, were to advise on:

(a) the circumstances, if any, in which the supply of morphine and heroin, and preparations containing these substances, to persons addicted to those drugs might be regarded as medically advisable;

(b) the precautions which medical practitioners administering or prescribing morphine or heroin should adopt to avoid abuse and any administrative measures that seemed expedient to secure observance of those precautions.

12. Through the system of records and inspection then in operation cases were brought to the notice of the Home Office at that time in which exceptionally large quantities of morphine and heroin had been supplied to particular practitioners or prescribed for individual cases. On further enquiry it was ascertained that sometimes the doctor had ordered these drugs simply to satisfy the craving of the addict; in some instances there was a doubt whether the supply was for bona fide medical treatment; in other cases the drugs had been prescribed in large quantities either to persons previously unknown to the practitioner or to a patient receiving supplies elsewhere; occasionally, large supplies had been used by practitioners for self-administration.

13. It appeared then that in some circumstances dangerous drugs were being supplied in contravention of the intention of Parliament that a doctor should be authorised to supply drugs only so far as was necessary for the practice of his profession. Before deciding on measures to secure proper observance of the law, it was felt necessary to have some authoritative medical advice on various aspects of the treatment of addiction, the use of dangerous drugs in medical treatment, and the action which might be taken where a doctor appeared to have misused his authority to possess and supply them.

14. The Rolleston Committee's recommendations in 1926 on the supply of morphine and heroin to addicts to these drugs and on the use of drugs in treatment are discussed later in this Report. They have, up to now, been included in the Memorandum on the Dangerous Drugs Act and Regulations which is prepared by the Home Office for the information of doctors and dentists.

15. As a result of the Rolleston Committee's proposals for administrative measures, amendments were made to the Dangerous Drugs Regulations in 1926 to the following effect :

(i)Provision was made for the constitution of a tribunal to which the Secretary of State could refer cases in which, in his opinion, there was reason to think that a duly qualified practitioner might be supplying, administering or prescribing drugs either for himself or other persons otherwise than as required for purposes of medical treatment.

(ii) The Secretary of State was empowered, on the recommendation of a tribunal, to withdraw a doctor's authority to possess and supply dangerous drugs and to direct that such a doctor, or a doctor convicted of an offence under the Act, should not issue prescriptions for dangerous drugs.

(iii) It was made clear that prescriptions should only be given by a duly qualified medical practitioner when required for purposes of medical treatment.

(iv) It was made an offence for a person who was receiving treatment from one doctor to obtain a supply of dangerous drugs from a second doctor without disclosing that he was being supplied by the first doctor.

(v) All doctors, dentists and veterinary surgeons were required to keep appropriate records of all dangerous drugs obtained.

With the exception of the provisions relating to tribunals, which we discuss later, all these amendments remain in the current regulations.

The changed situation

16. In the thirty-four years since the Rolleston Committee reported there have been developments in two directions which are of interest to our own Committee. On the one hand pharmaceutical research has produced a number of new analgesic drugs, many of which are capable of producing addiction. Some of these have been derived from opium and others have been produced synthetically. It is possible that many more addiction-producing drugs will be produced. A potent analgesic which is not addiction-producing has so far not been forthcoming. We have had to direct our attention to the question whether these drugs should be used with the same precautions and subjected to the same control as the morphine and heroin considered by the Rolleston Committee.

17. The second development has been in the methods of treatment of drug addiction. The withdrawal from addicts of the drug to which they are addicted has been the subject of experiment in several countries and particularly in the United States of America. These experiments have included the substitution of newer addiction-producing drugs and their subsequent gradual withdrawal, and also the use of other new drugs, such as tranquillizers, for the alleviation of the withdrawal symptoms. It has therefore been necessary to consider whether there are still circumstances in which the continued administration of dangerous drugs, even under the conditions strictly defined by the Rolleston Committee(2), can be justified.

18. We therefore had to consider:

(i) whether any new advice could be brought effectively to the notice of doctors and dentists;

(ii) whether the principles underlying the advice could be emphasised clearly to avoid misinterpretation;

(iii) whether any action was necessary to prevent the unjustifiable prescribing of dangerous drugs by some doctors;

(iv) whether there was any way of preventing the unjustified use of dangerous drugs by any doctor for himself or for members of his family ;

(v) the suggestion made in certain international organizations that Governments might set up special institutions for the treatment, care and rehabilitation of addicts on a compulsory basis.

19. In addition there has been an increase in the use by doctors and by the general public of drugs liable to cause habituation. Because they do not give rise to ill-effects substantially the same as, or analogous to, those produced by morphine or cocaine they are not within the scope of international agreements. We have considered this development.

Definitions adopted

20. From the outset we felt it necessary to have a clear and consistent idea of the phenomena confronting us. We therefore adopted the following definitions, realising that they are somewhat arbitrary and may need to be revised in the light of increasing knowledge.

Drug Addiction is a state of periodic or chronic intoxication produced by the repeated consumption of a drug (natural or synthetic); its characteristics include:

(1) an overpowering desire or need (compulsion) to continue taking the drug and to obtain it by any means,

(2) a tendency to increase the dose, though some patients may remain indefinitely on a stationary dose,

(3) a psychological and physical dependence on the effects of the drug,

(4) the appearance of a characteristic abstinence syndrome in a subject from whom the drug is withdrawn,

(5) an effect detrimental to the individual and to society.

Drug Habituation (habit) is a condition resulting from the repeated consumption of a drug. Its characteristics include:

(1) a desire (but not a compulsion) to continue taking the drug for the sense of improved well-being which it engenders,

(2) little or no tendency to increase the dose,

(3) some degree of psychological dependence on the effect of the drug, but absence of physical dependence and hence of an abstinence syndrome,

(4) detrimental effects, if any, primarily on the individual.

Sedative. A drug which depresses the central nervous system, especially at higher levels, so as to allay nervousness, anxiety, fear and excitement, but not normally to the extent of inducing sleep.

Hypnotic (or soporific). A drug used to induce sleep, which does so by depression of the central nervous system, more profoundly than a sedative but with a restricted duration of effect.

Tranquillizer (or Ataractic). A drug which promotes a sense of calmness and well-being without that degree of depression of the central nervous system commonly associated with the action of sedatives or hypnotics.

Stimulant. A drug which, by its action on the central nervous system, temporarily enhances wakefulness and alertness, improves mood and lessens the sense of fatigue.

21. In terms of physiology and pharmacology a narcotic is any agent which brings about a reversible depression of cellular metabolism and activity in the central nervous system. Substances included in any of the groups mentioned above, with the exception of the stimulants, may therefore be regarded as narcotics.

22. In more common parlance and in the proceedings of international agencies and control organisations the word "narcotic" is often limited to drugs like opium, morphine, heroin, pethidine, cocaine, etc., which are subject to measures of international control.

23. Alcohol was excluded from our considerations for the purpose of this report. We regard addiction to it as a serious problem which needs separate attention.

Extent of the problem in Great Britain

24. After careful examination of all the data put before us we are of the opinion that in Great Britain the incidence of addiction to dangerous drugs—which today comprise not only morphine and heroin but also such other substances coming within the provisions of the Dangerous Drugs Act, 1951, as pethidine, methadone, levorphanol, etc.—is still very small. The figures provided by the Home Office (see Appendix II) which might suggest an extension of addiction in Great Britain reflect, we think, an intensified activity for its detection and recognition over the post war period. At the same time the choice of drugs has altered, the new synthetics taken orally being now more popular. There is nevertheless in our opinion no cause to fear that any real increase is at present occurring. The number of doctors and nurses involved—the so-called "professional addicts"—though small in total, remains disproportionately high.

25. According to the Home Office and the police, supported by such independent evidence as we have been able to obtain, the purveying of illicit supplies of manufactured dangerous drugs for addicts in this country is so small as to be almost negligible. The cause for this seems to lie largely in social attitudes to the observance of the law in general and to the taking of dangerous drugs in particular, coupled with the systematic enforcement of the Dangerous Drugs Act, 1951 and its Regulations.

26. We would emphasise that there is, in Great Britain, no system of registration of addicts, nor any scheme by which the authorities allocate to them regular supplies of the drugs they are taking. We are, however, satisfied that the arrangements for recording manufacture and supply, and for inspection, continue to ensure that nearly all addicts ate known to the Home Office, to the Ministry of Health and to the Department of Health for Scotland.

Treatment

27. Like the Rolleston Committee, we believe that addiction should be regarded as an expression of mental disorder rather than a form of criminal behaviour.

28. We believe that every addict should be treated energetically as a medical and psychiatric problem. The evidence presented to us indicates that the satisfactory management of these cases is not possible except in suitable institutions. We are not convinced that compulsory committal to such institutions is desirable. Good results are more likely to be obtained with co-operative rather than with coerced patients. At a time when the compulsory treatment of the mentally sick is being steadily diminished we see no grounds for seeking new powers of compulsion for the treatment of drug addicts.

29. Judging by the expert advice offered to us we can see no advantage in abrupt withdrawal. Sudden and complete denial of the drug to the addict is a distressing and occasionally dangerous experience which it is best not to provoke. We do not think that we need draw up a plan of treatment, still less would we suggest that there is an ideal regimen which should be generally adopted. Yet, as this is a subject on which only a few doctors in Great Britain have any great personal experience, we have set out, in Appendix III, some notes that may serve as a guide.

Provision of institutions

30. Because the overall problem is so small it is doubtful whether there is scope for establishing specialised institutions in Great Britain exclusively for the treatment of drug addiction. We realise that at centres of this kind both medical and nursing staff would have an opportunity for training and research in the management of addicts, but very few patients would qualify for admission at any one time.

31. The best unit for the initial treatment of the established addict is, we consider, the psychiatric ward of a general hospital.

Long-term supervision and rehabilitation

32. Whereas withdrawal of the drug may be a fairly simple undertaking, long-term management, adequate rehabilitation and permanent cure present greater difficulties. Selected centres might undertake this long-term supervision and, at one or more of these, facilities for research might be provided, possibly by the Medical Research Council.

33. There remains the stage at which the addict returns to everyday life and consequently to the stresses which are liable to provoke a relapse. Social services are then required to offer all the help they can. Before the patient leaves hospital the general practitioner and, whenever appropriate, the local health authority as well, should be consulted about the provision of continued guidance and support. We recommend, too, that in every case the general practitioner should be notified immediately the patient leaves the hospital.

Prognosis

34. Information about the ultimate prognosis for drug addicts is extremely scanty and, so far as we can ascertain, the long-term results have hitherto been disappointing. This may reflect both the intractability of the condition and

the inadequacy of the treatment. Prevention, obviously, is to be preferred to cure and this leads us to acknowledge the prevailing healthy attitude of the public to this problem and the efficacy of the measures in Great Britain which keep the incidence of drug addiction to such small dimensions.

Administration of drugs to persons already addicted

35. The Rolleston Committee defined "circumstances in which morphine or heroin may be legitimately administered to addicts". These included "Persons for whom, after every effort has been made for the cure of addiction, the drug cannot be completely withdrawn, either because:

(i) Complete withdrawal produces serious symptoms which cannot be satisfactorily treated under the ordinary conditions of private(3) practice; or

(ii) The patient, while capable of leading a useful and fairly normal life so long as he takes a certain non-progressive quantity, usually small, of the drug of addiction, ceases to be able to do so when the regular allowance is withdrawn".

On the first of these points we have already stated (paragraph 28) that we believe only institutional treatment is likely to be satisfactory. With the second of these points we entirely agree, though the expression `regular allowance' has led to unfortunate and persistent misunderstanding. It has been taken in error to mean that addicts in Great Britain are entitled to receive supplies of dangerous drugs on prescription and that this involves the registration of the addict with some central authority. We think that the Rolleston Committee never meant to encourage a system of registration and from the evidence we have received it is clear that the Home Office have never acted in that belief and have never put such a system into force. The continued provision of supplies to patient addicts depends solely on the individual decision made by the medical practitioner professionally responsible for each case. We are strongly opposed to any suggestion that "registration" would be either desirable or helpful.

36. Arising also out of sub-paragraph (ii) quoted above is the conception of a "stabilised addict". The authenticity of this has been widely questioned. Many of those authorities and experienced persons who gave evidence to us nevertheless agree that this type of patient does exist. Moreover, a careful scrutiny of the histories of more than a hundred persons classsified as addicts reveals that many of them who have been taking small and regular doses for years show little evidence of tolerance and are often leading reasonably satisfactory lives. (See Appendix IV). Consequently we see no reason to reject the idea of a "stabilised addict". Indeed, to group together all "drug addicts" on the basis of a pharmacological definition may convey an over-simplified and misleading impression. There are drug addicts who have been introduced to the practice when physically healthy with drugs procured by illicit means or in the course of their professional work. This group is a very small one in Great Britain. There are those who, having been given a drug of addiction as the appropriate treatment for a painful illness, continue to be dependent on it when the original necessity for its use has disappeared. And there is a third group of those who are unable to abandon a drug rightly or wrongly prescribed for some physical or mental ailment which itself persists. Opinions may well differ as to whether those in the last group should be regarded as addicts, except in a technical sense, and where the line should be drawn between addiction to a drug and its appropriate medical use. Furthermore, we are impressed that the right of doctors in Great Britain to continue at their own professional discretion the provision of dangerous drugs to known addicts has not contributed to any increase in the total number of patients receiving regular supplies in this way.

Unjustifiable prescribing