| - |

Drug Abuse

INTRODUCTION

Illicit Drugs and Government Control

Ronald Hamowy

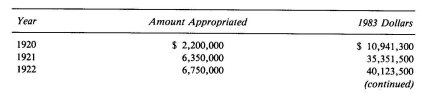

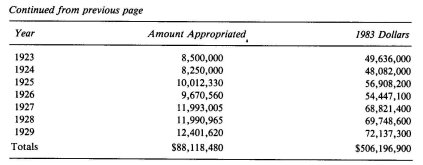

In terms of expenditures, the federal government's attempt to enforce the laws against illicit drugs constitutes the most expensive intrusion into the private lives of Americans ever undertaken in the nation's history. Even compared to the costs of enforcing Prohibition, the expenses incurred by the various federal agencies in their seemingly endless war against illicit drugs are massive. Consider the following: During the first ten years of Prohibition, between 1920 and 1929, the Congress authorized expenditures of $88.1 million for the purpose of enforcing the National Prohibition Act.' This amount translates into 506.2 million 1983 dollars. In fiscal year 1983, on the other hand, the federal government budgeted no less than $836.3 million for drug law enforcement.2 Nor does this figure include the large sums spent on prevention, treatment, and research programs, nor the costs of state and local police measures aimed at controlling the traffic in drugs. Indeed, in June 1982 President Reagan announced a new major campaign against the illegal use of drugs, which led to an escalation in the resources devoted to drug enforcement at the federal level to a minimum of $1.2 billion in 1985. One newspaper has estimated that the total amount devoted by all levels of government to the battle against the illegal consumption and distribution of drugs, together with all prevention and rehabilitation projects, is in the area of $5 billion annually.'

Yet despite these staggering costs, the availability and use of the major illicit drugs do not appear to have decreased. Although government estimates of the number of drug users are seldom the most reliable, since they are, by their very nature, subject to manipulation for political purposes,4 recent figures released by the President's Commission on Organized Crime appear consonant with other data currently available.

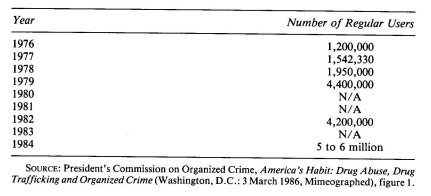

The commission, employing figures supplied by the Drug Enforcement Administration, has estimated the number of heroin users in 1981 at 490,000, about the same as was the case two years earlier.5 However, although there is no evidence to support the conclusion that this number has increased significantly in recent years, domestic heroin consumption is estimated to have increased from 3.85 metric tons in 1981 to 6.04 metric tons in 1983 and 5.97 metric tons in 1984.6 While heroin use seems to be limited to a small group, ingestion of cocaine is far more prevalent and the drug appears to have gained steadily in popularity over the past decade. The Drug Enforcement Administration calculates the number of users estimated to have employed the drug at least once per month as follows:

Although there is no clear explanation of why the number of regular users should have more than doubled between 1978 and 1979, there appears to be general agreement that approximately 5 million people currently routinely use cocaine.'

The National Narcotics Intelligence Consumers Committee (NNICC), a government interagency group, has estimated that in 1978 between 19 and 25 metric tons of cocaine were smuggled into the country and that this amount increased to between 40 and 48 metric tons in 1980, between 54 and 71 metric tons in 1983, and between 71 and 137 metric tons in 1984.8 Thus, based on the lowest NNICC estimates, the amount of illicit cocaine entering the United States has increased by 274 percent between 1978 and 1984.9

Unlike cocaine use, the consumption of marijuana appears to have decreased somewhat over the past few years, although there is no evidence whatever that this decline can be credited to more vigilant law enforcement. Estimates supplied by the Drug Enforcement Administration indicate that about 20 million people used the drug at least once per month in 1982, down from 25.5 million in 1980 and 22.7 million in 1979, but up from 16.2 million in 1977 and 14.2 million in 1976.10 Total marijuana consumption in the United States since 1982, however, seems to have remained relatively constant. The NNICC estimates consumption in 1982 at between 8,200 and 10,200 metric tons, dropping slightly to between 8,000 and 9,600 metric tons in 1983 and between 7,800 and 9,200 metric tons in 1984."

If we assume that these figures respecting heroin, cocaine, and marijuana use are accurate, at least with respect to their variation from year to year, then it is evident that the huge sums expended by the federal government in the past few years to interdict the supply of these drugs has proved a total waste of funds, even if one were sympathetic to the ends toward which they were used. Indeed, it has been shown that even if the government were to substantially improve its current levels of interdiction, the street price of these drugs would not be seriously affected. Thus, in the case of marijuana, doubling the amount of the drug seized would generate a retail price increase of no more than 12 percent, '2 and the consequent drop in supply would almost certainly prove temporary inasmuch as the marijuana plant is so easily cultivated domestically. With respect to cocaine, the effects of interdiction are even less effective. Doubling the seizure rate from its currently estimated 20 percent would raise the retail price by less than 4 percent, since the importer's selling price (approximately $50 per gram of pure cocaine "on the beach") constitutes such a small portion of the ultimate retail price (about $625 per gram)."

Having failed dramatically in its attempt to limit the available supply of illicit drugs, the Reagan administration has proposed to use the massive power of the federal government to control demand. On March 3, 1986, the President's Commission on Organized Crime, under the chairmanship of Judge Irving R. Kaufman of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, recommended that a nationwide program of drug testing be instituted, to apply to all federal employees, together with all employees working for private firms awarded government contracts. In addition, the commission urged that all private employers not otherwise covered initiate similar "appropriate" programs.14

Neither the questionable constitutionality of so intrusive a program nor its immense cost seems to have deterred its defenders on the commission. When Rodney Smith, the commission's deputy executive director and the author of the report, was confronted with its civil libertarian implications, one newspaper reported him as having "urged those 'who say it is too intrusive' to consider that Federal drug-enforcement officers are 'putting their lives on the line' because of the drug users' weekend activities.' "15

This same perverse reasoning is reflected in the supplementary comments of a group of four commission members, including Jesse A. Brewer, deputy chief of police of Los Angeles, and Eugene Meth-vin, a senior editor of Readers Digest. "Federal employees," they noted, should shun the use of illegal drugs and set an example of intolerance of those who do use or traffic in them. Brave federal officers risk their lives daily trying to stop the criminals and terrorists who run this trade. The user is a part of the trafficking.'6

Included in the category "criminals and terrorists" are no less than 25 million regular users of cocaine and marijuana, in addition to the millions more who occasionally employ these drugs. Indeed, the federal government has recently estimated that Americans are spending approximately $110 billion annually on illicit drugs and that this amount is increasing at the rate of about 10 percent per year.'7

In the fall of 1986, the Congress adopted many of the recommendations of the President's Commission and passed a $1.7 billion bill that provides for increased efforts to educate people about the harmful effects of illicit substances and to more effectively enforce the laws against their use." It is unlikely, however, that anything short of establishing a police state would prove to have significant long-term consequences either on the amount of drugs smuggled into the country or the quantity consumed.'9 This, at least, has been the traditional pattern of legislation and dealer response. Thus, Governor Nelson Rockefeller orchestrated passage of a stringent new drug law in New York in 1973, one of the more drastic provisions of which called for mandatory prison sentences of fifteen years, with a maximum sentence of life imprisonment, for all those convicted of possessing more than two ounces of heroin or who sold more than one ounce. Yet heroin use appears to have been as widespread in 1976 as before passage of the new act.2° What occurred was that dealers began employing juveniles, who were not subject to the penalties stipulated in the Rockefeller law, to engage in the riskier aspects of distribution. As a result, the juvenile division of the criminal justice system could not cope with the sheer volume of arrests for violations of the narcotics laws, with the consequence that the New York police ceased arresting juveniles for these offenses altogether.21

Yet, notwithstanding the rigidity and severity of our current drug laws and despite their having proved ineffective, serious legal reform in this area seems unlikely. As Randy Barnett has observed (Chapter 2: "Curing the Drug-Law Addiction: The Harmful Side-Effects of Legal Prohibition"), there are large numbers of people, principally employees of law enforcement agencies, who have a vested interest in seeing to it that ever increasing amounts are expended to stamp out the distribution and sale of illicit drugs. These groups are economically dependent on the existence of restrictive drug legislation; and even though the evidence might point to relaxing or repealing our current laws, their own economic benefit will be best served by supporting comprehensive legislation and a massive campaign of drug enforcement. Those whose primary concern is the enforcement of the nation's narcotics laws, together with all those who staff the institutions responsible for the treatment and rehabilitation of drug users—from administrators and physicians on down—all stand to lose if these laws were substantially liberalized; so too would the people assigned the task of instructing us concerning the evils of narcotics, and the researchers who, operating under government grants, investigate the dangerous effects of opiates, cocaine, and marijuana and who replicate experiments that have already suggested that these drugs invariably produce harmful effects on our minds and bodies.

In addition, the American government's attempts to curtail the cultivation of opium, coca, and marijuana outside the country have served far more elaborate purposes in the area of foreign policy, purposes that the government is unlikely to easily abandon. Jonathan Marshall (Chapter 4: "Drugs and United States Foreign Policy") notes that the involvement of the government in the drug war has become an extension of U.S. policy intimately linked to counterinsurgency operations and covert actions in the Third World. Profits from the international drug traffic can be truly enormous,22 and have proved a potent weapon in international politics. By tolerating the complicity of high foreign officials in the international drug traffic, American administrators engaged in foreign operations believe that the United States is contributing to the security of these regimes and providing some stability to particularly unstable regions of the world. At the same time, this policy furnishes foreign governments friendly to the United States with vast sums with which to engage in counterinsurgency operations.23

Any serious reform of the nation's drug laws is bound to meet powerful resistance from these groups within the American bureaucracy—certain officials operating in the area of foreign policy, drugn enforcement officers, administrators of drug prevention and rehabilitation facilities, and so on—who have capitalized on our current policy and who have a great deal to gain from its maintenance. And the longer this policy remains unchanged, the more entrenched those forces working for its preservation will become. Of course, American attitudes and laws relating to the use of drugs have not always had the shape they do now. David F. Musto has provided an overview of the history of legislative constraints over the sale and consumption of the major illicit drugs (Chapter 1: "The History of Legislative Control Over Opium, Cocaine, and Their Derivatives"); however, it remains worthwhile to touch briefly on several aspects of the history of social control over drugs, if for no other reason than to compare the situation as it existed a century ago with that obtaining today.

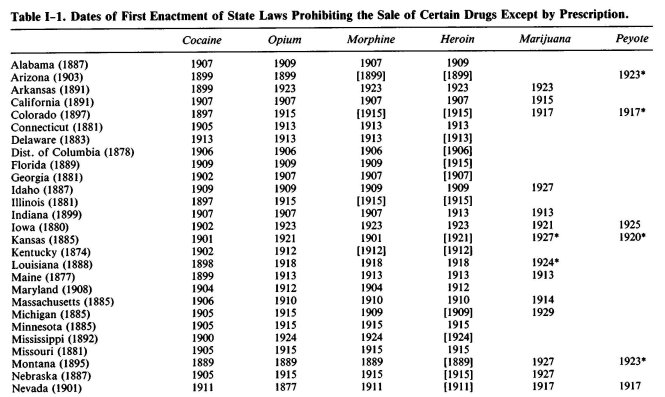

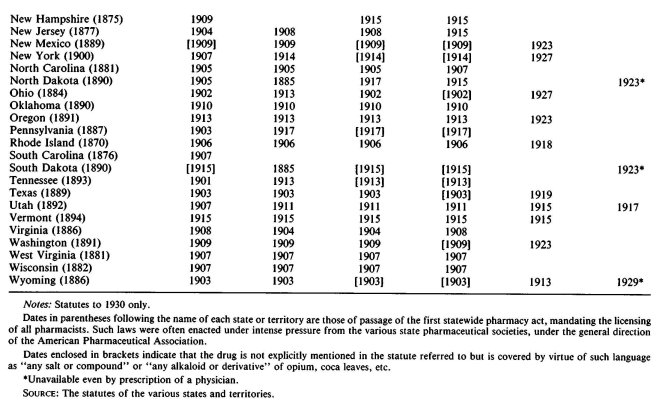

Throughout the nineteenth century there existed no laws regulating the sale of cocaine and opium and its derivatives in any of the states and territories of the Union. There were a few exceptions to this generalization in the last few years of the century—the Territory of Montana, for example, enacted legislation in 1889 that limited the sale or disposition of cocaine, opium, morphine, or any of their compounds to prescription of a physician only—but enforcement of these early statutes was sporadic, and the penalties imposed for violation were usually limited to a small fine. (Table I-1 provides a summary of the earliest state laws, to 1930, that required a physician's prescription before certain drugs could be dispensed.)

As Table I-1 indicates, there were no effective legal impediments to purchasing either cocaine or opiates throughout the country before the twentieth century. These drugs were sold over the counter by pharmacies and were also available from general stores, groceries, and through mail-order houses. A survey of Iowa during the period 1883-1885, which then had a population of less than 2 million, uncovered the fact that, besides physicians who dispensed opiates directly, no less than 3,000 stores in the state sold opiates.24 In addition, patent medicine manufacturers regularly used opiates or cocaine in their remedies. Indeed, given the limitations of the nineteenth-century physician's armamentarium, it is no wonder that so many consumers took advantage of the analgesic qualities of certain proprietary medicines that in fact contained opium or morphine. Equally effective—as tonics and for their stimulating properties—were the syrups and "wines" containing cocaine, including the most famous of these, Coca-Cola.

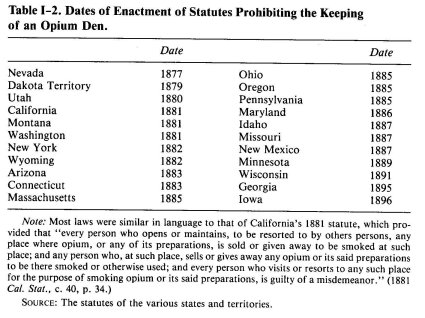

The movement to limit access to opium and its derivatives appears to have been precipitated not by a concern for the addictive properties of the drug, which physicians were aware of, but by anti-Chinese sentiment. Thousands of Chinese laborers had been imported into the United States between 1850 and 1880, primarily to help build the nation's transcontinental railroad system. Census figures show that between 1860 and 1880, the Chinese male population increased from 33,000 to over 100,000.25 Many of these workers eventually took up residence in the larger population centers of the west, while others migrated to the major eastern cities. These immigrants brought with them the custom of smoking opium in opium dens, a practice that appears to have become fashionable among certain segments of the white population as wel1.26 Concerned that opium smoking would spread to larger numbers of whites, the city of San Francisco enacted an ordinance in 1875 making it illegal, under penalty of a substantial fine, imprisonment, or both, to keep or frequent an opium den.27 San Francisco's ordinance was only the first of many such laws, most passed at the state level, aimed at stamping out the increasing popularity of opium houses. As Table 1-2 shows, twenty-two states and territories enacted legislation respecting opium dens between 1877 and 1896.

That the impetus for passage of legislation prohibiting opium dens was racist in origin there can be little doubt. The intent of physicians, legislators, and other social reformers who lobbied for these laws was to protect whites from what was commonly regarded as a loathsome Oriental vice. What Orientals themselves did was of minor concern. Indeed, Idaho's original statute of 1887, making it unlawful to maintain or frequent a house where opium was smoked, explicitly referred solely to "any white person."28 It was not until 1893 that the law was amended to apply to "any person."29 In an interesting parallel, a strong element of bigotry contributed to the criminalization of marijuana several decades later.

The statutes making opium dens unlawful, like the various later enactments by the states prohibiting the sale of cocaine, opium, or their derivatives without a physician's prescription, proved ineffective. While the larger, well-publicized smoking-houses were forced to close, smaller dens appear to have multiplied and flourished.30 Similarly, efforts to enforce the states' antinarcotics laws passed in the period before the First World War were easily nullified by a thriving interstate traffic from jurisdictions that either had not yet enacted legislation in the area or had passed comparatively weak statutes. It was partly to rectify this situation and partly to fulfill the obligations that the United States had undertaken to control the production and distribution of, among others, cocaine, opium, morphine, and heroin at the International Conference on Opium held at The Hague in 1912,3' that the Harrison Narcotic Act was passed by Congress in 1914.32

One of the chief proponents of the Harrison narcotic bill was Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, aptly described as "a man of deep prohibitionist and missionary convictions and sympathies," who regarded its passage as a moral duty owed the international community in light of America's diplomatic leadership in convening the Hague Conference." In addition, the bill had the strong support of Dr. William C. Woodward, director of the American Medical Association's Committee on Medical Legislation, and of the American Pharmaceutical Association.34 The bill, as finally enacted in December 1914, did not appear to be a prohibition statute. However, it was quickly interpreted by law enforcement officers, who were sustained by the courts, as prohibiting physicians from prescribing narcotics to any addict.35 Thus what at first seemed to be a simple record-keeping law was turned into a prohibition statute, with predictable consequences: the formation of a widespread black market in opiates and the establishment of a well-coordinated national organization devoted to smuggling and distributing drugs outside the law. 36 These effects were exacerbated in 1924, when Congress made it illegal to manufacture heroin altogether, even for medicinal purposes,37 despite the fact that morphine and heroin do not differ in any significant pharmacological respect.38 Indeed, the harm this seemingly innocuous act has done is singularly extensive, given the fact that the Harrison Act, with its numerous amendments and supplements, has served as the basic law governing narcotics in the United States for almost fifty-six years."

One of the more striking aspects of the language of the act, and those which followed it, was the inclusion of cocaine and other derivatives of the coca leaf as narcotics. These drugs cannot be regarded as "addictive" in the same sense as are the opiates, with which they were classed and from which they were seldom distinguished. Robert Byck (Chapter 6: "Cocaine, Marijuana, and the Meanings of Addiction") has observed that cocaine, like marijuana, does not have a pharmacologically significant withdrawal syndrome that would "enforce" continued ingestion of the drug. Indeed, the purely physiological withdrawal effects of cocaine are minor. Additionally, since users of cocaine do not seem to develop tolerance to the drug, they do not need ever larger doses to produce similar effects. This, of course, does not imply that cocaine is "harmless," but neither are alcohol and cigarettes, drugs that are currently legal. Why use of these drugs is permitted to remain within our individual purview, while use of cocaine or marijuana is not, is by no means obvious. Certainly there are no scientific reasons to support this position. Addiction, Dr. Byck has noted, is open to a variety of definitions, some of which can be made scientifically operational, but many of which cannot, while drug abuse is a purely relative term, subject to a host of social presuppositions that are almost never made explicit. The resulting confusion in terminology serves certain ends, specifically those of that group of people whose self-interest depends in part on the continued criminalization of these substances. These people are greatly benefited by the confusion generated when a statement about the value of certain political ends appears under the guise of a scientific observation.

There is perhaps no clearer example of this distortion than in the original campaign by the federal government to criminalize the possession and sale of marijuana without a medical prescription. Marijuana's popularity as a recreational drug in the United States emerged largely as a result of passage of the Eighteenth Amendment, which raised the price of alcohol to prohibitively high levels for many poorer drinkers, leading them to substitute use of this far less expensive weed.4° Apparently sufficient marijuana to achieve a "high" could be had for less than twenty-five cents and the drug was easily available in almost all of the larger cities, where marijuana "tea pads," similar to opium dens, were quickly established.4' Before Prohibition, marijuana use had been almost completely confined to immigrants from the West Indies and Mexico. Mexican immigration had increased substantially during the first twenty years of the century, and the number of American residents born in Mexico had reached almost half a million by 1920. By 1930, it had approached 650,000.42 Despite the growing popularity of marijuana among non-Hispanics, however, the drug remained associated with Mexicans; much of the propaganda respecting its dangers centered on its association with what was commonly viewed as an inferior ethnic group embracing alien habits, with which decent people could have little sympathy.43

During the 1920s and 1930s, marijuana was commonly linked with the worst excesses of lawless behavior. Users were reported to be oblivious to human life, shooting down even casual passers-by while engaged in spectacular holdups and other crimes." This preposterous description of the effects of marijuana use was perpetuated by none other than the Surgeon General of the United States, who issued a report in 1929 in which he observed that "those who are habitually accustomed to the use of the drug are said to develop a delirious rage after its administration during which they are temporarily, at least, irresponsible and liable to commit violent crimes." In support of this view, its author invoked, among others, "the murderous frenzy of the Malay," drunk on hashish, and the brutality of the "hashshashin," who killed without remorse on the order of their Mohammedan leaders.45 The report further concluded that marijuana was a narcotic and suggested that it was addictive and ultimately caused the habitual user to lapse into insanity.46

Although by 1930 a number of states had enacted laws prohibiting the use of marijuana without a prescription,47 there was strong pressure from a variety of sources, including local law enforcement officials and a number of congressmen, for passage of a federal statute banning the drug. This was eventually accomplished in great measure through the efforts of Harry J. Anslinger, who directed the Federal Bureau of Narcotics from its creation in 1930. With the repeal of Prohibition, Congress had transferred the antinarcotics activities of the Bureau of Prohibition to a new division of the Treasury Department, the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN), and had confirmed Anslinger as its first commissioner, a position he was to hold for thirty-two years. Anslinger had been an ardent supporter of government control over the distribution and sale of alcohol, and in 1928, as chief of the Foreign Control Section of the Prohibition Unit of the Treasury Department, he had drawn up an extensive program aimed at revitalizing enforcement of the provisions of the Volstead Act." Doubtless it was in part due to this crusading spirit that he was chosen to head the new narcotics bureau.

Anslinger's zeal to expand the operations of his new bureau, coupled with his indifference to the facts respecting the actual effects of marijuana on the behavior of its users, made the drug a natural choice with which to extend and publicize the FBN's role as the principal agency responsible for drug control in the United States. Anslinger apparently decided first to move at the state level in publicizing the menace of marijuana and in agitating for a prohibitory law. As early as 1924 a growing concern respecting the relation between the ingestion of drugs and criminal behavior had led the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws to appoint a committee to draft a uniform state narcotics act. Although several attempts had been made to draft a bill, no acceptable version emerged from the committee until 1932, some time after Commissioner Anslinger had become a participant in the drafting process. Anslinger placed the full weight and authority of the FBN behind total prohibition of the cultivation, sale, and possession of marijuana, even for medicinal purposes.49 This position was to bring the bureau into conflict with elements of the medical profession and of the pharmaceutical industry, who either opposed any reference at all to the drug in the draft law or who supported availability of the drug by prescription. The result was that the clause respecting marijuana in the final draft of the Uniform Narcotic Drug Act, as submitted to the states in 1932, was made optional and provided only that cannabis be added to the list of narcotic drugs otherwise included in the act.5° The ultimate effect of this change was to define marijuana as a narcotic, subject to all of the penalties attached to the possession and sale of narcotics, in each of the states.

In order to encourage quick passage of the act by the various states, including its provisions respecting marijuana, the FBN and Commissioner Anslinger launched a comprehensive propaganda campaign to warn the public of the horrors incident to marijuana use. At the same time, the bureau spent substantial sums of money lobbying state legislators to enact that section of the draft law dealing with marijuana. In the FBN's report for 1935, Anslinger noted: "In the absence of Federal legislation on the subject, the States and cities should rightfully assume the responsibility for providing vigorous measures for the extinction of this lethal weed, and it is therefore hoped that all public-spirited citizens will earnestly enlist in the movement urged by the Treasury Department to adjure intensified enforcement of marihuana laws."5' More typical because less restrained were Anslinger's comments on the drug made in 1937: "If the hideous monster Frankenstein came face to face with the monster Marihuana, he would drop dead of fright."52

The FBN cooperated with several organizations that shared their views on marijuana, most notably the Women's Christian Temperance Union, and with a large number of newspapers, including the Hearst chain, in inciting the public against marijuana through a series of horror stories purporting to show that the consumption of even one marijuana cigarette could lead to the most gruesome criminal acts. The following examples are typical of the approach to marijuana taken by the public press between 1932 and 1938, under the aegis of the FBN. On November 5, 1933, the Los Angeles Examiner carried the following headline above one of its feature articles: "Murder Weed Found Up and Down Coast—Deadly Marihuana Dope Plant Ready For Harvest That Means Enslavement of California Children"; and two days later, the San Francisco Examiner observed, "Dope Officials Helpless To Curb Marihuana Use."" In early 1936, Kenneth Clark, writing for the Universal News Service, syndicated a story on the dangers of marijuana that reflected the FBN's propaganda. Under the headline "Murders Due to 'Killer Drug' Marihuana Sweeping United States," Clark wrote:

Shocking crimes of violence are increasing. Murders, slaughterings, cruel mutilations, maimings, done in cold blood, as if some hideous monster was amok in the land.

Alarmed Federal and State authorities attribute much of this violence to the "killer drug."

That's what experts call marihuana. It is another name for hashish. It's a derivative of Indian hemp, a roadside weed in almost every State in the Union. . . .

Those addicted to marihuana, after an early feeling of exhilaration, soon lose all restraints, all inhibitions. They become bestial demoniacs, filled with the mad lust to kill. . . . 54

The relation between marijuana use and criminal activity had been "officially" adopted by the FBN in the mid-1930s, when Commissioner Anslinger submitted a memorandum on "The Abuse of Cannabis in the United States" to the Cannabis Subcommittee of the League of Nations Advisory Committee on Traffic in Opium and Other Dangerous Drugs in November 1934. Anslinger there observed:

Reports from narcotic officers who have consulted the police in various cities of those States in which the abuse of cannabis is most widespread, are to the effect that marihuana addicts are becoming one of the major police problems. While it is admitted by these officers that marihuana offenses do not show up directly in many cases, they state their estimate to be that fifty percent of the violent crimes committed in districts occupied by Mexicans, Turks, Filipinos, Greeks, Spaniards, Latin-Americans and Negroes, may be traced to the abuse of marihuana.

A prosecuting attorney in Louisiana states that the underworld has been quick to realize the possibility of using this drug to subjugate the will of human derelicts. It can be used to sweep away all restraint and many present day crimes have been attributed to its influence.

Police officials in the South have found that, immediately before undertaking a crime, the criminal will indulge in a few marihuana cigarettes in order to remove any natural sense of restraint which might deter him from committing the contemplated acts and in order to give him the false courage necessary to his purpose.55

There is good evidence that Anslinger himself did not believe such arrant nonsense concerning the effects of marijuana. Several scientific studies, all of them familiar to the FBN, indicated, in the words of the Indian Hemp Drug Commission Report of 1893-94, that "the moderate use of hemp drugs is practically attended by no evil results at all." The commission also concluded that "moderate use. . . produces no injurious effects on the mind" and results in "no moral injury whatever."56 Similar findings were reached by the Panama Canal Zone Study of 1925, which was charged with investigating marijuana use among American troops stationed on the Isthmus. Despite the concern of the military authorities that increasing use of the drug could well pose a threat to discipline, the members of the committee, including its military advisers, found that "there is no evidence that marihuana . . . is a 'habit-forming' drug in the sense in which the term is applied to alcohol, opium, cocaine, etc., or that it has any appreciably deleterious influence on the individuals using it," and recommended that "no steps be taken by the Canal Zone authorities to prevent the sale or use of marihuana."57

There seems little doubt that Anslinger chose to neglect what scientific evidence existed concerning the consequences of marijuana use for purely political purposes. In the event, he proved successful in his campaign to gain passage of the Uniform Narcotic Drug Act by the various states. Between 1933 and 1937, forty states had enacted the statute and in twenty-nine of these the state legislatures had included the optional provision respecting marijuana, which the FBN had so strongly supported. By 1937, Tennessee and South Carolina remained as the only two jurisdictions in the United States without laws against marijuana.

Having succeeded in the first stage of his crusade, Anslinger next turned his attention to agitating for enactment of a federal law governing the drug.58 The publicity mounted by the FBN against marijuana during the previous several years now served to advance support for federal controls. Indeed, Anslinger's accounts of the connection between marijuana and violent crime became even more intemperate when, in 1937, the Treasury Department submitted to Congress the draft of a bill that was to become the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937. Perhaps the most famous of Anslinger's numerous horror stories concerned a young man named Victor Licata, who was reputed to have gone berserk and hacked his family to pieces while under the influence of a marijuana cigarette. In an article published in collaboration with Courtney Ryley Cooper in 1937, Anslinger recounted the particulars of the case:

An entire family was murdered by a youthful addict in Florida. When officers arrived at the home, they found the youth staggering about in a human slaughterhouse. With an ax he had killed his father, mother, two brothers, and a sister. He seemed to be in a daze. . . . He had no recollection of having committed the multiple crime. The officers knew him ordinarily as a sane, rather quiet young man; now he was pitifully crazed. They sought the reason. The boy said he had been in the habit of smoking something which youthful friends called "muggles," a childish name for marihuana.59

Anslinger's testimony before the House Ways and Means Committee and a subcommittee of the Senate Finance Committee was filled with such spectacular reports of users driven mad by even the most casual contact with the drug. Thus, during the one day of Senate hearings on the bill, Anslinger, whose knowledge of pharmacology was about as extensive as his mastery of early Byzantine architecture, offered the following analysis of the effects of marijuana in reply to a question regarding what dosage was thought to be dangerous.

I believe in some cases one cigarette might develop a homicidal mania, probably to kill his brother. It depends on the physical characteristics of the individual. Every individual reacts differently to the drug. It stimulates some and others it depresses. It is impossible to say just what the action of the drug will be on a given individual, or the amount. Probably some people could smoke five before it would take effect, but all the experts agree that the continued use leads to insanity. There are many cases of insanity.'

Despite the perfunctory nature of these hearings, the bill passed both the House and the Senate with practically no debate and was signed into law on August 2, 1937. The Marihuana Tax Act6' was nominally a revenue-producing act that imposed a tax on, among others, physicians who prescribed, and pharmacists who dispensed, the drug. Only the nonmedical possession and sale of marijuana was made criminal by the statute, while all persons engaged in the legal chain of cultivation and sale for medicinal purposes—growers, manufacturers, druggists, doctors, etc.—had to comply with the extensive record-keeping provisions of the act and to pay an annual license fee. The law, however, effectively called a halt to continued use of the drug as a medicinal agent.

Not content with the dampening effects the Marihuana Tax Act alone was to have on the medical uses of the drug, Anslinger immediately began to mobilize support within the medical profession itself to eliminate marijuana from the physician's armamentarium. In 1941, Anslinger was successful in convincing Dr. Ernest Fullerton Cook, chairman of the Commission on Revision of the United States Pharmacopeia, to remove cannabis from the USP. The results of this action followed quickly; marijuana was no longer prescribed as a medicinal agent, and research on possible medical uses of the drug came to an abrupt halt. It is impossible to assess the damage caused by marijuana's removal from the USP. It is also difficult to understand why Anslinger should have displayed such mean-spiritedness in attempting to stamp out the drug even when employed for medical purposes. We do know that the legacy of his campaign to criminalize a drug as comparatively harmless as marijuana at both the state and federal levels62 was the humiliation and suffering of hundreds of thousands of people who were to endure the indignity of arrest and, in many cases, imprisonment. Equally important, the medical advances that might have been made through more extensive research into the possible beneficial effects of cannabis have been denied us for almost half a century.

As Drs. Lester Grinspoon and James Bakalar observe (Chapter 5: "Medical Uses of Illicit Drugs"), the official representative of the American Medical Association at the congressional hearings on marijuana in 1937 had taken strong exception to the language of the bill on the ground that cannabis might prove to have substantial medical benefits.63 Indeed, that legal difficulties prevented further research on the drug is just one more regrettable aspect of its criminalization. Among the recent studies to which Grinspoon and Bakalar call our attention are those that suggest that marijuana is useful in the treatment of alcohol dependence and that, under certain conditions, it can act as an efficacious analgesic and as an anticonvulsant. In addition, the authors report that cannabis appears to be of value in treating glaucoma and as an antiemetic. They point to the significant fact that the legal problems connected with research on the effects of marijuana, as with narcotics and other controlled substances, cannot but discourage such studies; further, official attitudes toward the recreational use of illicit drugs commonly spill over into a biased perception of the medical potential of these substances.

There is a further problem, which we would do well to underscore, respecting research on the effects of controlled substances. More and more scientific research is funded through agencies either directly or indirectly answerable to various levels of government, particularly the federal government.64 Before a scientific hypothesis becomes scientific fact, it must first have undergone empirical investigation and rigid testing, and in the ordinary course of research, this testing must have been replicated with similar results. Now, it is clearly going to prove more difficult to receive a grant to replicate an experiment the conclusions of which defy the prevailing orthodoxy than to procure funds for projects that conform to current scientific doctrine. It follows that the increasing concentration of research funds in the hands of government or quasi-government agencies will serve to reinforce the official prejudice that controlled substances are dangerous even when ingested in moderate amounts and, for the most part, are of limited medical value.

There is something especially distressing in fact that scientific research should be colored by the legal treatment accorded certain drugs, particularly when we recall the history of the various prohibitory laws to which the opiates, cocaine, and marijuana are now subject. It is surely more than a curiosity that the original motive impelling state legislatures to control the use of opium was to be found in anti-Chinese sentiment and that the early history of agitation for legislation prohibiting the use of marijuana was associated with anti-Mexican attitudes. Similarly, laws governing the sale and possession of cocaine can, in part, be explained by the notion popular at the beginning of the century that the use of the drug was intimately connected with the bestial rage of blacks involved in crimes of violence.65 From their origins in an ignorant racism, the various statutes governing opiates, cocaine, and marijuana have become an unquestioned part of American law. That this approach to the use of these substances might be not only ineffective but actually destructive is seldom considered. Yet, the smugness long shown by the drug enforcement bureaucracy has begun to fade as the figures indicate that our drug laws, despite the huge amounts expended in enforcing them, have done nothing to decrease drug use. Indeed, as Arnold Trebach has reported (Chapter 3: "The Need for Reform of International Narcotics Laws"), the evidence points to the fact that the United States is not alone in this regard but is in the vanguard of a worldwide escalation in illicit drug use.

Trebach has mustered a substantial amount of impressionistic data showing that opiate use has increased substantially in both Europe and the Orient in the past twenty-five years,66 to the point where even the most draconian penalties have not been able to deter an increase in illicit consumption.° One of the more worrisome features of this situation, Trebach notes, is the response of many foreign governments, which have followed the United States in attempting to deal with drug use through the enactment of prohibitory laws with harsh punishments. Such laws, besides being inhumane, have proved incapable of deterring drug use while encouraging the creation of a complex illegal system of supply. In light of this, some reform in the structure of drug legislation is essential. Although Trebach stops short of recommending the total decriminalization of illicit drugs, he does support a program along the lines that prevailed in Great Britain prior to 1968, whereby regular opiate users were able to maintain their habit through the mediation of a physician.68 Whether or not one is sympathetic to this specific program, there is little question that reform of our current drug laws is imperative if billions of dollars more are not to be wasted and if more lives are not to be ruined by such legislation.

It we were in fact to remove all prohibitory laws respecting illicit drugs, is there some way of determining the most likely number of users? Robert Michaels (Chapter 8: "The Market for Heroin Before and After Legalization") has undertaken to answer this question with respect to heroin. As Michaels points out, any reasonable attempt to predict how many users there would be if heroin were decriminalized is predicated on the existence of more or less reliable data on the current user population. These data, however, simply are not available. The government, which provides such statistics, has consistently manipulated the figures it publishes for one political purpose or another, fully aware of the fact that such data on the number and characteristics of users are essential if researchers are to realistically extrapolate to conditions in which heroin is legal. As Michaels observes, there exist organized interests outside of government that are concerned with accurate demographic statistics in other areas, and these interests will pressure the government to collect and provide reliable figures if this is not being done. However, no such pressure group exists for unambiguous and precise data respecting heroin users.

Even the term addict is subject to immense variation, depending on when the term is used, the purpose for which it is being used, and the agency using it. When a new "war on drugs" is declared, or when the government agencies charged with enforcement of the drug laws are seeking larger appropriations, the number of addicts tends to rise sharply. Not all heroin users, of course, are "addicts," in the sense that they exhibit the classic symptoms of physical withdrawal. Indeed, the overwhelming majority are only occasional users, known as "chippers." Nor is addiction inevitable after prolonged use. (The Drug Enforcement Administration's claim that anyone having used heroin more than six times becomes addicted to the drug69 is contravened by all the scientific evidence.) In addition, large numbers of heroin addicts apparently go through voluntary withdrawal and many, after having been briefly addicted, give up heroin permanently.7° All these factors contribute to imprecision in the use of the term, an imprecision reflected in the fact that the number of current "addicts" in the United States has been variously estimated as 69,000 (Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, 1969) to 740,000 (Drug Enforcement Administration, 1977).

Attempts to determine the number of addicts immediately after passage of the Harrison Narcotic Act in 1914 seem to have varied almost as widely as do current estimates. In 1917, it was claimed that there were 300,000 addicts in New York City alone,7' and in 1924 one physician calculated that more than 1,000,000 people throughout the country were addicted to opiates.72 Perhaps the most reliable figures, however, were those offered by Dr. Lawrence Kolb of the U.S. Public Health Service, who carefully analyzed all available data pertinent to the subject in 1924 and who concluded that the addict population at that time was between 110,000 and 150,000, and had never been higher than 264,000 when, after 1900, the number of addicts steadily decreased.73

In the absence of any more reliable data, it does not appear likely that, under decriminalization, the number of heroin addicts—as opposed to occasional users, whose normal living patterns would remain essentially unchanged—would exceed the current "best estimate" of 500,000. More important, there is evidence to suggest that a clear positive correlation exists between heroin use and certain crimes, particularly robberies, burglaries, and thefts. Indeed, a recent study has concluded that daily heroin users commit twice as many robberies and burglaries as those sentenced to California prisons for such crimes." The authors conclude that "on an annual basis, the average heroin abuser probably committed about twenty-five crimes (robbery, burglary, and larceny) against individual victims who would complain to police. But he also committed an additional seventy-five nondrug crimes without clear victims (mainly shoplifting for resale, burglaries of abandoned buildings, and larcenies considered as losses by victims)."75 These conclusions are consistent with earlier studies, including an analysis of the effects of the price of heroin on crime-rates in Detroit.76 Researchers there found that a 10 percent increase in the street price of heroin consistently led to a rise of 2.9 percent in reports of revenue-raising crimes, particularly those crimes associated with heroin use, armed and unarmed robberies and burglaries of residences.77 Whether a substantial portion of the crimes engaged in by heroin-users is committed for the purpose of raising revenue in order to buy the drug, or whether users would commit these crimes regardless of their drug-use, can never be proved conclusively, but the data strongly suggest the former. If such a correlation does indeed exist, as is commonly assumed, then one immediate effect of the legalization of the opiates would be a reduction in certain crimes that most people find particularly oppressive since, as Michaels reports, twenty 10-milligram tablets of legally produced heroin cost approximately $1.00, while the average heroin habit is limited to about 50 milligrams per day.

Estimates of the number of addicts and the crime-rates that would follow decriminalization are not the only issues that deserve serious consideration in any discussion of the legalization of illicit drugs. Dr. Norman E. Zinberg (Chapter 7: "The Use and Misuse of Intoxicants: Factors in the Development of Controlled Use") makes the important point that the use of illicit drugs, like all substance gratification, is a function of a variety of factors beyond the simple desire to enjoy the substance. More particularly, how, when, where, and how much of the substance we use is in part determined by the social sanctions and rituals that surround the substance's use. An especially unfortunate aspect of our current drug laws, which have now been in place for half a century or more, is that our culture has been deprived of the natural means by which we would ordinarily accommodate and adapt ourselves to drug use, in the way most of us have accommodated and adapted ourselves to the socially acceptable use of alcohol. Zinberg rightly characterizes our current policy toward drug use as naive, since it assumes that all use is misuse, that is, uncontrolled use. Thus, any policy that apparently reduces the total amount of current use is advertised as a victory in the war on drugs. What is lacking in this simplistic analysis is an awareness that only a percentage, possibly a fairly modest percentage, of use is uncontrolled and therefore warrants legal sanctions in the eyes of many. There is a certain fanciful quality to the rationale of most government action (and in far too many discussions) concerning illicit drugs, that only two possibilities exist, either total abstinence enforced by the police power of the state or uncontrolled use leading to addiction. Drug enforcement agencies have done everything in their power to promote this notion and the media, taking their cue from the government, have bombarded us with this view of drug use. In fact, as Zinberg makes clear, the great bulk of such use falls somewhere between these two extremes and is governed by a series of informal controls that have arisen despite the presence of prohibitory laws.

Implicit in Zinberg's analysis is the view that social arrangements of more than passing value are, at their inception, fragile and require time to take on the status of convention. The laws respecting drugs under which we operate, however, have acted as serious obstacles to the development of more systematic rules of behavior respecting drug use which arise independent of government command. These laws are predicated on the theory that complex social structures are, of necessity, the product of conscious design (that is, can only come about through the action of the legislature). It has become increasingly apparent over the past century, however, that the actions of government are no substitute for the more complex knowledge embedded in the customs and social arrangements that arise independent of deliberate planning. It is absurd to suppose that men obey rules only when the punishment for breaking them involves legal sanctions. The overwhelming majority of us accommodate our behavior to a host of social conventions without the need for police enforcement, and there is every reason to believe that we would adjust our actions to conform to acceptable social practice with respect to drug use, were we permitted to.

In light of the total failure of our current policy toward illicit drugs, it seems clear that earnest consideration must be given to cornplete abandonment of all prohibitory laws. Both prudential reasons and principle dictate that the decriminalization of marijuana, cocaine, and the opiates would halt the current massive drain of public funds and the substantial suffering brought about through attempts to enforce these unenforceable laws. Evidence indicates that legalization would do much to reduce the current crime-rate and thus contribute to restoring the safety of our city streets. It would reduce the amount of government corruption, which is partly a function of the immense fortunes that are constantly made in the drug trade, and it would play a large part in decreasing the profits that flow to organized crime. All these arguments have recently been offered by a host of writers calling for repeal of our drug laws.78 Of far greater importance, however, is the fact that any statute aimed at preventing behavior that does harm to no one but the actor—that is, legislation that creates victimless crimes—raises significant ethical questions in a society the most important of whose founding principles is individual freedom.79 The argument that the ingestion of drugs is in reality a crime with many victims since it harms the family and community of the drug-user, who are denied his productive capabilities and his forgone earnings, as well as the drug-user himself, who is deprived of his rationality and his health, has no more merit than similar arguments applied to wastrels, layabouts, and chronic overeaters.80 Drug use is a victimless crime and defenders of criminalization cannot avoid the problem of how to reconcile these laws with a society based on personal liberty and individual responsibility.8'

The importance of the moral dimension of our drug laws makes it particularly fitting that the last essay in this volume deals with the ethical aspects of drug control in a free society. Dr. Thomas Szasz (Chapter 9: "The Morality of Drug Controls") has written passionately in defense of the notion that the freedom to eat and drink what we choose can be no less a basic right in a society dedicated to individual liberty than the freedom to speak and to worship as our consciences dictate. It is an unfortunate commentary on how far this nation has strayed from its political foundations that some writers have regarded the most appropriate way of describing the relation between the individual and government as comparable to the relation of a public ward to a benign magistrate.82 If we were to accept this metaphor as an accurate description of the essential nature of political life then, of course, we can offer no principled objections to laws prohibiting drug use. It is uncertain, however, how many people would embrace this view of the nature of American society if they were fully aware of all its implications. This country was not founded on the principle that our governors are our parents, to whom we have entrusted the power to prevent us from harming ourselves. Nor is our legal system predicated on the notion that we are not responsible for our own actions. To accept this view is to accept that the ideal state is a beneficent totalitarianism, staffed by an endless number of well-meaning, albeit intrusive, bureaucrats.

The genius of American society since its founding has consisted in its openness and its divefsity. We have embraced a multiplicity of values and customs, and have grown stronger for it. Drug laws, of which Prohibition was simply the most spectacular example, strike at the very root of our pluralistic society and constitute a surrender of our traditional toleration for disparate values. The analogy with religion that Szasz invokes is a particularly apt one. For centuries it had been thought that a common religion comprised the cement that held society together and that its absence would lead to social and political chaos. Yet religious toleration has in fact strengthened society, not weakened it. There is every reason to believe that the effect would prove no different were we to tolerate those groups who wish to ingest drugs other than those we currently find socially acceptable.

A truly liberal society, without violating the principles under which it operates, cannot concern itself with preventing some people from using certain drugs because a segment of the community condemns such pleasures any more than it can prohibit some of us from reading certain books because some portion of the population finds these works offensive. We may choose to eliminate what we consider to be vice and depravity through exhortation and discussion, or we may opt to root out sin by using the police power of the state. It is only the first method, however, that is compatible with a society of free people who have the courage to take responsibility for their own actions.

1. Charles Merz, The Dry Decade, originally published in 1930 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1969), p. 329. The figures for each year (exclusive of those amounts allocated for enforcement of the Harrison Narcotic Act), with their 1983 values as adjusted by the Consumer Price Index, are as follows:

2. The amount originally allocated for fiscal 1983 was $702.8 million. See Federal Strategy for Prevention of Drug Abuse and Drug Trafficking, 1982 (Washington, D.C.: Drug Abuse Policy Office, 1982), P. 74. Following President Reagan's "declaration of war" on drugs, the Congress increased its funding for drug enforcement by $127.5 million, plus an additional $6 million to cover the costs of the newly established South Florida Task Force. See Steven Wisotsky, "Exposing the War on Cocaine: The Futility and Destructiveness of Prohibition," Wisconsin Law Review (1983): 1307, n. 10.

3. "Society Pays Price for Drug Haunting America," Washington Times, 25 September 1984. The drug legislation passed in 1986 has, of couse, added a minimum of a half-billion dollars to that sum.

4. For a particularly dramatic instance of political exploitation of the available data on drug users, see Edward Jay Epstein, Agency of Fear: Opiates and Political Power in America (New York: Putnam, 1977), pp. 173-77, and Charles E. Silberman, Criminal Violence, Criminal Justice (New York: Random House, 1978), pp. 174-76.

5. President's Commission on Organized Crime, America's Habit: Drug Abuse, Drug Trafficking and Organized Crime (Washington, D.C.: 3 March 1986, Mimeographed), figure 5. There is an inexplicable drop in the estimates supplied by the Drug Enforcement Administration, from 740,000 in 1977 to 467,000 in 1979 and 465,000 in 1980.

6. Ibid., figure 6.

7. The rise in popularity of cocaine in the late 1960s appears to have been accompanied by a shift in the method by which the drug has been most commonly ingested. While intravenous injection had been the customary mode of ingesting cocaine before its reappearance some twenty years ago, snorting is currently the preferred means. This method prevents large amounts of the drug from being taken in quickly. See James Lieber, "Coping with Cocaine," The Atlantic Monthly 257 (January 1986): 42.

8. President's Commission on Organized Crime, America's Habit, figure 4.

9. If one were to use the higher estimates supplied by the NNICC, the amount of cocaine smuggled into the country in 1984 would have reached 548 percent of its 1978 levels.

10. President's Commission on Organized Crime, America's Habit, figure 10. In 1982 approximately 11.5 percent of teenagers 12 to 17 years old and 27 percent of young adults 18 to 25 years old used marijuana at least once per month (ibid., p. 34).

11. Ibid., figure 11.

12. J. Michael Polich et al., Strategies for Controlling Adolescent Drug Use, R-3076-CHF (Santa Monica, Calif.: Rand Corporation, 1984), p. x.

13. Ibid. The actual street price of a gram of cocaine is usually considerably less than $625, since the drug sold at the retail level is commonly heavily adulterated.

14. President's Commission on Organized Crime, America's Habit, recommendations 3 and 8 in section entitled "Reducing the Demand for Drugs."

15. "U.S. Panel Urges Testing Workers for Use of Drugs," New York Times, 4 March 1986, p. 14. The general argument, of course, is that the government may institute any measure, no matter how oppressive, if its aim is the enforcement of a law that has proved dangerous to law-enforcement officers. The same rationale could be used to support more stringent apartheid legislation or any measure calling for preventive detention.

16. President's Commission on Organized Crime, "Supplemental Views of Commissioners Brewer, Manuel, Methvin, and Rowan," The Impact: Organized Crime Today (Washington, D.C.: April 1986, Mimeographed), p. 179 (italics in the original).

17. "Meese's Ambitious War Against U.S. Drug Abuse Is Faltering as Cocaine Use Continues to Spread," Wall Street Journal, 9 January 1986, p. 44.

18. The New York Times reported that the commission recommended that the "Defense Department, now involved in helping civilian drug-enforcement agencies in a limited way, should recognize that drug-traffickers constitute a 'hostile threat' to the United States and the military should expand its role in drug law-enforcement" (4 May 1986, p. 14). With respect to the legislation passed in the fall of 1986, however, a proposal to employ military forces alongside civilian drug agencies for purposes of domestic enforcement was dropped from the final bill. There is some question that the use of the military for this purpose violates the provisions of the Posse Comitatus Act [18 U.S.C.§1385 (1982)1, which forbids employing the armed forces to enforce civil law.

19. With respect to heroin, one authority has concluded that changes in law enforcement do contribute to determining which potential customers have access to the drug and which do not. See John Kaplan, The Hardest Drug: Heroin and Public Policy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983), p. 78.

20. In addition, the 1976 study of the effects of the Rockefeller law, commissioned by the Association of the Bar of the City of New York, found "no evidence of a sustained reduction in heroin use after 1973" and noted that "the pattern of stable heroin use in New York City between 1973 and mid-1976 was not appreciably different from the average pattern in other East Coast cities." See Joint Committee on New York Drug Law Evaluation, The Nation's Toughest Drug Law: Evaluating the New York Experience (New York: Association of the Bar of the City of New York; Drug Abuse Council, 1977). p. 3.

21. See Kaplan, The Hardest Drug, p. 79.

22. The most widely quoted estimate of the income accruing to organized crime from narcotics is that of James Cook, who in 1980 estimated this amount at $63 billion annually. See Sima Fishman, Kathleen Rodenrys, and George Schink, "The Income of Organized Crime" prepared for the President's Commission on Organized Crime (Philadelphia: Warton Econometric Forecasting Associates, 6 March 1986, Mimeographed), p. 25. Those involved in drug trade outside the country are reputed to have amassed various fortunes. According to one report, Gonzalo Rodriguez, one of Colombia's top drug traffickers, collects about $20 million per month from drug operations, while Roberto Suarez Gomez is estimated to earn $33 million per month from the production of coca leaves in Bolivia. See Laurence Gonzales, "Why Drug Enforcement Doesn't Work," Playboy 32 (December 1985): 104.

23. In April 1985, Mark Kleiman, writing in the Wall Street Journal, observed: "Governments, their agencies, their employees and their foreign surrogates are rather frequently involved in drug dealing because it is a way to make quick, substantial and untraceable money; they often need or want money they don't have to account for; they have powers, resources, immunities and organizational capabilities that give them advantages in some aspects of drug dealing, and these make them more competitive in moving narcotics than they are in making steel or automobiles." (See "We Can't Stop Friend or Foe in the Drug Trade," Wall Street Journal, 9 April 1985).

On May 29, 1986, two American journalists filed a federal lawsuit in Miami, Florida, which accused "a group of Americans and Nicaraguan guerrillas [Contras] of smuggling cocaine to finance military operations against the Nicaraguan government." The suit charged that several of the thirty defendants, resident in Florida, employed seafood importing firms as fronts for the purpose of smuggling cocaine into the United States to finance Contra operations. It need hardly be added that the State Department immediately denied all charges. See Reuter's dispatch, "Cocaine dealing finances contras, two reporters say," Globe and Mail (Toronto), 30 May 1986, p. A5.

24. Edward M. Brecher, Licit and Illicit Drugs (Boston: Little, Brown, 1972), p. 3.

25. Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1970, 2 vols. (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1975), Vol. 2, P. 14 (Series A 91-104). During the same period, the Chinese female population grew from 1,800 to 4,800!

26. One contemporary account notes that "men and women, young girls—virtuous or just commencing a downward career—hardened prostitutes, representatives of the 'hoodlum' element, young clerks and errand-boys who could ill afford the waste of time and money, and young men who had no work to do, were to be found smoking together in the back rooms of laundries in the low, pestilential dens of Chinatown, reeking with filth and overrun with vermin, in the cellars of drinking saloons, and in houses of prostitution." See H. H. Kane, Opium-Smoking in America and China (New York: Putnam, 1882; facsimile edition: New York: Arno Press, 1976), p. 2.

27. Ibid., p. 1. A similar law was passed in Virginia City, Nevada, in 1876 (ibid., p. 3).

28. 10 February 1887; Rev. Stat. 1887,§ 6830.

29. 1893 Idaho Sess. Laws 22.

30. Kane, Opium-Smoking in America and China, p. 2.

31. The full text of the International Opium Convention, which was signed at The Hague on 23 January 1912, appears as Appendix I to Charles E. Terry and Mildred Peliens, The Opium Problem (New York: American Social Health Association, 1928; facsimile edition: Montclair, N.J.: Patterson Smith, 1970), pp. 929ff.

32. Public Law No. 233, 63rd Congress, 17 December 1914 [38 Stat. 785 (1914)]. Earlier the same year, Congress enacted a statute imposing a prohibitively high tax ($300 per pound) on opium prepared for smoking within the United States. See Public Law No. 47, 63rd Congress, 17 January 1914 [38 Stat. 277 (1914)]. Since the Congress had earlier banned the importation of all smoking opium [Public Law No. 221, 60th Congress, 9 February 1909 [35 Stat. 614 (1909)], the effect of this additional legislation was to close off all supplies of smoking opium within the country.

33. Brecher, Licit and Illicit Drugs, pp. 48-49.

34. David F. Musto, The American Disease: Origins of Narcotic Control (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1973), pp. 55-56.

35. Dr. Hamilton Wright, who was later given the title "the father of American narcotic laws" and who served as the United States representative at the Shanghai Opium Convention of 1909 and the International Conference on Opium held at The Hague in 1912, had hoped that the Harrison Act would be interpreted precisely in this manner. Wright believed that "since the statute was the outcome of an international agreement, . . . it could employ police powers within a state in addition to the traditional powers associated with a federal revenue measure. This would give great importance to the words 'prescribed in good faith,' enabling the federal government to argue, as it did, that this phrase prevented addiction maintenance. Without some legal sanction for federal police powers in the states, the Act would be limited to record keeping. Wright based his optimistic expectation on the principle that a treaty to which the United States had become a signatory and which had been ratified by the Senate, would take precedence over state law" (ibid., p. 62). In the event, the Supreme Court did not regard this broad interpretation of the Harrison Act as requiring the existence of a prior treaty. A summary of the major court decisions sustaining the constitutionality of the Harrison Act and the government's argument that "mere addiction" did not constitute a disease that warranted treatment "in good faith" appears in Terry and Peliens, The Opium Problem, pp. 758-61, and in Arnold S. Trebach, The Heroin Solution (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982), pp. 125-31. See especially the excellent study by Alfred R. Lindesmith, The Addict and the Law (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1965). Among the more important cases are United States v. Doremus 249 U.S. 86 (1919) (upholding the constitutionality of the Harrison Act); Webb v. United States 249 U.S. 96 (1919) (holding that it was a violation of the act to prescribe to addicts); fin Fuey Moy v. United States 254 U.S. 189 (1920) (addictive maintenance a contravention of the statute); and, United States v. Behrman 258 U.S. 280 (1922) (the amount of narcotic prescribed may itself determine "prescribing in bad faith").

36. Brecher, Licit and Illicit Drugs, p. 51.

37. Public Law No. 274, 68th Congress, 7 June 1924 [43 Stat. 657 (1924)1.

38. President's Committee on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice, Task Force Report: Narcotics and Drug Abuse (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1967), p. 3. Dr. Lawrence Kolb noted as early as 1925 that "if there is any difference in the deteriorating effects of morphine and heroin on addicts, it is too slight to be determined clinically." See "Pleasure and Deterioration from Narcotic Addiction," Mental Hygiene 9 (1925): 724; quoted in Brecher, Licit and Illicit Drugs, p. 51).

39. In 1970 the federal government consolidated the pertinent provisions of its various previous statutes dealing with narcotics into the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act (Public Law No. 513, 91st Congress, 27 October 1970 [84 Stat. 1236]).

40. Brecher, Licit and Illicit Drugs, p. 410.

41. Mayor's Committee on Marihuana (1944) (LaGuardia Report), "The Marihuana Problem in the City of New York," in David Solomon, ed., The Marihuana Papers (New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1966), p. 246.

42. Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics, vol. 1, p. 117 (Series C 228-295). In 1900, the Mexican-born population was less than 104,000.

43. See Jerome L. Himmelstein, The Strange Career of Marihuana: Politics and Ideology of Drug Control in America (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1983), pp. 50-54.

44. Brecher, Licit and Illicit Drugs, p. 411. Even a periodical as respected as Scientific American referred to marijuana as "more dangerous than cocaine or heroin" ("Marihuana More Dangerous than Heroin or Cocaine," Scientific American, May 1938, p. 293. A good summary of the hysteria surrounding the use of marijuana that prevailed before passage of the federal Marihuana Tax Act of 1937 appears in Richard J. Bonnie and Charles H. Whitebread 11, The Marihuana Conviction: A History of Marihuana Prohibition in the United States (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1974), pp. 92-153.

45. Hugo S. Cummings, Surgeon General, Preliminary Report on Indian Hemp and Peyote (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1929), quoted in Bonnie and White-bread, The Marihuana Conviction, p. 128.

46. Ibid., p. 60.

47. See table I-1 and map 1 in ibid., p. 52. Of the twenty-four jurisdictions passing prohibitory statutes before 1930, there is a discrepancy in the dates of enactment of four states, which appear to have passed legislation limiting the sale of marijuana before the dates indicated by Bonnie and Whitebread.

48. Musto, The American Disease, p.211

49. Bonnie and Whitebread, The Marihuana Conviction, p. 83.

50. Ibid., pp. 84-91.

51. Bureau of Narcotics, U.S. Treasury Department, Traffic in Opium and Other Dangerous Drugs for the Year Ended December 31, 1935 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1936), p. 30. See also Anslinger's comments made in a radio broadcast in early 1936: "Another urgent reason for the early enactment of the Uniform State Narcotic Act is to be found in the fact that it is THE ONLY UNIFORM LEGISLATION yet devised to deal effectively with MARIHUANA. . . .

"There is no Federal law against the production and use of Marihuana in this country. The legal fight against its abuse is largely a problem of state and municipal legislation and law enforcement.

"All public spirited citizens should enlist in the campaign to demand and to get adequate state laws and efficient state enforcement on Marihuana." ("The Need for Narcotic Education," speech over NBC, 24 February 1936; quoted in Bonnie and Whitebread, The Marihuana Conviction, p. 98.)

52. Washington Herald, 12 April 1937; quoted in Bonnie and Whitebread, The Marihuana Conviction, p. 117.

53. Quoted in Larry Sloman, Reefer Madness: The History of Marijuana in America (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1979), p. 44.

54. Quoted in ibid., p. 48. See also Himmelstein, The Strange Career of Marihuana, pp. 54-68, which contains a synopsis of the popular literature of the period on the subject.

55. League of Nations, Advisory Committee on Traffic in Opium and Other Dangerous Drugs, The Abuse of Cannabis in the United States (Addendum) P.C. 1542 (L)], 10 November 1934, (Memorandum forwarded by the representative of the United States of America); quoted in Bonnie and Whitebread, The Marihuana Conviction, pp. 146-147.

56. Marijuana: Report of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission, 1893-1894 (Silver Spring, Md.: Thomas Jefferson Co., 1969), p. 263; quoted in ibid., pp. 130-31. The commission was convened to investigate the effects of cannabis use on the native population of India.

57. "Canal Zone Report," 18 December 1925 (Colonel W. P. Chamberlain, chairman), pp. 2-3; quoted in Bonnie and Whitebread, The Marihuana Conviction, p. 134. A second committee was established in 1932, under the chairmanship of Dr. J. F. Siler, Dr. Chamberlain's successor as chief health officer of the Canal Zone, to reinvestigate the question of whether marijuana was in fact a habit-forming drug. In October, the committee reported that based on a sample of thirty-four users, only 15 percent missed the drug when deprived of it while 71 percent expressed a preference for tobacco (J. S. Siler et al., "Marihuana Smoking in Panama," Military Surgeon 73 [1933]: 269-80; quoted in ibid., p. 138).

58. As one historian of the subject has noted, the FBN's reports from the early 1930s "clearly show that it sensed the pressure for a national law, and Commissioner Anslinger personally regarded marihuana use as a vice requiring federal attention. From his first year as head of the FBN, his correspondence advocated eventual national control." (Himmelstein, The Strange Career of Marihuana, p. 56.)

59. Harry J. Anslinger, with Courtney Ryley Cooper, "Marihuana: Assassin of Youth," American Magazine 124 (July 1937): 19, 150.

60. U.S. Congress, Senate, Finance Committee Subcommittee, Hearings on H.R. 6906, 75th Cong., 1st sess., 1937, pp. 11-14; quoted in Bonnie and Whitebread, The Marihuana Conviction, p. 157. At the outset of hearings in the House, the FBN submitted a brief written statement regarding the relationship between marijuana use and psychosis: "Despite the fact that medical men and scientists have disagreed upon the properties of marihuana, and some are inclined to minimize the harmfulness of this drug, the records offer ample evidence that it has a disastrous effect upon many of its users. Recently we have received many reports showing crimes of violence committed by persons while under the influence of marihuana. . . .

"The deleterious, even vicious, qualities of the drug render it highly dangerous to the mind and body upon which it operates to destroy the will, cause one to lose the power of connected thought, producing imaginary delectable situations and gradually weakening the physical powers. Its use frequently leads to insanity." There followed an outline of cases purporting to show the intimate connection between cannabis use and "revolting crimes." (U.S. Congress, House, Committee on Ways and Means, Hearings on H.R. 6385, 75th Cong., 1st sess., 1937, p. 30; quoted in ibid., p. 155.)

61. Public Law No. 238 (75th Congress), 2 August 1937 [50 stat. 551 (1937)].

62. Anslinger's public posture on the relation between marijuana and insanity appears to have remained unchanged, at least into the 1950s, despite the mounting evidence that his position was scientifically totally untenable. Indeed, the FBN was still distributing Anslinger's essay on "Criminal and Psychiatric Aspects of Marihuana" as the leading publication in the field as late as March 1950 (Bonnie and Whitebread, The Marihuana Conviction, p. 194). An extensive treatment of the attitude of the FBN and of Anslinger's personal pronouncements respecting marijuana also appears in Rufus King, The Drug Hang-Up: America's Fifty-Year Folly (New York: Norton, 1972), pp. 69-107.

63. Dr. William C. Woodward of the American Medical Association's Committee on Medical Legislation had not been consulted in the drafting of the bill and took strong exception to its provisions, which he felt unnecessarily inhibited the prerogatives of physicians. Much of his testimony before Congress on the Marihuana Tax Act appears verbatim in Bonnie and Whitebread, The Marihuana Conviction, pp. 164-72.

64. In 1970, $1,969 million was spent on medical research in the United States, of which $1,754 million, or 89 percent, was funded through public expenditures. By 1984, the total expended had risen to $6,798 million, of which $6,426 million, or about 95 percent, were government funds. See Bureau of the Census, Statistical Abstract of the United States, 1986 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1985), p. 97 (Series 147).

65. See Musto, The American Disease, pp. 7-8. Immediately before passage of the Harrison Narcotic Act of 1914 the claim was made that most attacks made by blacks on white women in the South were directly attributable to a "coke-crazed negro brain," and that blacks were made temporarily immune to the "knockdown effects of fatal wounds" made by .32 caliber bullets while under the effects of the drug. As a consequence, a large number of Southern police departments replaced their firearms with .38 caliber revolvers. See Wisotsky, "Exposing the War on Cocaine," pp. 1414-15.

66. See especially the issue-length study of the extent of drug abuse in twenty-five countries that appeared in the journal Addictive Diseases: An International Journal 3 (1977): 1-134. Unfortunately, the enormous difficulty in obtaining reliable figures and the fact that the statistics on drug use are consistently manipulated for political ends make these data at best suggestive.

67. The severity of sentences for heroin possession in certain Third World countries was brought home in dramatic fashion recently when two Australians were hanged at Pudu jail in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, for possession of more than 15 grams of heroin. See Reuter's dispatch, "Two Australians Hanged in Malaysia," Globe and Mail (Toronto), 17 July 1986, p. A8. It is difficult to imagine how the imposition of such sentences could occasion any feeling other than revulsion among civilized people or what the purpose of such barbaric penalties are.

68. This system of narcotics control is dealt with in some detail in Alfred R. Lindesmith, The Addict and the Law (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1965), pp. 164-79.

69. U.S. Congress, House, Committee on Appropriations, Oversight Hearings before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Appropriations, 90th Cong., 2d sess., 1968, Testimony of Henry L. Giordano, Commissioner of Narcotics, Bureau of Narcotics, p. 623; quoted in Kaplan, The Hardest Drug, p. 32.

70. Ibid., pp. 15-38.